SARS-CoV-2–associated myopathy with positive anti–Mi-2 antibodies: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2023 Apr;29(2):170–2 | Epub 17 Mar 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

SARS-CoV-2–associated myopathy with positive anti–Mi-2 antibodies: a case report

Aleksandra Plavsic, MD1,2; Snezana Arandjelovic, MD, PhD1,2; Aleksandra Peric Popadic, MD, PhD1,2; Jasna Bolpacic, MD, PhD1,2; Sanvila Raskovic, MD, PhD1,2; Rada Miskovic, MD1,2

1 Clinic of Allergy and Immunology, University Clinical Centre of Serbia, Beograd, Serbia

2 Medical Faculty, University of Belgrade, Beograd, Serbia

Corresponding author: Dr Rada Miskovic (rada_delic@hotmail.com)

Case report

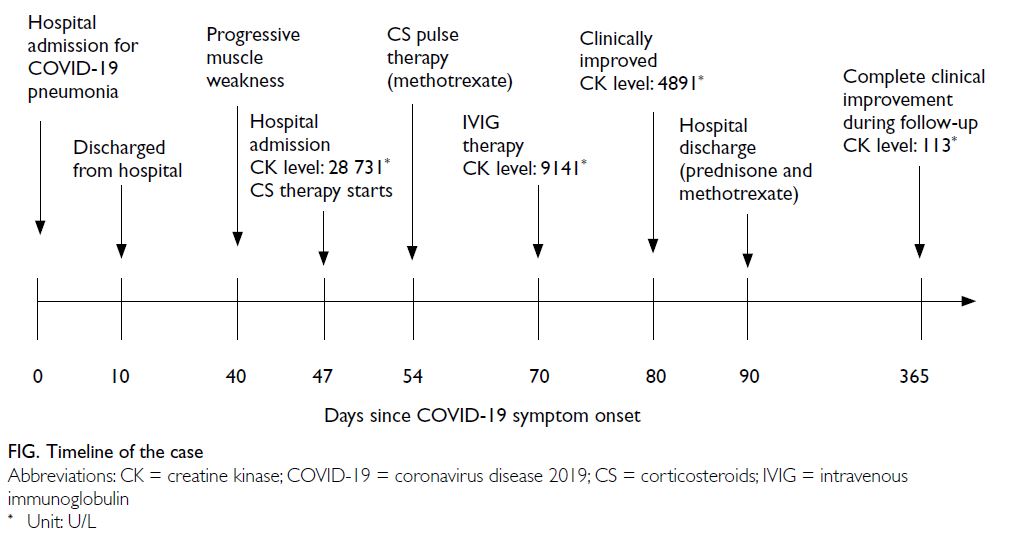

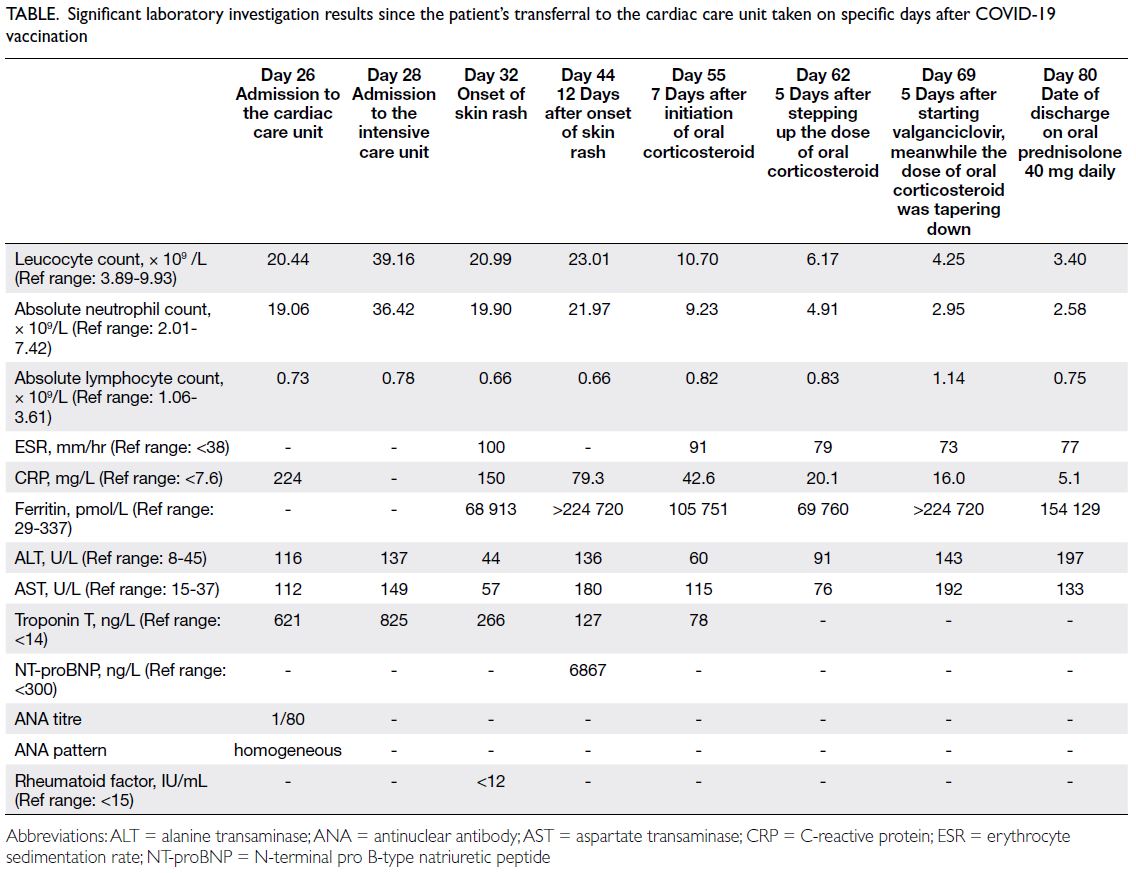

A 36-year-old female presented to the Emergency

Department of the University Clinical Centre of

Serbia in August 2020 with bilateral weakness and

aches in the proximal muscles of the upper and

lower extremities, limited limb movement, and

poor tolerance of physical exertion. Symptoms

had developed 4 weeks after hospitalisation for

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia

and progressed rapidly over the next weeks

(Fig). During her hospitalisation for COVID-19,

she was treated with the corticosteroid (CS)

methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg for 10 days, and

prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin,

azithromycin (500 mg/day for 3 days), and antipyretics. Physical examination

revealed weakness of the proximal muscles (grade

3/5) but no other abnormalities. Nasal swab

screening for severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by polymerase chain

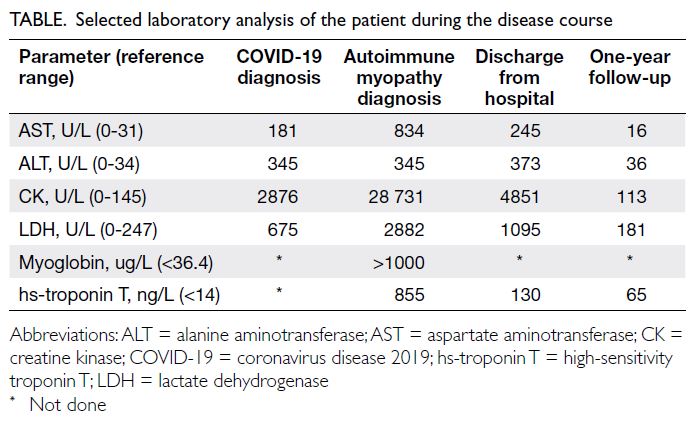

reaction test was negative. Blood work-up showed elevated levels of creatine kinase (CK) [28 731 U/L],

myoglobin, and troponin (Table). Renal function

tests were normal (blood urea nitrogen: 8.0 mmol/L,

serum creatinine: 45 μmol/L, estimated glomerular

filtration rate: >60 mL/min). Immunoserological

analysis was positive for assessment of antinuclear

antibodies (1:640) and myositis profile (Mi-2++ and Ro-52++). The patient was then referred to the

Clinic of Allergy and Immunology of the same centre

for further evaluation. Electromyoneurography of

the upper and lower extremities revealed moderate-to-severe myopathic lesions in the proximal muscles

with a pattern characteristic of inflammatory

myopathies. Testing of respiratory muscle strength

revealed decreased maximal inspiratory pressure

of 62%. Lung computed tomography scan and

echocardiography were normal. Muscle biopsy and

magnetic resonance imaging were not performed

due to temporary restrictions during the pandemic.

The remainder of a thorough work-up was normal. Autoimmune myopathy associated with COVID-19

was suspected and the patient was prescribed high-dose

CS (1 mg/kg/day) followed by pulse therapy of

500 mg/day methylprednisolone for 3 consecutive

days. Methotrexate (22.5 mg/week) was introduced.

No clinical or laboratory improvement was evident

after 2 weeks, hence intravenous immunoglobulins

(0.4 g/kg/day) were given for 5 days. This therapy

led to significant clinical improvement and a gradual

decline in muscle enzymes. During follow-up, a trial

of CS withdrawal and methotrexate dose reduction

resulted in worsening of proximal muscle weakness

and rise in serum CK. After 1 year of follow-up, the

patient remained on methotrexate 20 mg/week and

prednisone 5 mg/day. Repeated immunoserological

analysis was still positive for antinuclear antibodies

(1:640) and anti–Mi-2 antibodies.

Discussion

Myalgias, muscle weakness, and elevation of muscle

enzymes are commonly seen in COVID-19 patients,

but are typically resolved within a few weeks with

conservative treatment. Direct viral invasion of

muscles, toxic effects of cytokines and dysregulated

immune stimulation have been proposed as

possible mechanisms. There are several reports of

COVID-19–related myositis/rhabdomyolysis with

serum CK level as high as 427 656 U/L.1 2 Most

patients recover with conservative treatment. In

our patient, a mild increase in muscle enzymes was

noticed during COVID-19 infection. Nonetheless

early signs of myopathy may have been masked

by the CS therapy prescribed for COVID-19

pneumonia. Due to the presence of anti–Mi-2 and

anti–Ro-52 antibodies, which are characteristic

of dermatomyositis, we carefully examined the

skin and nailfolds, but there were no suggestive

findings at first presentation or subsequent follow-up.

A limitation of our work was the lack of muscle

histopathology or magnetic resonance imaging. Nonetheless the clinical picture, 1-year disease

course, electromyographic pattern typical of

inflammatory myopathies, and persistent positivity

for anti–Mi-2 antibodies suggest that SARS-CoV-2

infection may have triggered the development of

autoimmune myopathy in our patient.

A case of COVID-19–associated inflammatory

myopathy with severe facial, bulbar, proximal limb

weakness, and elevated CK level, suggestive muscle

biopsy and positive anti-SSA, anti–SAE-1, and

anti-Ku antibodies, has been reported. The patient

was successfully treated with a 5-day course of 1000

mg methylprednisolone.3 Nonetheless there are no

data on the subsequent clinical course.

Recently, a COVID-19–associated myopathy

caused by type I interferonopathy has been

described.4 The patient presented with general

weakness, myalgias, fever, bibasilar lung infiltrates,

and significantly elevated serum CK and troponin

levels. Immunohistochemical analysis of deltoid

muscle biopsy specimen revealed abnormal

expression of major histocompatibility complex

class I antigen on sarcolemma and sarcoplasm,

and presence of myxovirus resistance protein A on

muscle fibres and capillaries. The authors speculated

that increased expression of type I interferon was

responsible for SARS-CoV-2 myopathy in their

patient through up-regulation of proteins that are

toxic to muscle cells.4 Nonetheless deposition of

myxovirus resistance protein A in muscle fibres and

capillaries is also an early feature of dermatomyositis.

Given the lack of data on immunoserological

analysis and follow-up of the patient, an early phase

of dermatomyositis cannot be excluded.

The number of reports of autoimmune disease

developing in patients with COVID-19 is increasing.

Molecular mimicry has been proposed as a potential

mechanism.5 A recent study identified three

immunogenic linear epitopes with high sequence

identity to SARS-CoV-2 proteins in patients with

dermatomyositis, implying a possible contribution

of SARS-CoV-2 to the development of autoimmune

inflammatory myopathies.6 Additional mechanisms

may also be involved, highlighting an urgent need

to better understand the immune processes that

underlie viral-induced autoimmunity in COVID-19.

Physicians should carefully evaluate patients

who present with progressive elevation of muscle

enzymes and be alert to the possible occurrence

of autoimmune myopathy triggered by COVID-19. Early diagnosis facilitates timely initiation

of adequate treatment, preventing long-term

consequences and complications.

Author contributions

Concept or design: A Plavsic, S Arandjelovic, A Peric Popadic, S Raskovic, R Miskovic.

Acquisition of data: A Plavsic, J Bolpacic, R Miskovic.

Analysis or interpretation of data: A Plavsic, A Peric Popadic, S Raskovic, J Bolpacic, R Miskovic.

Drafting of the manuscript: A Plavsic, S Arandjelovic, J Bolpacic, R Miskovic.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: A Plavsic, J Bolpacic, R Miskovic.

Analysis or interpretation of data: A Plavsic, A Peric Popadic, S Raskovic, J Bolpacic, R Miskovic.

Drafting of the manuscript: A Plavsic, S Arandjelovic, J Bolpacic, R Miskovic.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required as per guidelines for publishing case reports of Ethics Committee of the University Clinical Centre of Serbia. Patient consent has been obtained

concerning treatment and procedures, and the patient has given written informed consent to the publication.

References

1. Beydon M, Chevalier K, Al Tabaa O, et al. Myositis as a manifestation of SARS-CoV-2. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:e42. Crossref

2. Gefen AM, Palumbo N, Nathan SK, Singer PS, Castellanos-Reyes LJ, Sethna CB. Pediatric COVID-19–associated rhabdomyolysis: a case report. Pediatr Nephrol 2020;35:1517-20. Crossref

3. Zhang H, Charmchi Z, Seidman RJ, Anziska Y, Velayudhan V, Perk J. COVID-19–associated myositis with severe proximal and bulbar weakness. Muscle Nerve 2020;62:E57-60. Crossref

4. Manzano GS, Woods JK, Amato AA. Covid-19–associated myopathy caused by type I interferonopathy. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2389-90. Crossref

5. Kanduc D. From anti–SARS-CoV-2 immune responses to COVID-19 via molecular mimicry. Antibodies (Basel) 2020;9:33. Crossref

6. Megremis S, Walker TD, He X, et al. Antibodies against immunogenic epitopes with high sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with autoimmune dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1383-6. Crossref