Treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp and face in Chinese patients: local experience at a regional hospital in Hong Kong

Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Feb;24(1):25–31 | Epub 12 Jan 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj176813

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Treatment of cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp and

face in Chinese patients: local experience at a regional hospital in Hong

Kong

TL Chow, FRCS (Edin), FHKAM (Surgery)1;

Wilson WY Kwan, FRCS (Edin), FHKAM (Surgery)1; CK Kwan, FRCR,

FHKAM (Radiology)2

1 Head and Neck Division, Department of

Surgery, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Oncology, United

Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr TL Chow (chowtl@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Angiosarcoma is a

rare aggressive sarcoma that occurs mostly in the skin of the head and

neck in the elderly population. The optimal management is dubious and

most studies are from Caucasian populations. We aimed to examine the

treatment and outcome of this disease in Chinese patients.

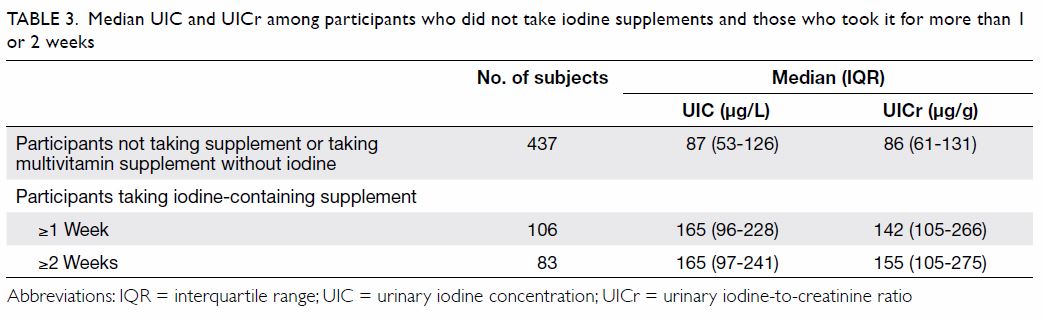

Methods: Data of patients with

histopathologically verified cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck

during December 1997 to September 2016 were retrieved from our hospital

cancer registry. The demographic data, clinicopathological information,

modality of treatment, and outcomes were reviewed.

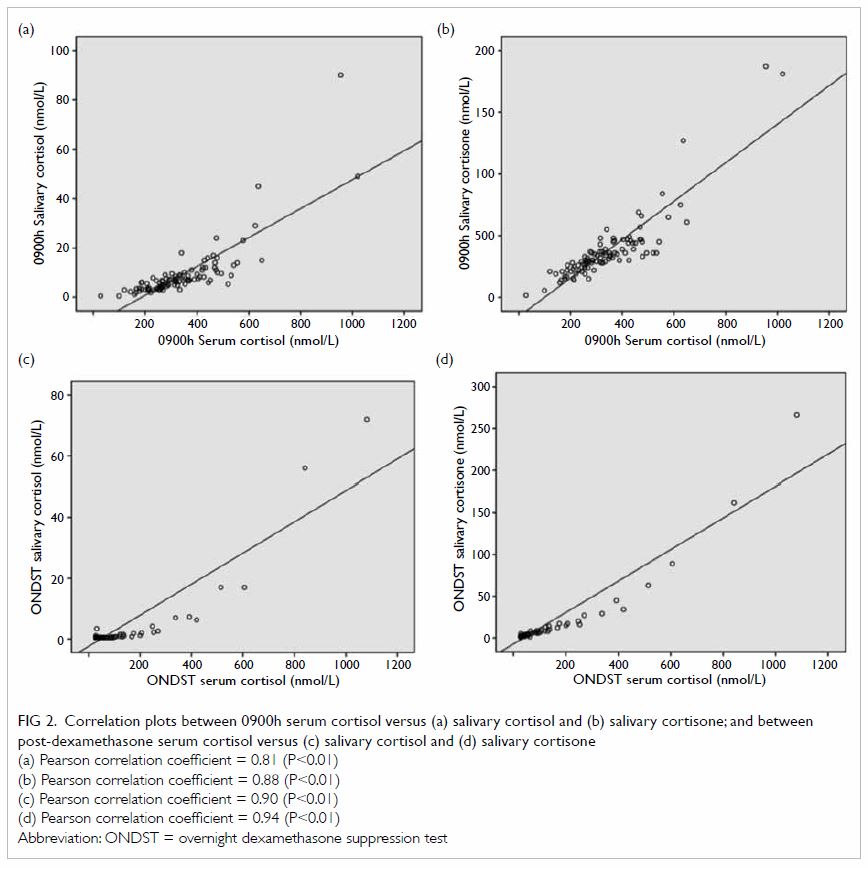

Results: During the study

period, 17 Chinese patients were treated. Their median age was 81 years.

The tumours were present in the scalp only (n=11), face only (n=4), or

both scalp and face (n=2). Only two patients had distant metastases. The

modalities of treatment were surgery (n=6), surgery and adjuvant

radiotherapy (n=1), palliative radiotherapy (n=5), or palliative

chemotherapy (n=3). The remaining two patients refused any treatment

initially. Of the seven patients treated surgically, there were four

local and two regional recurrences. The median time to relapse was 7.5

months. Overall, 16 patients had died; causes of death were

disease-related in 12 whereas four other patients died of inter-current

illnesses. One patient was still living with the disease. The median

overall survival was 11.1 months and the longest overall survival was 42

months.

Conclusion: The outcome of

angiosarcoma in our series is poor. A high index of suspicion is

mandatory for prompt diagnosis. Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended

following surgery. The benefit and role of systemic treatment in various

combinations with surgery or radiotherapy require further study.

New knowledge added by this study

- Reports of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face in the Chinese population are limited. Patient survival in this local study was worse than that of other studies.

- Literature review in this study supports the use of adjuvant radiotherapy to improve angiosarcoma control.

- An aggressive but not too radical surgery for head and neck cutaneous lesions is advocated.

- Combination therapy (surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic treatment) in various combinations should be considered.

Introduction

Angiosarcoma is a rare form of sarcoma of vascular

origin. It is notorious for its aggressive and relentless progression with

frequent local recurrence and distant metastasis.1

Owing to its scarcity and innocuous appearance at an early stage mimicking

an ordinary bruise or benign haemangioma, correct diagnosis is often

delayed for several months. This problem is compounded further because

most patients with angiosarcoma are elderly with frailty and co-morbidity,

and prognosis after surgery as the definitive therapy is gloomy. The

5-year overall survival (OS) has been variously reported as 24% to 35%.1 2

When radiotherapy (RT) is given as the main treatment, median survival is

only 8 months.3

Almost half (43%) of angiosarcomas originate from

the skin of the head and neck.1 2 Compared with truncal and

extremity angiosarcoma, the prognosis of cutaneous angiosarcoma (CAS) of

the head and neck is even worse. Perez et al2

indicated a greater need for flap or graft reconstruction after tumour

extirpation for head and neck CAS (HNCAS), a positive resection margin in

50%, and 5-year OS of 21.5%. Surgery was conventionally regarded as the

mainstay of therapy for HNCAS. Because of the poor results and frequent

margin involvement (78%),4 a

multidisciplinary approach with adjuvant RT has been advocated.

To the best of our knowledge, most articles about

HNCAS derived from a Caucasian population. We are not aware of any

reported series from ethnic Chinese populations. We therefore conducted

this retrospective study of HNCAS in the Chinese patients managed in our

hospital over the past two decades. Demographic data, clinicopathological

information, modality of treatment, and outcomes were reviewed. The latest

approaches to the treatment of this devastating disease are also

discussed.

Methods

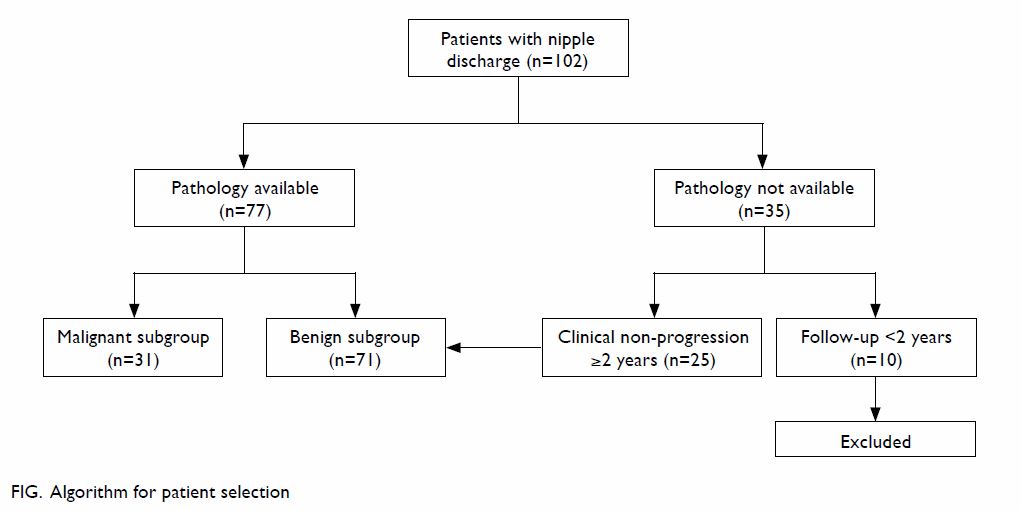

Records of patients with histopathologically

verified HNCAS from December 1997 to September 2016 were captured from the

head and neck cancer registry of our department. Only Chinese patients

were recruited. Patient data were prospectively collected and regularly

updated in the registry.

Tumours were classified as a unifocal/localised

versus multifocal/diffuse form. Unifocal/localised tumour was

characterised by a discrete lesion without macroscopic satellitosis; it

was considered operable and potentially curable. If gross satellite

lesions were present or the main tumour was too extensive to be removed

surgically, it was regarded as a multifocal/diffuse tumour that was

probably incurable. Superficial tumours were those confined to the skin

and subcutaneous tissue. Conversely, deep tumours were defined as

transgression beyond the subcutaneous layer, for example encroaching on

the underlying muscle or bone.

If the tumour was resectable, a wide excision with

at least a 3-cm margin was performed. The defects were reconstructed by

local scalp flap/ skin graft (scalp primary) or submental flap (face

primary).5 Neck dissection was

performed only in the presence of clinical or radiological evidence of

nodal spread. Adjuvant RT was not routinely administered. When disease was

deemed inoperable or the patient was unfit for surgery, palliative RT or

chemotherapy would be considered.

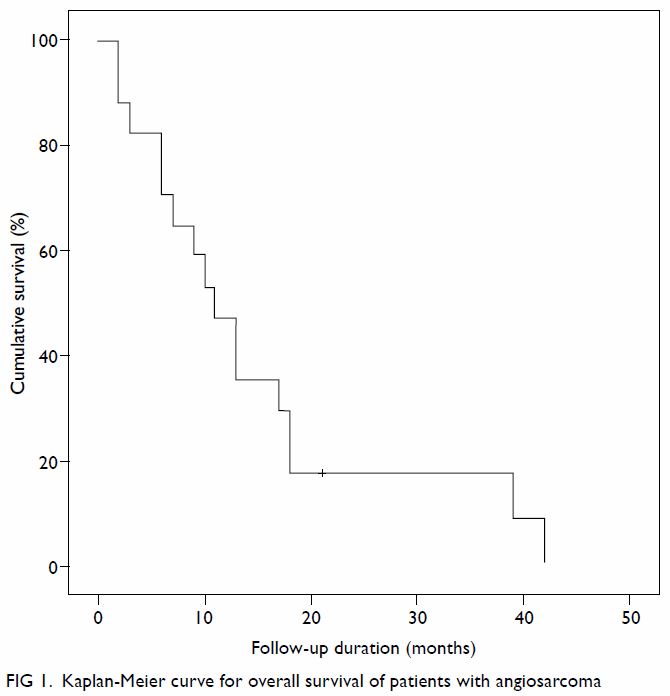

The OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to

patient death or last follow-up, and is expressed in Kaplan-Meier curve.

The data were computed using the SPSS (Windows version 20.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], United States). The principles outlined in the 2013 version

of the Declaration of Helsinki have been followed.

Results

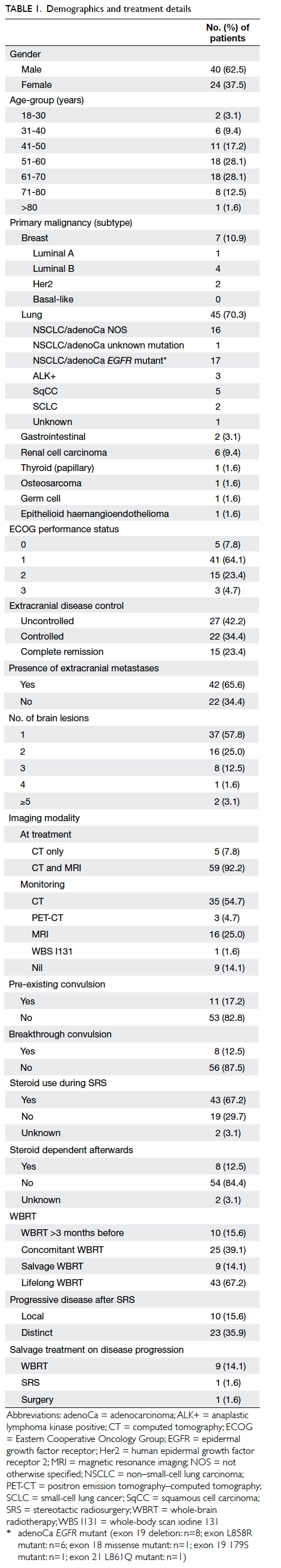

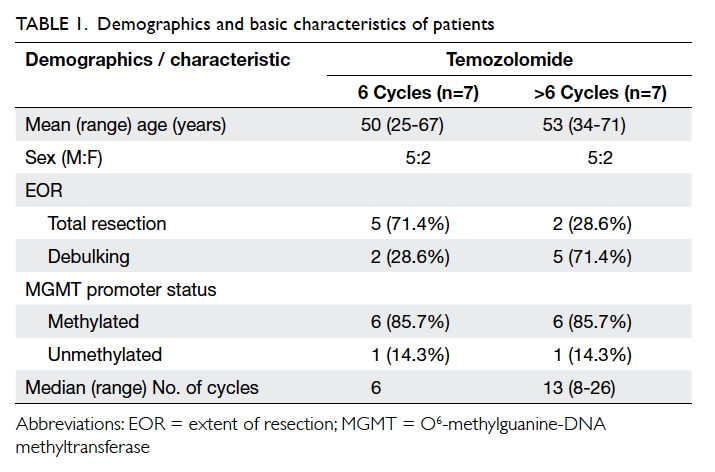

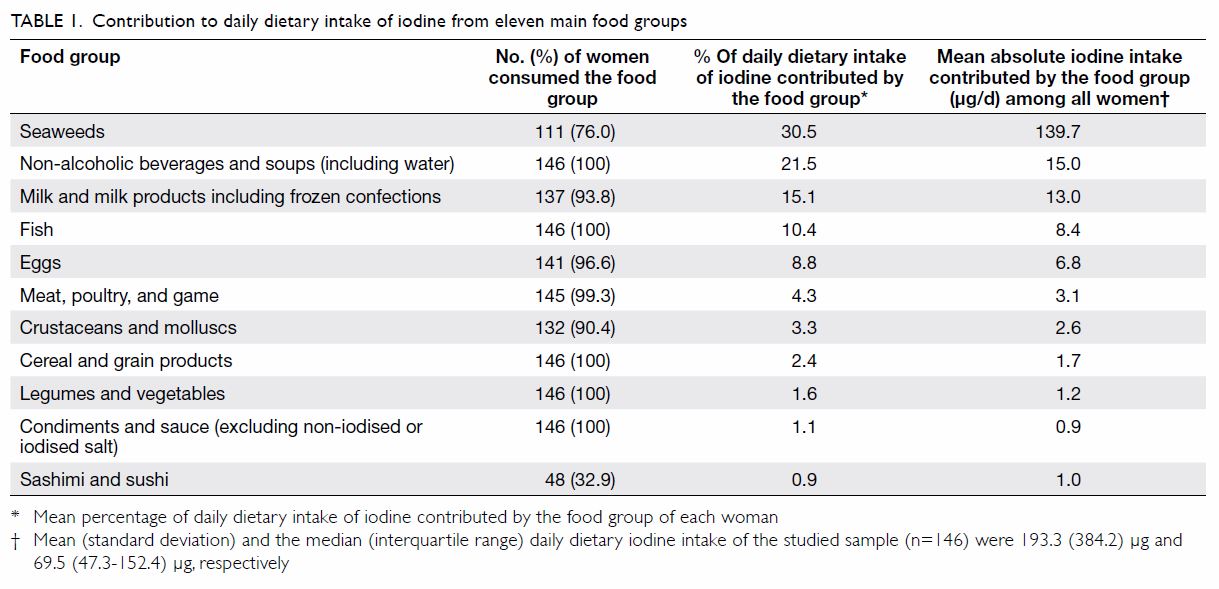

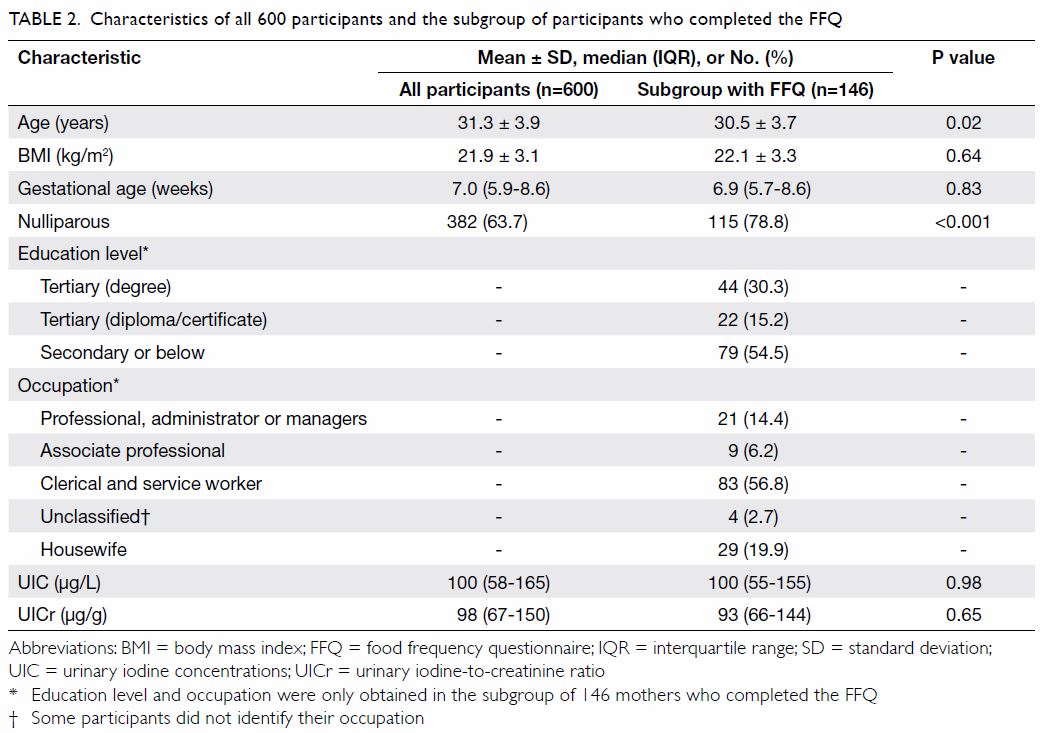

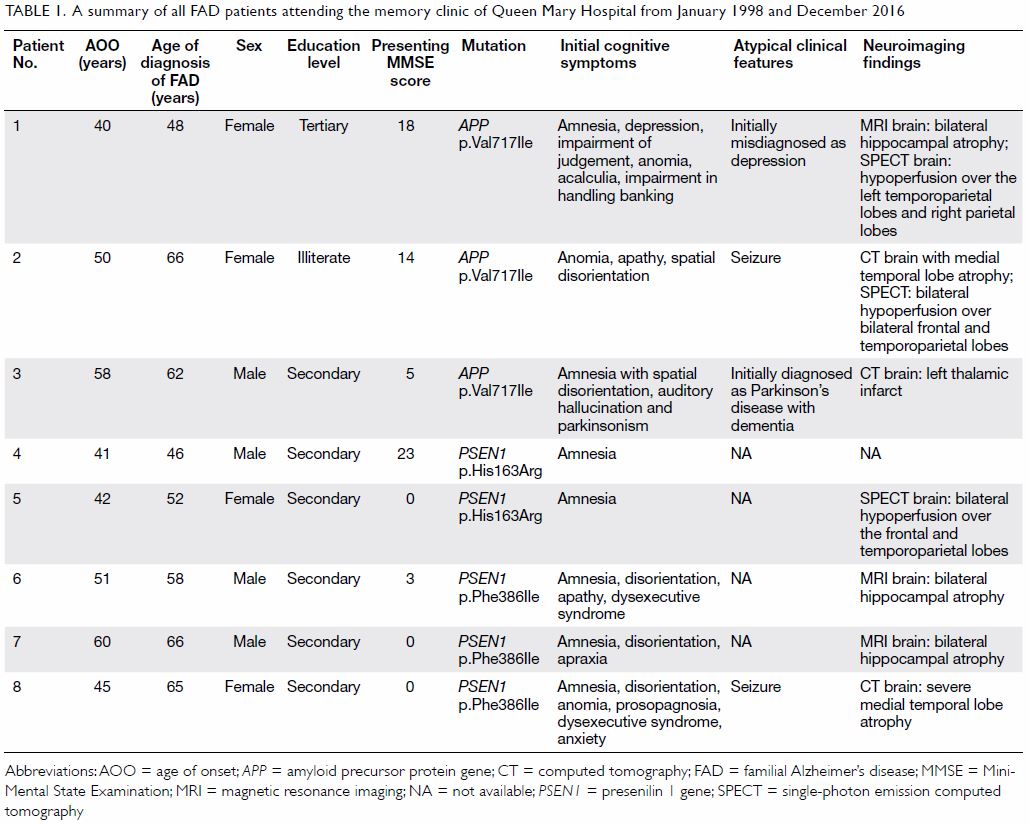

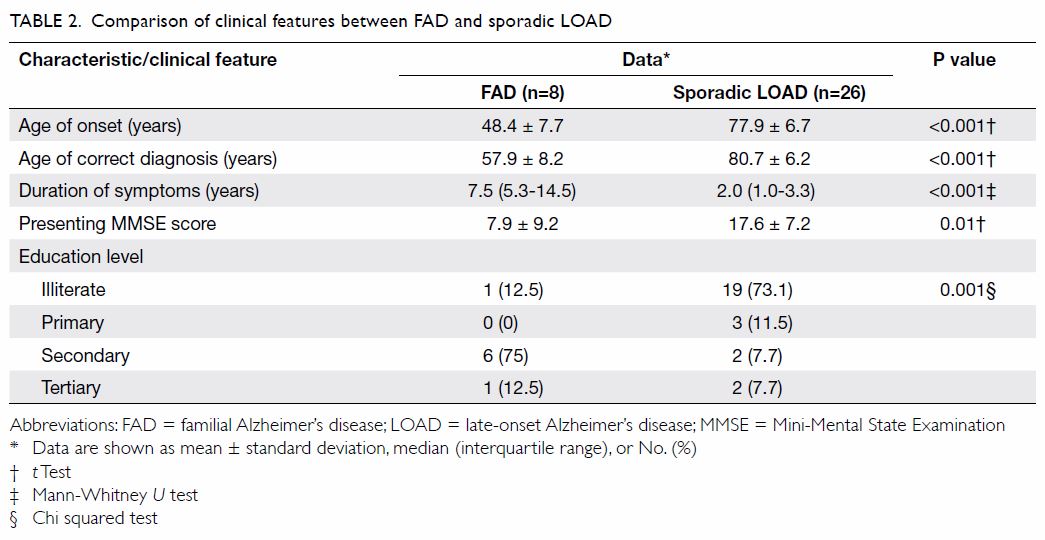

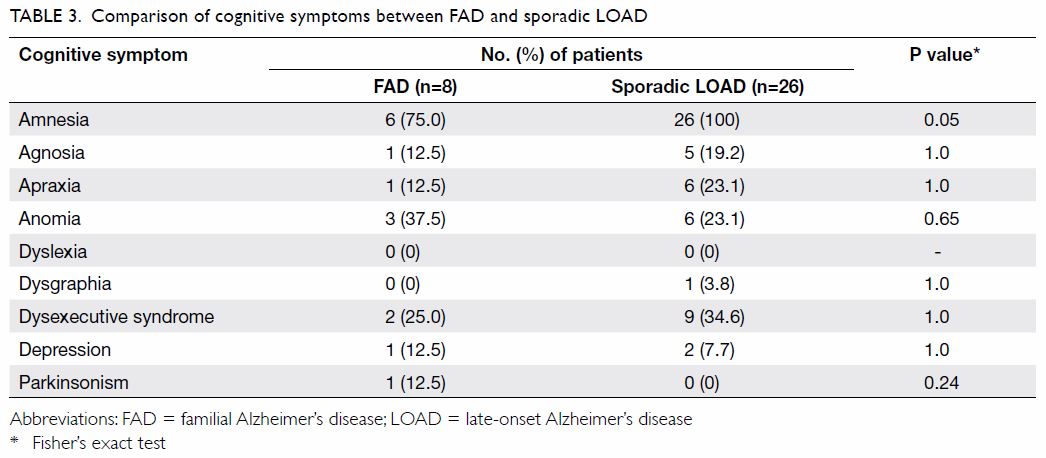

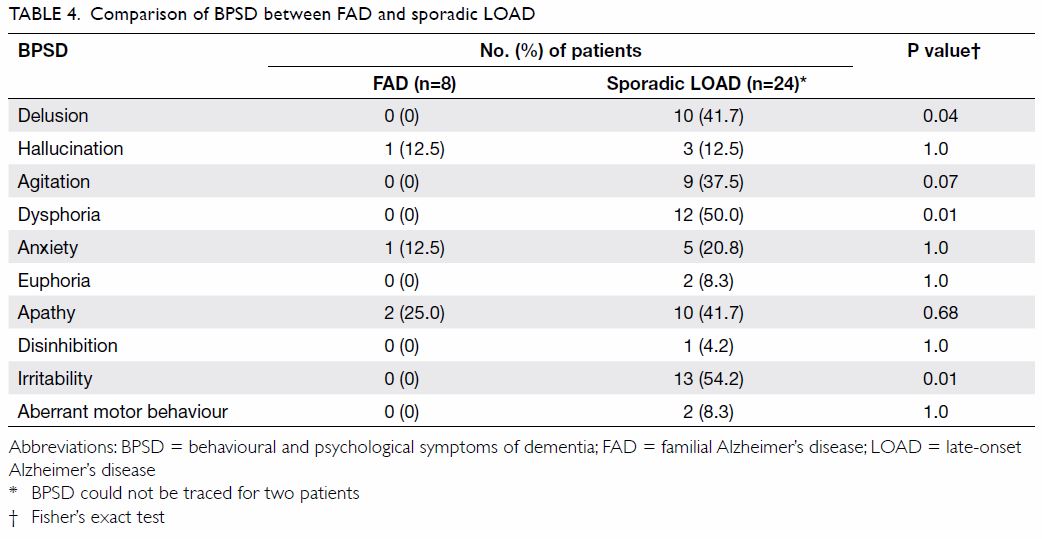

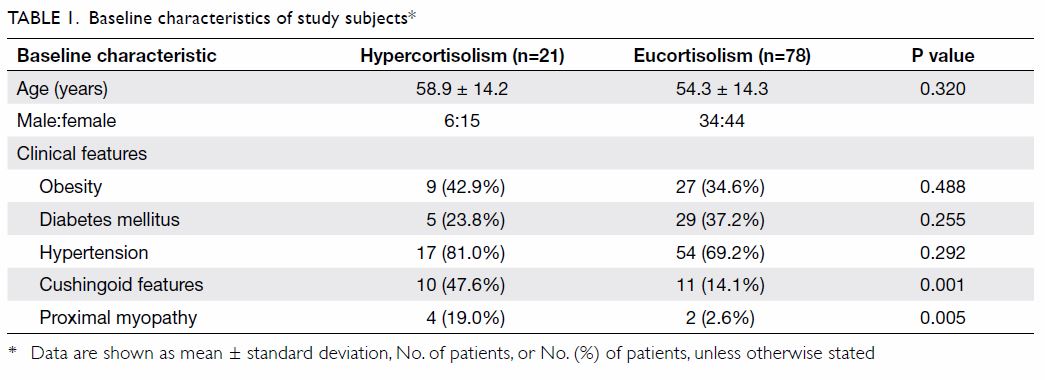

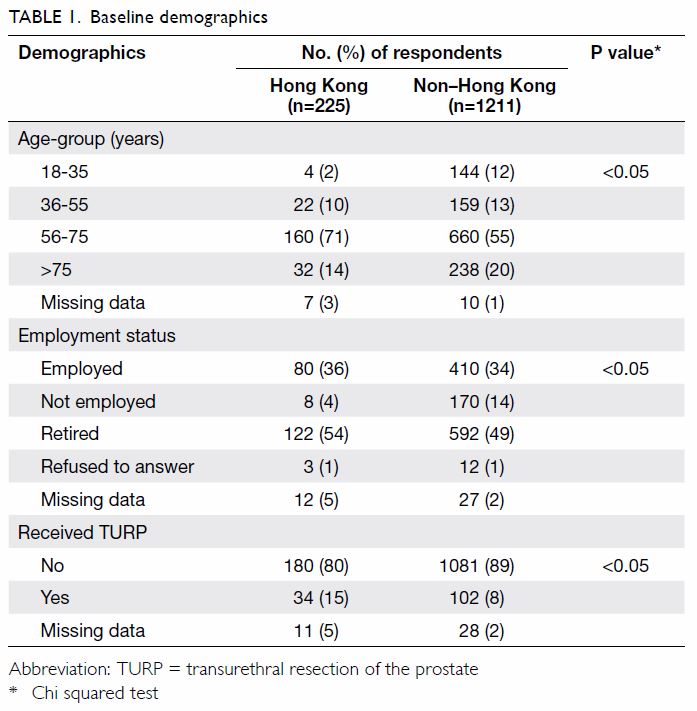

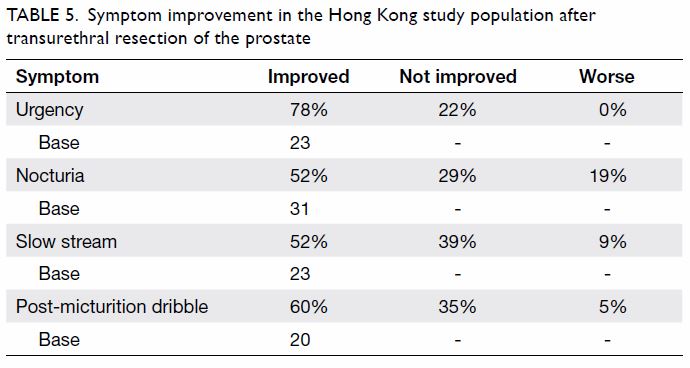

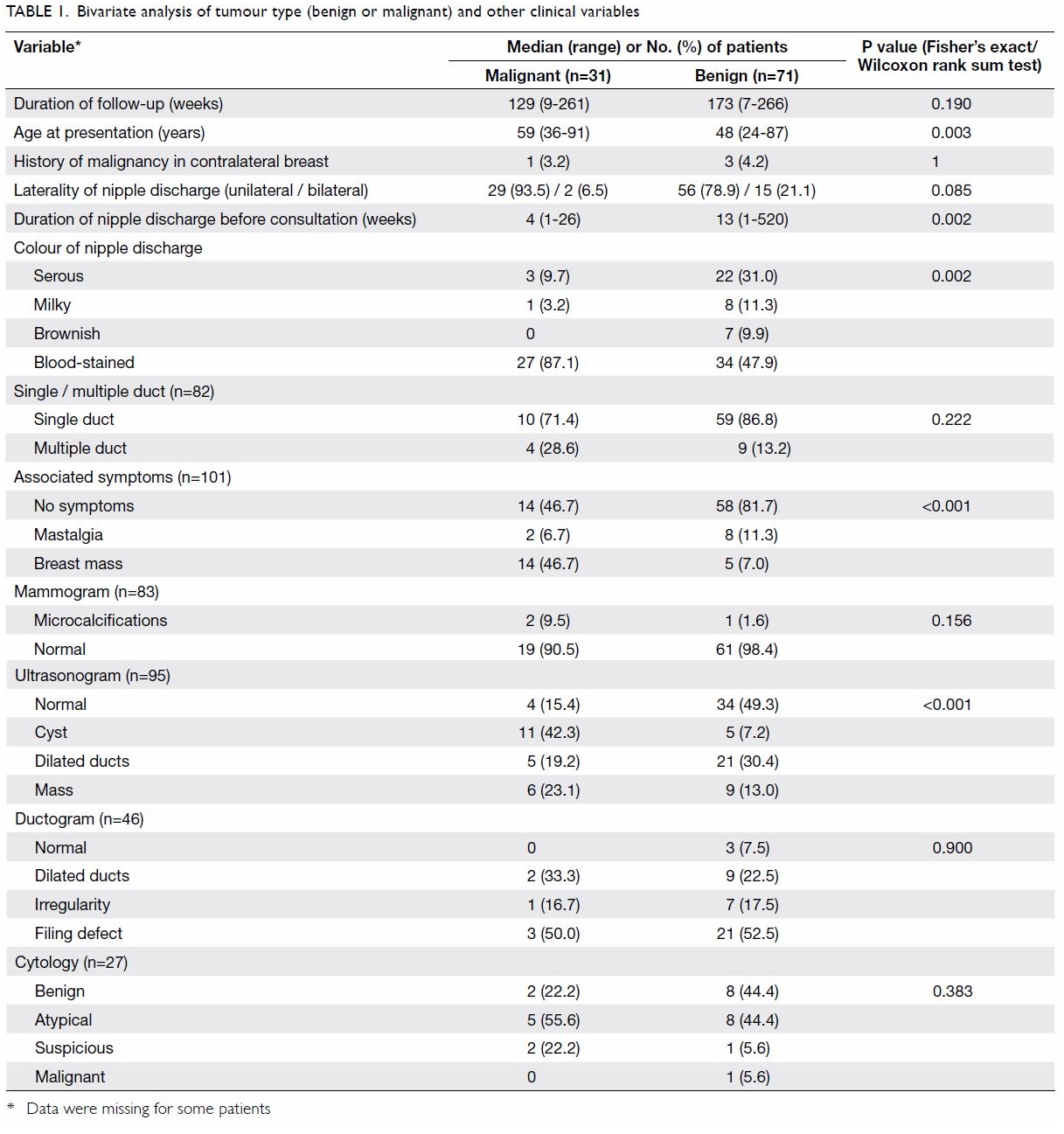

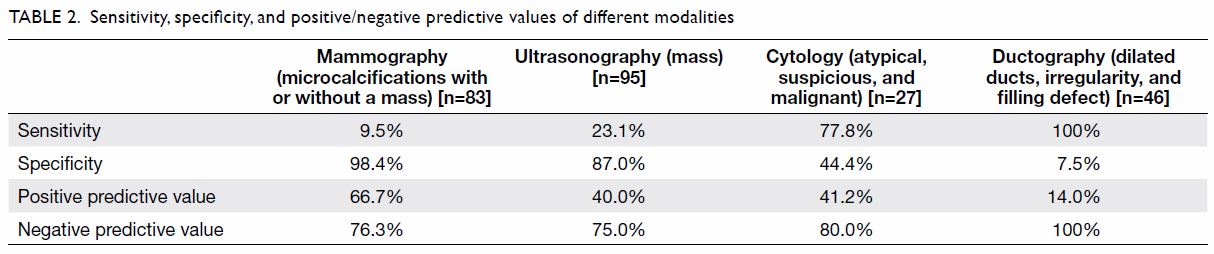

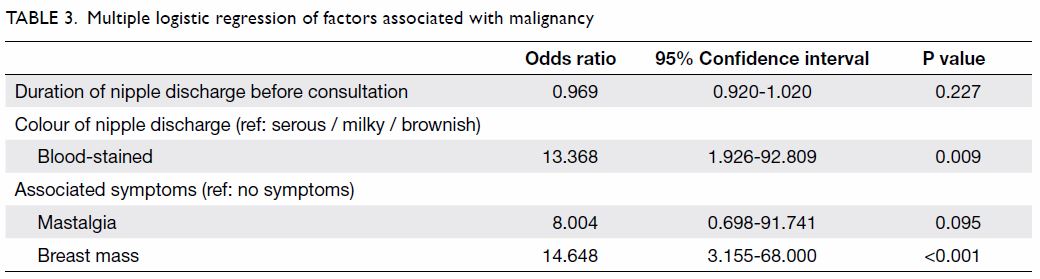

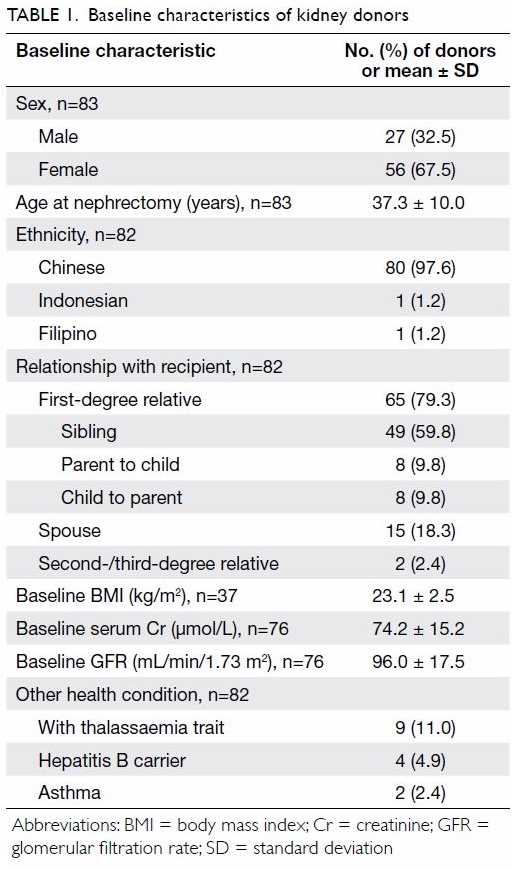

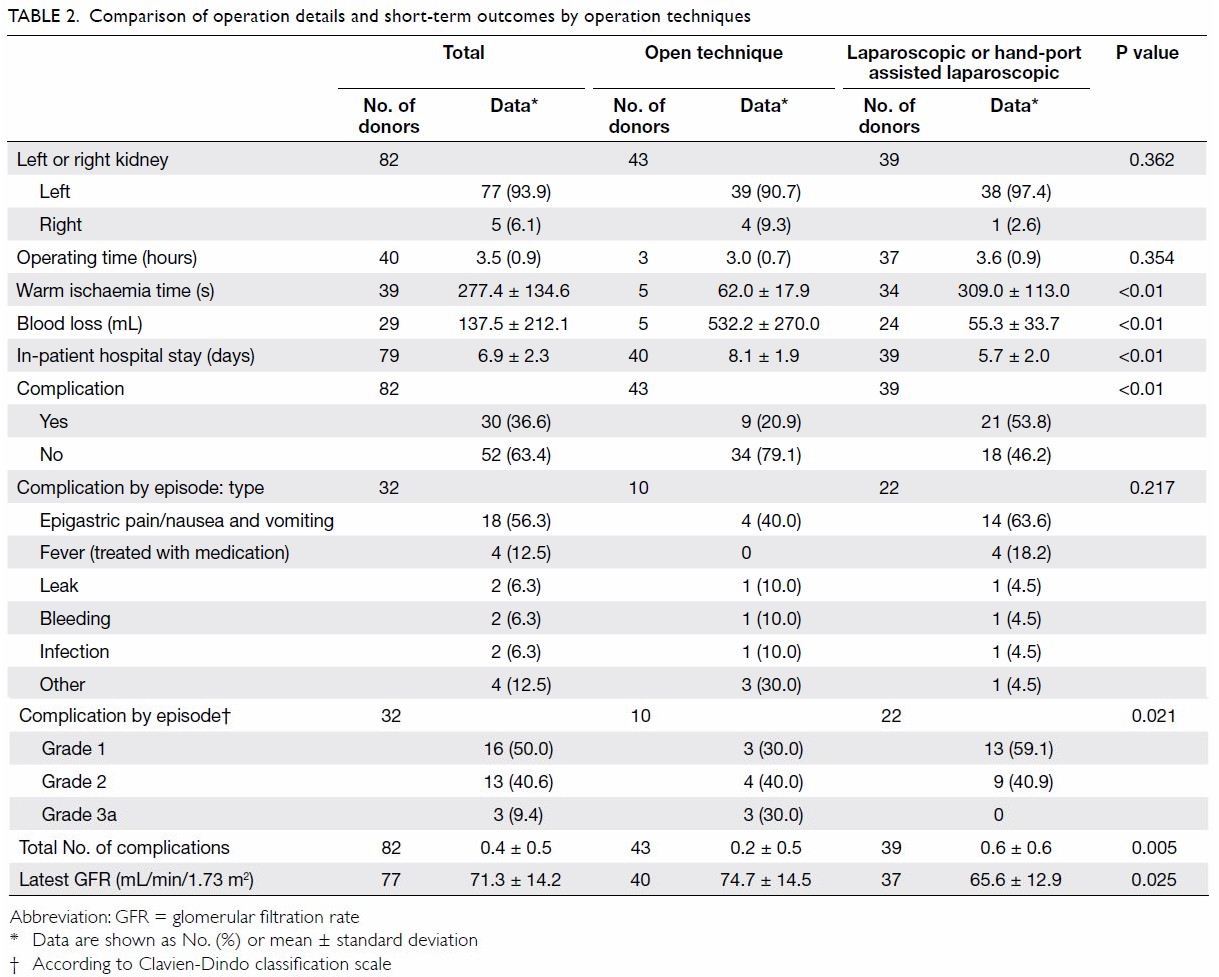

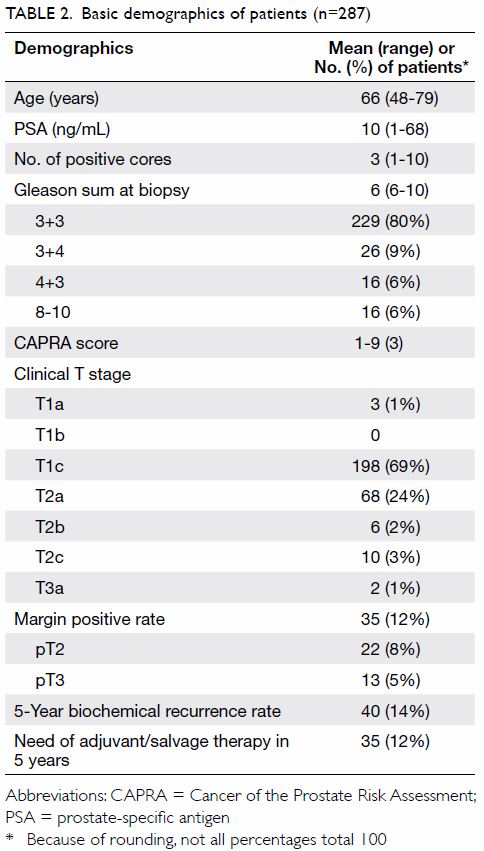

A total of 17 patients with HNCAS were identified

and managed in our institution from December 1997 to September 2016. Their

demographic and clinicopathological information are shown in Table

1. In brief, males predominated and there were only two female

patients. Their median age was 81 years (range, 67-92 years). Only one

patient had a history of whole-scalp RT for a lateral scalp angiosarcoma

more than 10 years ago in another institution. He had a new angiosarcoma

on the opposite side of his scalp that was treated in our centre as a

second primary angiosarcoma induced by past RT. The median duration from

onset of presentation to diagnosis was 4 months (range, 2-33 months).

Patients presented with protean symptoms: bleeding

(n=7), pain (n=4), nodule (n=3), ulceration (n=2), pigmentation (n=2),

pruritus (n=1), and localised oedema (n=1). One patient presented with an

asymptomatic purplish macule but no other symptoms.

The tumours were present in the scalp only (n=11),

face only (n=4), or both scalp and face (n=2). No patient had neck CAS.

Ten patients had a localised/unifocal tumour. Seven patients were

inflicted by multiple/diffuse lesions that were considered inoperable and

treated with palliative intent in four. Of the three remaining patients

with multiple/diffuse lesions, the tumours were still amenable to

potentially curative surgery although two (cases 7 and 15) declined any

treatment initially. Deep invasion occurred in two patients. Of the 11

patients whose tumour dimension had been documented, the median diameter

was 4 cm (range, 3-13 cm). In the other six patients in whom dimensions

were not recorded, there was extensive involvement by the HNCAS.

At the time of diagnosis, the numbers of T1 (≤5 cm)

and T2 (>5 cm) diseases were seven and 10, respectively. Regional nodal

spread was present in six patients. Only two patients (cases 2 and 3) were

found to have distant metastases: lung in one patient, and lung and spine

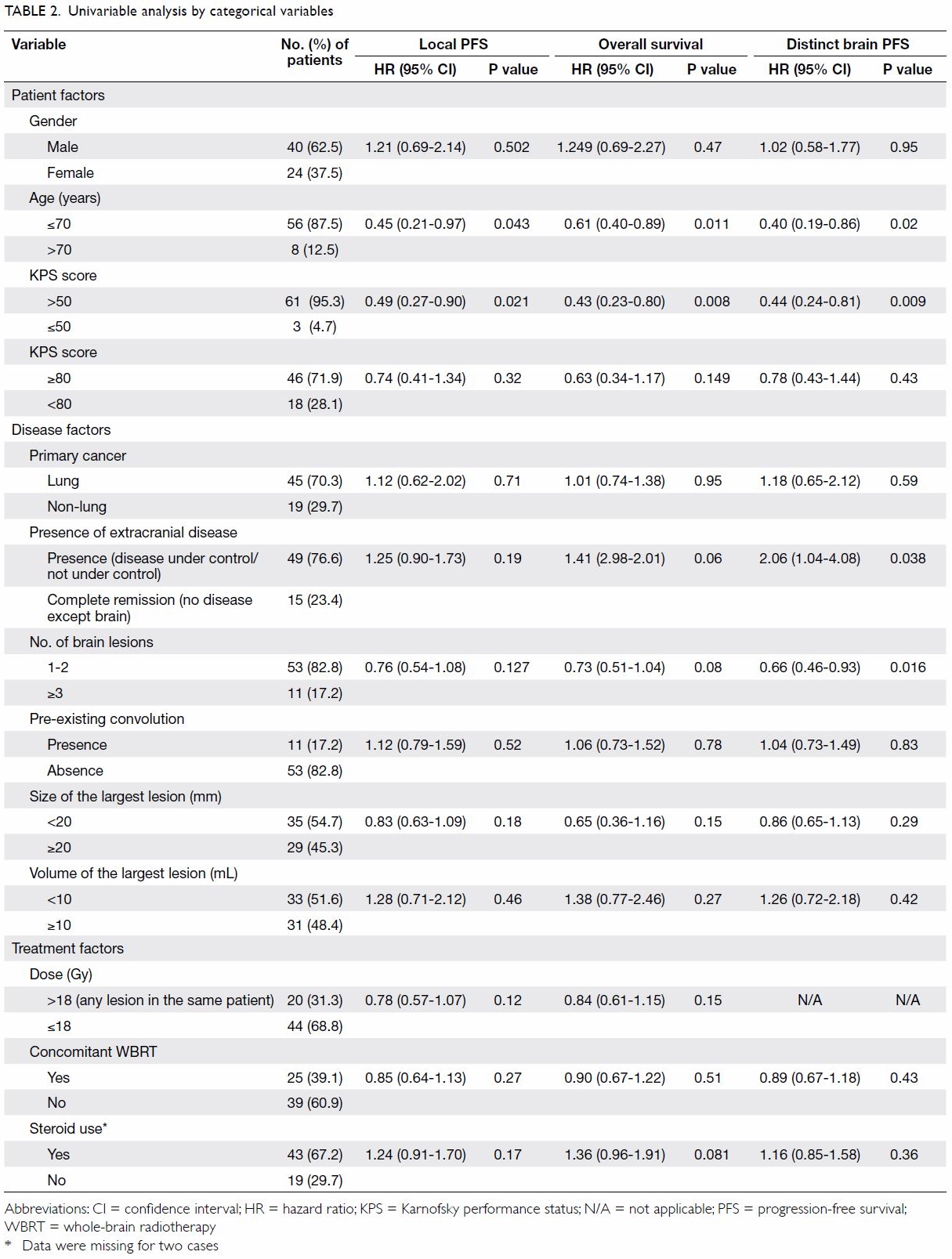

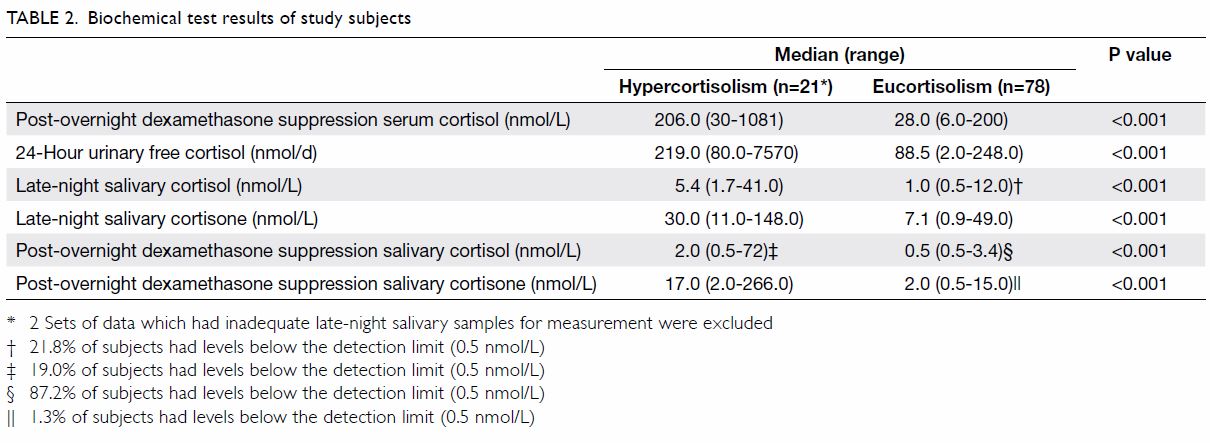

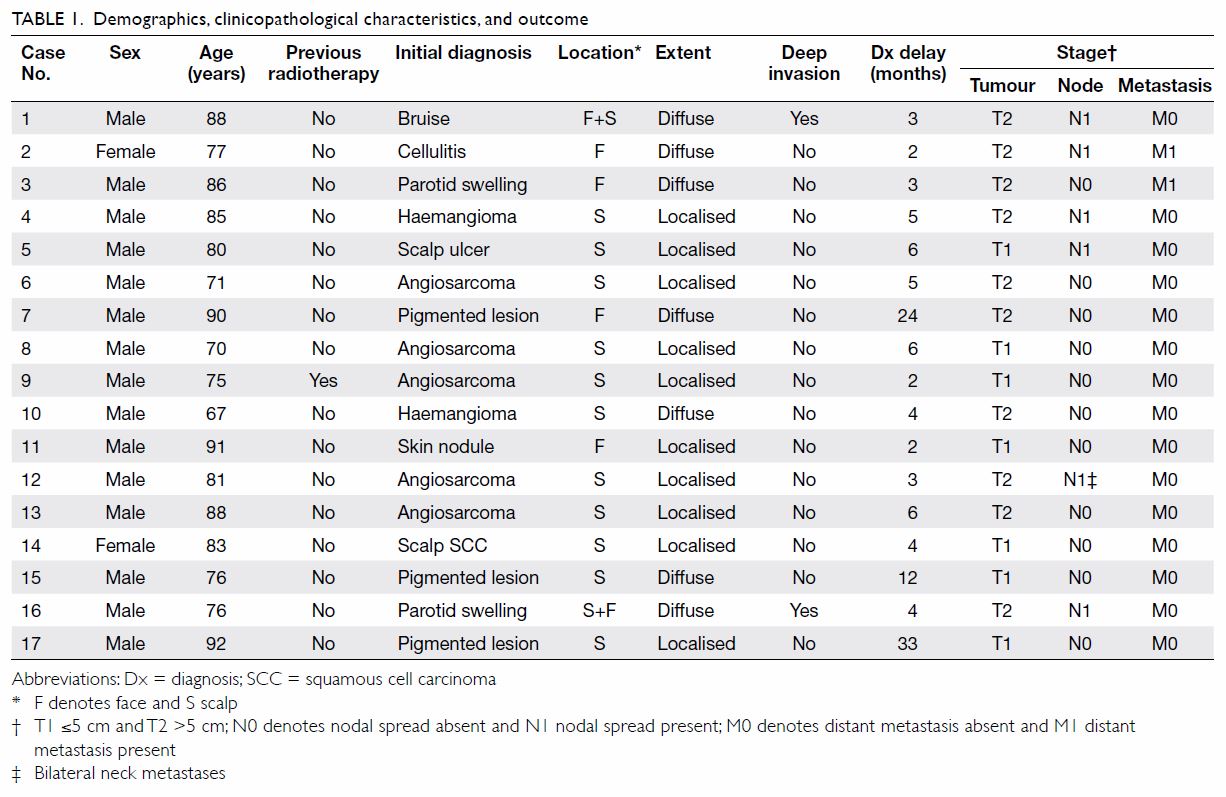

in the other (Table 1). The modalities of therapy were surgery

(n=6), surgery + adjuvant RT (n=1), palliative RT (n=5), and palliative

chemotherapy (n=3; two of them also received palliative RT following

chemotherapy). The remaining two patients (cases 7 and 15) refused any

form of treatment initially (Table 2). Incorporating subsequent therapy, surgery,

RT and chemotherapy were eventually offered to seven, 10, and five

patients, respectively.

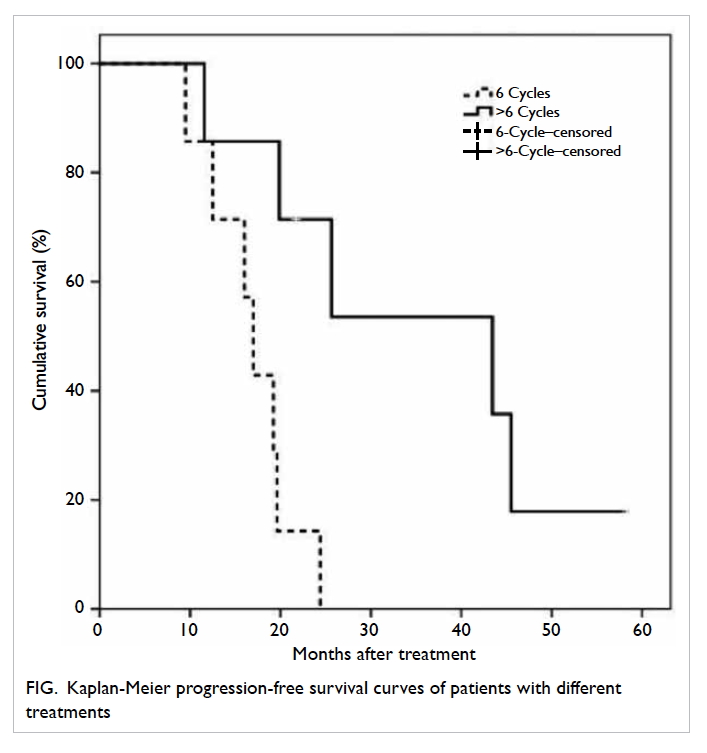

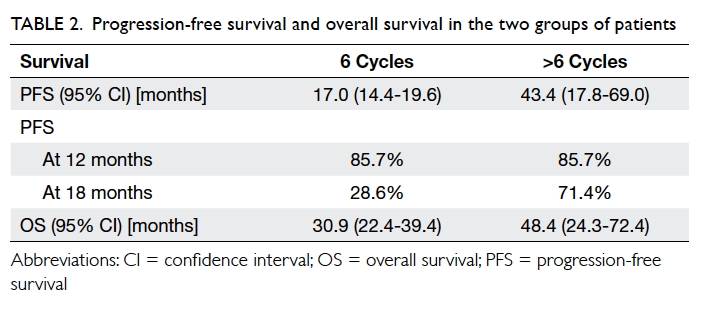

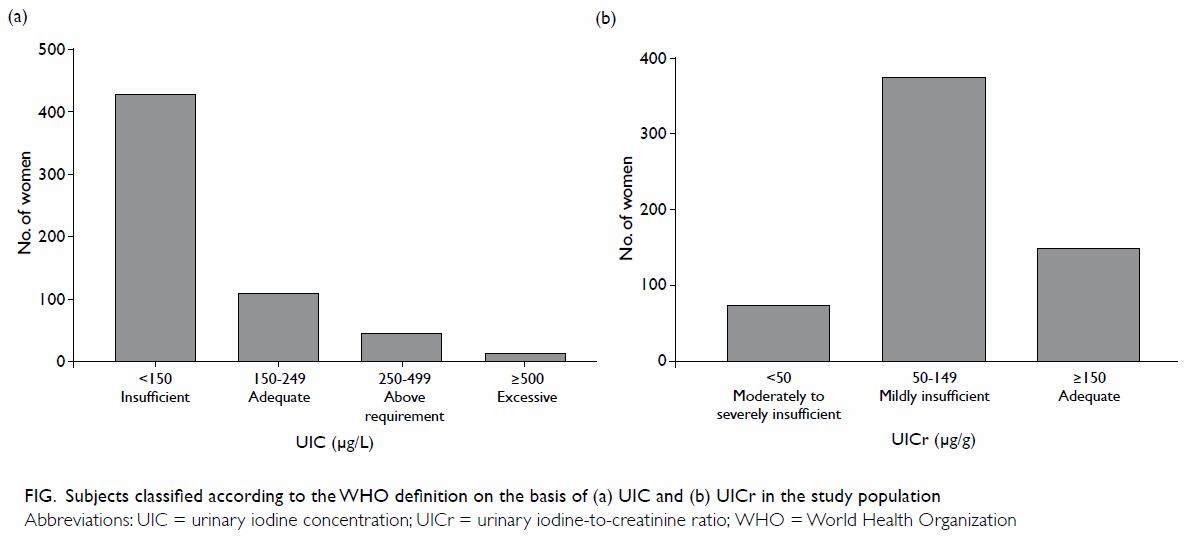

Of the seven patients treated surgically, the

resection margin was positive in two. Tumour recurred in six of them: four

local and two regional recurrences. The median time to relapse was 7.5

months (range, 2-32 months). Overall, 16 patients had died; the causes of

death were HNCAS in 12 and inter-current diseases in four (Table

2). One patient (case 15) was still living with the disease 21

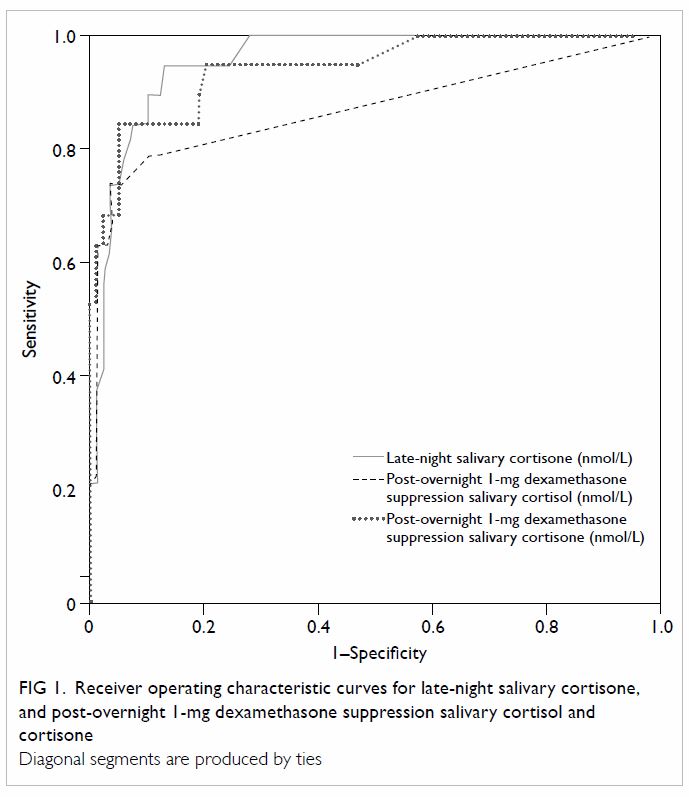

months after diagnosis. The median OS was 11.1 months and the longest OS

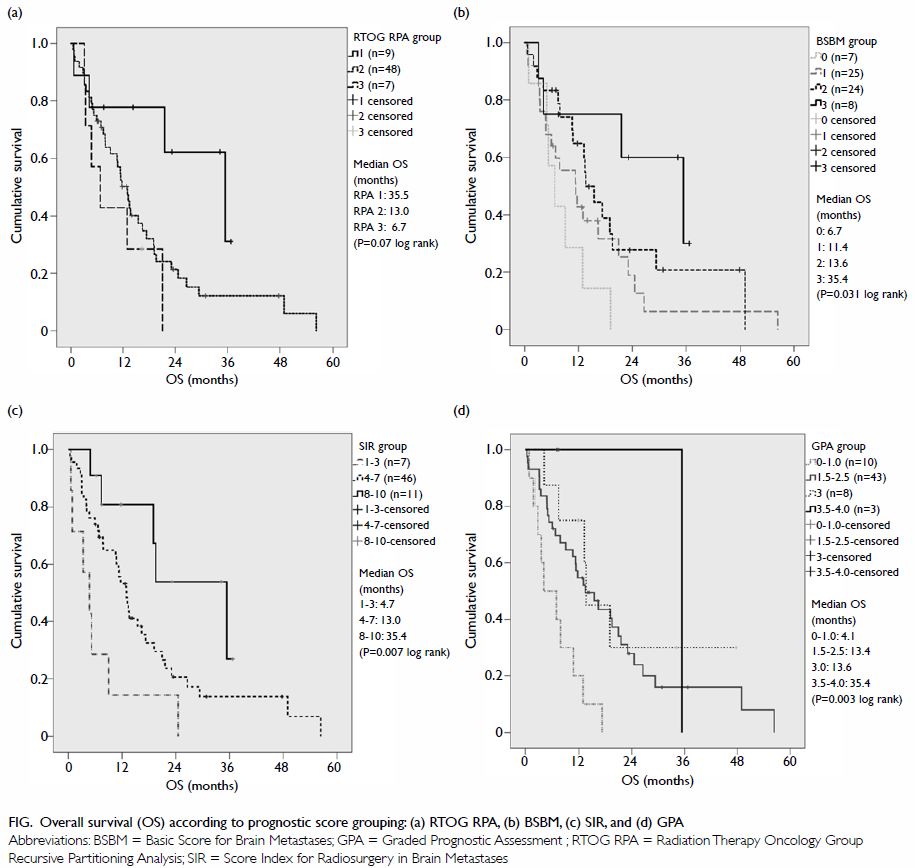

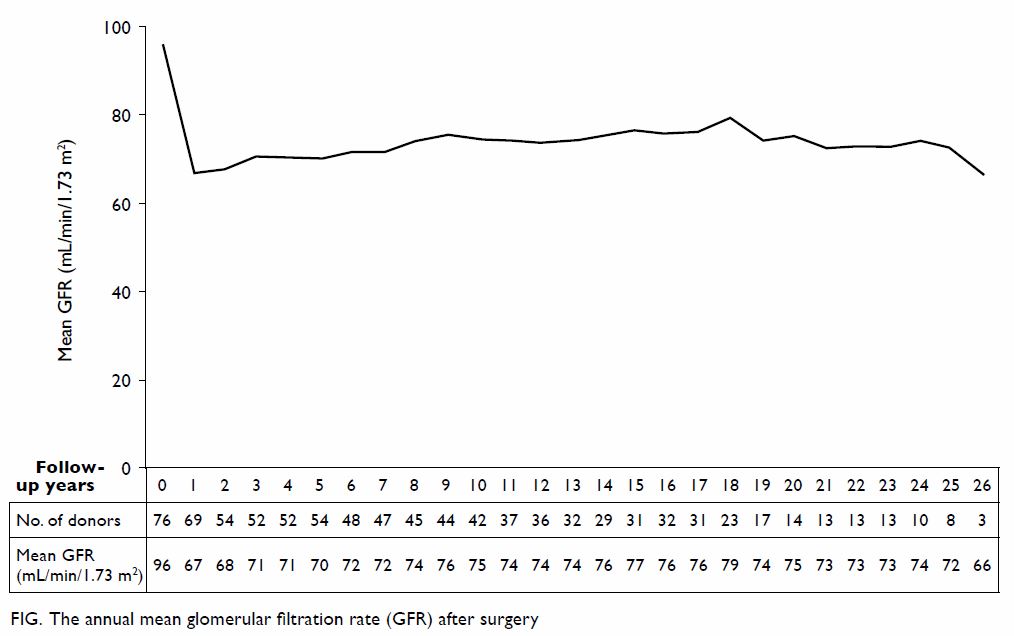

in our series was 42 months (case 6) [Fig 1].

Discussion

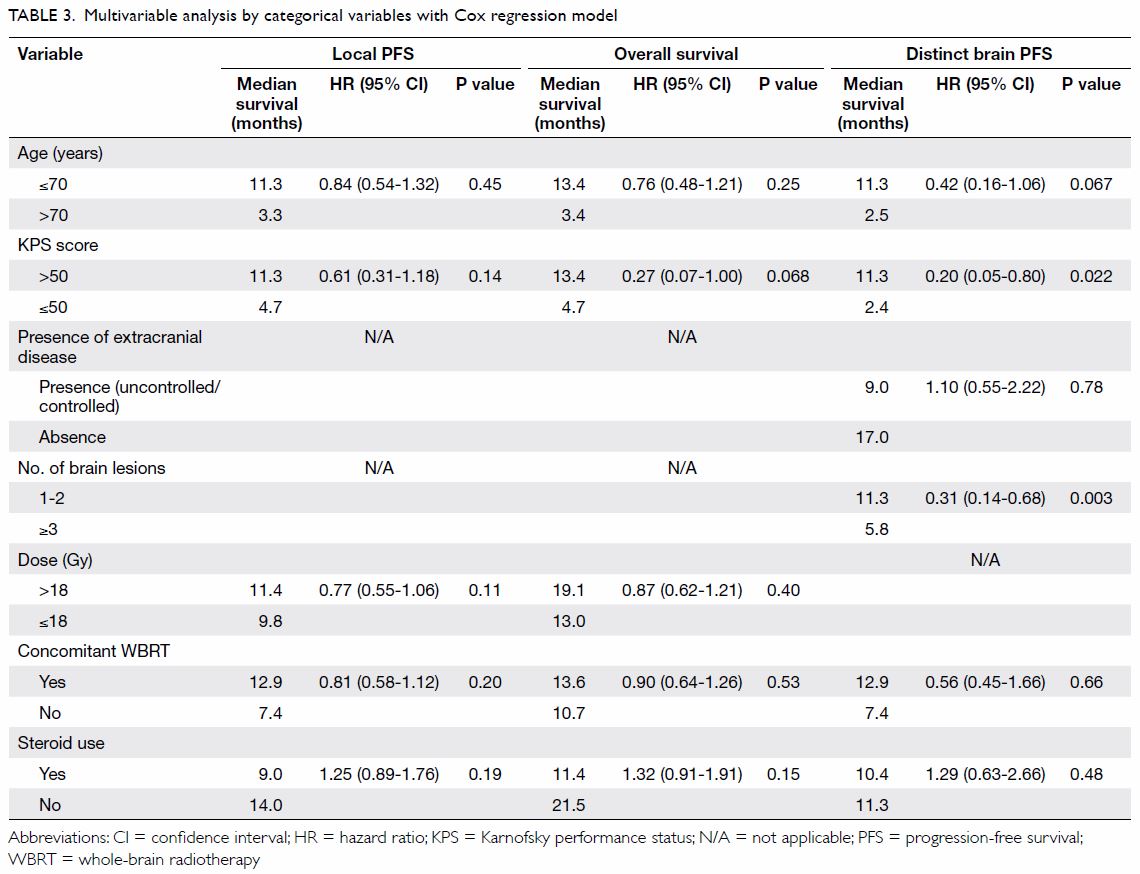

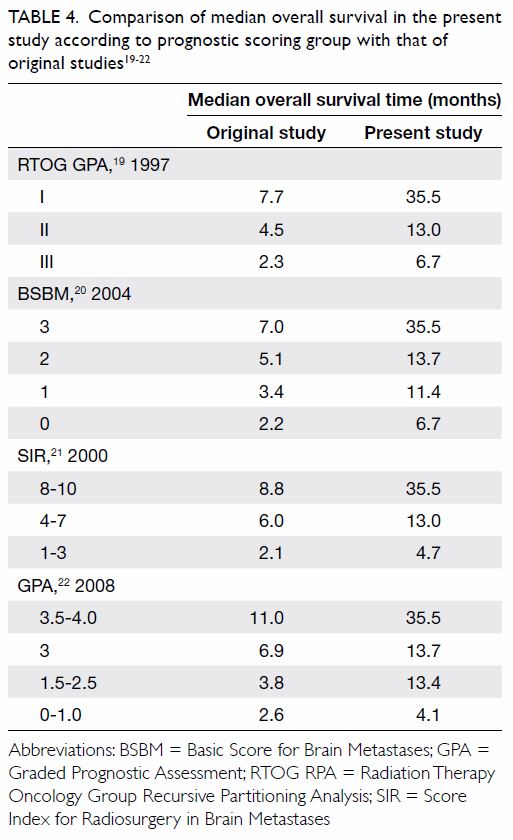

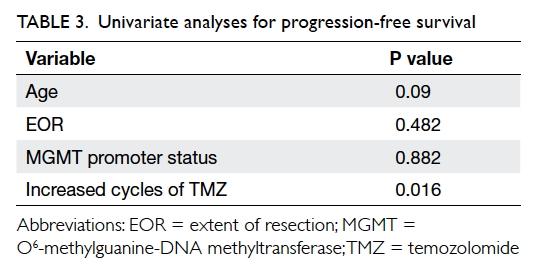

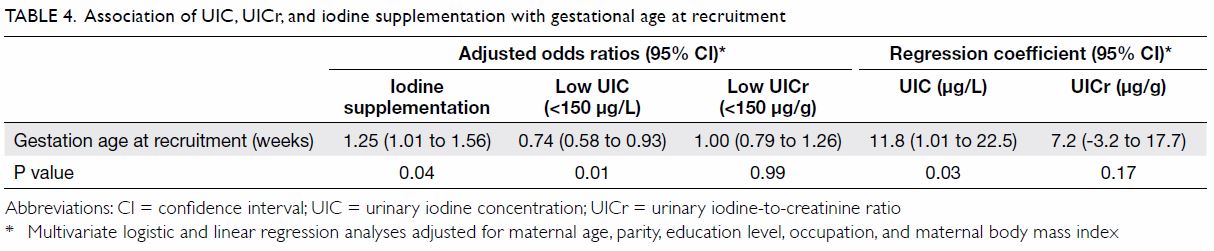

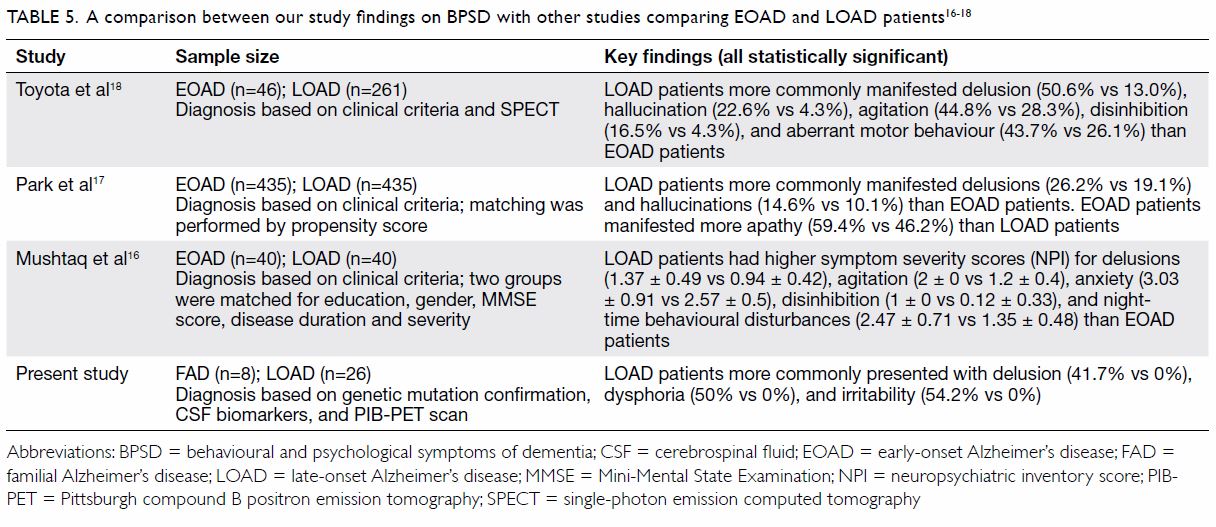

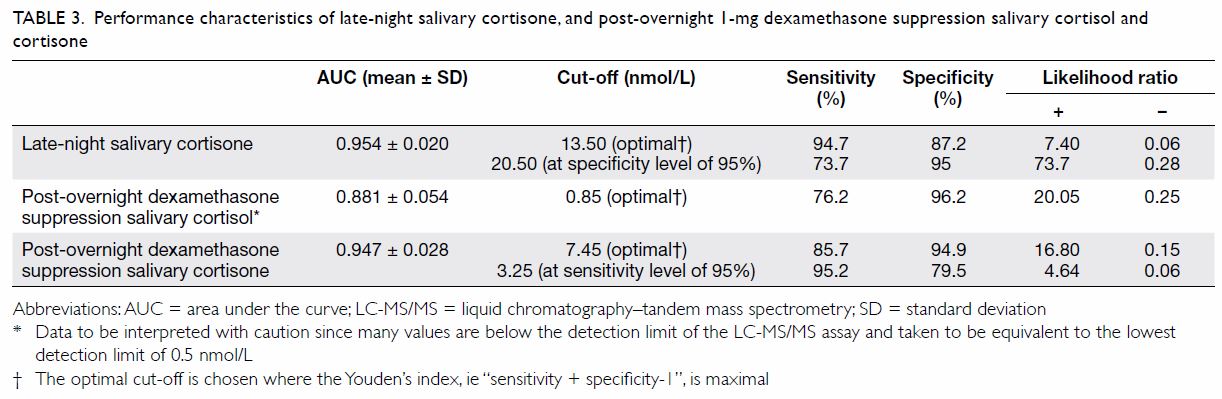

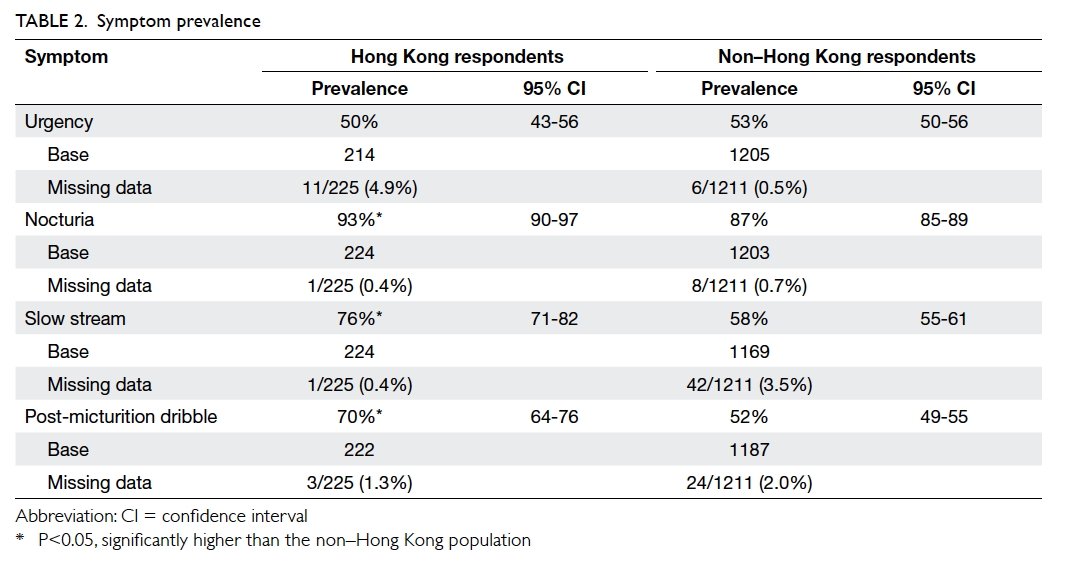

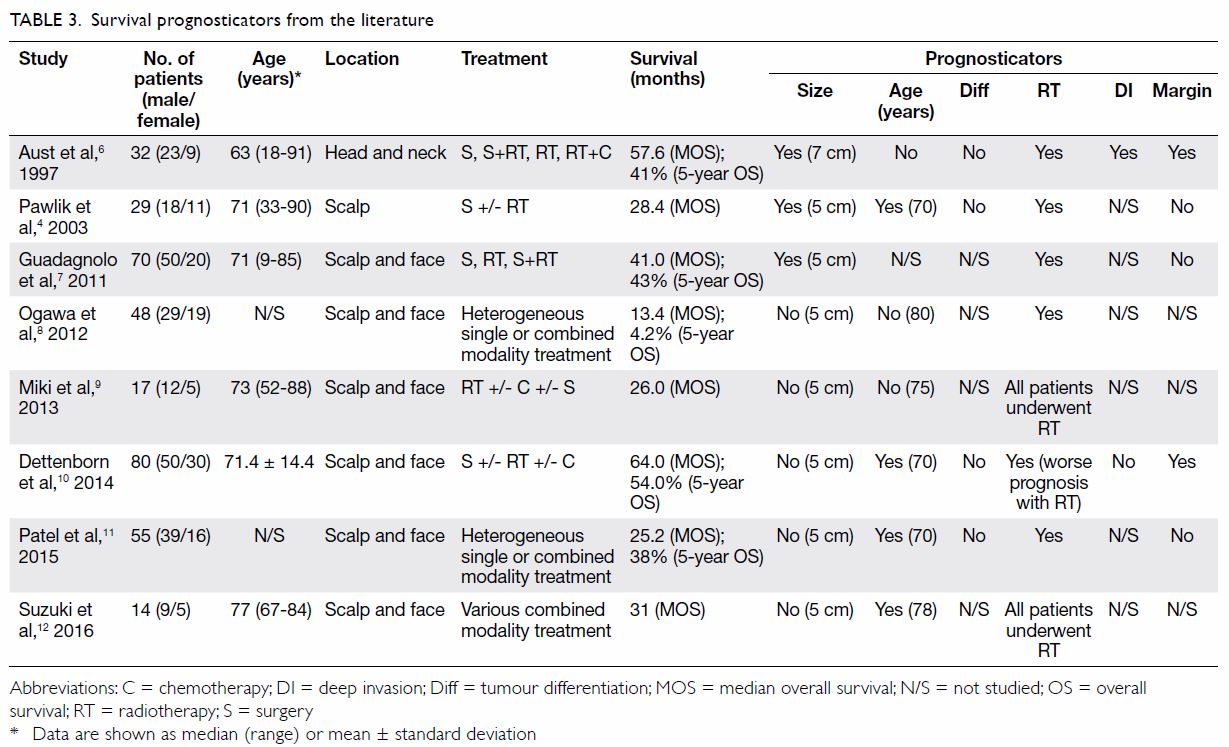

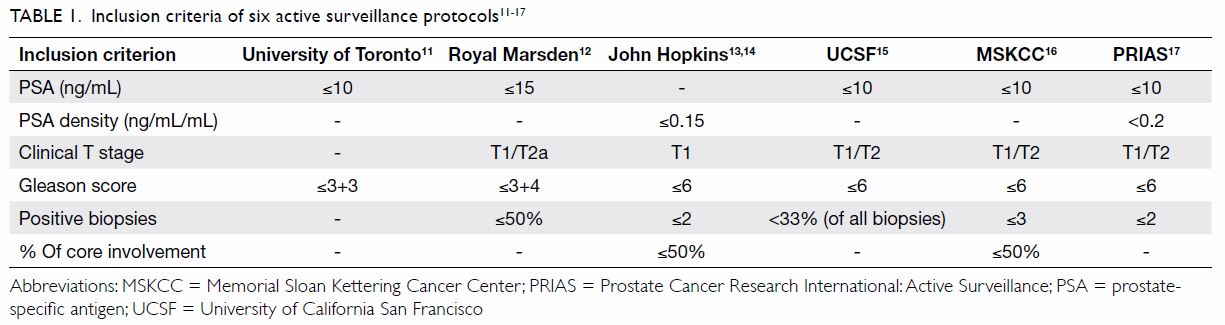

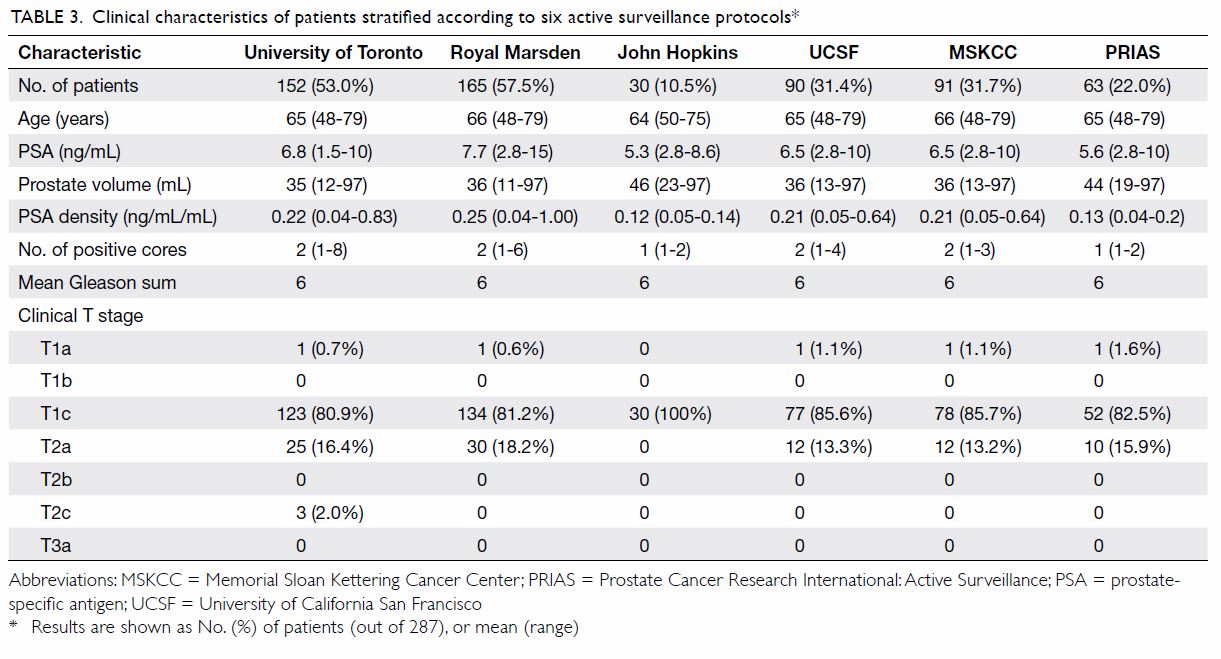

The oncological outcome of this study is obviously

far from satisfactory when compared with a reported median survival of

13.4 to 64 months as shown in Table 3,4 6 7

8 9

10 11

12 which summarises the postulated

prognosticators. Only those studies performed over the past two decades

and that focused on HNCAS with more than 10 cases were included. Patient

age, tumour size, tumour differentiation, deep invasion, and margin status

showed conflicting results. Of note, RT was the most promising and

consistent prognosticator; only one study showed an adverse effect on

survival.10 The disparity might

well be due to selection bias for RT in a retrospective study—more

advanced disease tends to receive adjuvant RT. The evidence lends credence

to adjuvant RT for HNCAS. The suboptimal outcome in our study is

multifactorial: detainment of diagnosis, inclusion of palliative cases for

survival evaluation, advanced age precluding curative treatment, and

unpopular adoption of RT or chemotherapy as multimodal therapy. In this

series, adjuvant RT was administered to only one patient after surgery,

either because others declined RT or wound complications precluded its

application.

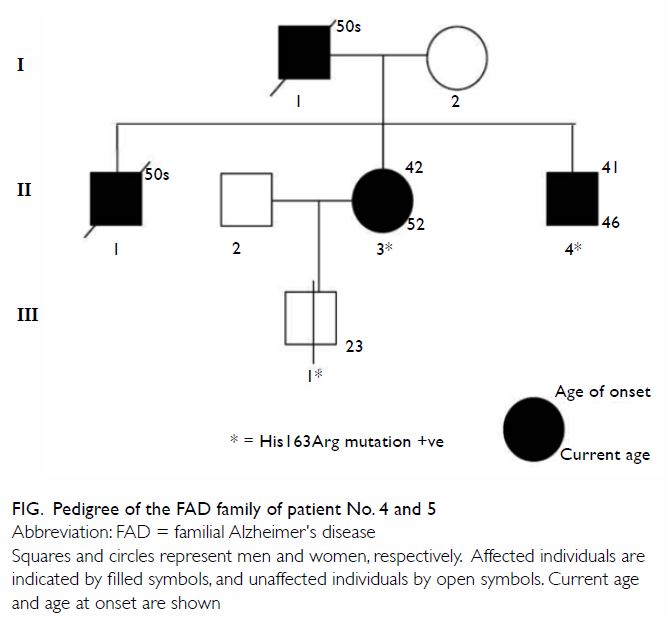

The diagnosis of HNCAS is often late as early

lesions can simulate innocent violaceous macules masquerading as benign

dermatological entities (Fig 2). From our experience, the median duration was

4 months prior to diagnostic confirmation with histopathological

examination. Three of our patients (cases 7, 15, and 17) had their

diagnosis made more than 12 months after onset of disease. The longest

delay was 33 months (case 17) and is absolutely not acceptable.

Interestingly, HNCAS manifested as pigmented lesions in two patients and

thereby misled clinicians in decision making. Increased awareness of this

rare disease by primary care clinicians is essential to expedite patient

referral. For specialists, a low threshold to biopsy of newly developed

purplish skin lesions in the elderly patients is pivotal to an early

diagnosis.

In our series, patients who underwent palliative

therapy were included in the OS calculation and this might have partially

contributed to our poor results. This was echoed by Buschmann et al13 who also included patients with palliative resection

in outcome evaluation; their longest survival reported was 36 months. This

is similar to our experience where longest survival was 42 months.

Conversely, Dettenborn et al10

reported 80 patients with HNCAS treated surgically (44 patients also

received postoperative RT) with curative intent and 5-year OS of 54% and

median OS of 64 months. Similarly, Suzuki et al12

described their experience of definitive RT as the principal curative

treatment for HNCAS; a median OS survival of 31 months was attained.

Nonetheless, the results of RT were compromised when palliative cases were

incorporated: only 12% of patients survived more than 5 years in one

study.14

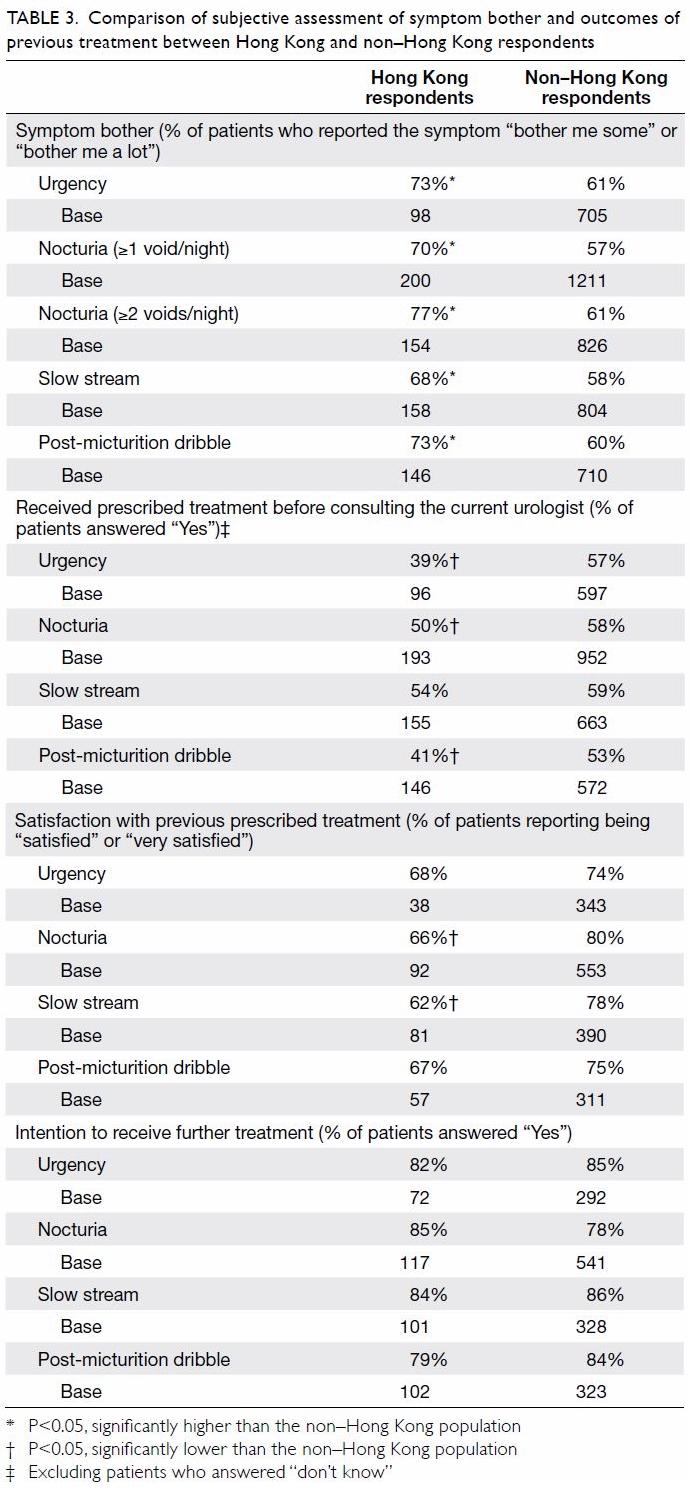

Our patients were older (median age, 81 years) than

those reported in the literature (median age, 63-77 years) [Table

3]. The prognostic significance of age on the outcome of HNCAS is

controversial. Patel et al11

reported that patients younger than 70 years fared better with improved

locoregional control and relapse-free survival than older patients.

Although age is not a confirmed prognostic factor, advanced age often

precludes patients from curative therapy due to concomitant chronic

diseases or general debility. The elderly patients are also prone to dying

of other disease as encountered in this series; four patients died of

inter-current illnesses (Table 2). Nonetheless, effective systemic treatments

can be well tolerated by some elderly patients with HNCAS. With

taxane-based regimens, a response rate of 83% (10 out of 12 patients) was

achieved and the progression-free survival was approximately 7 months.15

Surgery is historically the main treatment for

HNCAS. The latest approach to optimal management of HNCAS is combined

treatment encompassing surgery, RT, or chemotherapy. Adjuvant RT should be

liberally offered to maximise the oncological outcomes following surgery.

As shown in Table 3, five of six studies support the beneficial

role of RT.4 6 7 8 10 11 Guadagnolo et al7

advocated simple resection of the gross tumour to facilitate

non-complicated reconstruction and thus expedite RT. Two-staged surgery

was discouraged. The resection margin status was not critical to survival

if timely adjuvant RT was administered. From their experience, the 5-year

OS was 43% and 5-year disease-specific survival was 46%. In a review

article, Hwang et al16 also

concluded that positive margin was common (64%) but did not impair the

ultimate outcome. They recommended that surgeons should not be too

obsessive about removing each and every cancer cell if RT was to be

pursued.

Definitive treatment with RT and/or chemotherapy

has also been reported to be effective for HNCAS.9

Of 17 patients treated in that study, complete and partial responses were

accomplished in none and five patients, respectively. The median OS was 26

months. Multimodality treatment in various combinations with surgery, RT,

and chemotherapy has been asserted by Patel et al11

to be effective in improving locoregional control, relapse-free survival,

and OS. In another study, survival (37 months) following combined therapy

(RT and chemotherapy) was better than either modality alone: 23 months for

RT and 15 months for chemotherapy.16

Docetaxel is the preferred agent due to its antiangiogenic and

radio-sensitising effects.9 Other

agents have also been successfully used and include doxorubicin,

ifosfamide, bevacizumab, and interleukin-2. Systemic treatment may be used

in a neoadjuvant setting, adjuvant setting, and as concurrent treatment

with RT.8 17 18

Conversely, RT plus chemotherapy was not shown to have any prognostic

value in a meta-analysis by Shin et al.19

Further studies should be carried out to elucidate the benefit of combined

modality treatment.

Ip and Lee20

reported a smaller local series of CAS that was not confined to the head

and neck. A total of seven patients were enrolled from three clinics of

the Social Hygiene Service in Hong Kong. Only six patients had HNCAS.

Similarly, poor prognosis was demonstrated in these patients. Our bigger

series focusing on HNCAS provides a more updated and detailed strategy for

the management of this rare disease in ethnic Chinese.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample

size was small as only 17 patients were included for evaluation.

Nevertheless it is the largest series reported in our locality. The study

spanned over 19 years (December 1997 to September 2016) and treatment has

evolved over this period. Moreover, like many retrospective series, recall

bias or selection bias are inherent limitations. Patient symptoms, signs,

presentation duration, and criteria for treatment might not be completely

accurate.

Conclusion

We present the first report of HNCAS in ethnic

Chinese. The oncological outcome is far from satisfactory. A high index of

suspicion is mandatory for prompt diagnosis of early disease. Adjuvant RT,

as supported by evidence from the literature, is recommended following

surgery that should aim at gross tumour extirpation to ensure uneventful

reconstruction as well as timely implementation of RT. The benefit and

role of systemic treatment in various combinations with surgery or RT

require further study.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

References

1. Mark RJ, Poen JC, Tran LM, Fu YS,

Juillard GF. Angiosarcoma. A report of 67 patients and a review of the

literature. Cancer 1996;77:2400-6. Crossref

2. Perez MC, Padhya TA, Messina JL, et al.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol

2013;20:3391-7. Crossref

3. Sasaki R, Soejima T, Kishi K, et al.

Angiosarcoma treated with radiotherapy: impact of tumor type and size on

outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:1032-40. Crossref

4. Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, Mcgini CJ, et al.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer

2003;98:1716-26. Crossref

5. Chow TL, Chan TT, Chow TK, Fung SC, Lam

SH. Reconstruction with submental flap for aggressive orofacial cancer.

Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120:431-6. Crossref

6. Aust MR, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, et al.

Angiosarcoma of the head and neck: clinical and pathologic

characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997;106:943-51. Crossref

7. Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Araujo D, Ravi

V, Shellenberger TD, Sturgis EM. Outcomes after definitive treatment for

cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Head Neck 2011;33:661-7. Crossref

8. Ogawa K, Takahashi K, Asato Y, et al.

Treatment and prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: a

retrospective analysis of 48 patients. Br J Radiol 2012;85:e1127-33. Crossref

9. Miki Y, Tada T, Kamo R, et al. Single

institutional experience of the treatment of angiosarcoma of the face and

scalp. Br J Radiol 2013;86:20130439. Crossref

10. Dettenborn T, Wermker K, Schulze HJ,

Klein M, Schwipper V, Hallermann C. Prognostic features in angiosarcoma of

the head and neck: a retrospective monocenter study. J Craniomaxillofac

Surg 2014;42:1623-8. Crossref

11. Patel SH, Hayden RE, Hinni ML, et al.

Angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: the Mayo Clinic experience. JAMA

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:335-40. Crossref

12. Suzuki G, Yamazaki H, Takenaka H, et

al. Definitive radiation therapy for angiosarcoma of the face and scalp.

In Vivo 2016;30:921-6.Crossref

13. Buschmann A, Lehnhardt M, Toman N,

Preiler P, Salakdeh MS, Muehlberger T. Surgical treatment of angiosarcoma

of the scalp: less is more. Ann Plast Surg 2008;61:399-403. Crossref

14. Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW.

Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer

1987;59:1046-57. Crossref

15. Letsa I, Benson C, Al-Muderis O,

Judson I. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp: effective systemic treatment

in the older population. J Geriatr Oncol 2014;5:276-80. Crossref

16. Hwang K, Kim MY, Lee SH.

Recommendations for therapeutic decisions of angiosarcoma of the scalp and

face. J Craniofac Surg 2015;26:e253-6. Crossref

17. Wollina U, Fuller J, Graefe T, Kaatz

M, Lopatta E. Angiosarcoma of the scalp: treatment with liposomal

doxorubicin and radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2001;127:396-9. Crossref

18. Yang P, Zhu Q, Jiang F. Combination

therapy for scalp angiosarcoma using bevacizumab and chemotherapy: a case

report and review literature. Chin J Cancer Res 2013;25:358-61.

19. Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, Yang KM.

Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and

face: systemic review and meta-analysis. Head neck 2017;39:380-6. Crossref

20. Ip FC, Lee CK. Cutaneous angiosarcoma:

a case series in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol 2010;18:6-14.

A video clip showing frameless

stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases is available at

A video clip showing frameless

stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases is available at