Fulminant necrotising amoebic colitis: a report of two cases

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Fulminant necrotising amoebic colitis: a report

of two cases

LM Tam, MB, BS1; KC Ng, MB, BS, FRCS1; CH Man, MB, BS FRCS1; FY Cheng, MB, BS2; Y Gao, LMCHK2

1 Department of Surgery, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr LM Tam (tammy520@connect.hku.hk)

Case report

Case 1

In January 2019, a 31-year-old man with a history

of amphetamine abuse presented with a 10-day

history of watery diarrhoea and abdominal pain. On

admission, he had a fever of 38.1°C and tachycardia

but normal blood pressure. Abdominal examination

revealed tenderness and guarding over the lower

abdomen. The patient was resuscitated and

intravenous antibiotics prescribed since an infective

cause was considered most likely. Abdominal

plain radiograph showed grossly dilated small and

especially large bowel (diameter up to 9 cm). White

cell count was 22×109/L (neutrophil differential

count 19×109/L), liver and renal function were

unremarkable. Contrast computed tomography (CT)

scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed extensive

colitis, suggesting pseudomembranous colitis or

diffuse colitis. Stool culture for Clostridium difficile

was negative and stool microscopy revealed no ova

or cysts. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),

hepatitis B and C virus serologies were non-reactive.

He was treated as pseudomembranous colitis by

the medical gastrointestinal team and commenced

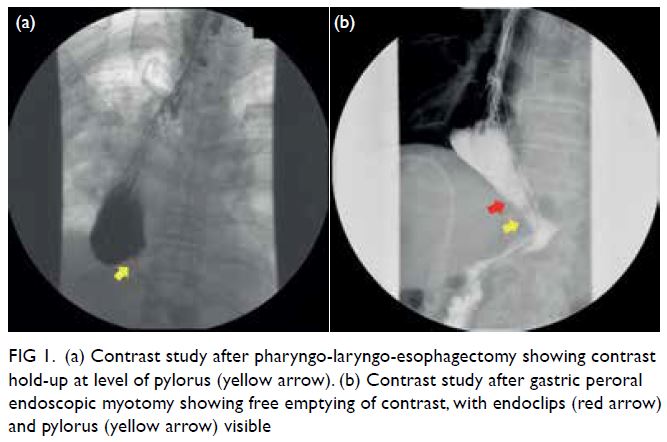

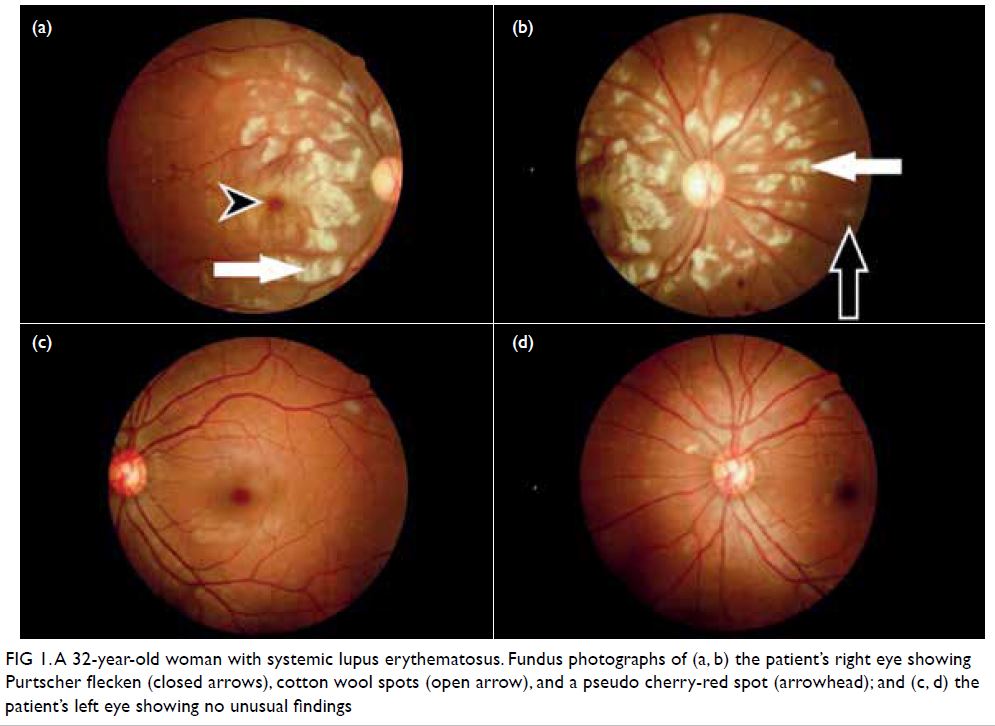

on oral vancomycin. Later sigmoidoscopy revealed

inflamed mucosa with multiple ulcers, especially at

the sigmoid colon (Fig 1). Biopsies were taken. The

patient’s condition deteriorated and he developed

septic shock. A new contrast CT scan showed

pneumoperitoneum. Emergency laparotomy was performed and revealed generalised faecal peritonitis

with the whole colon necrosed and communicating

with the peritoneal cavity. Debridement of necrotic

tissue and multiple segmental resections of bowel

with end ileostomy were performed in stages.

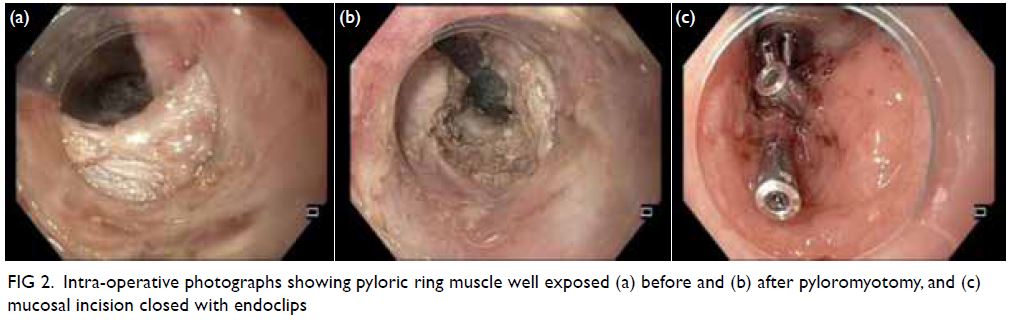

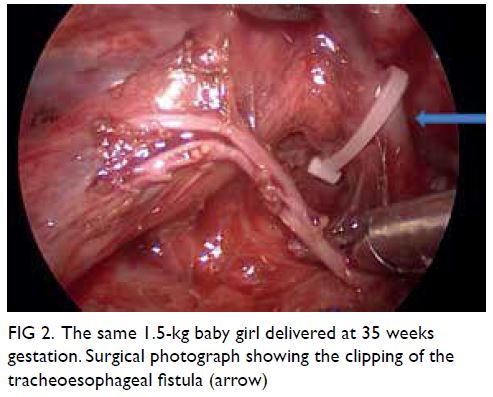

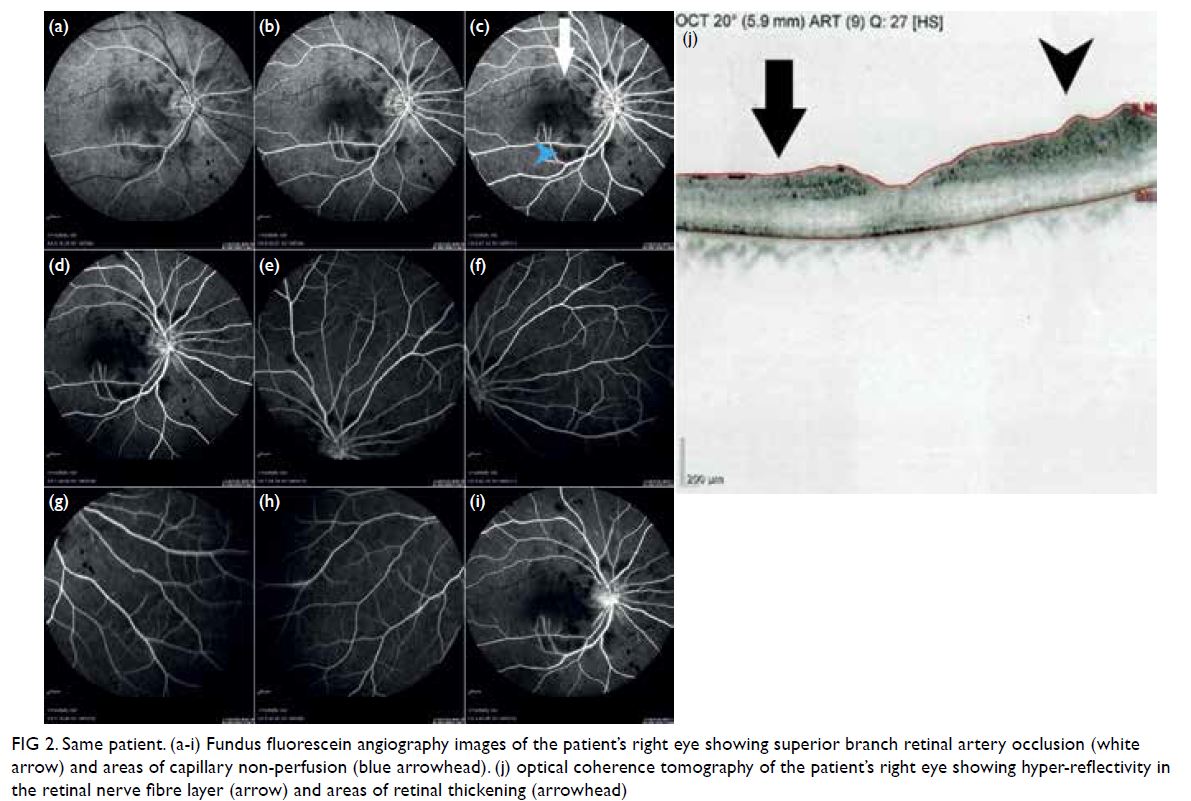

The diagnosis of fulminant amoebic colitis (FAC)

was made on histopathological evaluation of the

biopsy and resection specimen (Fig 2). Antibiotics

were switched to metronidazole accordingly. The

patient’s condition was later complicated by an

intra-abdominal fluid collection and image guided

drainage was performed. He was initially nursed

in the intensive care unit and then transferred to a

surgical ward for rehabilitation. He was discharged

from hospital 4 months later.

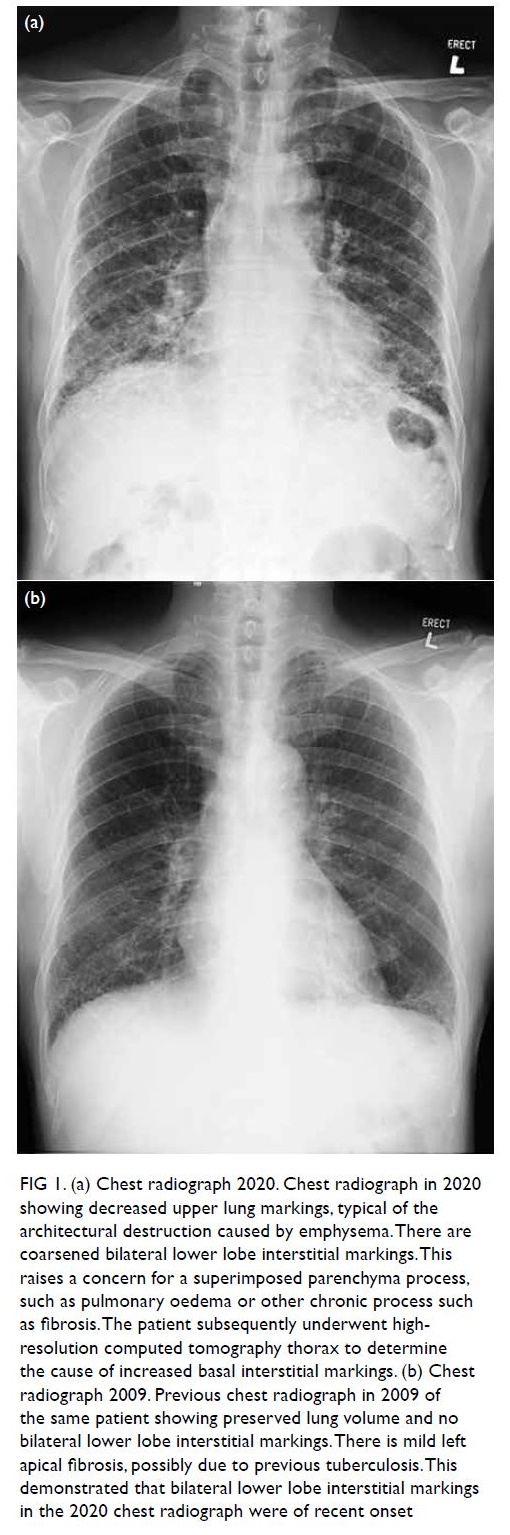

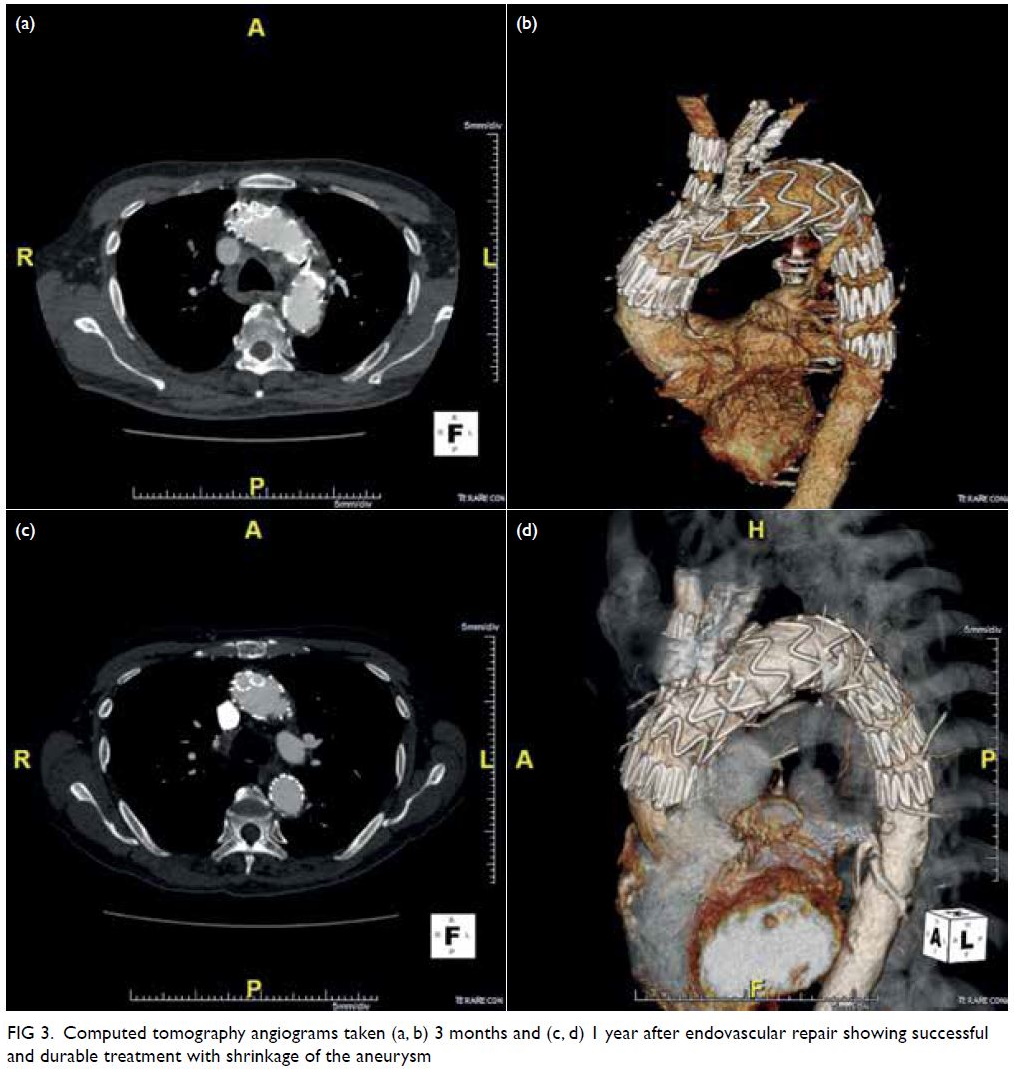

Figure 2. Histological examinations from Case 1. (a) Perforated ulcer. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain ×100. (b) Amoebae labelled with arrows in the lamina propria. H&E stain ×100

Case 2

In February 2020, a 61-year-old man presented with

a ≥1-week history of diarrhoea, abdominal pain,

high fever of 39°C and tachycardia with normal

blood pressure. Abdominal examination showed

diffuse tenderness, but without peritoneal signs.

The patient’s medical history was otherwise good,

and initial investigations including blood tests and

plain radiographs were all unremarkable. In view

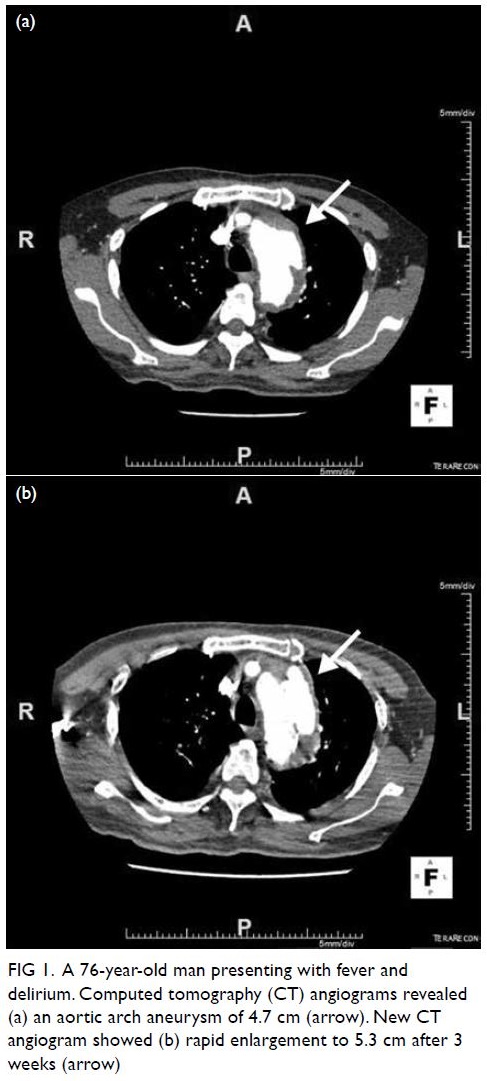

of the progressive abdominal distension, urgent

contrast CT was arranged and showed a suspected

perforated caecum. Emergency surgery found

ischaemic colon extending from the caecum to

mid sigmoid, with perforations over the proximal transverse colon and hepatic flexure. Subtotal

colectomy with end ileostomy was performed.

He was transferred to the intensive care unit after

surgery and required vasopressor and continuous

venovenous haemofiltration due to severe sepsis.

He showed a good response and was weaned

off vasopressor support on postoperative day 4.

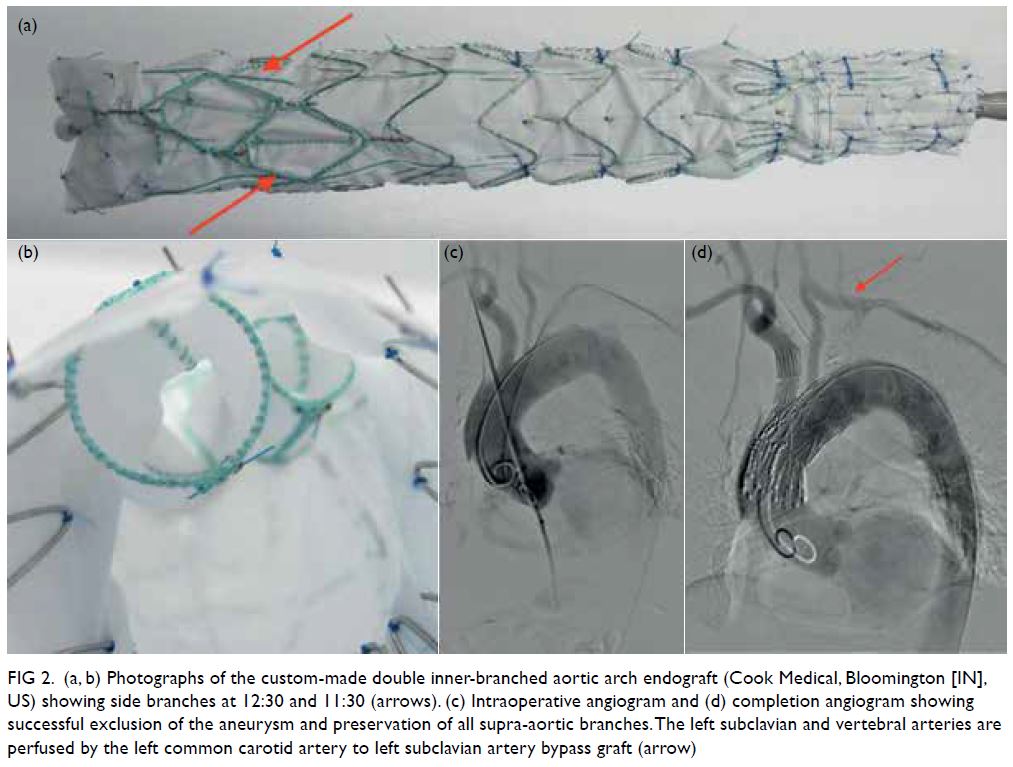

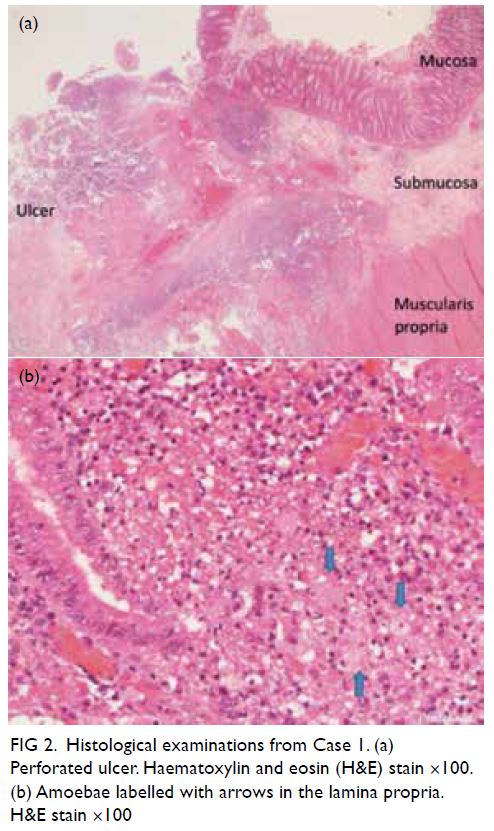

Pathology of the surgical specimen later confirmed

amoebic colitis with extensive ulcer and perforation

(Fig 3). There were no features of atherosclerosis,

vasculitis, thromboembolism, or inflammatory

bowel disease. Microscopic results were also

available after surgery. Stool culture for C difficile,

stool microscopy for amoeba, stool microscopy for

ova or cysts, stool polymerase chain reaction for

virus, and HIV serology test results were all negative,

but Entamoeba histolytica serology test was positive.

He was prescribed metronidazole for 14 days and

then oral diloxanide furoate for 10 days as suggested

by the microbiologist. The patient’s recovery

was later complicated by wound dehiscence and

abdominal cocoon. Repeat surgery for debridement

was performed and skin closure changed to an

ABTHERA temporary abdominal closure system.

The patient recovered gradually and was transferred

to a rehabilitation unit 3 months after surgery.

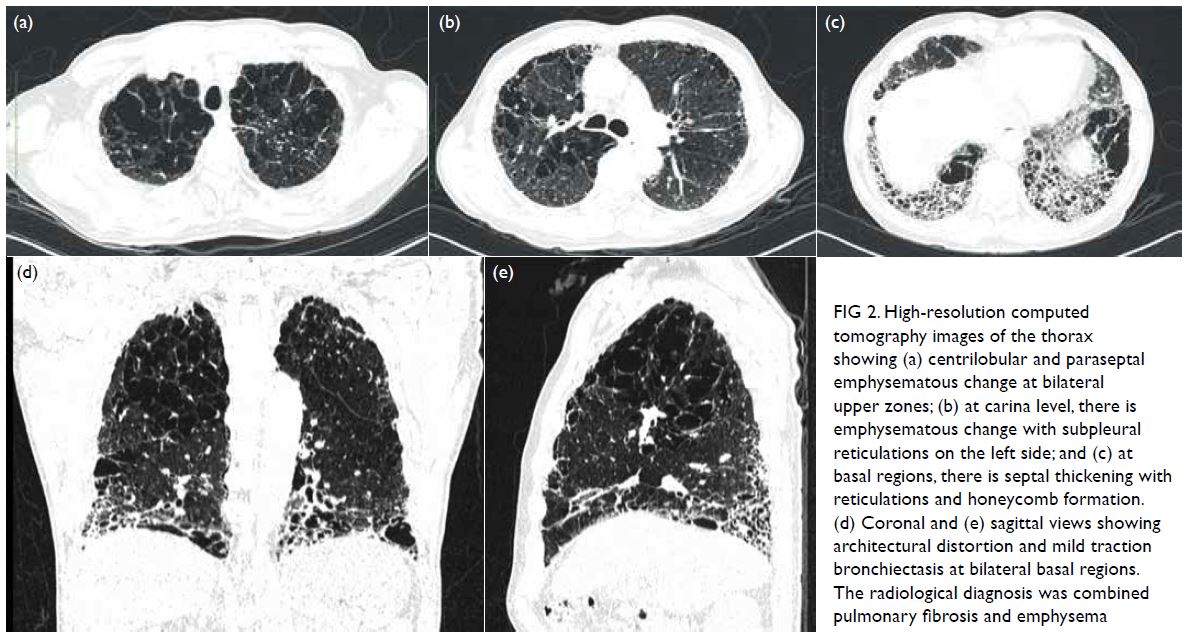

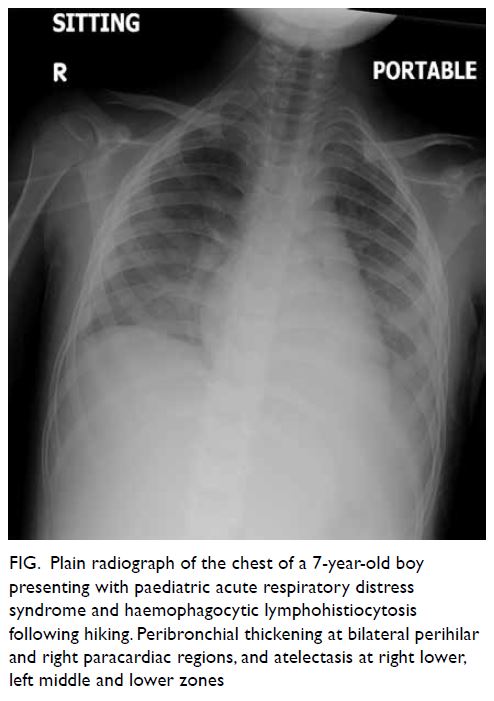

Figure 3. Histological examinations from Case 2. (a) Presence of Entamoeba histolytica, stained purple due to glycogen content, in necrotic ulcer debris. Periodic acid-Schiff ×200. (b) Deep penetrating ulcer, with extensive necrosis, down to the muscularis propria. H&E stain ×10

Discussion

Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite and

the cause of amoebiasis in humans.1 Early diagnosis

and treatment are essential to avoid progression to

fulminant colitis. Amoebic dysentery is classified

as a notifiable disease in Hong Kong. Prevalence of

amoebiasis is higher in developing countries such

as India, Mexico, and parts of Central and South

America,2 mainly related to poor socioeconomic and

sanitary conditions. In developed countries, where

faecal-oral transmission is unusual, amoebiasis is

more often seen in immigrants from or individuals

with a travel history to endemic areas. Other groups

at risk include male homosexuals3 with or without

HIV, infants, pregnant women, and those taking

immunosuppressants, especially corticosteroids.1

Neither of our two cases had a relevant travel history

in the past year, and they presented several months

apart, so they are unlikely to be imported cases or to have had the same source of infection. Case 1

had some risk factors for amoebiasis: he was a male

homosexual living in rental housing with shared

rooms. A detailed history taking from patients who

present with severe diarrhoea is crucial. Prompt

initiation of anti-amoebic treatment should be

considered in cases where there is a high index of

suspicion.

Although E histolytica can be cultured in vitro, this is neither routinely performed nor is it a gold

standard in the diagnosis of amoebic colitis because

amoebic culture is insensitive (25%). The most

commonly used laboratory test is stool microscopy

to identify trophozoites or cysts, although this also

has low sensitivity (<60%) and specificity (10%-50%).

As exemplified by our two cases, both had negative

stool microscopy. In some laboratories, stool

antigen detection of E histolytica might be available.

However, neither stool microscopy (in the absence

of ingested erythrocytes in the trophozoites) nor

some antigen detection kits can distinguish between

pathogenic E histolytica and commensal Entamoeba

dispar. Serum antibody is commonly positive in

patients with invasive amoebiasis,4 especially in

endemic areas. It may be difficult to differentiate past

from active infection since antibodies may persist for

some time. Recent commercially available multiplex

polymerase chain reaction systems offer a rapid and

sensitive way of detecting E histolytica DNA in stool;

however, cost and availability limit their application

in most patients.

Another popular non-invasive investigation is

different modalities of imaging, especially contrast

CT scan. Some CT features specific to amoebic

colitis have been reported. These include extended

submucosal ulcers with intramural dissection

caused by flask-shaped ulcers typical of amoebiasis

and omental “wrapping” indicating adhesions

with neovascularisation due to ischaemic foci of

transmural amoebic colitis.5 Other non-specific

findings include pancolitis with areas of target signs,

discontinuous bowel necrosis and coexistence of liver

abscess. None of these features were evident on CT

scans in our patients. In clinical practice, CT scan is

not sensitive and has a small role in diagnosing FAC.

It is mainly used to distinguish the severity of colitis,

looking for complications such as bowel perforation

or ischaemia.

Sigmoidoscopy and/or colonoscopy with

biopsy can also be performed as a diagnostic tool.

However, there is a high risk of perforation, especially

of inflamed or even ischaemic bowel. We do not

recommend endoscopic investigations in cases of

severe colitis or in patients with high fever.

Preoperative diagnosis of FAC remains a

challenge and detailed history taking plays an

important role in identifying high-risk cases.

Mild cases of amoebic colitis can be treated

medically with metronidazole to control systemic

invasion and diloxanide furoate, a luminal agent, in

addition to eliminating luminal cysts. If the condition becomes transmural, conservative treatment is no

longer appropriate. Early diagnosis and extensive

surgical treatment are important to reduce

morbidity and mortality.1 In both our cases, with

both complicated by bowel perforation, extensive

bowel resection was immediately performed.

Intra-operatively, skipped lesions with multiple

transmural perforations of bowel were noticed.

However, some gross features make differentiation

from other pathology difficult, especially Crohn’s

disease. In our patients, necrotic tissue was more

friable with little bleeding from the necrotic bowel

wall. These features are quite unique compared

with other causes of bowel ischaemia. This may be

related to severe necrosis with consequent poor

vascular supply to the bowel. In the worst case,

the necrotic bowel wall communicates with the

peritoneal cavity, making bowel resection more

difficult as the dissection planes may be disrupted.

Therefore, extensive debridement of necrotic tissue

or even staged operations are required. Special gross

features of FAC are seldom mentioned in other case

reports. Early identification of these features enables

early commencement of empirical anti-amoebic

treatment and aids the recovery of patients.

Author contributions

Concept or design: LM Tam, KC Ng, CH Man.

Acquisition of data: LM Tam

Analysis or interpretation of data: LM Tam, FY Cheng, Y Gao.

Drafting of the manuscript: LM Tam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KC Ng, CH Man.

Acquisition of data: LM Tam

Analysis or interpretation of data: LM Tam, FY Cheng, Y Gao.

Drafting of the manuscript: LM Tam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KC Ng, CH Man.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. The patients provided verbal informed consent

for the treatment/procedures and consent for publication.

References

1. Stanley SL Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet 2003;361:1025-34. Crossref

2. Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA Jr. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1565-73. Crossref

3. Roure S, Valerio L, Soldevila L, et al. Approach to

amoebic colitis: epidemiological, clinical and diagnostic

considerations in a non-endemic context (Barcelona, 2007-2017). PLoS One 2019;14:e0212791. Crossref

4. Tanyuksel M, Petri WA Jr. Laboratory diagnosis of

amebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003;16:713-29. Crossref

5. Kinoo SM, Ramkelawon VV, Maharajh J, Singh B. Fulminant

amoebic colitis in the era of computed tomography scan:

a case report and review of the literature. SA J Radiol

2018;22:1354. Crossref