Rethink personalised sudden cardiac death risk assessment in non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2025 Jun;31(3):236–9 | Epub 14 Apr 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Rethink personalised sudden cardiac death risk assessment in non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy: a case report

Kevin WC Lun, MB, BS, MRCP1 #; Jonan CY Lee, MB, ChB, FRCR2; Eric CY Wong, MB, BS, FHKCP1; Michael KY Lee, MB, BS, FHKCP1; Derek PH Lee, MB, ChB, FHKCP1 #

1 Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

# Equal contribution

Corresponding author: Dr Kevin WC Lun (lkw708@ha.org.hk)

Case presentation

A 56-year-old man was presented to the emergency

department of our institution in June 2023 and has

had been followed up in our medical clinic for 1 year

prior to his current hospital admission. He had been

diagnosed with frequent symptomatic premature

ventricular complexes with an ectopic burden of

8.2% on extended ambulatory rhythm monitoring.

There were also multiple recorded episodes of non-sustained

ventricular tachycardia. Beta-blocker

was initiated and uptitrated according to clinical

symptoms. His family history was remarkable for

the sudden cardiac death of his father at the age of

64 years. Subsequent transthoracic echocardiogram

of the patient revealed a global hypokinetic left

ventricle with a biplane-measured left ventricular

ejection fraction (LVEF) of 45%. There was mild

left atrial enlargement with a two-dimensional area

of 25.7 cm2 but no other structural abnormalities.

Computed tomography coronary angiogram showed

mild to moderate coronary artery disease in three

vessels and guideline-directed medical treatment

was initiated. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

(CMR) was scheduled to assess cardiac structures

and function, as well as tissue characterisation for

features of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. He

had been scheduled to undergo catheter ablation

for frequent symptomatic premature ventricular

complexes.

The patient presented to our emergency

department with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. He

had been found collapsed adjacent to a swimming

pool and a bystander had initiated cardiopulmonary

resuscitation. Spontaneous circulation was restored

shortly after a single defibrillation delivered by

an automated external defibrillator and he was

transferred to our hospital immediately. On arrival at

the emergency department, he was hemodynamically

stable with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15.

High-sensitive troponin I level was elevated

at 44.9 ng/L. Electrocardiogram showed sinus

rhythm of 71 beats/min with occasional premature ventricular complexes. There was no ST-segment

elevation or significant conduction abnormalities.

Bedside echocardiogram showed a similar biplane-measured

LVEF of 43% with global hypokinesia.

Urgent coronary angiogram showed non-occlusive

moderate to severe coronary artery disease in three

vessels. Given his current presentation, together

with angiographic progression in coronary artery

disease, complete revascularisation was performed

uneventfully. He was then transferred to our cardiac

care unit postoperatively for close monitoring.

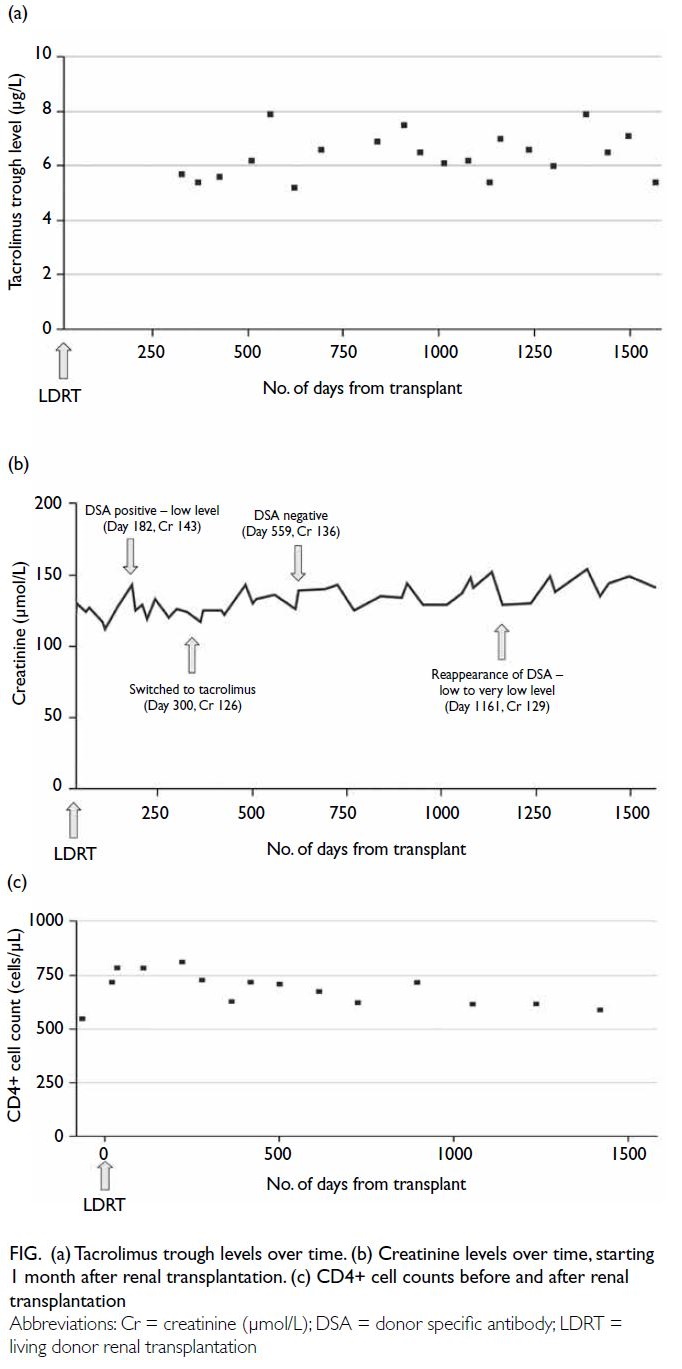

Inpatient CMR revealed a non-dilated left ventricle

with mildly reduced LVEF of 43% with global

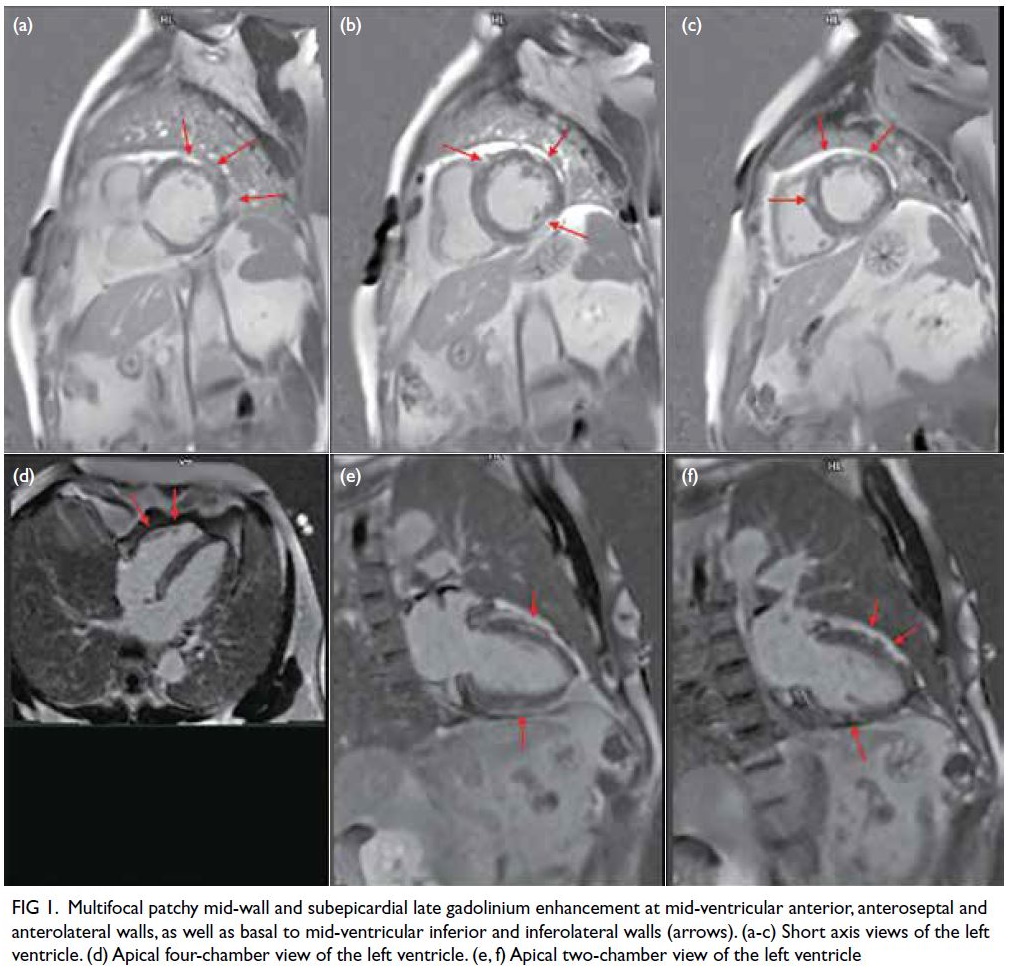

hypokinesia. There was multifocal patchy mid-wall

and subepicardial late gadolinium enhancement

(LGE) at the mid-ventricular anterior, anteroseptal

and anterolateral walls, as well as basal to mid-ventricular

inferior and inferolateral walls (Fig 1). There was no evidence of myocardial infarct.

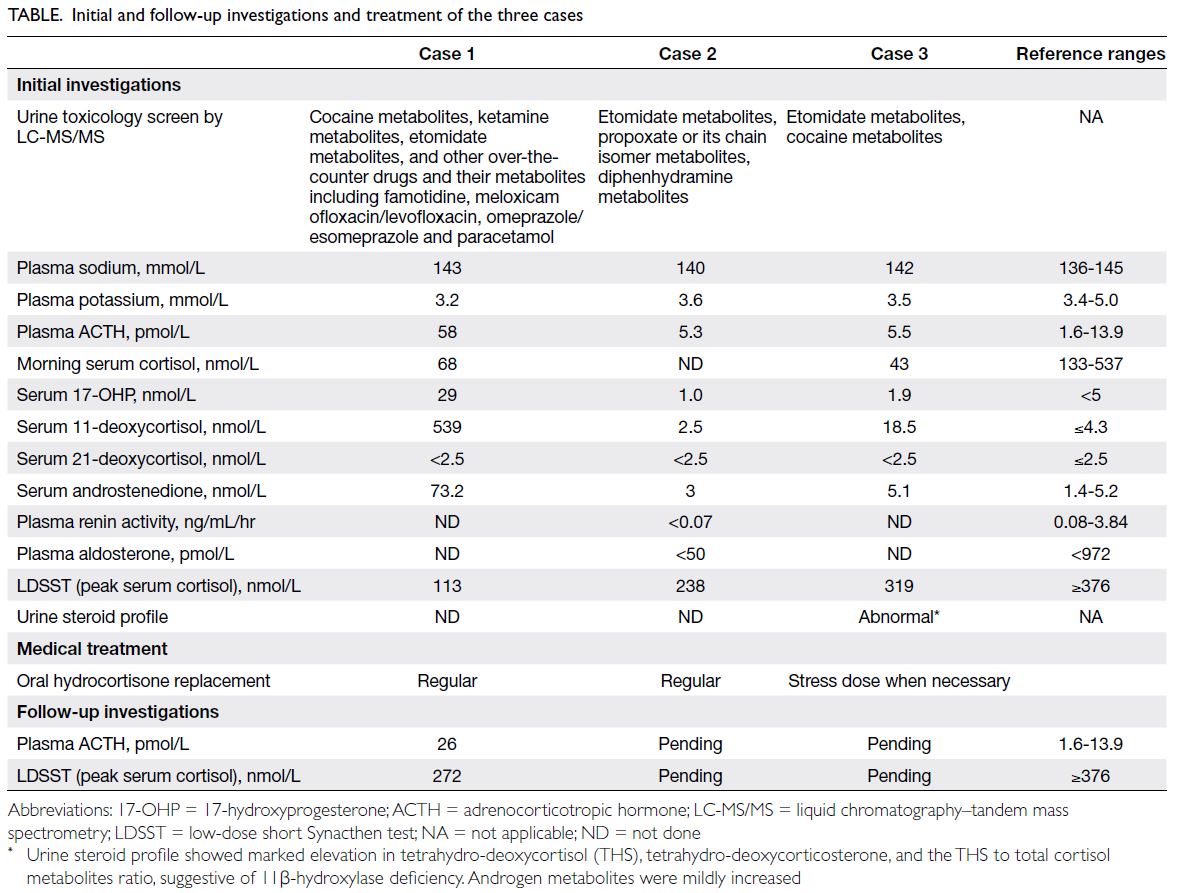

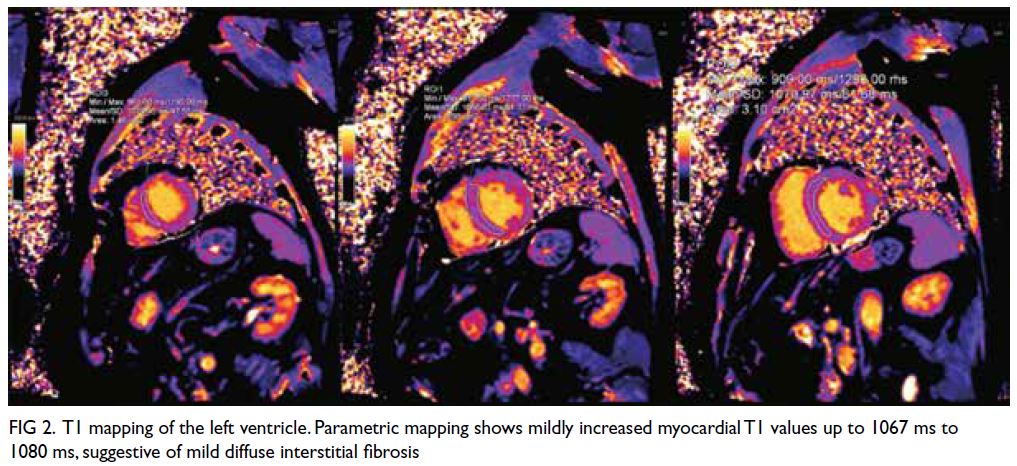

Parametric mapping showed a mild increase in

myocardial T1 with values up to 1067 ms to 1080

ms (native T1 values in healthy subjects obtained in

our Aera 1.5T magnetic resonance imaging scanner

[Siemens, Munich, Germany] is 996±26 ms for

males), suggestive of mild diffuse interstitial fibrosis

(Fig 2). Prior to hospital discharge, a transvenous

implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) was

implanted for secondary prevention. Subsequent

genetic testing identified a heterozygous pathogenic

truncating variant NM_001458.5(FLNC):c.3279del

p.(Gly1094Alafs*4) in the filamin-C gene. The

final clinical diagnosis was sudden cardiac arrest

secondary to filamin-C variant–associated

cardiomyopathy in a patient with non-dilated left

ventricular cardiomyopathy (NDLVC) and mid-range

ejection fraction.

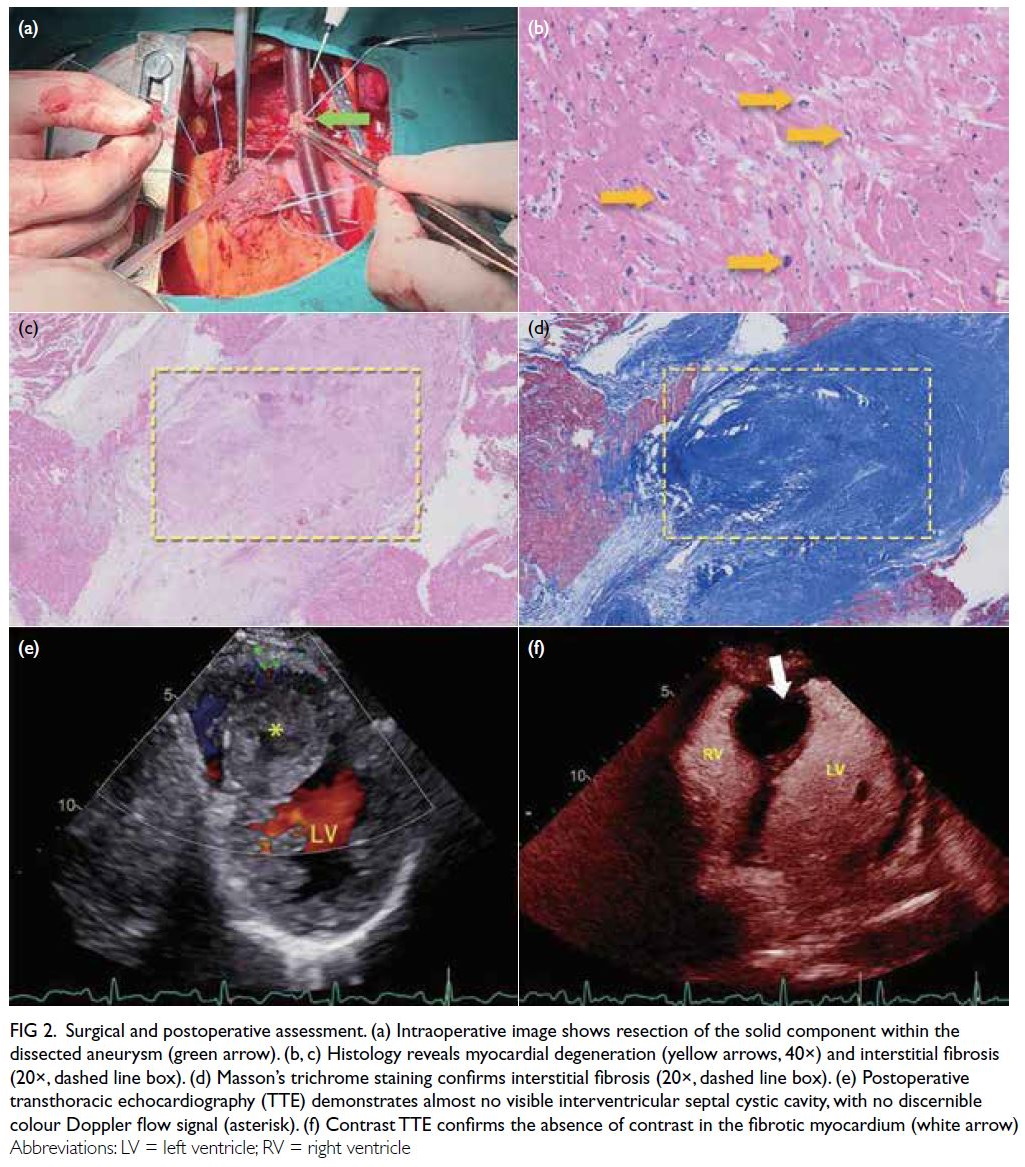

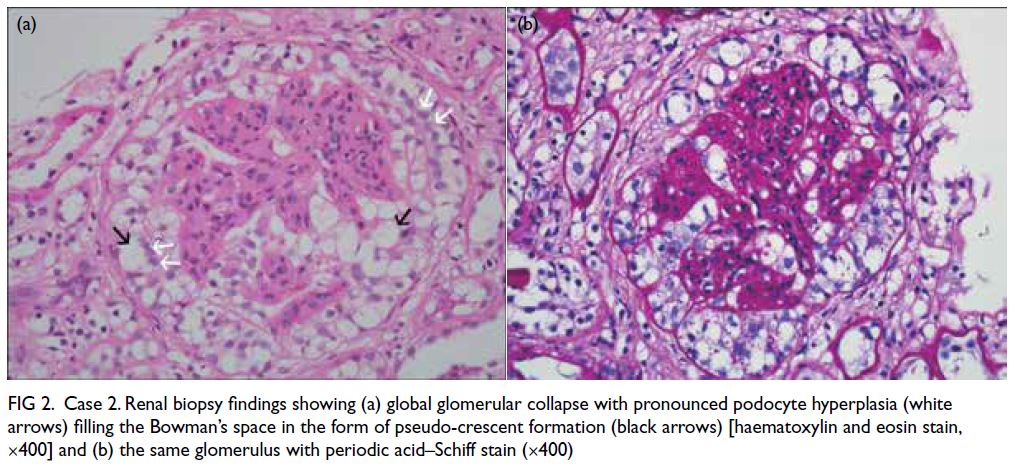

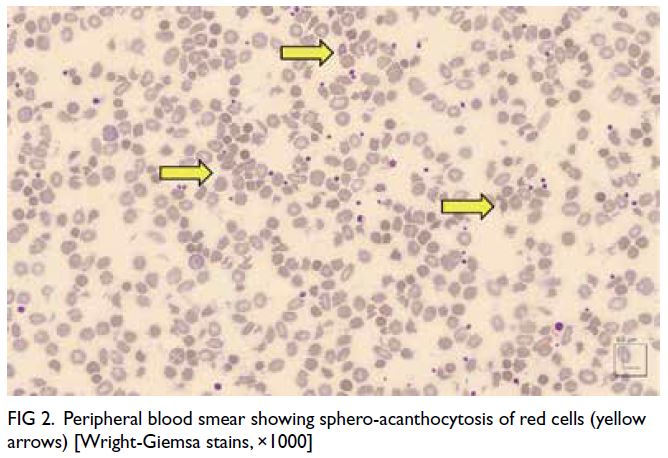

Figure 1. Multifocal patchy mid-wall and subepicardial late gadolinium enhancement at mid-ventricular anterior, anteroseptal and anterolateral walls, as well as basal to mid-ventricular inferior and inferolateral walls (arrows). (a-c) Short axis views of the left ventricle. (d) Apical four-chamber view of the left ventricle. (e, f) Apical two-chamber view of the left ventricle

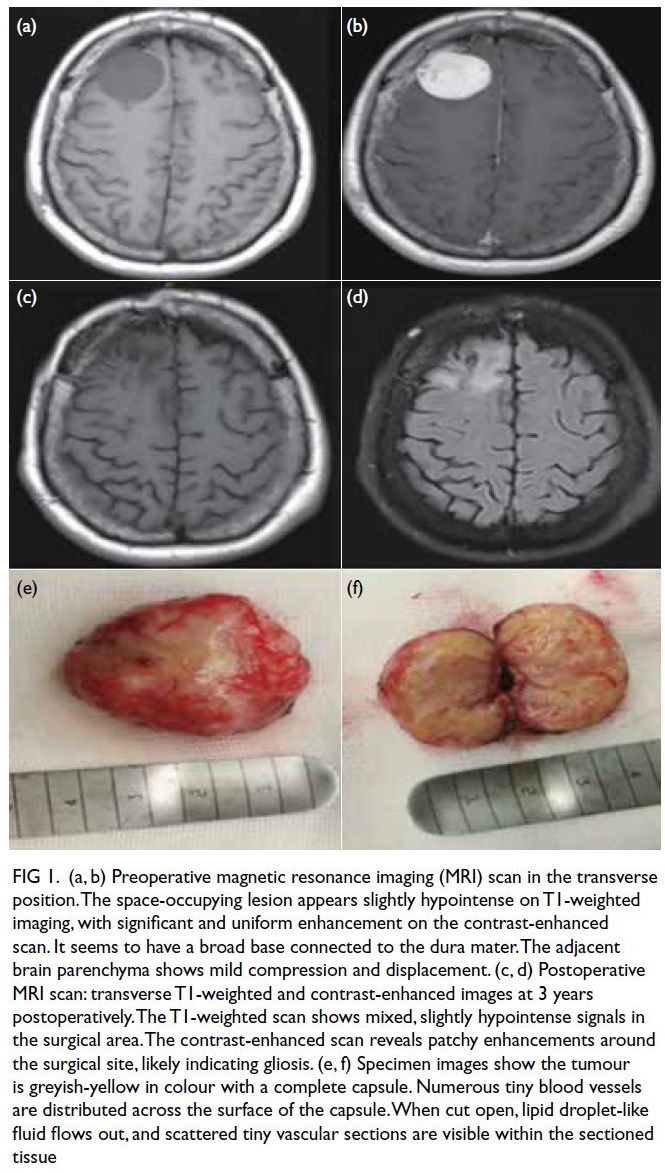

Figure 2. T1 mapping of the left ventricle. Parametric mapping shows mildly increased myocardial T1 values up to 1067 ms to 1080 ms, suggestive of mild diffuse interstitial fibrosis

Discussion

The filamin-C gene encodes the filamin-C protein

that plays essential roles in the sarcomere stability

in cardiac muscles. Filamin-C variants have been

increasingly recognised as an important cause of cardiomyopathy. It has been identified in

approximately 3% to 4% of patients with dilated

cardiomyopathy and commonly presents in early-to-mid

adulthood with high arrhythmic risks.1

According to the 2021 European Society of

Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the diagnosis

and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure,2

primary prevention ICD is indicated in patients

with symptomatic heart failure with an LVEF of lower than 35%

despite optimal medical treatment and a reasonable

quality of life. Such recommendation is supported

by numerous landmark trials including MADIT

(Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation

Trial),3 DEFINITE (DEFibrillators In Non-Ischemic

Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation),4 and SCD-HeFT

(the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure

Trial).5 In addition, several additional clinical

risk factors should also be considered in sudden

cardiac death risk assessment, especially in patients

with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy.2 These risk

factors include significant LGE on CMR, younger

age, and specific genotypes. Nonetheless these

recommendations are ambiguous, and the guideline

has not defined, for example, the burden of LGE

and variant mechanisms in several high-risk genes

that would warrant ICD implantation. Moreover,

there are limited recommendations for primary

prevention ICD in patients with heart failure with

mid-range or preserved ejection fraction.

In the updated 2023 ESC Guidelines for

the management of cardiomyopathies,6 a new

entity of NDLVC is introduced. An algorithm for

consideration of primary prevention ICD similar

to that for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy is

recommended in this patient population. Patient

genotype and imaging features on CMR have been

proposed in the early sudden cardiac death risk

assessment for patients with NDLVC. A previous

study has demonstrated a higher rate of malignant

arrhythmic events in patients who are genotype-positive,

compared with their genotype-negative

counterparts.7 Such association has been observed

irrespective of LVEF. Variants in certain genes

including lamin A/C, phospholamban, filamin-C,

RNA-binding motif protein 20, desmoplakin and

plakophilin-2 are associated with a high risk of

malignant ventricular arrhythmias and sudden

cardiac death. Apart from genotype information,

the presence and distribution of LGE on CMR,

such as a ring-like pattern of LGE, has also been

shown to be a strong risk marker for ventricular

arrhythmias.8 Hence, based on the current ESC

Guidelines,6 primary prevention ICD should be

considered in patients with NDLVC and high-risk

genotype and in the presence of additional

risk factors such as syncope and LGE on CMR,

irrespective of LVEF.

Our case highlights the need to incorporate a patient’s genotype and imaging features on CMR into

the personalised risk assessment for sudden cardiac

death in patients with NDLVC. This will facilitate

a more comprehensive and informative discussion

about the indication for primary prevention ICD

and improve the clinical outcome for patients with

cardiomyopathy.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KWC Lun, DPH Lee.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KWC Lun, DPH Lee.

Drafting of the manuscript: KWC Lun, DPH Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KWC Lun, DPH Lee.

Drafting of the manuscript: KWC Lun, DPH Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency

in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. The patient provided consent for all treatments and

procedures, and consent for publication of the case report.

References

1. Agarwal R, Paulo JA, Toepfer CN, et al. Filamin C

cardiomyopathy variants cause protein and lysosome

accumulation. Circ Res 2021;129:751-66. Crossref

2. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and

chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599-726. Crossref

3. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic

implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial

infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med

2002;346:877-83. Crossref

4. Kadish A, Dyer A, Daubert JP, et al. Prophylactic

defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic

dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2151-8. Crossref

5. Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart

failure. N Engl J Med 2005;352:225-37. Crossref

6. Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, et al. 2023 ESC

Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur

Heart J 2023;44:3503-626. Crossref

7. Escobar-Lopez L, Ochoa JP, Mirelis JG, et al. Association

of genetic variants with outcomes in patients with

nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol

2021;78:1682-99. Crossref

8. Meier C, Eisenblätter M, Gielen S. Myocardial late

gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in cardiac magnetic

resonance imaging (CMR)—an important risk marker for

cardiac disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2024;11:40. Crossref