© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Primary omental pregnancy after intrauterine

insemination: a case report

Tony PL Yuen, MB, BS1; Winnie Hui, MRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; MK Ho, MB, BS1; Richard WC Wong, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)2

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Clinical Pathology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tony PL Yuen (ypl634@ha.org.hk)

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy (EP), a condition in which a fertilised ovum does not implant in the endometrial

cavity, occurs in 1% to 2% of all pregnancies.1 Up

to 97% of EPs occur within the fallopian tube, but

implantation can also occur at locations such as

the cervix, ovary, uterine cornua and abdomen.

Abdominal EPs are extremely rare, making up

less than 1% of EPs.1 Their presentation can be

non-specific and they are classified as primary or

secondary abdominal pregnancies. We present a

case of primary omental pregnancy with laparoscopy

and omentectomy performed.

Case summary

In January 2020, a 33-year-old gravida 1 para 0 woman

was admitted to our gynaecology unit with right-sided

abdominal pain. The patient’s past health was good

and she had no history of gynaecological surgery,

sexually transmitted disease or pelvic inflammatory

disease. She had been treated in the private sector

3 weeks before to admission with ovulation induction

and subsequent intrauterine insemination (IUI)

for coital problems. Serum beta-human chorionic

gonadotropin (HCG) was 48 mIU/L on day 18 and

768 mIU/L on day 22 after IUI. Ultrasound of the

pelvis at 5 weeks of gestation showed no intrauterine

sac. She also complained of mild per-vaginal

bleeding on admission. Abdominal examination

revealed tenderness over the right abdomen, next

to the umbilicus. Transvaginal ultrasound of the

pelvis on admission showed a linear endometrial

lining, with no adnexal masses or pelvic free fluid

identified. Blood tests showed a haemoglobin level

of 12 g/dL and beta-HCG level of 1366 mIU/mL.

Diagnostic laparoscopy was offered to the patient

in view of her abdominal pain but she opted for

beta-HCG monitoring as she was worried about a

negative laparoscopy. She subsequently complained

of severe right abdominal pain about 6 hours after

admission. Repeat transvaginal ultrasound revealed

no adnexal masses but a moderate amount of free

fluid in the pouch of Douglas. Due to the increased abdominal pain and suspicion of a ruptured EP, the

patient agreed to undergo laparoscopy.

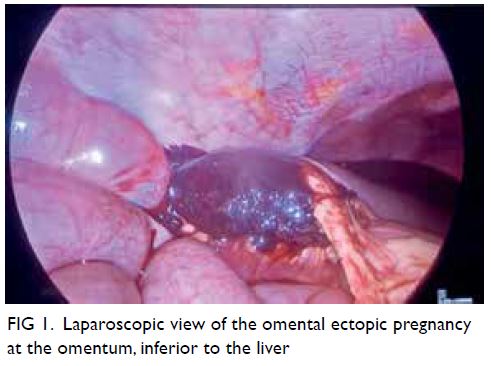

Laparoscopy showed haemoperitoneum of

200 mL and a normal uterus, bilateral fallopian tubes

and ovaries. Survey of the peritoneal cavity revealed

a 5 × 5 cm haematoma attached to the omentum at

the right hepatic flexure, with mild oozing from the

site of attachment (Fig 1). The rest of the abdomen

was unremarkable. General surgeons were consulted

and omentectomy (including the site of bleeding)

was performed.

The patient made an uneventful postoperative

recovery and haemoglobin was stable. She was

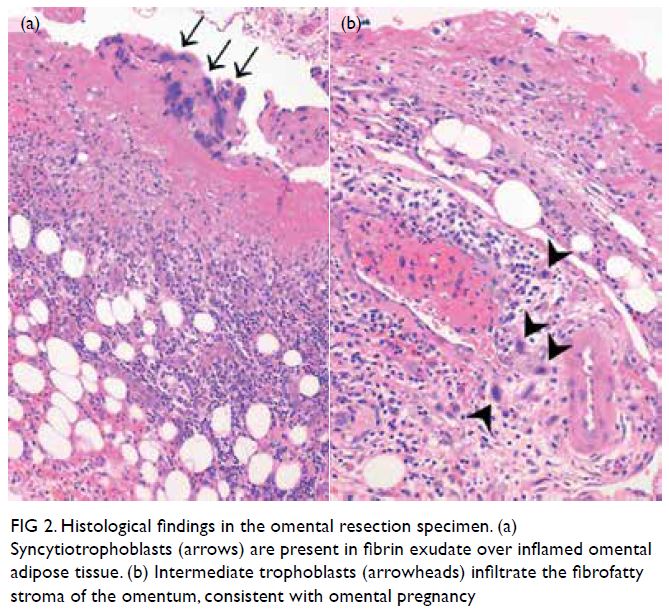

discharged on day 4 after surgery. Pathological

examination revealed products of gestation mixed

with inflammatory and reactive mesothelial cells

(Fig 2). Beta-HCG monitoring after surgery

showed a satisfactory drop to a non-pregnant level:

366 mIU/mL, 144 mIU/mL, and 1.7 mIU/mL on

days 2, 4, and 18 after surgery.

Figure 2. Histological findings in the omental resection specimen. (a) Syncytiotrophoblasts (arrows) are present in fibrin exudate over inflamed omental adipose tissue. (b) Intermediate trophoblasts (arrowheads) infiltrate the fibrofatty stroma of the omentum, consistent with omental pregnancy

Discussion

Among EPs, abdominal pregnancy is most rare. They

have been classified as either primary or secondary.

Our case meets the criteria established by Studdiford2

for a primary abdominal pregnancy: normal, bilateral

fallopian tubes and ovaries with no recent or remote

injury; absence of any uteroperitoneal fistula; and

presence of a pregnancy related exclusively to the

peritoneal surface and diagnosed early enough to

exclude the possibility of secondary implantation

after primary nidation elsewhere.

Early preoperative diagnosis of an abdominal

EP is very difficult in many cases. A systematic

review by Poole et al3 showed that among patients

with a final diagnosis of omental EP, none had a

preoperative diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy. As

a result of the diagnostic difficulty, there is usually

a delay from presentation to definitive treatment

with some cases requiring diagnosis by serial HCG

monitoring supplemented with magnetic resonance

imaging. A high level of vigilance is therefore vital

when monitoring the symptoms and vital signs of a suspected case, and early surgical intervention should

be considered if there is clinical deterioration. In our

case, we elected to perform emergent laparoscopy in

view of increased abdominal pain and free fluid in

the pouch of Douglas.

Laparotomy with excision of the embryo

has been the classic management for abdominal

pregnancy.4 However, with its widespread availability,

laparoscopy should be the modality of choice,

especially when the patient is haemodynamically

stable, as in our case, and the required expertise is

available. Laparoscopic management is associated

with fewer morbidities, reduced intraoperative blood

loss and a shorter hospital stay. The importance of

a general peritoneal survey is paramount; in cases

of normal fallopian tubes and ovaries, extra care

must be taken not to miss an EP elsewhere in the

peritoneum and prematurely commit to a negative

laparoscopy. If a difficult resection is encountered,

the expertise of a general surgeon will be of benefit.

Alternatives to surgical treatment have also been

reported,3 such as intralesional methotrexate,

intramuscular methotrexate, intracardiac potassium

chloride injection and artery embolisation. However,

the prerequisites for non-surgical treatment

include reliable imaging and for the patient to be

haemodynamically stable.

Assisted reproductive techniques are known

to be associated with an increased risk of EP.

Some reports state an incidence of up to 4.5% with

assisted reproductive technology compared with

a spontaneous pregnancy.5 With regard to IUI, the

incidence of EP is reported to be 2.05% compared

with 3.33% for in vitro fertilisation. A higher risk

of EP is also associated with stimulated cycles

(compared with natural cycles: 2.62% vs 0.99%) and

use of husband sperm (compared with donor sperm:

3.54% vs 1.08%). Many postulations have been made

regarding the mechanism of an abdominal EP.3 As

ovarian induction was performed in this case, the risk

of EP was increased. In the setting of IUI, it is possible

that the fertilised embryo develops as a primary tubal

pregnancy that subsequently passes through the

fimbrial end and implants into the omentum.

Although omental EPs are extremely rare, and

in our case, the first of such a condition found after

IUI, clinical suspicion must be high in a patient who

presents with symptoms suggestive of EP but with

normal uterus and adnexa during intraoperative

exploration. Clinicians should always be vigilant with

regard to the patient’s clinical condition, and there

should be a low threshold for surgical intervention

if clinical deterioration is noted. In addition, with

the rising application of assisted reproductive

technology, the risk of EPs, and by extension the

risk of abdominal EPs, is also increased, making

the diagnosis and treatment of this potentially life-threatening

condition evermore challenging.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the report, acquisition

of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained for all treatment involved as well as for publication of this article and

accompanying images.

References

1. Fylstra DL. Ectopic pregnancy not within the (distal)

fallopian tube: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:289-99. Crossref

2. Studdiford WE. Primary peritoneal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1942;44:487-91. Crossref

3. Poole A, Haas D, Magann EF. Early abdominal ectopic

pregnancies: a systematic review of the literature. Gynecol

Obstet Invest 2012;74:249-60. Crossref

4. Yip SL, Tan WK, Tan LK. Primary omental pregnancy. BMJ

Case Rep 2016;2016: bcr2016217327. Crossref

5. Bu Z, Xiong Y, Wang K, Sun Y. Risk factors for ectopic

pregnancy in assisted reproductive technology: a 6-year,

single-center study. Fertil Steril 2016;106:90-4. Crossref