Bacteriology and risk factors associated with periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty: retrospective study of 2543 cases

Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:Epub 29 Mar 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176885

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Bacteriology and risk factors associated with

periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty:

retrospective study of 2543 cases

KT Siu1; FY Ng2; PK Chan1;

Henry CH Fu1; CH Yan3; KY Chiu3

1 Department of Orthopaedics and

Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Private practice, Hong Kong

3 Department of Orthopaedics and

Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof KY Chiu (pkychiu@hkucc.hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Periprosthetic

joint infection after total knee arthroplasty is a serious complication.

This study aimed to identify risk factors and bacteriological features

associated with periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee

arthroplasty performed at a teaching hospital.

Methods: We reviewed 2543

elective primary total knee arthroplasties performed at our institution

from 1993 to 2013. Data were collected from the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority’s Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System, the Infection

Control Team, and the joint replacement division registry. The

association between potential risk factors and periprosthetic joint

infection was examined by univariable analysis and multivariable

logistic regression. Univariable analyses were also performed to examine

the association between potential risk factors and bacteriology and

between potential risk factors, including bacteriology, and early-onset

infection.

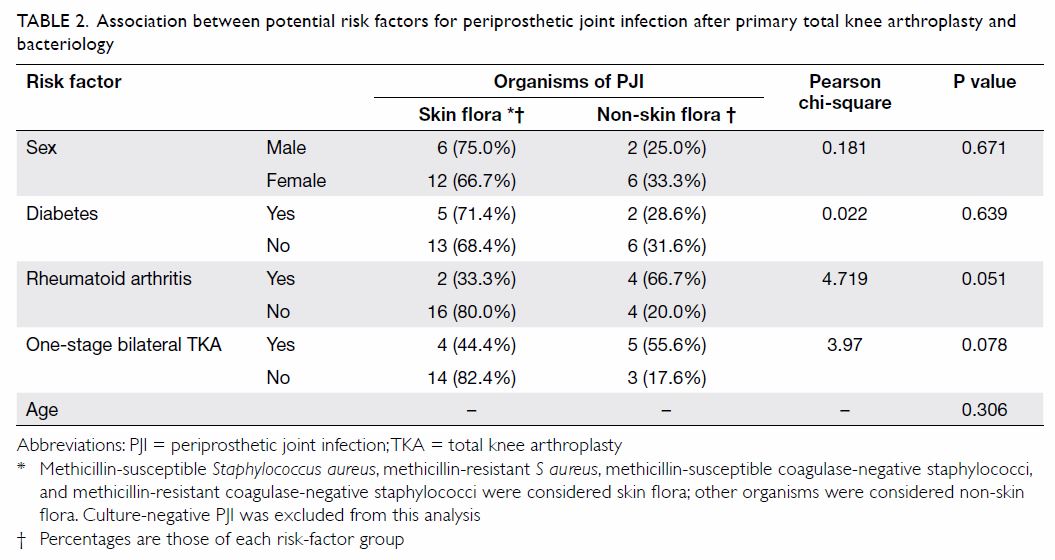

Results: The incidence of

periprosthetic joint infection in our series was 1.34% (n=34). The

incidence of early-onset infection was 0.39% (n=24). Of the

periprosthetic joint infections, 29.4% were early-onset infections. In

both univariable and multivariable analyses, only rheumatoid arthritis

was a significant predictor of periprosthetic joint infection.

Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus was the most common

causative organism. We did not identify any significant association

between potential risk factors and bacteriology. Periprosthetic joint

infection caused by skin flora was positively associated with

early-onset infection but the association was not statistically

significant.

Conclusion: The incidence of

periprosthetic joint infection after elective primary total knee

arthroplasty performed at our institution from 1993 to 2013 was 1.34%.

Rheumatoid arthritis was a significant risk factor for periprosthetic

joint infection.

New knowledge added by this study

- The incidence of periprosthetic joint infection after elective primary total knee arthroplasty performed at our institution from 1993 to 2013 was 1.34%.

- Rheumatoid arthritis was the only significant risk factor identified in the series.

- Early-onset infection may be associated with infection with skin flora. Therefore, in early-onset periprosthetic joint infection with negative cultures, an empirical antibiotic regimen should preferably provide adequate coverage against skin flora organisms.

Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is an uncommon

but serious complication after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Treatment is

often challenging and has a major impact on the patient. Multiple

operations are often required and patients may suffer from a long period

of disability. Moreover, PJI incurs considerable health care costs.1 2 3 Therefore, multiple strategies including antibiotic

prophylaxis, body exhaust systems, and laminar airflow systems have been

developed to reduce the incidence of PJI. Studies have also identified

modifiable risk factors for PJI after elective total joint replacement,4 5

6 7

8 9

10 11

12 13

14 with the aim of further

reducing the incidence of PJI. However, local data on the risk factors and

bacteriological features associated with PJI are still lacking.

This study had several aims. First, it aimed to

provide the most up-to-date local data on incidence of and risk factors

for PJI, including age, sex, presence of diabetes, presence of rheumatoid

arthritis, and one-stage bilateral TKA. Second, this study aimed to

provide an update on the bacteriology of PJI after elective primary TKA

and to examine the association between potential risk factors and

bacteriology. Third, we attempted to determine which risk factors,

including bacteriology, were more likely to be associated with early-onset

infection after elective primary TKA.

It is hoped that risk factors can be optimised or

modified to prevent infection after TKA. Furthermore, an improved

understanding of local bacteriological patterns and their relationship

with various risk factors can help guide antimicrobial therapy.

Methods

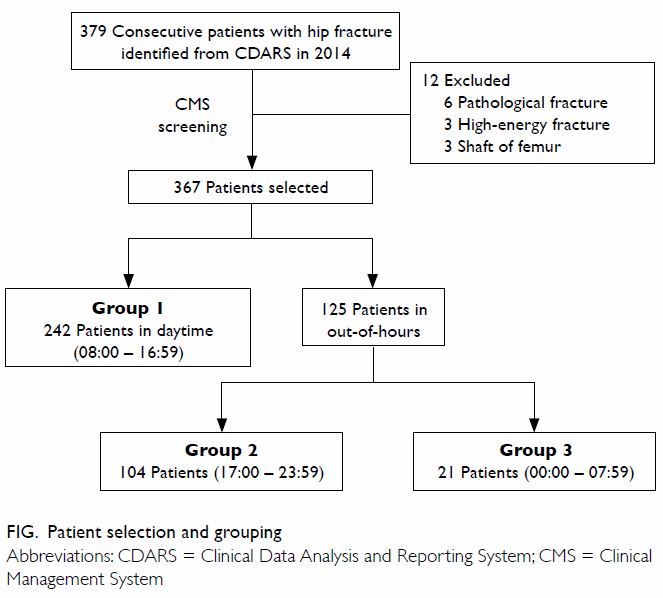

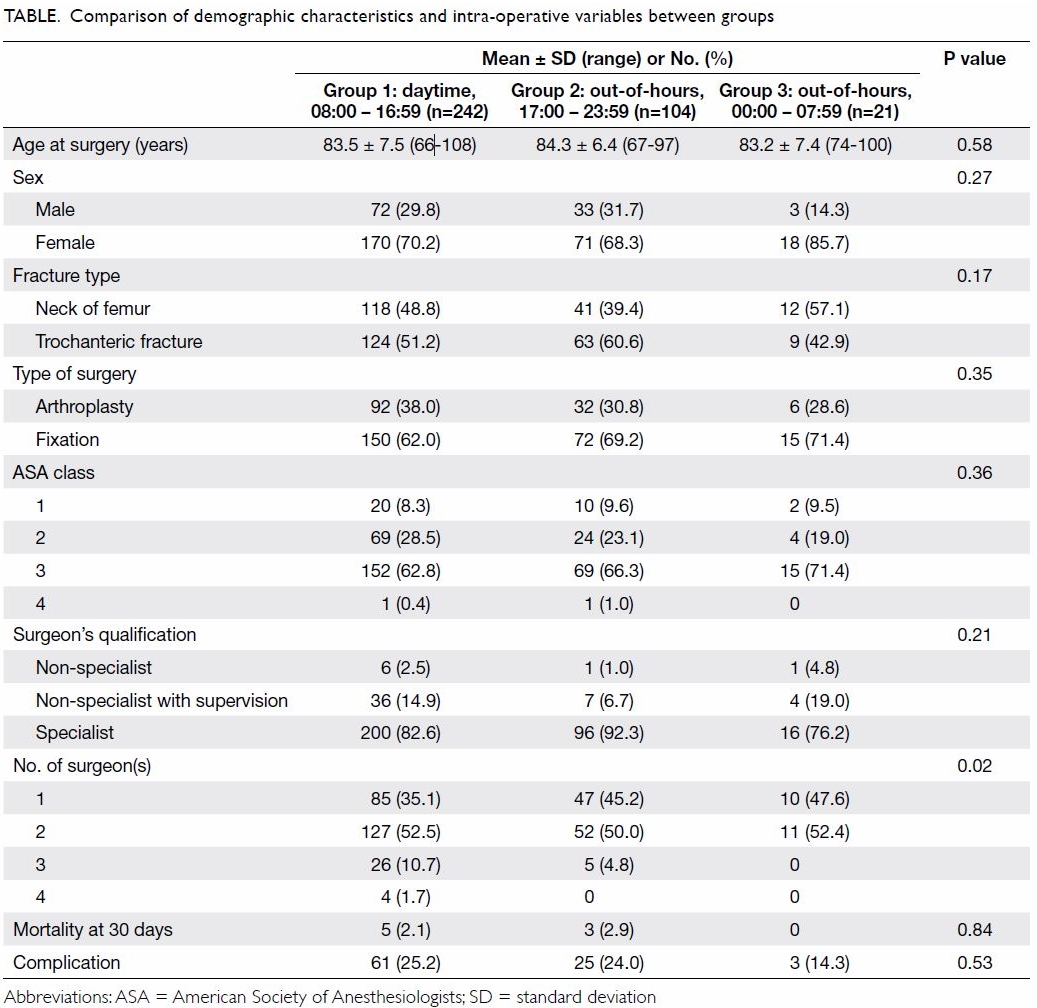

We reviewed 2543 elective primary TKAs performed at

the Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, from 1993 to 2013. Data were collected

by an infection control nurse of the Department of Microbiology who was

blinded to the study objectives. The cohort data were collected from the

Hong Kong Hospital Authority’s Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting

System, the Infection Control Team, and the hospital’s joint replacement

division registry. The keywords used in the data search were

‘periprosthetic joint infection’, ‘total knee arthroplasty’, and ‘surgical

site infection’. Revision arthroplasties and knee arthroplasties for

malignant conditions were excluded from the study. In patients with a

history of native joint infection, elective primary TKA was performed only

after eradication of the infection. Patients with active bacteraemia were

also precluded from elective primary TKA until they were infection-free.

There were no cases of severe immunosuppression. In relation to infection

control, the majority of perioperative protocols for primary TKA were the

same throughout the study period. Preoperatively, intravenous antibiotic

prophylaxis (1 g of cefazolin) was given within 1 h before skin incision.

In patients with penicillin allergy, other antibiotics were prescribed as

appropriate. Intra-operatively, laminar airflow and body exhaust systems

were used. There was no routine use of antibiotic-loaded cement or

postoperative antibiotics. Postoperative wound management was the same

throughout the study period.

Cohort characteristics, occurrence of PJI, and

bacteriological data were retrieved. Bacterial type was defined as

infection with skin flora or non-skin flora. Skin flora included

methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA),

methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), methicillin-susceptible

coagulase-negative staphylococci (MSCNS), and methicillin-resistant

coagulase-negative staphylococci (MRCNS). Other organisms were considered

non-skin flora.

The following potential risk factors for PJI were

analysed: age, sex, presence of diabetes, presence of rheumatoid

arthritis, and one-stage bilateral TKA. They were examined by univariable

analyses and then multivariable logistic regression to identify potential

predictors of PJI, while controlling for confounders. We also studied the

association of those potential risk factors with bacteriology and with the

timing of infection onset; culture-negative PJI was excluded from these

analyses. According to a working party convened by the Musculoskeletal

Infection Society in 2014,15 PJI

that occurs within 90 days of the index operation is considered

early-onset infection, whereas PJI that occurs later is considered

late-onset infection.

Both univariable and multivariable logistic

regression in this study used the simultaneous entry method, with

covariates of age (as a continuous variable) and sex, diabetes, rheumatoid

arthritis, and one-stage bilateral TKA (as dichotomous variables).

Outcomes are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals

(CIs). The regression model and data fitting were assessed using the

Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and diabetes and one-stage bilateral

TKA were excluded from the final model because of poor goodness-of-fit.

For associations between potential risk factors and bacteriology and

between potential risk factors and early onset of infection, only

univariable analyses were used owing to small numbers of events.

Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test, whereas age

was compared with the independent t test (two-tailed).

Significance was assumed if P<0.05. All statistical analyses were

conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk [NY], United

States). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles

outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

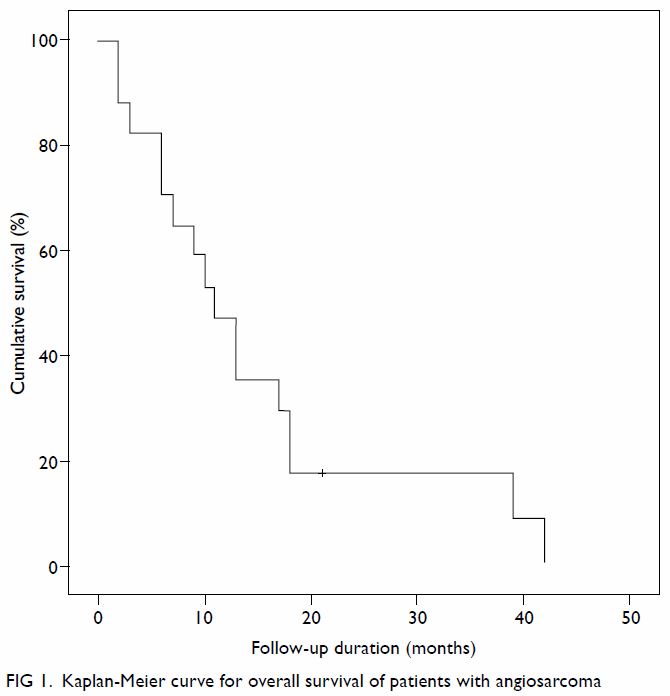

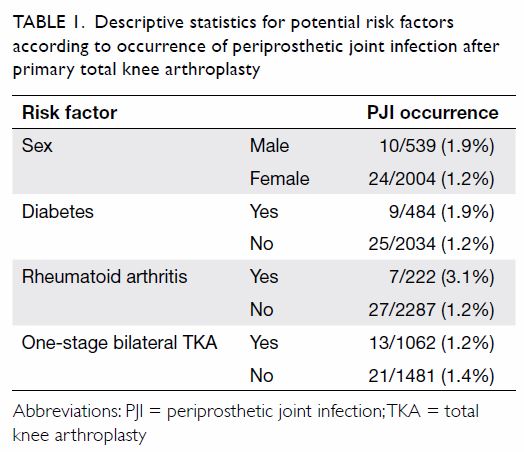

The incidence of PJI in our series was 1.34%

(n=34). The incidence of early-onset infection was 0.39% (n=10) and that

of late-onset infection was 0.94% (n=24). Among the cases PJI, 29.4% were

early-onset infection. Early-onset infection occurred within a median of

17 days after arthroplasty (interquartile range, 9-32 days). Late-onset

infection occurred within a median of 1 year and 8 months after

arthroplasty (interquartile range, 7 months to 2 years and 11 months).

Fifty-nine percent of infections occurred in the first year of surgery,

whereas 74% occurred in the first 2 years.

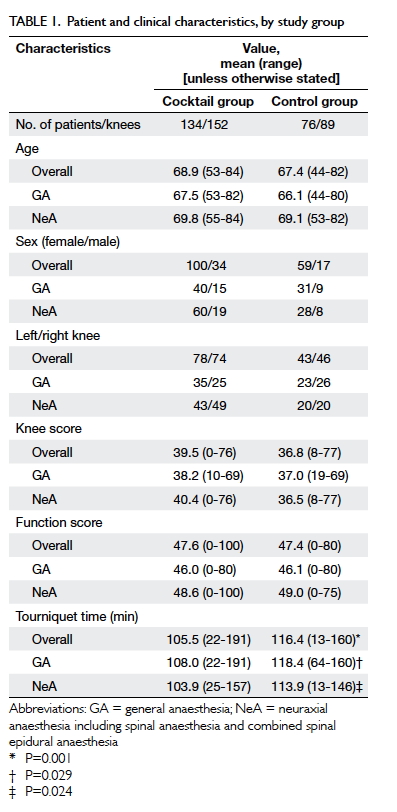

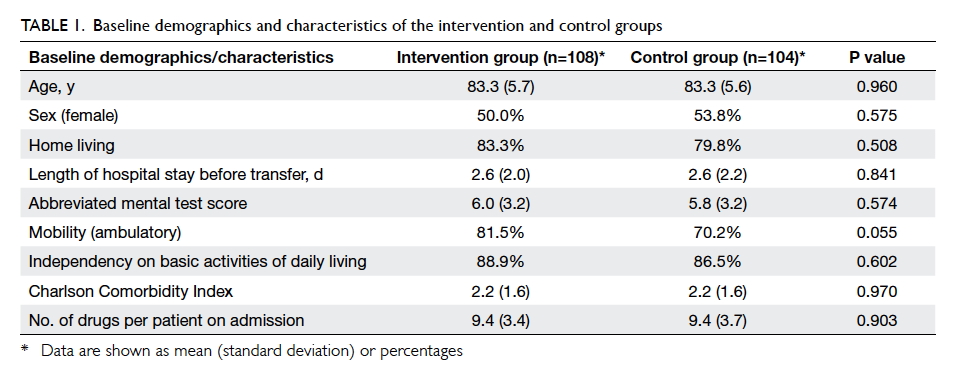

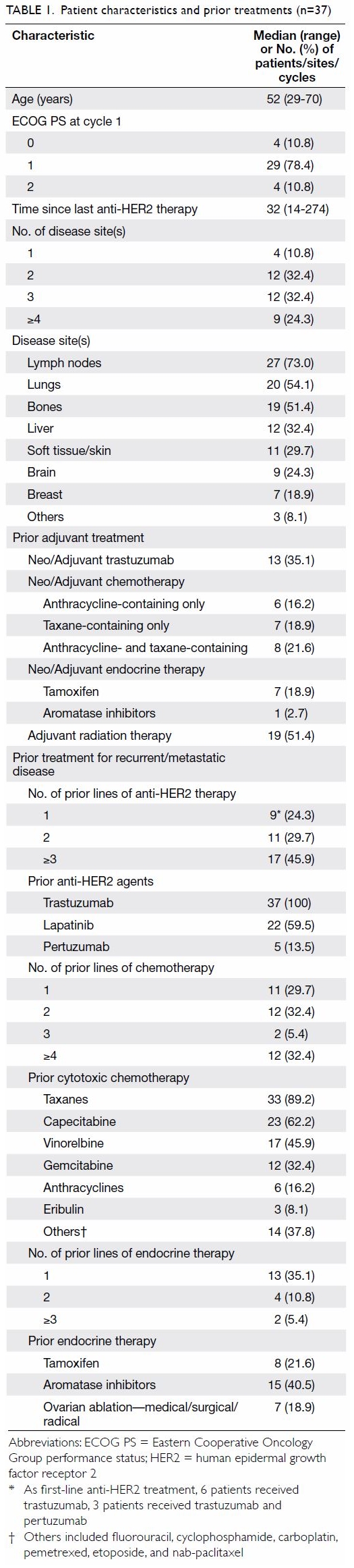

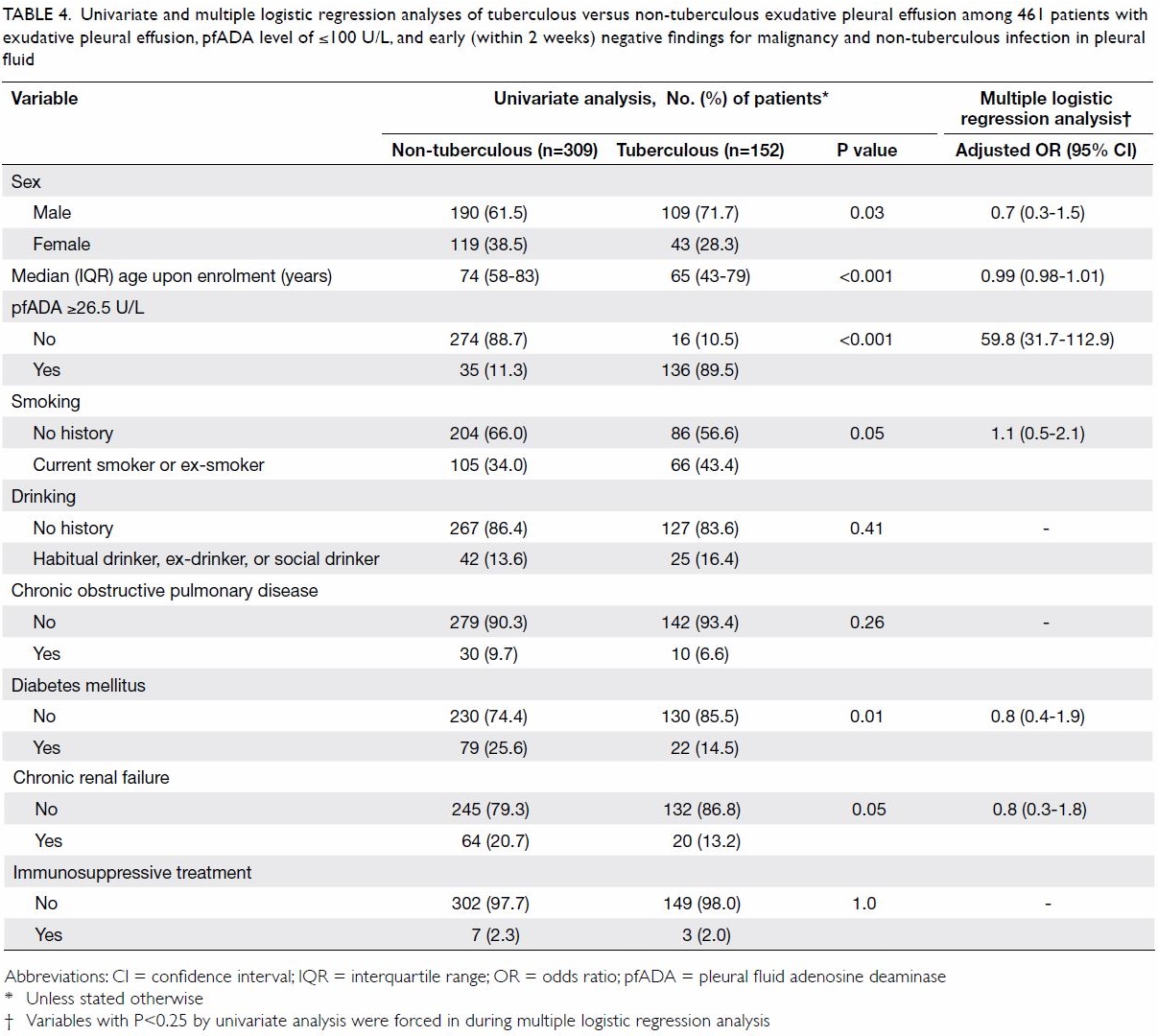

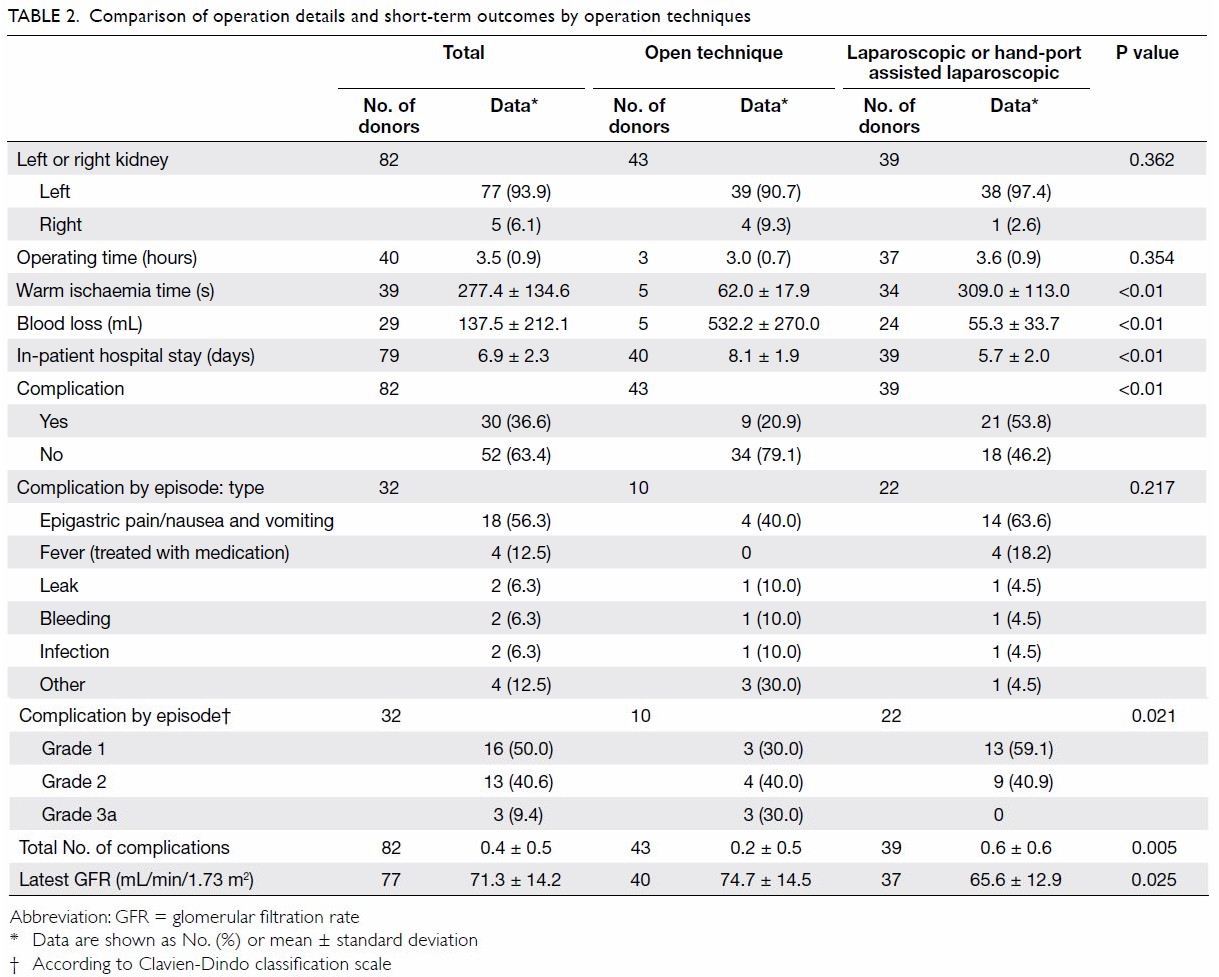

The mean (standard deviation) age was 69 (9) years,

with a range from 21 to 91 years; age followed a normal distribution.

Overall, PJI developed in 10 males (1.9%) and 24 females (1.2%). In the

one-stage bilateral TKA group, PJI occurred in 13 knees (1.2%). For the

single-side TKA group, 21 knees (1.4%) developed PJI. Nine patients with

diabetes (1.9%) and 25 patients without diabetes (1.2%) developed PJI. The

highest rate of PJI, at 3.1%, was found in patients with rheumatoid

arthritis, compared with 1.2% in patients without rheumatoid arthritis.

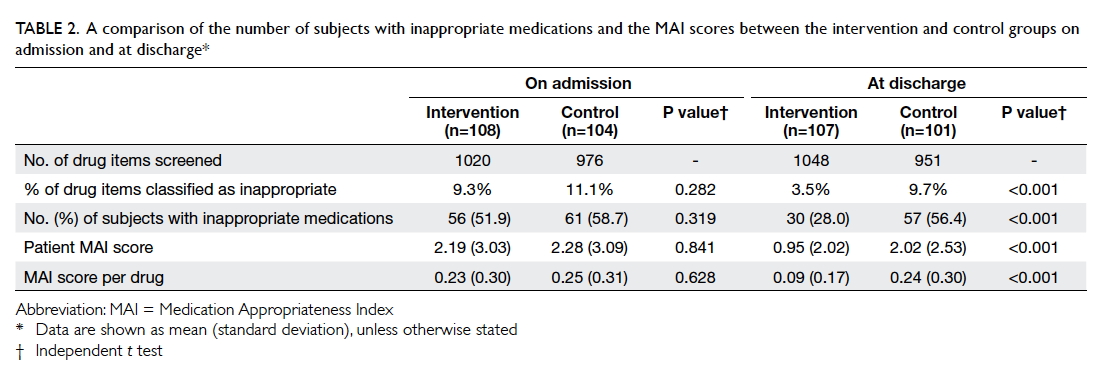

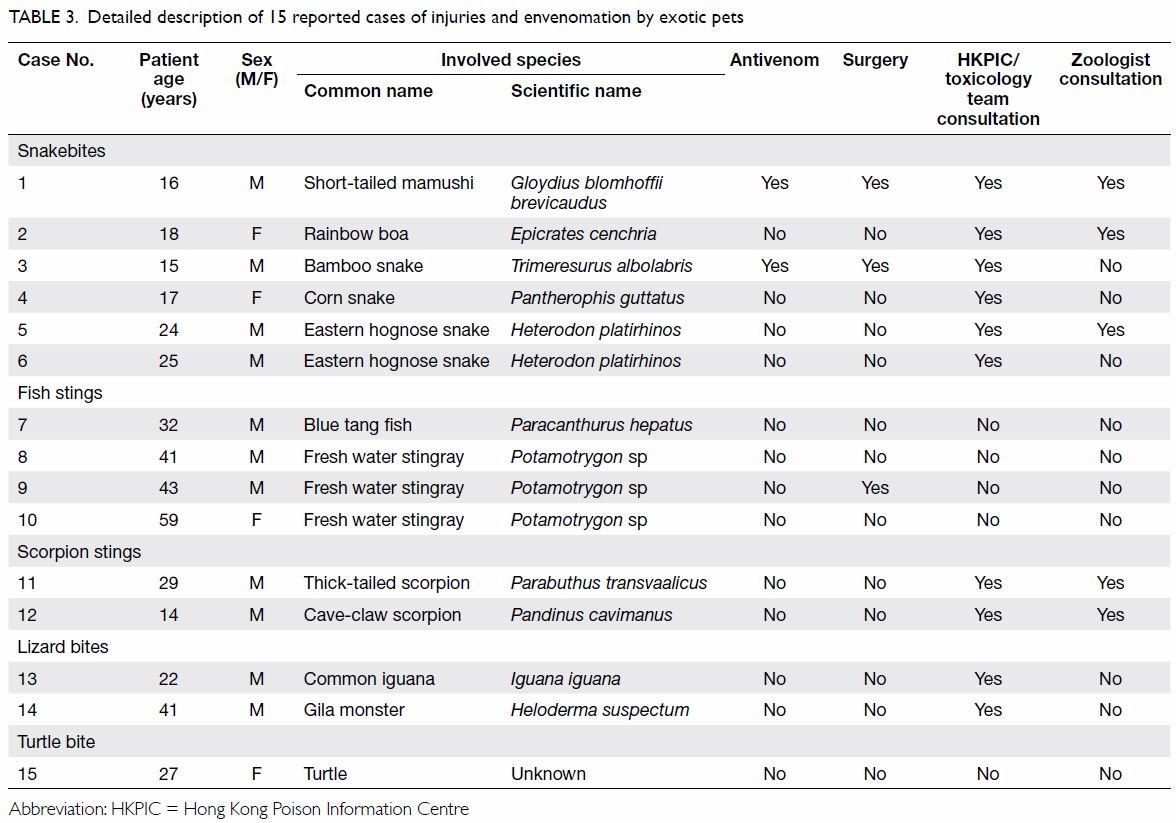

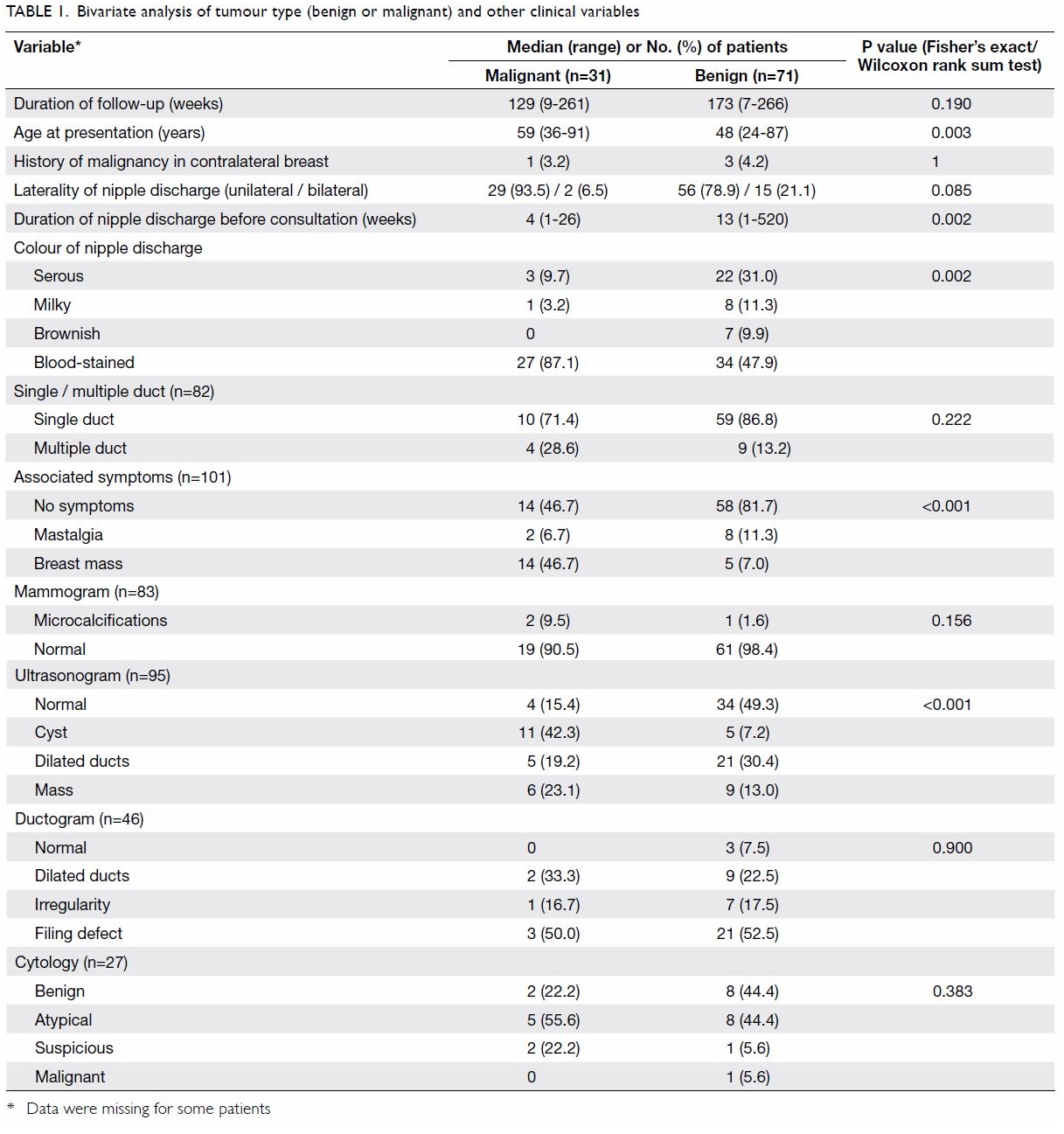

The descriptive data are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for potential risk factors according to occurrence of periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty

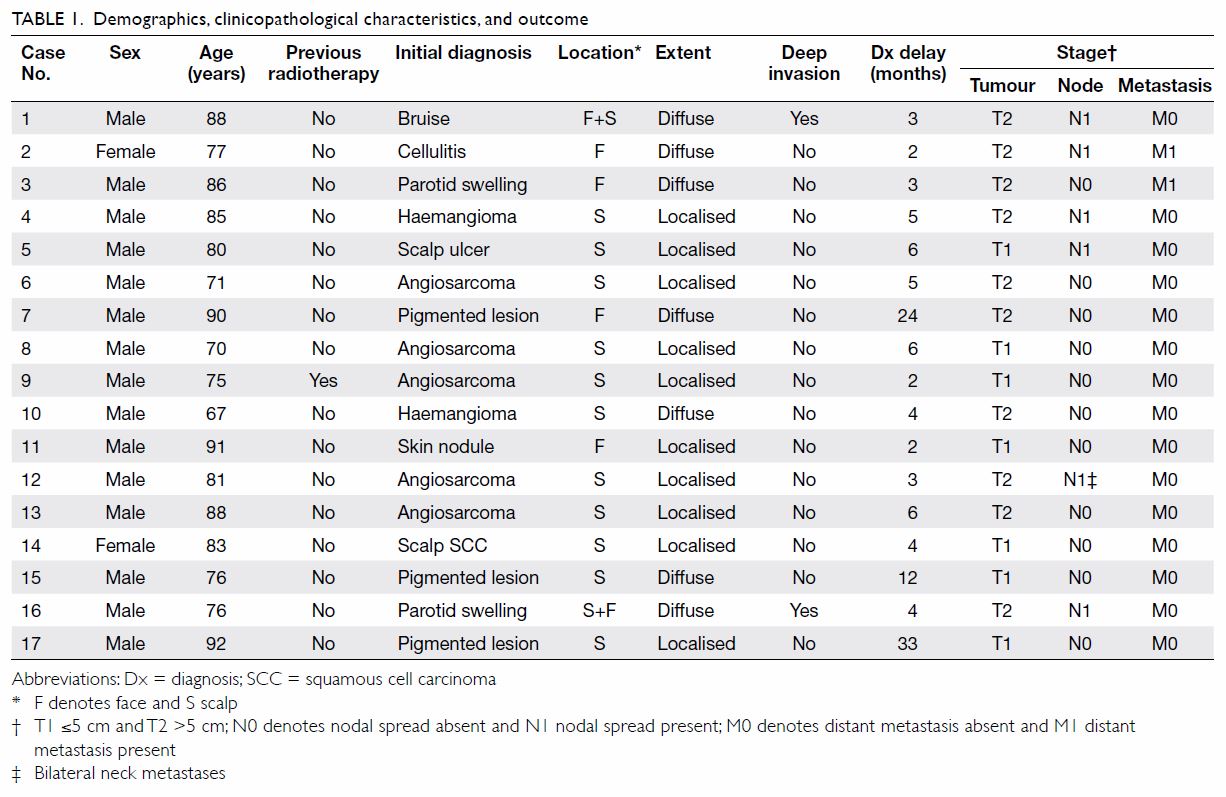

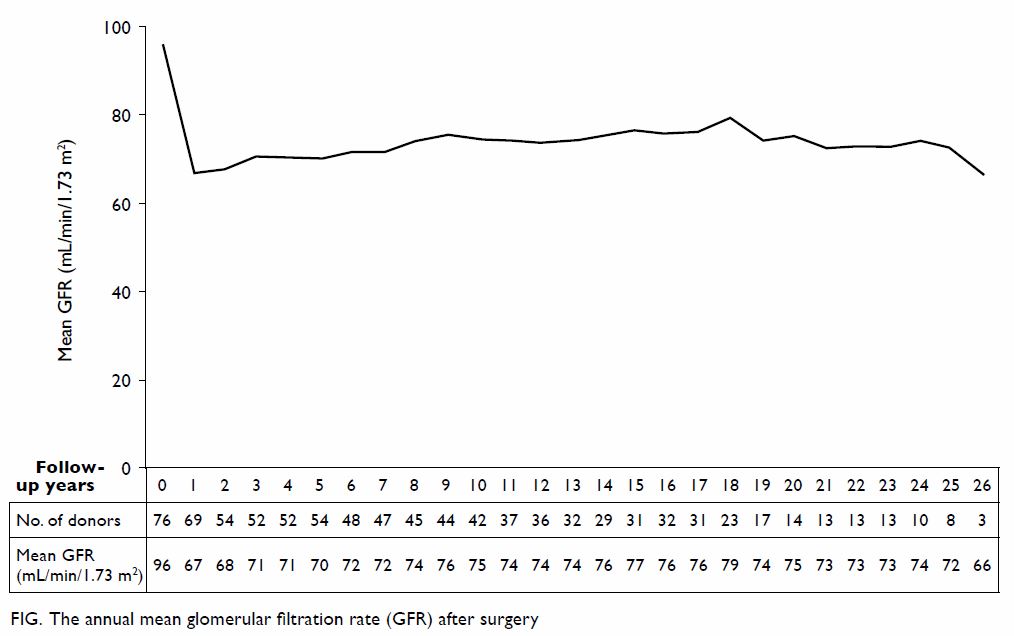

The most frequent causative organism was MSSA

(26.5%, n=9), followed by MRSA (17.6%, n=6), Streptococcus spp

(8.8%, n=3), MSCNS (5.9%, n=2), Escherichia coli (5.9%, n=2), Salmonella

(5.9%, n=2), MRCNS (2.9%, n=1) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis

(2.9%, n=1), The three cases of streptococcal infection comprised two Streptococcus

dysgalactiae infections and one Streptococcus agalactiae

infection. Culture-negative PJI comprised 23.5% of cases (n=8).

Methicillin-resistant strains constituted 39% of all staphylococcal

organisms. There was no significant association between the potential risk

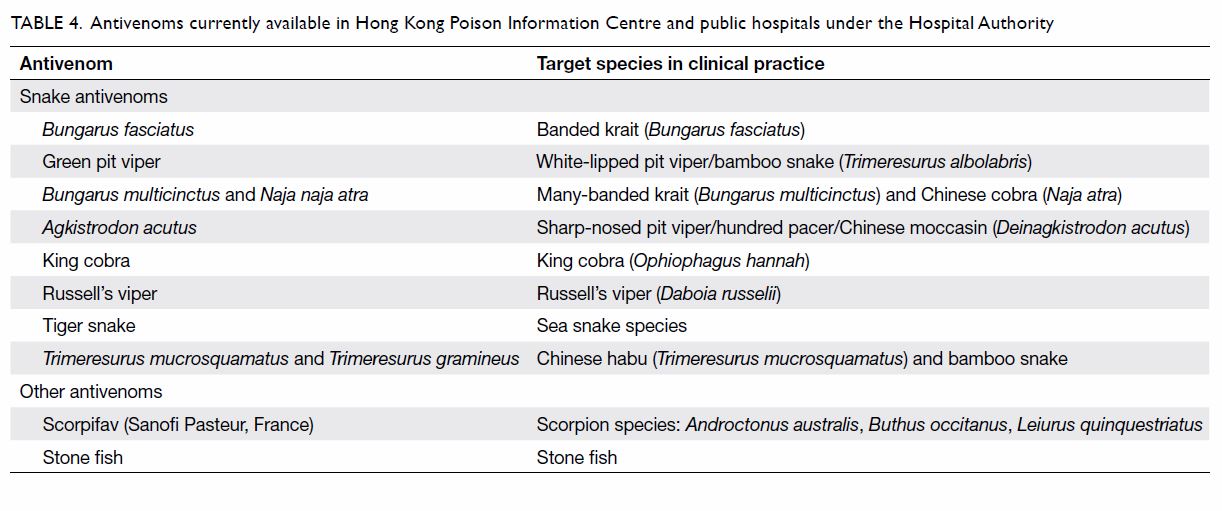

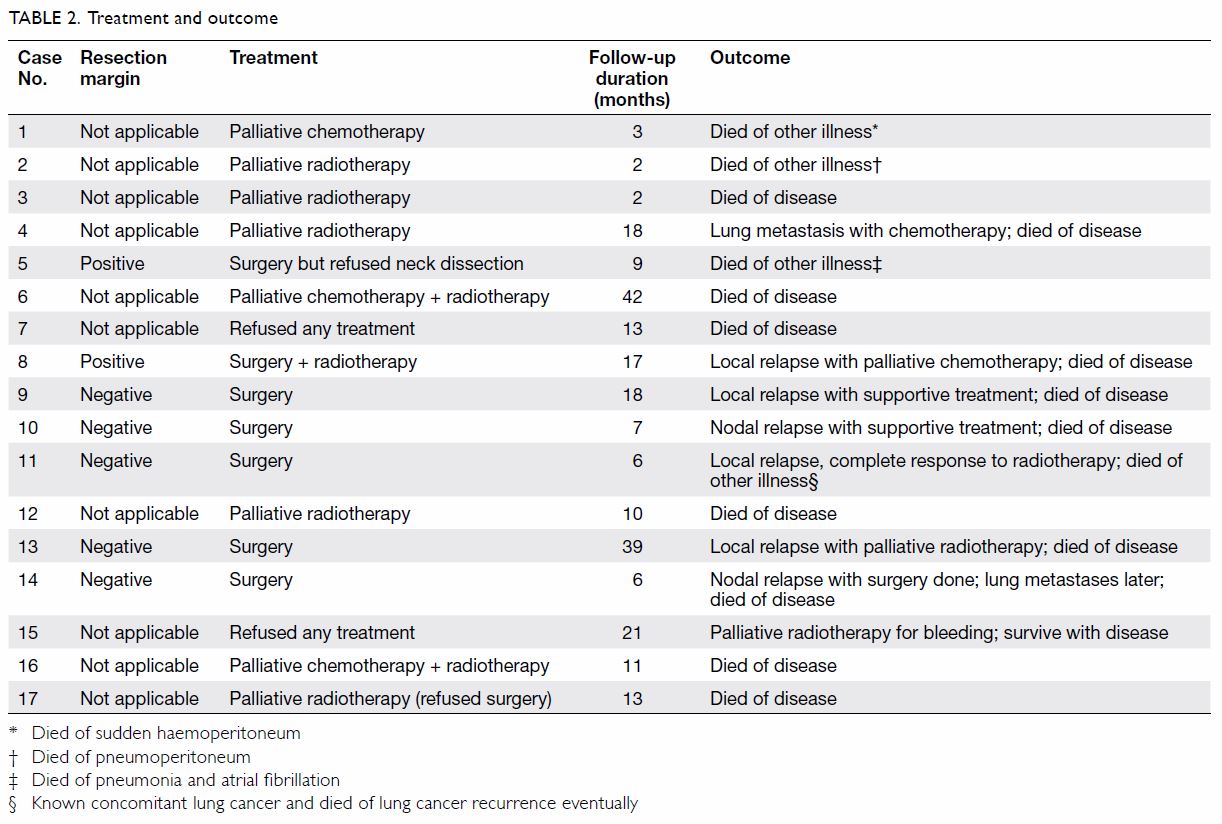

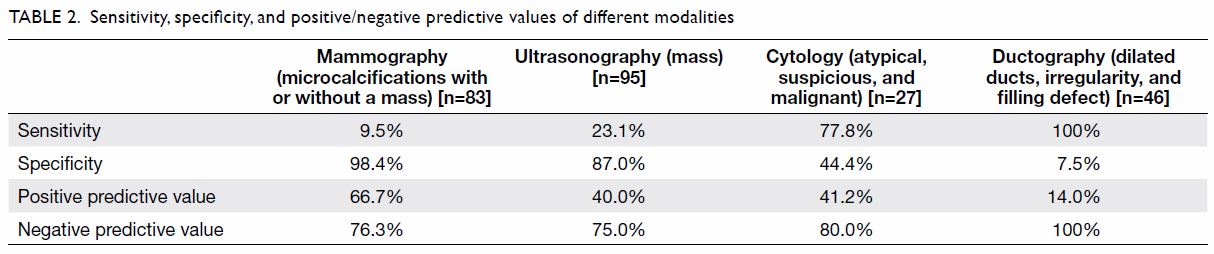

factors and skin flora infection (Table 2).

Table 2. Association between potential risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty and bacteriology

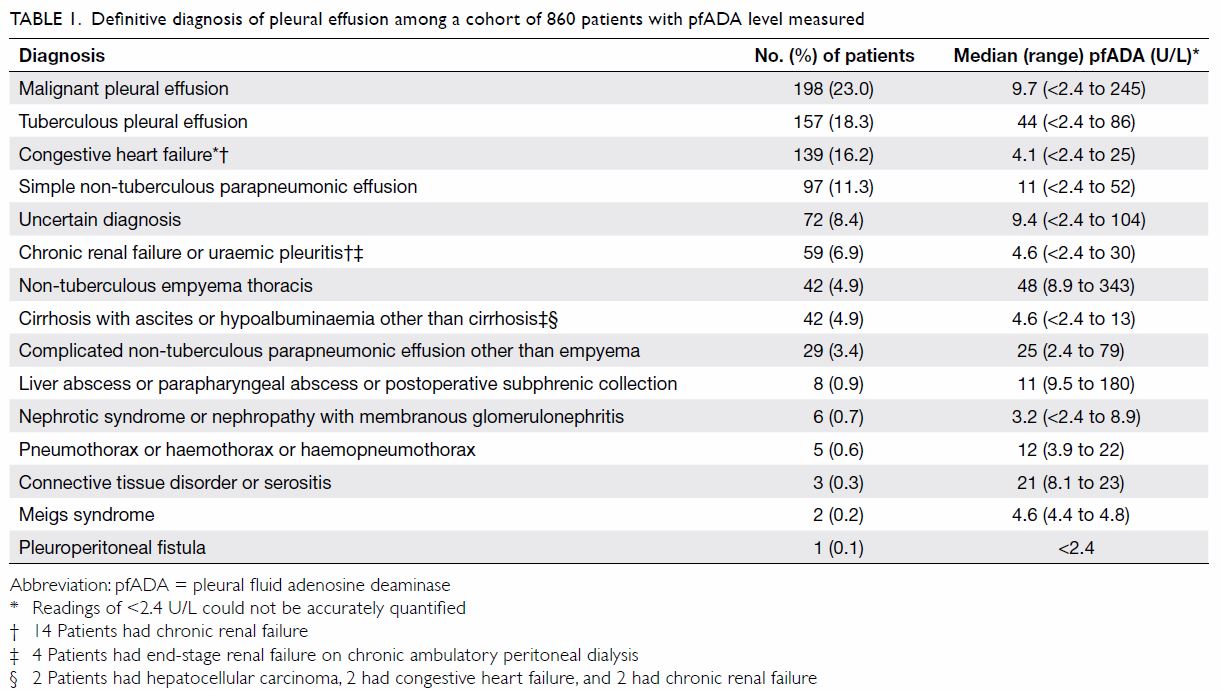

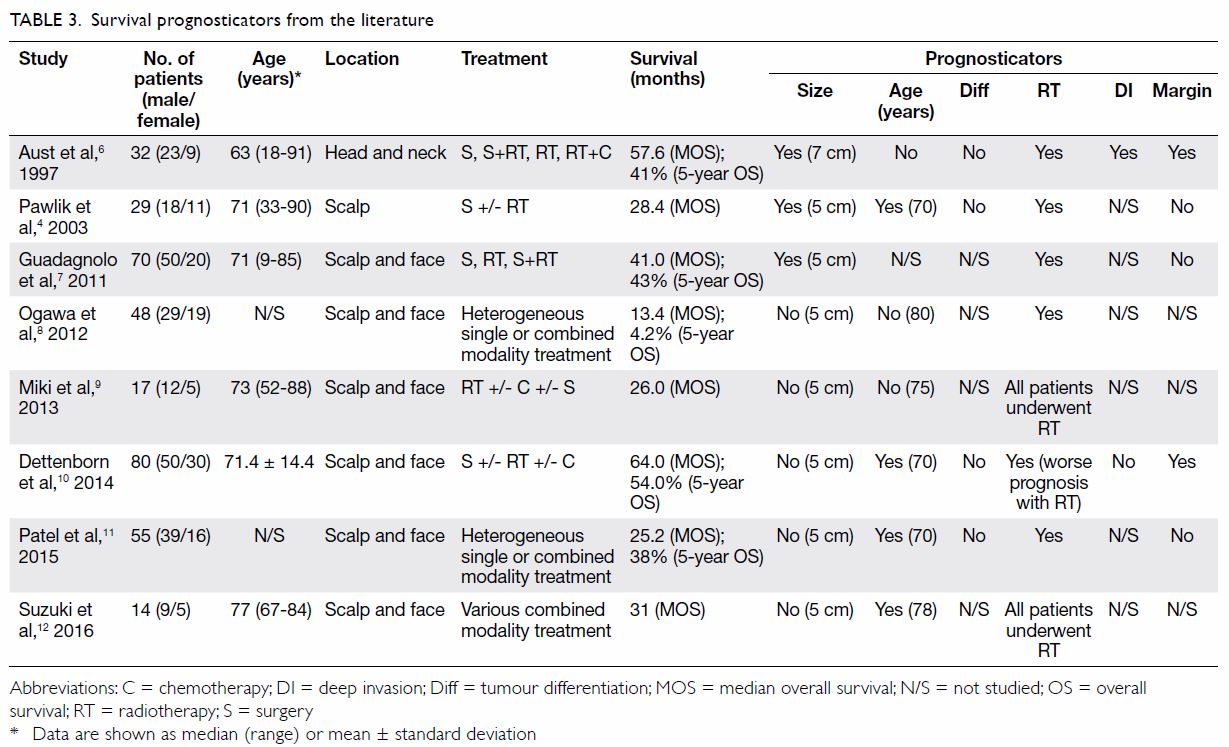

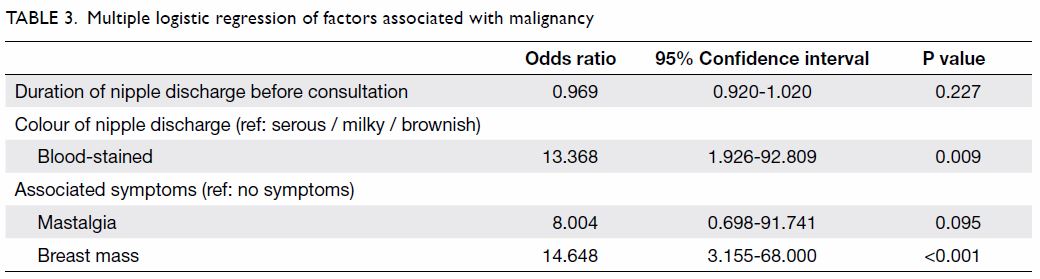

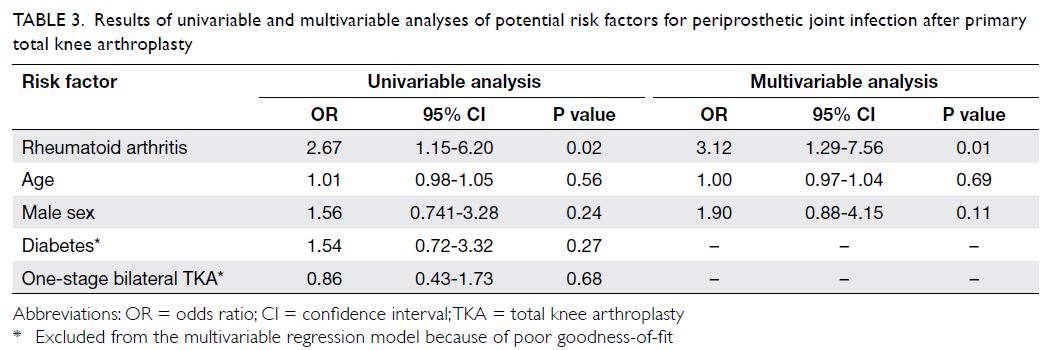

Rheumatoid arthritis was a significant risk factor

of PJI in the univariable analysis, with an OR of 2.67 (95% CI, 1.15-6.20;

P=0.02), as well as in the multivariable analysis, with an OR of 3.12 (CI,

1.29-7.56; P=0.01) [Table 3]. Being male (OR=1.9; P=0.11 in the

multivariable analysis) and having diabetes (OR=1.54; P=0.27 in the

univariable analysis) were not significantly associated with PJI.

Table 3. Results of univariable and multivariable analyses of potential risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty

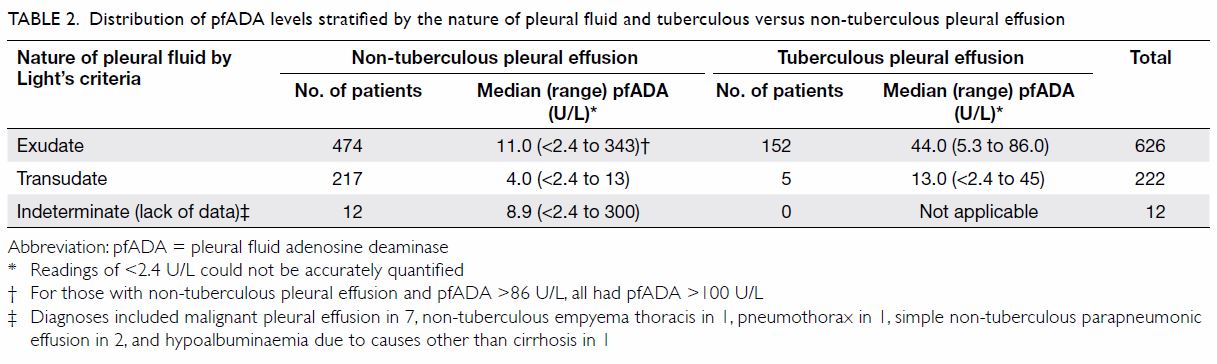

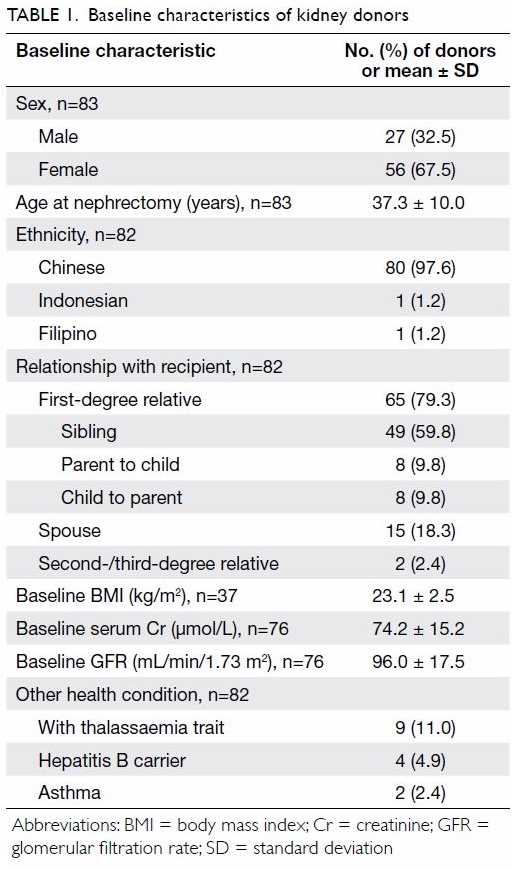

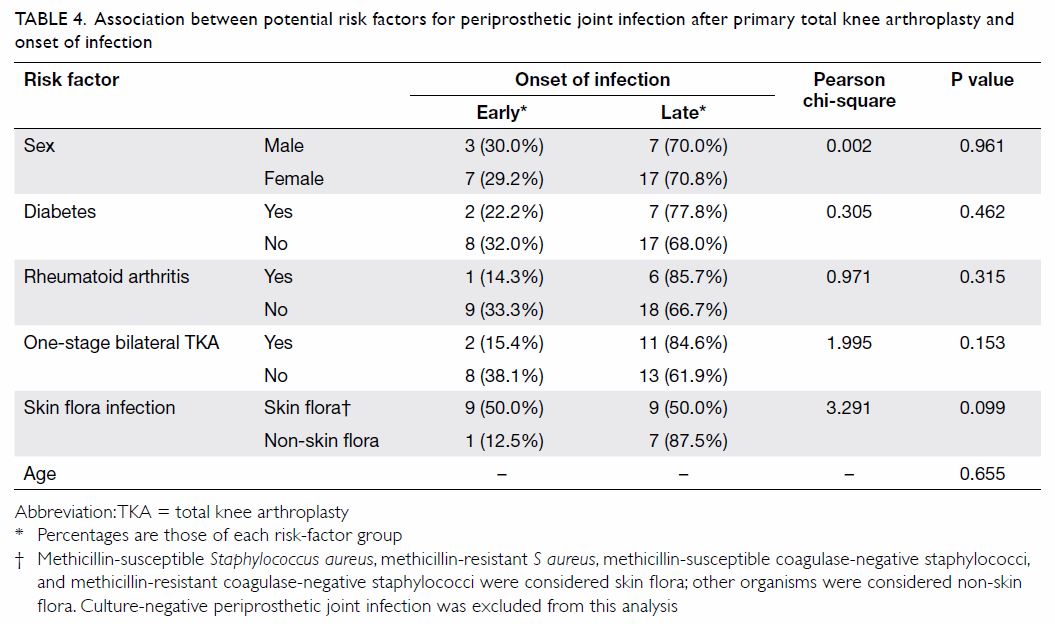

Age (P=0.655), sex (P=0.961), diabetes (P=0.462),

and rheumatoid arthritis (P=0.315) were not associated with early-onset

infection (Table 4). Infection caused by skin flora was

associated with early-onset infection (P=0.099), but the association was

not statistically significant.

Table 4. Association between potential risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty and onset of infection

Discussion

In this study, the incidence of PJI after primary

TKA was 1.34% and the incidence of early-onset infection was 0.39%. The

majority of PJIs (70%) were late-onset infections. The reported incidence

of PJI after primary TKA ranges from 1.1% to 2.18%.16 17 18 Pulido et al16

reported the incidence of PJI after TKA to be 1.1%, of which 27% were

diagnosed during the first 30 days after arthroplasty, and a majority of

65% were diagnosed in the first year after surgery. In our study, the

average time to diagnosis was 431 days after the index surgery (range,

11-1699 days).

Rheumatoid arthritis was a significant risk factor

for PJI after primary TKA. This finding is in keeping with the current

literature.6 8 11 Although

various authors have found male sex to be a risk factor for PJI,4 19 20 the association was not significant in this study.

The OR of 1.9 may be of clinical importance but not significant as a

result of the small number of PJIs and inadequate statistical power. The

correlation between age and PJI has been a matter of controversy, with

some reports mentioning young age as a risk factor for PJI4 21 and some

otherwise.22 In our study, age was

not associated with PJI occurrence. For one-stage bilateral TKA, age has

been a controversial risk factor for PJI. Some studies16 23 have

suggested that one-stage bilateral TKA is associated with an increased

risk of superficial and deep infection. Hussain et al24 nonetheless reported a similar infection rate between

one- and two-stage bilateral TKA. Our study did not find an association

between one-stage bilateral TKA and PJI occurrence.

The local bacteriological pattern for PJI was

comparable to that reported in the literature.4

16 In our study, skin flora and

gram-positive bacteria were the most commonly isolated organisms, followed

by gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common causative organism

in one study.4 In contrast, in our

series, S aureus was the most common causative organism,

particularly methicillin-sensitive strains. Methicillin-resistant strains

were less common in our series, constituting 39% of all staphylococcal

organisms.

Other authors have reported that male sex is a risk

factor for PJI, which may be related to a sex difference in immune

response to pathogenic bacteria. Studies6 have shown that males (compared

with females) have a significantly higher likelihood of being a persistent

S aureus carrier. However, our study did not support male sex as a

risk factor for infection with skin flora. With regard to onset of

infection, PJI caused by skin flora was positively associated with

early-onset infection, although the association did not reach statistical

significance (P=0.099). Direct inoculation and spread from contiguous foci

of infection are more common in early-onset infection caused by wound

complications and local soft-tissue conditions. In contrast, distant foci

of infection, such as in bacteraemia, play a more important role in

late-onset infection. Therefore, in early-onset periprosthetic joint

infection with negative cultures, an empirical antibiotic regimen may

provide adequate coverage against skin flora organisms.

Fan et al20

reported 479 TKAs and rates of 1.9% for superficial wound infection, 0.2%

for early deep infection (n=1), and 0.6% for late deep infection (n=2).

Methicillin-sensitive S aureus and coagulase-negative

staphylococci were causative organisms. Lee et al25

reviewed 1133 primary TKAs and found a 0.71% incidence of PJI. The most

common causative organisms in descending order were methicillin-sensitive

S aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, methicillin-resistant S

aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This finding is in

keeping with our data. Among risk factors identified by Lee et al25 were young age, diabetes, anaemia, thyroid disease,

heart disease, lung disease, and long operating time. However, the

researchers identified limitations of having only a small number of

patients with infection (n=8) and insufficient power for analysis. In

addition, multivariable analysis should have been performed to account for

the effect of confounders among the multiple risk factors. They also

reported the limitation that the mean follow-up duration was only 2 years.

A short follow-up period may underestimate the occurrence of late-onset

infection.

Our study has several limitations. The number of

PJI-positive cases was small and thus subgroup analysis was limited. This

study included subjects treated at a single centre in Hong Kong;

multicentre studies may improve the representativeness of local data. In

addition, perioperative management for elective TKA has evolved over the

past 20 years, including the introduction of an MRSA-screening programme

in 2011. In the screening programme, a nasal swab is taken from all

elective joint-replacement patients. Patients with a positive result are

prescribed 5 days of decolonisation therapy including a daily

chlorhexidine bath. Furthermore, intravenous vancomycin is now

administered for prophylaxis instead of cefazolin.26

There are many potential risk factors for PJI

documented in the literature. Nonetheless, only a limited number were

included in this study, most of which are not be modifiable. Thus, it may

not provide the necessary guidance for preoperative optimisation.

Furthermore, the exclusion of some potential risk factors may have led to

inadequate control for potential confounding factors. Inclusion of more

risk factors with better characterisation is needed to provide a more

comprehensive understanding and to better account for the confounding

effect of other variables.

Conclusion

The incidence of PJI after elective primary TKA in

our institution over two decades from 1993 to 2013 was 1.34%. Rheumatoid

arthritis was a significant risk factor for PJI in this series. In the

early-onset infection group, PJI was caused by skin flora, but this was

not statistically significant. It is hoped that this study has updated the

local data for PJI after primary TKA and serves as a model for future

related studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues from the Department of

Orthopaedics and Traumatology and the Infection Control Team at the Queen

Mary Hospital for their assistance in data collection, and those who

advised on this project to make its publication possible.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

References

1. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK,

Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United

States. J Arthroplasty 2012;27(8 Suppl):61-5.e1. CrossRef

2. Lamarsalle L, Hunt B, Schauf M,

Szwarcensztein K, Valentine WJ. Evaluating the clinical and economic

burden of healthcare-associated infections during hospitalization for

surgery in France. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:2473-82. CrossRef

3. Nero DC, Lipp MJ, Callahan MA. The

financial impact of hospital-acquired conditions. J Health Care Finance

2012;38:40-9.

4. Crowe B, Payne A, Evangelista PJ, et al.

Risk factors for infection following total knee arthroplasty: a series of

3836 cases from one institution. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:2275-8. CrossRef

5. Meller MM, Toossi N, Johanson NA,

Gonzalez MH, Son MS, Lau EC. Risk and cost of 90-day complications in

morbidly and superobese patients after total knee arthroplasty. J

Arthroplasty 2016;31:2091-8. CrossRef

6. Zmistowski B, Alijanipour P. Risk

factors for periprosthetic joint infection. In: Springer BD, Parvizi J,

editors. Periprosthetic Joint Infection of the Hip and Knee. New York:

Springer; 2014: 15-40. CrossRef

7. Jämsen E, Huhtala H, Puolakka T,

Moilanen T. Risk factors for infection after knee arthroplasty. A

register-based analysis of 43,149 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am

2009;91:38-47. CrossRef

8. Wilson MG, Kelley K, Thornhill TS.

Infection as a complication of total knee-replacement arthroplasty. Risk

factors and treatment in sixty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am

1990;72:878-83. CrossRef

9. Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW. Risk

factors associated with deep surgical site infections after primary total

knee arthroplasty: an analysis of 56,216 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am

2013;95:775-82. CrossRef

10. Pruzansky JS, Bronson MJ, Grelsamer

RP, Strauss E, Moucha CS. Prevalence of modifiable surgical site infection

risk factors in hip and knee joint arthroplasty patients at an urban

academic hospital. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:272-6. CrossRef

11. Chesney D, Sales J, Elton R, Brenkel

IJ. Infection after knee arthroplasty: a prospective study of 1509 cases.

J Arthroplasty 2008;23:355-9. CrossRef

12. Moucha CS, Clyburn T, Evans RP,

Prokuski L. Modifiable risk factors for surgical site infection. J Bone

Joint Surg Am 2011;93:398-404.

13. Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J,

Peterson M. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of

6489 total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;392:15-23. CrossRef

14. Rasouli MR, Restrepo C, Maltenfort MG,

Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Risk factors for surgical site infection following

total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:e158. CrossRef

15. Parvizi J, Gehrke T; International

Consensus Group on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Definition of

periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1331. CrossRef

16. Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill

JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and

predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:1710-5. CrossRef

17. Tsaras G, Osmon DR, Mabry T, et al.

Incidence, secular trends, and outcomes of prosthetic joint infection: a

population based study, Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1969-2007. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:1207-12. CrossRef

18. Tande AJ, Patel R. Prosthetic joint

infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014;27:302-45. CrossRef

19. Herwaldt LA, Cullen JJ, French P, et

al. Preoperative risk factors for nasal carriage of Staphylococcus

aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004;25:481-4. CrossRef

20. Fan JC, Hung HH, Fung KY. Infection in

primary total knee replacement. Hong Kong Med J 2008;14:40-5.

21. Meehan JP, Danielsen B, Kim SH, Jamali

AA, White RH. Younger age is associated with a higher risk of early

periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic mechanical failure after total

knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:529-35. CrossRef

22. Berbari EF, Osmon DR, Lahr B, et al.

The Mayo prosthetic joint infection risk score: implication for surgical

site infection reporting and risk stratification. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol 2012;33:774-81. CrossRef

23. Luscombe JC, Theivendran K, Abudu A,

Carter SR. The relative safety of one-stage bilateral total knee

arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2009;33:101-4. CrossRef

24. Hussain N, Chien T, Hussain F, et al.

Simultaneous versus staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a

meta-analysis evaluating mortality, peri-operative complications and

infection rates. HSS J 2013;9:50-9. CrossRef

25. Lee QJ, Mak WP, Wong YC. Risk factors

for periprosthetic joint infection in total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop

Surg (Hong Kong) 2015;23:282-6. CrossRef

26. Cheng VC, Tai JW, Wong ZS, et al.

Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the long

term care facilities in Hong Kong. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:205. CrossRef