Predictive factors for length of hospital stay following primary total knee replacement in a total joint replacement centre in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2017 Oct;23(5):435–40 | Epub 4 Aug 2017

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj166113

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Predictive factors for length of hospital stay following primary total knee replacement in a total joint replacement centre in Hong Kong

CK Lo, MB, BS; QJ Lee, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); YC Wong, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Joint Replacement Centre, Yan Chai Hospital, Tsuen Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CK Lo (lpluswck@live.com)

Abstract

Introduction: The demand for total knee

replacement in Hong Kong places tremendous

economic burden on our health care system.

Shortening hospital stay reduces the associated cost.

The aim of this study was to identify perioperative

predictors of length of hospital stay following

primary total knee replacement performed at a high-volume

centre in Hong Kong.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed all primary

total knee replacements performed at Yan Chai

Hospital Total Joint Replacement Centre from

October 2011 to October 2015. Perioperative factors

that might influence length of stay were recorded.

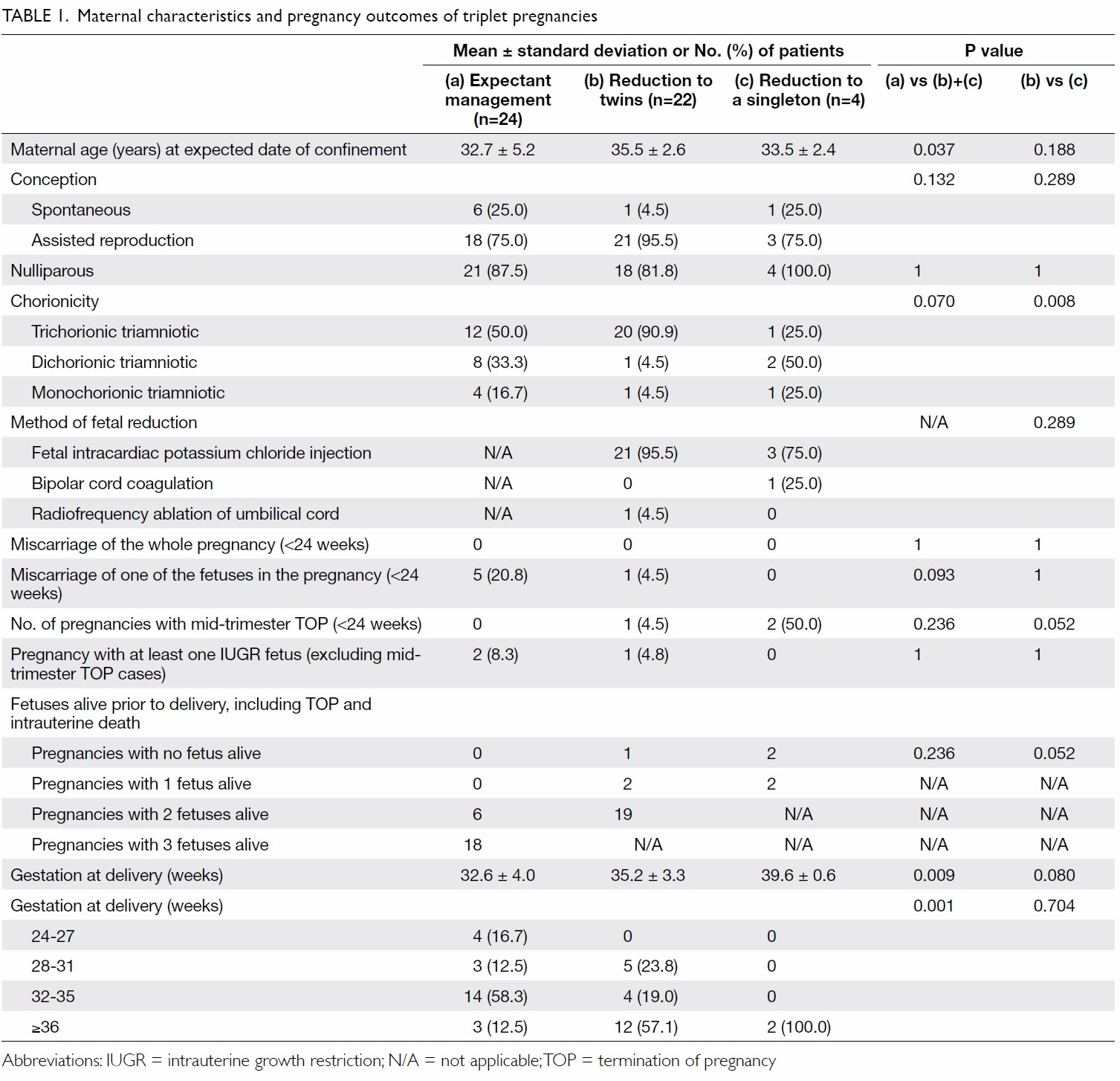

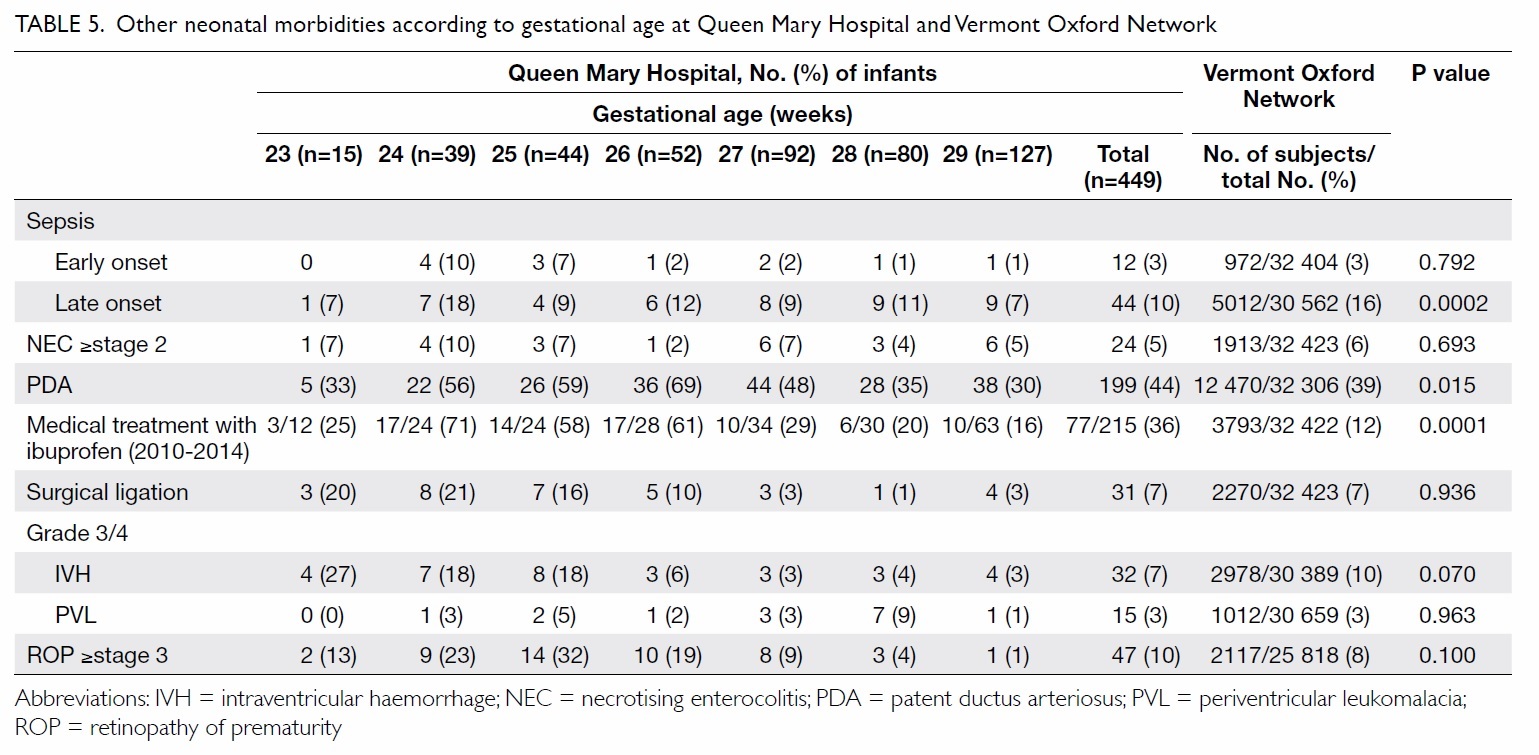

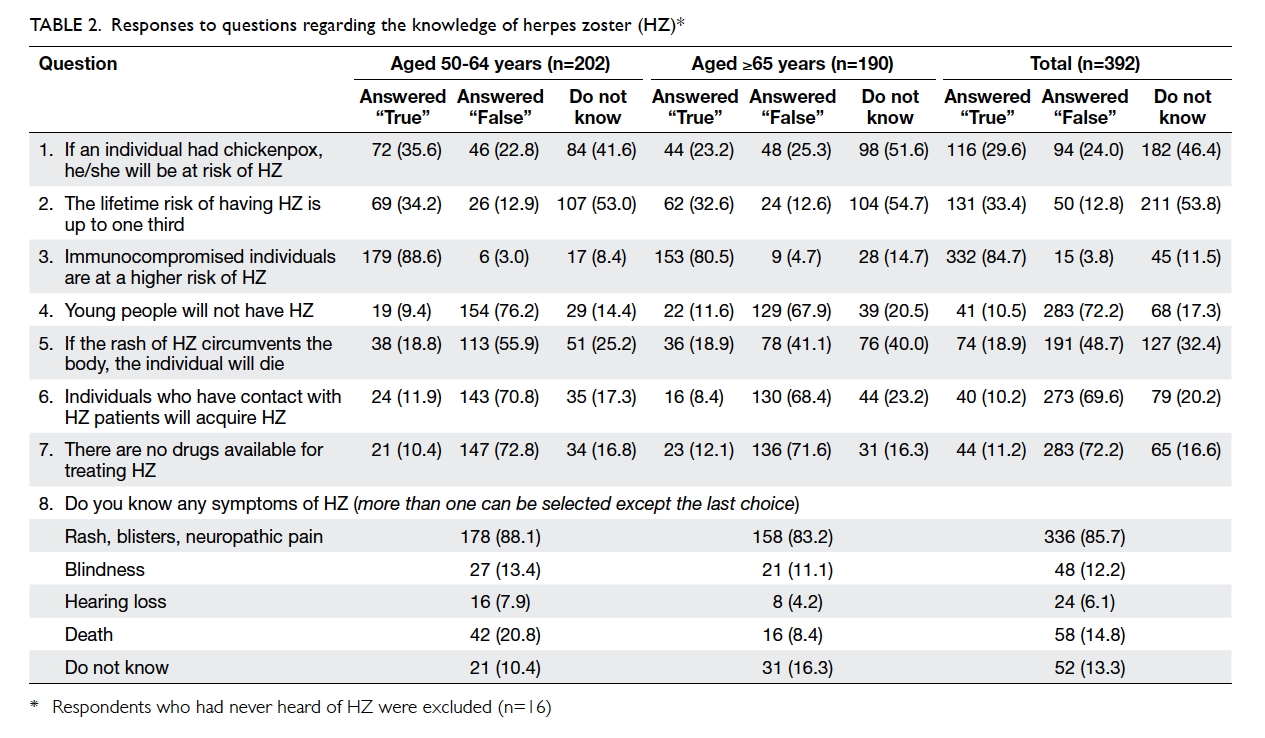

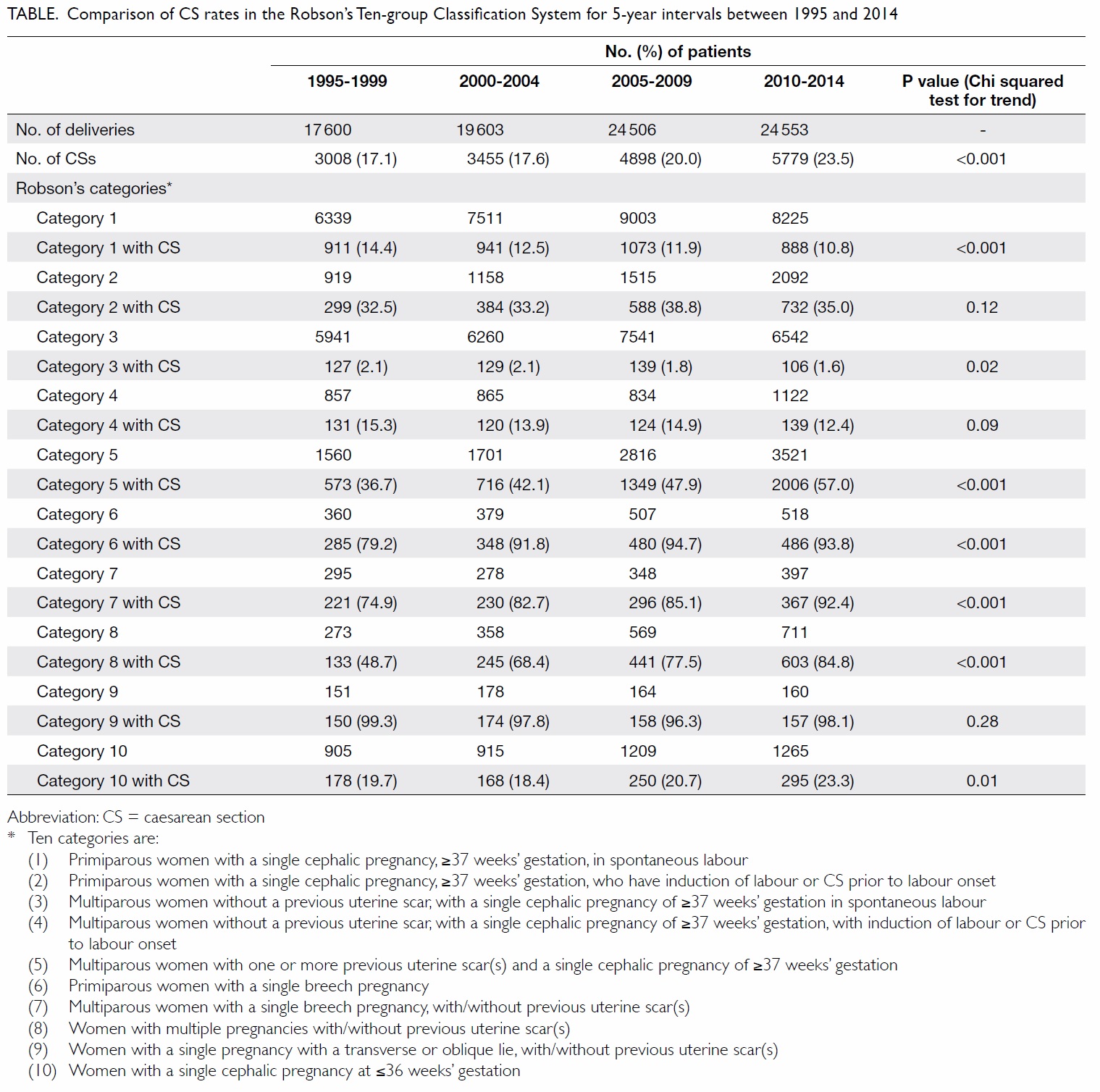

Results: A total of 1622 patients were identified. The

mean length of hospital stay was 6.8 days. Predictors

of prolonged hospital stay following primary total

knee replacement were advanced age; American

Society of Anesthesiologists physical status class

3; bilateral total knee replacement; in-patient complications; and the need for blood transfusion,

postoperative intensive care unit admission, and

urinary catheterisation.

Conclusions: Evaluating factors that can predict

length of hospital stay is the starting point to improve

our current practice in joint replacement surgery.

Prediction of high-risk patients who will require a

longer hospitalisation enables proactive discharge

planning.

New knowledge added by this study

- Advanced age; American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status class 3; bilateral operation; in-patient complications; and the need for blood transfusion, postoperative intensive care unit admission, and urinary catheterisation were predictors for length of hospital stay after primary total knee replacement.

- Prediction of high-risk patients who will require longer hospitalisation based on perioperative factors enables proactive discharge planning.

- Establishment of a urinary catheterisation protocol might help to shorten hospital stay following primary total knee replacement.

Introduction

With a rising incidence of degenerative arthritis in

our ageing population, together with an increase in

popularity of joint replacement surgery, the demand

for total knee replacement (TKR) is expected to grow

in Hong Kong.1 This places a tremendous economic

burden on our health care system. The associated

cost of hospital stay can be reduced by shortening

the length of hospital stay (LOS). With more than 3000

TKRs performed in public hospitals in Hong Kong

each year,2 and given the cost per in-patient day of

HK$4000, shortening the LOS by 1 day could save

HK$12 million every year. Identification of factors

that extend hospital stay, which is a starting point for

reducing LOS, can reduce the financial burden on

the health care system.

The aim of this study was to identify

perioperative predictors of LOS following primary

TKR in a high-volume centre in Hong Kong.

Methods

All patients admitted for primary TKR from

October 2011 (when the Joint Replacement Centre

in Yan Chai Hospital in Hong Kong was established)

to October 2015 were included in the study. Data

of patients were collected retrospectively from

the Clinical Management System of the Hospital

Authority. The study was approved by the Kowloon

West Cluster Research Ethics Committee.

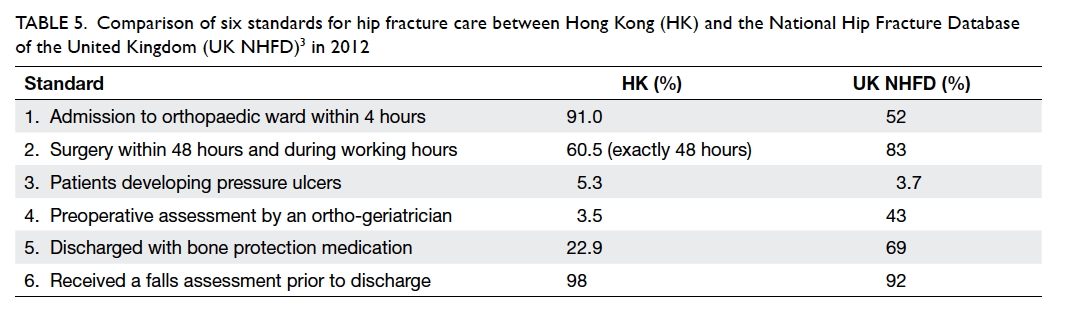

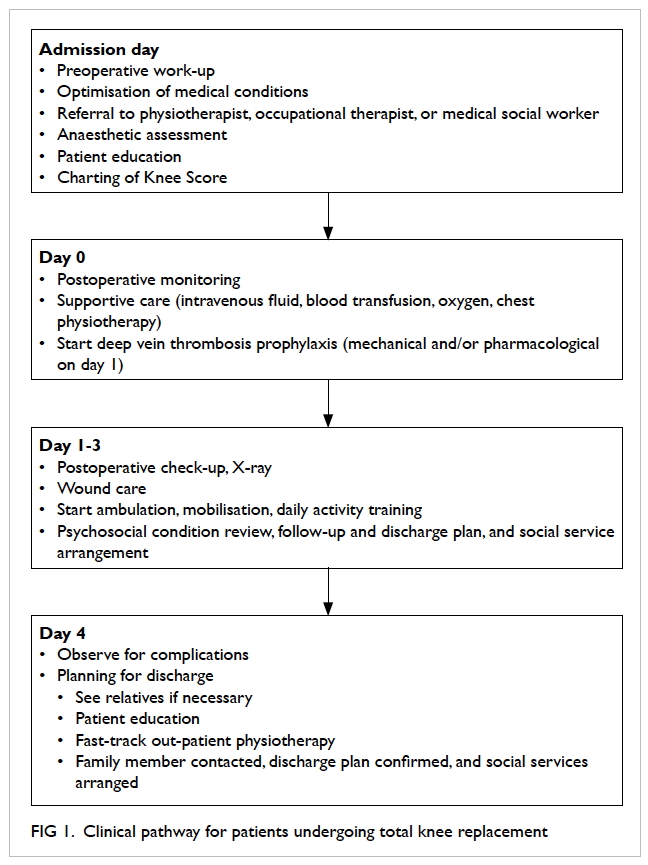

Patients who undergo TKR in our centre attend

a preadmission clinic 1 month before operation for their preoperative work-up and anaesthetic

assessment, and to be given information by surgeons

and a specialised nurse about the procedure,

rehabilitation, and benefits and complications of

TKR. Patients were admitted on the day of surgery

or earlier for medical optimisation or social reasons.

All operations were performed by or under the

supervision of a joint surgeon who adopted a

medial parapatellar approach and used a variety of

cemented implants. A tourniquet was applied and

the patella was routinely resurfaced. A standardised

clinical pathway of postoperative monitoring,

investigations, mobilisation, and anticoagulation

was applied in all patients (Fig 1). Physiotherapy

was commenced on the first postoperative day

and continued daily until discharge. Patients were

cleared for discharge when medically stable, walking

independently, and functionally able to return to

their home environment. Independent walking was

defined as walking stably without assistance from

another person with or without a walking aid.

The primary outcome measure of the study was

LOS, defined as the number of days in hospital from

the day of surgery to the day of discharge. The following

factors were analysed: age; gender; body mass index

(BMI); American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

physical status classification; type of operation

(unilateral versus bilateral TKR); preoperative

haemoglobin level; in-patient complications; and

requirement for postoperative transfusion, drain

insertion, postoperative intensive care unit (ICU)

care, and urinary catheterisation for postoperative

urinary retention. Because the ASA classification has

only been documented in the Clinical Management

System since August 2014, such information could

be retrieved for only 467 patients in this study.

The LOS ranged from 3 to 46 days. Since the

distribution was highly skewed, a non-parametric

approach was used in the analysis. A univariate

analysis for all the studied predictive factors was

first performed. Mann-Whitney test was used to

analyse categorical variables. These included gender,

BMI, ASA classification, type of operation, in-patient

complications, drain insertion, postoperative

ICU care, and urinary catheterisation. Spearman’s

rank correlation coefficient was used to analyse

continuous variables including age, preoperative

haemoglobin level, and blood transfusion. Following

univariate analysis, significant predictive factors

were subjected to multivariable linear regression

analysis to test the effect of each significant factor

after adjusting for the others. A P value of ≤0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

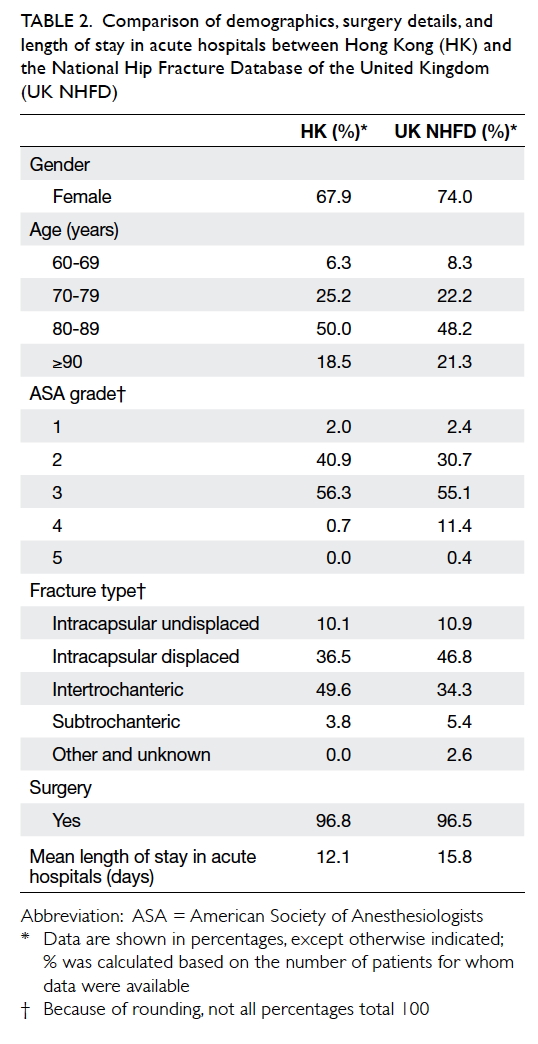

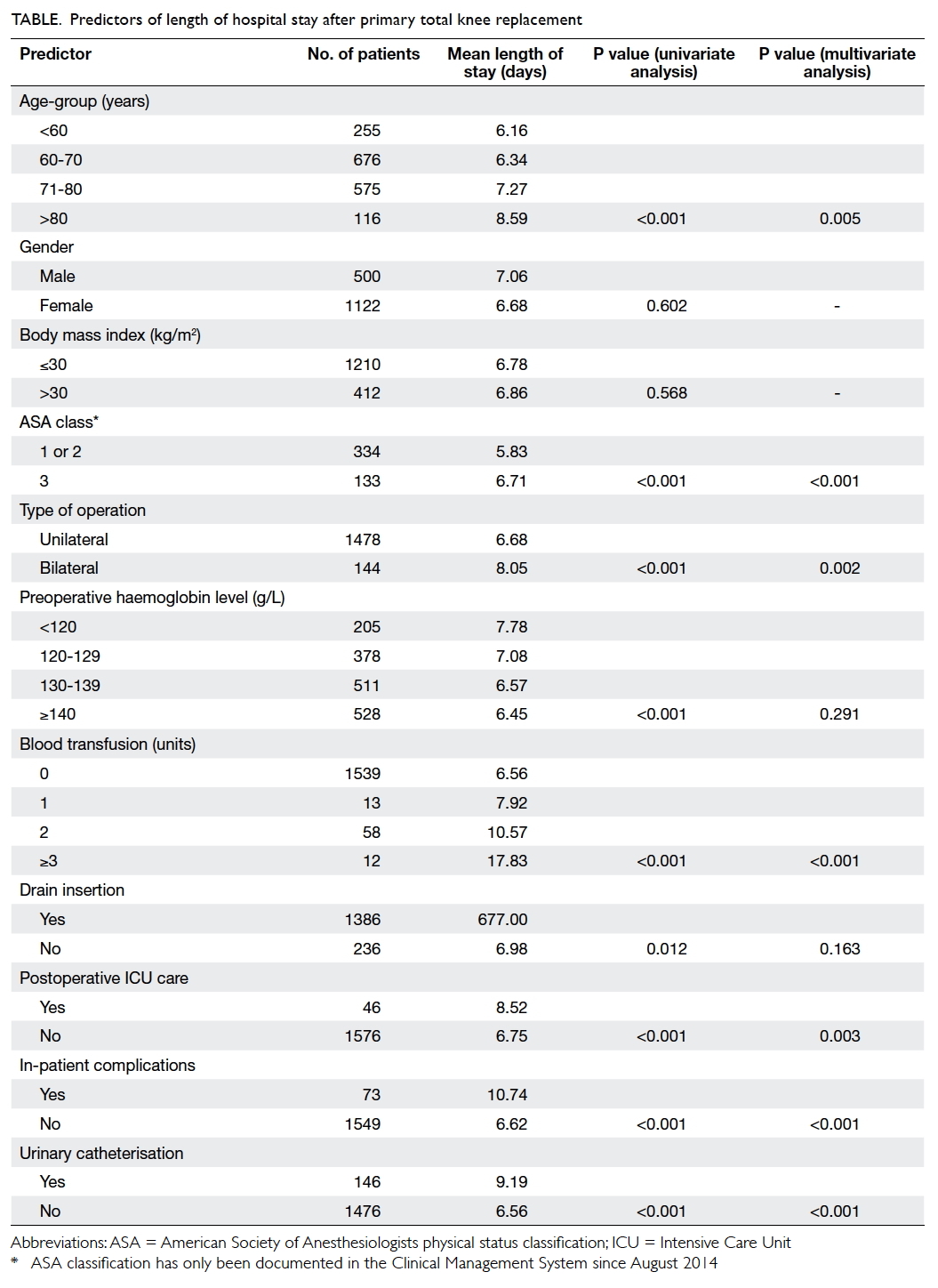

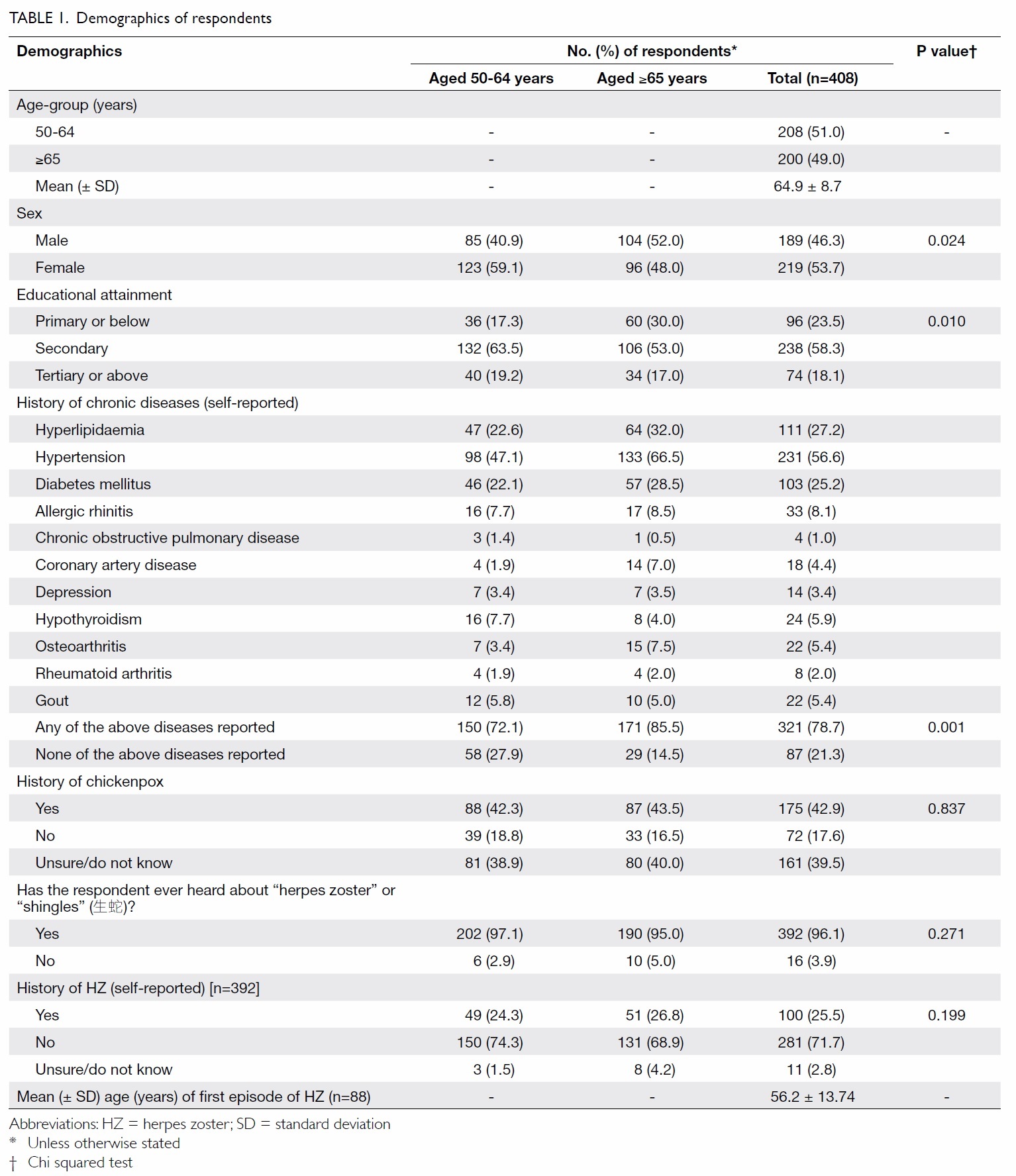

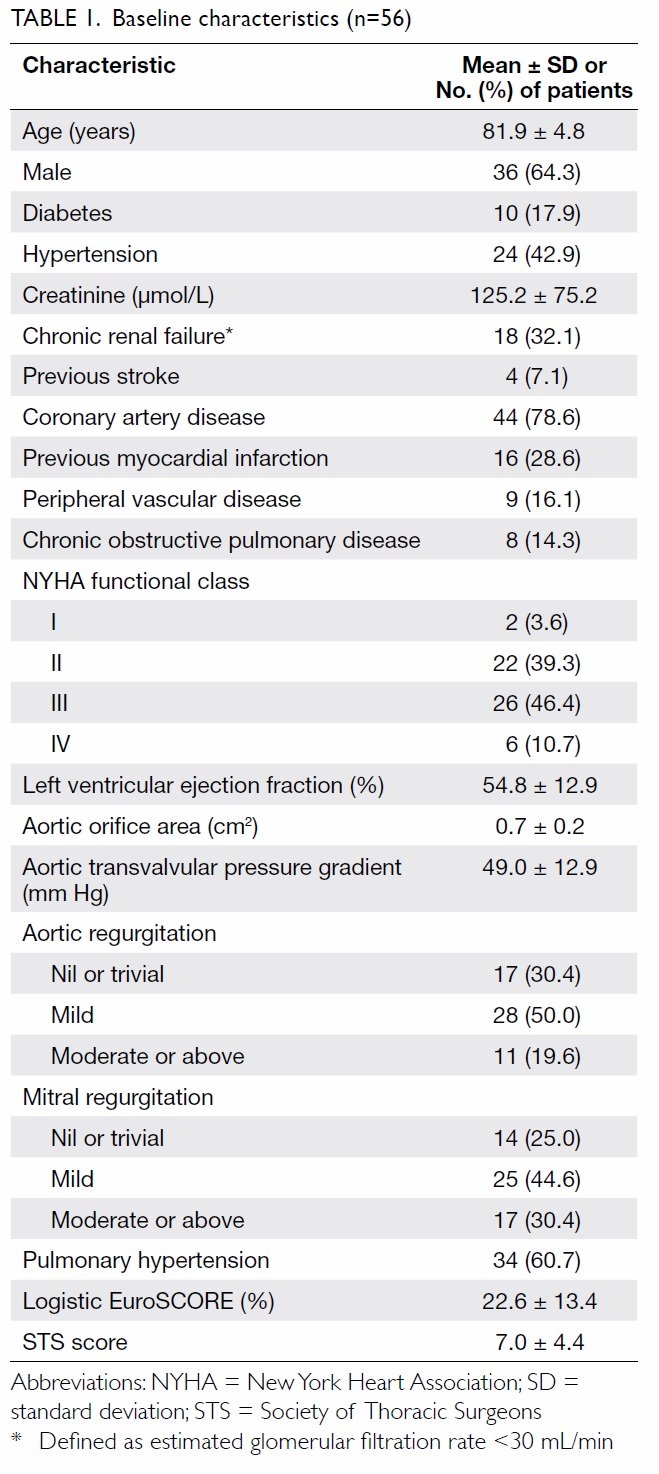

A total of 1622 patients were reviewed in this study.

Patients who received total hip replacement and

revision total knee replacement in our centre were excluded. The mean (range) and median LOS were

6.8 (3-46) days and 6 days, respectively. The Table

shows the categories for each predictive factor, the

number of patients in each category, the mean LOS for each category, and the P values for univariate and

multivariate analysis.

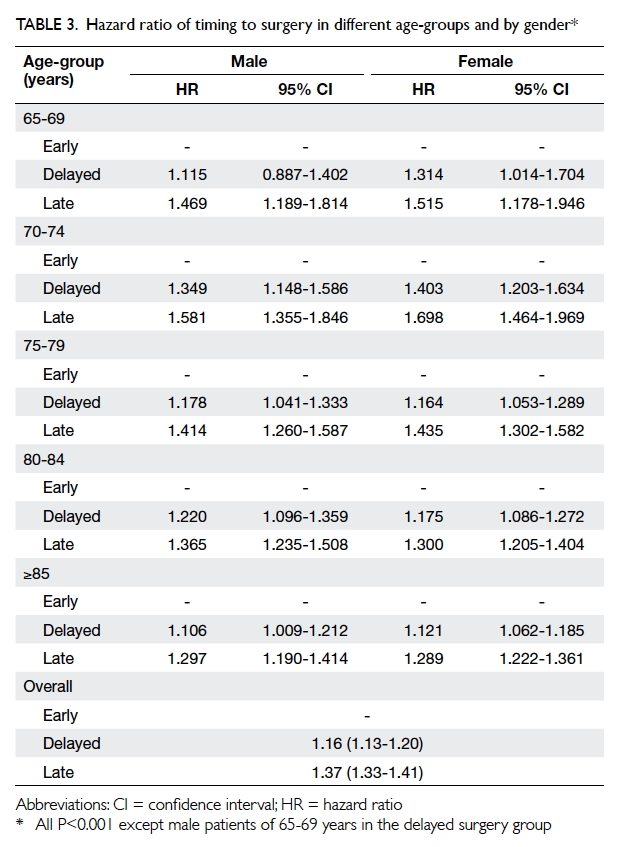

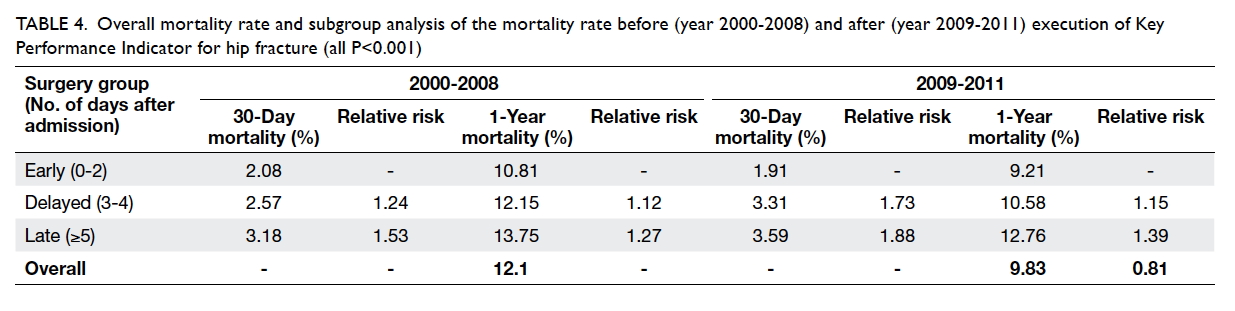

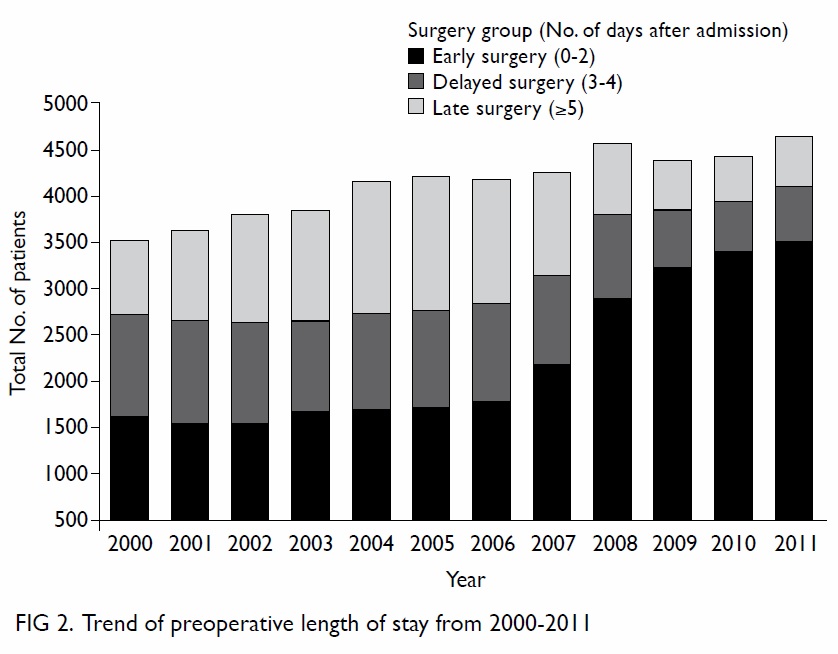

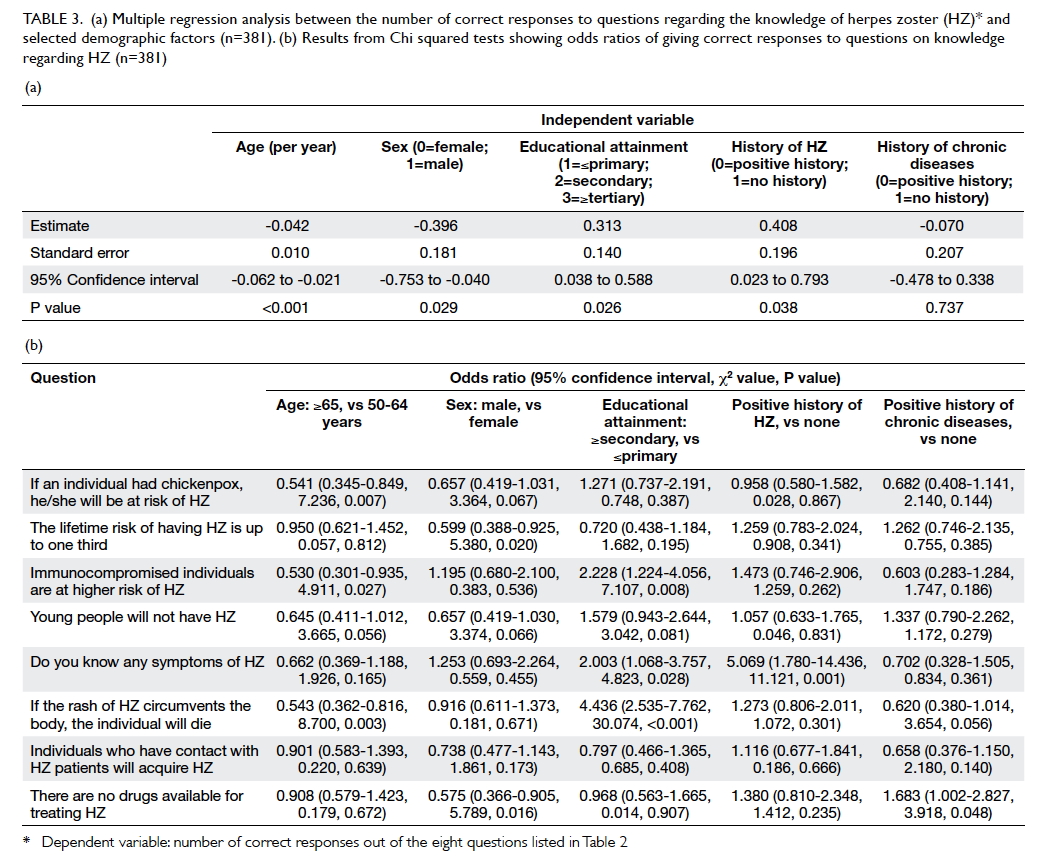

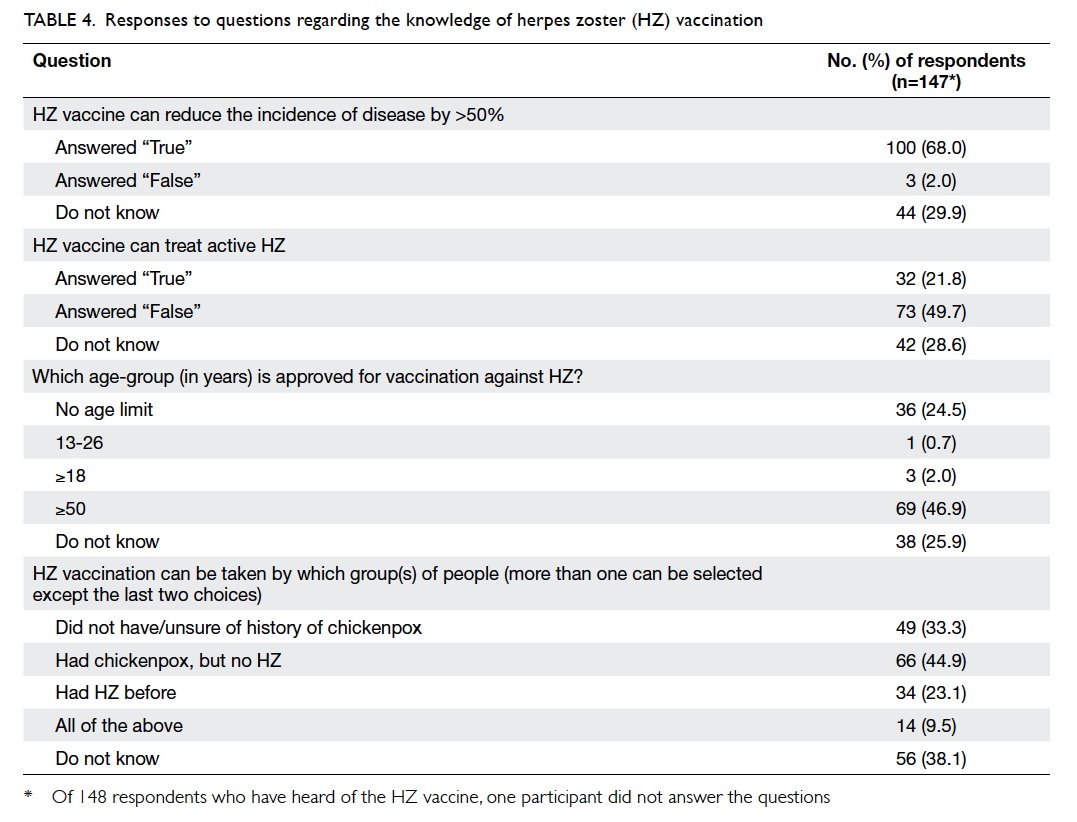

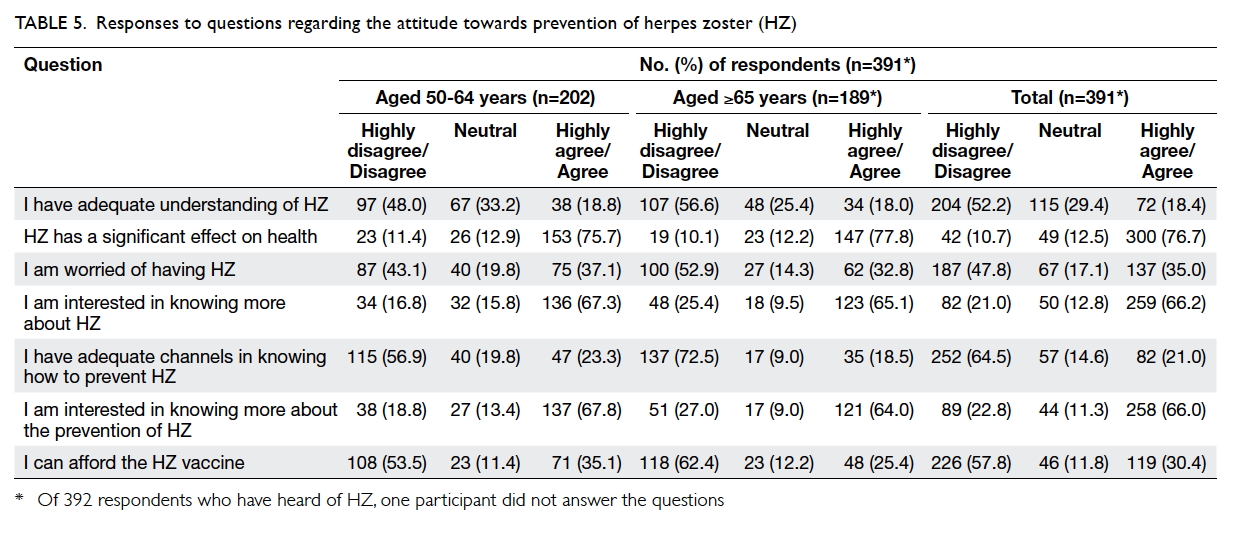

Age; ASA class; type of operation; preoperative

haemoglobin level; in-patient complications;

requirement for blood transfusion, drain insertion,

postoperative ICU care, and urinary catheterisation

were significant predictive factors in the univariate

analysis. When these significant factors were

adjusted for the effect of the other factors using

multiple linear regression, only advanced age; ASA

class 3; bilateral TKR; in-patient complications;

and the need for blood transfusion, postoperative

ICU care, and urinary catheterisation remained

significant.

Discussion

Several studies of LOS in a Caucasian population

have been published, but the study samples were

usually highly heterogeneous and included patients

with total hip as well as unicompartmental knee

replacement.3 4 This is the first study to exclusively

examine the LOS following TKR in a Chinese

population. We believe both cultural-specific patient

factors and the unique hospital setting in Hong Kong

significantly influence LOS. Identifying the predictive

factors in our own population is important to reduce

LOS and the associated cost. Factors that have been

shown in previous studies to have an influence

include age,5 gender,5 ASA class,6 type of surgery,7 requirement for blood transfusion,8 and in-patient

complications.8 9 Data for the influence of BMI7 8 10 and preoperative haemoglobin level3 8 11 are equivocal.

We also studied factors not previously examined

including the need for drain insertion, postoperative

ICU admission, and Foley catheterisation due to

urinary retention.

This study confirmed other previously

reported risk factors for longer LOS. Age and ASA

class were expected to be predictors of LOS and were

significant in many other studies.3 4 5 6 Classification of

ASA physical status is a measurement of the patient’s

co-morbidity and general fitness. Patients with

advanced age and decreased physical fitness will find

the required intensive rehabilitation difficult and

thus require a longer hospital stay.

The rehabilitation necessary after TKR is

demanding and can account for the longer LOS

required following bilateral TKR.7 Patients who

require bilateral TKR have sequential TKRs

performed in a single anaesthetic session. In our

study, the mean LOS is 1.37 days longer in such

patients. Most patients with degenerative arthritis

have disease affecting both knees. Patients who

undergo unilateral TKR commonly request TKR

for the other side due to significant improvement of

symptoms on the operated side. The combined LOS

for two admissions is obviously longer than that for a

single admission for bilateral TKR. Several previous

studies have demonstrated a comparable safety

profile between bilateral TKR and unilateral TKR in

properly selected patients.12 13 14 15 Patients with bilateral

osteoarthritis of the knee should be encouraged to undergo bilateral TKR provided they can tolerate the

procedure.

Blood management has always been a

contentious issue in TKR. Both preoperative

haemoglobin level and requirement for blood

transfusion were significant predictive factors for

LOS in our univariate analysis. Only requirement

for blood transfusion, however, remained significant

after multivariate analysis. This signifies that the

association between preoperative haemoglobin

level and LOS is due to the requirement for a blood

transfusion rather than the effect itself. It is well

documented that preoperative haemoglobin level is

the single most important predictor of need for blood

transfusion following TKR.16 This is why preoperative

haemoglobin level was a significant predictive factor

for LOS in some studies although it is not in our

study. Raut et al8 reported a significant association

between LOS and both preoperative haemoglobin

level and blood transfusion requirement although

multivariate analysis was not performed. Husted et

al3 reported both preoperative haemoglobin level and

blood transfusion to be significant predictive factors

for LOS, yet more than half of the patients recruited

in their study underwent total hip replacement (THR).

The intrinsic difference between THR and TKR

explains the difference between our and Husted et al’s findings.

Postoperative ICU care delayed rehabilitation

and inevitably prolonged LOS. This factor

remained significant after adjustment for ASA

classification. Most of our patients were admitted

to the ICU for postoperative monitoring of medical

co-morbidities. A commonly encountered reason

for ICU monitoring is obstructive sleep apnoea.17

Patients at risk of obstructive sleep apnoea should

be identified and referred to an ear, nose, and throat

surgeon for assessment and early management.18 The

need for ICU admission and prolonged LOS may

be eliminated if medical conditions are optimised

before TKR.

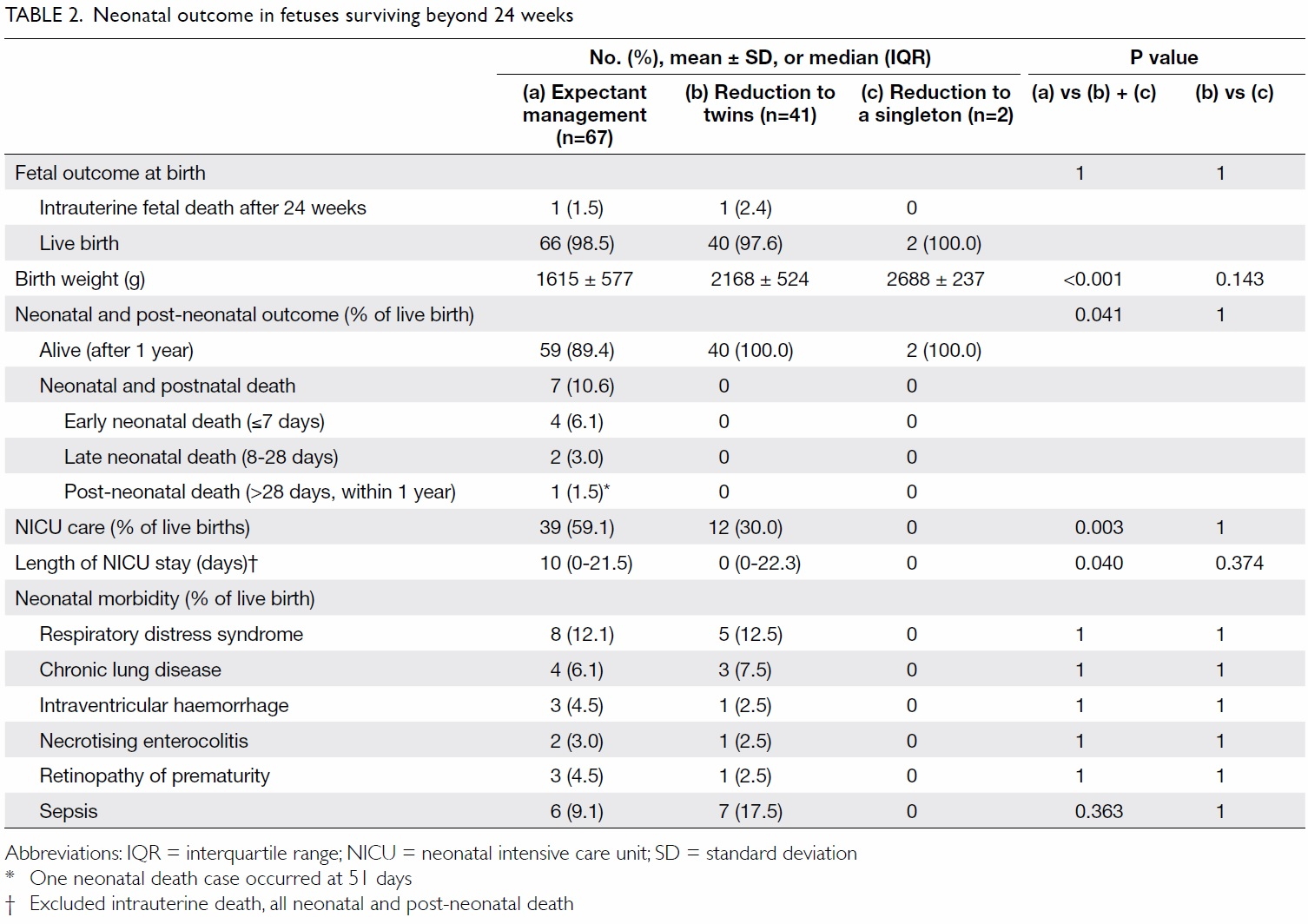

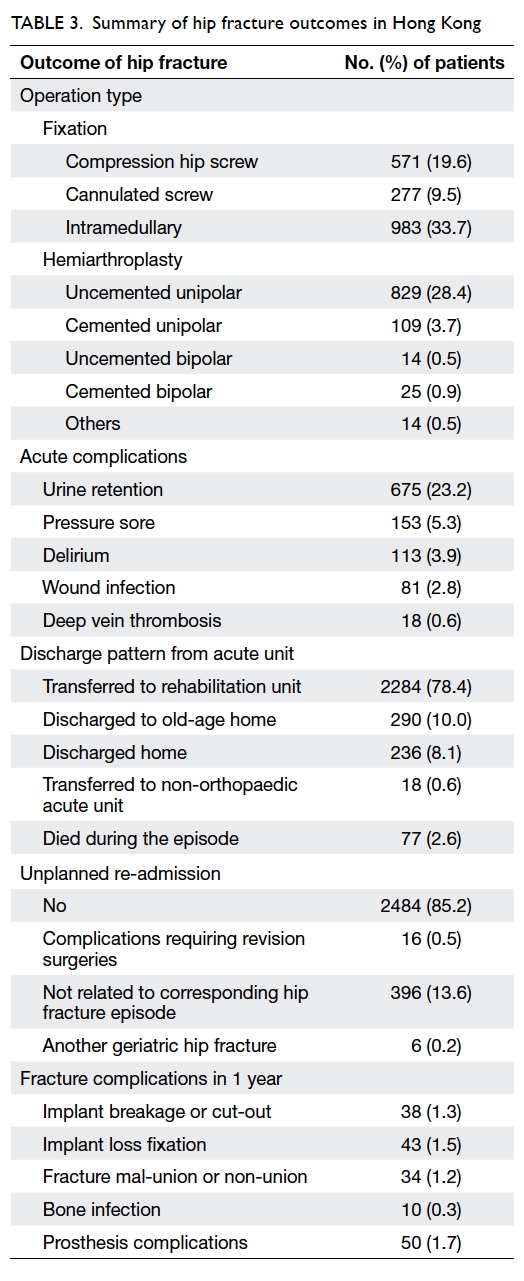

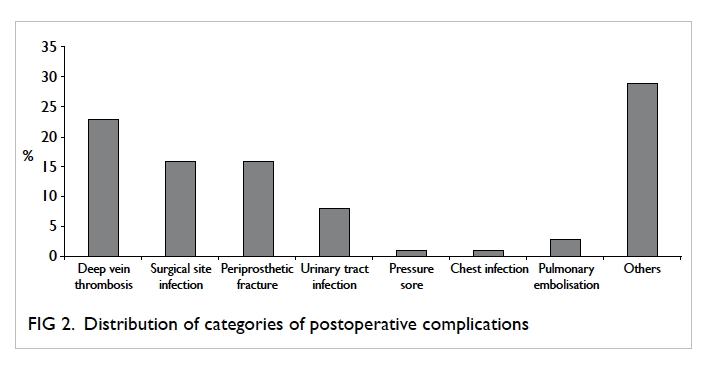

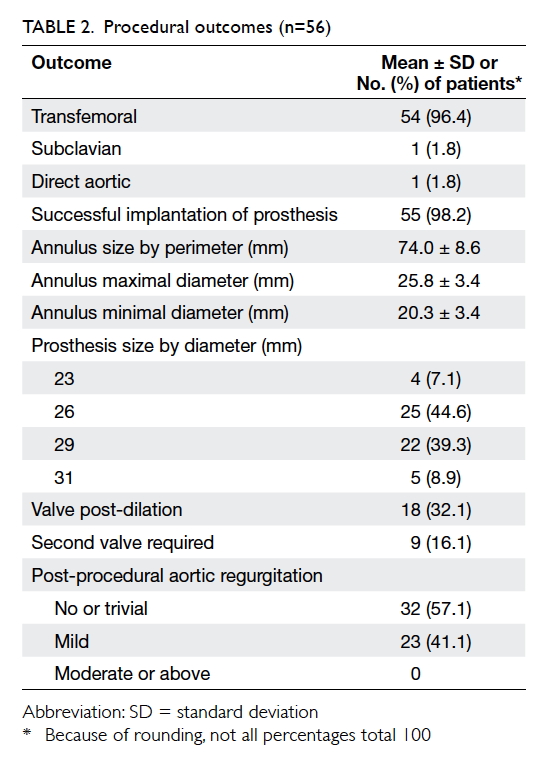

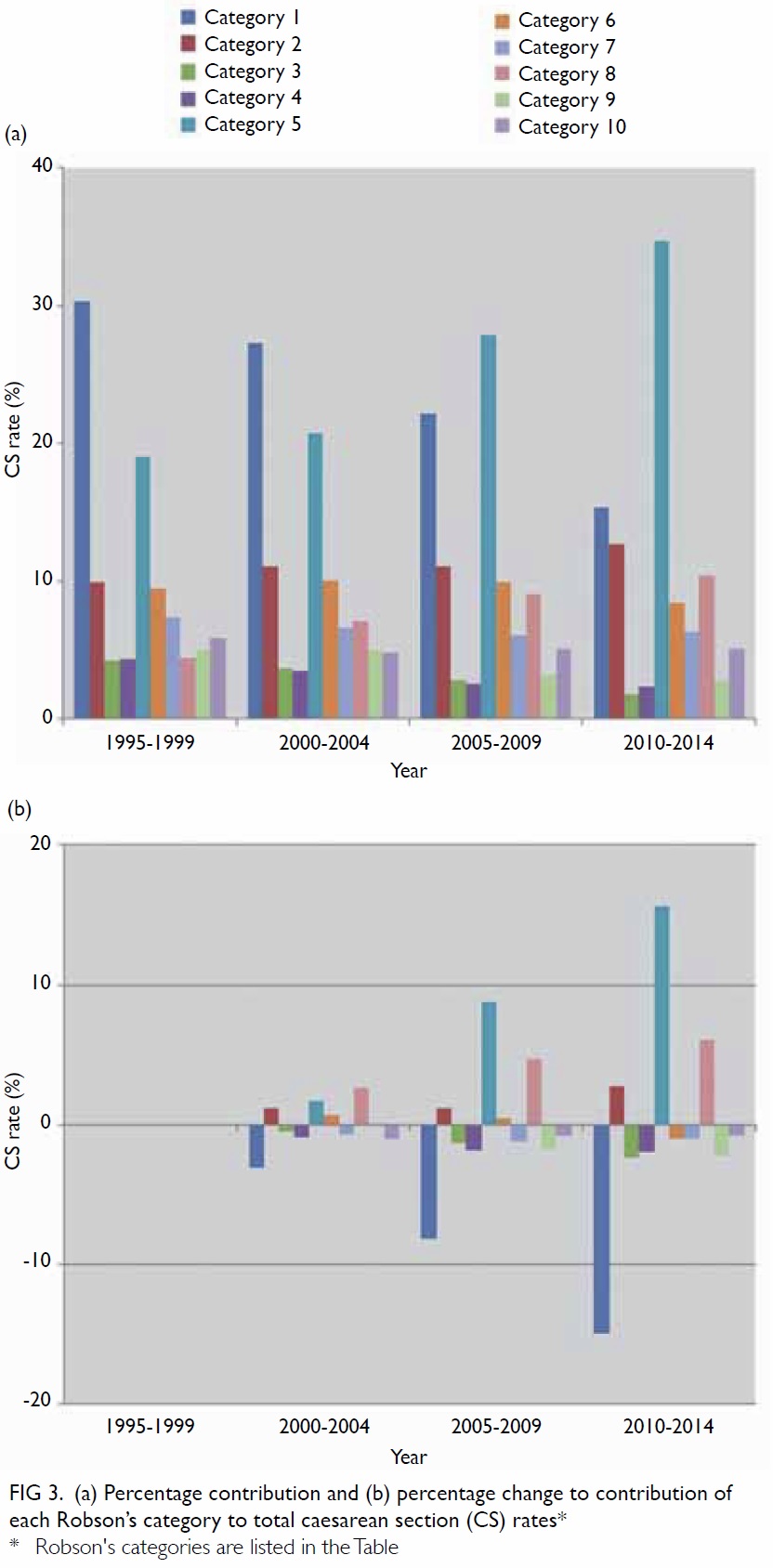

Patients who develop in-patient complications

were likely to stay longer in hospital; this is consistent

with the findings in the literature.8 9 Patients who

have complications require further work-up and

management, this increases utilisation of resources

and cost in addition to the increased LOS.9 Every

effort should be made to avoid complications. We

classified complications into seven groups based on

our experience. They included deep vein thrombosis,

surgical site infection, periprosthetic fracture,

urinary tract infection, pressure sore, chest infection,

and pulmonary embolism (Fig 2). Any complication

that did not fall into one of these categories was

documented as ‘others’. The top three complications

were deep vein thrombosis, surgical site infection,

and periprosthetic fracture; these altogether account

for 56% of all complications. Patients who developed

deep vein thrombosis required warfarinisation and dose titration prior to discharge. Patients who

developed a wound infection required intravenous

antibiotics, surgical debridement, and close

monitoring of the wound. Those with periprosthetic

fracture required protected weight-bearing that

complicated rehabilitation. We believe strict

adherence to anticoagulation guidelines, meticulous

wound care, and careful implant insertion are key

to avoid complications, prolonged LOS, and more

importantly, patient suffering.

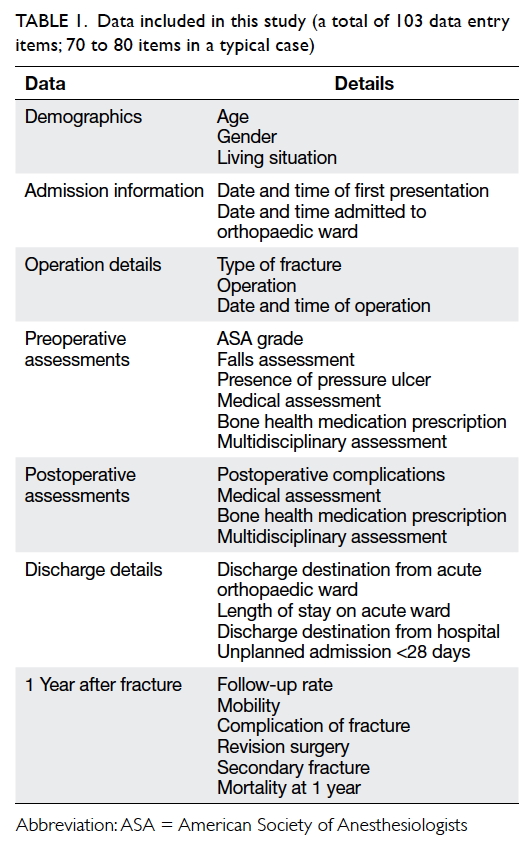

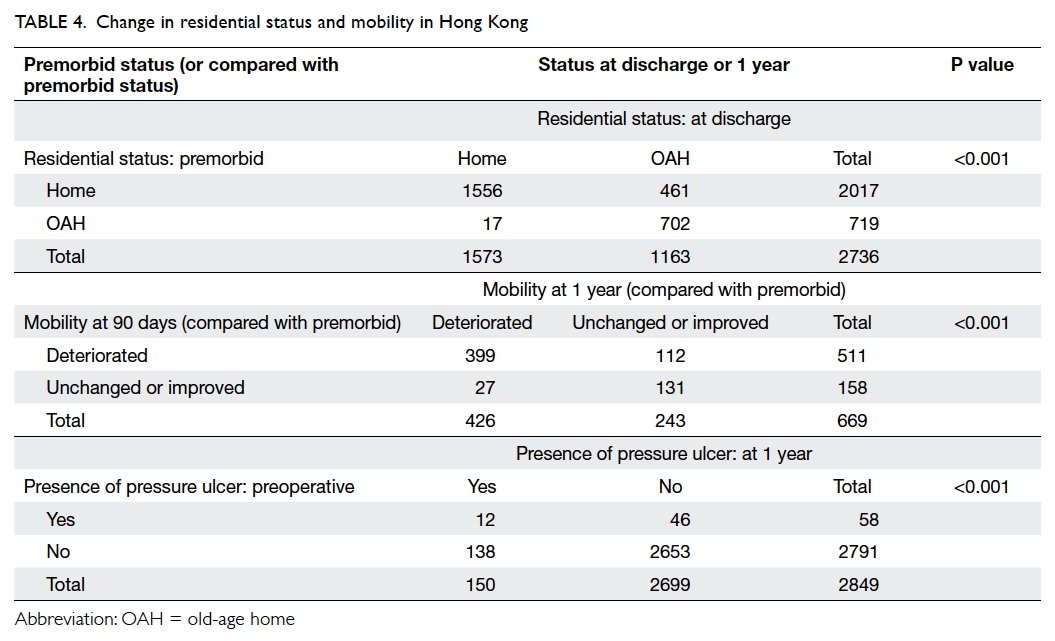

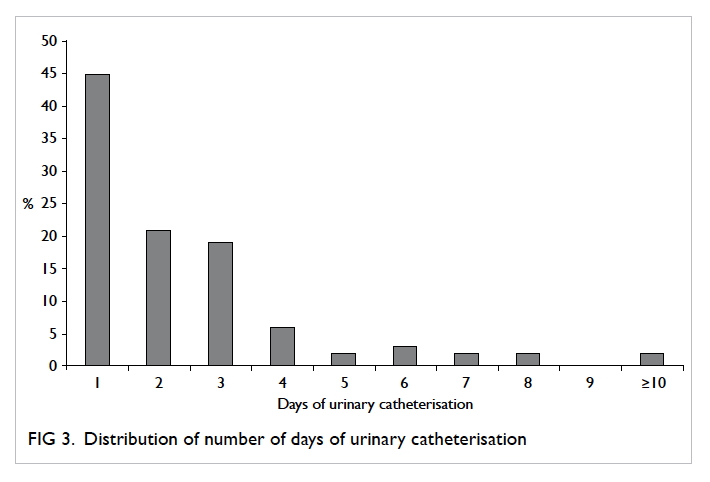

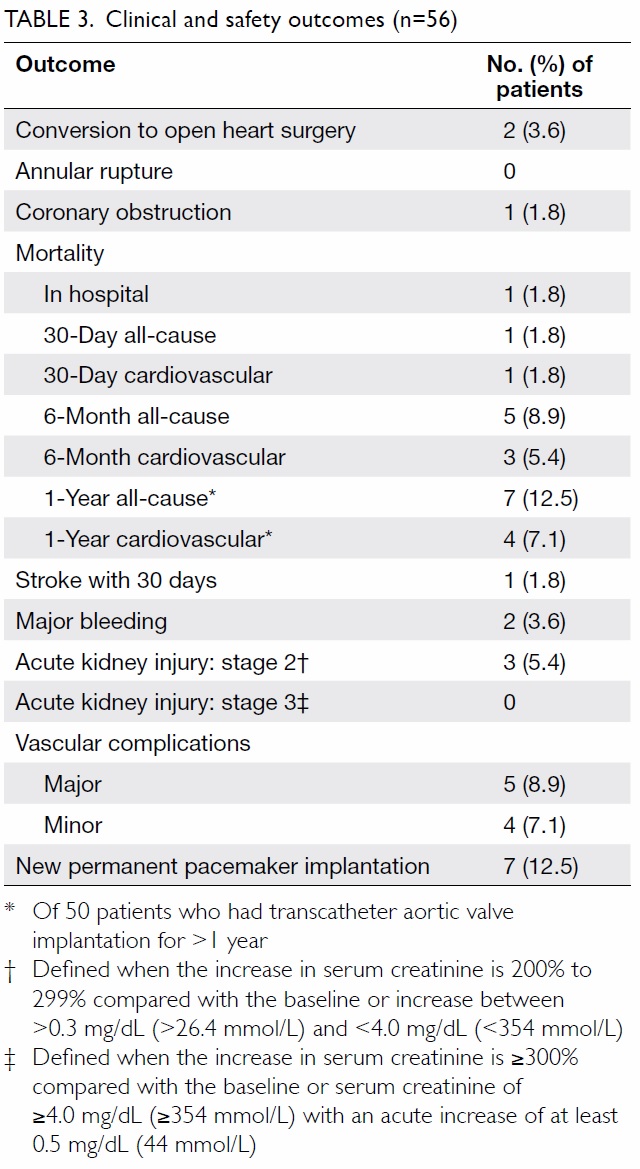

In our centre, a bladder scan is performed in

patients who do not pass urine for 8 hours following

TKR. Those with a urinary volume of ≥500 mL

undergo bladder drainage via a urinary catheter.

If the patient cannot pass urine on reassessment,

a catheter is left in situ. There is, however, no

protocol for catheter removal. The catheter will

usually remain in place for 1 to 2 days. In our study,

the mean duration of urinary catheterisation was

2.35 (range, 1-15) days (Fig 3). If the patient fails

to manage without a urinary catheter, a urological

referral is made. This is not ideal as the patient must

then remain an in-patient while awaiting urological

opinion. We believe close liaison with the urologist

should be established to enable such patients to be

discharged and subsequently assessed in a urology

out-patient clinic.

There were some important negative findings

in our study. Most Caucasian studies reveal

that women remain in hospital longer than men

following TKR.3 5 This has been reported to be due

to the different gender roles in the family: men could

go home earlier because they were more likely to

be looked after by their partner.19 The situation in

Hong Kong is different. Children usually live with or

close to their parents for cultural and social reasons.

Patients having TKR are cared for by their children,

not their partner; this eliminates the effect of gender

on LOS.

We did not find a statistically significant

contribution of drain insertion. We hypothesise that

drain insertion decreases haematoma collection and

knee effusion and improves the range of movement

and function. Since adequate knee function is

required for discharge, LOS could be reduced. The

results in this study, however, contradicted this

hypothesis.

Evaluating predictive factors for LOS after

TKR is the starting point to improve our current

practice. Based on this study, we need to establish a

protocol to wean patients off a urinary catheter. Early

prediction of high-risk patients who will require

longer hospitalisation provides the opportunity

for better preoperative counselling, anticipation of

escalated care, and proactive discharge planning.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature,

with results highly dependent on the accuracy of

documentation. We have not precisely recorded the home care status of the patient and the experience of

the principal surgeon, as a result these are not used

as a covariate in the analysis of our study. The results

also reflect the clinical practice of a single centre

and may not be generalised to represent the whole

population. A territory-wide joint replacement

registry could help to analyse predictors of LOS that

are specific to Hong Kong.

Conclusion

Factors that significantly influence LOS following

TKR are advanced age; ASA class 3; bilateral

operation; in-patient complications; and the need

for blood transfusion, postoperative ICU admission,

and urinary catheterisation. Identifying these factors

will help improve our clinical practice to reduce the

LOS and associated cost.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Kin-hoi Wong

of North District Hospital for his advice regarding

statistical analysis.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Yan CH, Chiu KY, Ng FY. Total knee arthroplasty for

primary knee osteoarthritis: changing pattern over the past

10 years. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:20-5.

2. Lee QJ, Mak WP, Wong YC. Mortality following primary

total knee replacement in public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:237-41.

3. Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay

and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement

surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop

2008;79:168-73. Crossref

4. Ong PH, Pua YH. A prediction model for length of stay

after total and unicompartmental knee replacement. Bone

Joint J 2013;95:1490-6. Crossref

5. Carter EM, Potts HW. Predicting length of stay from an

electronic patient record system: a primary total knee

replacement example. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak

2014;14:26. Crossref

6. van den Belt L, van Essen P, Heesterbeek PJ, Defoort KC.

Predictive factors of length of hospital stay after primary

total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol

Arthrosc 2015;23:1856-62. Crossref

7. Halawi MJ, Vovos TJ, Green CL, Wellman SS, Attarian

DE, Bolognesi MP. Preoperative predictors of extended

hospital length of stay following total knee arthroplasty. J

Arthroplasty 2015;30:361-4. Crossref

8. Raut S, Mertes SC, Muniz-Terrera G, Khanduja V. Factors

associated with prolonged length of stay following a total

knee replacement in patients aged over 75. Int Orthop

2012;36:1601-8. Crossref

9. El Bitar YF, Illingworth KD, Scaife SL, Horberg JV, Saleh

KJ. Hospital length of stay following primary total knee

arthroplasty: data from the nationwide inpatient sample

database. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1710-5. Crossref

10. Lozano LM, Tió M, Rios J, et al. Severe and morbid obesity

(BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) does not increase surgical time and

length of hospital stay in total knee arthroplasty surgery.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:1713-9. Crossref

11. Jonas SC, Smith HK, Blair PS, Dacombe P, Weale AE.

Factors influencing length of stay following primary total

knee replacement in a UK specialist orthopaedic centre.

Knee 2013;20:310-5. Crossref

12. Cohen RG, Forrest CJ, Benjamin JB. Safety and efficacy

of bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty

1997;12:497-502. Crossref

13. Jain S, Wasnik S, Mittal A, Sohoni S, Kasture S. Simultaneous

bilateral total knee replacement: a prospective study of 150

patients. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2013;21:19-22. Crossref

14. Spicer E, Thomas GR, Rumble EJ. Comparison of the

major intraoperative and postoperative complications

between unilateral and sequential bilateral total knee

arthroplasty in a high-volume community hospital. Can J

Surg 2013;56:311-7. Crossref

15. Sheth DS, Cafri G, Paxton EW, Namba RS. Bilateral

simultaneous vs staged total knee arthroplasty: a

comparison of complications and mortality. J Arthroplasty

2016;31:212-6. Crossref

16. Guerin S, Collins C, Kapoor H, McClean I, Collins D. Blood

transfusion requirement prediction in patients undergoing

primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Transfus Med

2007;17:37-43. Crossref

17. Kaw R, Pasupuleti V, Walker E, Ramaswamy A, Foldvary-Schafer N. Postoperative complications in patients with

obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2012;141:436-41. Crossref

18. Auckley D, Bolden N. Preoperative screening and

perioperative care of the patient with sleep-disordered

breathing. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2012;18:588-95. Crossref

19. Baker DW, Hasnain-Wynia R, Kandula NR, Thompson

JA, Brown ER. Attitudes toward health care providers,

collecting information about patients’ race, ethnicity, and

language. Med Care 2007;45:1034-42. Crossref

A video clip showing transcatheter aortic valve implantation technique

A video clip showing transcatheter aortic valve implantation technique

A video clip showing triplet pregnancy with fetal reduction skills

A video clip showing triplet pregnancy with fetal reduction skills