Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):178–80 | Epub 8 Apr 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Pain management for painful brachial neuritis

after COVID-19: a case report

Vivian YT Cheung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology); Fiona PY Tsui, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology); Joyce MK Cheng, BHlthSc, FHKAN (Perioperative)

Department of Anaesthesia, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Vivian YT Cheung (cyt086@ha.org.hk)

Case report

In October 2020, a 55-year-old Chinese man

travelled from Hong Kong to Paris to attend a family

funeral. He had psoriatic arthropathy in remission

without chronic pain. In November 2020 while still

in France, he and seven family members developed

fever and upper respiratory symptoms, confirmed to

be coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The family

remained in home isolation and required no medical

treatment. The patient self-treated with traditional

Chinese medication: Lianhua Qingwen herbal

capsules for 1 week. Two weeks later, he returned

to Hong Kong after testing negative for COVID-19.

In December 2020, during mandatory quarantine

on re-entry to Hong Kong, the patient suddenly

developed pain that extended from the neck and

right interscapular region to the shoulder and down

along the ulnar side of the right arm and forearm. The

patient described the pain as shooting and drilling in

nature, constantly severe, worst at the interscapular

region, and aggravated by shoulder movement.

He also reported disturbed sleep and numbness

over his entire right arm and weakened right hand

grip. He had no other joint pain, rash, vesicles, or

fever. At this time, he was still resting alone in a

quarantine hotel and performing no physical work.

Most activities of daily living were manageable but

some, such as bathing and dressing, were difficult.

Diclofenac 100 mg daily and gabapentin 200 mg

3 times daily prescribed at a COVID-19 Clinic were

ineffective. The patient’s younger sister who had

recovered in France without medication reported

similar symptoms in her left arm.

The patient presented to our pain clinic

1 month after pain onset. His motor symptoms had

spontaneously improved although disturbing right

shoulder and interscapular pain with paraesthesia

persisted. There were no muscle wasting, scar, rash,

or trophic changes. The patient’s right arm was

slightly warmer than the left, and upper limb joints

were not swollen or tender and there was full range

of movement. He reported decreased sensation to

light touch, cold and pinprick over the whole right

arm, but his sense of vibration and proprioception

were preserved. No touch or mechanical allodynia or hyperalgesia were noted. Apart from slightly

weakened thumb opposition, other muscle strength,

tendon reflexes and neck examination were

unremarkable.

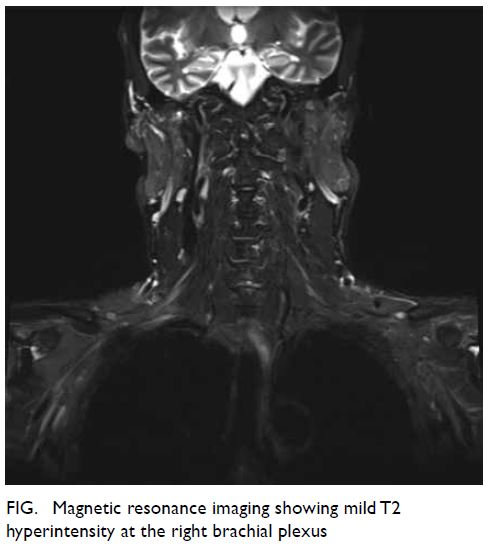

Analgesia was changed to pregabalin 75 mg

twice per day and etoricoxib 90 mg daily as needed,

and the patient was referred for occupational

therapy for grip strengthening. Magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) in March 2021 revealed mild T2

hyperintensity at the right brachial plexus, suggestive

of resolving neuritis (Fig). There was also cervical

spondylosis without significant intervertebral

foraminal narrowing or cord compression. Nerve

conduction study in March 2021 was normal.

Electromyography was not performed due to good

neurological recovery.

At a subsequent 3-month follow-up

examination in March 2021, the patient reported

continued improvement with little or no pain. He

reported only intermittent paraesthesia and mild

weakness of his right hand and fingers. As a right-hander,

he continued to have trouble turning keys and

using chopsticks and pens. He coped with his office work with a speech-to-text converter to minimise

keyboard usage. He could manage most household

chores, including shopping for groceries, and slept

well. He was calm and grieving appropriately for the

loss of his mother. Pregabalin was gradually reduced,

and he was weaned off etoricoxib.

Discussion

The Coronavirus family is known for its neurotropism

with 36% of COVID-19 infected patients reporting

some form of neurological manifestation.1

Mechanisms involve direct neural infection,

and indirect inflammatory and immunological

reactions. Other possibilities are targeting of

neuronal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2,

vasculitis, thrombosis and iatrogenic, such as prone

position-related effects or neuropathies.2

The pathophysiology of acute brachial neuritis is not well understood but the pre-existence of viral

infection supports immunological mechanisms.

Affected subjects have more lymphocytic activity

to brachial (versus sacral) plexus nerve extracts and

increased antibodies to peripheral nerve myelin. A

hereditary form with mutation-related deficiency in

proteins from the septin family has been identified.2

Our patient took Lianhua Qingwen, a traditional

Chinese medicine prepared from 13 herbs, shown to

bind to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and shorten

the course of COVID-19 infection.3 Drug-induced

plexopathy, although less likely, remains possible.

Acute brachial neuritis is self-limiting but

classically presents with excruciating pain at the

shoulder, neck and interscapular region, followed by

shoulder girdle weakness. Diagnosis is clinical and

investigations are supportive. Cervical pathology is

the major differential diagnosis but was excluded in

our patient by MRI that revealed cervical spondylosis

without nerve or cord compression or signal changes.

Given the rheumatological history in our case, active

autoimmune disease was also possible, but he had no

such features.

To the best of our knowledge three cases of

post-COVID-19 brachial neuritis4 5 6 have been

reported but none in Hong Kong. Brachial neuritis

is rare with an incidence of only 1.64 cases per

100 000 person-years, and underreporting is

expected with isolation and restricted healthcare

access during COVID-19. Compared to existing

three cases, two cases similarly involved middle-aged

men with delayed neuropathic symptoms

2 weeks after COVID-19 confirmation. One had

similar symptoms to our patient, whereas the other

two had either purely sensory components or solely

proximal median nerve involvement. Our case

and one existing case demonstrated classical MRI

changes. Nerve conduction study in our patient did

not demonstrate reduced action potential amplitude

in affected nerves, which may have been related to its performance at a later course of the disease.

Given the rarity of the entity and its occurrence

in our patient and his sister, further research to

investigate the role of genetic susceptibility to the

acute form is warranted. Management of brachial

neuritis is supportive and focused on pain control

and functional rehabilitation with physiotherapy and

occupational therapy. There is limited evidence that

steroids and immunoglobulins will hasten recovery

so their use should be balanced against the risk of

viral replication. Currently, there are no established

guidelines for pain management in patients with

or recently recovered from COVID-19. Specific

precautions should be taken in pain management of

these cases.

Paracetamol has limited efficacy for neuropathic

pain. Care should be taken for patients with severe

COVID-19, because viral-induced cytokine storm

can suppress cytochrome P450, increasing the risks

of hepatotoxicity. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs offer effective analgesia for brachial neuritis

by suppressing cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin

production. Although there were early concerns

about ibuprofen-associated decompensation

in patients with COVID-19, this has not been

supported by the World Health Organization after

data review. Meanwhile, cyclooxygenase-2 selective

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs disturb the

thromboxane A2–prostacyclin balance, potentially

enhancing thrombotic tendency in patients with

COVID-19. Our case illustrates the safe use of

cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in a patient recently

recovered from COVID-19. Among antineuropathic

agents, gabapentinoids have relatively few adverse

effects, lower cardiac toxicity, and fewer drug-drug

interactions than tricyclic antidepressants and

serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors. Our

patient was initially prescribed a relatively low dose

of gabapentin that may account for its lack of effect.

He was changed to pregabalin at a higher equivalent

dose, with a better pharmacological profile with

linear dose-response relationship and faster onset.

Physicians should be alert to the sedative effects

of analgesia that may worsen COVID-19-related

ventilatory impairment. Opioids should be reserved

for severe refractory pain.

Pain management for patients with or

recently recovered from COVID-19 can be socially

challenging. The need for quarantine delays

presentation and management, and the associated

mental stress and lack of social support may

perpetuate pain. Although telemedicine enables

remote medical care, controversies remain, and

psychological engagement is less effective. Our

patient’s appropriate grief reaction and illness coping

mechanism minimises risk of chronic pain.

Our case report is the first to focus on the

clinical management of brachial neuritis in patients with or recently recovered from COVID-19, and the

first to identify a possible case series within a family.

We hope our report of COVID-19-related brachial

neuritis can promote awareness and understanding.

Future research should focus on its pathophysiology

including genetic susceptibility. Whether COVID-19 vaccination alters the course of acute brachial

neuritis warrants further observation.

Author contributions

Concept or design: VYT Cheung, FPY Tsui.

Acquisition of data: VYT Cheung, JMK Cheng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: VYT Cheung.

Drafting of the manuscript: VYT Cheung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: FPY Tsui, JMK Cheng.

Acquisition of data: VYT Cheung, JMK Cheng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: VYT Cheung.

Drafting of the manuscript: VYT Cheung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: FPY Tsui, JMK Cheng.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Annie Chu for contributing to the

clinical management, and Drs Mandy Au Yeung and Kendrick

Tang for the investigations.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for the

treatment/procedures, and for publication.

References

1. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations

of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in

Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:683-90. Crossref

2. Fernandez CE, Franz CK, Ko JH, et al. Imaging review

of peripheral nerve injuries in patients with COVID-19.

Radiology 2021;298:E117-30. Crossref

3. Alam S, Sarker MM, Afrin S, et al. Traditional herbal

medicines, bioactive metabolites, and plant products

against COVID-19: update on clinical trials and mechanism

of actions. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:671498. Crossref

4. Mitry MA, Collins LK, Kazam JJ, Kaicker S, Kovanlikaya A.

Parsonage-turner syndrome associated with SARS-CoV2

(COVID-19) infection. Clin Imaging 2021;72:8-10. Crossref

5. Siepmann T, Kitzler HH, Lueck C, Platzek I, Reichmann H,

Barlinn K. Neuralgic amyotrophy following infection with

SARS-CoV-2. Muscle Nerve 2020;62:E68-70. Crossref

6. Cacciavillani M, Salvalaggio A, Briani C. Pure sensory

neuralgic amyotrophy in COVID-19 infection. Muscle

Nerve 2021;63:E7-E8. Crossref