Purtscher-like retinopathy in a patient with lupus: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Purtscher-like retinopathy in a patient with lupus: a case report

Cynthia KL Cheng, MB, ChB1; Kenneth KH Lai, MB, ChB1; Andrew KT Kuk, MB, BS, MRCS1; Tracy HT Lai, FCOphthHK, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)2,3; Sarah T Wang, MB, BS, MRCS1; Simon TC Ko, FRCS (Edin), FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1

1 Department of Ophthalmology, Tung Wah Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Ophthalmology, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Cynthia KL Cheng (chengklc@yahoo.com)

Case report

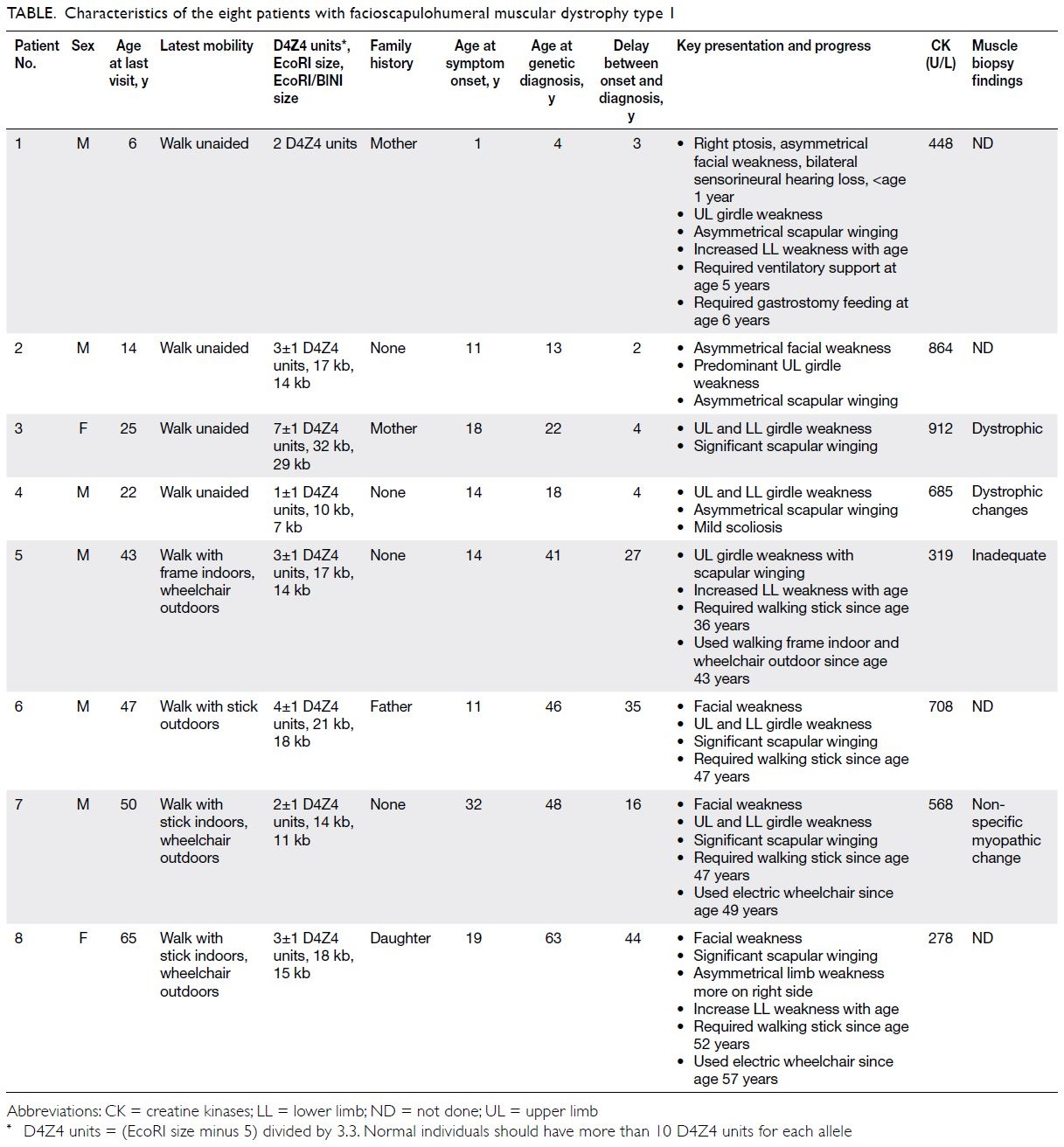

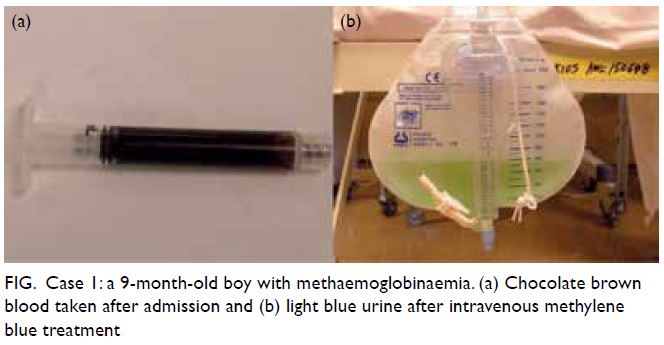

In January 2020, a 32-year-old Filipino woman was

admitted to the medical unit of our hospital with

subacute onset of a facial malar rash, digital vasculitis

purpura and alopecia. Systemic lupus erythematosus

(SLE) had been newly diagnosed according to the

Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics

criteria. Initial blood tests revealed an elevated

serum anti-ds DNA antibody level, positive anti-SM

antibody, low C3 and C4 as well as pancytopenia.

Fasting glucose and lipid profile were unremarkable.

She was first treated with oral hydroxychloroquine

200 mg daily and oral prednisolone 20 mg daily.

One week later, she presented to our ophthalmology

clinic with acute-onset painless blurring of vision in

her right eye upon waking that morning. Physical

examination revealed a best-corrected visual acuity

of finger counting at 30 cm in her right eye and 6/6

in her left eye with a right relative afferent pupillary

defect. Slit-lamp examination was unremarkable

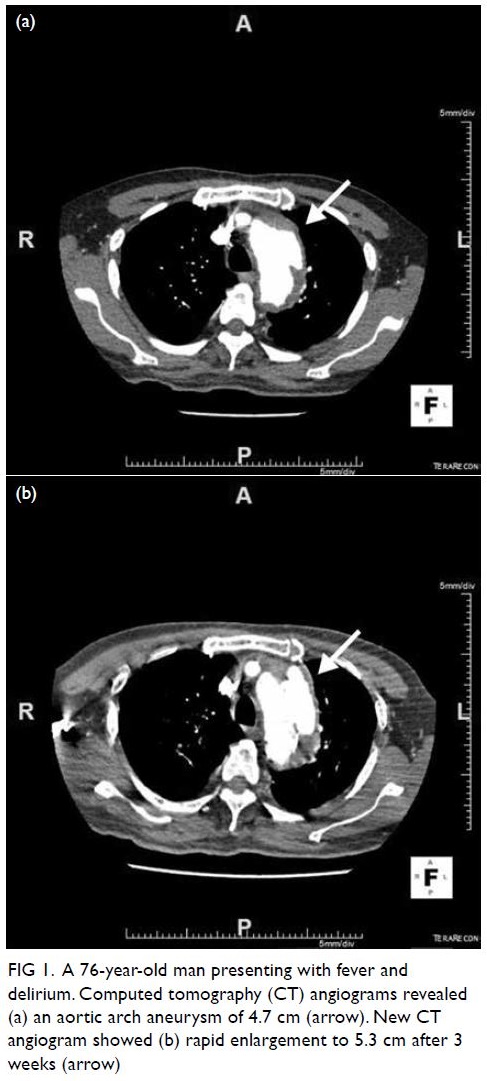

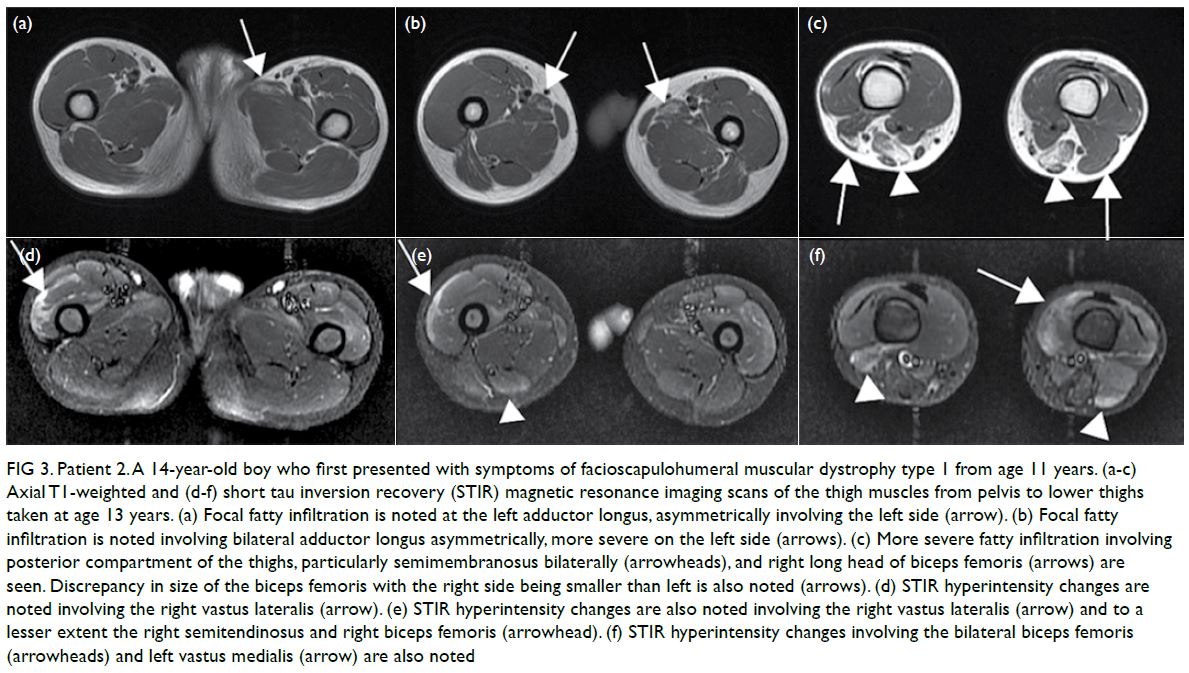

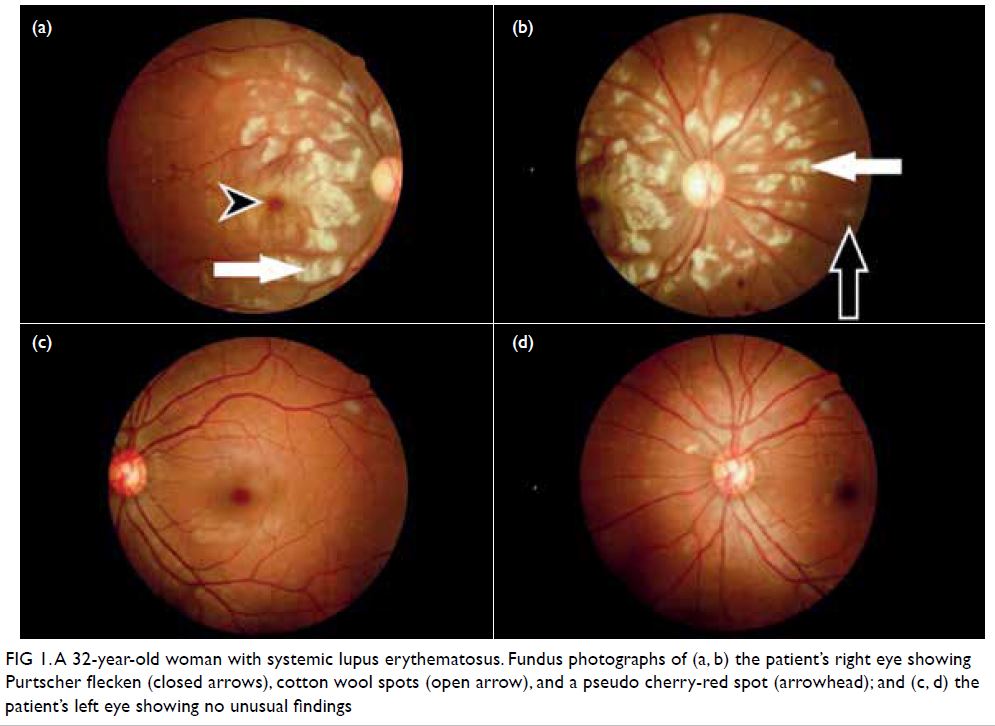

with no anterior chamber inflammation. Fundus

examination revealed numerous Purtscher flecken,

which are polygonal patches of retinal whitening

with distinct border and normal retina in between,

across the posterior pole. A pseudo cherry-red

spot and confluent retinal whitening could be seen

in the right eye secondary to proximal occlusion

of the retinal arteries. A few flame-shaped retinal

haemorrhages were observed inferior and temporal

to the optic disc in the right eye. The right optic disc

was mildly pale with sharp margins and the retinal

vessels were not tortuous, while the left optic disc is

pink (Fig 1).

Figure 1. A 32-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. Fundus photographs of (a, b) the patient’s right eye showing Purtscher flecken (closed arrows), cotton wool spots (open arrow), and a pseudo cherry-red spot (arrowhead); and (c, d) the patient’s left eye showing no unusual findings

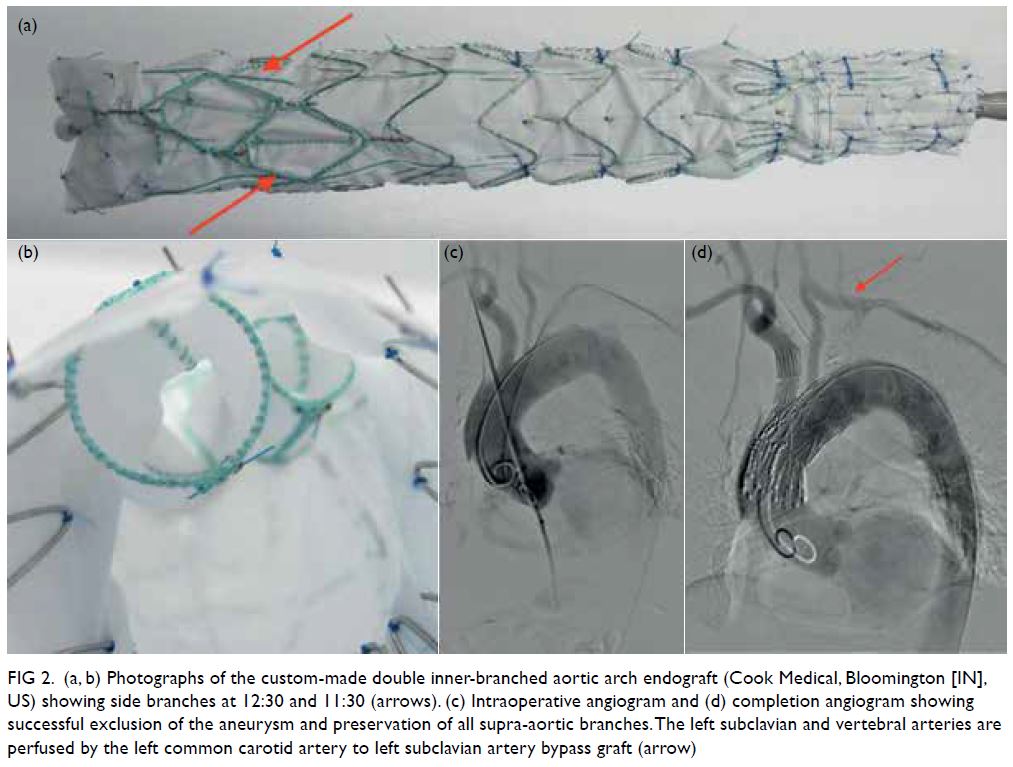

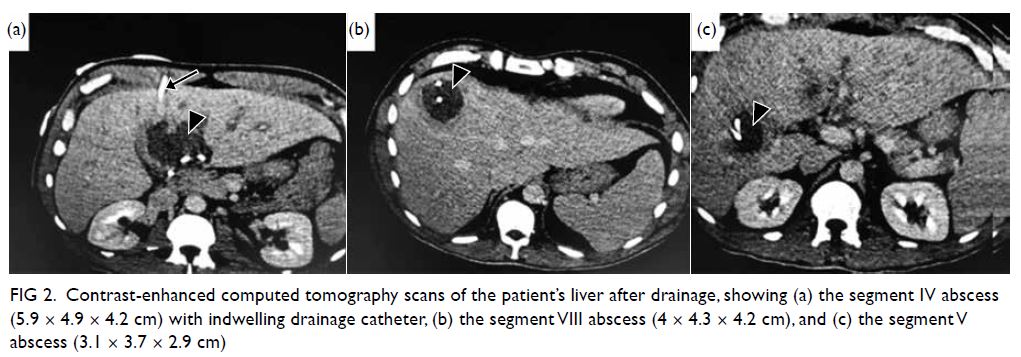

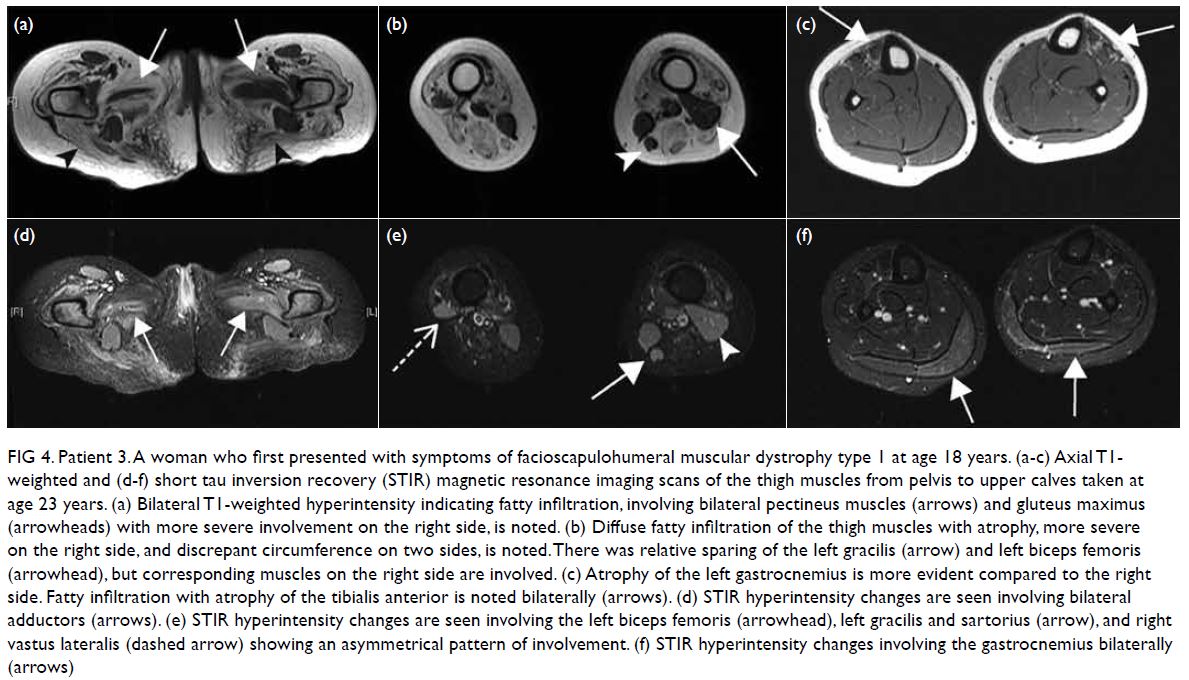

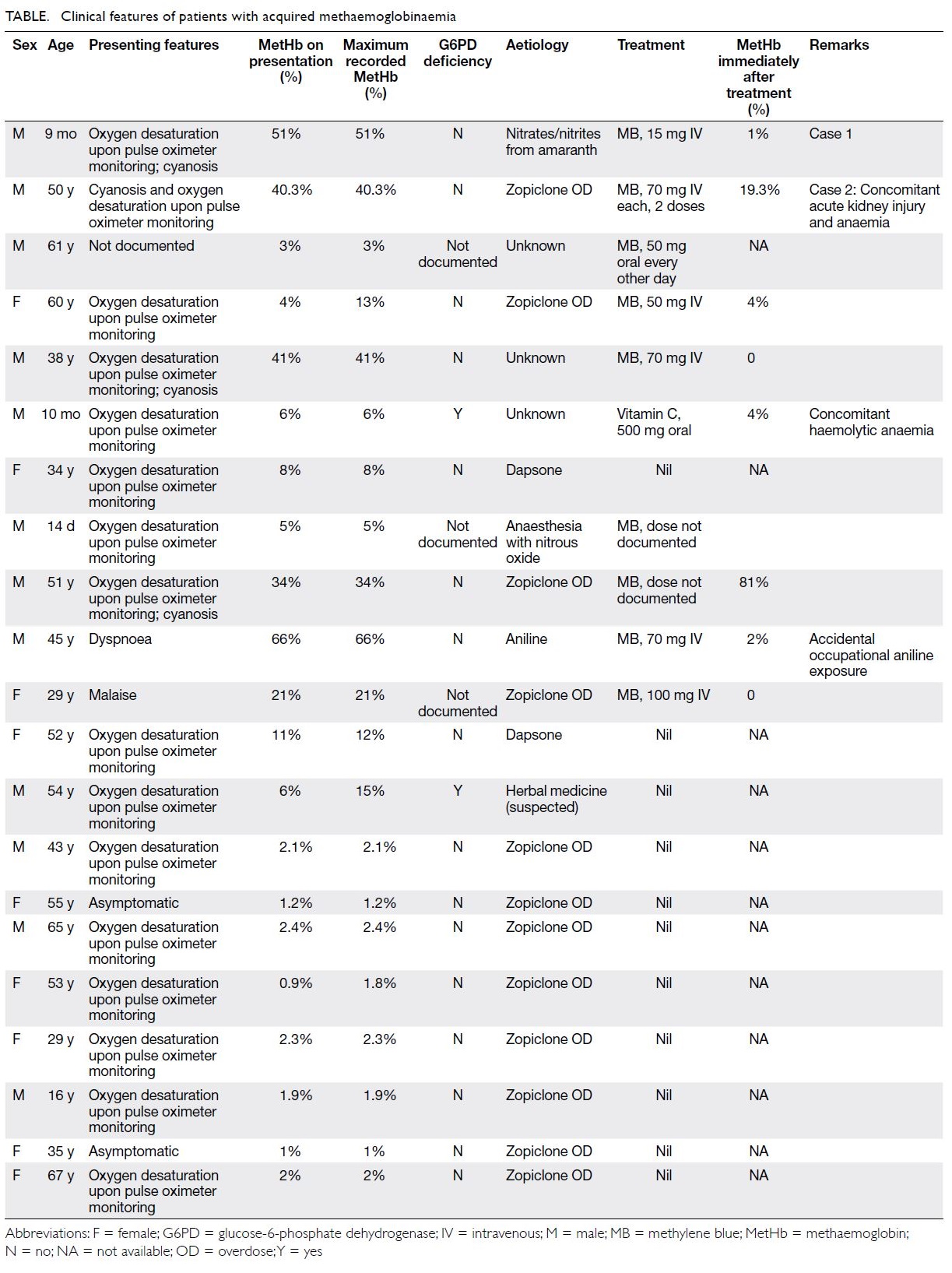

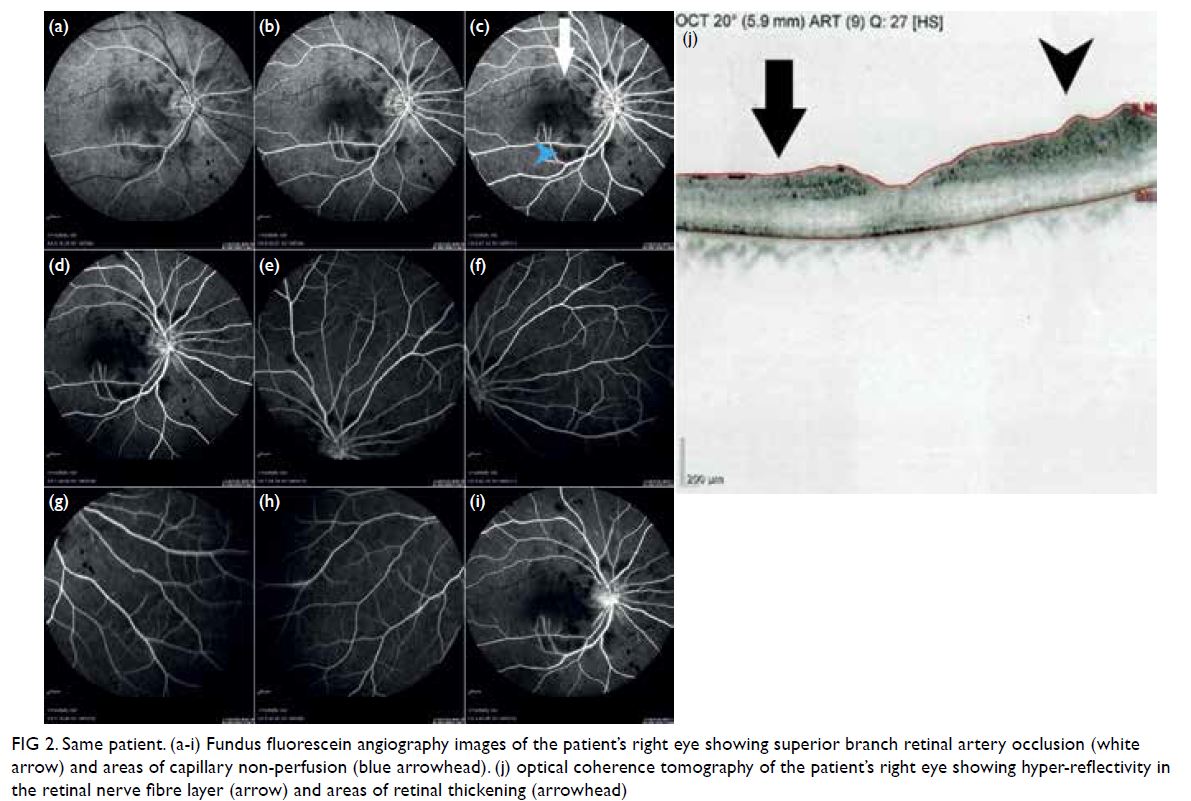

Urgent optical coherence tomography of the

right eye showed hyper-reflectivity in the retinal

nerve fibre layer and areas of retinal thickening.

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) of the

patient’s right eye showed capillary non-perfusion

corresponding to Purtscher flecken, superior branch

retinal arterial occlusion, and peripapillary staining

(Fig 2). Optical coherence tomography and FFA

of the patient’s left eye were normal. Given the typical fundus appearance and FFA findings, our

provisional diagnosis was Purtscher-like retinopathy

with branch retinal artery occlusion related to

SLE. We advised her medical team to escalate her

systemic treatment immediately and she was given

intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg daily for

3 days, followed by oral cyclophosphamide 500 mg

for 1 day before switching to oral prednisolone

40 mg daily. Oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily

was continued. On high-dose steroids, she developed

features of psychosis that subsequently resolved.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no

features typical of central nervous system lupus such

as ischaemia and vasculitis. We closely monitored

her condition and visual acuity had not improved

1 month after systemic treatment was started,

remaining at finger counting at 30 cm. Fundus

examination of the right eye after treatment revealed

macula oedema and pseudo cherry-red spot, with no

signs of optic atrophy. Cotton wool spots in the left

eye had resolved. The patient chose to seek further

medical attention overseas.

Figure 2. Same patient. (a-i) Fundus fluorescein angiography images of the patient’s right eye showing superior branch retinal artery occlusion (white arrow) and areas of capillary non-perfusion (blue arrowhead). (j) optical coherence tomography of the patient’s right eye showing hyper-reflectivity in the retinal nerve fibre layer (arrow) and areas of retinal thickening (arrowhead)

Discussion

At least one third of patients with SLE have

ophthalmological involvement. Retinal and choroidal

pathology are sinister ocular complications of SLE

that can lead to permanently impaired visual acuity.

Purtscher-like retinopathy is a type of vaso-occlusive

retinopathy associated with multiple conditions

including connective tissue disorders, pancreatic

disease, renal disease, and haematological disease.1

We report this rare case of Purtscher-like

retinopathy in a patient with SLE which had a

devastating visual outcome despite systemic

treatment. In an observational case series of

5688 patients with SLE, eight cases of Purtscher-like

retinopathy were diagnosed.1 All patients had

received treatment but most had optic atrophy

and persistent low visual acuity,1 consistent with

the outcome for our patient. Poor visual acuity has

also been attributed to presentation with a pseudo cherry-red spot. The prognosis of Purtscher-like

retinopathy is better in patients with other underlying

diseases. For example, Shahlaee et al2 reported a case

of postviral Purtscher-like retinopathy presenting

with finger count visual acuity in both eyes. No

treatment was given but the patient’s final visual

acuity improved to 20/20 with bilateral scotoma on

visual field assessment. Another case of Purtscher-like

retinopathy in a patient with adult-onset Still’s

Disease was reported by Yachoui,3 in which initial

visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/25 in

the left. Oral prednisolone 60 mg daily was initiated

and the patient’s final visual acuity was 20/25 in both

eyes with evidence of established bilateral optic

atrophy.

In a retrospective case control study, Gao et al4

reported a 0.66% prevalence of retinal vasculopathy

among SLE patients with signs ranging from cotton

wool spots, retinal vascular attenuation to retinal

haemorrhages. Lupus retinopathy can result in

severe complications such as neovascularisation,

macula oedema and retinal vessel occlusion resulting

in vision loss.4 It is known that patients with high

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Disease

Index score are at higher risk of Purtscher-like

retinopathy, central nervous system lupus1 and vaso-occlusive retinopathy, reflecting severe systemic

microangiopathy.1 4

Because patients with active lupus are at risk

of Purtscher-like retinopathy that can lead to severe

irreversible visual loss,1 it is important to raise

awareness in patients with active lupus and visual

symptoms. A high index of suspicion for retinopathy

is needed for those with very active disease and

prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is warranted in

the presence of visual symptoms. Despite escalation

of treatment after the onset of visual symptoms,

our patient’s vision did not recover. Early aggressive

treatment to control SLE disease activity is essential

to prevent this blinding complication.

References

1. Wu C, Dai R, Dong F, Wang Q. Purtscher-like retinopathy in systemic lupus erythematous. Am J Ophthalmol

2014;158:1335-1341.e1. Crossref

2. Shahlaee A, Sridhar J, Rahimy E, Shieh WS, Ho AC. Paracentral acute middle maculopathy associated with

post viral Purtshcer-like retinopathy. Retinal Cases Brief

Rep 2019;13:50-3. Crossref

3. Yachoui R. Purtscher-like retinopathy associated with adult-onset

still disease. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2018;12:379-81. Crossref

4. Gao N, Li MT, Li YH, et al. Retinal vasculopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematous. Lupus 2017;26:1182-9. Crossref