Frontal lobe epilepsy and hibernoma: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2025 Apr;31(2):159–61 | Epub 3 Apr 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Frontal lobe epilepsy and hibernoma: a case

report

Rongjun Zhang, M Med#; Zhigang Gong, PhD#; Wenbing Jiang, M Med

Department of Neurosurgery, Suzhou TCM Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, China

# Equal contribution

Corresponding author: Dr Rongjun Zhang (zhangrongjun2000@163.com)

Case presentation

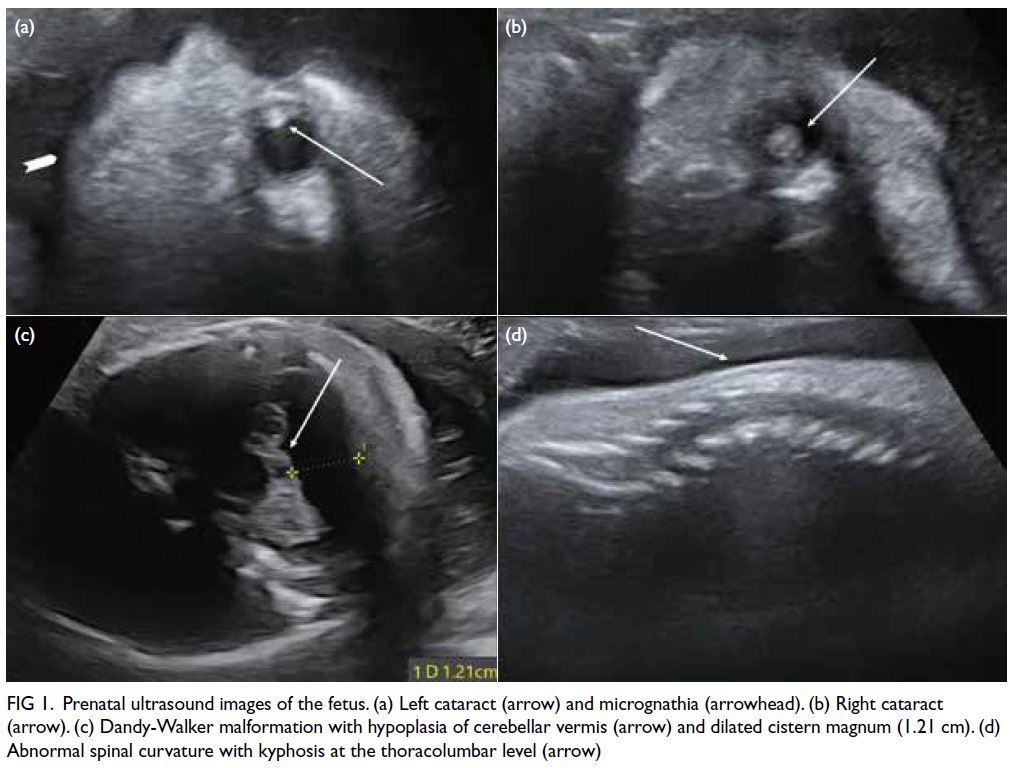

A 69-year-old female presented to the clinic

with a 2-year history of intermittent headaches.

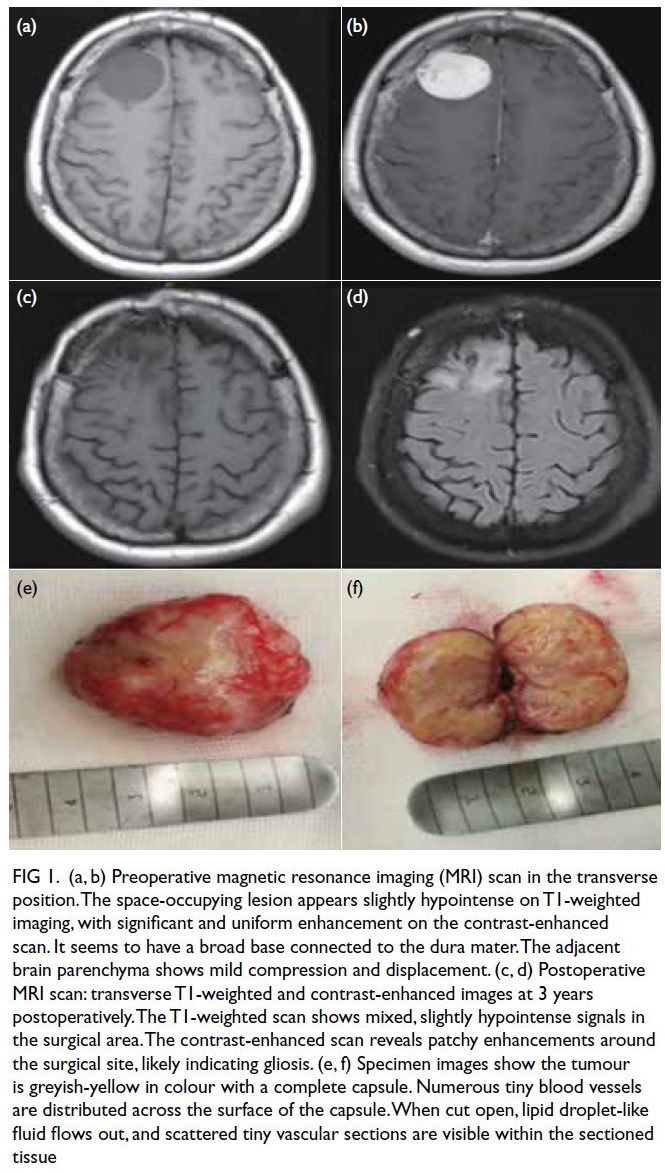

Cranial computed tomography (CT) and magnetic

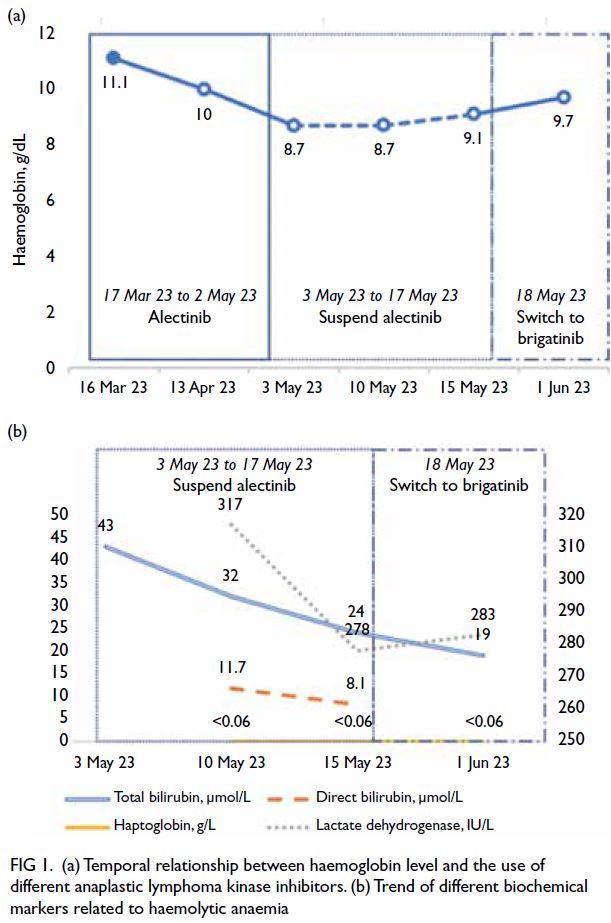

resonance imaging (MRI) examination (Fig 1a and b)

revealed a space-occupying lesion in the right frontal

lobe, suggestive of a meningioma. Preoperatively,

the patient experienced a single episode of epilepsy

lasting for 2 minutes, relieved by antiepileptic

medication.

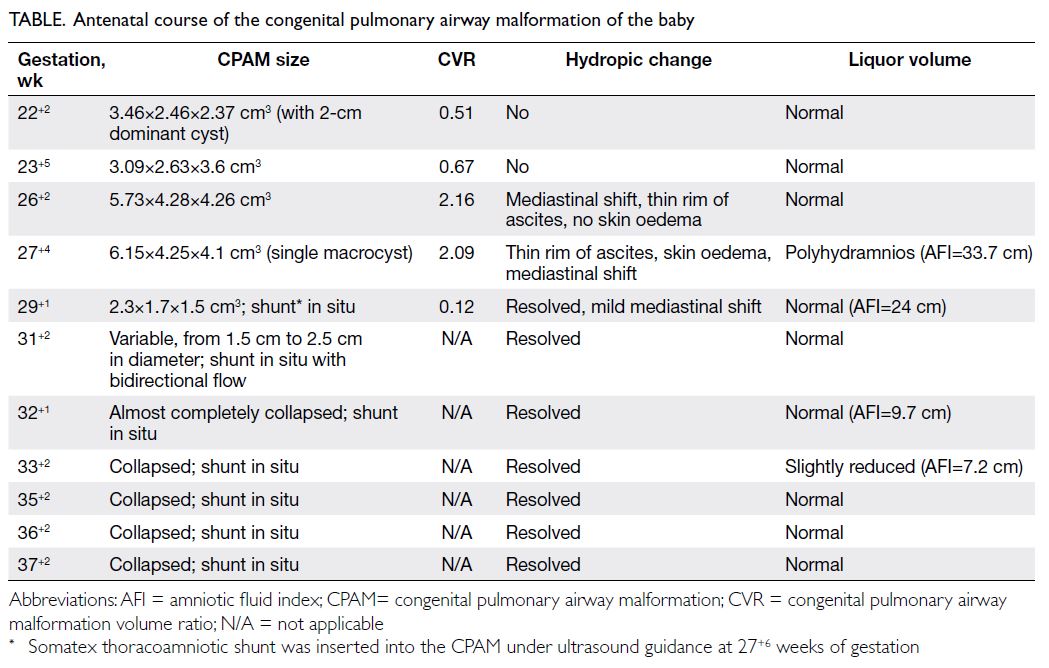

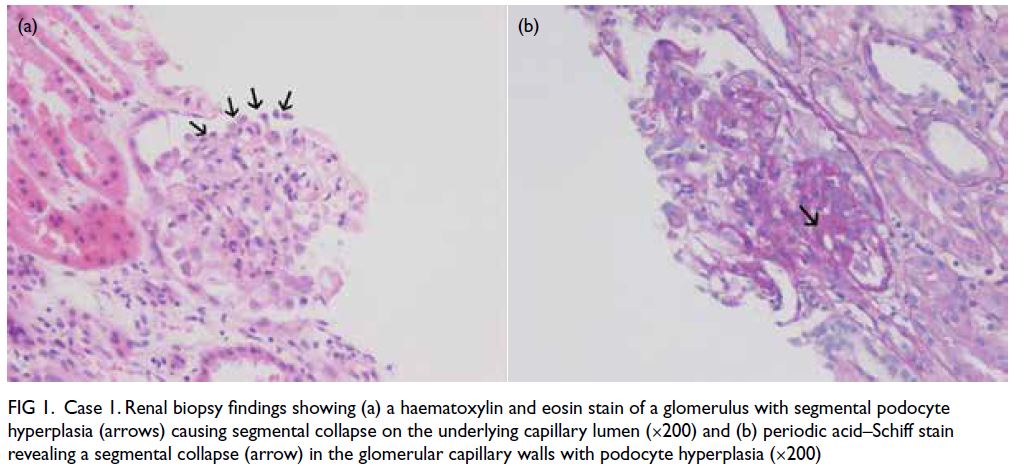

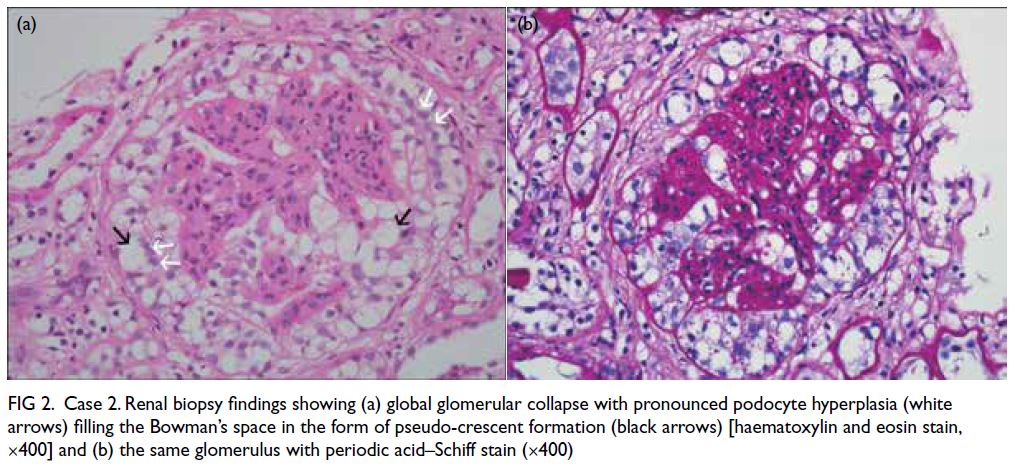

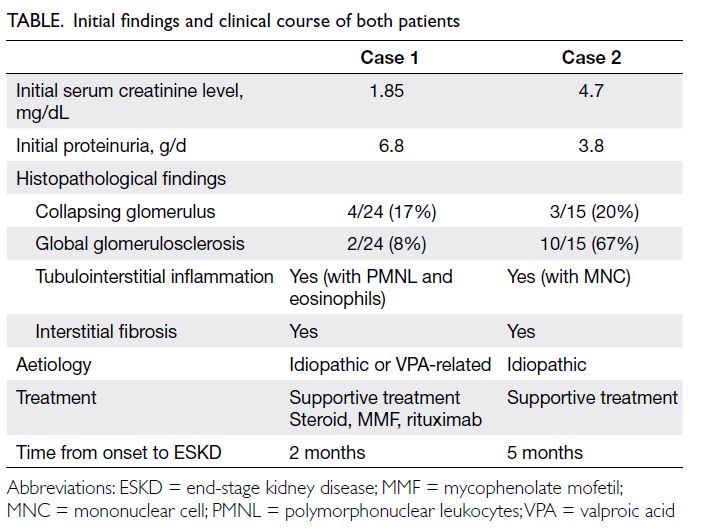

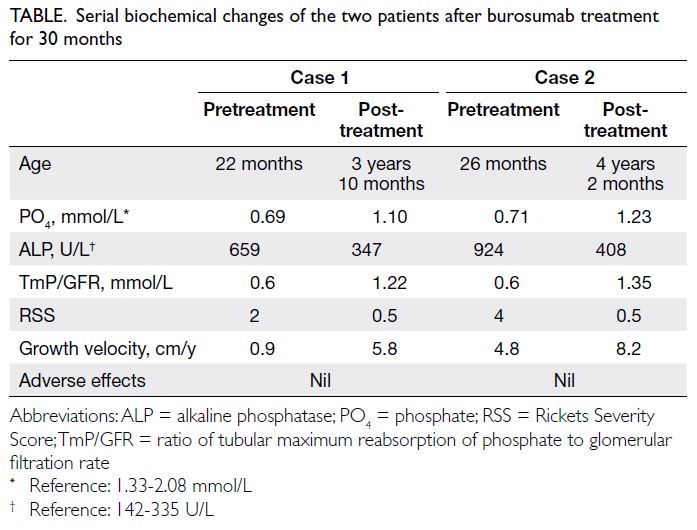

Figure 1. (a, b) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in the transverse position. The space-occupying lesion appears slightly hypointense on T1-weighted imaging, with significant and uniform enhancement on the contrast-enhanced scan. It seems to have a broad base connected to the dura mater. The adjacent brain parenchyma shows mild compression and displacement. (c, d) Postoperative MRI scan: transverse T1-weighted and contrast-enhanced images at 3 years postoperatively. The T1-weighted scan shows mixed, slightly hypointense signals in the surgical area. The contrast-enhanced scan reveals patchy enhancements around the surgical site, likely indicating gliosis. (e, f) Specimen images show the tumour is greyish-yellow in colour with a complete capsule. Numerous tiny blood vessels are distributed across the surface of the capsule. When cut open, lipid droplet-like fluid flows out, and scattered tiny vascular sections are visible within the sectioned tissue

Cranial surgery was performed based on

the preoperative CT localisation. The tumour was

completely separated and excised, measuring 4 × 3 × 2 cm3, greyish-yellow in colour, and encapsulated

(Fig 1e). The encapsulated surface was rich in blood

vessels. Upon opening, the tumour was yellow, and

lipid droplet-like fluid was observed on the surface

(Fig 1f).

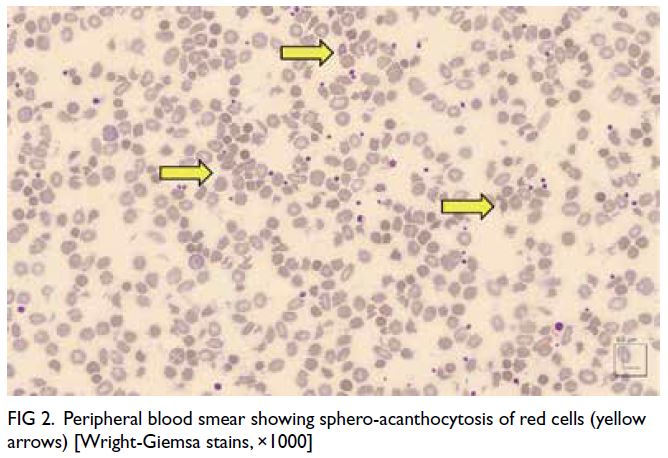

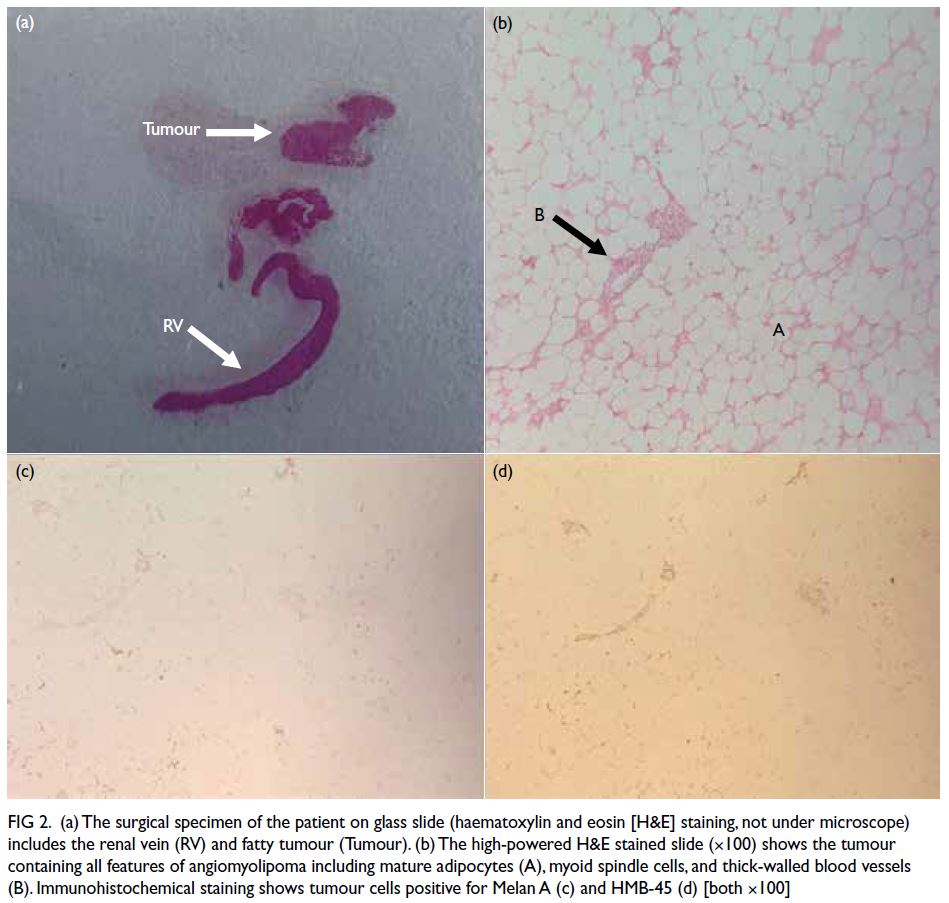

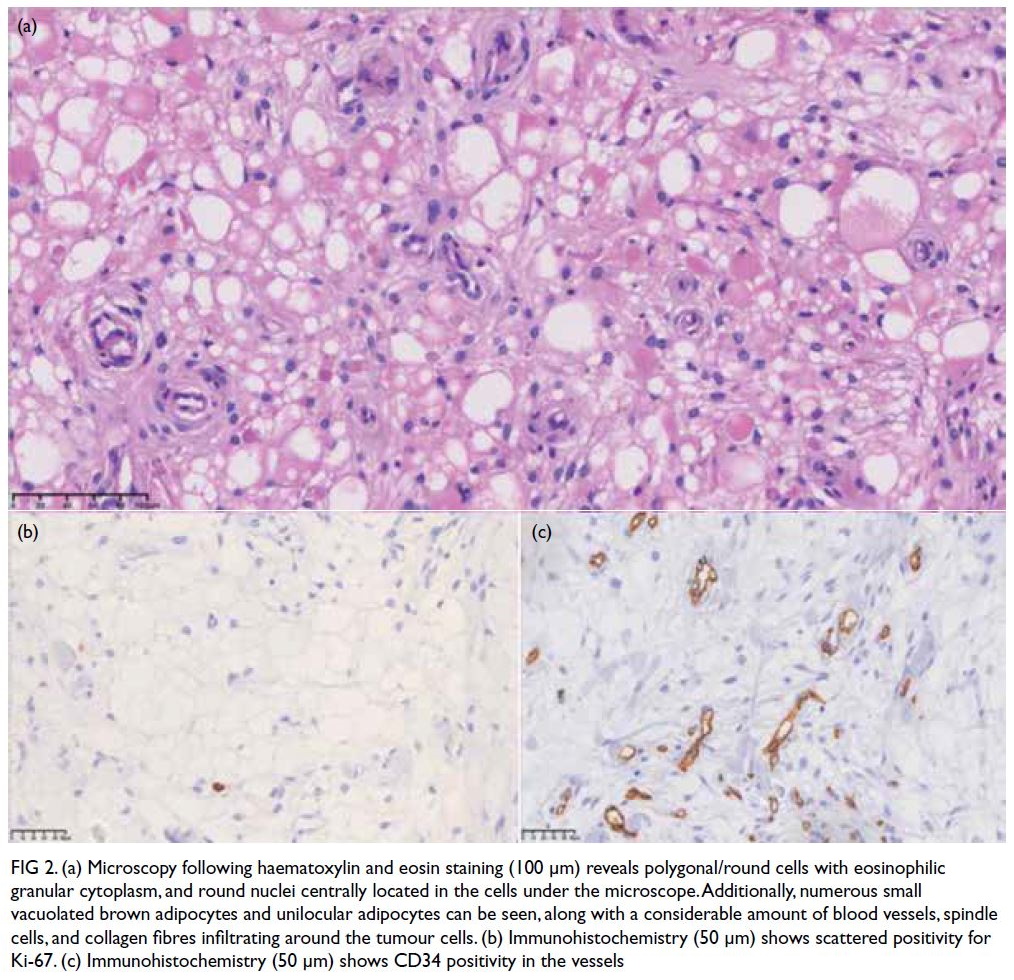

Postoperative pathology indicated a hibernoma.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a complete

thin capsule attached to the outside of the tumour

that was lobulated. A network of capillaries could

be seen inside. Under the microscope, polygonal/round cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm

were seen. The cell nuclei were round and centrally

located. In addition, many small vacuolated brown

adipocytes and unilocular adipocytes were seen,

with a considerable amount of blood vessels, spindle

cells, and collagen fibres infiltrating around the

tumour cells (Fig 2).

Figure 2. (a) Microscopy following haematoxylin and eosin staining (100 μm) reveals polygonal/round cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, and round nuclei centrally located in the cells under the microscope. Additionally, numerous small vacuolated brown adipocytes and unilocular adipocytes can be seen, along with a considerable amount of blood vessels, spindle cells, and collagen fibres infiltrating around the tumour cells. (b) Immunohistochemistry (50 μm) shows scattered positivity for Ki-67. (c) Immunohistochemistry (50 μm) shows CD34 positivity in the vessels

Immunohistochemistry showed CD34 to be

positive in the vessels, and Ki-67 scattered positive

with a proportion of <1%. Immunohistochemistry

results were as follows: CK (-), S-100 (-), MDM2 (-),

CDK4 (-), P53 (-), CD34 (vascular +), CD117 (-), and

Ki -67 (+, <1%) [Fig 2].

Postoperative re-examination confirmed

complete removal of the tumour, and the patient had

no further epileptic seizures. Three years later, cranial

MRI follow-up revealed no tumour recurrence (Fig 1c and d).

Discussion

Hibernomas are rare benign tumours composed of

brown adipose tissue.1 They are asymptomatic and slow-growing. Compared with lipomas originating

from white adipose tissue, hibernomas are

exceedingly rare, with <200 cases reported

in the literature.2 These tumours most commonly

occur in the proximal axial skeleton, where fetal

brown adipose tissue exists and continues into

adulthood. They are most frequently found in the

interscapular region, upper mediastinum, axilla,

retroperitoneum, and neck. According to literature

reports, hibernomas are extremely rare in the

cranial cavity. In 1972, Vagn-Hansen et al3 reported

a case of intracranial hibernoma. Due to medical

constraints at the time, detailed case descriptions of

CT and MRI images were not available. Therefore,

the diagnosis of this patient has significant clinical

significance and academic value. The rarity of

intracranial hibernomas in clinical diagnosis can

easily be overlooked or misdiagnosed as other more

common intracranial tumours such as meningiomas.

Clinicians and pathologists need to remain highly

vigilant for this rare tumour to ensure timely and

accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Imaging characteristics of hibernomas

In radiology, differentiation between hibernomas and

meningiomas is challenging. Hibernomas typically

present as low- to medium-intensity on T1-weighted

MRI and high intensity on T2-weighted MRI. Due

to their origin from adipose tissue, hibernomas

may show signal suppression in the fat-suppressed

sequence of MRI. Due to the rich vascular supply

inside the tumour, MRI post-contrast enhancement

is evident. Also, due to the high fat content of

hibernomas, they may appear as low density or iso-density

lesions on CT scans.

Meningiomas typically present as iso- to high-intensity

on both T1- and T2-weighted MRI and show

significant uniform enhancement following contrast

administration. Meningiomas often accompany the

dural tail sign, an important distinguishing feature in

imaging. Furthermore, the density of meningiomas

on CT scans is quite uniform, with significant

enhancement following contrast administration.

Therefore, while there is overlap in imaging between

hibernomas and meningiomas, detailed radiological

analysis, especially the combination of fat-suppressed sequences and tumour enhancement characteristics,

can help distinguish the two and increase diagnostic

accuracy.

Pathological characteristics of hibernomas

Pathological diagnosis is the gold standard for

confirming hibernomas. Histological features include

small multilocular brown adipocytes that have a rich

granular cytoplasm and central or eccentric round or oval nuclei. Unlike the single large lipid droplet in

white adipocytes, brown adipocytes contain multiple

small lipid droplets and abundant mitochondria,

giving the cytoplasm a granular appearance. In

addition, hibernomas usually have a rich vascular

network. Immunohistochemical staining showing

vascular CD34 positivity can further confirm the

diagnosis. Hibernoma cells have varying degrees of

S-100 protein and CD34 expression according to the

literature.4 5 Combining these pathological features

can effectively distinguish hibernomas from other

intracranial tumours such as meningiomas.

Conclusion

The diagnostic process of this case of intracranial

hibernoma emphasises the importance of clinicians

and pathologists when facing uncommon intracranial

tumours. Detailed imaging analysis and pathological

examination facilitate accurate differential diagnosis,

providing the best treatment plan for patients. More

case reports and research are needed to further

enrich the understanding and treatment strategies

of intracranial hibernomas.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, drafting of

the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Yanqing

Li and Dr Qinyi Wang from the Department of Pathology

at Suzhou TCM Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of

Chinese Medicine for their expertise and assistance in the

diagnosis and analysis of the patient’s condition.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Suzhou

TCM Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese

Medicine, China (Ref No.: 2024-005). The patient was treated in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient

provided written consent for publication of this case report.

References

1. Klevos G, Jose J, Pretell-Mazzini J, Conway S. Hibernoma.

Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:284-7.

2. Furlong MA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M. The

morphologic spectrum of hibernoma: a clinicopathologic

study of 170 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:809-14. Crossref

3. Vagn-Hansen PL, Osgård O. Intracranial hibernoma.

Report of a case. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A

1972;80:145-9. Crossref

4. Vassos N, Lell M, Hohenberger W, Croner RS, Agaimy A.

Deep-seated huge hibernoma of soft tissue: a rare differential diagnosis of atypical lipomatous tumor/well differentiated

liposarcoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013;6:2178-84.

5. Suster S, Fisher C. Immunoreactivity for the human

hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen (CD34) in

lipomatous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:195-200. Crossref