Hong Kong Med J 2017 Oct;23(5):480–8 | Epub 25 Aug 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166143

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Occupational stress and burnout among Hong Kong dentists

HB Choy, MGD (CDSHK), MRACDS (GDP)1;

May CM Wong, MPhil, PhD2

1 Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery, Caritas Medical Centre,

Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

2 Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr May CM Wong (mcmwong@hku.hk)

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 94th General Session

& Exhibition of the IADR, 3rd Meeting of the IADR Asia Pacific Region and

35th Annual Meeting of the IADR Korean Division held in Seoul, Korea on

22-25 June 2016.

Abstract

Introduction: Professional burnout has been

described as a gradual erosion of a person and may

be one of the possible consequences of chronic

occupational stress. Although occupational stress

has been surveyed among dentists in Hong Kong,

no study has been published about burnout in the

profession. This study aimed to evaluate burnout

among Hong Kong dentists and its association with

occupational stress.

Methods: We surveyed a random sample of 1086

registered dentists in Hong Kong, which formed

50% of the local profession. They were mailed

an anonymous questionnaire about burnout and

occupational stress in 2015. The questionnaire

assessed occupational stress, coping strategies,

effects of stress, level of burnout, and socio-demographic

characteristics of the respondents.

Occupational stress assessment concerned 33

stressors in five groups: patient-related, time-related,

income-related, job-related, and staff-/technically

related. Level of burnout was assessed by the Maslach

Burnout Inventory–Human Services Survey (22

items) with three scores: emotional exhaustion,

depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment.

Results: Completed questionnaires were received

from 301 dentists (response rate, 28.3%), of whom

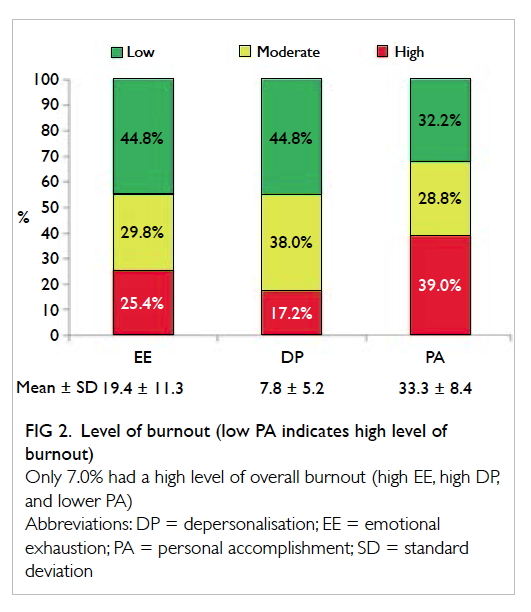

25.4% had a high level of emotional exhaustion,

17.2% had a high level of depersonalisation, and 39.0% had a low level of personal accomplishment.

Only 7.0% of respondents, however, had a high

level of overall burnout (high emotional exhaustion,

high depersonalisation, and low personal

accomplishment). A high level of overall burnout

was significantly associated with a higher mean score

for job-related stressors and lack of postgraduate

qualifications (P<0.05).

Conclusions: Patient-related stressors are the top

occupational stressors experienced by dentists in

Hong Kong. In spite of this, a low proportion of

dentists have a high level of overall burnout. There

was a positive association between occupational

stress and level of burnout.

New knowledge added by this study

- Approximately 7.0% of Hong Kong dentists have a high level of overall burnout.

- Job-related stressors and postgraduate qualifications are associated with a high level of overall burnout.

- Although only a low proportion of Hong Kong dentists has high overall burnout, this issue should not be overlooked. Dentistry is quite a lonely profession. Peer support and sharing is important for the development of dentistry in Hong Kong.

- Dentists are advised to update their knowledge and skills to meet the increasing expectations and challenges from patients and the society.

Introduction

Professional burnout can be one of the possible

consequences of chronic occupational stress.1

Burnout has been described as a gradual erosion

of the person and comprises three characteristics.2

First, the individuals are exhausted, either

mentally or emotionally.2 They feel drained, tired

with insufficient energy, and are unable to cope.3

Second, they may have a negative, indifferent,

or cynical attitude towards patients, clients, or

colleagues.2 They feel numb about work and distance

themselves emotionally.3 Finally, they also tend to

feel dissatisfied with their own performance and

evaluate themselves negatively.2 They find difficulty

in concentrating on their work and caring about

their families.3 The consequences of burnout can be

very serious. Maslach and Jackson4 found that the

quality of care and service provided by individuals

who have burnout syndrome may be substandard.

Burnout has also been found to be associated with

job turnover, absenteeism, low morale, and personal

dysfunction.3 Maslach and her colleague5 6 have

studied the burnout syndrome for many years and

devised a measurement tool—the Maslach Burnout

Inventory—Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS).4 7 Although some studies of burnout have been

conducted among dentists using the MBI-HSS,1 8 9 10

most studies on stress and burnout in health

professions have focused on physicians11 12 13and

nurses.14 15

In 2001, a survey was conducted to investigate

the sources of occupation stress among dentists in

Hong Kong.16 There has been no published study on

burnout among dentists in Hong Kong since then.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to investigate

the burnout among dentists in Hong Kong and

the association between occupational stress and

burnout. The objectives of our study were to identify

the occupational stressors and the prevalence of

burnout among dentists in Hong Kong and their

association.

Methods

Survey design and sample

In October 2015, there were 2173 locally registered

dentists working in Hong Kong according to the

Dental Council of Hong Kong.17 In order to achieve

the width of the 95% confidence interval (CI)

calculated from the sample proportion estimates

of burnout outcomes no wider than ± 5%, a sample

of 384 dentists was needed (using a conservative

assumption of sample proportions to be 50%).

Taking into account the low response rate (<40%)

achieved by previous surveys in Hong Kong,

50% of the dentists were systematically randomly

sampled (with a random start of ‘2’ generated from

Excel) from the published list of registered dentists

according to their family names and a sample size of

1086 was chosen. The questionnaires were mailed in

sealed envelopes in early November 2015 along with

a stamped, self-addressed envelope. The participants

were assured of confidentiality. No names and

addresses were asked for and no codes were

marked on the questionnaires or return envelopes.

Questionnaires for selected government dentists

were sent collectively to the Department of Health

and delivered internally. Reminders were sent to all

selected private dentists in late November or early

December 2015. Participants did not receive any

specific incentive to complete this survey.

Construction of questionnaire

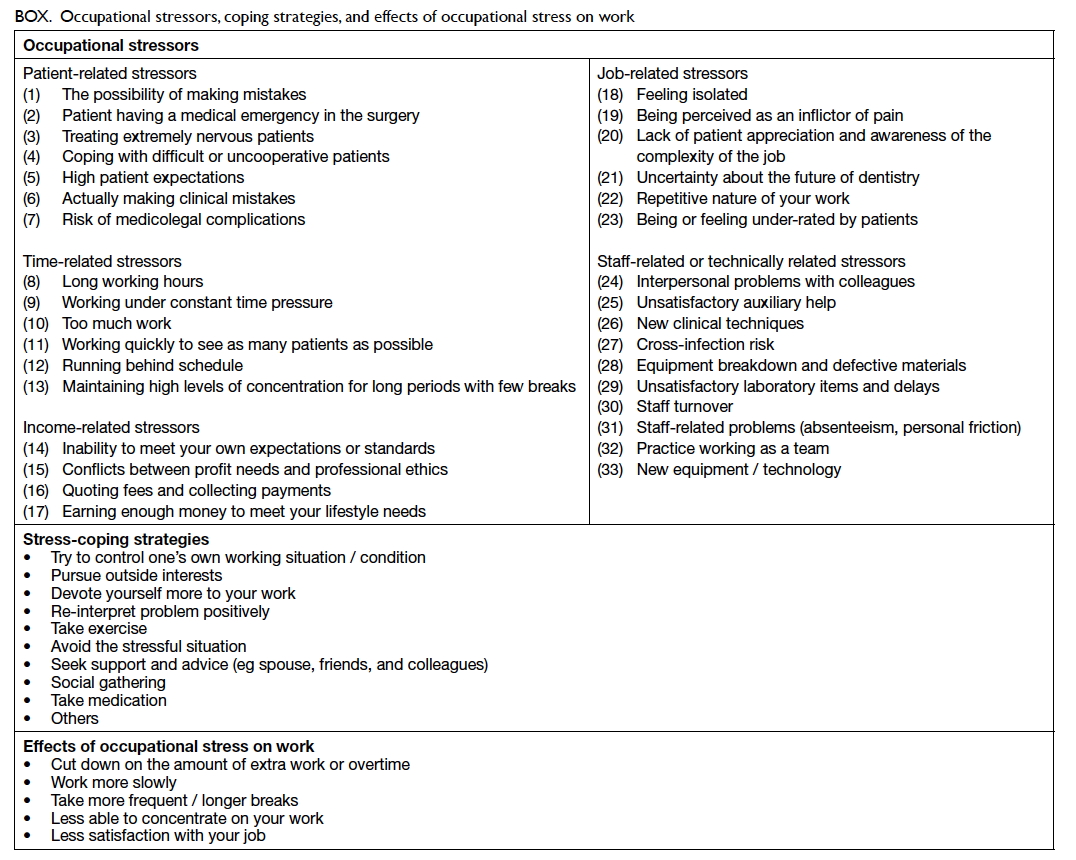

The questionnaire assessed the sources of

occupational stress, stress-coping strategies, effects

of stress on work, level of burnout, and socio-demographic

characteristics of the study subjects.

There were 33 occupational stressors for identifying

the sources of stress; 26 of which were proposed by

Cooper et al.18 An additional seven stressors were

proposed by Waddington.19 Participants were asked

to rate the level of stress they experienced on a

5-point scale ranging from ‘1 = No stress’ to ‘5 = A

great deal of stress’. The 33 stressors were grouped

into five domains: patient-related, time-related,

income-related, job-related, and staff-related or

technically related (Box). Based on the work by

Cooper et al,18 10 stress-coping strategies of dentists

were included. Participants were asked how often

they would use these stress-coping strategies with

responses categorised on a 5-point scale ranging

from ‘1 = Never’ to ‘5 = Always’ (Box). Based on

the work of Kopec and Esdaile,20 five effects of

occupational stress on work were included with

responses rated on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘1 =

Not at all’ to ‘4 = A lot’ (Box). Of note, MBI-HSS,7

which has been recognised as the leading measure of

burnout, was also included and consisted of 22 items

with responses rated on a 7-point scale ranging from

‘0 = Never’ to ‘6 = Every day’. The MBI-HSS addressed

three general scales: emotional exhaustion (EE; 9

items with score range of 0-54) measuring the feelings

of being emotionally overextended and exhausted

by one’s work; depersonalisation (DP; 5 items with

score range of 0-30) measuring the unfeeling and

impersonal response towards recipients of one’s

service, care treatment, or instruction; and personal

accomplishment (PA; 8 items with score range of

0-48) measuring the feelings of competence and

successful achievement in one’s work. Personal

information about the participants was also collected

and included their age, gender, years of practice,

type of practice, location, hours of work per week,

marital status, working status of spouse, number of

children, religious beliefs, whether the participant

had postgraduate qualifications, and whether the

participant was a specialist.

The Institutional Review Board of The

University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong

Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB, reference

number: UW 15-524) approved the study prior to

distribution of the questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

The mean score for each stressor group was calculated

and ranked. Three subscale scores of MBI-HSS (EE,

DP, and PA) were calculated and subjects categorised

into one of the three groups—high, moderate, or low

level of burnout. Those with EE score of ≥27 were

considered to have high EE level, 17-26 moderate

and 0-16 low level. Those with DP score of ≥13 were

considered to have high DP level, 7-12 moderate

and 0-6 low level. Those with PA score of ≤31 were

considered to have low PA level, 32-38 moderate

and ≥39 high level. Subjects with high EE, high DP,

and low PA levels simultaneously were considered

to have a high level of overall burnout. Others were

considered to have low overall burnout. Of the

results, 95% CIs were computed as well.

The relationships between EE, DP and PA

scores, and the set of 17 independent variables (12

demographic variables and the five stressor group

scores) were analysed by analysis of covariance

(ANCOVA). A forward selection method was

adopted. In this approach, independent variables

were added into the model one at a time. In each

step, each variable that was not already in the model

was tested for inclusion in the model. The most

significant of these variables was added to the model.

Finally, only significant variables were selected in the

final model.

The relationship between levels of overall

burnout (high and low) and the set of 17 independent

variables was analysed by multiple logistic regression.

A forward selection method was adopted as well. All

analyses were performed using the SPSS (Windows

version 22.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US) and the

level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Response

A total of 1086 questionnaires were sent to the

randomly selected dentists. Reminders were sent

to the selected private dentists 2 to 4 weeks later.

We received 301 completed questionnaires and 22

questionnaires returned undelivered by the post

office, resulting in a response rate of 28.3% (301/[1086–22] x 100%).

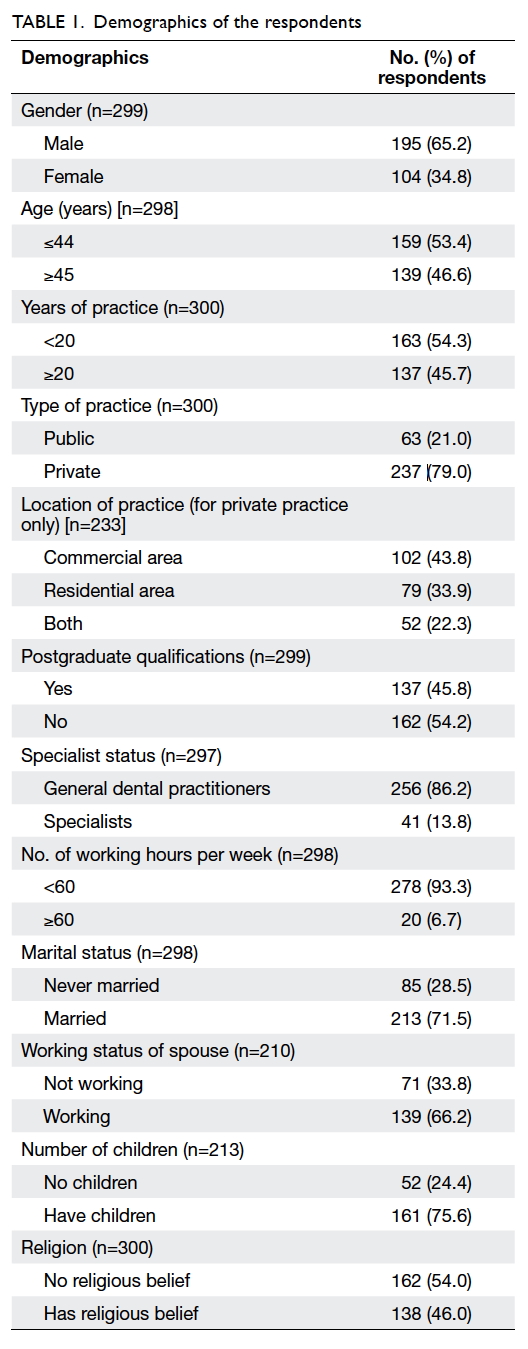

Demographics

The demographics of the respondents are shown

in Table 1. Approximately 65% of the respondents

were male and 79% worked in the private sector

that also included non-governmental organisations.

Approximately 46% of dentists had acquired one or

more postgraduate qualifications. More than 86% of

the respondents were general dental practitioners.

Over a quarter (29%) had never married and more

than half (54%) claimed to have no religious beliefs.

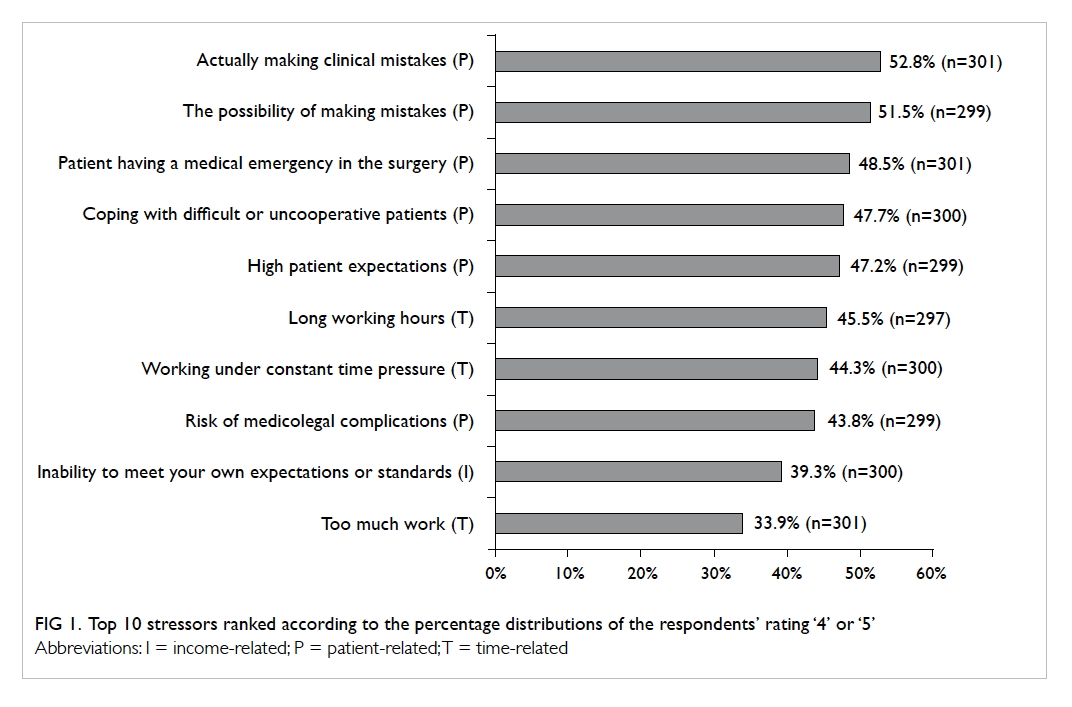

Occupational stress

The top 10 stressors according to the percentage

distribution of the respondents’ ratings ‘4’ or ‘5’

(considered to be high level) are shown in Figure 1. Six of the top 10 highest ranked stressors (and

actually the top five highest ranked) were patient-related

stressors and three of the 10 highest ranked

stressors were time-related. The patient-related

stressors group had the highest mean (± standard

deviation [SD]) score (3.4 ± 0.8), followed by the

time-related stressors group (3.1 ± 0.8), staff-related

or technically related stressors group (2.6 ± 0.6),

income-related stressors group (2.5 ± 0.7), and job-related

stressors group (2.5 ± 0.7). Female dentists

had a higher mean score than male dentists for

patient-related, job-related, and staff-/technically

related stressors (3.5 vs 3.3, 2.6 vs 2.4, and 2.7 vs 2.5,

respectively; all P<0.05). Dentists with more than

20 years of practice (3.3), who held postgraduate

qualifications (3.2), or who had completed specialist

training (3.0) had a lower mean score for patient-related

stressors than those with less than 20 years

of practice (3.4, 3.5, and 3.4 respectively; all P<0.05).

Figure 1. Top 10 stressors ranked according to the percentage distributions of the respondents’ rating ‘4’ or ‘5’

Stress-coping strategies

The highest ranked strategy (with ratings ‘4’ or ‘5’)

to cope with occupational stress was ‘try to control

one’s own working situation / condition’ (59.0%),

followed by ‘pursue outside interests’ (58.6%), ‘avoid

the stressful situation’ (51.7%), and ‘take exercise’

(51.0%). Other less-commonly used strategies (<50%)

were ‘re-interpret problem positively’, ‘seek support

and advice’, ‘social gathering’, ‘devote yourself more

to your work’, ‘take medication’, and ‘others’.

Effects of occupational stress on work

The highest ranked effect (with ratings ‘3’ or ‘4’) of

occupational stress on work was to ‘cut down on

the amount of extra work or overtime’ (41.7%) and

‘take more frequent / longer breaks’ (30.7%). Fewer

than 30% of respondents reported ‘less satisfaction

with your job’, ‘work more slowly’, and ‘less able

to concentrate on your work’ as the effects of

occupational stress on work.

Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services

Survey and level of burnout

The mean (± SD) score for EE, DP and PA and the

level of burnout are shown in Figure 2. Approximately

a quarter of the respondents had a high EE level

(25.4%; 95% CI, 20.5%-30.3%) while 17.2% (95% CI,

12.9%-21.5%) and 39.0% (95% CI, 33.5%-44.5%) had

high DP and low PA level, respectively. Nonetheless

only 7.0% (95% CI, 4.1%-9.9%) of respondents had

a high level of overall burnout (ie high EE, high DP,

and low PA).

Figure 2. Level of burnout (low PA indicates high level of burnout)

Only 7.0% had a high level of overall burnout (high EE, high DP, and lower PA)

Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human

Services Survey, occupational stress, and

demographic variables

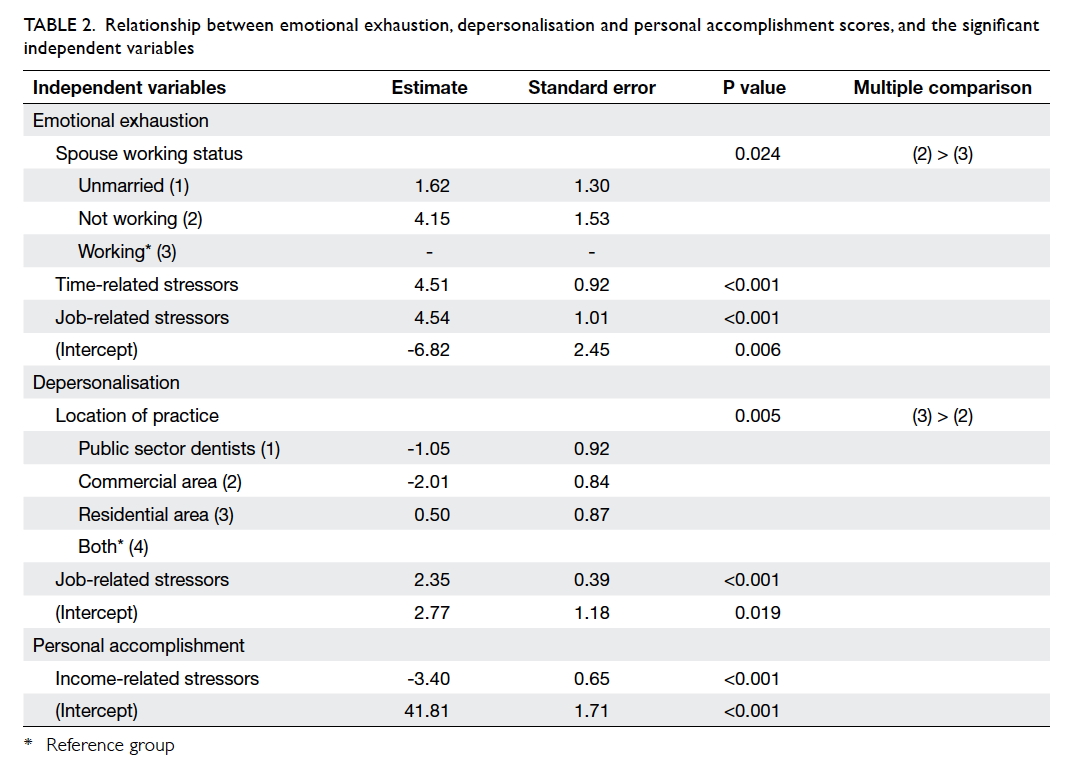

The relationship between EE, DP and PA scores, five

stressor groups, and the 12 demographic variables

was analysed by ANCOVA. The final models are

shown in Table 2. For EE, among the 17 independent

variables investigated, only three significant

variables (P<0.05) were selected in the final model.

The dentists whose spouses were not working had a

higher mean EE score by 4.15 compared with those

whose spouses were working (P=0.024). Those with

higher scores in the time-related stressors group

had higher EE scores. For every one unit increase

in time-related stressors group score, the mean EE

score increased by 4.51 (P<0.001). Finally, those with

higher scores in the job-related stressors group also

had higher EE scores; for every one unit increase

in job-related stressors group score, the mean EE

score increased by 4.54 (P<0.001). For DP, only

two significant variables (P<0.05) were selected

in the final model. Private dentists who worked in

residential areas had higher mean DP scores by 2.51

compared with those private dentists who worked

in commercial areas (P=0.005). Also, those with

higher scores in the job-related stressors group also

had higher DP scores; for every one unit increase

in job-related stressors group score, the mean DP

score increased by 2.35 (P<0.001). For PA, only one

significant variable (P<0.05) was selected in the final

model. Those with higher scores in income-related

stressors group were found to have lower PA scores.

For every one unit increase in job-related stressors

group score, the mean PA score decreased by 3.40

(P<0.001).

Table 2. Relationship between emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment scores, and the significant independent variables

Level of burnout, occupational stress, and

demographic variables

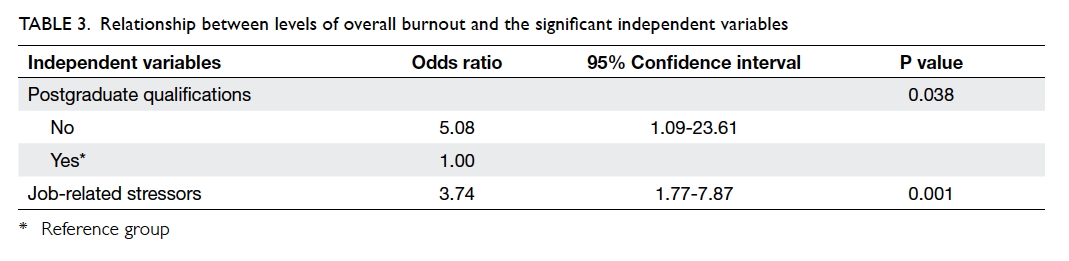

The relationships between levels of overall burnout

(high and low), five stressors groups, and the

demographic variables were analysed by multiple

logistic regression. The results are shown in Table 3;

only two significant variables (P<0.05) were selected.

The chance of having a high level of overall burnout

among dentists with no postgraduate qualifications

was 5.08 times higher (95% CI, 1.09-23.61) than those with postgraduate qualifications (P=0.038).

Also, for every one unit increase in job-related

stressors group score, the odds of having a high level

of overall burnout was 3.74 times as likely (95% CI,

1.77-7.87; P=0.001).

Discussion

This survey revealed that the highest ranked

stressors were patient-related. Several stress-coping

strategies and effects of occupational stress on work

were identified. Only 7% of dentists had a high level

of overall burnout. Dentists without postgraduate

qualifications and higher job-related stressor scores

were more likely to have a high level of overall

burnout.

Occupational stress and coping strategies

Comparison of these results with those of a previous

study published in 200116 reveals that the situation

in Hong Kong has changed little over 15 years. In

both surveys, six of the top 10 stressors were patient-related,

three were time-related, and one was income-related.

There was, however, an increase in the

percentage distributions of the stressors, indicating

an increased stress level for dentists in Hong Kong

in the past decade. This may be related to increasing

demands and expectations of patients. Patients can

now find much information on the internet and ask

many questions based on the information they may

find. This is a novel challenge for dentists. Moreover,

the property rents in Hong Kong have increased

much over the last 10 years with a consequent

increase in the overhead costs of running a dental

clinic. As a result, dentists need to work harder and

see more patients to generate sufficient income to

cover their costs.

Female dentists had higher mean scores than

male dentists for patient-related, job-related, and

staff-/technically related stressors. This may be

because they are taking care of their own family

as well as working as a dentist. Dentists with more

experience, higher postgraduate qualifications, and

specialist training had lower mean scores in the

patient-related stressors group. This may imply that

dentists with more competent skills and knowledge

were less stressed.

In the current and 200116 studies, the most

prevalent method of coping with stress was ‘try to

control one’s own working situation / condition.

Most dentists worked on their own and were self-reliant,

even when they were facing stress.

Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services

Survey and level of burnout

Higher EE score was significantly associated with

those dentists whose spouses were not working and

those with higher mean scores in time-related and

job-related stressors groups. The financial pressure

on a dentist may be lessened if the spouse works and

this may have contributed to the lower EE score.

Higher DP score was significantly associated with

working in a residential area and higher mean score

in job-related stressors group. This may be due to

differing patient profiles in residential areas. Those

who seek dental care from dentists in residential areas

may be less educated, and less willing or less able to

pay for dental treatment. Thus, the dentists have to

spend more time with each patient but accrue less

income with a consequent higher DP score. Lower

PA score was significantly associated with those

dentists with lower mean score in income-related

stressors group. One of the rewards for a dentist is

to earn a living by providing a professional dental

service. If a dentist has difficulty in earning, he may

have a lower sense of PA.

A high level of overall burnout was significantly

associated with a higher mean score in job-related

stressors group and no postgraduate qualifications.

Those with postgraduate qualifications may have

better knowledge, technique, and communication

skills to deal with patients. This may have contributed

to lower overall burnout.

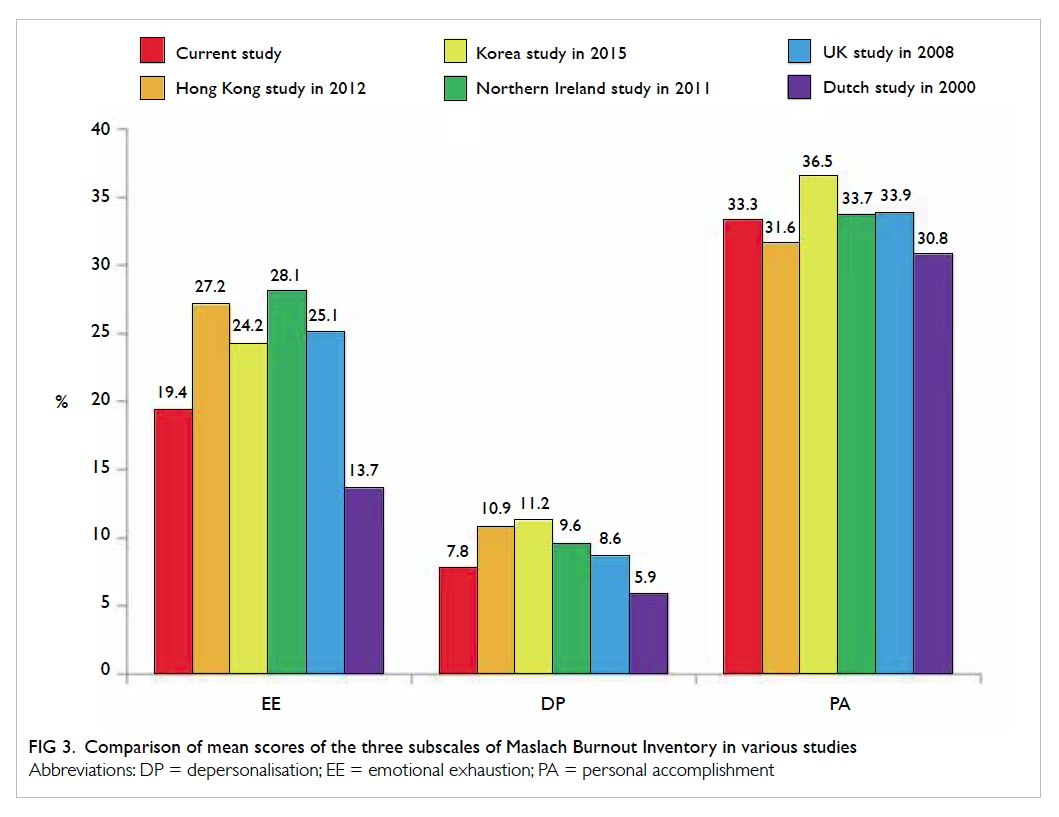

The mean scores of the three subscales (EE,

DP, and PA) of MBI of studies in Korea,8 Northern

Ireland,9 UK,10 Dutch,21 and Hong Kong doctors11

are shown in Figure 3 for comparison. Generally

speaking, the mean scores of EE and DP of dentists

in Hong Kong were lower than those in other

countries while mean PA score was in between. It is

possible that Hong Kong dentists can tolerate stress

better. In Hong Kong, the competition to study

dentistry is very strong. A secondary school student

must perform very well in public examinations to be

admitted to the only dental school in Hong Kong.

Locally trained students are used to this kind of keen

competition. In Hong Kong, lower mean EE and DP

scores and higher mean PA scores among dentists

suggest that they are not as stressful as medical

doctors. This may be due to the different nature of

their jobs. Most dentists in Hong Kong practise in

the private sector and seldom need to be on-call.

In comparison, a lot of Hong Kong medical doctors

work in public hospitals and need to be on-call.

Moreover, the public have high expectations of the

public health care service and this may contribute

to the higher level of burnout among Hong Kong

doctors.

Figure 3. Comparison of mean scores of the three subscales of Maslach Burnout Inventory in various studies

The level of burnout of the current study was

compared with that reported in Korea8 and the UK.10

The percentage distribution of high EE (Hong Kong

25.4%, Korea 41.2%, and UK 42.2%) and DP (Hong

Kong 17.2%, Korea 55.9%, and UK 19.5%) level of

Hong Kong dentists was lower compared with that

of Korean and UK dentists. Hong Kong dentists,

however, felt a lower sense of PA as reflected by the

higher percentage of low PA (Hong Kong 39.0%,

Korea 31.5%, and UK 31.9%). This suggests that the

dentists in Hong Kong had lower job satisfaction.

Although the level of overall burnout of Hong Kong

dentists was less than that in other countries, this

issue should not be overlooked. Dentistry is quite a

lonely profession that requires an individual to work

alone most of the time. Peer support and sharing is

important for the development of dentistry in Hong

Kong.

Limitations of the study

The response rate of the current study was low

(<30%) although it was similar to other studies of

health care professionals in Hong Kong. The selected

dentists might be very busy and might not have time to

complete the questionnaires. Others might not have

been interested. Those dentists with a high level of

burnout might have felt the questions too sensitive

and thus been unwilling to participate. For those

who participated, as stress and burnout were self-reported,

there might have been information bias

because of social desirability and thus our results might

underestimate the level of stress and burnout among

dentists in Hong Kong. As in all cross-sectional

surveys, a causal relationship could not be established.

With the small sample size, there was a possible lack of

statistical power for the multiple logistic regression

as evidenced by the wide 95% CI of the odds ratio. In

order to increase the response rate of future surveys,

we may consider phoning each selected dentist to

check if they have received the questionnaires and

to invite them to participate. We may also consider

using the internet for data collection.

Recommendation

Dentists with a higher stress level may consider

working less to relieve pressure: approximately one

quarter of dentists worked more than 50 hours a

week, which contributed to the time-related stress.

Dentists are advised to update their knowledge and

skills to equip them for the increasing expectations

and challenges from patients and society.

Conclusion

Patient-related stressors are the top occupational

stressors experienced by dentists in Hong Kong.

Nonetheless a small proportion of dentists have high

overall burnout. There was a positive association

between occupational stress and level of burnout.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of the Faculty of

Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong for their

assistance in this study. We would also like to thank

all the dentists who participated in the survey.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gorter RC, Albrecht G, Hoogstraten J, Eijkman MA. Work

place characteristics, work stress and burnout among

Dutch dentists. Eur J Oral Sci 1998;106:999-1005. Crossref

2. Rada RE, Johnson-Leong C. Stress, burnout, anxiety and

depression among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:788-94. Crossref

3. US National Library of Medicine. Depression: what is

burnout? Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072470/. Accessed 15 Mar 2017.

4. Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory

manual. Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists

Press; 1981.

5. Maslach C. Burned-out. Can J Psychiatr Nurs 1979;20:5-9.

6. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced

burnout. J Organ Behav 1981;2:99-113. Crossref

7. Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory manual.

2nd ed. Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists

Press; 1986.

8. Jin MU, Jeong SH, Kim EK, Choi YH, Song KB. Burnout

and its related factors in Korean dentists. Int Dent J

2015;65:22-31. Crossref

9. Gorter RC, Freeman R. Burnout and engagement in

relation with job demands and resources among dental

staff in Northern Ireland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol

2011;39:87-95. Crossref

10. Denton DA, Newton JT, Bower EJ. Occupational burnout

and work engagement: a national survey of dentists in the

United Kingdom. Br Dent J 2008;205:E13;discussion 382-3.

11. Siu C, Yuen SK, Cheung A. Burnout among public doctors

in Hong Kong: cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Med J

2012;18:186-92.

12. Doolittle BR, Windish DM. Correlation of burnout

syndrome with specific coping strategies, behaviors, and

spiritual attitudes among interns at Yale University, New

Haven, USA. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2015;12:41. Crossref

13. Jin WM, Zhang Y, Wang XP. Job burnout and organizational

justice among medical interns in Shanghai, People’s

Republic of China. Adv Med Educ Pract 2015;6:539-44.

14. Portero de la Cruz S, Vaquero Abellán M. Professional

burnout, stress and job satisfaction of nursing staff at a

university hospital. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2015;23:543-52. Crossref

15. Singh C, Cross W, Jackson D. Staff burnout—a comparative

study of metropolitan and rural mental health nurses

within Australia. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2015;36:528-37. Crossref

16. Wong MC, Ng KK, Tang AK, Tang GC, Lam VN.

Occupational stress among dental practitioners in Hong

Kong. Hong Kong Dent Assoc Millennium Rep 2001;II:50-5.

17. The Dental Council of Hong Kong. List of registered

dentists under the General Register. Available from: http://www.dchk.org.hk/en/list/index.htm. Accessed 22 Oct

2015.

18. Cooper CL, Watts J, Kelly M. Job satisfaction, mental health,

and job stressors among general dental practitioners in the

UK. Br Dent J 1987;162:77-81. Crossref

19. Waddington TJ. New stressors for GDPs in the past 10

years. Br Dent J 1997;182:82-3. Crossref

20. Kopec JA, Esdaile JM. Occupational role performance in

persons with back pain. Disabil Rehabil 1998;20:373-9. Crossref

21. Gorter RC, Eijkman MA, Hoogstraten J. Burnout and

health among Dutch dentists. Eur J Oral Sci 2000;108:261-7. Crossref