Hong

Kong Med J 2017 Dec;23(6):599–608 | Epub 10 Nov 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166138

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Frameless stereotactic radiosurgery for brain

metastases: a review of outcomes and prognostic scores evaluation

ST Mok, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Michael KM Kam, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1; WK Tsang, FHKCR,

FHKAM (Radiology)1; Darren MC Poon, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Herbert H Loong, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; WM Yeung, FHKCR,

FHKAM (Radiology)1; TY Yeung, FHKCR, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Jimmy Yu, BSc (Hons), MPhil1; Carlos KH Wong, PhD3

1 Department of Clinical Oncology,

Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Clinical Oncology,

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

3 Department of Family Medicine and

Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

This paper was presented at the MASCC/ISOO

meeting 2016, 23-25 June 2016, Adelaide, Australia.

Corresponding author: Dr ST Mok (mst216@ha.org.hk)

A video clip showing frameless

stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases is available at www.hkmj.org

A video clip showing frameless

stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases is available at www.hkmj.orgAbstract

Introduction: Stereotactic brain

radiosurgery provides good local control in patients with limited brain

metastases. A newly developed frameless system allows pain-free

treatment. We reviewed the effectiveness of this frameless stereotactic

brain radiosurgery and identified prognostic factors that may aid better

patient selection.

Methods: Medical records of

patients with brain metastases treated with linear accelerator–based

frameless stereotactic brain radiosurgery between January 2010 and July

2015 in a university affiliated hospital in Hong Kong were reviewed.

Outcomes including local and distant brain control rate,

progression-free survival, and overall survival were analysed.

Prognostic factors were identified by univariable and multivariable

analyses. Association of outcomes with four common prognostic scores was

performed.

Results: In this study, 64

patients with 94 lesions were treated with a median dose of 18 Gy

(range, 12-22 Gy) in a single fraction. The median follow-up was 11.5

months. One-year actuarial local and distant brain control rates were

72% and 71%, respectively. The median overall survival was 13.0 months.

On multivariable analysis, Karnofsky performance status score (>50 vs

≤50) and number of lesions (1-2 vs ≥3) were found to associate

significantly with distinct brain progression-free survival (P=0.022,

hazard ratio=0.20, 95% confidence interval 0.05-0.80 and P=0.003, hazard

ratio=0.31, 95% confidence interval 0.14-0.68, respectively). Overall

survival was associated significantly with Basic Score for Brain

Metastases (P=0.031), Score Index for Radiosurgery in Brain Metastases

(P=0.007), and Graded Prognostic Assessment (P=0.003). Improvement in

overall survival was observed in all groups of different prognostic

scores.

Conclusion: Frameless

stereotactic brain radiosurgery is effective in patients with

oligo-metastases of brain and should be increasingly considered in

patients with favourable prognostic scoring.

New knowledge added by this study

- Survival of patients with brain metastases has significantly improved over the past decade.

- Frameless stereotactic brain radiosurgery is effective and has acceptable toxicities.

- Calculation of a prognostic score can aid clinicians in the identification of patients who will benefit most from stereotactic brain radiosurgery.

Introduction

Patients with brain metastases have previously had

poor survival of only 3 to 4 months with non-surgical treatment.1 2 Substantial

improvement has been achieved in recent years with the advance of systemic

treatment and radiation techniques. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) was

first delivered with the Cobalt-60 Gamma Knife system by Leksell in 1951.3 Today, SRS can also be delivered

via the linear accelerator (LINAC) system and proton beam system. It is

usually indicated in patients with oligo-brain metastases (≤4) with a

diameter of less than 4 cm.4 It is

particularly advantageous for lesions in the deep brain parenchyma that

are not easily accessible by surgery. A frame-based system was initially

used to immobilise the patient. A frameless system was later developed to

minimise patient suffering and was reported to have comparable outcomes to

the framed-based system.5 Since the

introduction of a frameless system, SRS or even fractionated stereotactic

radiotherapy has been increasingly used to treat patients with oligo-brain

metastases. Patients do not have to undergo painful frame placement.

Rather, they undergo simple planning procedures over 2 consecutive days.

The patient is required to return only for mould fitting and planning of

computed tomography. Together with diagnostic fine-cut magnetic resonance

imaging co-registration, oncologists can easily contour the target on the

radiotherapy planning system. With the use of the ExacTrac system

(Brainlab AG, Germany) to verify treatment position, the magnitude of

error is reported to be only 0.7 mm, and the mean deviation between

frame-based and image-guided initial positioning is just 1.0 mm (standard

deviation, 0.5 mm).6 A frameless

system became one of the choices of treatment in SRS and was included in

the ASTRO policy.7 The recommended

dosages according to the RTOG 9005 trial are 24 Gy, 18 Gy, and 15 Gy for

tumours of ≤20 mm, 21-30 mm, and 31-40 mm in maximum diameter,

respectively.8 For framed SRS,

1-year local progression-free survival (PFS) was reported to be up to 70%

to 90%, and median overall survival (OS) of 6 to 12 months.9 10 11 12 13 14 15 The outcomes of frameless SRS have been reported only

in limited series, with 1-year local control of 79% to 95%.5 16 17 18

Patient selection and tailor-made management are

indeed challenging. Several scoring systems have been modelled to predict

survival of patients with brain metastases, including the Radiation

Therapy Oncology Group Recursive Partitioning Analysis (RTOG RPA),19 Basic Score for Brain Metastases (BSBM),20 the Score Index for Radiosurgery in Brain Metastases

(SIR),21 Graded Prognostic

Assessment (GPA),22 and

Disease-Specific Graded Prognostic Assessment (DS-GPA).23 These scoring systems were developed at a time when

treatment strategies were also rapidly evolving with the availability of

more accurate diagnostic imaging, better radiotherapy techniques, and more

effective systemic and targeted agents. A paradigm shift to more

aggressive treatment of oligo-metastasis as a result of longer cancer

survivorship now requires further validation of these scoring systems.

In this study, we reviewed the outcomes of patients

who underwent LINAC-based frameless SRS and identified prognostic factors

that affect survival. By doing so, we hope to gain a better understanding

of which patients will benefit from SRS without jeopardising their quality

of life.

Methods

Records of patients who underwent frameless SRS for

limited brain metastases in a university-affiliated hospital between

January 2010 and July 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Patient data

were extracted from paper records and the Clinical Management System of

the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong by investigators in charge of the study.

Data extracted included gender, age, type of primary malignancy, date of

diagnosis of malignancy and brain metastases, extracranial disease status

and control at treatment time, diagnostic and monitoring modalities,

presence of convulsions, and steroid and anticonvulsant use before and

after treatment period. Treatment details including immobilisation

technique, number of lesions, dose and fractionation, and volume of

lesions were reviewed from department records and the Brainlab iplan

system (Brainlab AG, Germany). Prognostic scoring including RTOG RPA,

BSBM, SIR, and GPA were calculated (Appendix 1 19

20 21

22 23).

Outcome parameters including local and distant

brain control, PFS, and OS were generated using SPSS (Windows version

22.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). Univariable analysis with Cox

proportional hazards model was performed to generate prognostic factors

for local and distinct brain PFS (defined as the time from treatment to

documented local progression/distinct brain progression or death) and OS.

For each outcome, statistically significant non-modifiable patient and

disease factors in univariable analysis together with important treatment

factors were included in respective multivariable analysis using Cox

proportional hazards model. The enter method was used for variable

selection process. Kaplan-Meier survival curve for OS was generated for

different prognostic scoring groups and log rank significance was

calculated. The study was approved by clinical research ethics committee

of the NTEC-CUHK Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, with patient

informed consent waived.

Results

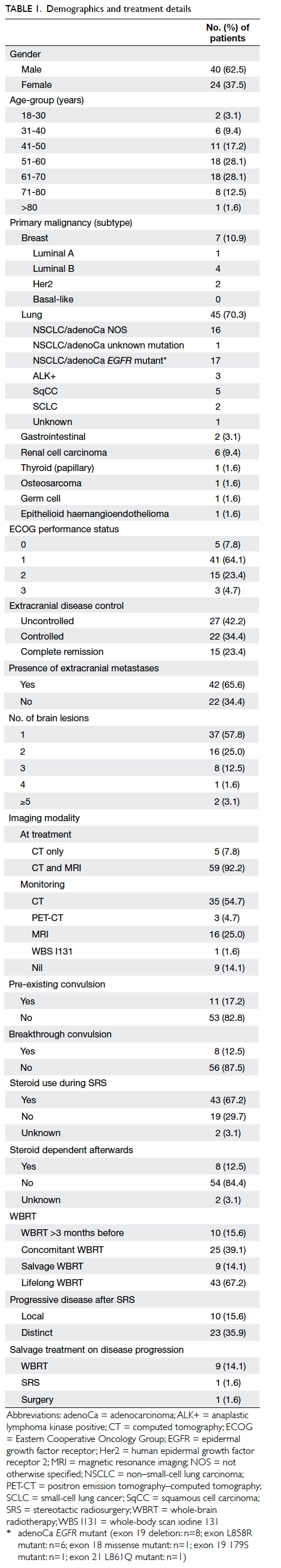

Demographics

A total of 68 patients were screened during the

study period. Four patients who were treated with fractionated

stereotactic radiotherapy and single-fraction SRS in the same treatment

were excluded, and thus 64 patients were included. All patients were

treated with frameless LINAC-based SRS with ExacTrac system verification,

while contouring and dosimetry with the Brainlab iplan system. Dose

administered was based on tumour diameter: 22 Gy to lesions of ≤2 cm, 18

Gy to lesions of 2.1-3.0 cm, and 15 Gy to lesions of 3.1-4.0 cm. A 1.5-mm

margin was allowed from gross tumour volume to planning target volume.

Deviation of dose prescription from departmental protocol was permitted at

the individual physician’s discretion.

Among the 64 patients, there were 40 men and 24

women. The median age at the time of treatment was 58 years (range, 22-95

years). The median Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

was 1 (range, 0-3), and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score was 80

(range, 40-100). Primary disease included carcinoma of breast (n=7), lung

(n=45), gastrointestinal (n=2), renal cell (n=6), thyroid (n=1),

osteosarcoma (n=1), germ cell (n=1), and epithelioid haemangioendothelioma

(n=1). Further details of demographics are summarised in Table

1.

Treatment

A total of 94 lesions were treated with a dose of

12 Gy to 22 Gy according to size (12 Gy, n=6; 15 Gy, n=12; 16 Gy, n=2; 18

Gy, n=48; 20 Gy, n=14; 22 Gy, n=12). The median dose was 18 Gy. The median

size of lesion treated was 19 mm (range, 3-43 mm).

Outcomes

The median follow-up time was 11.5 (range,

0.4-56.4) months. One-year actuarial local control rate was 72% (95%

confidence interval [CI], 57%-83%) and distant control rate was 71% (95%

CI, 56%-82%). The median local PFS was 11.2 (95% CI, 8.4-11.2) months. The

median distinct brain PFS was 10.8 (95% CI, 8.4-13.1) months. The median

OS was 13.0 (95% CI, 10.6-11.3) months.

Toxicities

Four (6.3%) patients had acute toxicities, mainly

brain oedema, and one patient had a seizure for 3 days after treatment.

Eight (12.5%) patients had delayed seizure after a median time of 10.5

months. One patient had radionecrosis confirmed pathologically after

surgical resection. There were 43 (67.2%) patients who were prescribed

steroid before treatment, and eight (12.5%) patients became steroid

dependent until their demise. Steroid prescription was not found to affect

OS significantly. Nonetheless among the steroid group, becoming steroid

dependent was associated with poorer prognosis, with a median OS in the

steroid-dependent group of 0.92 months versus 13.6 months in the

non–steroid-dependent group (P<0.005, log rank; Appendix 2, Fig a). The worse survival of steroid-dependent

patients was independent of volume of brain metastases.

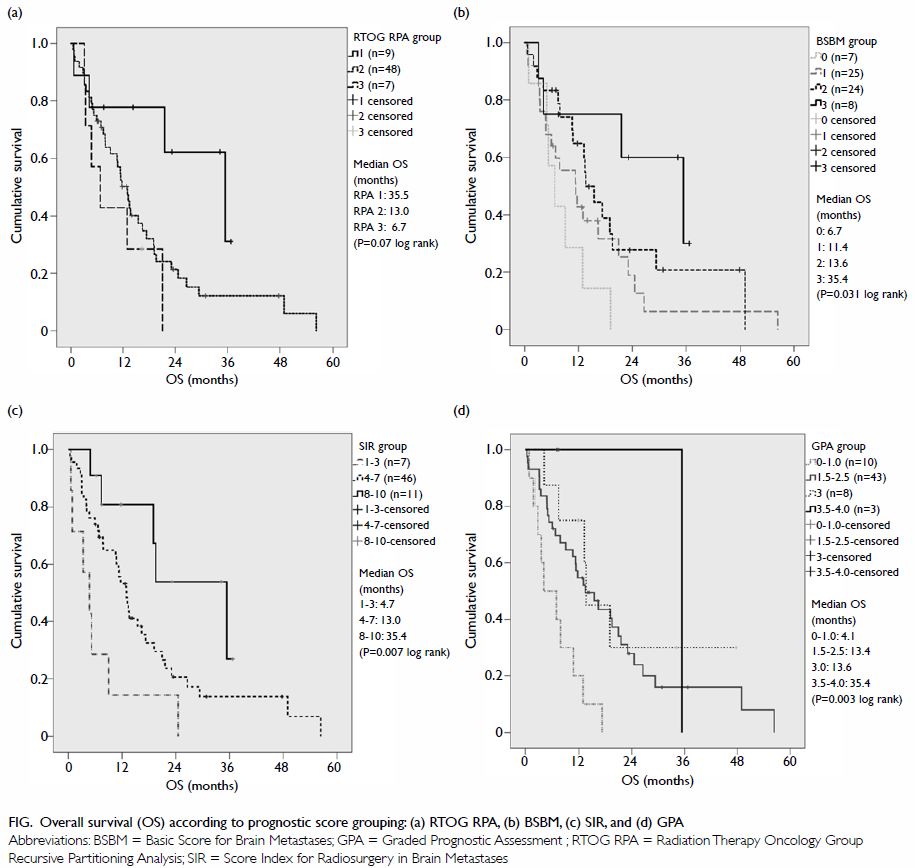

Figure. Overall survival (OS) according to prognostic score grouping: (a) RTOG RPA, (b) BSBM, (c) SIR, and (d) GPA

Prognostic patient and disease factors

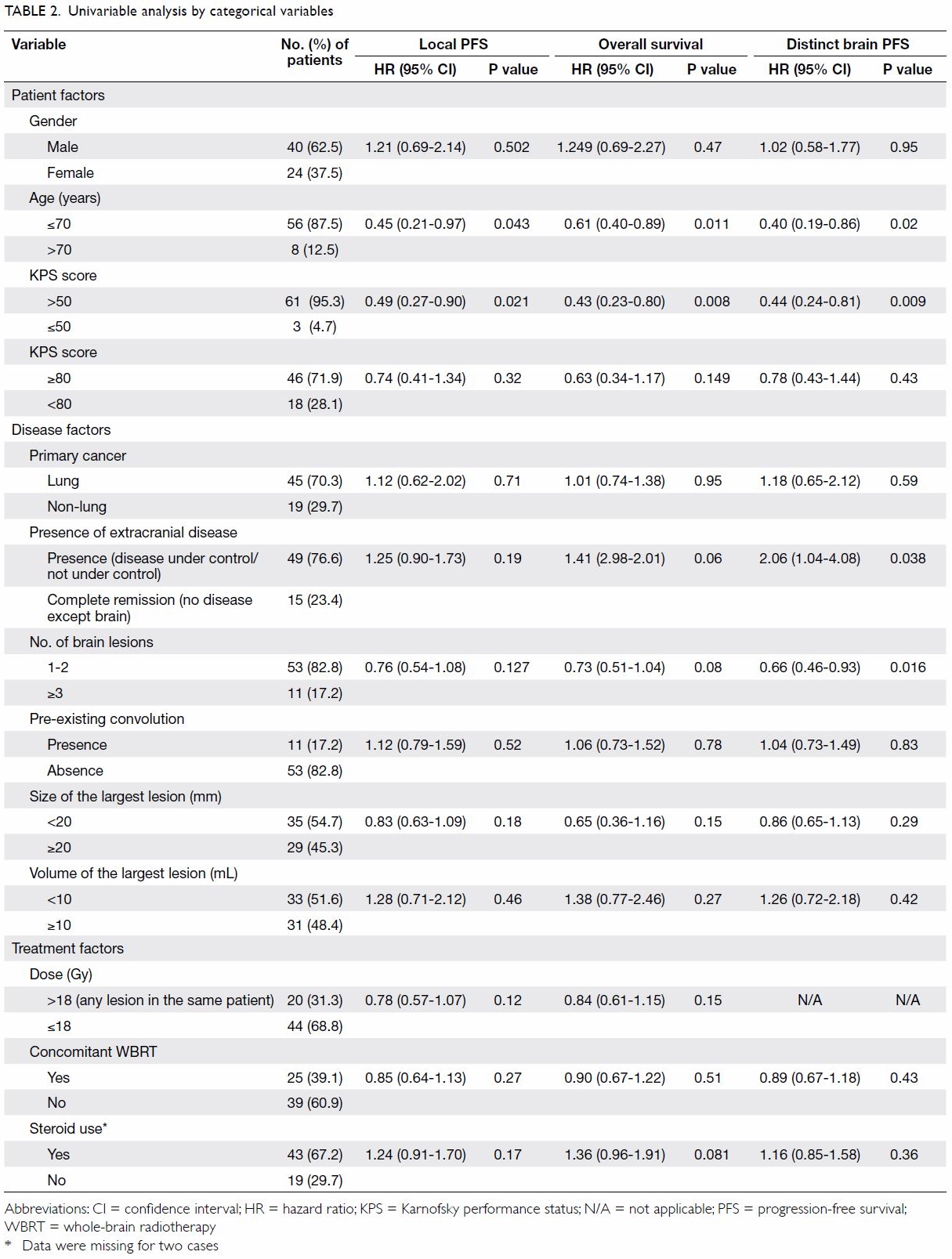

Potential prognostic factors of survival including

patient factors such as gender, age, and performance status; and disease

factors such as primary cancer, presence of extracranial disease,

pre-existing convulsion, number of brain lesions, and size and volume of

the largest lesion were examined with reference to decision for SRS

treatment by univariable analysis using Cox proportional hazards model. It

was found that OS was associated significantly with age (≤70 vs >70

years; P=0.011) and KPS score (>50 vs ≤50; P=0.008). Local PFS was

associated significantly with age (≤70 vs >70 years; P=0.043) and KPS

score (>50 vs ≤50; P=0.021). Distinct brain PFS was associated

significantly with age (≤70 vs >70 years; P=0.02), presence of

extracranial disease (presence vs absence; P=0.038), KPS score (>50 vs

≤50; P=0.009), and number of brain lesions (<1-2 vs ≥3; P=0.016).

Results of univariable analysis are summarised in Table 2.

Treatment factors

Dose relationship

Dose relationship for each lesion was analysed

separately. Lesions prescribed >18 Gy had statistically significant

superior time to progression (radiologically documented local progression)

than those given ≤18 Gy, with a 1-year local control rate of 88% vs 60% (Appendix 2, Fig b). Some patients had more than one lesion

treated with different doses. Nonetheless after taking into account the

highest dose given in the same patient, dose did not affect local PFS or

OS significantly (Table 2); dose was not analysed in distinct brain

PFS as it should not affect distant brain progression.

Effect of whole-brain radiotherapy

With particular reference to the effect of

whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), it was found that concomitant WBRT

(within 3 months of treatment with SRS) did not have a statistically

significant impact on OS, local PFS, or distant brain PFS (Table

2).

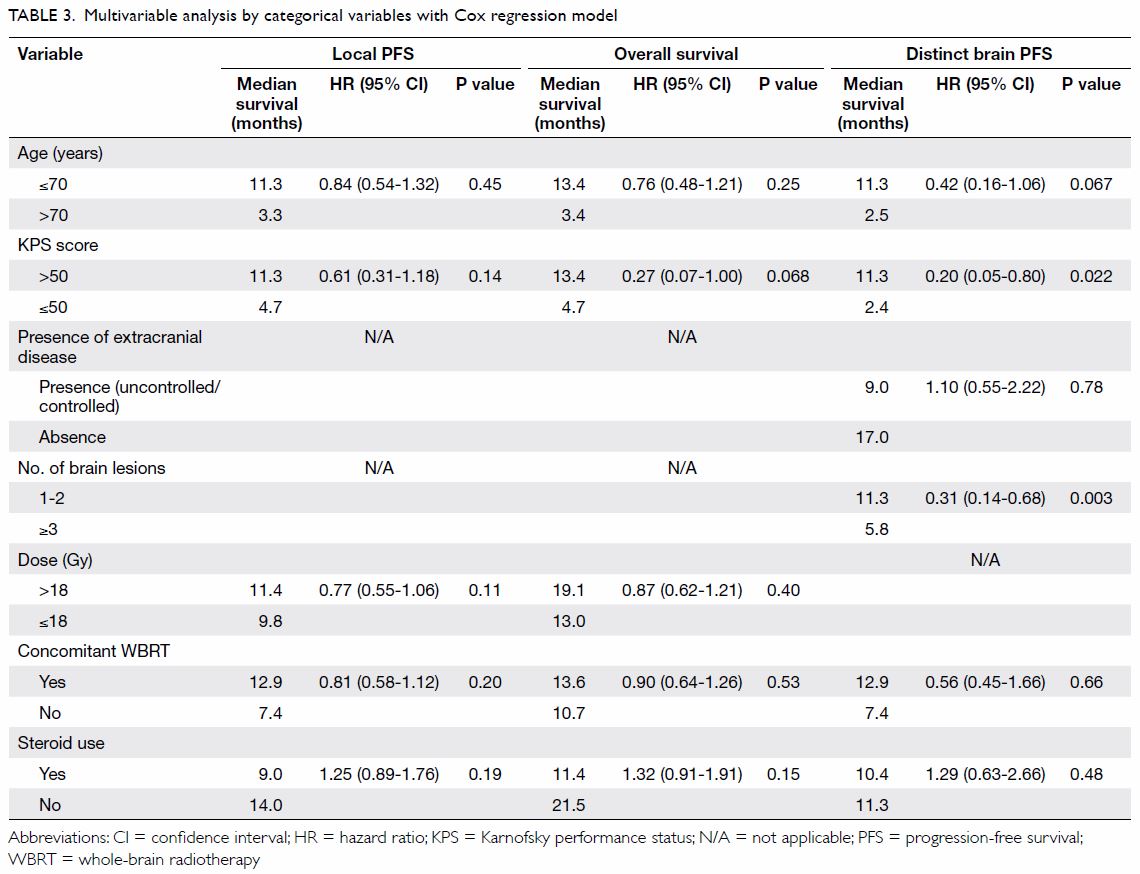

Multivariable analysis

Multivariable analysis using Cox proportional

hazards model and taking patient, disease, and treatment factors into

account identified that statistically significant factors associated with

distinct brain PFS were KPS score (>50 vs ≤50; P=0.022, hazard ratio

[HR]=0.20, 95% CI=0.05-0.80) and number of brain lesions (1-2 vs ≥3;

P=0.003, HR=0.31, 95% CI=0.14-0.68) [Table 3].

Primary lung cancer

Of note, a large number of patients in the group

had primary lung cancer (n=45), most of which were non–small-cell lung

cancer (NSCLC) [n=42]. Among NSCLC patients, a sensitive activating EGFR

mutation (exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R mutation) was present in 14.

Three other patients carried a less common mutation: exon 21 861Q (n=1),

exon 18 missense (n=1), and exon 18 179S (n=1). Patients with an exon 19

deletion or exon 21 L858R mutation had superior OS compared with the

non-mutational group (P=0.019, HR=0.281, 95% CI=0.097-0.814) but there was

no statistically significant difference in local or distant brain control.

Among the 14 patients with sensitive activating EGFR mutation,

three patients who were diagnosed with brain metastases received WBRT

before SRS treatment, and six patients were given SRS together with WBRT.

Again, concomitant WBRT was not shown to affect local/distinct brain PFS

or OS. For epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–tyrosine kinase

inhibitor (TKI) treatment, 12 of 14 patients had lifelong EGFR-TKI

treatment, with a median survival of 19.5 months; one with exon 19

deletion and one with exon 18 missense deletion did not have EGFR-TKI

treatment. There were seven patients who were prescribed EGFR-TKI before

SRS treatment (range of duration, 5.7-21.4 months), and eight patients who

were started on or continued on more lines of EGFR-TKI after SRS

treatment.

Association with available prognostic scoring

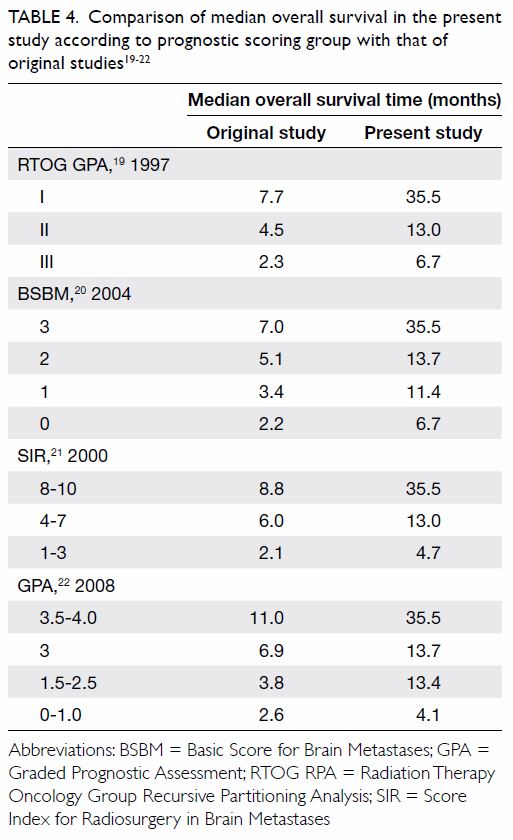

Overall survival was significantly associated with

BSBM (P=0.031, log-rank), SIR (P=0.007, log-rank), and GPA (P=0.003,

log-rank) [Fig]. A comparison of median survival of the current

study with the other original studies is shown in Table 4.19 20 21

22 Of note, DS-GPA was not

analysed due to the small number of patients with breast,

gastrointestinal, and renal cell primaries. The calculation of GPA and

DS-GPA of lung primary was the same.

Table 4. Comparison of median overall survival in the present study according to prognostic scoring group with that of original studies19 20 21 22

Discussion

Brain metastasis has previously been considered an

end-of-life event. With the development of new systemic therapies that are

effective in both extracranial and intracranial diseases, together with a

better understanding from clinical trials of the advantages of SRS,

oncologists are more willing to offer SRS to patients with limited brain

metastases.

At the other extreme, studies have compared the

efficacy of WBRT with supportive care in patients with advanced brain

metastases. The latest news from the QUARTZ trial, conducted by the UK

Medical Research Council Group, presented at the American Society of

Clinical Oncology Meeting in 201524

(full paper awaited) was striking for oncologists. They randomly allocated

538 NSCLC patients with brain metastases that were not amenable to surgery

or SRS to either optimal supportive care (OSC) plus WBRT (20 Gy/5

fractions) or OSC alone. There was no significant difference in survival

between the OSC+WBRT group and OSC-alone group, with the median survival

being 65 and 57 days, respectively. Quality of life was also assessed in

this study. The difference between the mean quality-adjusted life-years

was -1.9 days only (OSC+WBRT 43.3 vs OSC-alone 41.4 days) and did not meet

the initial defined criteria of significance. These data revealed that we

are encountering a group of patients with very heterogeneous tumour

behaviour and thus personalised treatment is required.

This retrospective study included patients who

underwent frameless SRS during January 2010 to July 2015, after

commencement of frameless SRS treatment in our centre. Limitations of this

study including small number of patients and information bias are

inevitable. Nonetheless, the outcomes of patients with brain metastases

who underwent frameless SRS in our centre are compatible with those from

other large clinical trials that used frame-based systems in terms of

control rate, median OS and PFS, and toxicities. Approximately 13% of

patients had a complication of steroid dependence that may have been due

to treatment or natural disease progression. Steroid dependence was

associated with poor survival, independent of volume of tumour. Prolonged

use of steroid has been associated with decreased immunity that may

underlie superimposed infection. Therefore, tailing down of steroid dose

as early as possible in accordance with patient symptoms is strongly

recommended.

This study revealed that OS was significantly

associated with previously identified prognostic scoring group such as

BSBM, SIR, and GPA. Among the three, BSBM and GPA are more convenient to

use as only three or four factors are considered respectively, and the

information should be easily available in a clinic (including age, KPS,

control of primary cancer, presence of extracranial metastases, and number

of brain metastases). Data relating to volume of the largest brain lesion

included in SIR may not always be available as the reporting radiologist

may only report lesion diameter. In terms of patient selection, for

patients with GPA of 0-1.0, the median OS was 4.1 months in our study

compared with 2.6 months in the original study, and similar to that of

patients given WBRT alone. It may be more appropriate to prescribe WBRT

alone or best supportive care for this group of patients in lieu of SRS.

An important observation from the result of our study is that survival of

patients was significantly improved compared with a previous cohort (Table

4). This reflects a significant improvement in systemic treatment

over the last decade. Thus, the use of high technology radiation

techniques such as SRS is increasingly considered by radiation oncologists

to achieve the best outcomes.

Another important aim of this study was to identify

prognostic factors of survival in order to avoid futile treatment in those

patients who will have a poor outcome despite SRS. Due to the small number

of patients in this study, we were not able to identify patients with

superior survival among different primaries, similar to DS-GPA. It is of

note that a large number of patients in our study had primary lung cancer.

In the NSCLC subgroup, patients with an activating EGFR mutation

had significantly better survival than those without mutation, and the

majority of this group had EGFR-TKI lifelong. Of note, EGFR-TKI has been

shown in various studies to have PFS and survival benefit in patients with

EGFR-activating mutation.25

26 27

28 29

30 31

32 In a recent retrospective

multi-institutional study with more than 300 patients, outcomes of

patients with EGFR-activating mutation were analysed following

treatment with upfront SRS followed by EGFR-TKI, upfront WBRT followed by

EGFR-TKI, and upfront EGFR-TKI.33

Patients in the upfront SRS and upfront WBRT group had significantly

superior OS and intracranial PFS compared with those with upfront

EGFR-TKI.33 Therefore, in patients

with oligo-brain metastases harbouring an EGFR-activating

mutation, SRS followed by EGFR-TKI should be considered a standard

treatment, and WBRT reserved until there is frank brain disease

progression to conserve cognitive function. In addition, SRS combined with

efficacious systemic treatment with good brain penetration while omitting

WBRT should also be considered in other primaries, although further

studies are awaited to validate the benefit.

The beneficial effect of WBRT in addition to SRS is

controversial. Recent evidence shows it improves local control but not

survival.34 35 Nonetheless, in view of toxicity of somnolence,

malaise and cognitive impairment with WBRT, many clinicians may prefer

delaying WBRT until there is frank disease progression after SRS. In a

recent meta-analysis, the benefit of additional WBRT was not observed in

patients who were 50 years old or younger in terms of survival or distant

brain control.36 Initial omission

of WBRT in this young age-group had no adverse effect on distant brain

relapse rate. We were unable to replicate improvement in brain control

with WBRT or demonstrate an interaction of age with benefit of concomitant

WBRT, possibly due to the small size and retrospective nature of our

current study. Number of brain metastases was identified as a significant

prognostic factor of brain PFS. Patients with three or more brain

metastases had worse PFS than those with one or two brain metastases (5.8

months vs 11.3 months). Again due to the small number of patients, we were

unable to demonstrate whether concomitant WBRT could improve brain PFS in

patients with three or more brain metastases. Further prospective studies

are warranted to verify whether concomitant WBRT should be considered in

patients with a higher disease load or age over 50 years.

Frameless SRS for oligo-brain metastases is

painless and well tolerated, and should be increasingly considered in

patients with good prognostic scores. Its combination with effective

systemic treatment has significantly improved survival over the past

decade. Nonetheless it is important to individualise treatment for

patients with brain metastases according to their inherited prognostic

risk factors. High precision treatment with SRS with or without WBRT

should be offered to patients with oligo-brain metastases with good

prognostic scores and favourable primary histology. For patients with EGFR-activating

mutation, SRS followed by EGFR-TKI is a superior choice of treatment.

Based on the latest evidence, it may be advisable to give SRS alone and

reserve WBRT as salvage for patients with limited brain metastases who are

50 years or younger. Further, WBRT alone can be offered to patients with

multiple symptomatic brain metastases and unfavourable prognostic scores.

Best supportive care with dexamethasone alone may be considered for

patients with very poor performance status.

Conclusions

Frameless SRS is effective and safe for patients

with oligo-metastases of brain. Identification of patients with brain

metastases who would benefit from SRS is important. Current available

prognostic scoring systems provide a good estimation of survival.

Frameless SRS should be increasingly considered in patients with

favourable prognostic scores.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr SF Leung and Dr Kennis

Ngar of Department of Clinical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong

Kong for their professional opinion and support in this study.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

References

1. Tsao MN, Lloyd NS, Wong RK, et al.

Radiotherapeutic management of brain metastases: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 2005;31:256-73. Crossref

2. Nieder C, Spanne O, Mehta MP, Grosu AL,

Geinitz H. Presentation, patterns of care, and survival in patients with

brain metastases: what has changed in the last 20 years? Cancer

2011;117:2505-12. Crossref

3. Leksell L. The stereotaxic method and

radiosurgery of the brain. Acta Chir Scand 1951;102:316-9.

4. Lo SS. Stereotactic radiosurgery.

Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1423298-overview#a2.

Accessed 19 Mar 2015.

5. Minniti G, Scaringi C, Clarke E,

Valeriani M, Osti M, Enrici RM. Frameless linac-based stereotactic

radiosurgery (SRS) for brain metastases: analysis of patient repositioning

using a mask fixation system and clinical outcomes. Radiat Oncol

2011;6:158. Crossref

6. Ramakrishna N, Rosca F, Friesen S,

Tezcanli E, Zygmanszki P, Hacker F. A clinical comparison of patient setup

and intra-fraction motion using frame-based radiosurgery versus a

frameless image-guided radiosurgery system for intracranial lesions.

Radiother Oncol 2010;95:109-15. Crossref

7. ASTRO Policies for Stereotactic

radiosurgery (SRS). Available from: https://www.astro.org/uploadedFiles/

Main_Site/Practice_Management/Reimbursement/ASTROSRSModelPolicy.pdf.

Accessed 2014.

8. Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L, et al.

Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated

primary brain tumors and brain metastases: final report of RTOG protocol

90-05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;47:291-8. Crossref

9. Sneed PK, Lamborn KR, Forstner JM, et

al. Radiosurgery for brain metastases: is whole brain radiotherapy

necessary? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;43:549-58. Crossref

10. Pirzkall A, Debus J, Lohr F, et al.

Radiosurgery alone or in combination with whole-brain radiotherapy for

brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:3563-9. Crossref

11. Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW, et

al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic

radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: Phase

III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet 2004;363:1665-72. Crossref

12. Cho KH, Hall WA, Gerbi BJ, Higgins PD,

Bohen M, Clark HB. Patient selection criteria for the treatment of brain

metastases with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol 1998;40:73-86. Crossref

13. Varlotto JM, Flickinger JC, Niranjan

A, Bhatnagar AK, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD. Analysis of tumor control and

toxicity in patients who have survived at least one year after

radiosurgery for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys

2003;57:452-64. Crossref

14. Bhatnagar AK, Flickinger JC,

Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for four or more

intracranial metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;64:898-903. Crossref

15. Nieder C, Grosu AL, Gaspar LE.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for brain metastases: a systematic review.

Radiat Oncol 2014;9:155. Crossref

16. Pham NL, Reddy PV, Murphy JD, et al.

Frameless, real-time, surface imaging-guided radiosurgery: update on

clinical outcomes for brain metastases. Transl Cancer Res 2014;3:351-7.

17. Breneman JC, Steinmetz R, Smith A,

Lamba M, Warnick RE. Frameless image-guided intracranial stereotactic

radiosurgery: clinical outcomes for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys 2009;74:702-6. Crossref

18. Muacevic A, Kufeld M, Wowra B, Kreth

FW, Tonn JC. Feasibility, safety, and outcome of frameless image-guided

robotic radiosurgery for brain metastases. J Neurooncol 2010;97:267-74. Crossref

19. Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, et al.

Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three

Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997;37:745-51. Crossref

20. Lorenzoni J, Devriendt D, Massager N,

et al. Radiosurgery for treatment of brain metastases: estimation of

patient eligibility using three stratification systems. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys 2004;60:218-24. Crossref

21. Weltman E, Salvajoli JV, Brandt RA, et

al. Radiosurgery for brain metastases: a score index for predicting

prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46:1155-61. Crossref

22. Sperduto PW, Berkey B, Gaspar LE,

Mehta M, Curran W. A new prognostic index and comparison to three other

indices for patients with brain metastases: an analysis of 1,960 patients

in the RTOG database. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;70:510-4. Crossref

23. Sperduto PW, Kased N, Roberge D, et

al. Summary report on the graded prognostic assessment: an accurate and

facile diagnosis-specific tool to estimate survival for patients with

brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:419-25. Crossref

24. Mulvenna PM, Nankivell MG, Barton R,

et al. Whole brain radiotherapy for brain metastases from non-small lung

cancer: Quality of life (QoL) and overall survival (OS) results from the

UK Medical Research Council QUARTZ randomised clinical trial (ISRCTN

3826061). J Clin Oncol 2015;33(Suppl);abstract8005.

25. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al.

Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J

Med 2009;361:947-57. Crossref

26. Han JY, Park K, Kim SW, et al.

First-SIGNAL: first-line single-agent iressa versus gemcitabine and

cisplatin trial in never-smokers with adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin

Oncol 2012;30:1122-8. Crossref

27. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et

al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth

factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol 2010;11:121-8. Crossref

28. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et

al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated

EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2380-8. Crossref

29. Jänne PA, Wang X, Socinski MA, et al.

Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib alone or with carboplatin and

paclitaxel in patients who were never or light former smokers with

advanced lung adenocarcinoma: CALGB 30406 trial. J Clin Oncol

2012;30:2063-9. Crossref

30. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et

al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for

European patients with advanced EGFR mutation–positive

non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:239-46. Crossref

31. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al.

Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with

advanced EGFR mutation–positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL,

CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet

Oncol 2011;12:735-42. Crossref

32. Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M, et al.

Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR

mutation–positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6):

analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials.

Lancet Oncol 2015;16:141-51. Crossref

33. Magnuson WJ, Lester-Coll NH, Wu AJ, et

al. Management of brain metastases in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naïve

epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer: a

retrospective multi-institutional analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1070-7. Crossref

34. Mehta MP, Tsao MN, Whelan TJ, et al.

The American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO)

evidence-based review of the role of radiosurgery for brain metastases.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;63:37-46. Crossref

35. Patil CG, Pricola K, Sarmiento JM,

Garg SK, Bryant A, Black KL. Whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) alone

versus WBRT and radiosurgery for the treatment of brain metastases.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD006121. Crossref

36. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al.

Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole-brain

radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: individual patient data

meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;91:710-7. Crossref