The first pilot study of expanded newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism and survey of related knowledge and opinions of health care professionals in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2018 Jun;24(3):226–37 | Epub 4 Jun 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176939

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The first pilot study of expanded newborn screening for

inborn errors of metabolism and survey of related knowledge and opinions

of health care professionals in Hong Kong

Chloe M Mak, MD, FHKAM (Pathology)1;

Eric CY Law, PhD, FHKAM (Pathology)2,3; Hencher HC Lee, MA,

FRCPA1; WK Siu, PhD, FHKAM (Pathology)1; KM Chow,

FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4; Sidney KC Au Yeung,

FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)5; Hextan YS Ngan,

FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)6; Niko KC Tse,

FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)7; NS Kwong, FHKCPaed, FHKAM

(Paediatrics)8; Godfrey CF Chan, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)9;

KW Lee, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4; WP Chan,

MB, ChB, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4; SF Wong, FRCOG,

FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)5; Mary HY Tang, FRCOG, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology)6; Anita SY Kan, MRCOG, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology)6; Amelia PW Hui, FRCOG, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology)6; PL So, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics

and Gynaecology)5; CC Shek, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)7;

Robert SY Lee, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)7; KY Wong, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)9;

Eric KC Yau, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)7; KH Poon, MRCP(UK),

FHKCPaed8; Sylvia Siu, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)8;

Grace WK Poon, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)9; Anne MK Kwok,

FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)9; Judy WY Ng, BAppSc(Nurs), MSSc

(Counselling)4; Vera CS Yim, FHKAN (HKCMW), MSC5;

Grace GY Ma, BSN, MHSM (Health Services Management)6; CH Chu,

MS10; TY Tong, MSc1; YK Chong, FHKCPath, FHKAM

(Pathology)1; Sammy PL Chen, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)1;

CK Ching, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)1; Angel OK Chan, MD, FHKAM

(Pathology)3; Sidney Tam, FRCP, FHKAM (Pathology)4;

Ruth LK Lau, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Pathology)11; WF Ng, MB, ChB,

FHKAM (Pathology)11; KC Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Pathology)1;

Albert YW Chan, MD, FHKAM (Pathology)1; CW Lam, PhD, FHKAM

(Pathology)2

1 Chemical Pathology Laboratory,

Department of Pathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, The

University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

3 Division of Clinical Biochemistry,

Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

5 Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

6 Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

7 Department of Paediatrics and

Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

8 Department of Paediatrics and

Adolescent Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

9 Department of Paediatrics and

Adolescent Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

10 Department of Pathology, United

Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

11 Department of Pathology, Yan Chai

Hospital, Tsuen Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CW Lam (ching-wanlam@pathology.hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Newborn screening

is important for early diagnosis and effective treatment of inborn

errors of metabolism (IEM). In response to a 2008 coroners’ report of a

14-year-old boy who died of an undiagnosed IEM, the OPathPaed service

model was proposed. In the present study, we investigated the

feasibility of the OPathPaed model for delivering expanded newborn

screening in Hong Kong. In addition, health care professionals were

surveyed on their knowledge and opinions of newborn screening for IEM.

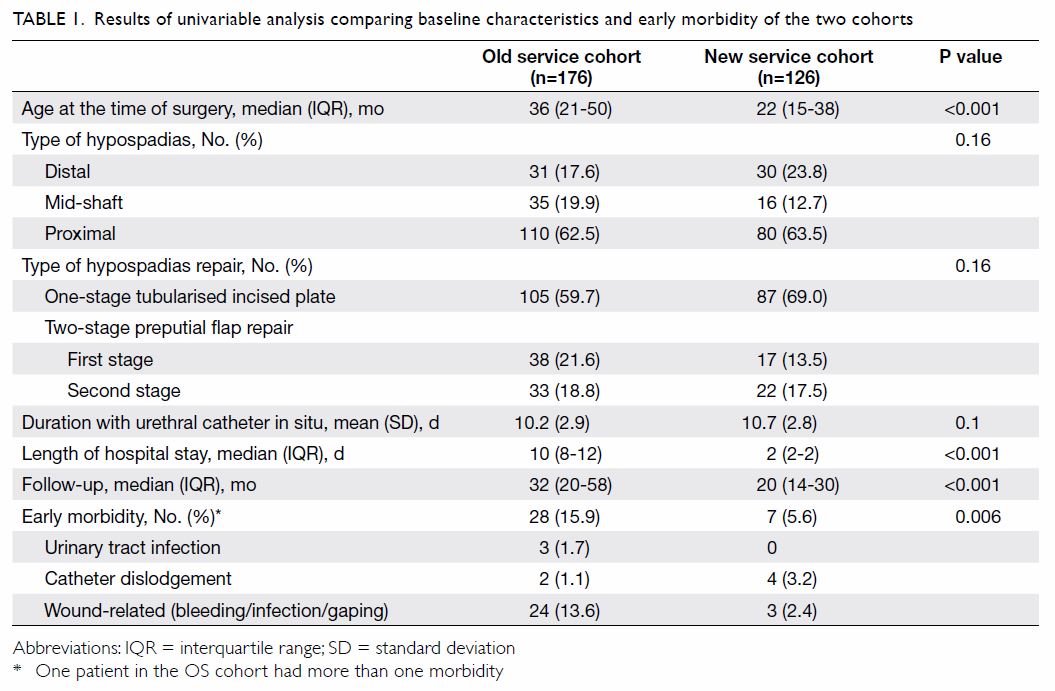

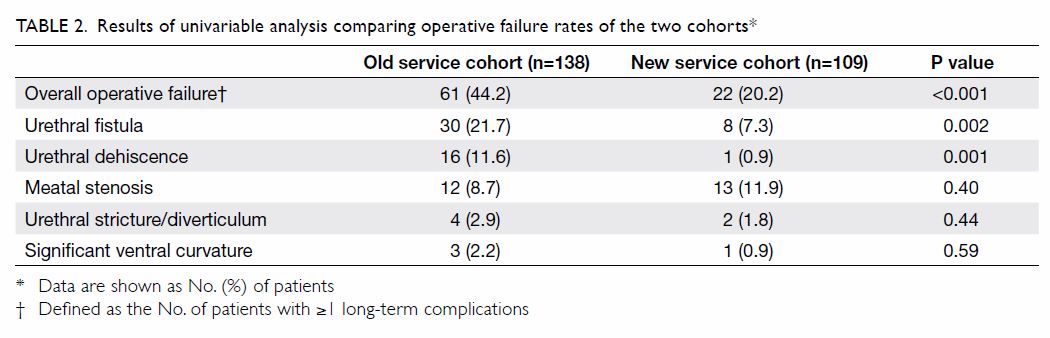

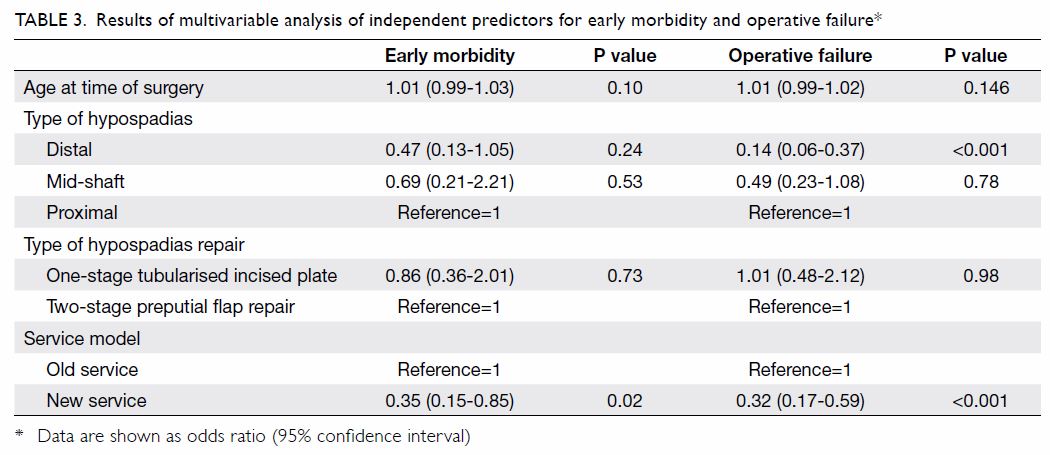

Methods: The present prospective

study involving three regional hospitals was conducted in phases, from 1

October 2012 to 31 August 2014. The 10 steps of the OPathPaed model were

evaluated: parental education, consent, sampling, sample dispatch, dried

blood spot preparation and testing, reporting, recall and counselling,

confirmation test, treatment and monitoring, and cost-benefit analysis.

A fully automated online extraction system for dried blood spot analysis

was also evaluated. A questionnaire was distributed to 430 health care

professionals by convenience sampling.

Results: In total, 2440 neonates

were recruited for newborn screening; no true-positive cases were found.

Completed questionnaires were received from 210 respondents. Health care

professionals supported implementation of an expanded newborn screening

for IEM. In addition, there is a substantial need of more education for

health care professionals. The majority of respondents supported

implementing the expanded newborn screening for IEM immediately or

within 3 years.

Conclusion: The feasibility of

OPathPaed model has been confirmed. It is significant and timely that

when this pilot study was completed, a government-led initiative to

study the feasibility of newborn screening for IEM in the public health

care system on a larger scale was announced in the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region Chief Executive Policy Address of 2015.

New knowledge added by this study

- The feasibility of the OPathPaed service model was evaluated in 2440 neonates. The main focus was on parental education, consent, sampling, sample dispatch, dried blood spot preparation and testing, reporting, recall, and counselling.

- Of 210 health care professionals who responded to a survey, 73.6% were unaware of newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism (IEM), 87.6% urged for more education, and 91.3% supported implementing expanded newborn screening for IEM immediately or within 3 years.

- The OPathPaed service model for implementing expanded newborn screening for IEM is feasible for local public hospital settings.

- Health care professionals support implementation of newborn screening for IEM. In addition, there is a substantial need of more education.

Introduction

The expansion of newborn screening (NBS) for

various genetic disorders with a focus on inborn errors of metabolism

(IEM) has become a mandatory part of health care policy worldwide.

Multiplex testing by tandem mass spectrometry has extended the scope of

NBS far beyond the traditional ‘one test for one disease’ paradigm,

requiring only a tiny blood sample, obtained by a simple heel prick.1 2 As a result,

many inherited diseases are now screened for to allow early diagnosis and

intervention and thereby prevent permanent damage or potential deaths.

Inborn errors of metabolism are a group of rare

metabolic diseases with heterogeneous clinical presentations and genetic

aetiologies. They are individually rare but collectively common. In 2011,

Lee et al3 reported a 5-year

retrospective review on the laboratory diagnosis of amino acid disorders,

organic acidurias, and fatty acid beta-oxidation defects in three regional

hospitals. The overall local incidence of classical IEM was 1 in 4122 live

births.3 No phenylketonuria was

identified through the screening of 18 000 newborns in the early 1970s.4 Hyperphenylalaninaemia was the

second most common amino acid disorder reported by Lee et al,3 with an incidence of 1 in 29 542 live births. Another

study by Hui et al5 reported the

overall incidence of common IEM as 1 in 5400. According to the Hong Kong

Paediatric Metabolic Registry, there were two cohorts, the first one with

20 years from 1982 to 2002 with 89 IEM patients and the second one with 14

years from 1996 to 2010 with 120 IEM patients. The estimated incidence of

IEM was 1 in 7580 (unpublished data); however, as that was a voluntary

case-finding study from several hospitals, the incidence was likely to be

an underestimate. These figures are similar to those reported worldwide,

such as 1 in 5800 in mainland China,6

1 in 5882 in Taiwan,7 and 1 in 4000

in America.8

In 2000, a mandatory NBS programme for

hyperphenylalaninaemia, congenital hypothyroidism, and congenital deafness

was implemented in mainland China.9

In 2006, the American College of Medical Genetics recommended 29 metabolic

diseases (IEM) for which screening should be mandated.10 Since then, the scope of this recommendation has been

expanding (Recommended Uniform Screening Panel, the Secretary of the

Department of Health and Human Services11).12 In Hong Kong, population

screening for congenital hypothyroidism and glucose-6-phosphate

dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency using umbilical cord blood has been

mandatory since March 1984 under the Neonatal Screening Unit of the

Clinical Genetic Service, Department of Health. This programme has

resulted in a significant reduction in related morbidities and

mortalities.

In 2008, a coroner inquest was called to

investigate the sudden death of a 14-year-old boy with a postmortem

genetic diagnosis of glutaric acidaemia type II.13

The Coroners’ Report demanded that “The Department of Health, the Hospital

Authority, the Faculty of Medicine of various universities and others

concerned should carry out a feasibility study to see whether universal

check may be carried out on all newborn babies for congenital metabolism

defect.”14

To be effective, an expanded NBS programme needs to

be coupled with improved general awareness of IEM and NBS. Educational

support and training are required for frontline clinicians engaged in the

diagnosis and care of patients with IEM.15

Several studies have shown that health care professionals do not have

satisfactory awareness and knowledge of IEM.15

16 17

18 Therefore, a better

understanding of the awareness of IEM among health care professionals in

Hong Kong is needed.

We have conducted the first feasibility pilot study

on the expanded NBS service model in a hospital setting in Hong Kong and

the first survey on the knowledge and opinions on NBS for IEM among health

care professionals in Hong Kong.

Methods

This prospective pilot study was conducted in

phases from 1 October 2012 to 31 August 2014, involving three public

hospitals and The University of Hong Kong (HKU), with over 40

collaborators from departments of pathology, paediatrics, and obstetrics.

Phases 1 and 2 involved a single-site study conducted at Princess Margaret

Hospital from 1 October 2012 to 31 October 2013 and then at Tuen Mun

Hospital from 1 November 2013 to 31 March 2014. Phase 3 was university

(HKU)-based and the recruitment was open to the public from 3 March 2014

to 31 August 2014. Phase 4 was a two-site study at the Tuen Mun Hospital

and Queen Mary Hospital from 4 April 2014. Phase 5 was carried out at all

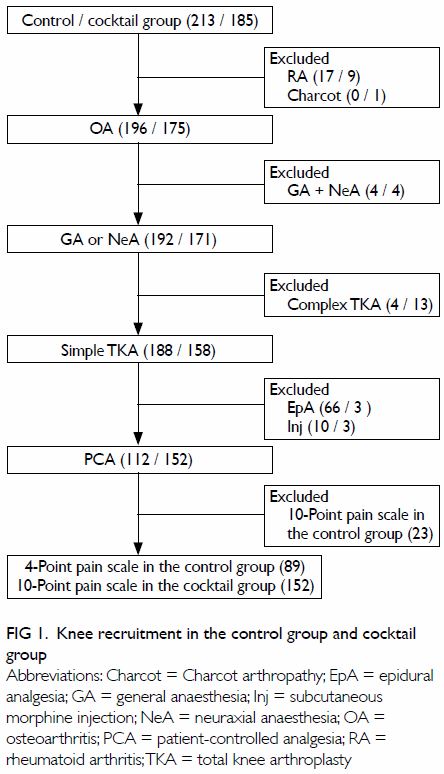

three hospitals from 2 July 2014 until 31 August 2014. The OPathPaed model

for expanded NBS was used for evaluation.19

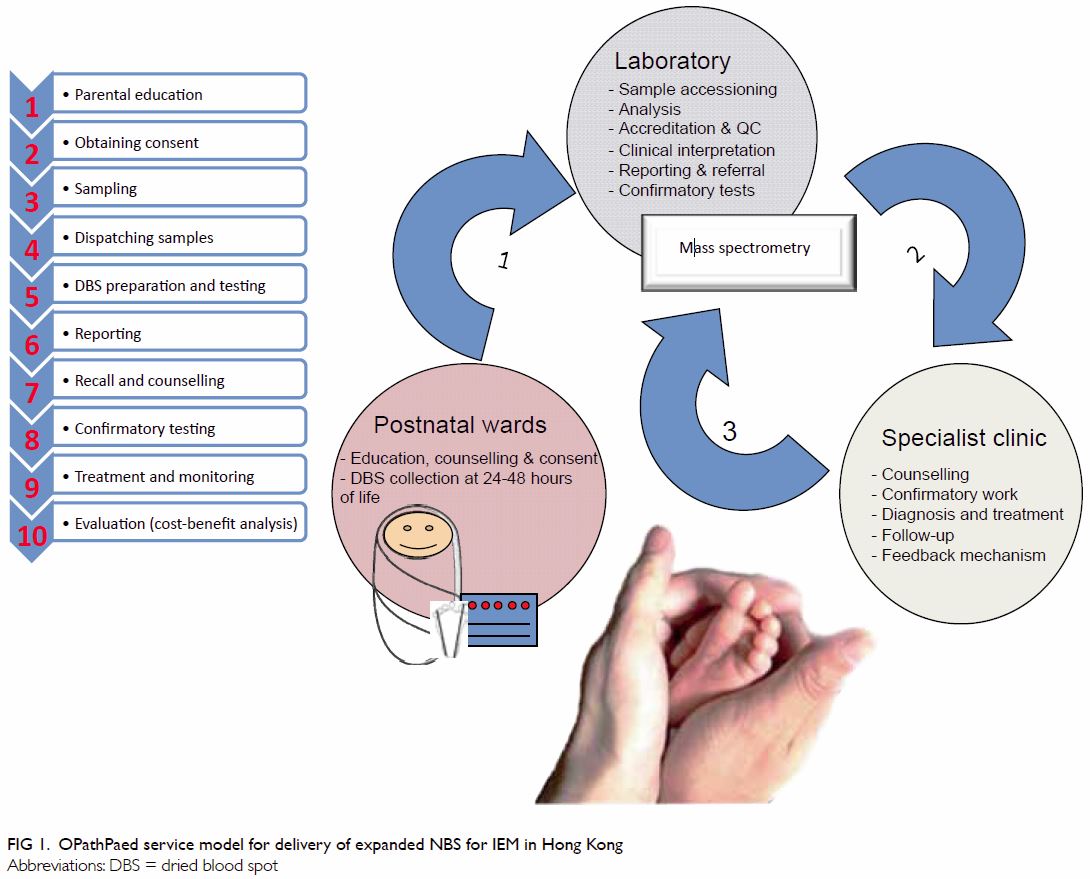

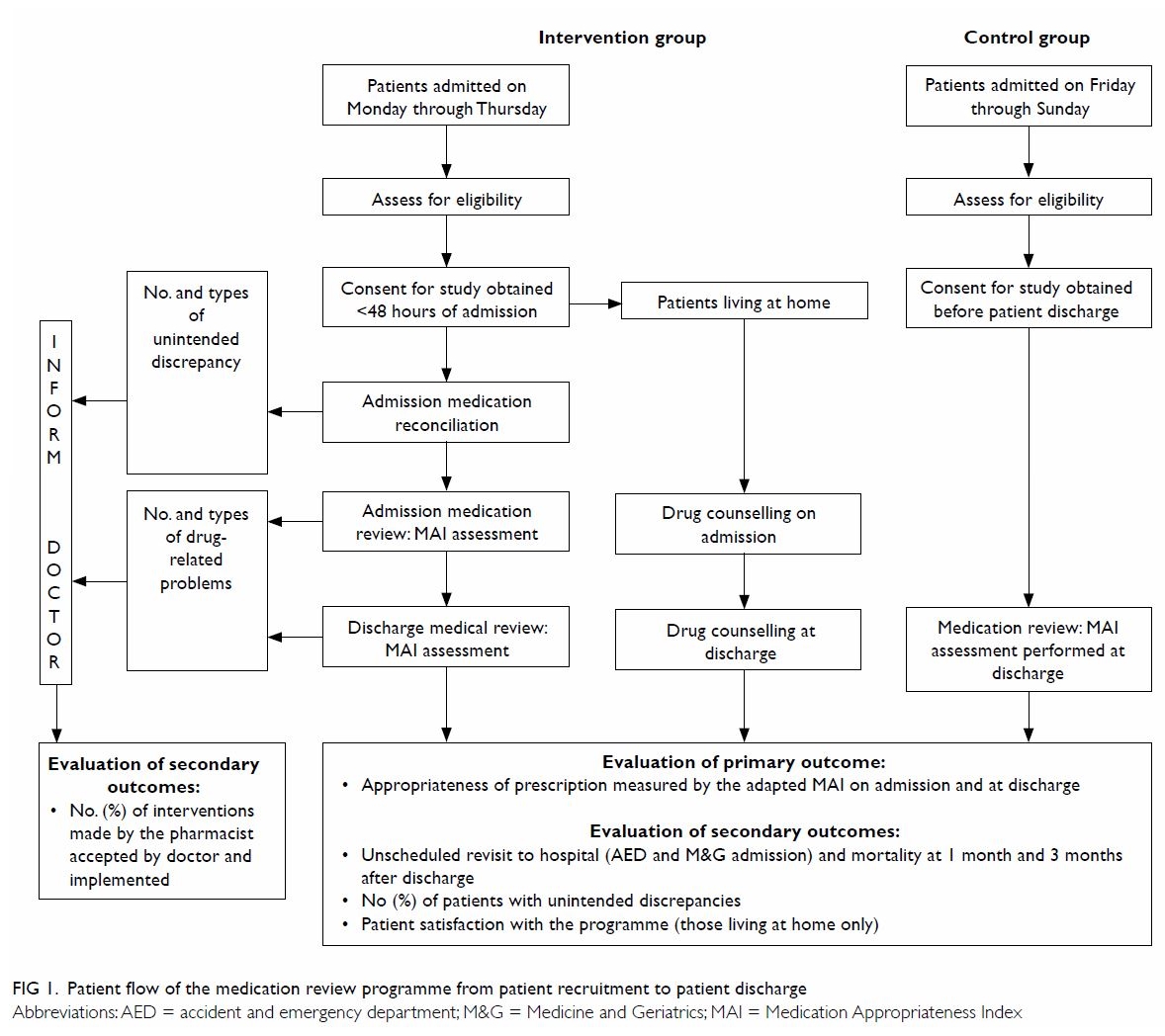

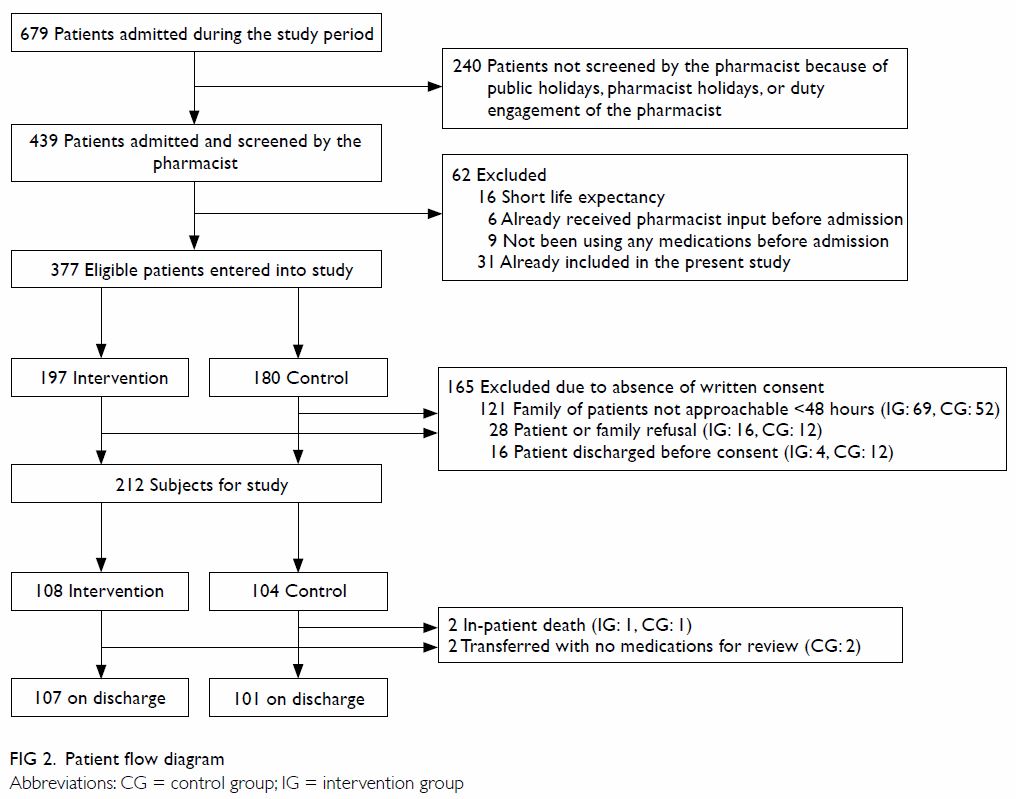

The OPathPaed model includes 10 steps: parental education, consent,

sampling, sample dispatch, dried blood spot (DBS) preparation and testing,

reporting, recall and counselling, confirmation test, treatment and

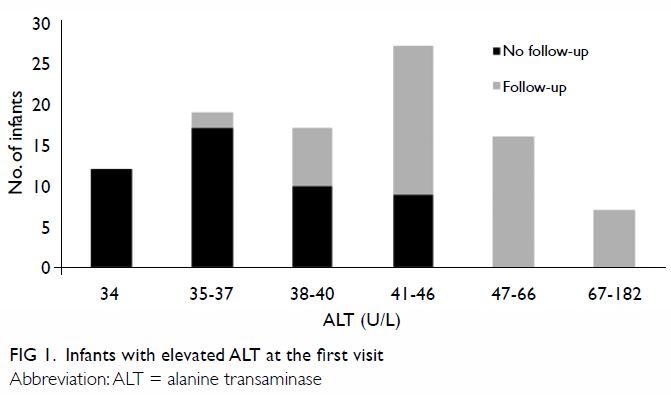

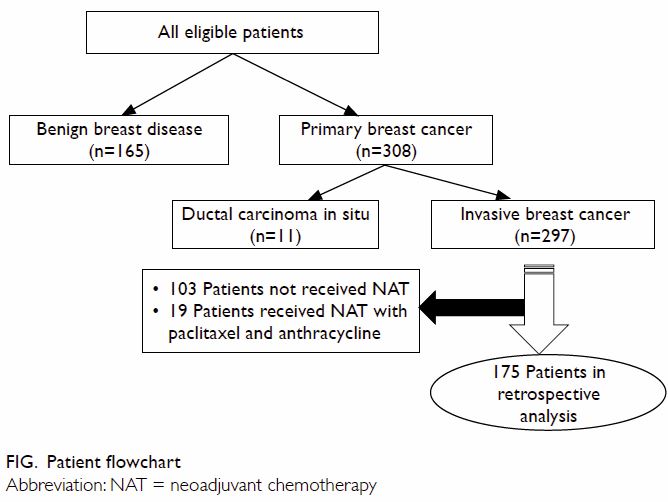

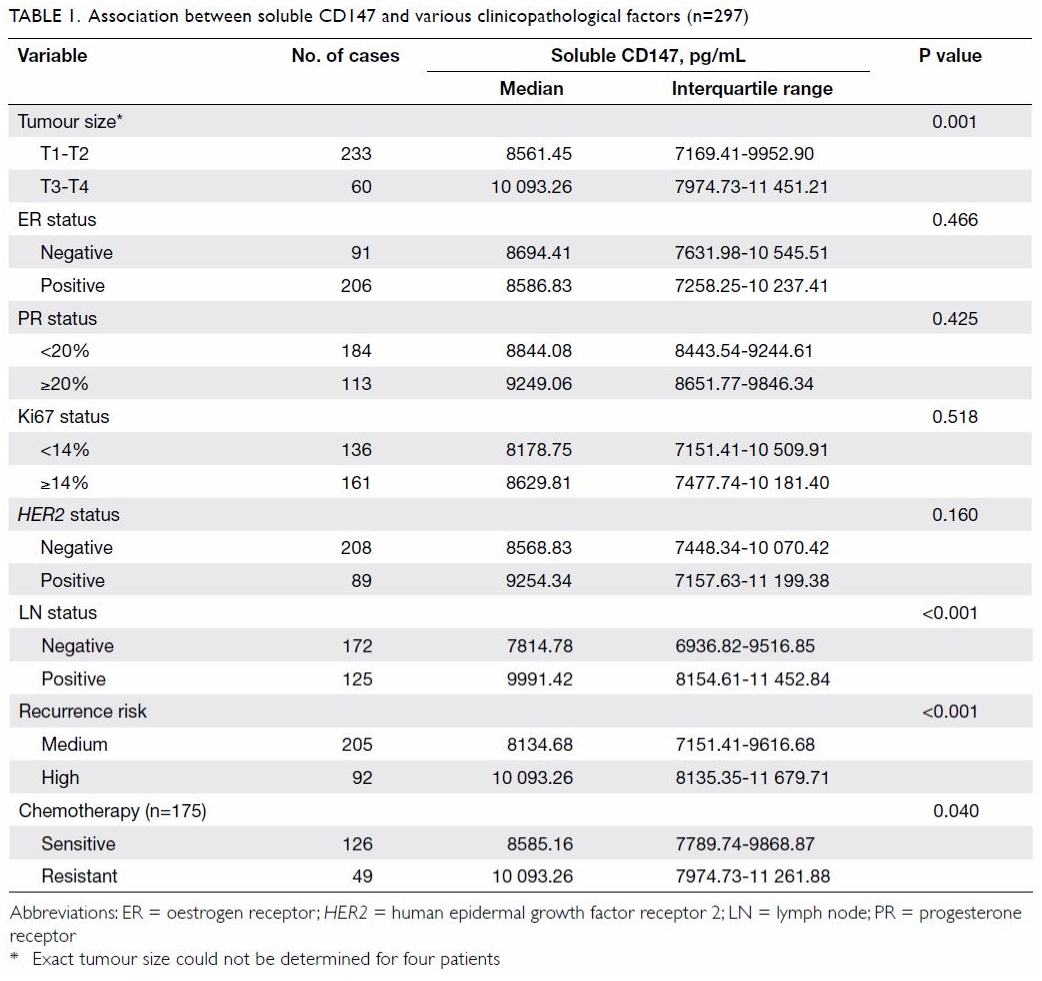

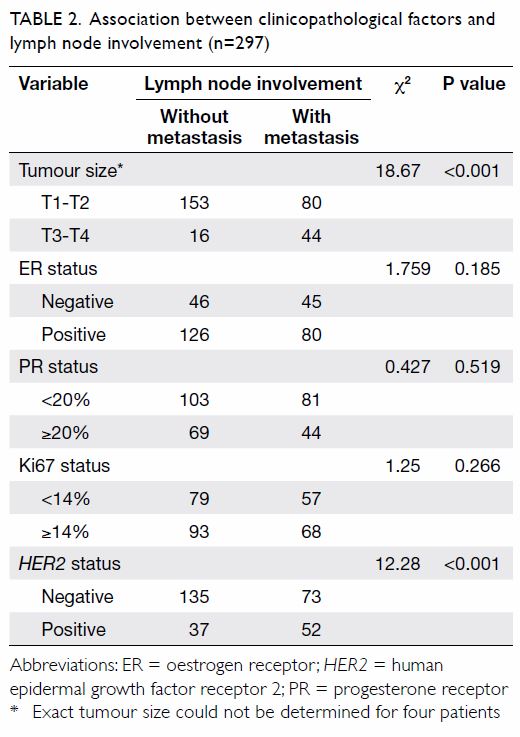

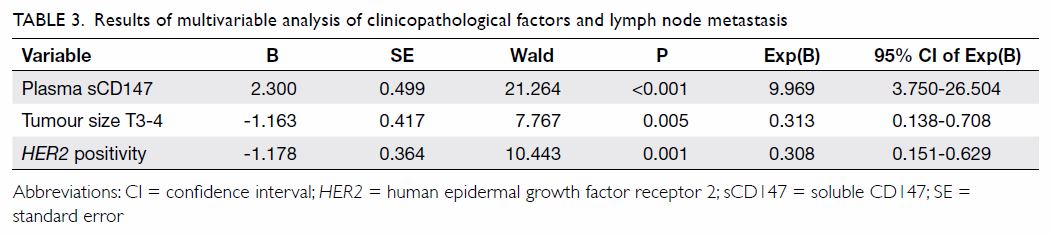

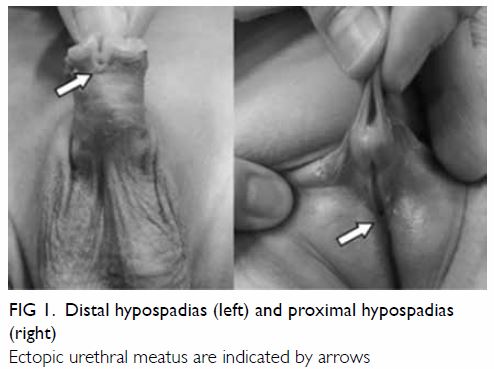

monitoring, and cost-benefit analysis (Fig 1).

Pilot study to investigate the feasibility of the

10-step OPathPaed model

Step 1: Parental education

Educational talks were delivered by chemical

pathologists during antenatal visits. With the help of the Save Babies

Through Screening Foundation, we added Chinese subtitles to the video

titled “Newborn Screening Saves Babies One Foot at a Time”. The video is

available online (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxFit_a601w).

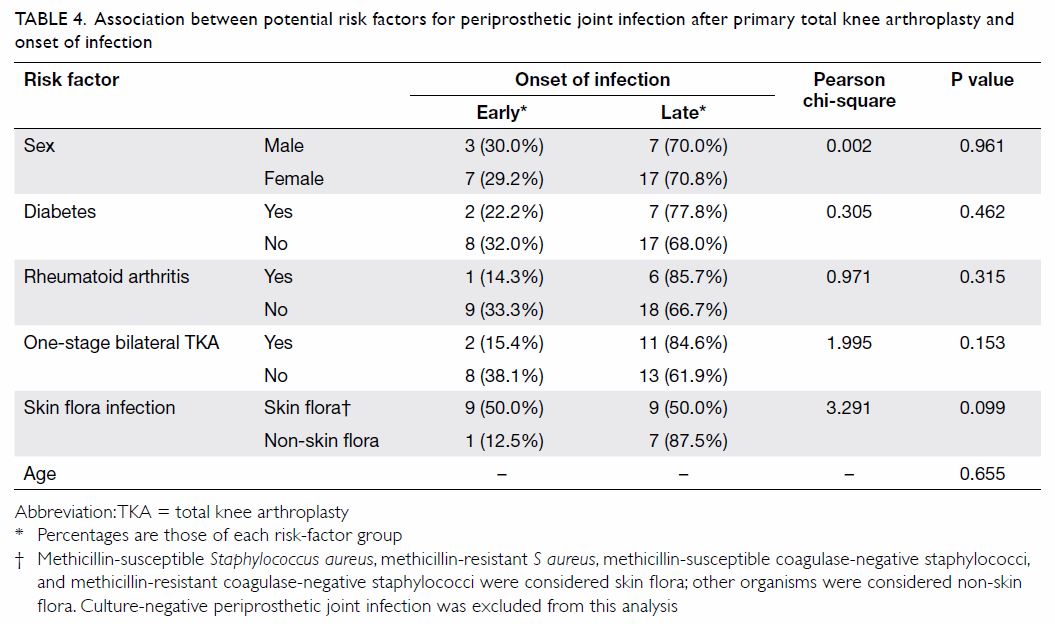

DVDs and a locally designed pamphlet with an email address and telephone

number for enquiries were distributed to expectant mothers (Fig

2). In order to raise public awareness, several interviews with the

media were arranged and reports were published in several newspapers20 21 22 and radio and television programmes.23 24

Figure 2. Chinese version of pilot study pamphlet on newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism

Step 2: Obtaining consent

A consent form was designed for NBS for IEM (data

not shown). Educational videos and pamphlets were used to inform the

parents. Written informed consent was collected during a postnatal talk

after the education session. The talk was conducted in group presentation

for the mothers by chemical pathologists.

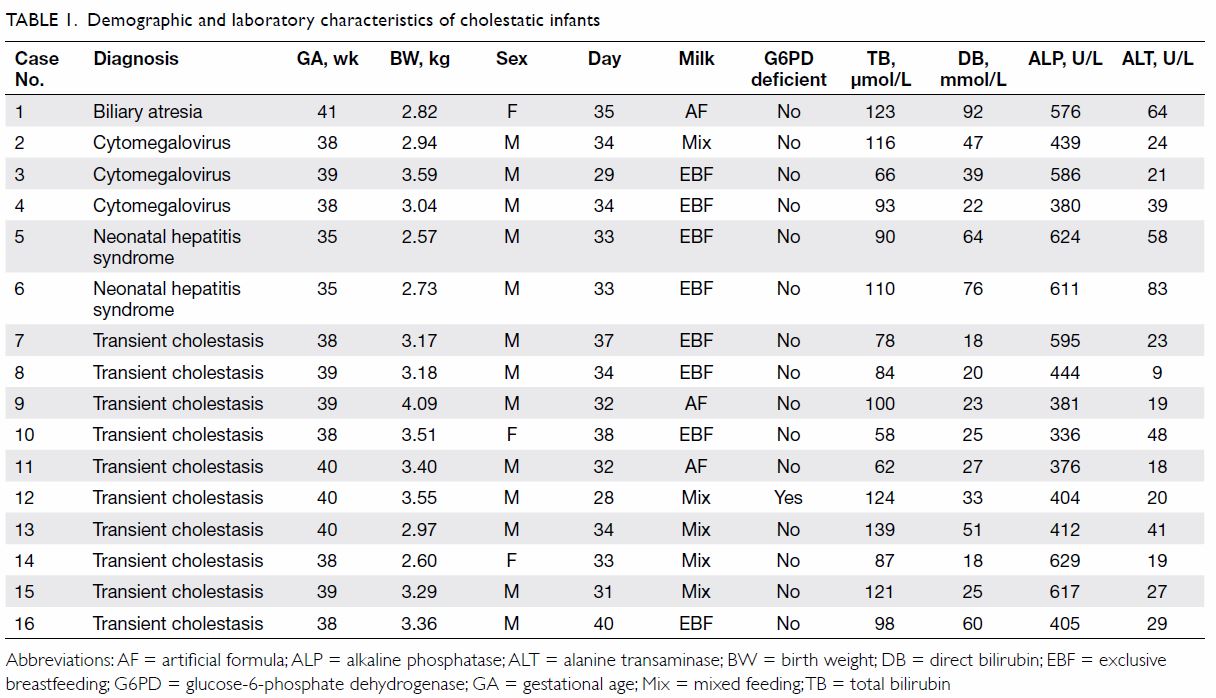

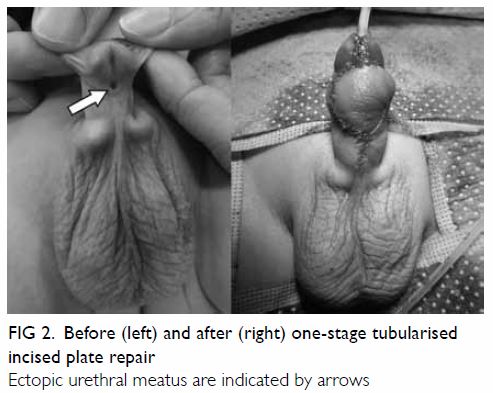

Step 3: Sampling

Paediatricians or pathologists organised training

for phlebotomists on the heel prick technique, in compliance with the

Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute guidelines.25 An instruction sheet with photographs of valid and

invalid DBS samples was provided as guidance for the phlebotomists (Fig

3). Samples were collected from neonates aged between 24 hours and

28 days.

Step 4: Dried blood spot dispatching

Drying racks and special boxes designed for

specimen transport before complete drying were delivered to the testing

sites. Complete drying of blood spots was ensured for valid sample

integrity. The blood spot cards were dried perpendicular to each other

above and below the rack position to avoid contact contamination between

blood spots of different patients.

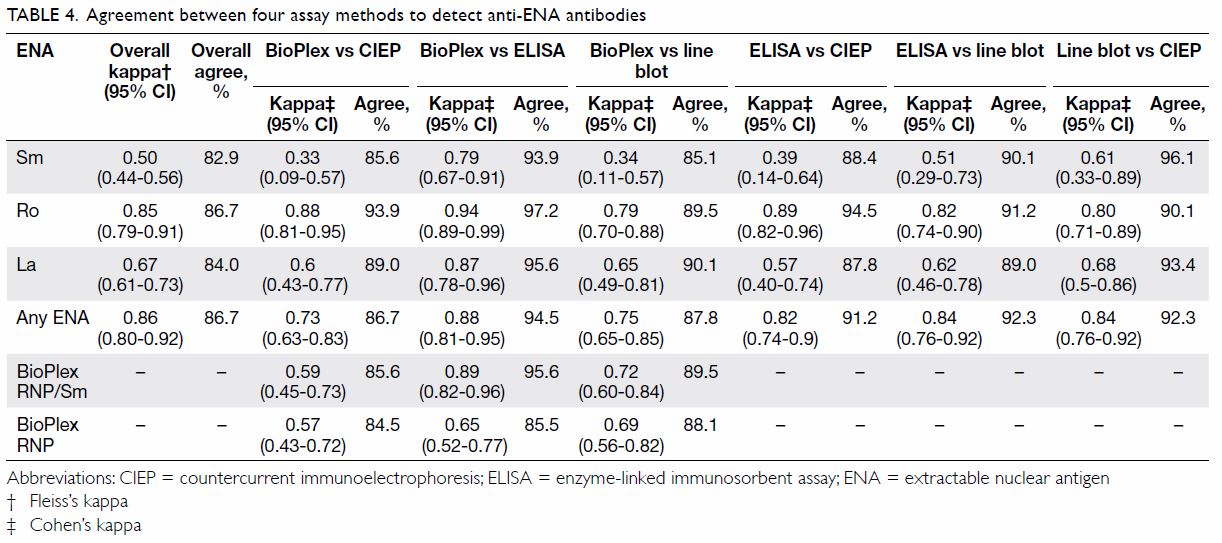

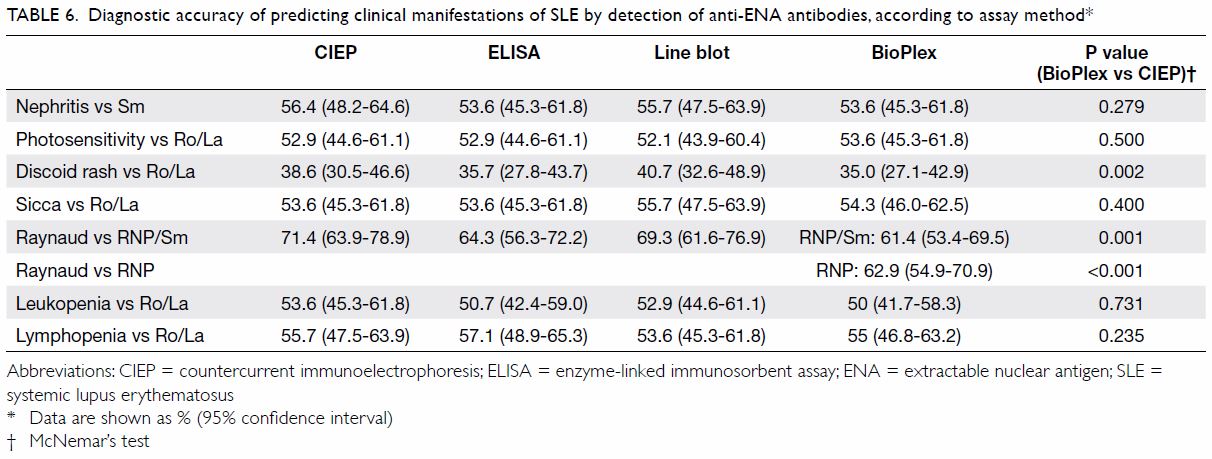

Step 5: Dried blood spot preparation and testing

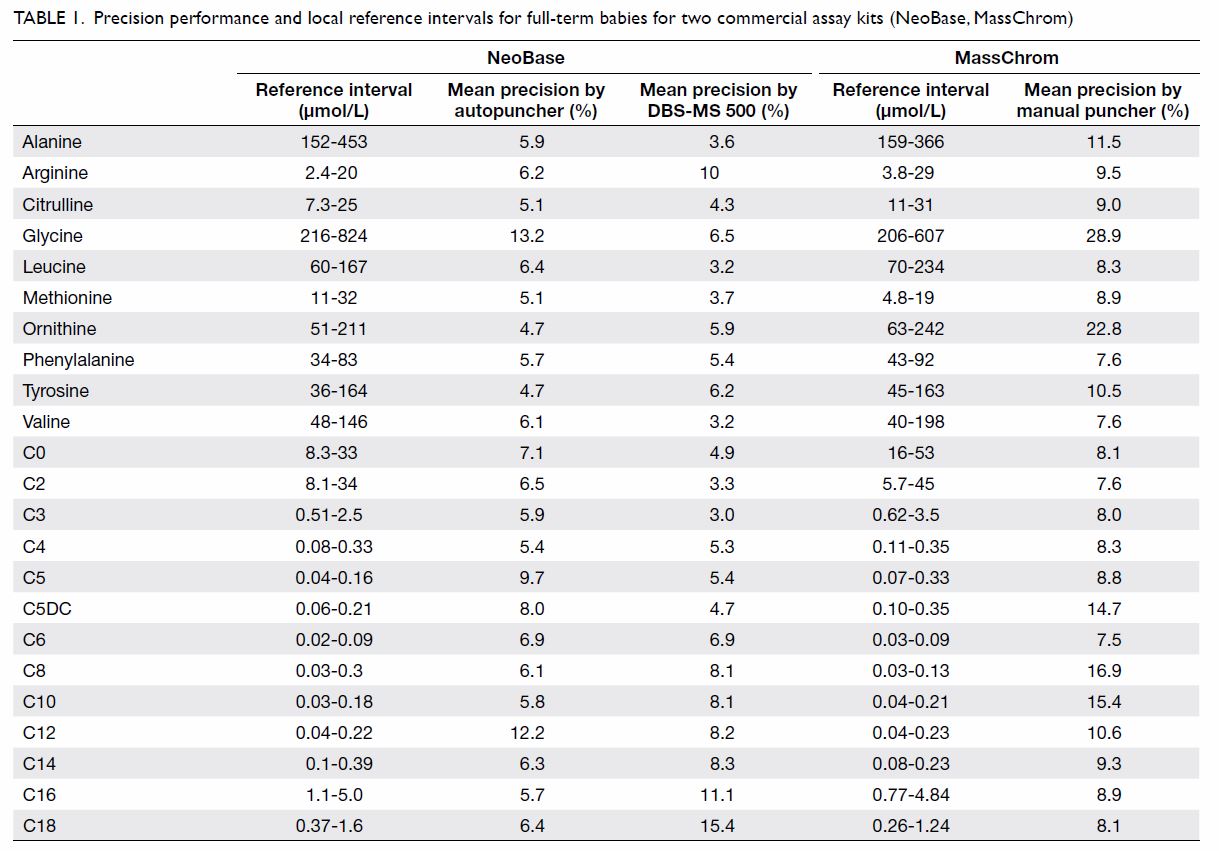

Two commercial DBS assay kits: (1) MassChrom Amino

Acids and Acylcarnitines from Dried Blood/Non-derivatised (Chromsystems

Instruments & Chemicals GmBH, Gräfelfing, Germany); and (2) NeoBase

Non-derivatized MSMS kit (with succinylacetone assay; PerkinElmer, Waltham

[MA], US) were validated for use in the study. In addition to a manual

puncher and an autopuncher for DBS preparation, a fully automated online

extraction system (DBS-MS 500; CAMAG, Muttenz, Switzerland) was also

evaluated. The precision and local reference intervals of the commercial

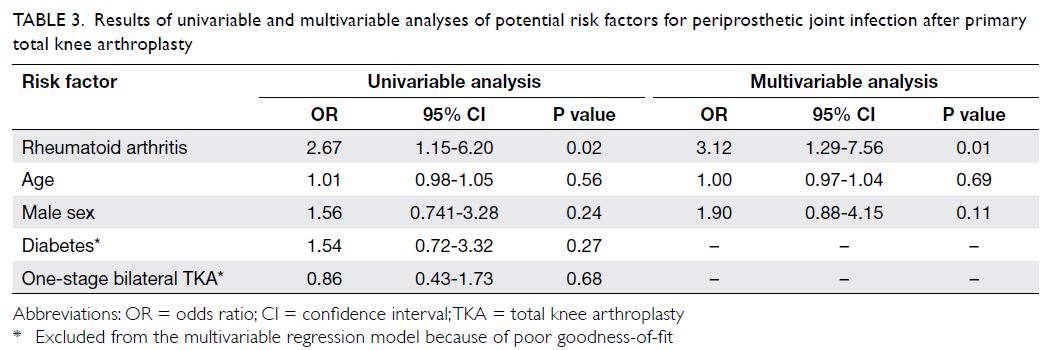

assay kits are listed in Table 1. Our laboratory has participated in the

Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Programme organised by the US Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 2011. The disease panel

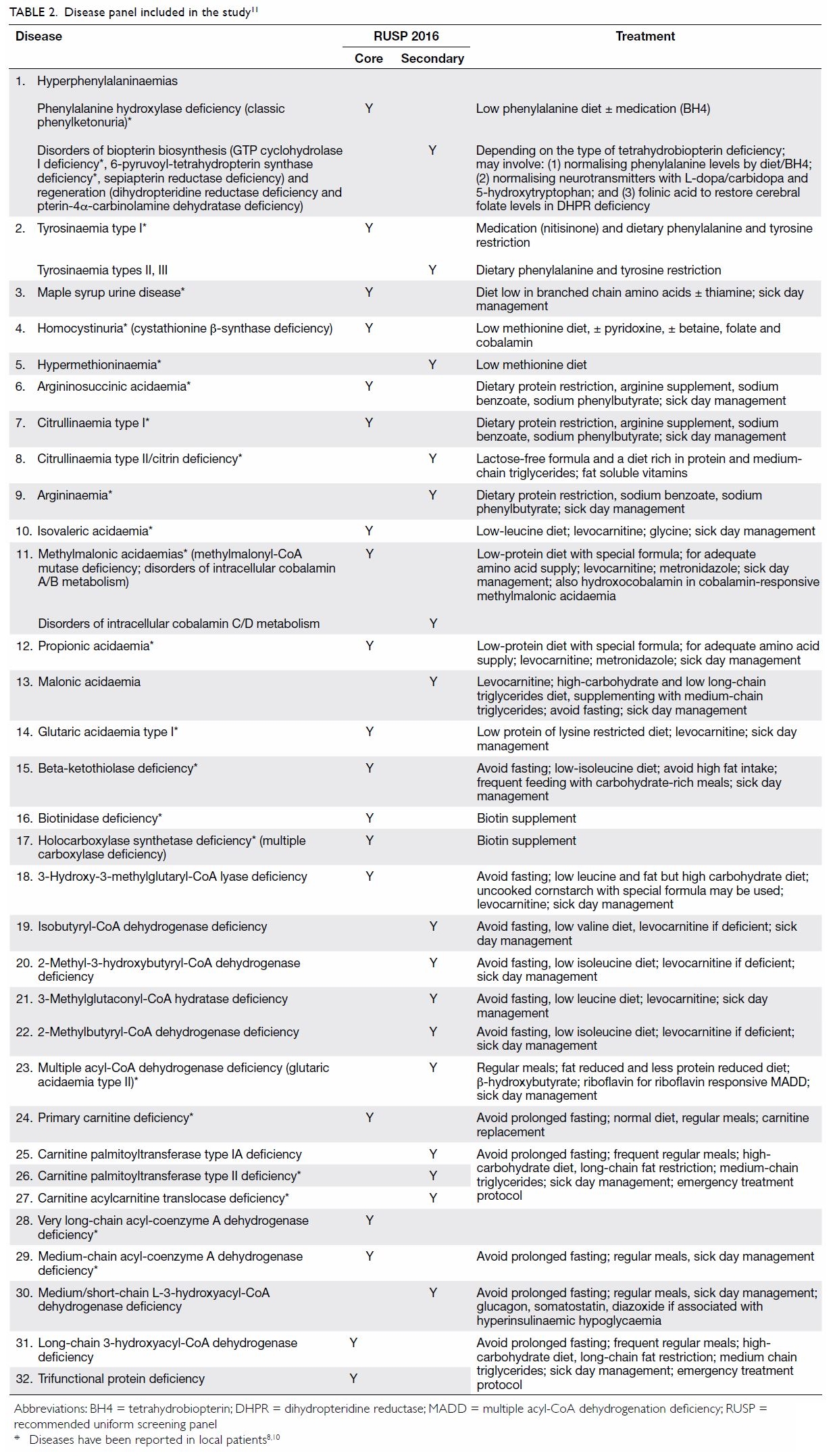

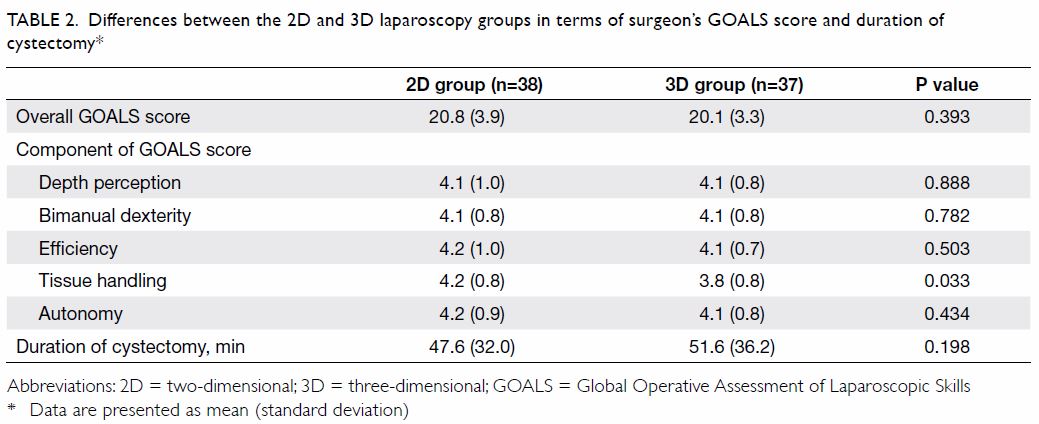

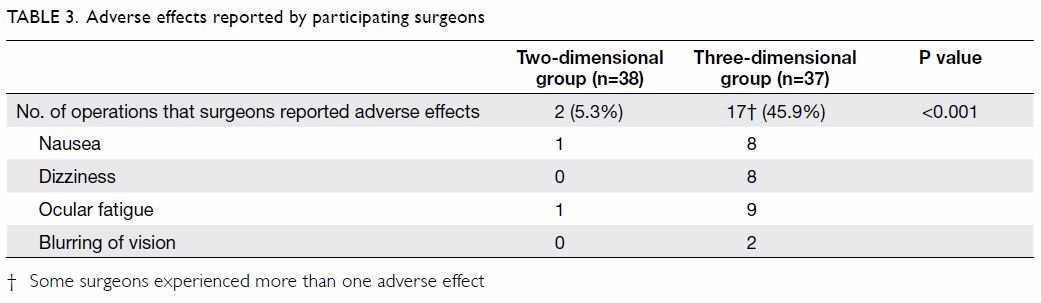

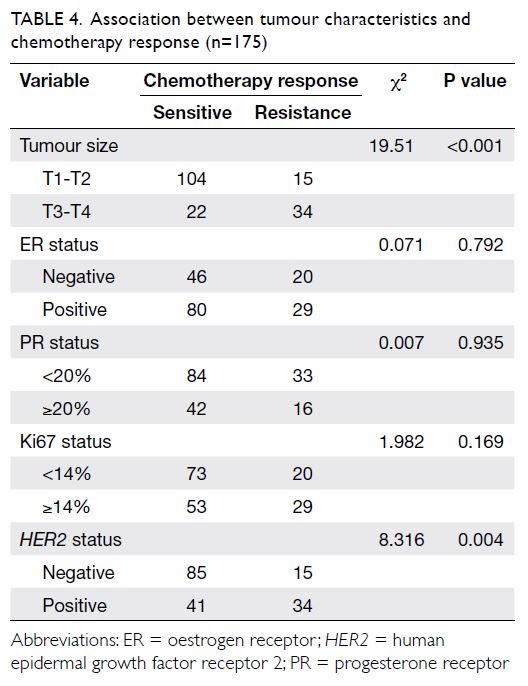

included in the study is shown in Table 2.8 10 11

Table 1. Precision performance and local reference intervals for full-term babies for two commercial assay kits (NeoBase, MassChrom)

Step 6: Reporting

Chemical pathologists were responsible for

reporting of positive results to the paediatricians. The CDC cut-off for

clinical decision (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NSQAP/Restricted/CDCCutOffs.aspx)

and the Region 4 Stork Collaborative Project (https://www.clir-r4s.org/)

data interpretation tools were applied during interpretation of the

results.

Step 7: Recall and counselling

Newborn Screening ACT Sheets and Confirmatory

Algorithms by the American College of Medical Genetics (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55827/)

were followed for patient recall. All abnormal results were examined by

chemical pathologists. These chemical pathologists were also responsible

for contacting the parents for post-test counselling and for arranging

subsequent hospital referrals for care by paediatricians.

Step 8: Confirmation test

Confirmation of diagnosis was provided by regional

laboratories through measurements of functional metabolites (mainly plasma

amino acid levels, plasma acylcarnitine levels, and urine organic acid

levels) and genetic diagnosis by DNA sequencing wherever appropriate.

Step 9: Treatment and monitoring

Admission logistics and treatment protocols for

neonatal units with on-call rosters were established by hospital

paediatricians. The same regional laboratories mentioned in Step 8

continued to provide biochemical diagnostic services.

Step 10: Cost-benefit analysis

A cost-benefit analysis has been conducted and

published previously.26

Hyperphenylalaninaemia due to 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase

deficiency was used as an example to evaluate the costs and benefits of

implementing an expanded NBS programme in Hong Kong. Assuming an annual

birth rate of 50 000 and hyperphenylalaninaemia incidence of 1 in 29 542

live births, the annual medical costs and adjusted loss of workforce would

be HK$20 773 207. The implementation and operational costs of an expanded

NBS programme are expected to be HK$10 473 848 annually. Thus,

implementing the expanded NBS programme is expected to result in an annual

saving of HK$9 632 750.26

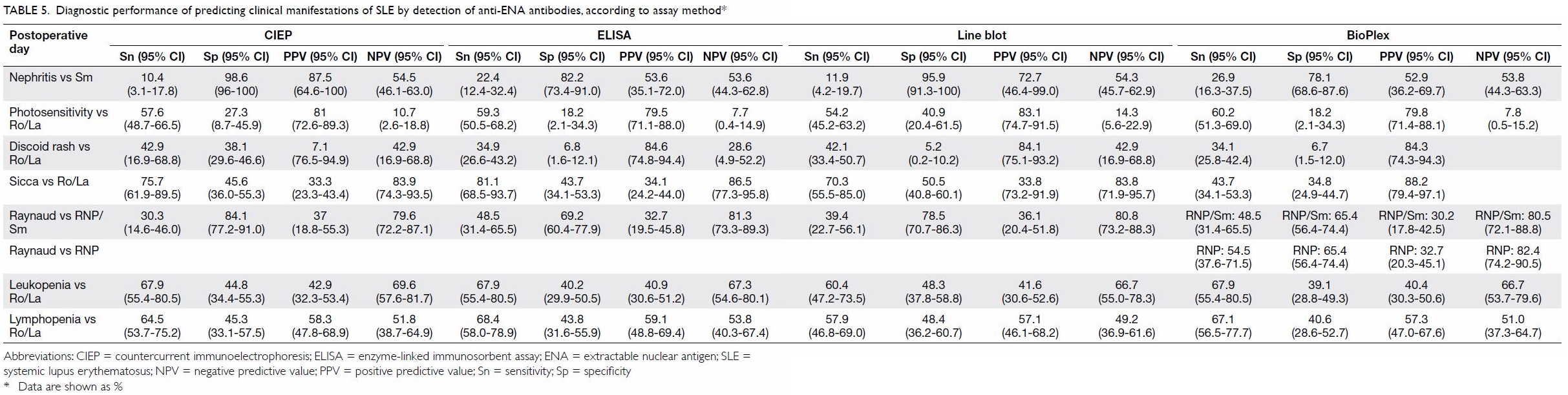

Survey of health care professionals’ knowledge and

opinions of newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism

A questionnaire was distributed by convenience

sampling to 430 health care professionals who worked in hospitals and were

not involved in the pilot study. These self-administered questionnaires

were distributed to local health care professionals including medical

doctors, nurses, and other allied health care professionals either in

person with returning envelopes or via email to department heads for

further distribution. The self-administered questionnaire in English was

modified from a previously published questionnaire that was tested among

parents.27 The self-administered

questionnaire included 13 questions that covered the local practice of the

existing NBS programme, as well as knowledge and opinions of an expanded

NBS programme. No personal identifiers were included in the questionnaire

and questions were mostly in a closed-ended format. Data analyses were

performed using Excel 2000 (Microsoft Corp. Redmond [WA], US) and GraphPad

QuickCalcs (http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ConfInterval1.cfm).

Percentages for each question were calculated as the number of replies

divided by the total number of respondents for that question. The

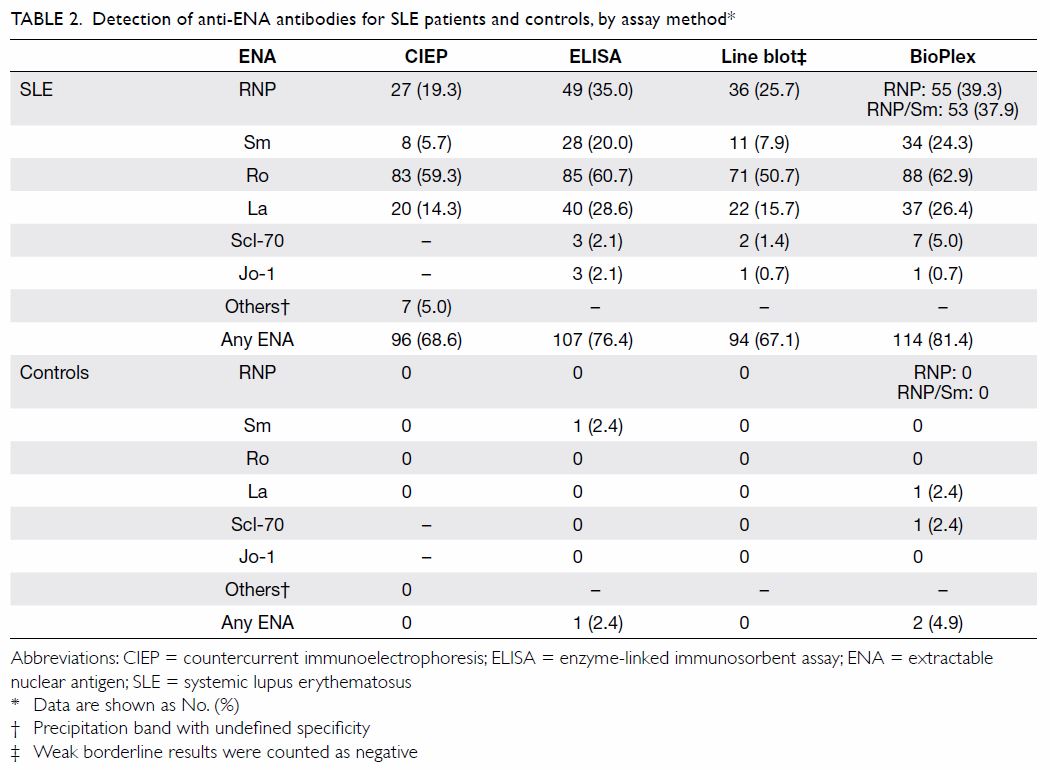

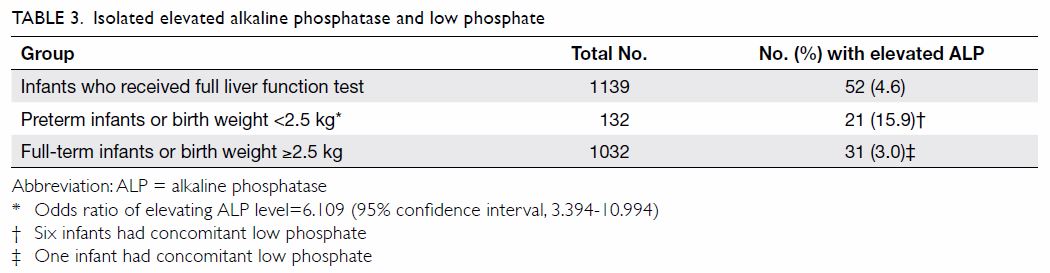

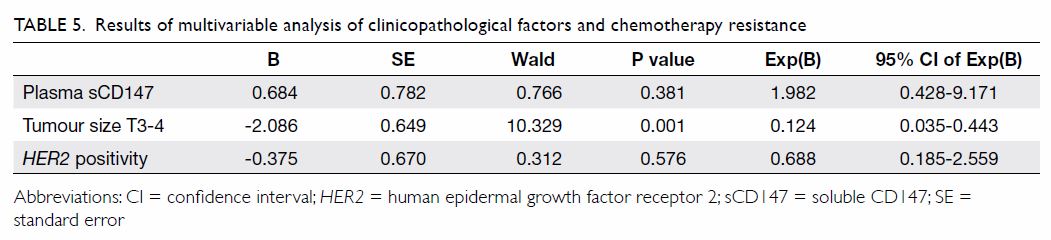

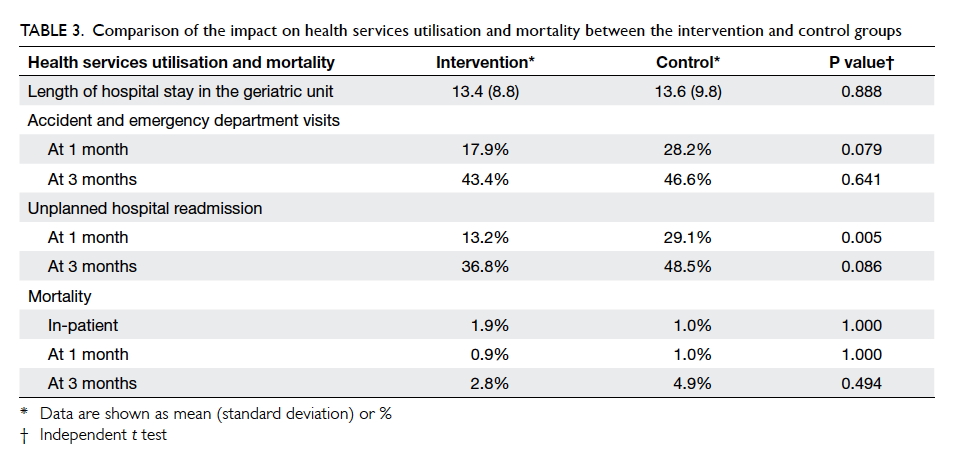

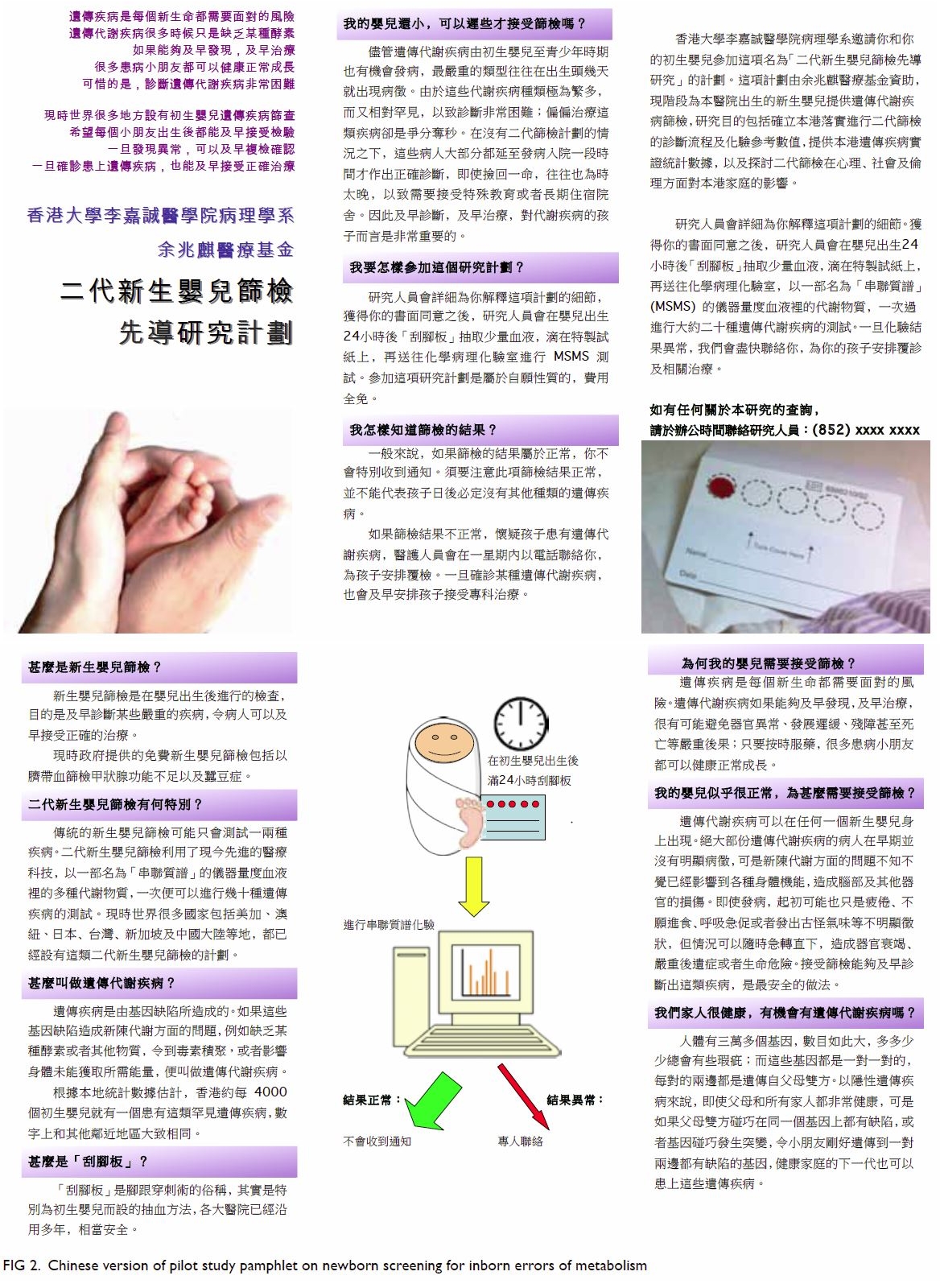

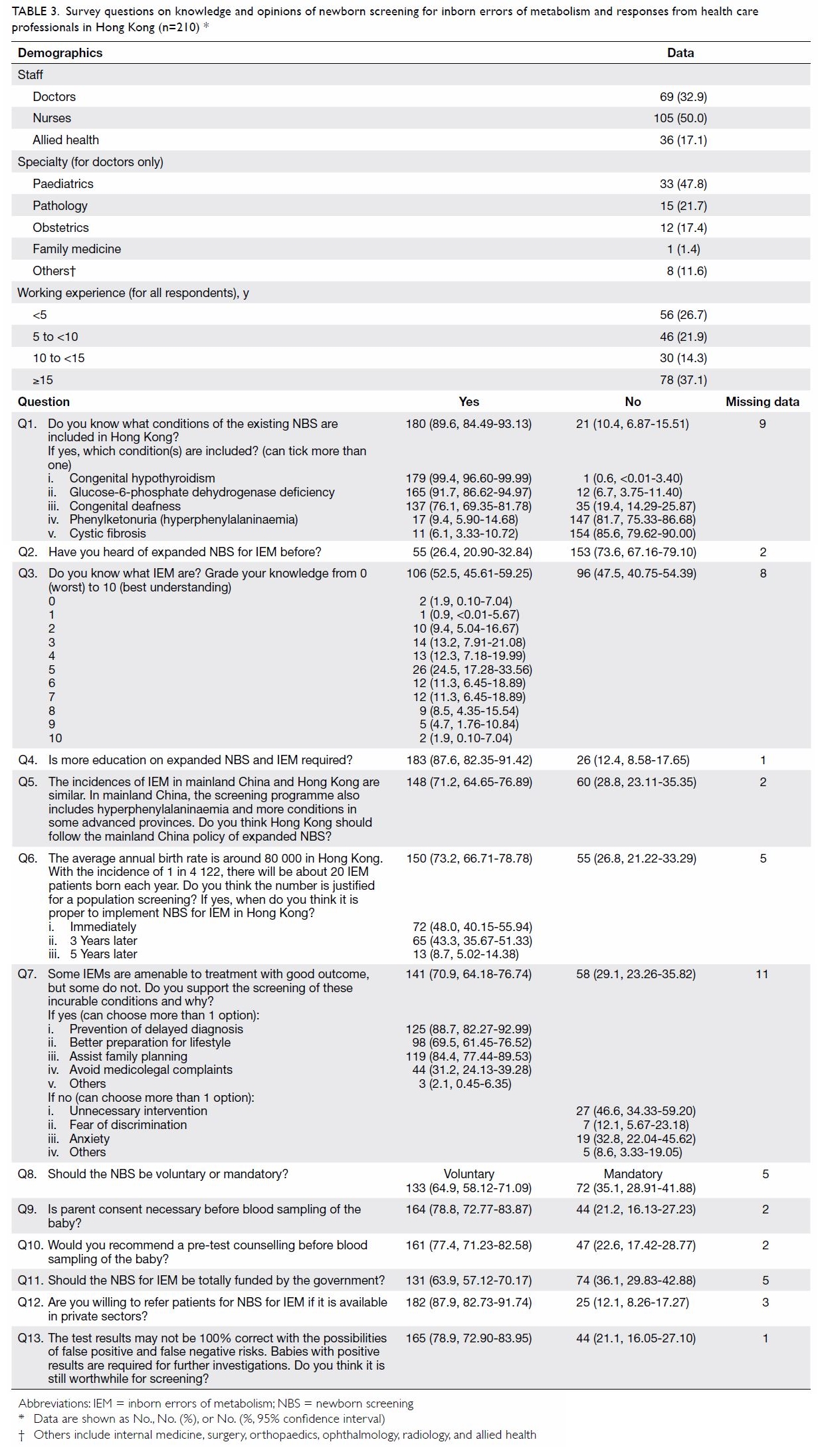

questions and corresponding responses are shown in Table 3.

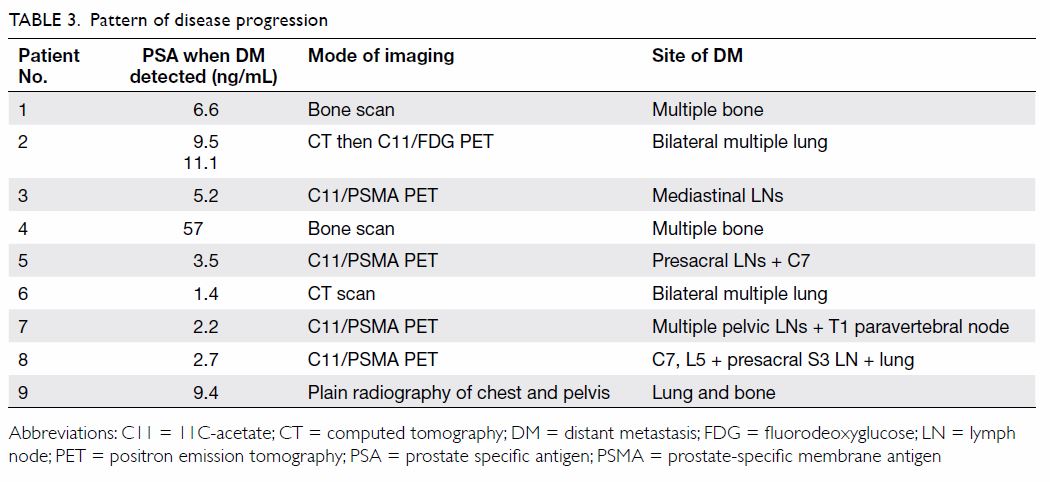

Table 3. Survey questions on knowledge and opinions of newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism and responses from health care professionals in Hong Kong (n=210)

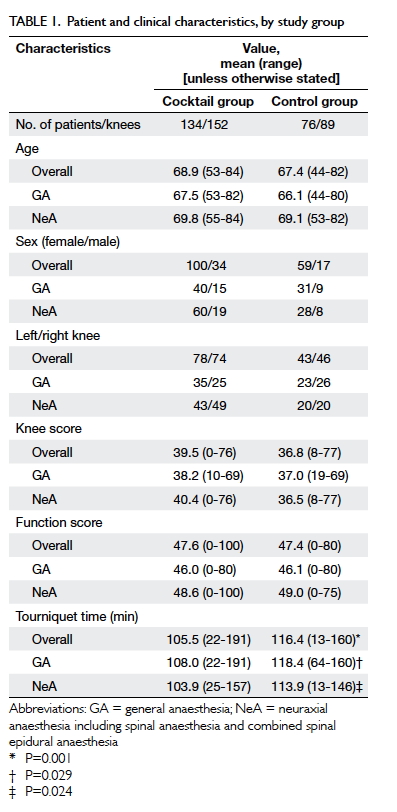

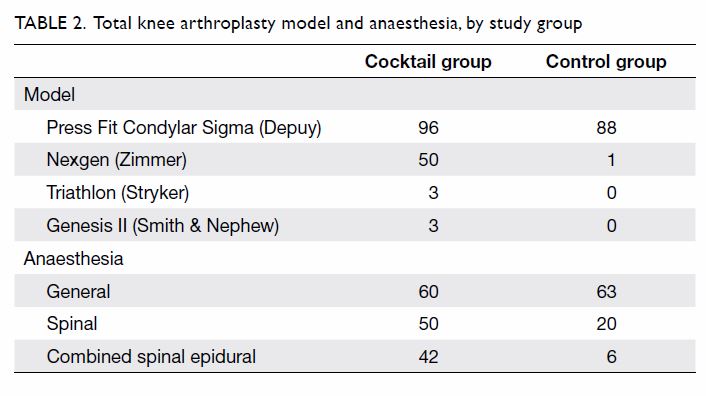

Results

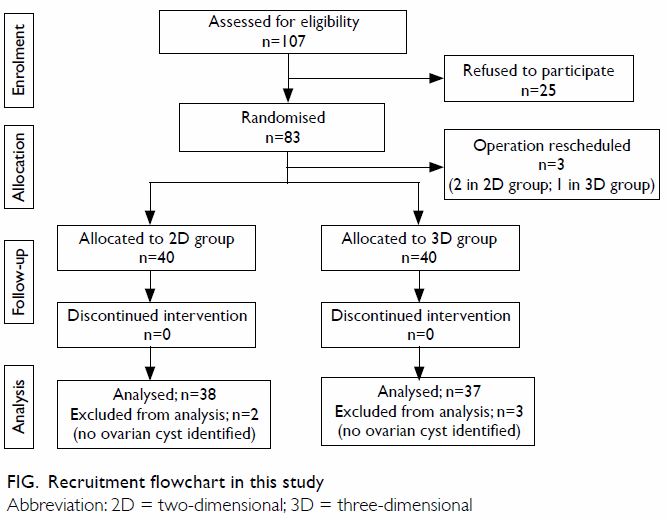

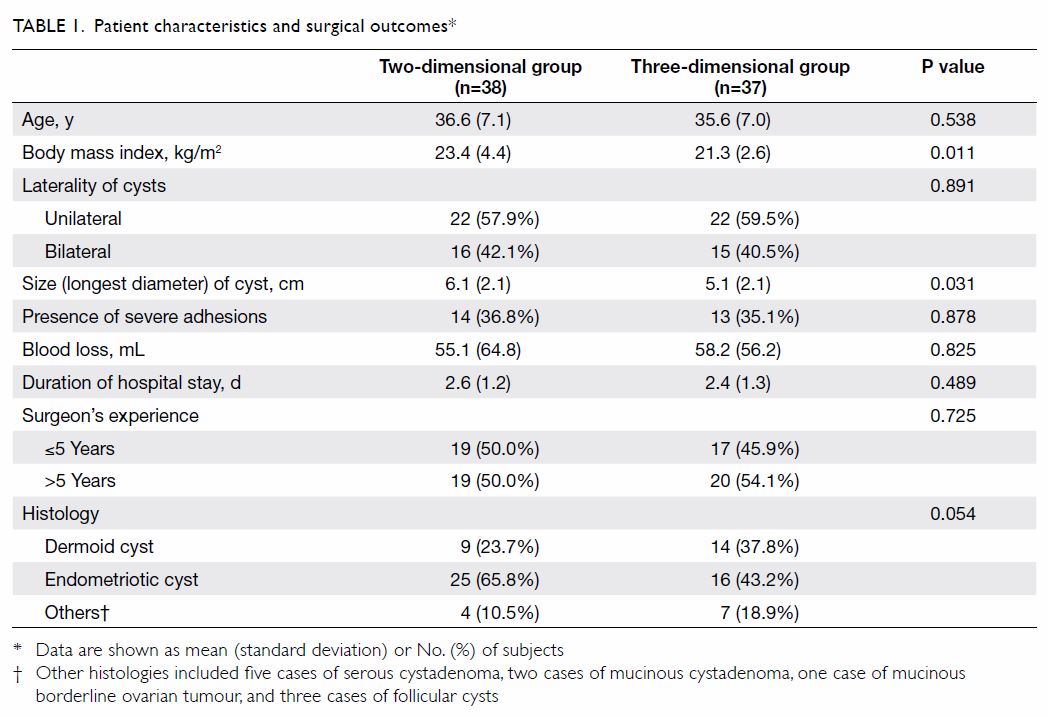

Pilot study recruitment

By 31 August 2014, 2440 neonates had been

recruited. The DBSs were collected from neonates aged 24 to 48 hours

(n=2064, 84.6%), 3 to 5 days (n=331, 13.6%), 5 to 7 days (n=9, 0.4%), and

7 to 28 days (n=36, 1.5%). The participation rate was 86.6% on the days

when blood samples were collected. There were no recorded DBS sampling or

dispatch failures. The method validation and results of the DBS amino

acids and acylcarnitine assays have been published elsewhere28; further details are available from the corresponding

author on request. Overall, no true-positive cases were found in this

pilot study, likely because of the limited sample size. Six (0.25%)

false-positive cases were detected in 2440 neonates; of these, two had

mild elevations in long-chain acylcarnitine levels, two had high tyrosine

levels, one had a high citrulline level, and one had a low free carnitine

level. Subsequent laboratory findings were all normal. No false-negative

cases were reported from the IEM clinics of the involved hospitals within

2 years after project completion. However, patients who emigrated or

received treatment at private institutions could not be followed up.

Health care professionals’ knowledge and opinions of

newborn screening for inborn errors of metabolism

A total of 430 questionnaires were distributed and

210 (48.8%) completed responses were received. Results are shown in Table

3. Of the respondents, 50.0% were nurses and 32.9% were doctors. The

doctors worked mainly in departments of paediatrics (47.8%), pathology

(21.7%), and obstetrics (17.4%). Most (89.6%) respondents were aware of

the existing NBS programme for hypothyroidism and G6PD deficiency;

however, 47.5% did not know about IEM and 73.6% had not heard of expanded

NBS for IEM. Most (87.6%) respondents agreed that more education on IEM

and NBS is needed.

Discussion

This is the first prospective pilot study on NBS

for IEM in Hong Kong, and it has successfully evaluated the feasibility of

the OPathPaed model. This study is also the first to investigate the

knowledge and opinions on NBS for IEM of local health care professionals.

To implement an expanded NBS programme for IEM

successfully in Hong Kong, there are several important points that need to

be addressed. First, awareness and knowledge of NBS for IEM among the

general public and among health care professionals should be improved.27 Second, comprehensive data on the local disease

spectrum and incidence should be made available; such data were not

available until recently.3 5 Third, free flow of information and sharing of

experiences among colleagues working in the acute care and public health

sectors should be facilitated. Fourth, more emphasis should be given to

regular updates on NBS health care policy, confirmatory investigation

service support, and treatment protocols. Last, the use of umbilical cord

blood samples in the existing programme is unsuitable for an expanded NBS

programme for IEM because of unacceptably high false-negative rates.29 The metabolites associated with many amino acid

disorders, organic acid disorders, and fatty acid oxidation disorders are

not elevated in cord blood. In 2013, the hospital-based OPathPaed model

was published for the implementation of an expanded NBS programme suitable

for a local setting.19 The present

study further confirms the feasibility of the OPathPaed model for use on a

larger scale. The OPathPaed model integrates expert input from

obstetricians, pathologists, and paediatricians. Because babies born in

Hong Kong are normally delivered in hospitals, the OPathPaed model

approach should be able to achieve full coverage.

The success of an expanded NBS programme for IEM

would depend not only on the diagnostics but also on how well patients

diagnosed with IEM could be managed. It is difficult to accumulate

experience and the many metabolic diseases can easily cause confusion. In

addition, sophisticated management requires individualised drug

formulations, which may not be easily accessible or may involve off-label

prescriptions. Overseas studies have identified significant knowledge gaps

among clinicians involved in the follow-up care of newborns with IEM

identified by NBS.15 16 17 18 Some were poorly prepared to follow up the initial

diagnosis, provide appropriate counselling, or make appropriate clinical

referrals.17 In our study, 73.6%

of 210 health care professionals (who were not involved in the pilot

study) were unaware of the expanded NBS programme, and 47.5% of

respondents did not know what IEM were. The majority of respondents

(87.6%) agreed that better education was needed and 91.3% supported

expanding NBS for IEM immediately or within 3 years. According to a

parental survey among 172 parents regarding NBS for IEM,27 over 89% had never heard of NBS for IEM or metabolic

disorders. Although some IEM may be incurable, 97% of parents supported an

expanded NBS programme and 82.8% of parents supported implementation of

this expansion immediately or within 3 years.27

The present study also provides the first local

evaluation of the fully automated DBS-MS 500 system. The DBS is directly

eluted into the extraction chamber, with an online extraction system

connecting with the tandem mass spectrometer. There is no need for DBS

card punching. Together with the integrated optical card recognition and

barcode reading module, this automation minimises the risk of sample

misidentification during manual processing. The precision and accuracy

demonstrated are comparable to those of conventional procedures. However,

because the DBS-MS 500 system requires application of an internal standard

solution before extraction, the financial cost per extraction would be

higher than that for conventional methods. In addition, special DBS cards

are required for the extraction chamber. Third-party DBS cards of a

specific quality may not easily fit into the system. The throughput of up

to 500 DBS cards per run is more than adequate for local needs, as there

are about 50 000 live births annually in Hong Kong.

The limitations of the pilot study include small

and non-representative sample size, a relatively short study period that

may have been inadequate for follow-up to confirm true negatives, and the

convenience sampling and low response rate of the health care professional

survey.

Conclusion

The present pilot study investigated the

feasibility of an expanded NBS for IEM in Hong Kong, and surveyed health

care professionals for their knowledge and opinions on NBS for IEM. We

successfully evaluated the OPathPaed model on a larger scale than has been

attempted previously and demonstrated that health care professionals have

a favourable opinion of implementing an expanded NBS programme in Hong

Kong. It is timely that, as this pilot study was completed, the needs of

parents and health care workers were addressed in the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region Chief Executive’s Policy Address of 2015, when a

government-led initiative was announced to study the feasibility of NBS

for IEM in the public health care system on a large scale.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept or design of this study; acquisition of data; analysis or

interpretation of data; drafting of the article; and critical revision for

important intellectual content.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge all collaborators, doctors, nurses,

medical technologists, phlebotomists, information technologists, and

parents for their efforts and support. We thank the Save Babies Through

Screening Foundation for allowing us to use their video for educational

purpose. We thank CAMAG Germany for providing technical support during the

evaluation of the DBS-MS 500. The CAMAG had no role in the study design,

data collection, analysis, reporting, or manuscript preparation.

Funding/support

This work was funded by the SK Yee Medical

Foundation. The funder had no role in study design, data collection,

analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Declaration

All authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity.

Ethical approval

Local ethical approval was obtained from each of

the regional hospitals involved in this study.

References

1. Millington DS, Kodo N, Norwood DL, Roe

CR. Tandem mass spectrometry: a new method for acylcarnitine profiling

with potential for neonatal screening for inborn errors of metabolism. J

Inherit Metab Dis 1990;13:321-4. Crossref

2. Carpenter KH, Wiley V. Application of

tandem mass spectrometry to biochemical genetics and newborn screening.

Clin Chim Acta 2002;322:1-10. Crossref

3. Lee HC, Mak CM, Lam CW, et al. Analysis

of inborn errors of metabolism: disease spectrum for expanded newborn

screening in Hong Kong. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124:983-9.

4. Davies DP. Hong Kong Reflections:

Health, Illness and Disability in Hong Kong Children. Hong Kong: The

Chinese University Press; 1995.

5. Hui J, Tang NL, Li CK, et al. Inherited

metabolic diseases in the Southern Chinese population: spectrum of

diseases and estimated incidence from recurrent mutations. Pathology

2014;46:375-82. Crossref

6. Gu X, Wang Z, Ye J, Han L, Qiu W.

Newborn screening in China: phenylketonuria, congenital hypothyroidism and

expanded screening. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2008;37(12 Suppl):107-10.

7. Niu DM, Chien YH, Chiang CC, et al.

Nationwide survey of extended newborn screening by tandem mass

spectrometry in Taiwan. J Inherit Metab Dis 2010;33(Suppl 2):S295-305. Crossref

8. Chace DH, Kalas TA, Naylor EW. The

application of tandem mass spectrometry to neonatal screening for

inherited disorders of intermediary metabolism. Annu Rev Genomics Hum

Genet 2002;3:17-45. Crossref

9. Zheng S, Song M, Wu L, et al. China:

public health genomics. Public Health Genomics 2010;13:269-75. Crossref

10. American College of Medical Genetics

Newborn Screening Expert Group. Newborn screening: toward a uniform

screening panel and system—executive summary. Pediatrics 2006;117(5 Pt

2):S296-307. Crossref

11. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel,

The Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, US

Department of Health and Human Services. Available from:

https://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/mchbadvisory/heritabledisorders/recommendedpanel/.

Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

12. Therrell BL, Johnson A, Williams D.

Status of newborn screening programs in the United States. Pediatrics

2006;117(5 Pt 2):S212-52. Crossref

13. Lee HC, Lai CK, Siu TS, et al. Role of

postmortem genetic testing demonstrated in a case of glutaric aciduria

type II. Diagn Mol Pathol 2010;19:184-6. Crossref

14. Coroners’ Report 2008. Available from:

http://www.judiciary.hk/en/publications/coroner_report_july08.pdf.

Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

15. Gennaccaro M, Waisbren SE, Marsden D.

The knowledge gap in expanded newborn screening: survey results from

paediatricians in Massachusetts. J Inherit Metab Dis 2005;28:819-24. Crossref

16. Wells AS, Northrup H, Crandell SS, et

al. Expanded newborn screening in Texas: a survey and educational module

addressing the knowledge of pediatric residents. Genet Med 2009;11:163-8.

Crossref

17. Kemper AR, Uren RL, Moseley KL, Clark

SJ. Primary care physicians’ attitudes regarding follow-up care for

children with positive newborn screening results. Pediatrics

2006;118:1836-41. Crossref

18. Dunn L, Gordon K, Sein J, Ross K.

Universal newborn screening: knowledge, attitudes, and satisfaction among

public health professionals. South Med J 2012;105:218-22. Crossref

19. Mak CM, Lam C, Siu W, et al. OPathPaed

service model for expanded newborn screening in Hong Kong SAR, China. Br J

Biomed Sci 2013;70:84-8. Crossref

20. 一滴血驗出罕見遺傳病. Oriental Daily 2010 Sep

12. Available from:

http://orientaldaily.on.cc/cnt/news/20100912/00176_002.html. Accessed 1

Aug 2017.

21. 二代新生嬰兒篩檢代謝疾病. am730 2013 May 6.

Available from: http://archive.am730.com.hk/column-153216. Accessed 1 Aug

2017.

22. 篩查防智障代謝病, 社會可年省近千萬. Ming Pao 2014 Jun

9. Available from: https://news.mingpao.com/pns/篩查防智障代謝病%20社會可年省近千萬/web_tc/article/20140609/s00002/1402257010439. Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

23. 精靈一點 (RTHK radio programme, 2014 Apr

15). Available from:

http://programme.rthk.hk/channel/radio/programme.php?name=radio1/adwiser&d=2014-04-15&p=1147&e=259149&m=episode.

Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

24. 星期二檔案:這幾滴血 (TVB programme, 2014 Feb

25). Available from:

http://programme.tvb.com/news/tuesdayreport/episode/20140225/#page-1.

Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

25. NBS01-A6, Blood Collection on Filter

Paper for Newborn Screening Programs; Approved Standard—Sixth Edition.

Available from:

https://clsi.org/standards/products/newborn-screening/documents/nbs01/.

Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

26. Lee HH, Mak CM, Poon GW, Wong KY, Lam

CW. Cost-benefit analysis of hyperphenylalaninemia due to

6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase (PTPS) deficiency: for consideration

of expanded newborn screening in Hong Kong. J Med Screen 2014;21:61-70. Crossref

27. Mak CM, Lam CW, Law CY, et al.

Parental attitudes on expanded newborn screening in Hong Kong. Public

Health 2012;126:954-9. Crossref

28. Mak M. Chemical pathology analysis of

inborn errors of metabolism for expanded newborn screening in Hong Kong

[thesis]. The University of Hong Kong; 2012. Available from:

http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/180075. Accessed 1 Aug 2017.

29. Walter JH, Patterson A, Till J, Besley

GT, Fleming G, Henderson MJ. Bloodspot acylcarnitine and amino acid

analysis in cord blood samples: efficacy and reference data from a large

cohort study. J Inherit Metab Dis 2009;32:95-101. Crossref