© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Extraosseous myeloma of liver mimicking

multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma where a

distinction has to be made: two case reports

HM Kwok, MB, BS, FRCR#; Eugene Sean Lo, MB, BS#; T Wong, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology); Heather HC Lee, MB, BS/BSC, FRCR; HT Chau, MB, BS; FH Ng, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology); WH Luk, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology); Johnny KF Ma, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

# Equal contribution

Corresponding author: Dr HM Kwok (khm778@ha.org.hk)

Case report

Case 1

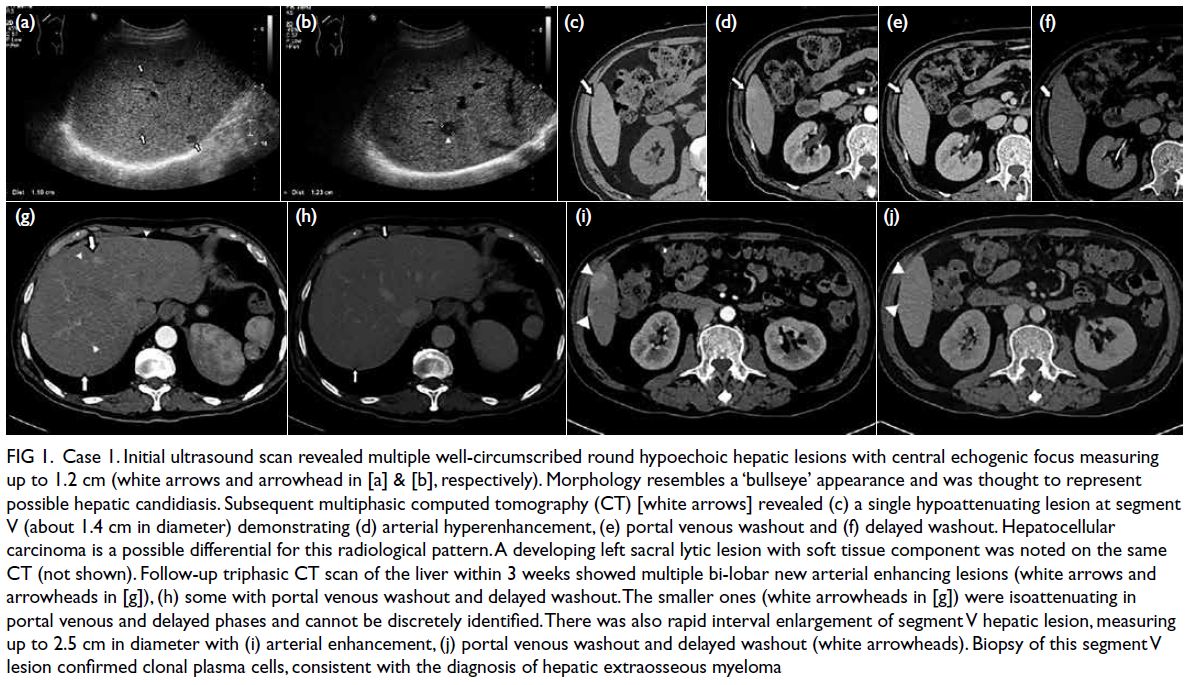

A 67-year-old man with kappa light chain multiple

myeloma (MM) had a baseline negative skeletal

survey and had undergone dual-tracer positron

emission tomography–computed tomography (CT)

with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose and carbon-11

acetate. An initial biochemical response to combined

chemotherapy with bortezomib, thalidomide

and dexamethasone later plateaued; therefore, he

was switched to second-line chemotherapy with

ixazomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone. He

then developed progressively deranged liver function and new-onset pancytopenia with fever during the

first cycle. Ultrasound revealed multiple bi-lobar

hepatic hypoechoic lesions, some with a central

echogenic focus surrounded by hypoechoic rim

(target appearance), suggesting possible hepatic

candidiasis. Nonetheless there was progressive

worsening of liver function and recurrent fever

despite intravenous antifungal therapy. Urgent

multiphasic CT revealed a small arterial enhancing

nodule in hepatic segment V with washout. A newly

developed lytic sacral lesion was suspected to be

myeloma involvement. The liver CT 3 weeks later

showed an interval increase in size and number of

these liver lesions with similar enhancement pattern. Multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was one

of the prime differential diagnoses (Fig 1). Hepatitis B

and C tests were negative. Tumour markers including

alpha-fetoprotein were normal. Due to the rapid

interval lesion enlargement, absence of risk factor for

HCC, and the need to exclude possible opportunistic

fungal infection, ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was

performed and confirmed myeloma involvement.

Figure 1. Case 1. Initial ultrasound scan revealed multiple well-circumscribed round hypoechoic hepatic lesions with central echogenic focus measuring up to 1.2 cm (white arrows and arrowhead in [a] & [b], respectively). Morphology resembles a ‘bullseye’ appearance and was thought to represent possible hepatic candidiasis. Subsequent multiphasic computed tomography (CT) [white arrows] revealed (c) a single hypoattenuating lesion at segment V (about 1.4 cm in diameter) demonstrating (d) arterial hyperenhancement, (e) portal venous washout and (f) delayed washout. Hepatocellular carcinoma is a possible differential for this radiological pattern. A developing left sacral lytic lesion with soft tissue component was noted on the same CT (not shown). Follow-up triphasic CT scan of the liver within 3 weeks showed multiple bi-lobar new arterial enhancing lesions (white arrows and arrowheads in [g]), (h) some with portal venous washout and delayed washout. The smaller ones (white arrowheads in [g]) were isoattenuating in portal venous and delayed phases and cannot be discretely identified. There was also rapid interval enlargement of segment V hepatic lesion, measuring up to 2.5 cm in diameter with (i) arterial enhancement, (j) portal venous washout and delayed washout (white arrowheads). Biopsy of this segment V lesion confirmed clonal plasma cells, consistent with the diagnosis of hepatic extraosseous myeloma

Case 2

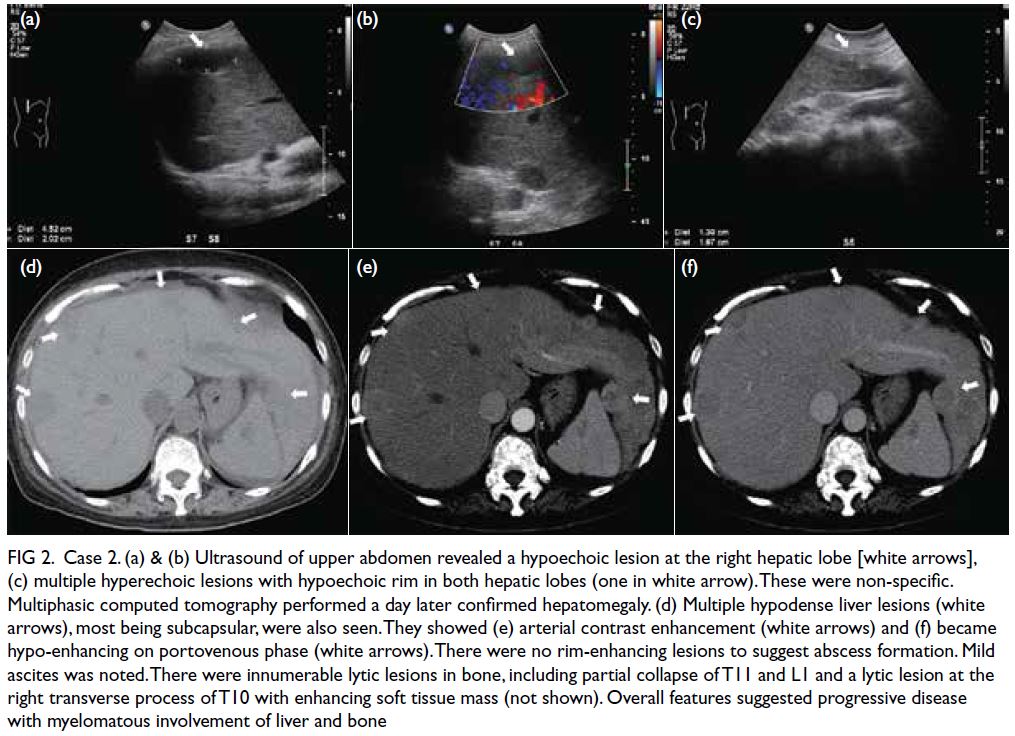

A 51-year-old woman with lambda light chain

MM diagnosed in 2011 was in remission following

treatment with bortezomib, thalidomide and

dexamethasone. Autologous peripheral blood

stem cell transplantation was performed but she

developed disease relapse 18 months later, salvaged

by combined bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone.

She presented within a year with a second relapse and

a 1-week history of fever, increasing diffuse bone pain

and abdominal distention. Mild hepatosplenomegaly

was noted on physical examination. Pancytopenia

was evident (haemoglobin 7.6 g/dL, platelet count

17×109/L, white blood cell count 1.7×109/L). Blood

culture and hepatitis markers were negative.

Ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic lesion at the

right hepatic lobe, bi-lobar hepatic hyperechoic lesions with hypoechoic rim and mild ascites.

In the presence of her high swinging fever, liver

abscesses were suspected. Hepatosplenomegaly was

confirmed on CT performed 1 day later. In addition,

multiple hypodense liver lesions, most of which were

subcapsular, were observed. They showed arterial

contrast enhancement and became hypo-enhancing

in the portovenous phase. No rim-enhancing lesions

were present to suggest abscess formation. There were

innumerable lytic lesions in bone, including partial

collapse of T11 and L1 and a lytic lesion at the right

transverse process of T10 with enhancing soft tissue

mass (Fig 2). Overall features suggested progressive

disease with presumably myelomatous involvement

of liver and bone. She was prescribed two cycles

of lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone

followed by four more cycles of lenalidomide and

dexamethasone. Follow-up CT showed interval

resolution of the previous noted bi-lobar liver

lesions and sub-centimetre hypo-enhancing focus

representing post-treatment change or residual

disease, supporting the presumption of liver

extraosseous myeloma (EM). Repeat bone marrow

examination revealed hypercellular marrow with

residual plasma cell myeloma. She then underwent

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Figure 2. Case 2. (a) & (b) Ultrasound of upper abdomen revealed a hypoechoic lesion at the right hepatic lobe [white arrows], (c) multiple hyperechoic lesions with hypoechoic rim in both hepatic lobes (one in white arrow). These were non-specific. Multiphasic computed tomography performed a day later confirmed hepatomegaly. (d) Multiple hypodense liver lesions (white arrows), most being subcapsular, were also seen. They showed (e) arterial contrast enhancement (white arrows) and (f) became hypo-enhancing on portovenous phase (white arrows). There were no rim-enhancing lesions to suggest abscess formation. Mild ascites was noted. There were innumerable lytic lesions in bone, including partial collapse of T11 and L1 and a lytic lesion at the right transverse process of T10 with enhancing soft tissue mass (not shown). Overall features suggested progressive disease with myelomatous involvement of liver and bone

Discussion

Extraosseous myeloma is an uncommon form of MM

associated with poorer prognosis and survival.1 2 It is

caused by migration of malignant plasma cells from

the bone marrow microenvironment. The presence of

extraosseous involvement of MM is not uncommon;

it has been previously reported in more than 63%

of patients in an autopsy series, with 28 to 30%

having liver involvement.1 The reticuloendothelial

system (liver, spleen and lymph nodes) is the most

commonly affected extraosseous site.2 Although well

documented in the pathology literature, this clinical

entity remains under-recognised and underreported

in radiology.

We report two cases of multifocal EM of

the liver in two Chinese patients from a tertiary

hospital in Hong Kong, mimicking multifocal HCC

on multiphasic CT. To the best of our knowledge,

this pattern has not been reported previously. First,

we aim to increase radiologist awareness of the

hypervascular multinodular pattern of liver EM.

Second, HCC is common in Southeast Asia including

Hong Kong and remains an imaging diagnosis with

no histological confirmation required prior to

treatment. There are overlapping imaging features

of both extraosseous MM in liver and HCC. Hence,

biopsy is needed for differentiation.

Imaging findings of EM are highly variable and

non-specific. The two most common presentations

are the more common diffuse form with hepatomegaly

in the absence of a focal lesion due to diffuse liver

parenchymal infiltration and the focal nodular form

with hypodense non-calcified nodule and minimal

enhancement. On ultrasound, focal patterns of

involvement can be hypoechoic, hyperechoic, mixed

or target (isoechoic nodule with hypoechoic rim).

On CT, focal lesions are generally described as

hypoattenuating with minimal enhancement and

no calcification. On magnetic resonance imaging,

focal lesions may be hyper- or hypo-intense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted

images with minimal gadolinium enhancement.2 3

Scarce literature has documented hypervascular

enhancement patterns with washout on multiphasic

CT or magnetic resonance imaging, and only few

case reports have reported only a solitary focal

mass.4 5 6 The multinodular form with hypervascular

enhancement pattern has not been reported before.

Currently there remains a lack of knowledge about

distinction of EM of liver from other hypervascular

liver tumours due to its rarity. Arterial phase imaging

is vital for lesion detection since some of the lesions

may be too small and too vaguely hypo-enhancing

to be detected during portovenous or delayed

phases. The differential diagnoses with multiple

hypervascular liver masses commonly include

multifocal HCC and hypervascular metastases. Its significance is underestimated, especially in areas

where HCC is endemic, such as Southeast Asia.

Clinicians and even radiologists may misdiagnose

these lesions as HCC, which is an imaging diagnosis,

and specific oncological treatment will be given

without histological confirmation of the lesion

leading to mismanagement. It is important to

bear in mind the possibility of myeloma of liver in

patients with known myeloma who present with

hypervascular mass on CT. We advocate a diagnostic

approach with emphasis on the use of multiphasic

cross-sectional studies including CT for detection,

and risk stratification (by alpha-foetal protein, and

hepatitis status). If these appear atypical of HCC or

EM involvement of liver, a timely biopsy to confirm

the diagnosis is recommended to avoid misdiagnosis

and subsequent mismanagement.

There are other points in the diagnostic

challenge posed by EM of the liver that influence

clinical management.

First, the variable sonographic appearance

of multinodular hepatic lesions, including target

appearance mimicking hepatic candidiasis, and

hypoechoic lesions raising a suspicion of pyogenic

abscesses, may lead to unnecessary antifungal or

antibacterial treatment.

Second, only one single large lesion was initially seen in our first case on multiphasic CT. This was

in concordance with multiple previous studies that

reported cases of EM of liver where lesions are more

conspicuous on ultrasound than on CT.3 Regarding

the hepatic lesions on CT from our cases, they were

most conspicuous on the arterial phase, while the

smaller ones may be isoattenuating or minimally

hypo-enhancing on portovenous or delayed phases.

In addition, most lesions had a subcapsular location

in the liver, an important area to review. Knowing that

this entity may be underdiagnosed, further studies are

needed to determine the most sensitive initial staging

modality to look for liver involvement. Based on our

cases, both ultrasound and multiphasic CT (including

arterial, portovenous, and 5-minute delayed) phases

play an important role in initial screening, subsequent

characterisation, and in guiding biopsy.

Conclusion

Extraosseous myeloma of the liver is a rare and under-recognised

entity associated with poorer prognosis

and survival. Imaging features are non-specific but

can mimic multifocal HCC on multiphase CT. We

advocate the use of multiphasic CT (including arterial

phase) for detection. The presence of hypervascular

liver masses in patients with known MM should alert

radiologists to this diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis

should be by tissue biopsy if there is a mismatch

between clinical risk factors and imaging, especially

in areas endemic for HCC.

Author contributions

Concept or design: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

Acquisition of data: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

Acquisition of data: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HM Kwok, ES Lo.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the haematology and oncology physicians of Princess Margaret Hospital,

Hong Kong, for their professional patient care and invaluable

contribution to the understanding of a novel disease.

Declaration

Case 1 of the study was accepted as oral presentation in the 19th Asian Oceanian Congress of Radiology 2021, Malaysia.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee [Ref No.: KW/EX-21-054 (157-19)]. Patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki, with informed consent provided for treatment,

procedures, and publication.

References

1. Oshima K, Kanda Y, Nannya Y, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings in 52 consecutively autopsied cases with multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol 2001;67:1-5. Crossref

2. Moulopoulos LA, Granfield CA, Dimopoulos MA, Kim EE, Alexanian R, Libshitz HI. Extraosseous multiple myeloma: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;161:1083-7. Crossref

3. Philips S, Menias C, Vikram R, Sunnapwar A, Prasad SR.

Abdominal manifestations of extraosseous myeloma:

cross-sectional imaging spectrum. J Comput Assist

Tomogr 2012;36:207-12. Crossref

4. Cho R, Myers DT, Onwubiko IN, Williams TR. Extraosseous

multiple myeloma: imaging spectrum in the abdomen and

pelvis. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021;46:1194-209. Crossref

5. Marcon M, Cereser L, Girometti R, Cataldi P, Volpetti S,

Bazzocchi M. Liver involvement by multiple myeloma

presenting as hypervascular focal lesions in a patient with

chronic hepatitis B infection. BJR Case Rep 2016;2:20150013. Crossref

6. Tan CH, Wang M, Fu WJ, Vikram R. Nodular

extramedullary multiple myeloma: hepatic involvement

presenting as hypervascular lesions on CT. Ann Acad Med

Singap 2011;40:329-31. Crossref