Development and optimisation strategies for a nomogram-based predictive model of malignancy risk in thyroid nodules

Hong Kong Med J 2026;32:Epub 30 Jan 2026

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE (HEALTHCARE IN CHINA)

Development and optimisation strategies for a

nomogram-based predictive model of malignancy

risk in thyroid nodules

Peng He, MD, PhD1 #; Yu Liang, MD2 #; Yuan Zou, MD1; Zhou Zou, BM3; Bo Ren, MD1; Shan Peng, MD4; Hongmei Yuan, MD, PhD1; Qin Chen, MD2

1 Department of Ultrasound Medicine and Ultrasonic Medical Engineering

Key Laboratory of Nanchong City, Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan

Medical College, Nanchong, China

2 Department of Ultrasound, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and

Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, University of

Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China

3 Department of Orthopedics, Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and

Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, University of

Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China

4 Department of Rehabilitation, Second Clinical College of North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China

# Equal contribution

Corresponding author: Dr Yuan Zou (zouyuanxiao@163.com)

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to develop and

validate a clinical prediction model to assist

radiologists in optimising the diagnostic classification

of the Chinese Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data

System (C-TIRADS).

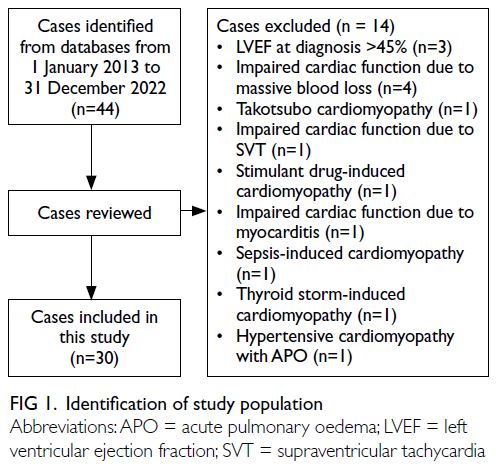

Methods: A total of 1659 patients from two hospitals

were included in this study. The derivation cohort

comprised 909 patients for model development

and internal validation, while 750 patients

formed the external validation cohort. A binary

logistic regression model was constructed. Model

performance in the derivation set was evaluated

using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

and visualised with a nomogram. In the external

validation set, ROC and calibration curves were

used to assess discrimination and calibration.

Results: The original C-TIRADS category, abnormal

cervical lymph node sonographic findings,

and changes in thyroid nodule size emerged as

significant predictors of C-TIRADS optimisation.

The optimised nomogram demonstrated an area

under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.730 (95% confidence

interval=0.697-0.762), with a sensitivity of 63.2%,

specificity of 74.9%, and overall accuracy of 67.7%

for predicting optimisation. Using probability

thresholds of ≥60% to recommend an upgrade and

<30% to recommend a downgrade, the calibration

curve showed good agreement, and decision curve

analysis demonstrated a favourable net clinical

benefit. External validation confirmed excellent discrimination (AUC=0.865; 95% confidence

interval=0.839-0.891).

Conclusion: An optimised C-TIRADS model that

integrates imaging features of thyroid nodules with

clinical risk factors may aid radiologists in improving

the diagnostic efficiency and clinical utility of the

TIRADS classification.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first study to integrate clinical risk factors with imaging features to optimise the Chinese Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (C-TIRADS) classification.

- This work established a risk threshold–based decision-making framework to guide C-TIRADS classification adjustments.

- External validation demonstrated the model’s generalisability across diverse clinical settings.

- Our model improved diagnostic precision through the integration of imaging and clinical risk factors.

- This research has the potential to optimise resource allocation and reduce interobserver diagnostic variability.

Introduction

Thyroid nodules are a common clinical finding,

with a prevalence of approximately 4% to 7% in the

general population, and are most often detected by ultrasonography.1 2 Although most thyroid

nodules are benign, distinguishing malignant

from benign nodules remains a clinical priority to

avoid unnecessary procedures and ensure timely intervention.3 To standardise risk stratification,

various Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data Systems

(TIRADS) have been developed,4 5 including the

ACR-TIRADS (American College of Radiology),6 the

K-TIRADS (Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology),7

and the European Thyroid Association.8 Recognising

the need for a system tailored to the Chinese

healthcare context, the Chinese Artificial Intelligence

Alliance for Thyroid and Breast Ultrasound proposed

the Chinese TIRADS (C-TIRADS) in 2021.2

However, existing TIRADS models primarily focus

on sonographic characteristics and often overlook

relevant clinical risk factors (eg, patient age, sex,

and cervical lymph node [LN] involvement).9 In

clinical practice, radiologists frequently incorporate

such clinical information into their assessments,

contributing to inconsistency and variability in

TIRADS classification.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma accounts for

approximately 80% to 90% of all thyroid cancers and

is typically characterised by indolent behaviour.10 11 A

substantial proportion of new cases involve papillary

thyroid microcarcinoma, defined as tumours

measuring less than 10 mm in diameter, which

generally carry a favourable clinical prognosis.12

Increasing recognition of the indolent nature

of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma has raised

concerns regarding potential overdiagnosis and overtreatment. However, current risk stratification

strategies that rely solely on imaging features may

either overestimate or underestimate malignancy

risk, depending on the patient’s broader clinical

context. Approaches that incorporate clinical risk

factors into TIRADS classification could address

these limitations and enhance diagnostic accuracy,

supporting more individualised patient management.

This study aimed to develop and externally

validate a predictive model that integrates both

imaging characteristics and clinical risk factors to

refine the C-TIRADS classification system. To our

knowledge, this is the first nomogram-based model

to incorporate clinical risk factors into the C-TIRADS

framework. The tool is designed to assist radiologists

in improving diagnostic consistency and supporting

more informed and individualised clinical decision

making in the management of thyroid nodules.

Methods

Study design and population

This retrospective diagnostic study included patients

with thyroid nodules who underwent surgical

resection at two tertiary hospitals in China. The

derivation cohort comprised patients treated at

Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital from January to

December 2022, while the external validation cohort

was drawn from Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan

Medical College during the same period. Inclusion

criteria were: (1) thyroid nodules confirmed by

postoperative pathology and (2) preoperative

ultrasonography of the thyroid and cervical LNs with

complete imaging and clinical records. Exclusion

criteria were: (1) unclear pathological diagnosis;

(2) incomplete clinical data; or (3) poor-quality

ultrasound images.

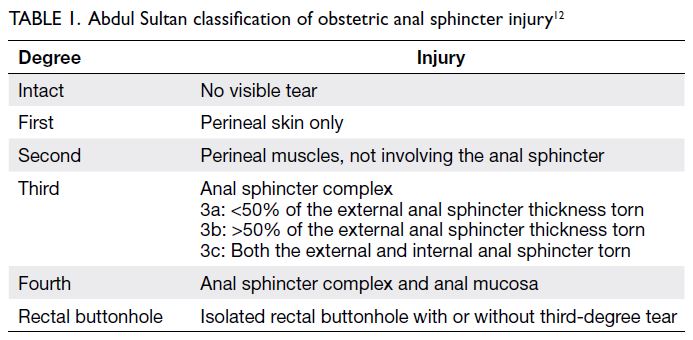

Imaging evaluation and classification

Two junior radiologists, blinded to clinical and

pathological information, independently classified

all nodules according to the C-TIRADS criteria.

Subsequently, two senior radiologists re-evaluated

the cases and adjusted the classifications based on

additional clinical risk factors, including patient

demographics and cervical LN findings. Any

modification from the initial C-TIRADS classification

was defined as ‘classification optimisation’ (*C-TIRADS),

encompassing both upgrades and

downgrades.

Data collection

Structured data collection forms were used to record

clinical and sonographic variables. The collected data

included patient sex, age, nodule size, number of

nodules, C-TIRADS classification, and the presence

of abnormal cervical LNs on ultrasonography.

Predictor variables

Sonographic features that directly determine the

C-TIRADS score (such as solidity, echogenicity,

aspect ratio, microcalcification, and margin

irregularity) were not included independently in the

multivariable analysis to avoid collinearity. Based on

clinical relevance and univariate regression analysis,

six predictors were selected for model development,

namely, patient sex, age-group (≤40, 40-60, and >60

years),13 14 nodule size, number of nodules (single vs

multiple), presence of abnormal cervical LNs, and

original C-TIRADS classification.

Model development and internal validation

A binary logistic regression model was developed

using the derivation cohort from Sichuan Provincial

People’s Hospital (n=909). For categorical variables

with more than two levels, dummy variables were

created. The C-TIRADS category 5 was used as the

reference group as it represents the highest level

of suspicion and the most definitive management

pathway (surgical resection), making it an appropriate

clinical baseline to estimate relative malignancy risk

and the need for reclassification. Model performance

in the derivation cohort was evaluated using the

area under the receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve (AUC), and calibration was assessed by

comparing predicted probability (PP) with observed

outcomes using calibration plots.

We emphasise that the primary outcome

variable for model training was the pathological

diagnosis (binary: malignant vs benign). The C-TIRADS

optimisation, defined as upgrading or

downgrading the original category based on PP

thresholds, was a post-model clinical decision rule

applied to the model output, not the outcome used

for model development.

Internal validation was performed using

bootstrap resampling with 1000 samples to obtain

bias-corrected estimates of model performance and

95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A fixed random

seed was set to ensure reproducibility. The bias-corrected

C-statistic was 0.728, compared with the

original apparent performance of 0.730 (a difference

of 0.002), confirming the model’s stable discriminative

ability (online supplementary Table 1).

External validation

The final model was applied to the external cohort

from Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical

College (n=750) to evaluate its generalisability.

Model discrimination was evaluated by calculating

the AUC in the validation set, and calibration was

assessed using calibration curves.

Nomogram construction

A nomogram was developed based on the final multivariable regression model to provide a visual

tool for clinical application. Each predictor was

assigned a score, and the total score corresponded

to the PP of C-TIRADS classification optimisation.

Decision curve analysis and risk thresholds

Decision curve analysis and clinical impact curves

were used to evaluate the clinical utility of the

nomogram by quantifying the net benefit across

a range of threshold probabilities. Specifically,

the nomogram generates a PP indicating whether

a nodule’s original C-TIRADS classification

should be modified after integrating clinical

information. For clinical decision making, we pre-specified

probability cut-offs: PP ≥60% (upgrade),

PP <30% (downgrade), and PP ≥30% but <60%

(unchanged). Based on these thresholds, the model’s

recommendations were translated into optimised

C-TIRADS categories, which were then compared

with radiologists’ optimisation decisions and surgical

pathology findings, as appropriate. These thresholds

are reported in the Results section and were applied

consistently across all performance tables

Model performance evaluation

To ensure consistent ROC analysis, all AUCs were calculated using continuous PPs rather than ordinal

risk categories. For the original C-TIRADS system,

the five-level ordinal classification was transformed

into a continuous malignancy probability score using

proportional-odds (ordinal logistic) regression. This

standard statistical method was employed to model

the ordered nature of the C-TIRADS categories and

to derive a continuous probability of malignancy

for each category, enabling fair comparison in ROC

analysis against other models. For the optimised

*C-TIRADS system, PPs were directly obtained

from the final multivariable logistic regression

model. The ROC curves and corresponding

AUCs were constructed using these continuous

predictions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and data visualisation were

performed using SPSS (Windows version 26.0; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], United States) and RStudio

(version 2022). Categorical variables were reported

as number of cases or percentages, with group

comparisons conducted using Chi squared test or

Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Multivariable

logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify

independent predictors. Model discrimination

was evaluated using ROC curves, while calibration

curves were used to assess model accuracy. Clinical

decision and impact curves were established to

assess practical clinical utility. A two-tailed P value

of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

All models were trained to predict pathological

malignancy. The optimised *C-TIRADS

classifications presented here were derived by

applying predefined probability thresholds to the

model’s malignancy predictions.

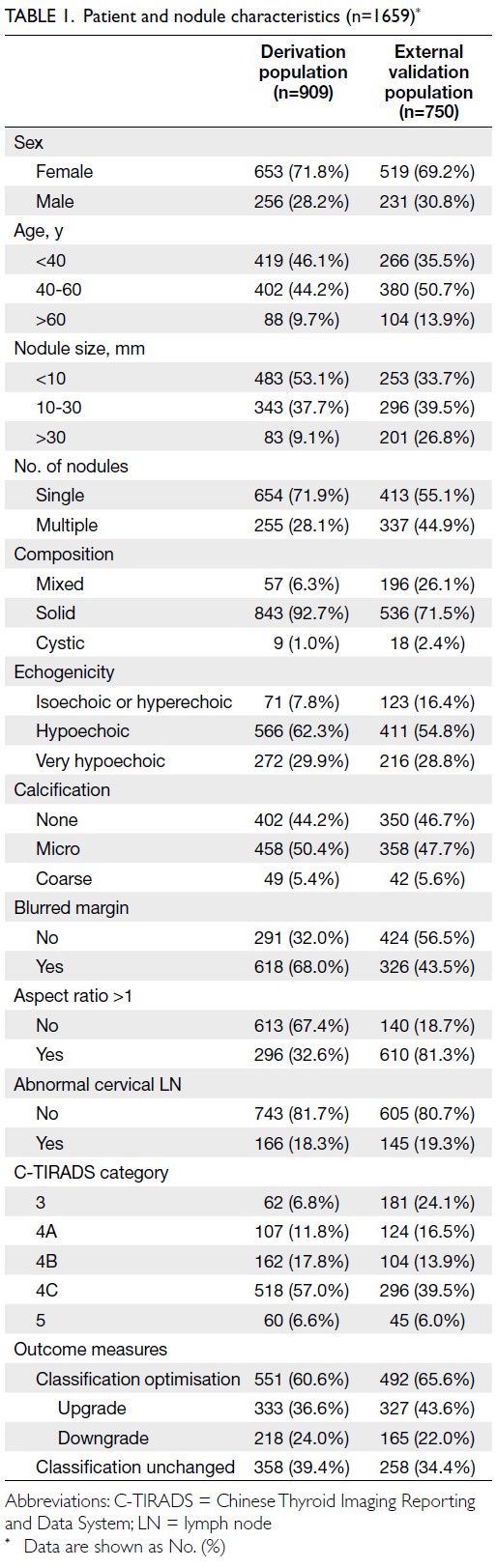

A total of 1659 patients with thyroid nodules

were included in the study, comprising 909 patients

in the derivation cohort and 750 in the external

validation cohort. In the derivation cohort, 71.8%

of patients were women, and the majority (90.8%)

had nodules measuring ≤30 mm. Approximately

81.7% of patients showed no abnormal cervical

LNs on ultrasonography. The rate of C-TIRADS

optimisation was 60.6%. In the external validation

cohort, similar distributions were observed, with a

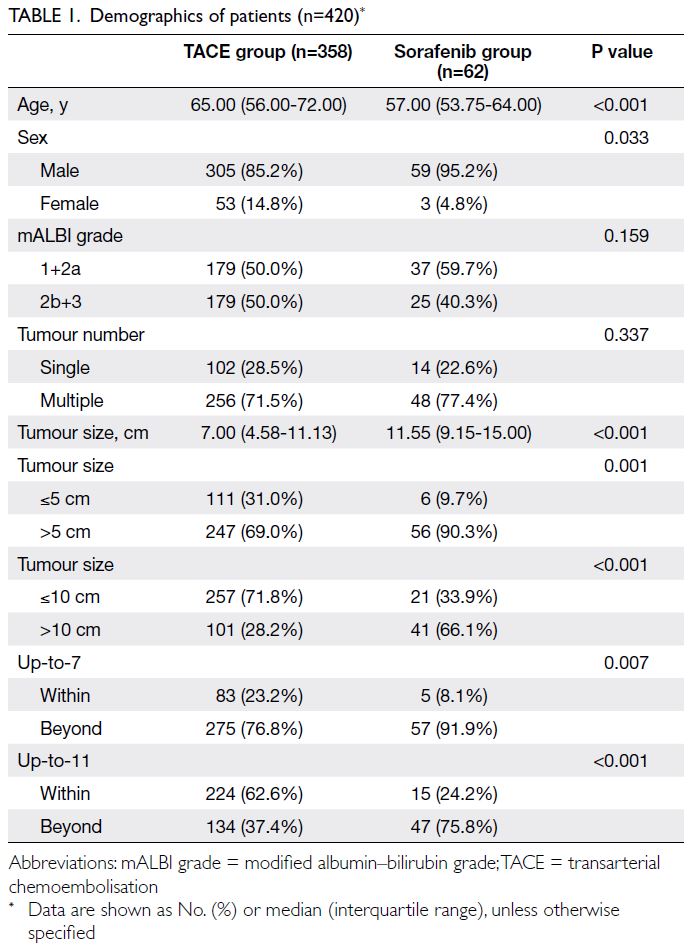

higher proportion of nodules >30 mm (Table 1).

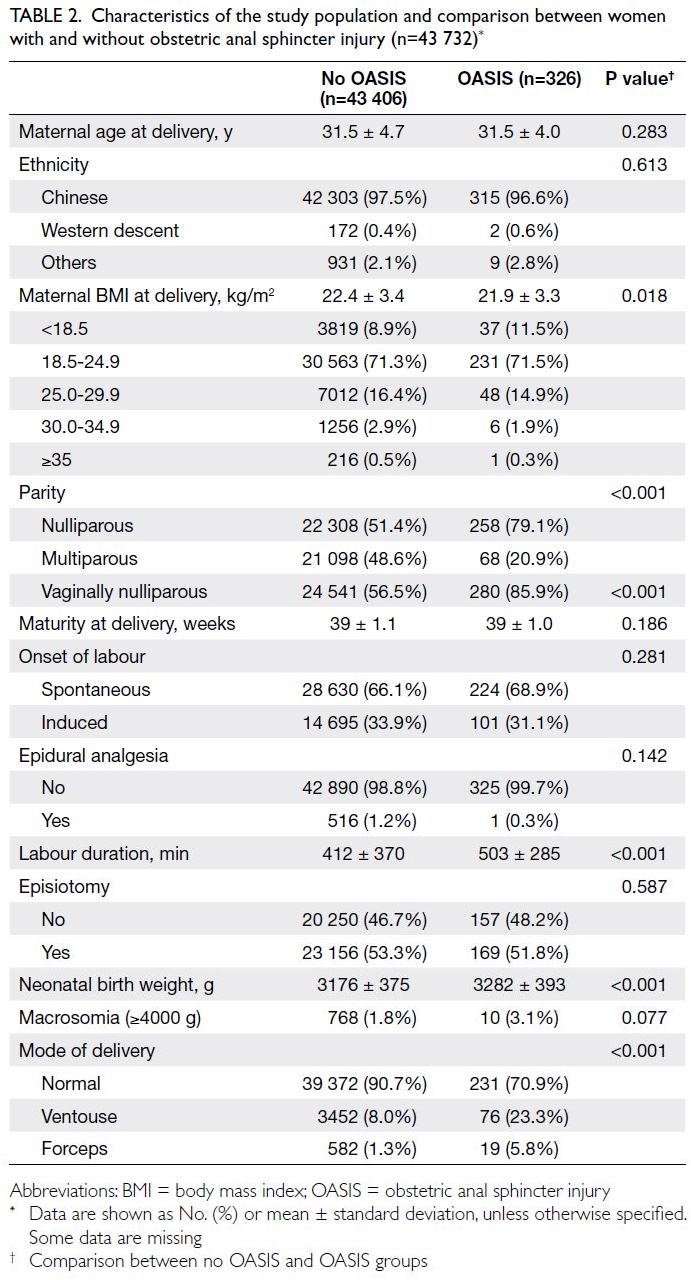

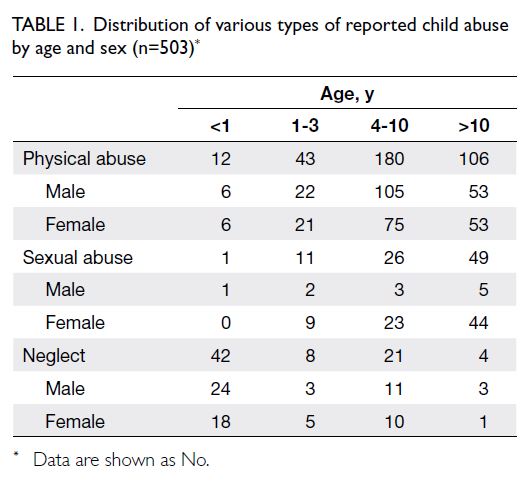

Univariate analysis

Univariate binary regression analysis revealed that

several variables were either significantly associated

(P<0.05) or showed a trend towards association

(0.05 < P < 0.1) with C-TIRADS optimisation. These

variables included patient sex, age, nodule size

(10-30 mm), number of nodules, solid composition,

blurred margins, aspect ratio >1, abnormal cervical

LNs, and C-TIRADS category (Table 2 and online supplementary Table 2).

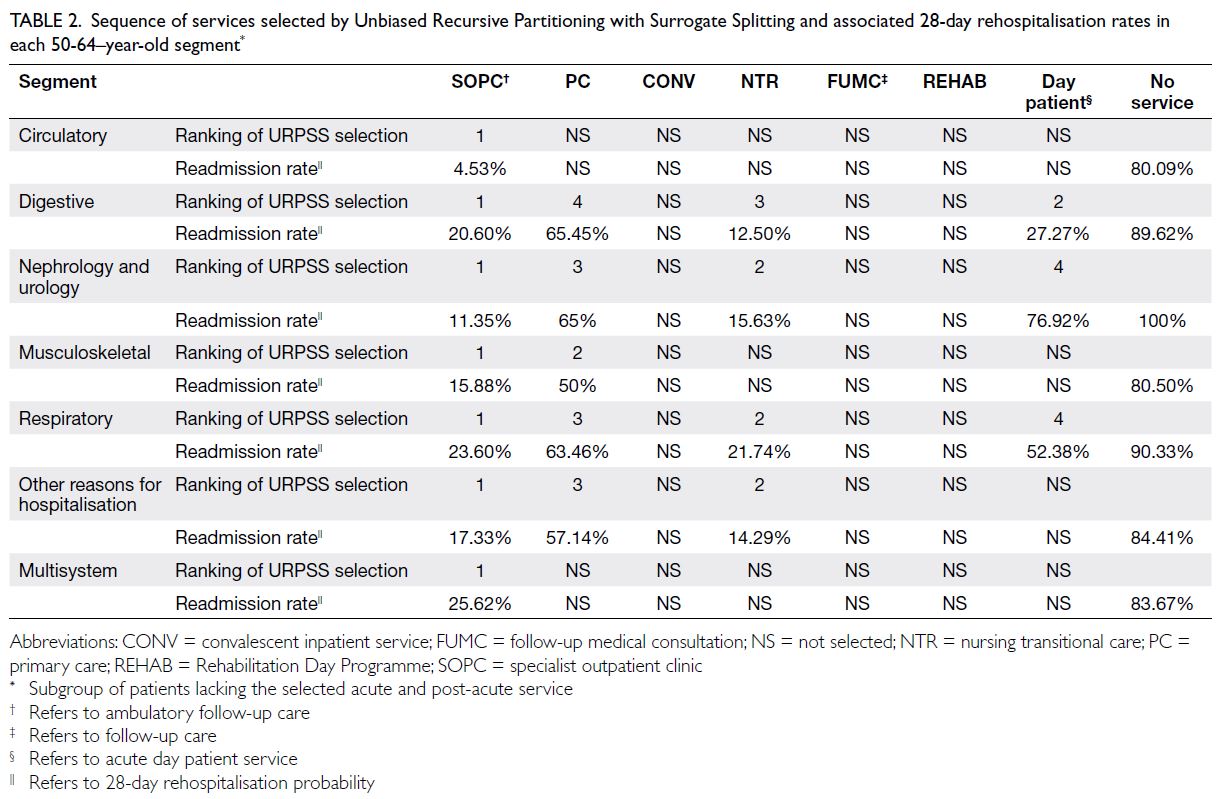

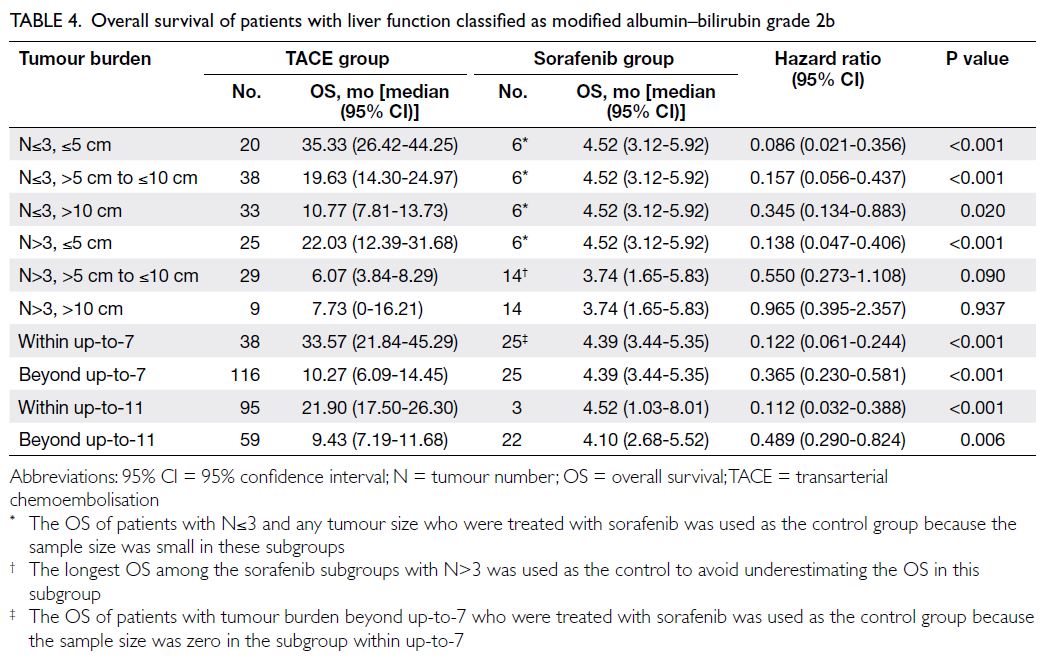

Table 2. Predictor distribution and univariate logistic regression odds ratios for malignancy (n=909)

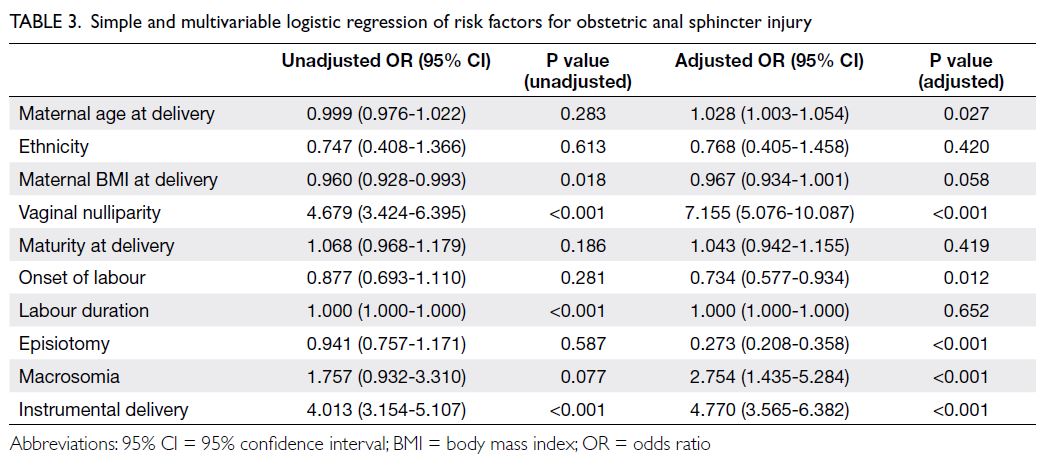

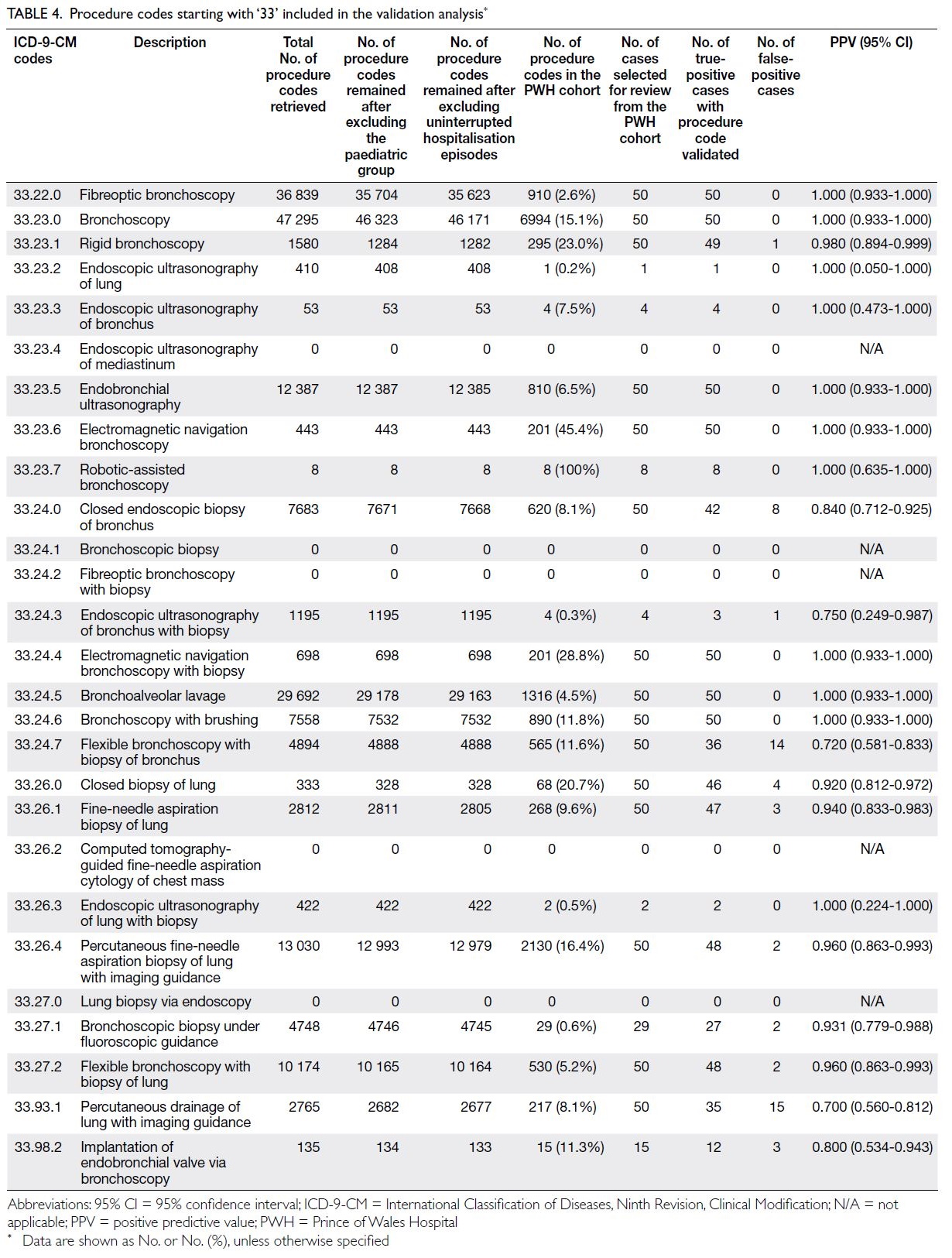

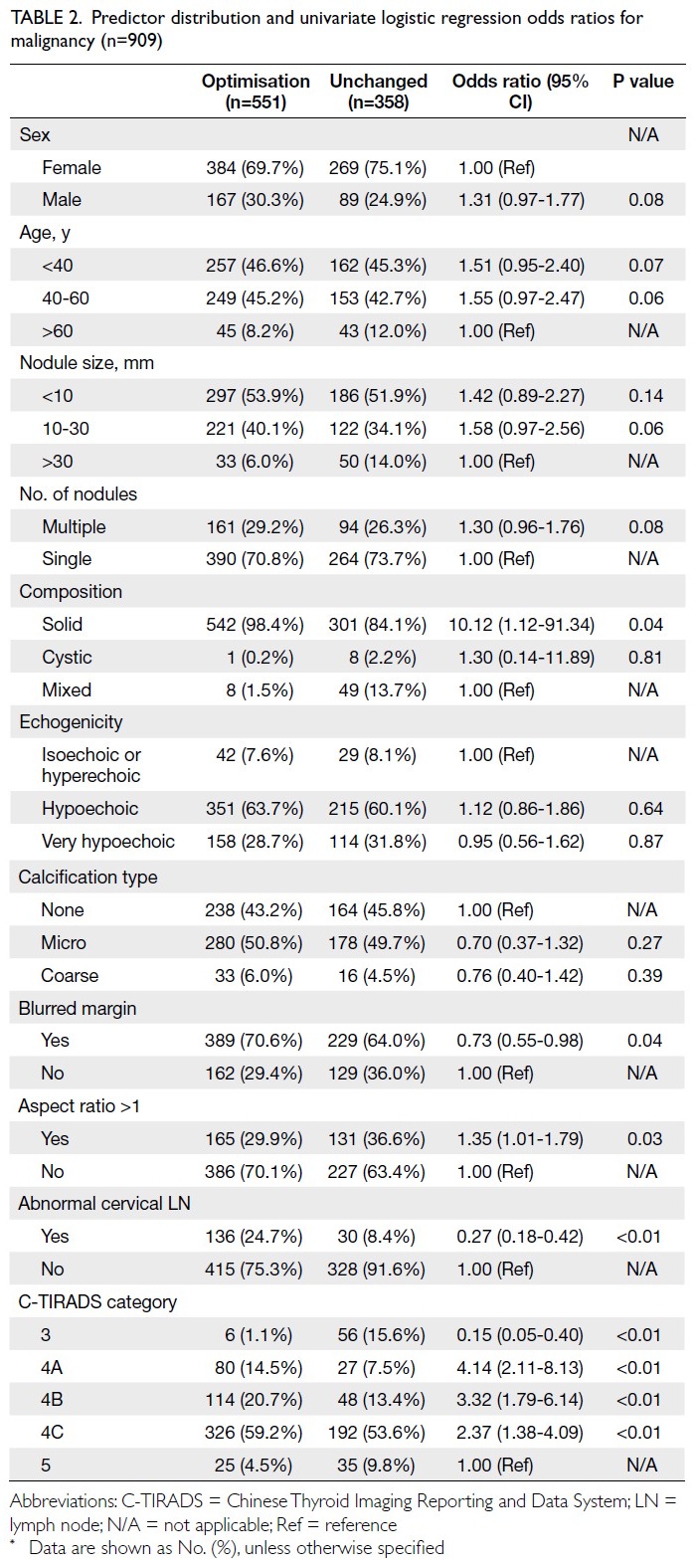

Multivariable model development

A multivariable binary logistic regression model

was developed to identify independent predictors

associated with C-TIRADS optimisation. Six

predictors were independently associated with

the outcome. The key predictors of C-TIRADS

optimisation were male sex, age 40 to 60 years,

thyroid nodule size (per 1-mm increase), multiple

thyroid nodules, presence of abnormal cervical

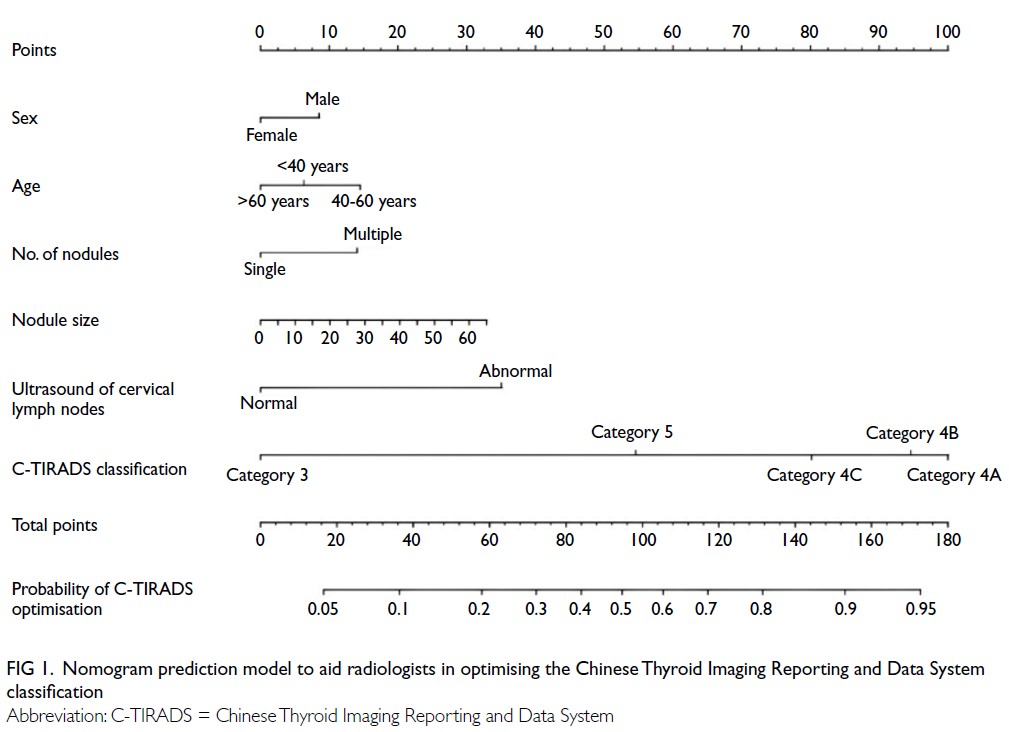

LNs, and original C-TIRADS 4A category (online supplementary Table 3). A nomogram model

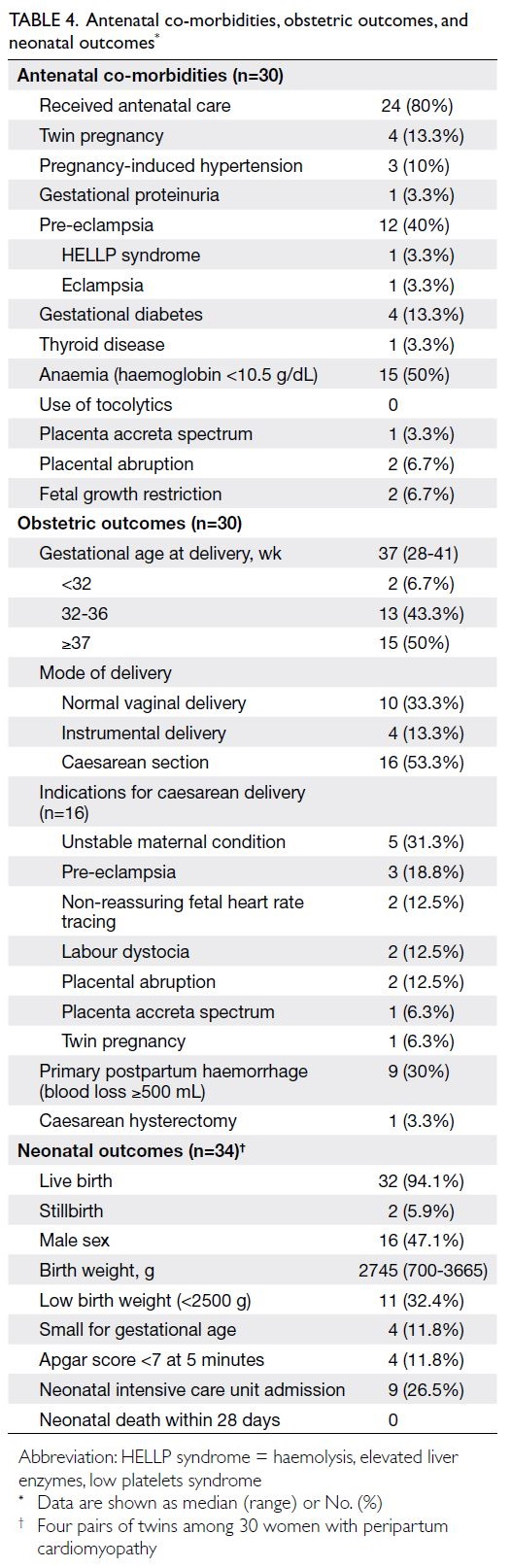

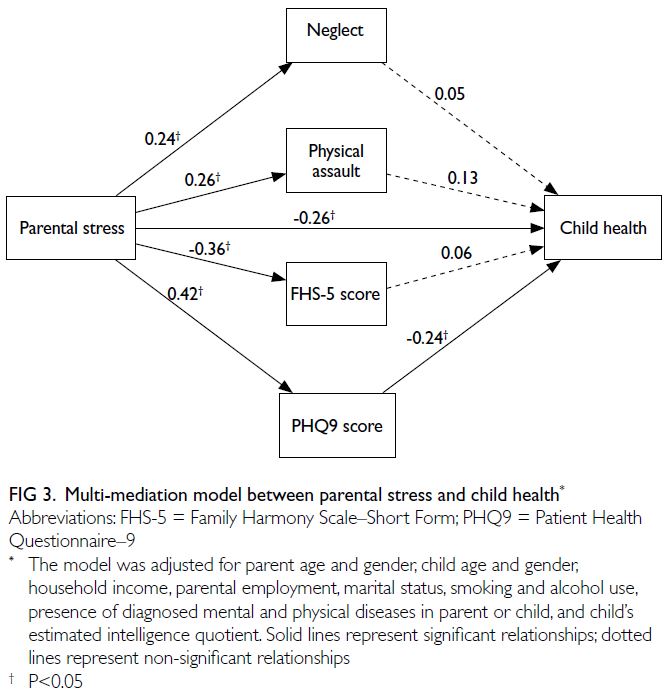

was constructed based on these six independent

predictors (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Nomogram prediction model to aid radiologists in optimising the Chinese Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System classification

Model performance in the derivation cohort

The model demonstrated good discrimination,

with an AUC of 0.730 (95% CI=0.697-0.762) in

the derivation cohort (online supplementary Fig a). Internal validation using 1000 bootstrap

samples yielded a bias-corrected C-statistic of

0.728, indicating stable model performance (online supplementary Table 1). Calibration curves showed

good agreement between PPs and observed

outcomes (online supplementary Fig b).

Diagnostic thresholds were evaluated to

stratify risk. A PP of ≥60% or <30% was considered indicative of a high likelihood of classification

change: a PP of ≥60% suggested upgrading, while a

PP of <30% suggested downgrading; PPs between

30% and 60% indicated that the classification was

likely to remain unchanged. A detailed summary

of sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy

across these thresholds is presented in online supplementary Table 4.

External validation

When applied to the external cohort, the model

achieved an AUC of 0.865 (95% CI=0.839-0.891)

[online supplementary Fig c], demonstrating

excellent generalisability. Calibration plots again

confirmed close agreement between predicted and

observed probabilities (online supplementary Fig d). At the 60% probability threshold, sensitivity was

85.0%, specificity was 69.0%, and overall accuracy

was 79.7% in the external validation cohort.

Diagnostic performance metrics across various

risk thresholds of the final prediction model were

analysed in the external validation population

(online supplementary Table 5).

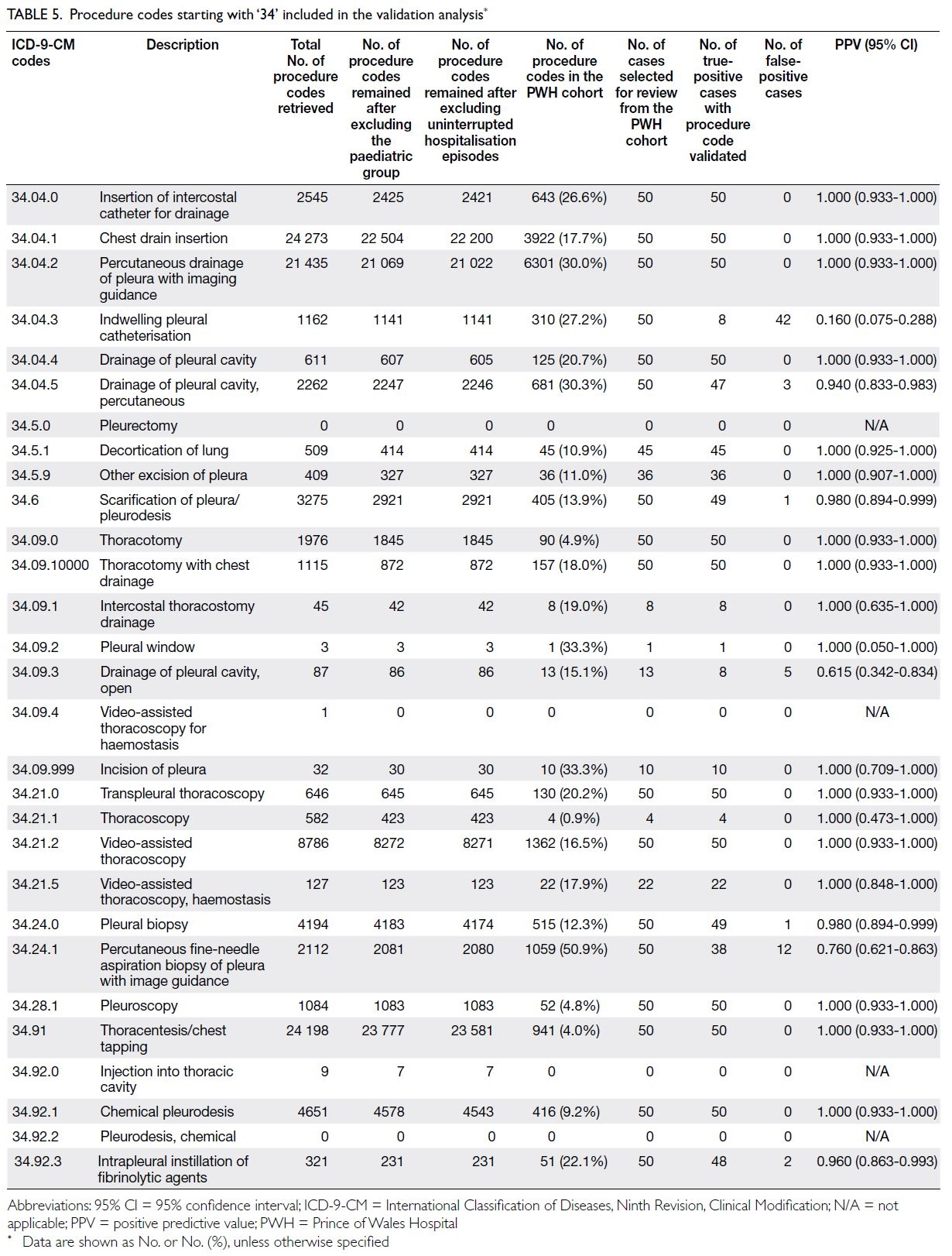

Clinical utility

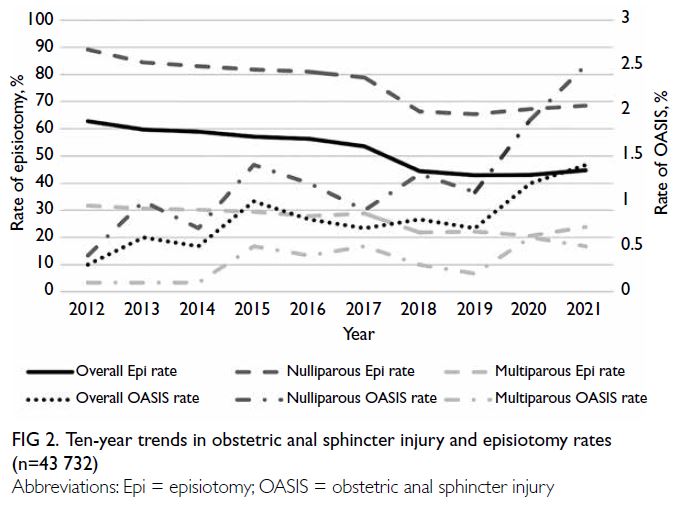

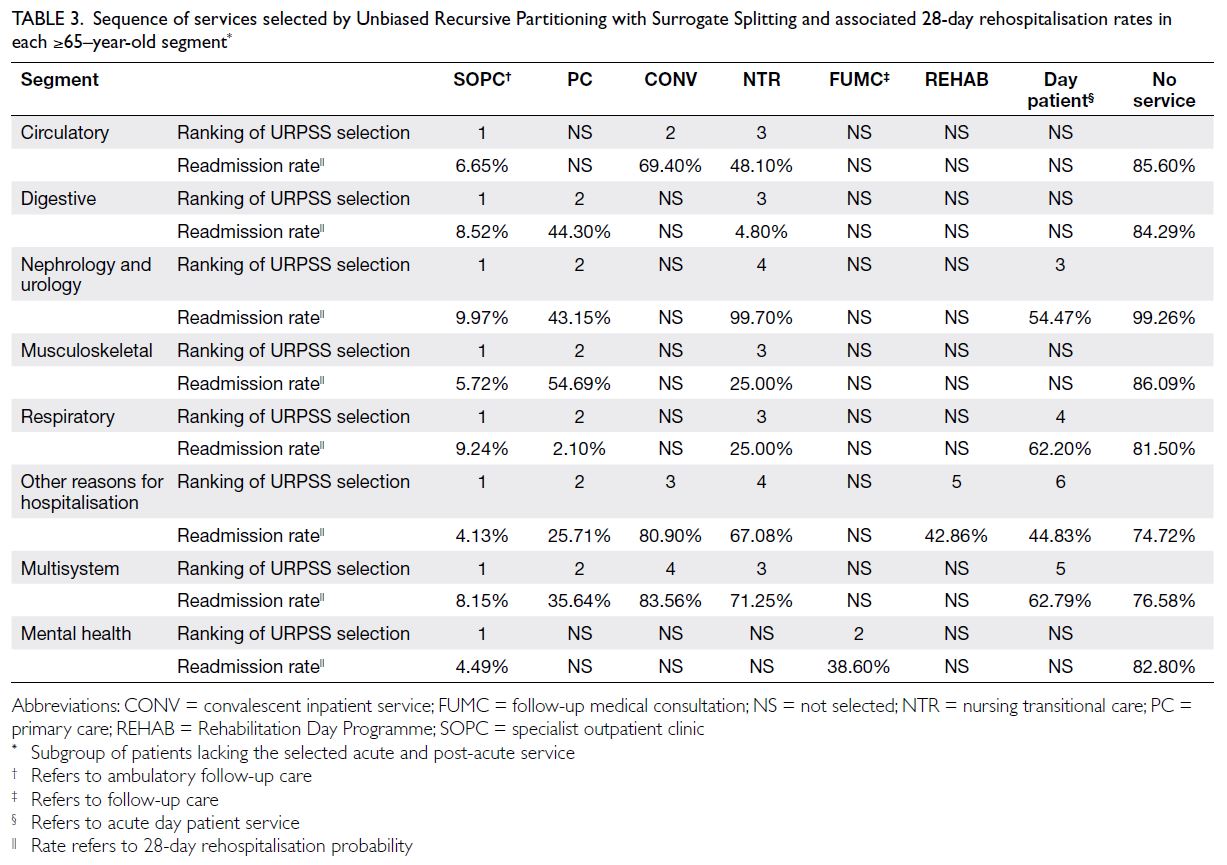

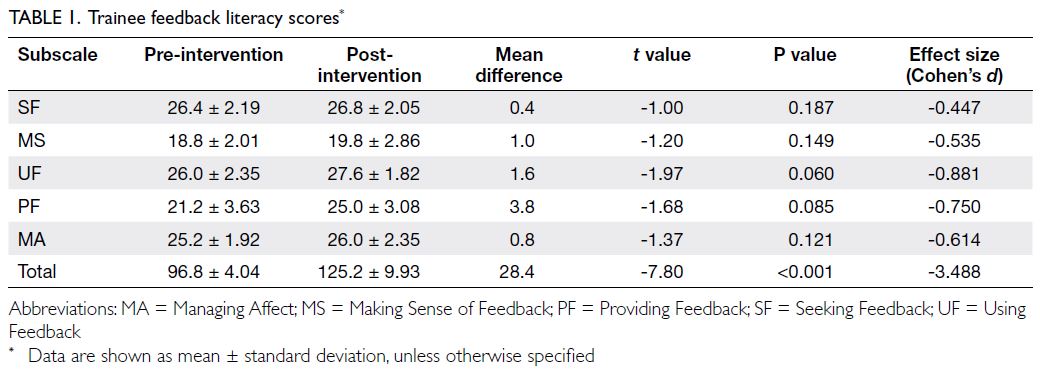

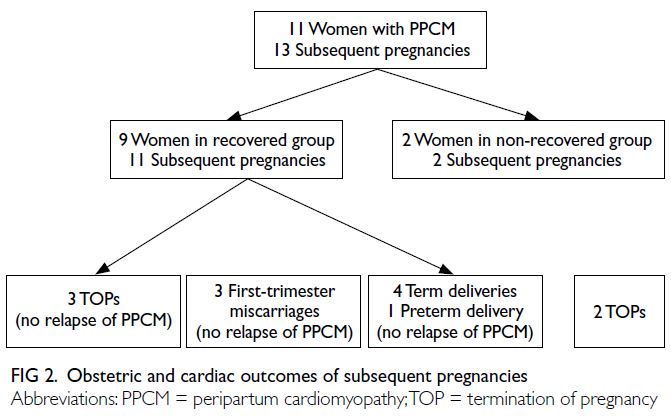

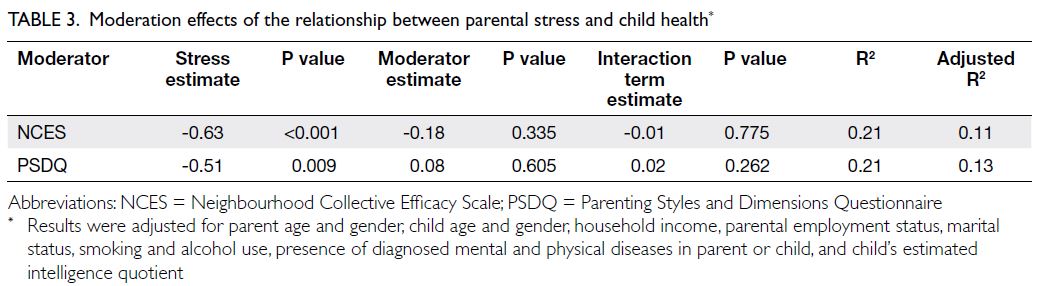

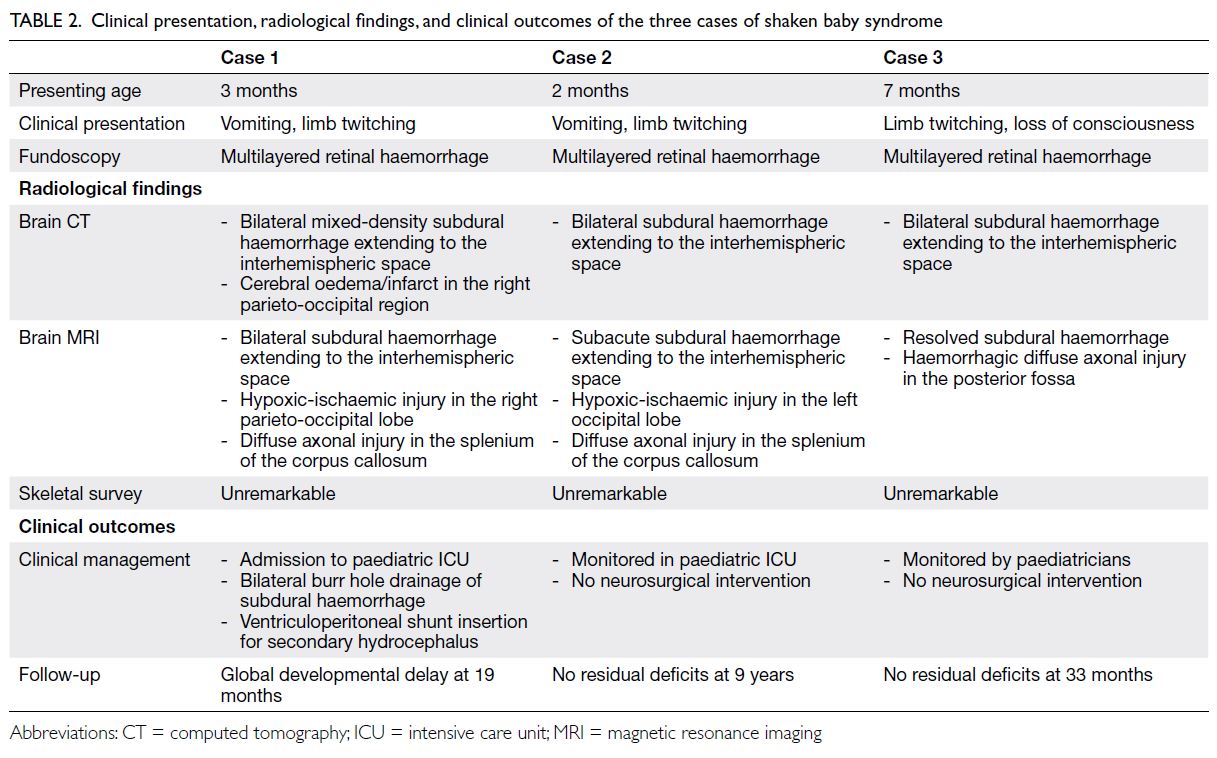

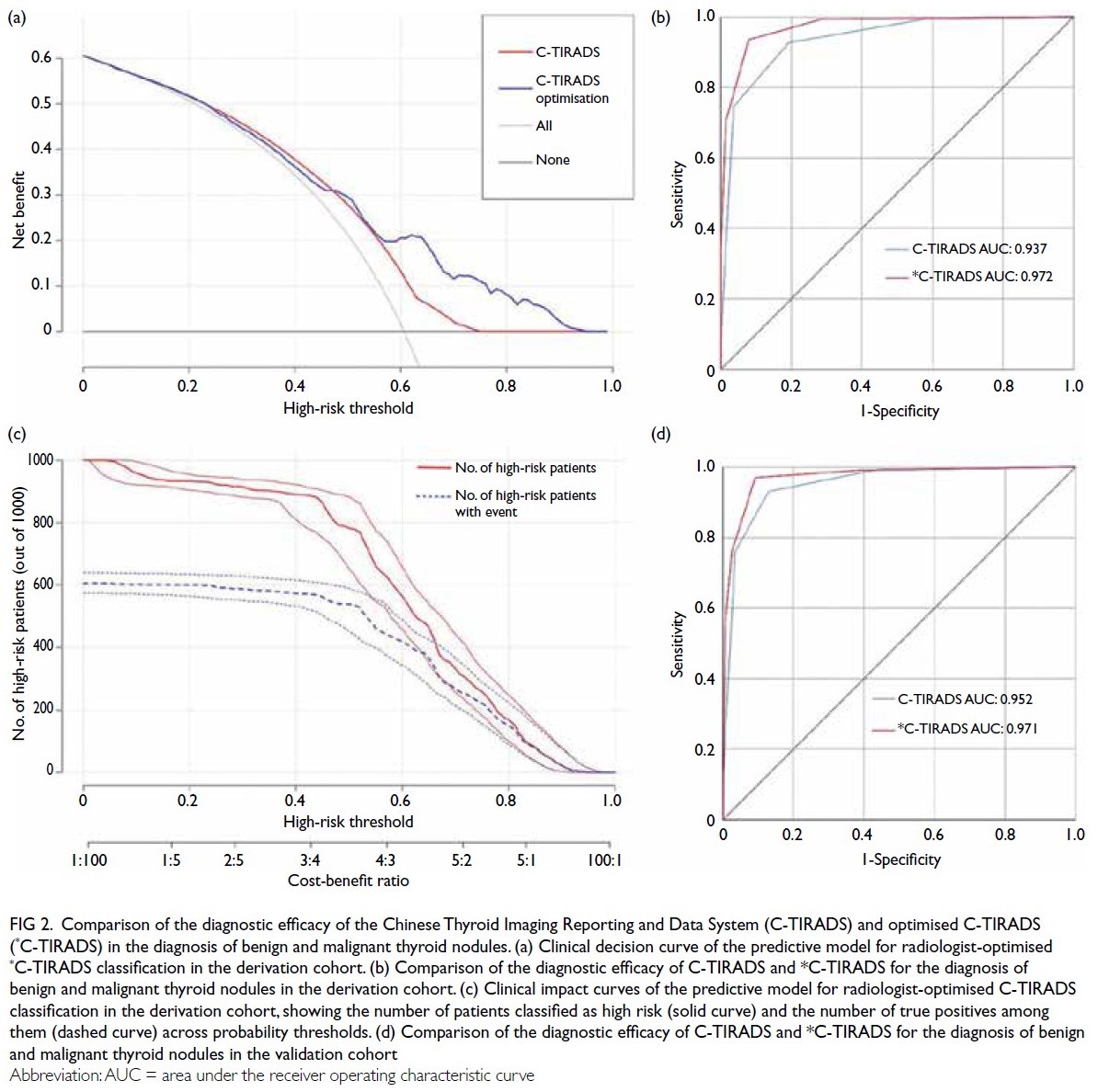

Decision curve analysis (Fig 2a) demonstrated that

the nomogram model provided greater net clinical

benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities

compared with treating all or no patients. The

clinical impact curve (Fig 2b) showed that the

number of true positives closely approximated the

predicted number across relevant thresholds. The

observed distribution of histopathological outcomes

was as follows: in the derivation cohort, 769 nodules

(84.6%) were confirmed malignant and 140 (15.4%)

were benign; in the validation cohort, 434 nodules

(57.9%) were malignant and 316 (42.1%) were benign.

Figure 2. Comparison of the diagnostic efficacy of the Chinese Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (C-TIRADS) and optimised C-TIRADS (*C-TIRADS) in the diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules. (a) Clinical decision curve of the predictive model for radiologist-optimised *C-TIRADS classification in the derivation cohort. (b) Comparison of the diagnostic efficacy of C-TIRADS and *C-TIRADS for the diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules in the derivation cohort. (c) Clinical impact curves of the predictive model for radiologist-optimised C-TIRADS classification in the derivation cohort, showing the number of patients classified as high risk (solid curve) and the number of true positives among them (dashed curve) across probability thresholds. (d) Comparison of the diagnostic efficacy of C-TIRADS and *C-TIRADS for the diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules in the validation cohort

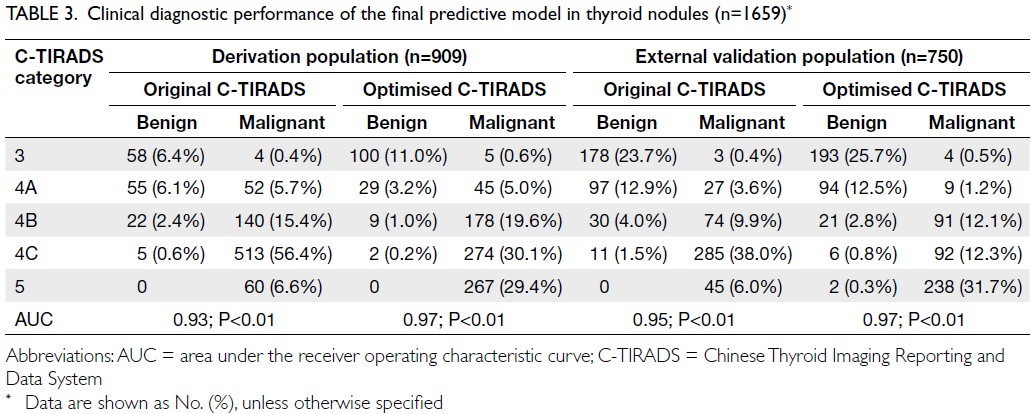

Comparison of diagnostic efficacy between

the original C-TIRADS and optimised C-TIRADS

classifications demonstrated superior performance

of the optimised model in both the derivation and

validation cohorts (Fig 2c and d, respectively).

The optimised classification achieved higher AUC

values for differentiating benign from malignant

nodules (AUC=0.97 vs 0.94 in the derivation cohort;

AUC=0.97 vs 0.95 in the external validation cohort).

The predictive model tended to improve C-TIRADS

classification by upgrading category 4A nodules

to category 4B or 4C, reflecting enhanced clinical

utility (Table 3 and Fig 2).

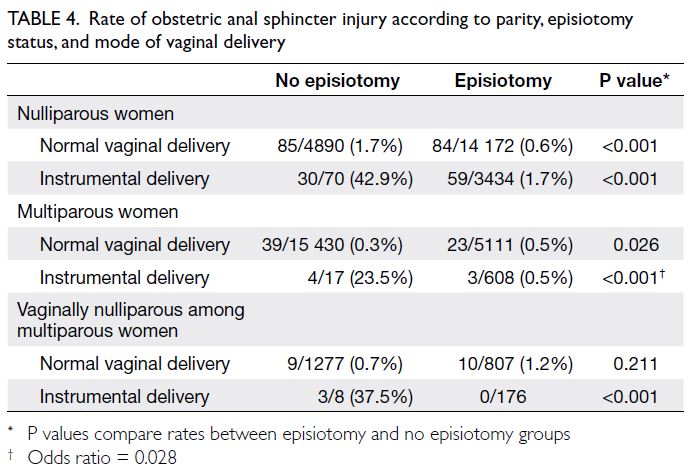

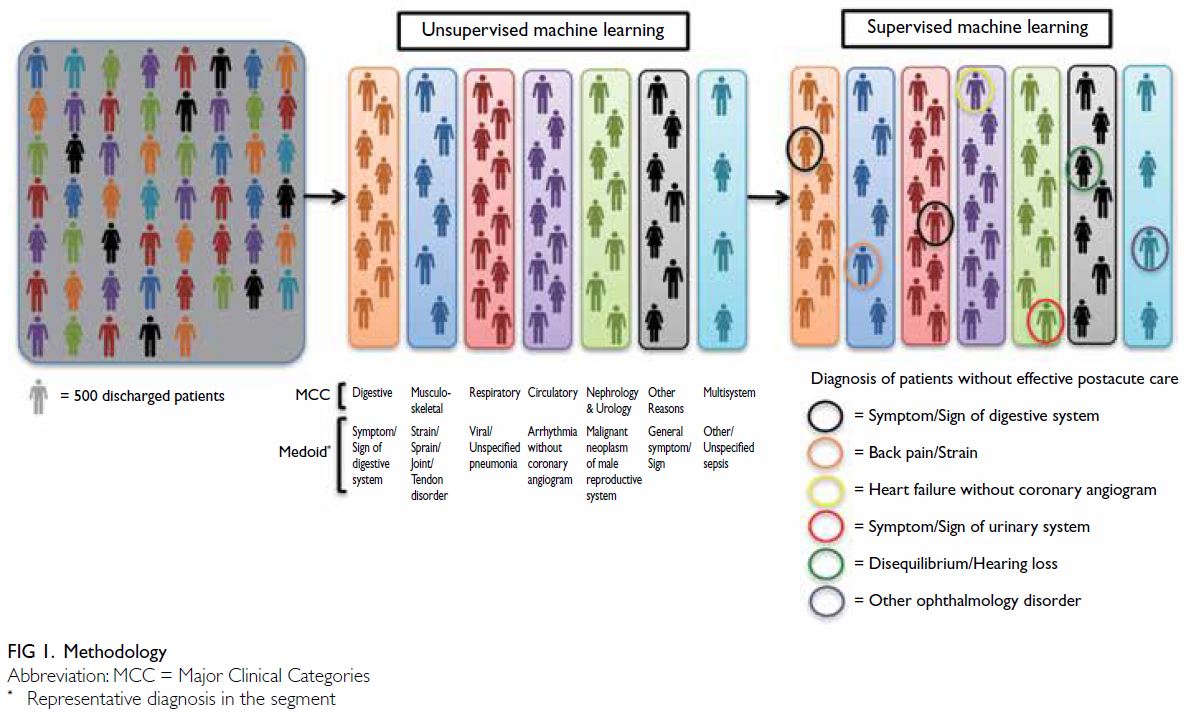

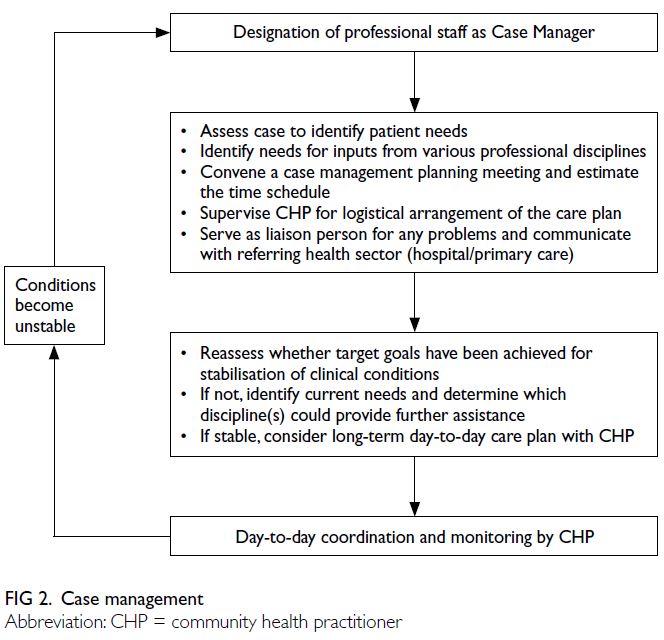

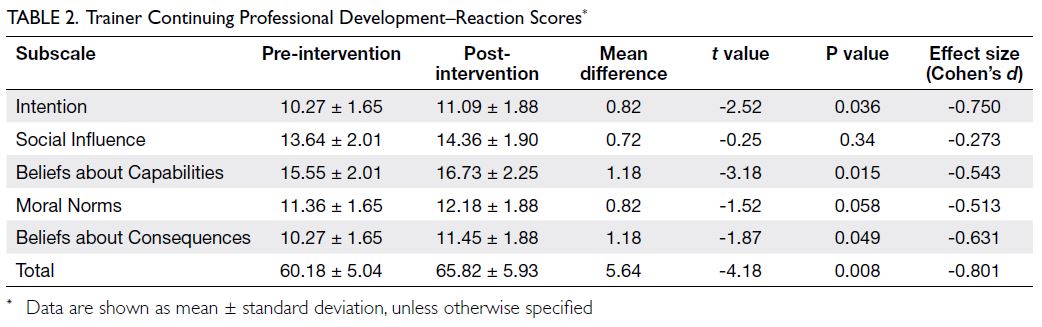

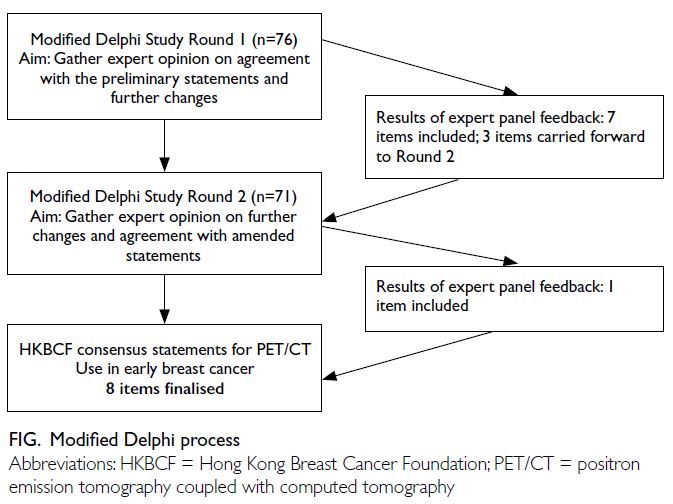

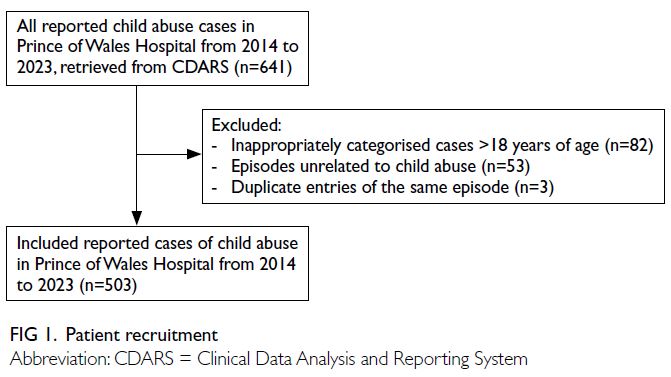

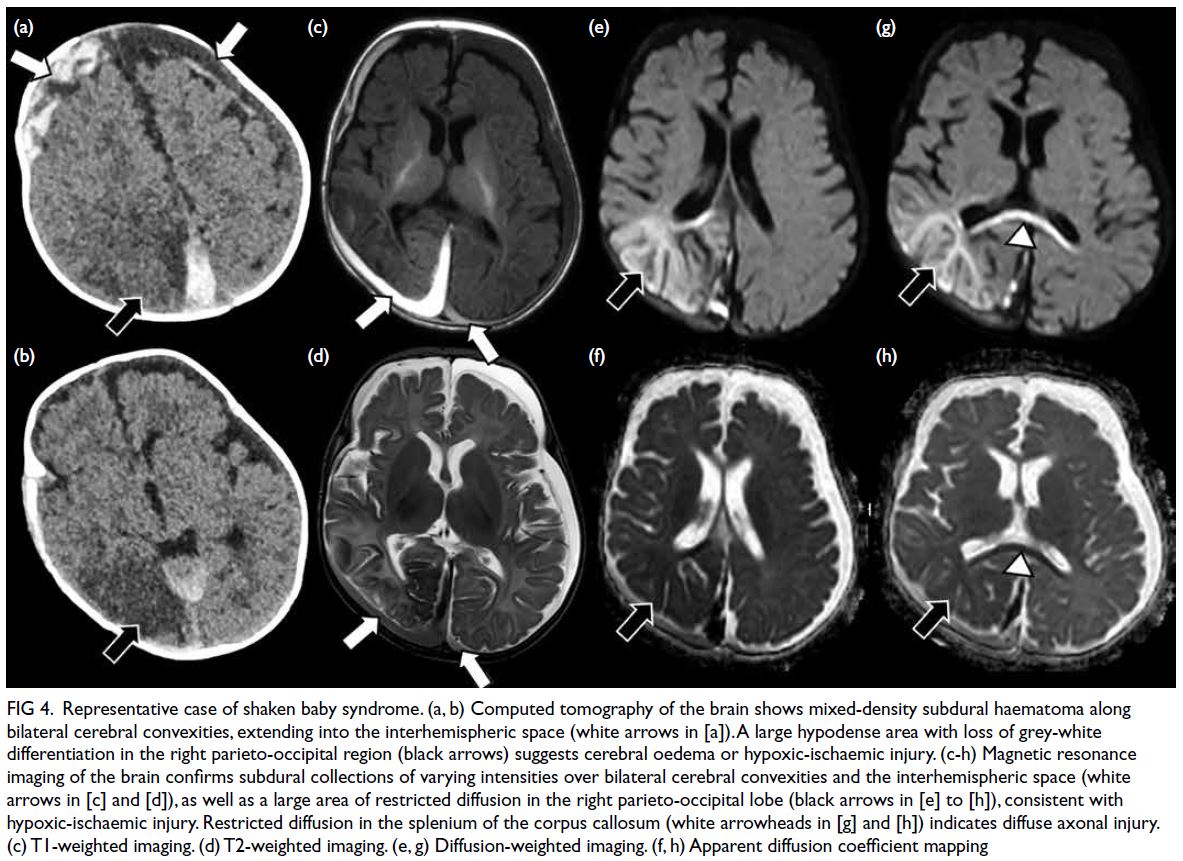

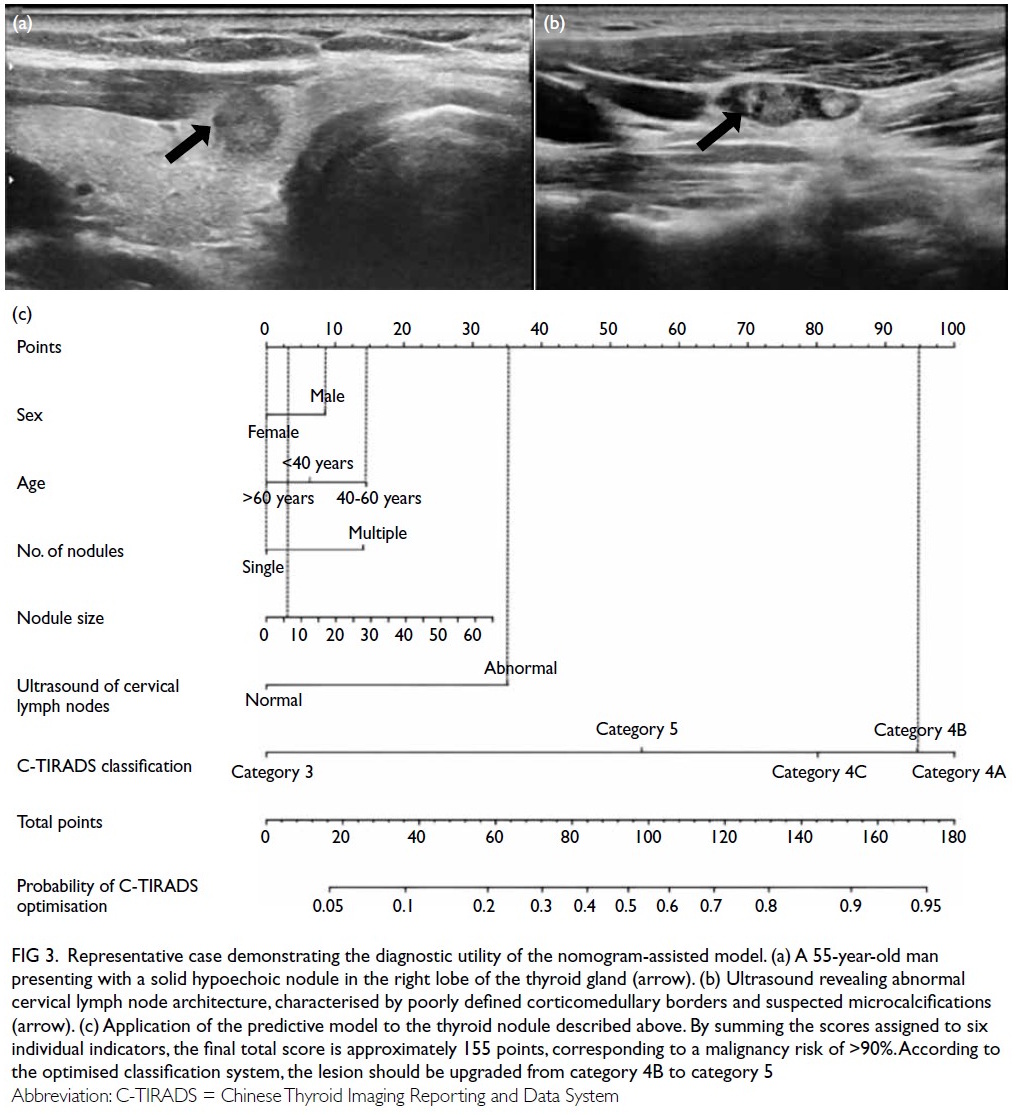

Application example of the nomogram model

A 55-year-old man underwent ultrasound

examination, which revealed a solid hypoechoic

thyroid nodule in the right lobe measuring

approximately 7.1 × 6.4 mm2 (Fig 3a). Simultaneously,

abnormal LNs were detected on the ipsilateral side of the neck, characterised by indistinct corticomedullary

differentiation and suspected microcalcifications

(Fig 3b). According to the conventional C-TIRADS

system, the nodule was initially classified as

category 4B. However, application of the nomogram

model yielded a cumulative score of 155 points,

corresponding to a malignancy risk of >90%. Based

on this result, the TIRADS category was optimised

and upgraded to category 5 (Fig 3c). Subsequent histopathological examination confirmed the

diagnosis of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma with

cervical LN metastasis.

Figure 3. Representative case demonstrating the diagnostic utility of the nomogram-assisted model. (a) A 55-year-old man presenting with a solid hypoechoic nodule in the right lobe of the thyroid gland (arrow). (b) Ultrasound revealing abnormal cervical lymph node architecture, characterised by poorly defined corticomedullary borders and suspected microcalcifications (arrow). (c) Application of the predictive model to the thyroid nodule described above. By summing the scores assigned to six individual indicators, the final total score is approximately 155 points, corresponding to a malignancy risk of >90%. According to the optimised classification system, the lesion should be upgraded from category 4B to category 5

Discussion

This study retrospectively analysed the sonographic

characteristics and clinical risk factors of 1659 thyroid

nodules from two large tertiary hospitals in western China, with the aim of optimising the C-TIRADS

classification. A predictive model integrating clinical

parameters and imaging features was developed and

externally validated, demonstrating high diagnostic

performance (AUC=0.865 in external validation)

and clinical benefit, as evidenced by decision curve

analysis.

Despite the widespread adoption of various

TIRADS frameworks globally,2 4 5 6 7 8 fundamental

methodological limitations persist. Current

models, such as ACR-TIRADS,6 primarily focus on ultrasound features and rely heavily on

consensus-driven rather than statistically validated

risk stratification systems.6 15 Although TIRADS

demonstrates robust sensitivity in clinical settings, its

specificity remains relatively limited.16 Interobserver

variability is another key concern—radiologists’

subjective interpretation of ultrasound features

can result in inconsistent classification outcomes.17

To address these limitations, various strategies

have been proposed, including the integration

of artificial intelligence techniques to reduce observer subjectivity.18 19 20 Artificial intelligence has

shown promise in matching or even surpassing the

specificity achieved by radiologists; however, their

clinical implementation remains constrained by

challenges in interpretability and low acceptance in

routine practice.

Integrating clinical risk factors may enhance

risk stratification for thyroid nodules, as suggested

by a growing body of evidence.21 In alignment

with this, our study incorporated clinical variables

including patient age, sex, number of nodules, and

cervical LN status into the predictive model, thereby

more accurately reflecting routine clinical diagnostic workflows. While previous studies22 23 24 suggested

that male patients with thyroid nodules, particularly

those with indeterminate fine-needle aspiration

cytology undergoing molecular testing, exhibit a

higher malignancy risk,25 our study did not identify

a significant difference in thyroid cancer incidence

between sexes. This discrepancy may be attributable

to methodology differences, as molecular testing was

not performed in our cohort and all diagnoses were

confirmed through postoperative histopathology.

The absence of statistical significance for male sex

may reflect population-specific characteristics,

such as regional variation in risk factor distribution or age composition.26 These methodological and

demographic differences may have attenuated the

observed sex-related effect. Nonetheless, male

patients in our study were assigned higher risk

scores, suggesting an association with malignancy

risk, despite the lack of statistical significance.

Compared with previous models that

primarily focused on intrinsic ultrasound features

of thyroid nodules,27 28 29 our nomogram offers a more

comprehensive assessment. Although the individual

contributions of factors such as sex and age were

relatively modest, they reflected subtle clinical

patterns often considered by radiologists during

decision making. The C-TIRADS optimisation

approach demonstrated clear advantages,

particularly in reducing unnecessary invasive

procedures without compromising diagnostic

accuracy, achieving an AUC of 0.972. Furthermore,

the new model indicated that a risk threshold of

≥60% favoured the recommendation for C-TIRADS

optimisation, whereas a threshold of <30% favoured

exclusion. The integration of complex imaging

data with clinical information represents a core

competency for radiologists.30 With appropriate

standardised training and communication

frameworks in place, radiologists are well positioned

to leverage quantitative metrics generated by the

new model into routine diagnostic workflows. This

advancement holds promise for improving diagnostic

consistency and accuracy in clinical practice.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should

be acknowledged. First, the optimisation of

the TIRADS classification was influenced by

radiologists’ subjective judgement, which may have

contributed to interobserver variability. Second,

although data collection was conducted by trained

junior radiologists, observer variation and the

subjective nature of ultrasound interpretation may

have affected the model’s performance.31 Third,

internal validation using bootstrap resampling may

have overestimated model performance due to

potential overfitting; therefore, external validation

was essential to confirm generalisability. Fourth,

owing to the retrospective design, only a limited

set of clinical parameters (eg, sex, age, and cervical

LN status) was included. Other relevant factors

such as body mass index, environmental exposures,

nodule location, family history of thyroid cancer, and

radiation exposure history,32 33 were not assessed.

Finally, the study cohort exclusively comprised

cases confirmed by surgical pathology, resulting

in a relatively low proportion of benign lesions,

which may have introduced selection bias. The

exclusion of patients diagnosed solely by fine-needle

aspiration was intentional but may have affected the

generalisability of the findings.

Future directions

To address the limitations of the present study, future

research should aim to standardise the application

of TIRADS by adopting unified classification

frameworks and implementing regular training

programmes to enhance interobserver consistency.

Prospective multicentre studies involving broader

and more diverse populations are warranted,

incorporating a wider range of clinical risk factors

to improve predictive accuracy. In particular,

data regarding family history, radiation exposure,

and other relevant variables across centres would

support more comprehensive risk assessment

and enhance the generalisability of prediction

models. In addition, including patients with fine-needle

aspiration–confirmed benign nodules may

help achieve a more balanced representation of

benign and malignant cases. The development and

application of nomogram-based structured training

programmes for radiologists could also be explored

to further improve diagnostic consistency and

clinical utility. While the widespread adoption of a

revised classification system will require time, we

hope that the findings of this study may contribute

to that transition.

Conclusion

We developed and externally validated a nomogram-based

predictive model that integrates imaging

features and clinical risk factors to optimise

C-TIRADS classification for thyroid nodules. The

model demonstrated good discrimination and

calibration across internal and external cohorts,

offering a practical tool to assist radiologists in

refining diagnostic assessments and improving

clinical decision making. Future research

incorporating additional clinical variables and

prospective validation is warranted to further

strengthen the model’s applicability across diverse

clinical settings.

Author contributions

Concept or design: Y Liang, Y Zou, P He, Q Chen.

Acquisition of data: Y Liang, Y Zou, Z Zou, B Ren.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Y Liang, S Peng, Y Zou.

Drafting of the manuscript: Y Liang, Y Zou, HM Yuan, Z Zou.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: P He, Y Zou.

Acquisition of data: Y Liang, Y Zou, Z Zou, B Ren.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Y Liang, S Peng, Y Zou.

Drafting of the manuscript: Y Liang, Y Zou, HM Yuan, Z Zou.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: P He, Y Zou.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This manuscript was initially posted as a preprint entitled ‘Development and validation of a clinical prediction model

to aid radiologists optimize thyroid C-TIRADS classification’

on Research Square (DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3831900/v1).

After peer feedback and extensive revisions undertaken

collaboratively by the author team, the current version has

substantially evolved and markedly differs from the preprint

version.

Funding/support

This research was supported by Sichuan Science and

Technology Program (Ref Nos.:2025ZNSFSC1751,

2026YFHZ0039), the University-Industry Collaborative

Education Program (Ref No.: 250505236300920), the

University-level Project of North Sichuan Medical College

(Ref Nos.: CXSY24-06, CBY22-QNA48), and the Hospital-level

Projects of the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan

Medical College, China (Ref Nos.: 210930, 2023-2GC013,

2025LC010). The funders had no role in the study design, data

collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (Ref No.: ER20210347)

and the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of North

Sichuan Medical College, China (Ref No.: 2021ER436-1). The

requirement for informed patient consent was waived by both

Committees due to the retrospective nature of the research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors, and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American

Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult

patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid

cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task

force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer.

Thyroid 2016;26:1-133. Crossref

2. Zhou J, Song Y, Zhan W, et al. Thyroid imaging reporting

and data system (TIRADS) for ultrasound features of

nodules: multicentric retrospective study in China.

Endocrine 2021;72:157-70. Crossref

3. Trimboli P. Complexity in the interpretation and

application of multiple guidelines for thyroid nodules: the

need for coordinated recommendations for “small” lesions.

Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2025;26:223-7. Crossref

4. Park JY, Lee HJ, Jang HW, et al. A proposal for a thyroid

imaging reporting and data system for ultrasound features

of thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 2009;19:1257-64. Crossref

5. Horvath E, Majlis S, Rossi R, et al. An ultrasonogram reporting system for thyroid nodules stratifying cancer

risk for clinical management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

2009;94:1748-51. Crossref

6. Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG, et al. ACR Thyroid

Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS): white

paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. J Am Coll Radiol

2017;14:587-95. Crossref

7. Shin JH, Baek JH, Chung J, et al. Ultrasonography diagnosis

and imaging-based management of thyroid nodules: revised

Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology consensus statement

and recommendations. Korean J Radiol 2016;17:370-95. Crossref

8. Russ G, Bonnema SJ, Erdogan MF, Durante C, Ngu R,

Leenhardt L. European Thyroid Association guidelines for

ultrasound malignancy risk stratification of thyroid nodules

in adults: the EU-TIRADS. Eur Thyroid J 2017;6:225-37. Crossref

9. Chen Z, Wang JJ, Du JB, et al. Development and validation

of a dynamic nomogram for predicting central lymph node

metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients based

on clinical and ultrasound features. Quant Imaging Med

Surg 2025;15:1555-70. Crossref

10. Boucai L, Zafereo M, Cabanillas ME. Thyroid cancer: a

review. JAMA 2024;331:425-35. Crossref

11. Zhang J, Xu S. High aggressiveness of papillary thyroid

cancer: from clinical evidence to regulatory cellular

networks. Cell Death Discov 2024;10:378. Crossref

12. Ma T, Semsarian CR, Barratt A, et al. Rethinking

low-risk papillary thyroid cancers <1 cm (papillary

microcarcinomas): an evidence review for recalibrating

diagnostic thresholds and/or alternative labels. Thyroid

2021;31:1626-38. Crossref

13. Kwong N, Medici M, Angell TE, et al. The influence of

patient age on thyroid nodule formation, multinodularity,

and thyroid cancer risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

2015;100:4434-40. Crossref

14. Pizzato M, Li M, Vignat J, et al. The epidemiological

landscape of thyroid cancer worldwide: GLOBOCAN

estimates for incidence and mortality rates in 2020. Lancet

Diabetes Endocrinol 2022;10:264-72. Crossref

15. Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG, Hoang JK. Re: ACR

Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS):

white paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. J Am Coll

Radiol 2018;15(3 Pt A):381-2. Crossref

16. Angelopoulos N, Goulis DG, Chrisogonidis I, et al.

Diagnostic performance of European and American

College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data

System classification systems in thyroid nodules over 20

mm in diameter. Endocr Pract 2025;31:72-9. Crossref

17. Jin Z, Pei S, Shen H, et al. Comparative study of C-TIRADS,

ACR-TIRADS, and EU-TIRADS for diagnosis

and management of thyroid nodules. Acad Radiol

2023;30:2181-91. Crossref

18. Wildman-Tobriner B, Buda M, Hoang JK, et al. Using

artificial intelligence to revise ACR TI-RADS risk

stratification of thyroid nodules: diagnostic accuracy and

utility. Radiology 2019;292:112-9. Crossref

19. Wu SH, Li MD, Tong WJ, et al. Adaptive dual-task deep

learning for automated thyroid cancer triaging at screening

US. Radiol Artif Intell 2025;7:e240271. Crossref

20. Trimboli P, Colombo A, Gamarra E, Ruinelli L, Leoncini A.

Performance of computer scientists in the assessment of

thyroid nodules using TIRADS lexicons. J Endocrinol

Invest 2025;48:877-83. Crossref

21. Kobaly K, Kim CS, Mandel SJ. Contemporary management of thyroid nodules. Annu Rev Med 2022;73:517-28. Crossref

22. Xu L, Li G, Wei Q, El-Naggar AK, Sturgis EM. Family

history of cancer and risk of sporadic differentiated thyroid

carcinoma. Cancer 2012;118:1228-35. Crossref

23. Iglesias ML, Schmidt A, Ghuzlan AA, et al. Radiation

exposure and thyroid cancer: a review. Arch Endocrinol

Metab 2017;61:180-7. Crossref

24. Saenko V, Mitsutake N. Radiation-related thyroid cancer.

Endocr Rev 2024;45:1-29. Crossref

25. Figge JJ, Gooding WE, Steward DL, et al. Do ultrasound

patterns and clinical parameters inform the probability of

thyroid cancer predicted by molecular testing in nodules

with indeterminate cytology? Thyroid 2021;31:1673-82. Crossref

26. Li X, Xing M, Tu P, et al. Urinary iodine levels and thyroid

disorder prevalence in the adult population of China: a

large-scale population-based cross-sectional study. Sci Rep

2025;15:14273. Crossref

27. Xiao J, Xiao Q, Cong W, et al. Discriminating malignancy in

thyroid nodules: the nomogram versus the Kwak and ACR

TI-RADS. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;163:1156-65. Crossref

28. Xin Y, Liu F, Shi Y, Yan X, Liu L, Zhu J. A scoring system for assessing the risk of malignant partially cystic thyroid

nodules based on ultrasound features. Front Oncol

2021;11:731779. Crossref

29. Zhou T, Hu T, Ni Z, et al. Comparative analysis of machine

learning-based ultrasound radiomics in predicting

malignancy of partially cystic thyroid nodules. Endocrine

2024;83:118-26. Crossref

30. Bluethgen C, Van Veen D, Zakka C, et al. Best practices

for large language models in radiology. Radiology

2025;315:e240528. Crossref

31. He Z, Li Y, Zeng W, et al. Can a computer-aided mass

diagnosis model based on perceptive features learned from

quantitative mammography radiology reports improve

junior radiologists’ diagnosis performance? An observer

study. Front Oncol 2021;11:773389. Crossref

32. Kim Y, Roh J, Song DE, et al. Risk factors for posttreatment

recurrence in patients with intermediate-risk papillary

thyroid carcinoma. Am J Surg 2020;220:642-7. Crossref

33. Zhao J, Wen J, Wang S, Yao J, Liao L, Dong J. Association

between adipokines and thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis

of case-control studies. BMC Cancer 2020;20:788. Crossref