Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy for delayed

gastric conduit emptying after pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy: a case report

Fion SY Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Ian YH Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Desmond KK Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Claudia LY Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Betty TT Law, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Velda LY Chow, MS, FHKAM (Surgery)2; Simon Law, PhD, MS1

1 Division of Esophageal and Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery, Department of Surgery, School of Clinical Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Division of Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Surgery, School of Clinical Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Simon Law (slaw@hku.hk)

Case report

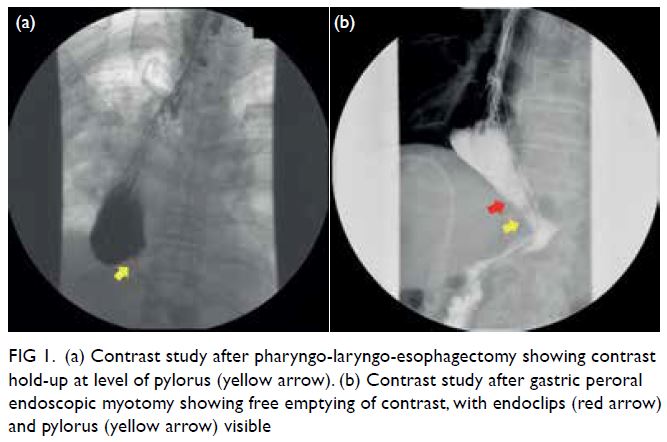

In September 2016, a 64-year-old man with

intrathoracic oesophageal cancer underwent

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and minimally

invasive esophagectomy with no pyloroplasty.

The gastric conduit was placed in the posterior

mediastinum. Pathology revealed a moderately

differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (ypT2N1M0)

with clear margins. One year later he underwent

surgery for isolated right cervical lymph node

recurrence and tolerated a normal diet after surgery

with no gastrointestinal symptoms. At 22 months

after the second surgery, the patient developed

dysphagia and a cervical oesophageal cancer

was identified. Completion pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy

(PLE) with resection of the residual

cervical oesophagus, pharyngo-laryngectomy, and

reconstruction with a segment of free jejunum

interposed between the neopharynx and gastric

conduit was performed. After surgery, the patient developed delayed gastric conduit emptying (DGCE)

and reported regurgitation of undigested food soon

after diet introduction. There was a persistently high

nasogastric output, and non-ionic contrast study

showed hold-up of contrast at the level of pylorus

(Fig 1a). The patient’s symptoms persisted and he

relied on nasoduodenal feeding despite prokinetic

agents and pyloric balloon dilatation.

Figure 1. (a) Contrast study after pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy showing contrast hold-up at level of pylorus (yellow arrow). (b) Contrast study after gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy showing free emptying of contrast, with endoclips (red arrow) and pylorus (yellow arrow) visible

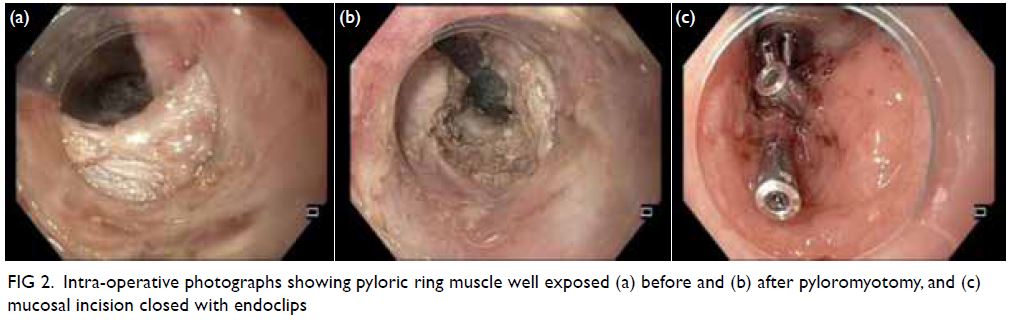

Gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy

(G-POEM) was performed in February 2020,

4 months after completion PLE. The procedure was

performed with the patient in a supine position

and under general anaesthesia with endotracheal

intubation via end tracheostomy. A high-definition

gastroscope (GIF-H190; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan)

fitted with a conical shaped transparent cap (DH-28GR; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) and carbon dioxide

insufflation were used. After submucosal injection of

a mixture of normal saline and indigo carmine at the

posterior wall of the gastric conduit, 5 cm proximal to

the pylorus, a 2-cm longitudinal mucosal incision was

made with DualKnife J (Olympus) using Endocut Q

mode (effect 3, cut-duration 2, cut-interval 4) [VIO®

300D; Erbe, Tübingen, Germany]. The endoscope

entered the submucosal space to dissect a tunnel

caudally until the pyloric ring was well exposed

(Fig 2a). Pyloromyotomy was performed and the

circular muscle ring completely divided and flattened

(Fig 2b). Haemostasis was achieved and the mucosal

opening closed with repositioning clips (Single Use

Hemoclip; Mednova, Zhejiang, China) [Fig 2c]. The

surgery time was 120 minutes and rapid contrast

passage to the duodenum was demonstrated on

postoperative contrast study (Fig 1b). He resumed

an oral diet thereafter.

Figure 2. Intra-operative photographs showing pyloric ring muscle well exposed (a) before and (b) after pyloromyotomy, and (c) mucosal incision closed with endoclips

Discussion

Pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy was first

reported by Ong and Lee in 19601 and is regarded

as standard treatment for hypopharyngeal and cervical oesophageal cancer. Chemoradiotherapy

has gained popularity as an alternative therapeutic

strategy to preserve the larynx, but salvage PLE

due to incomplete response or cancer recurrence

is not uncommonly required.2 Post-PLE DGCE is

underreported and the incidence is unknown. Patients

frequently complain of bloating, regurgitation, and

poor oral intake. According to unpublished results

from our prospectively collected database, DGCE

was documented in five of 20 patients with PLE for

cervical oesophageal cancer over the past 10 years.

Of these five patients, pyloroplasty was performed in

two, of whom symptoms improved with prokinetic

agents alone in one, and endoscopic pyloric balloon

dilation was required in the other. For those without

pyloric drainage, two patients were managed by

G-POEM. The remaining patient was an 83-year-old

man on prolonged tube feeding who had pneumonia

and died 10 weeks after the surgery.

The pathogenesis of DGCE after PLE may

differ to that after oesophagectomy without

pharyngo-laryngectomy although data are lacking.

Experience in the management of DGCE after

oesophagectomy (without pharyngo-laryngectomy)

serves to guide treatment of post-PLE DGCE.

Proposed contributing factors include gastropyloric

denervation, dysfunctional gastric peristalsis and

use of the whole stomach for reconstruction.3 4

The application of G-POEM in PLE patients

has not been reported. We report a patient with prior

oesophagectomy who developed DGCE only after

completion PLE. Symptoms resolved after G-POEM.

We postulate that removal of the upper oesophageal

sphincter in PLE limits build-up of intragastric

pressure, compounding DGCE. Pyloromyotomy

reduces pyloric channel pressure and expedites

gastric emptying, G-POEM accomplishes this as

a minimally invasive method. We hypothesise that

gastric conduit emptying after PLE can be viewed as

a two-stage process. In the first stage, the food bolus passes passively from the proximal stomach to the

antrum. In the second stage, food is evacuated from

the antrum through the pylorus to the duodenum.

A sufficient pressure gradient within the gastric

conduit is required to overcome pyloric resistance.

Resection of the pharynx and larynx results in

equalisation of pressure between the gastric conduit

and the atmosphere. The stomach is also exposed

to negative intrathoracic pressure. The outflow

resistance due to the intact pylorus assumes more

importance after PLE since the paretic stomach

fails to build up internal pressure. This explains

why symptoms of delayed emptying in our patient

emerged only after the pharyngo-laryngectomy, not

after the initial oesophagectomy.

Pyloroplasty and pyloromyotomy have both

been shown effective and safe drainage procedures

for gastric conduit after oesophagectomy.5 The

G-POEM disrupts the pylorus and improves

gastric emptying, theoretically achieving the same

outcome and serving as a salvage option for DGCE

after PLE. We perform G-POEM according to the

same principle applied to POEM for achalasia. The

submucosal tunnel is dissected close to the muscle

layer for precise pyloromyotomy. Secure mucosal

closure permits early diet resumption. However,

the aim of pyloromyotomy is to overcome the

outlet obstruction without alleviating gastroparesis.

Despite improved gastric emptying, symptoms of

our patient were not completely eliminated. Patients

need to make dietary adjustments to accommodate

the new conduit over time while maintaining

satisfactory nutrition and body weight.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

report of successful management of DGCE after

PLE by G-POEM. A pyloric drainage procedure is

advocated since resection of the upper oesophageal

sphincter, an integral part of PLE, limits pressure

build-up and food emptying within the gastric

conduit.

Author contributions

Concept or design: FSY Chan, S Law.

Acquisition of data: FSY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: FSY Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: FSY Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: FSY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: FSY Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: FSY Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, VLY Chow was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency

in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong

West Cluster (Ref: UW 16-2023). Consent from patient was

obtained.

References

1. Ong GB, Lee TC. Pharyngogastric anastomosis after

oesophago-pharyngectomy for carcinoma of the

hypopharynx and cervical oesophagus. Br J Surg

1960;48:193-200. Crossref

2. Tong DK, Law S, Kwong DL, Wei WI, Ng RW, Wong KH.

Current management of cervical esophageal cancer. World

J Surg 2011;35:600-7. Crossref

3. Konradsson M, Nilsson M. Delayed emptying of the gastric

conduit after esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:S835-44. Crossref

4. Akkerman RD, Haverkamp L, van Hillegersberg R,

Ruurda JP. Surgical techniques to prevent delayed gastric

emptying after esophagectomy with gastric interposition: a

systematic review. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:1512-9. Crossref

5. Law S, Cheung MC, Fok M, Chu KM, Wong J. Pyloroplasty and pyloromyotomy in gastric replacement of the

esophagus after esophagectomy: a randomized controlled

trial. J Am Coll Surg 1997;184:630-6.