Sevelamer crystal–associated peritonitis in a patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2023 Aug;29(4):349–50 | Epub 4 Aug 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Sevelamer crystal–associated peritonitis in a patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: a case report

YH Wong, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; SM Li, B Pharm, MSc2; Will WL Pak, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; KL Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Z Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; WP Law, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; CK Lam, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Sunny SH Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Pharmacy Department, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr YH Wong (wyh114@ha.org.hk)

Case report

A 60-year-old Chinese lady was admitted in August

2019 with fever, abdominal pain, and turbid peritoneal

dialysate effluent. She had a history of end-stage

renal disease due to immunoglobulin A nephropathy

and had been on continuous ambulatory peritoneal

dialysis for 3 years. Her usual medication included

aspirin, calcitriol, cetirizine, ferrous sulphate,

metoprolol, mirtazapine, pantoprazole, pregabalin,

and sevelamer carbonate (1600 mg three times a

day). Peritoneal dialysate fluid grew Escherichia coli,

and intra-peritoneal gentamicin and ceftazidime

were started. Her peritoneal dialysis catheter was

removed 1 week later due to refractory peritonitis,

but her abdominal pain persisted with development

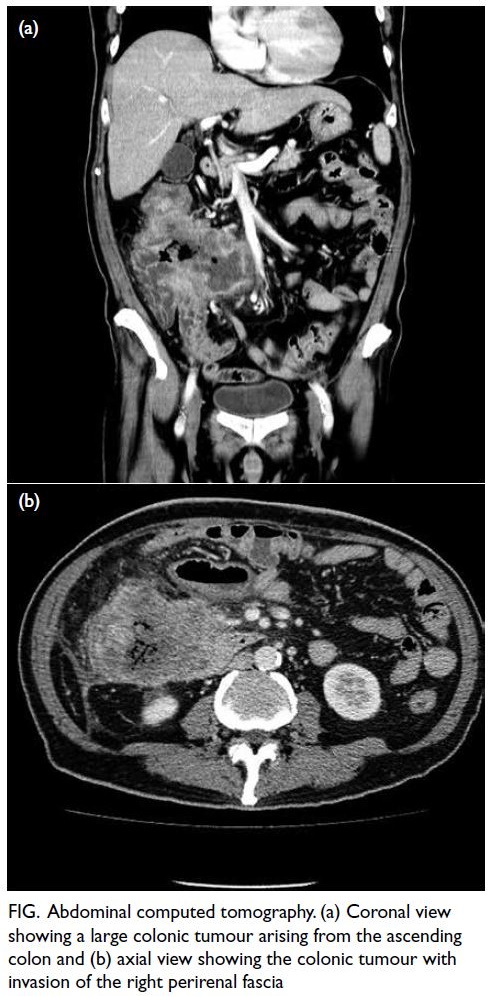

of paralytic ileus. A contrast computed tomography

scan of abdomen performed 2 days following catheter

removal revealed gross pneumoperitoneum and

mural thickening over the small bowel. Laparotomy

was performed and a proximal descending colonic

ulcer with 2-mm perforation was identified. The

patient underwent a left hemicolectomy but later

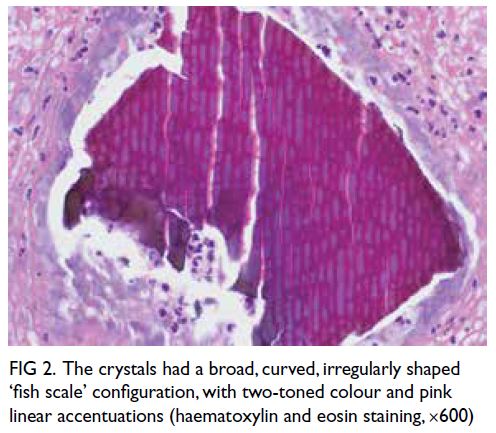

succumbed in the intensive care unit due to hospital-acquired

pneumonia.

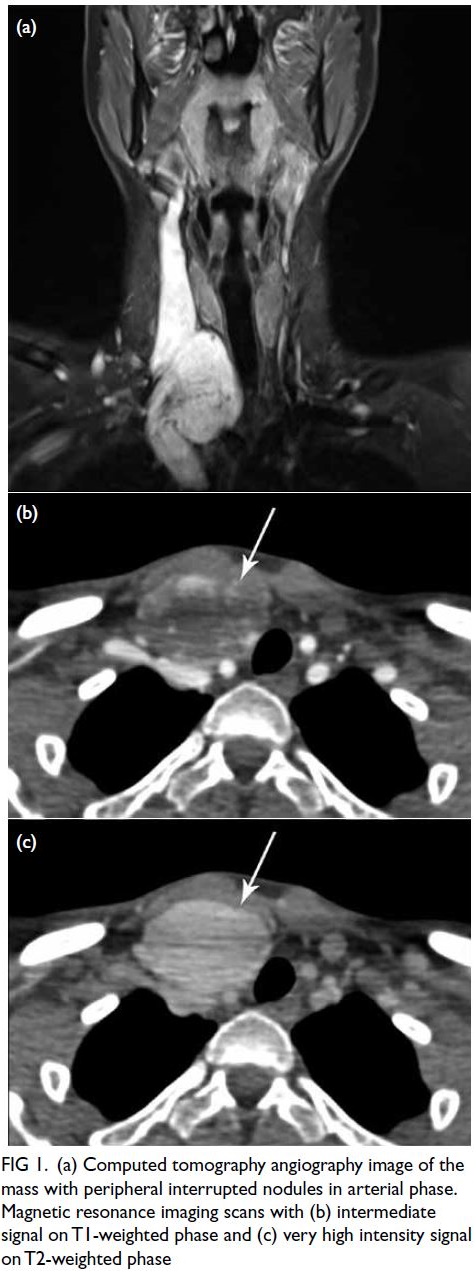

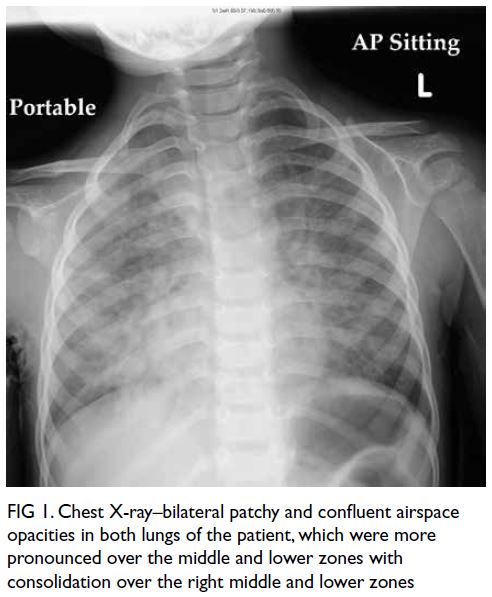

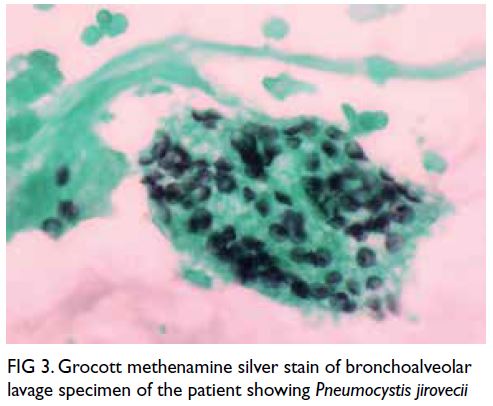

An analysis of the colonic specimen

demonstrated full thickness necrosis of the colonic

wall with associated acute suppurative inflammation

and peripheral ulceration. Incidentally there were

abundant polygonal, non-refractile crystals with

a brown, fish-scale configuration in the necrotic

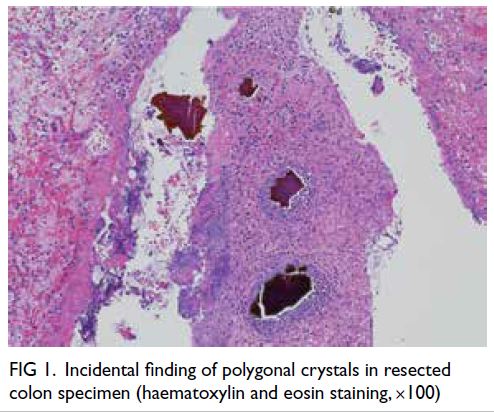

debris (Fig 1). The crystals appeared violet on

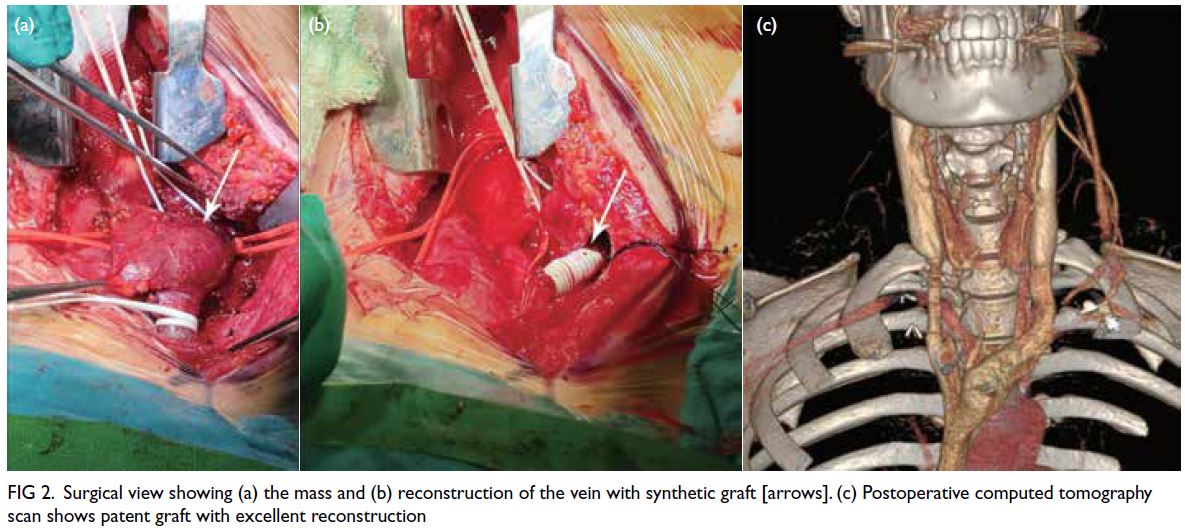

periodic acid–Schiff stain staining. On haematoxylin

and eosin staining, they had a two-toned colour

imparted by pink linear accentuations (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Incidental finding of polygonal crystals in resected colon specimen (haematoxylin and eosin staining, ×100)

Figure 2. The crystals had a broad, curved, irregularly shaped ‘fish scale’ configuration, with two-toned colour and pink linear accentuations (haematoxylin and eosin staining, ×600)

Discussion

Sevelamer is a calcium-free anion-exchange resin

prescribed as a phosphate binder in patients with

chronic kidney disease. It is composed of a non-absorbable

hydrogel with ammonia on a carbon

backbone. Stomach acid releases sevelamer polymer that binds phosphate in the intestine and forms

a crystalline aggregate.1 Initially approved by the

United States Food and Drug Administration

in October 1998 as sevelamer hydrochloride,

sevelamer has been largely replaced since 2007 by sevelamer carbonate.1 Sevelamer is commonly

associated with gastrointestinal (GI) tract side-effects

such as dyspepsia, abdominal pain, flatulence,

and constipation.2 Sevelamer crystals (SCs) are

non-polarised, have a broad curved and irregularly

spaced fish-scale pattern, appear violet on periodic

acid–Schiff staining, and have a two-tone yellowish/brownish colour on haematoxylin and eosin

staining.1 About 19 cases of sevelamer-associated

GI ulcers have been reported in the literature.3

The lesion can be found in all segments of the GI

tract although the colon is the most common site.

Sevelamer crystals are usually found inside the GI

tract mucosa.2 Endoscopic findings include erosions

and ulcerations, pseudo-inflammatory polyps and

bezoar. Although a dose-dependent association had

been reported, a recent review could not confirm the

association.2 In one case report, a colonic mucosal

ulcer developed while taking sevelamer carbonate

800 mg three times a day (duration not known).4 In

another case report, a recto-sigmoid ulcer developed

after taking sevelamer carbonate 1600 mg three

times a day for 2 months.5 Diabetic patients appeared

to be more prone to SC-associated GI lesions.2 They

developed SC-associated GI lesions with a smaller

dose compared with non-diabetics. Most reported

cases required discontinuation of sevelamer,3 6 7

although improvement in clinical condition and

cessation of rectal bleeding following dose reduction

were reported in one case.2

In our patient, there were two possible

explanations for her clinical course. She may

have developed severe continuous ambulatory

peritoneal dialysis peritonitis as a primary disease

with secondary paralytic ileus, predisposing to SC

deposition in the GI tract mucosa. Alternatively, she

may have sustained GI tract injury by SC leading to

colonic perforation and secondary peritonitis.

To the best of our knowledge, SC has not been

previously reported to present with continuous

ambulatory peritoneal dialysis peritonitis. The

treating physician must be vigilant for potential

complications of sevelamer prescribed in patients

on peritoneal dialysis, especially when they have

paralytic ileus.

Author contributions

Concept or design: YH Wong, SSH Wong.

Acquisition of data: YH Wong, SM Li.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YH Wong, SM Li.

Drafting of the manuscript: YH Wong, SM Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YH Wong, SM Li.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YH Wong, SM Li.

Drafting of the manuscript: YH Wong, SM Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Ching-ki Fung and Dr Ngai-sheung Fung,

pathologists of United Christian Hospital, for the detailed

analysis of the colonic specimen and illustrative pathology

images.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient’s next-of-kin has granted permission for submission and publication of this case report.

References

1. Swanson BJ, Limketkai BN, Liu TC, et al. Sevelamer crystals in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT): a new entity associated with mucosal injury. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1686-93. Crossref

2. Yuste C, Mérida E, Hernández E, et al. Gastrointestinal complications induced by sevelamer crystals. Clin Kidney J 2017;10:539-44. Crossref

3. Uy PP, Vinsard DG, Hafeez S. Sevelamer-associated rectosigmoid ulcers in an end-stage renal disease patient.

ACG Case Rep J 2018;5:e83. Crossref

4. Nambiar S, Pillai UK, Devasahayam J, Oliver T, Karippot A. Colonic mucosal ulceration and gastrointestinal bleeding associated with sevelamer crystal deposition in a

patient with end stage renal disease. Case Rep Nephrol

2018;2018:4708068. Crossref

5. Tieu C, Moreira RK, Song LMWK, Majumder S, Papadakis KA, Hogan MC. A case report of sevelamer-associated

recto-sigmoid ulcers. BMC Gastroenterol

2016;16:20. Crossref

6. Magee J, Robles M, Dunaway P. Sevelamer-induced gastrointestinal injury presenting as gastroenteritis. Case

Rep Gastroenterol 2018;12:41-5. Crossref

7. Lai T, Frugoli A, Barrows B, Salehpour M. Sevelamer carbonate crystal–induced colitis. Case Rep Gastrointest

Med 2020;2020:4646732. Crossref