Bilateral breast multiple myeloma: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Bilateral breast multiple myeloma: a case report

Cyrus KM Mo, MB, ChB, FRCR1; Alta YT Lai, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1; Sherwin SW Lo, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)2; TS Wong, MB, BS3; Wendy WC Wong1, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1

1 Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Radiology, Gleneagles Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Pathology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Cyrus KM Mo (mkm463@ha.org.hk)

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant disorder

characterised by excessive proliferation of single

clonal plasma cells derived from B cells in the bone

marrow with increased formation of monoclonal

immunoglobulins.1 Multiple myeloma may

involve extramedullary organs or soft tissues

(extramedullary plasmacytoma), commonly in

the upper aerodigestive tract with a predilection

for the head and neck.1 Breast plasmacytoma is

very rare. We present a case of MM with extensive

extramedullary involvement including bilateral

breasts, and mainly focus on the imaging features of

breast plasmacytoma across multi-modalities.

Case report

A 59-year-old female presented for scheduled

ultrasound scan of abdomen for follow-up of

a complicated renal cyst in December 2019.

She had a previous history of diabetes mellitus,

hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and hepatitis B

infection. She was diagnosed with MM 10 years

previously and had previously failed hematopoietic

stem cell transplantation. Ultrasound scan revealed

an enlarged hypoechoic nodule in the liver that

corresponded to the liver lesion detected on earlier

computed tomography (CT) urogram. She also

complained of a palpable nodule in the right lower

quadrant of the abdomen, present for a few months.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast

of liver was arranged to assess the liver lesion and

abdominal wall nodule.

The MRI 1 month later showed significant

enlargement of the liver lesion with heterogeneous

contrast enhancement and restricted diffusion.

No definite contrast washout was demonstrated

in the portovenous phase. The nodule in the right

lower quadrant of the abdominal wall demonstrated

contrast enhancement and restricted diffusion as

well. Features of both lesions were suggestive of

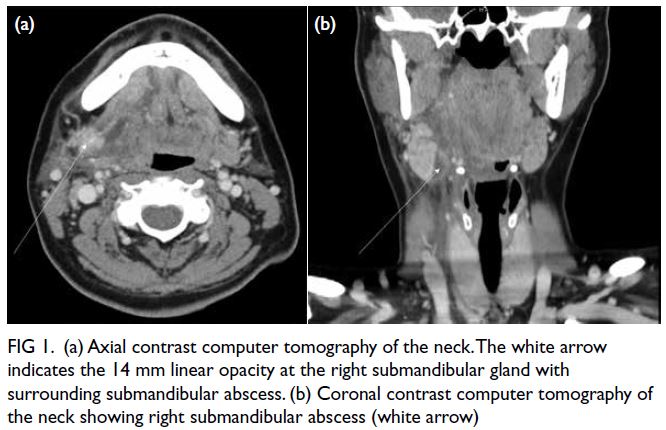

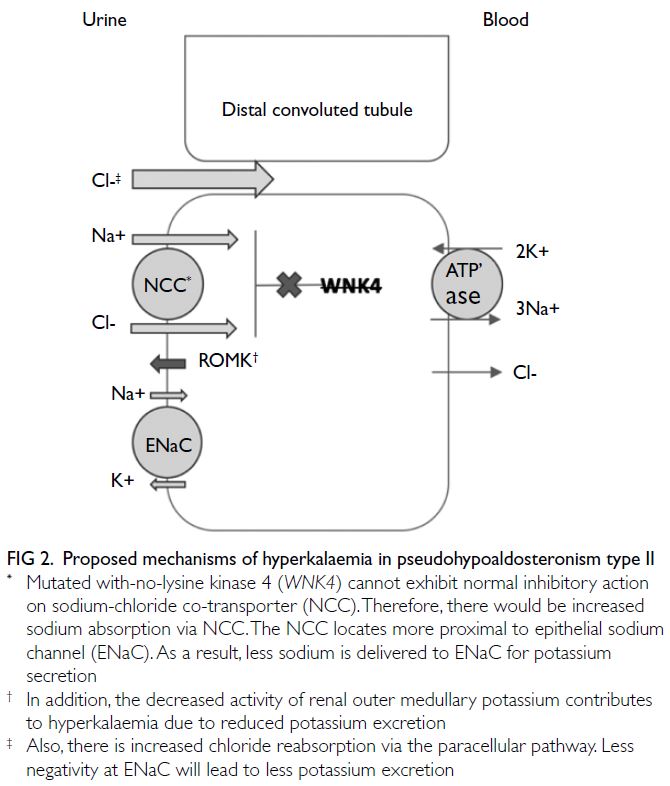

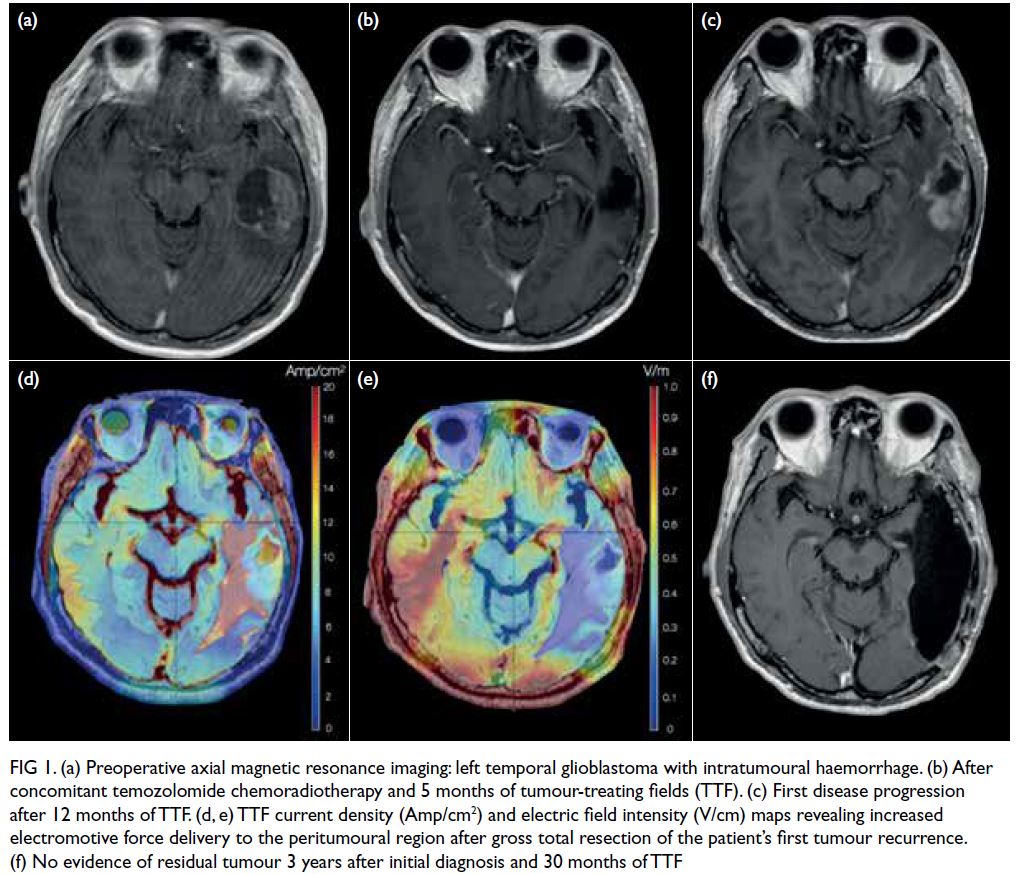

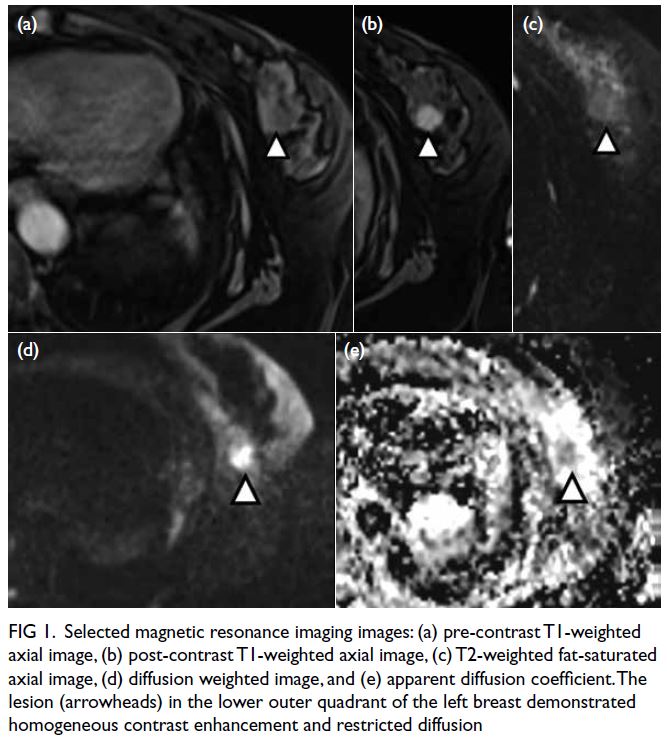

malignancy. The MRI also revealed a 1.3 cm T1

isointense T2 hyperintense contrast enhancing

nodule with restricted diffusion in the outer lower

quadrant of the left breast (Fig 1).

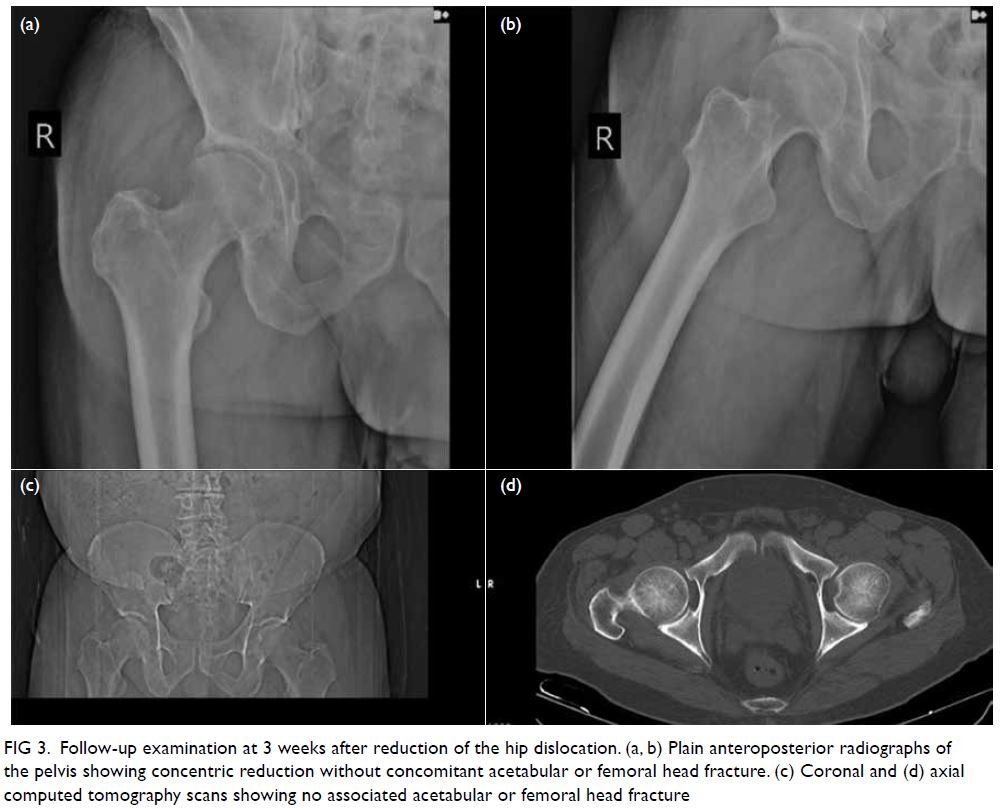

Figure 1. Selected magnetic resonance imaging images: (a) pre-contrast T1-weighted axial image, (b) post-contrast T1-weighted axial image, (c) T2-weighted fat-saturated axial image, (d) diffusion weighted image, and (e) apparent diffusion coefficient. The lesion (arrowheads) in the lower outer quadrant of the left breast demonstrated homogeneous contrast enhancement and restricted diffusion

Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of

the right lower quadrant abdominal wall nodule

was performed in February 2020. The pathological

diagnosis was plasmacytoma.

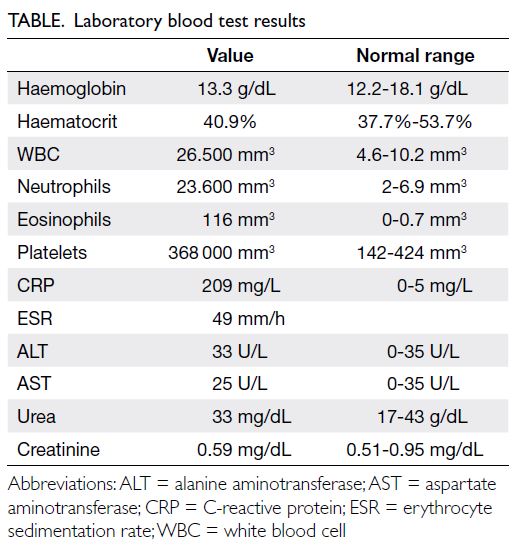

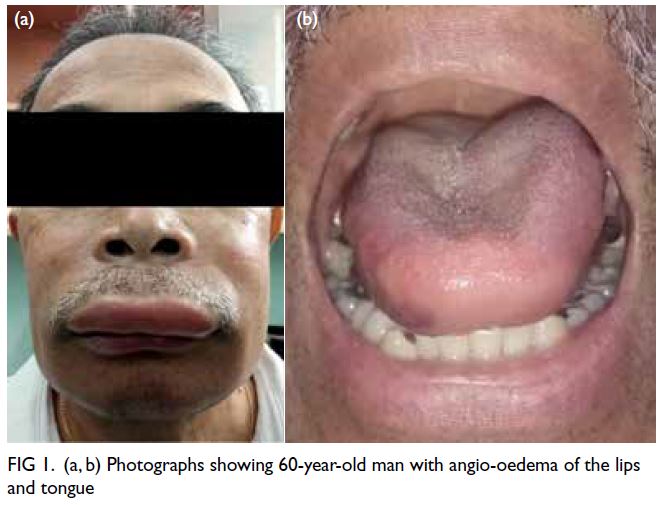

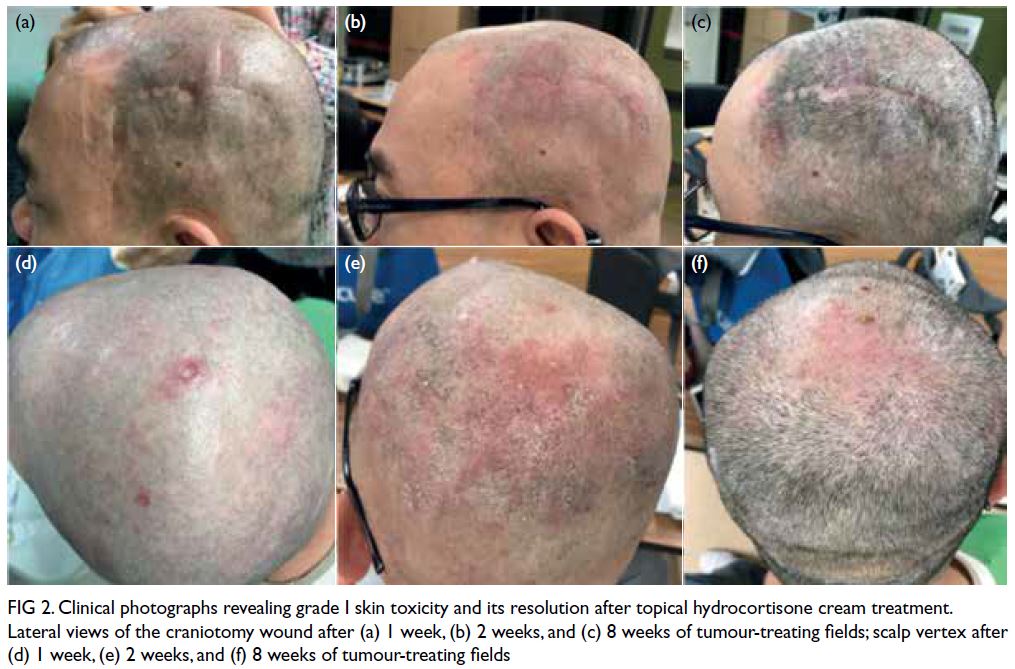

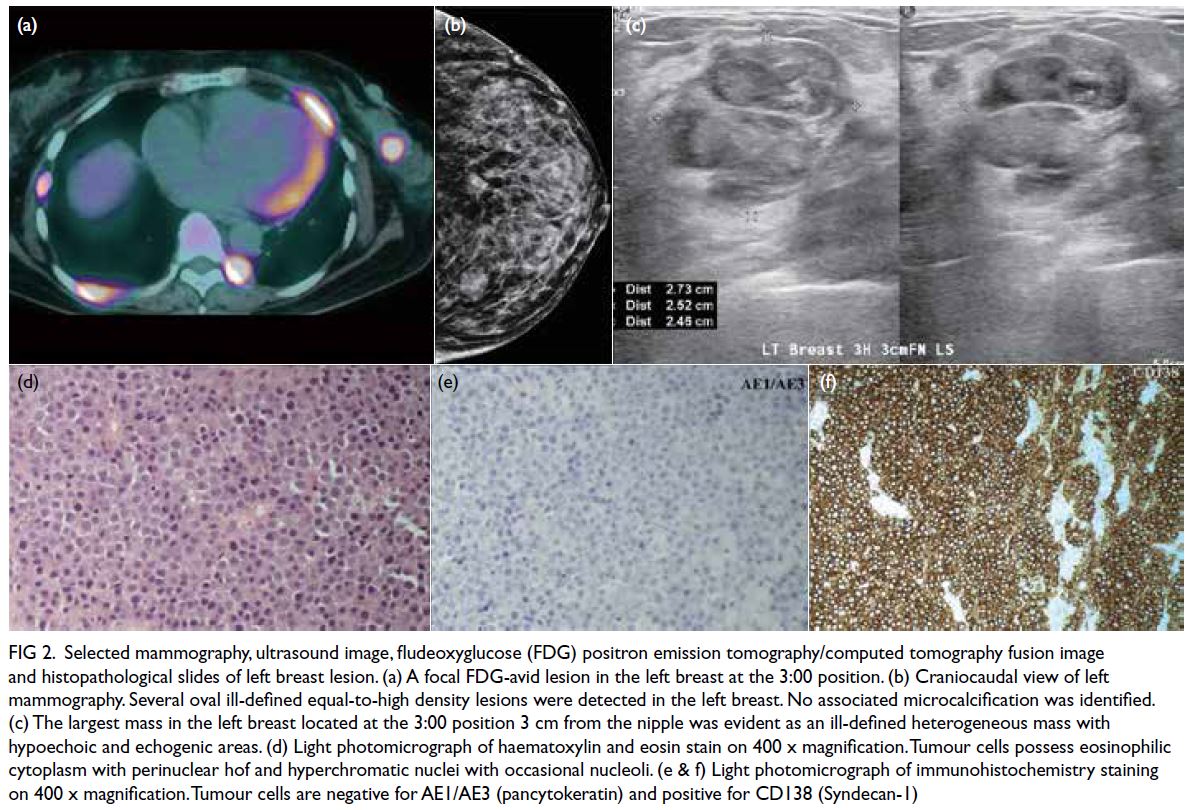

Dual-tracer positron emission tomography

(PET)/CT was performed in early March 2020 at

a private institution to assess disease involvement.

There were multiple acetate (Ac) and fludeoxyglucose

(FDG)-avid soft tissue nodules in bilateral breasts,

measuring up to 1.5 × 1.4 cm with FDG maximum

standard unit value (SUVmax) 8.4 and Ac SUVmax

5.0 in left breast (Fig 2a) and 1.4 × 1.0 cm with FDG

SUVmax 7.0 and Ac SUVmax 6.6 in right breast.

There were a few left axillary level I lymph nodes

measuring up to 0.9 × 0.8 cm with FDG SUVmax 3.3

and Ac SUVmax 3.9.

Figure 2. Selected mammography, ultrasound image, fludeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography fusion image and histopathological slides of left breast lesion. (a) A focal FDG-avid lesion in the left breast at the 3:00 position. (b) Craniocaudal view of left mammography. Several oval ill-defined equal-to-high density lesions were detected in the left breast. No associated microcalcification was identified. (c) The largest mass in the left breast located at the 3:00 position 3 cm from the nipple was evident as an ill-defined heterogeneous mass with hypoechoic and echogenic areas. (d) Light photomicrograph of haematoxylin and eosin stain on 400 x magnification. Tumour cells possess eosinophilic cytoplasm with perinuclear hof and hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional nucleoli. (e & f) Light photomicrograph of immunohistochemistry staining on 400 x magnification. Tumour cells are negative for AE1/AE3 (pancytokeratin) and positive for CD138 (Syndecan-1)

Bilateral mammography and breast ultrasound

were arranged in early April 2020 to assess bilateral

breast lesions. There were multiple oval and ill-defined

equal-to-high density lesions in both

breasts. The largest lesion located at the upper

outer quadrant of the right breast measured 3.6 × 2.8 cm and was palpable. No associated suspicious

microcalcifications were detected. There was no

architectural distortion, skin thickening or enlarged

lymph nodes on mammography (Fig 2b).

Subsequent breast ultrasound on the same

section revealed scattered oedematous areas in both

breasts. A heterogeneous mass with hypoechoic and

echogenic areas was detected in the left breast at a

3:00 position, 3 cm from the nipple (Fig 2c). Posterior

enhancement was evident. This mass corresponded

to the lesion detected on previous MRI. The size was

2.7 × 2.5 × 2.5 cm. There was interval enlargement

compared with previous MRI (which was 1.3 cm).

Multiple hypoechoic, echogenic, and heterogeneous

masses and nodules were identified in other areas

of both breasts. The largest one in the right breast

located at a 9:00 position 5 cm from the nipple

measured 4.5 × 2.6 × 4.1 cm. There was an irregular hypoechoic enlarged left axillary lymph node with

loss of fatty hilum. Ultrasound-guided fine needle

aspiration of this node and core biopsies of the

dominant masses in each breast were performed

in the same section. The pathological diagnoses of

the breast masses and left axillary lymph node were

consistent with plasmacytoma (Fig 2d-f). Two weeks

later (mid-April 2020), the patient was admitted

with multilobar pneumonia and severe metabolic

acidosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Unfortunately, she passed away 4 days later.

Discussion

Breast plasmacytoma is extremely rare.

Approximately 50 cases have been reported in the

literature since 1925.2 3 4 5 The prevalence is unknown.

Surov et al6 reported a prevalence of 1.5% for breast

plasmacytoma among patients with plasmacytoma

in their institution. Involvement of the breast was a

secondary event of MM in 85% and more than half of

the lesions were unilateral.6

There are some differences in the

ultrasonographic features of breast MM between

this case and those reported in the literature. For the cases described by Ali et al2 and Park5, breast MM

was revealed as a well-defined oval hypoechoic mass

on ultrasound. In our patient, it was an indistinct

oval heterogeneous mass with hypoechoic and

echogenic areas.

Compared with typical primary breast cancer

(invasive ductal carcinoma) that is usually revealed

as an irregular spiculated high-density mass on

mammogram and an anti-parallel hypoechoic

irregular spiculated mass on ultrasound, there are

no characteristic imaging features of breast MM. On

mammography, it can present as a single or multiple

high-density round or oval lesion(s) that is/are

circumscribed or ill-defined.2 It can show as diffuse

infiltration. Association with microcalcifications

is rarely reported. On ultrasound, the features are

well-defined echo-poor, hypoechoic, or hyperechoic

solid masses with hypervascularity.2 Mixed hypo- to

hyper-echoic masses with indistinct margins are also

possible. Posterior acoustic features are variable.

Posterior acoustic enhancement can be evident but

absence of acoustic transmission or even posterior

acoustic shadowing has been reported in some

cases.

There are limited case reports of MRI and PET/

CT features of breast MM. On MRI, it shows as a T1-weighted intermediate to hypointense T2-weighted

hyperintense lesion with homogeneous or rim

enhancement. Restricted diffusion and early rapid

contrast enhancement with washout kinetics are the

reported features.5 It appears as a homogeneous soft

tissue lesion with high FDG uptake on PET/CT.

No case report has discussed the features of

breast MM on dual-tracer PET/CT. It was revealed

as an Ac-avid lesion in our patient, indicative of high

metabolism of malignant plasma cells. There are

provisos in this case report. The MRI protocols did

not relate specifically to breast imaging and contrast

kinetics was not performed.

Conclusion

There are no specific radiological features of breast MM. In bilateral multiple breast masses, the

differential diagnoses are lymphoma, metastasis,

synchronous primary breast cancer, secondary

involvement of haematological disorder or benign conditions such as fibroadenoma. Biopsy for

histopathological diagnosis is advised.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CKM Mo, AYT Lai.

Acquisition of data: SSW Lo, TS Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SSW Lo, TS Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: CKM Mo, AYT Lai, WWC Wong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CKM Mo, AYT Lai, WWC Wong.

Acquisition of data: SSW Lo, TS Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SSW Lo, TS Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: CKM Mo, AYT Lai, WWC Wong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CKM Mo, AYT Lai, WWC Wong.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent for publication was unobtainable

from the deceased patient's next-of-kin despite all reasonable

efforts.

References

1. Angtuaco EJ, Fassas AB, Walker R, Sethi R, Barlogie B. Multiple myeloma: clinical review and diagnostic imaging.

Radiology 2004;231:11-23. Crossref

2. Ali HO, Nasir Z, Marzouk AM. Multiple myeloma breast involvement: a case report. Case Rep Radiol

2019;2019:2079439. Crossref

3. Kaviani A, Djamali-Zavareie M, Noparast M, Keyhani-Rofagha S. Recurrence of primary extramedullary

plasmacytoma in breast both simulating primary breast

carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2004;2:29. Crossref

4. Lee HS, Kim JY, Kang CS, Kim SH, Kang JH. Imaging

features of bilateral breast plasmacytoma as unusual initial

presentation of multiple myeloma: case report and literature

review. Acta Radiol Short Rep 2014;3:2047981614557666. Crossref

5. Park YM. Imaging findings of plasmacytoma of both breasts as a preceding manifestation of multiple myeloma.

Case Rep Med 2016;2016:6595610. Crossref

6. Surov A, Holzhausen HJ, Ruschke K, Arnold D, Spielmann RP. Breast plasmacytoma. Acta Radiol

2010;51:498-504. Crossref