Neonatal haemoperitoneum due to splenic rupture: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2024 Jun;30(3):245–7 | Epub 6 Jun 2024

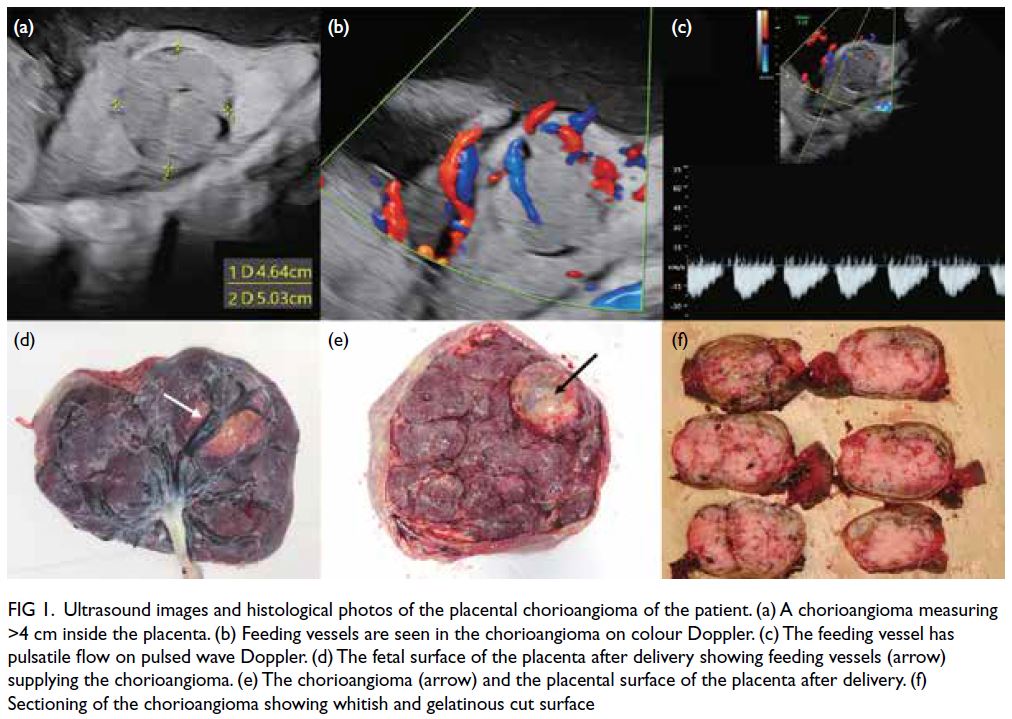

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Neonatal haemoperitoneum due to splenic rupture: a case report

Stephanie LH Cheung, MB, ChB, MRCS1,2; Bess SY Tsui, FRCSEd (Paed), FHKAM (Surgery)1,2; Rosanna MS Wong, FHKAM (Paediatrics)3; YH Tam, FRCSEd (Paed), FHKAM (Surgery)1,2

1 Department of Paediatric Surgery, Hong Kong Children's Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Paediatric Surgery and Paediatric Urology, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children's Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Stephanie LH Cheung (clh106@ha.org.hk)

Case presentation

Our female neonate presented in May 2023 was born full term at 39+4 weeks in a local private hospital with

a birth weight of 3.2 kg. There were no abnormalities

on antenatal check-up. She was born by vacuum-assisted

vaginal delivery due to non-reassuring

cardiotocography tracings. The Apgar score was

9 at 1 minute and 10 at 5 minutes of life. The first

24 hours postnatally was normal with meconium

passage and feeding initiated.

She was noted to have apnoea, pallor

and abdominal distension at 26 hours of life.

Haemoglobin level had dropped to 3 g/dL. Urgent

fluid boluses and packed cell transfusions were

given. Post-transfusion haemoglobin level was raised

to 10.3 g/dL. Her initial platelet counts were normal

but clotting profile was deranged (international

normalised ratio=1.49) and she was given fresh

frozen plasma transfusion. Clinically, the patient did

not require inotropic support. Urgent ultrasound

of the abdomen revealed ascites with echogenicity

suspicious of haemoperitoneum, with an echogenic

heterogeneous lesion over the left suprasplenic area

measuring 5 × 2 × 4 cm3 which was suspicious of a

haematoma. The spleen was not enlarged and the

liver and kidneys were normal. Elective intubation

and urgent transferral were arranged to the neonatal

intensive care unit for further management.

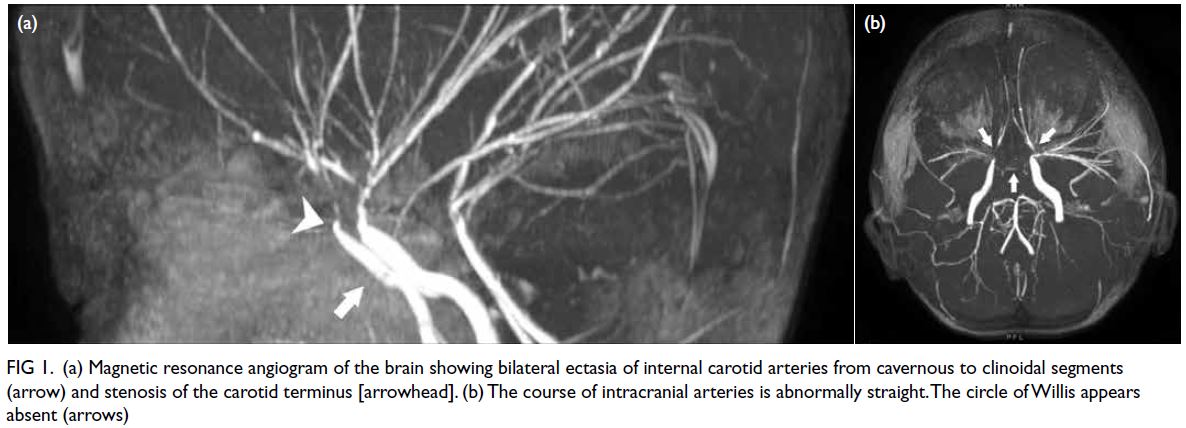

Upon arrival, the baby was noted to be pale

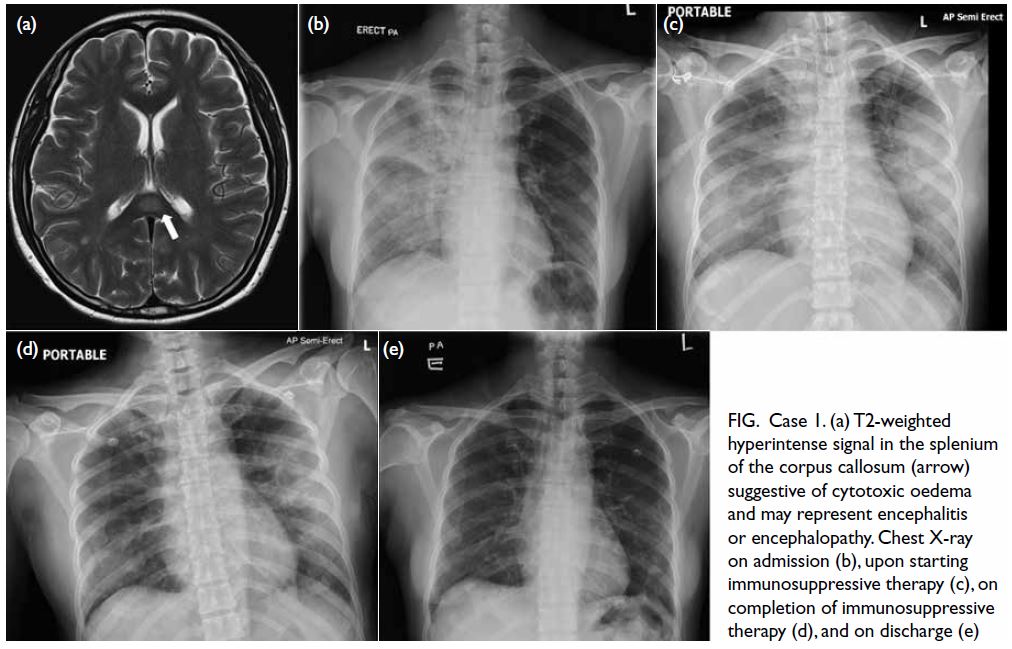

with gross abdominal distension (Fig 1). She was

tachycardic with pulse of 190 bpm and mean

arterial pressure of 40 mm Hg. She responded to

fluid resuscitation with a total of 180 mL of normal

saline boluses and packed cell transfusion and did

not require inotropic support. Haemoglobin level

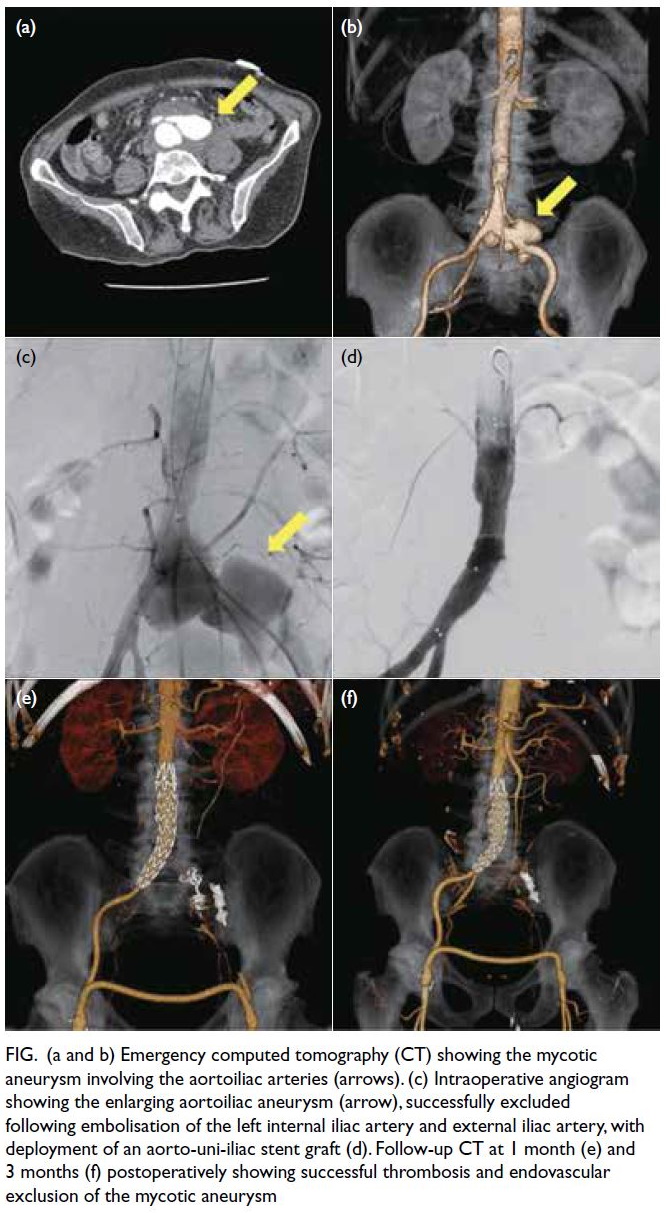

on arrival was 6 g/dL. Urgent computed tomography

of the abdomen was arranged which revealed

haemoperitoneum with a large left subphrenic

haematoma (6.3 × 3.6 × 6.9 cm3) likely arising from

the spleen. Contrast extravasation was noted over

the medial aspect of the spleen suggestive of active

bleeding. The size and enhancement of the spleen

was normal. The rest of the abdomen was normal.

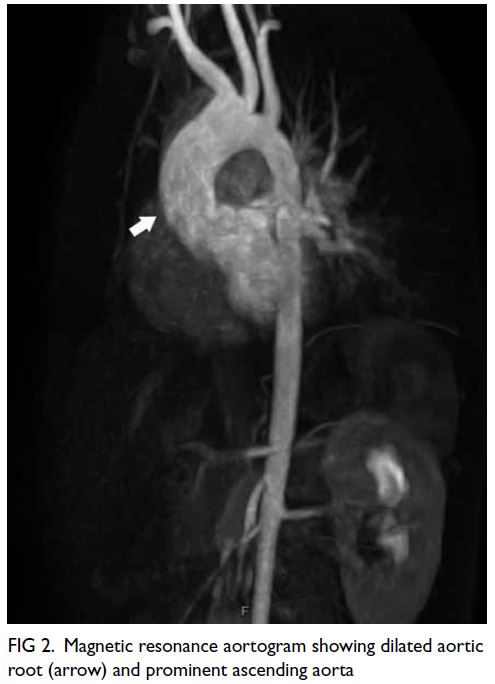

Urgent surgical exploration was performed in

view of active bleeding and haemodynamic instability of the patient despite resuscitation. Laparotomy

revealed large amount of old blood clots. The spleen

had a normal configuration and orientation and

was located over the left upper quadrant. A 1.5-cm

linear tear was noted over the medial side of the

lower pole of the spleen (Fig 2). Secure haemostasis

could not be achieved despite the use of packing,

oxidised regenerated cellulose and suturing, hence

splenectomy was performed. The short gastric

vessels were divided by cautery and splenic hilum

transfixed and over-sewn with 5-0 polydioxanone

sutures (Ethicon, Cincinnati [OH], United States). A

small spleniculi was noted and it was left untouched. The surgery lasted for 1 hour 34 minutes and total

blood loss including the drained old blood was 750 mL.

Postoperative recovery was unremarkable. Her

haemoglobin level stabilised on postoperative day

1, extubated on postoperative day 4, and full enteral

feeding achieved on postoperative day 7. She was

discharged on day 8 after receiving necessary post-splenectomy

vaccinations.

Discussion

Splenic rupture in newborns is a rare disease entity.

There were more mortality cases than survival in

literature. A review of literature from 1970 revealed

37 cases of splenic rupture in a neonate reported in

literature.1 This rupture is usually associated with

traumatic birth or other intrinsic pathology of the

parenchyma such as haemophilia or erythroblastosis

fetalis.2 However, there were also >10 cases of

spontaneous splenic rupture with no preceding risks

or predisposing factors in literature. Splenic injury

usually occurs in two stages, first with subcapsular

haematoma formation and then with urgent

symptoms presenting when the splenic capsule

gives way resulting in haemoperitoneum. The signs

and symptoms of haemoperitoneum are vague and

often easily missed. The common symptoms are

blood loss causing pallor, abdominal distension and

radiological evidence of intraperitoneal effusion

without pneumoperitoneum,3 which resembled our index case. Rarely, haemoperitoneum can also

present with scrotal swelling or haematoma. Splenic

rupture usually occurs within the first day of life

but rarely can present as late as 5 days of life. The

initial haemoglobin level in these neonates is often

very low (<6 g/dL) and require immediately blood

transfusion support.

Due to the friable nature of splenic tissue in

a neonate, more than half of the cases described

in literature proceeded to splenectomy, like our

index case. Ten cases settled with conservative

treatment with transfusion of blood products, but

these cases usually present later (>10 hours of life)

and the neonates had stable haemodynamics. There

were cases where laparotomy was performed and

haemostasis was secured without splenectomy.1 Other methods for haemostasis were employed. In

a case report in 1976 where the spleen was almost

transacted at its lower pole, the laceration was

repaired by chromic catgut mattress sutures and

the patient survived.4 The second case used an

absorbable mesh for haemostasis.5 The third case

reported was in 2002, where the splenic capsule

ruptured with oozing and gel-foam and oxidised

regenerated cellulose was used to pack the spleen.2

Second-look laparotomy was performed 48 hours

later which revealed that the bleeding had stopped

after removal of packing materials. One case in

literature utilised interventional radiology for

splenic artery embolisation to stop the bleeding.3

The choice of conservative versus surgical versus

interventional radiological treatment depends on

the haemodynamic of the patient and availability of

expertise and material. Due to the rare nature of the

condition, no evidence reported superiority of one

treatment method over another.

Conclusion

Neonatal splenic rupture is a rare emergency with high mortality. High index of clinical suspicion and

early establishment of diagnosis is necessary for

timely treatment. Our patient presented classically

with a difficult delivery and typical presentation

of abdominal distension, pallor and hypovolaemic

shock. Splenectomy is still the mainstay of treatment

but other approaches are also feasible.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, acquisition

of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the

manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The parents of the patient provided written consent for publication of this case report.

References

1. Hui CM, Tsui KY. Splenic rupture in a newborn. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:E3. Crossref

2. Matsuyama S, Suzuki N, Nagamachi Y. Rupture of the spleen in the newborn: treatment without splenectomy. J Pediatr Surg 1976;11:115-6. Crossref

3. Raats JW, van Dam L, van Doormaal PJ, van Hengel-Jacobs M,

Langeveld-Benders H. Neonatal rupture of the spleen:

successful treatment with splenic artery embolization. AJR

Rep 2021;11:e58-60. Crossref

4. Chang HP, Fu RH, Lin JJ, Chiang MC. Prognostic factors and clinical features of neonatal splenic rupture/hemorrhage: two cases reports and literature review. Front

Pediatr 2021;9:616247. Crossref

5. Fasoli L, Bettili G, Bianchi S, Dal Moro A, Ottolenghi A.

Spleen rupture in the newborn: conservative surgical

treatment using absorbable mesh. J Trauma 1998;45:642-3. Crossref