Universal haemoglobin A1c screening reveals high prevalence of dysglycaemia in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty

Hong Kong Med J 2020 Aug;26(4):304–10 | Epub 7 Aug 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Universal haemoglobin A1c screening reveals

high prevalence of dysglycaemia in patients

undergoing total knee arthroplasty

Vincent WK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; PK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; YC Woo, FRCP (Lond), FHKAM (Medicine)2; Henry Fu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Amy Cheung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; MH Cheung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)3; CH Yan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)3; KY Chiu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)3

1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Vincent WK Chan (drvincentwkchan@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Diabetes mellitus is an established

modifiable risk factor for periprosthetic joint

infection (PJI). Haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a

glycaemic marker that correlates with diabetic

complications and PJI. As diabetes and prediabetes

are frequently asymptomatic, and there is increasing

evidence to suggest a correlation between

dysglycaemia and osteoarthritis, it is reasonable

to provide HbA1c screening before total knee

arthroplasty (TKA). The aim of the present study

was to determine the prevalence of dysglycaemia

in patients who underwent TKA and investigate

whether HbA1c screening and optimisation of

glycaemic control before TKA affects the incidence

of PJI after TKA.

Methods: Patients who underwent primary TKA

before and after routine HbA1c screening was

introduced in our unit were reviewed. Prediabetes

and diabetes were defined according to the American

Diabetes Association. Patients with HbA1c ≥7.5%

were referred to an endocrinologist for optimisation

of glycaemic control before TKA. The incidence PJI,

defined according to the Musculoskeletal Infection

Society criteria, was recorded.

Results: A total of 729 patients (934 knees) had

HbA1c screening before TKA. Of them, 17 (2.3%)

and 184 (25.2%) patients had known prediabetes

and diabetes, respectively, and 265 (36.4%) and 12 (1.6%) had undiagnosed prediabetes and diabetes,

respectively. The incidence of PJI was significantly

lower in all patients who received HbA1c screening

compared with those who did not (0.2% vs 1.02%,

P=0.027).

Conclusion: Screening for HbA1c before TKA

provides a cost-effective opportunity to identify

undiagnosed dysglycaemia. Patients identified as

having dysglycaemia receive modified treatment,

significantly reducing the rate of PJI when compared

with historical controls.

New knowledge added by this study

- There is a high prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in Hong Kong.

- Universal haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) screening before TKA can identify patients with undiagnosed dysglycaemia.

- HbA1c screening should be considered for all patients before TKA.

Introduction

Worldwide, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus

and the number of total knee arthroplasty (TKA)

surgeries performed is increasing; therefore, the

number of patients with dysglycaemia undergoing

TKA is expected to rise.1 2 3 The proportion of patients

undergoing TKA who have diabetes mellitus was

reported to be 20.6% in the US in 2018.4 Diabetes mellitus is associated with various adverse outcomes

after total joint arthroplasty, including periprosthetic

joint infection (PJI).5 6 7 8 9 10 Although the occurrence of

PJI is rare, it is a devastating complication after total

joint arthroplasty, resulting in significant morbidity

and even mortality. The economic burden to manage

PJI after total joint arthroplasty is projected to be

over US$1.62 million by 2020.11 Despite advances in total joint arthroplasty, the risk of PJI remains and

likely cannot be eliminated. Therefore, enhancing

preoperative screening and optimisation of various

risk factors for PJI is of the utmost importance.

Glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a readily

accessible glycaemic control marker and, according

to the American Diabetes Association, HbA1c is

also a predictor for diabetes-related complications.12

Previous studies have found that preoperative

HbA1c >7.5% or 8% is associated with an increased

risk of PJI and wound complications after TKA.13 14 15

Therefore, optimising HbA1c levels to below these

suggested thresholds might be a feasible strategy

to reduce PJI. Moreover, patients with prediabetes

and diabetes are frequently asymptomatic in the

early stages and up to 50% of patients present with

complications at the time of diagnosis.16 Diabetes

mellitus is also associated with the development of

osteoarthritis.17 18 Preoperative assessment for TKA

provides an ideal opportunity for diabetes screening.

In our centre, we introduced universal HbA1c

screening 2 to 3 months before surgery for all patients

undergoing TKA, regardless of their diabetic status,

in March 2017. Patients with HbA1c level ≥7.5%

are referred to an endocrinologist for optimisation

of glycaemic control before proceeding to TKA

surgery.

The aim of the present study was to determine

the prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes in patients

who underwent TKA and investigate whether the

introduction of universal HbA1c screening and

optimisation of glycaemic control affected the rate

of PJI after TKA.

Methods

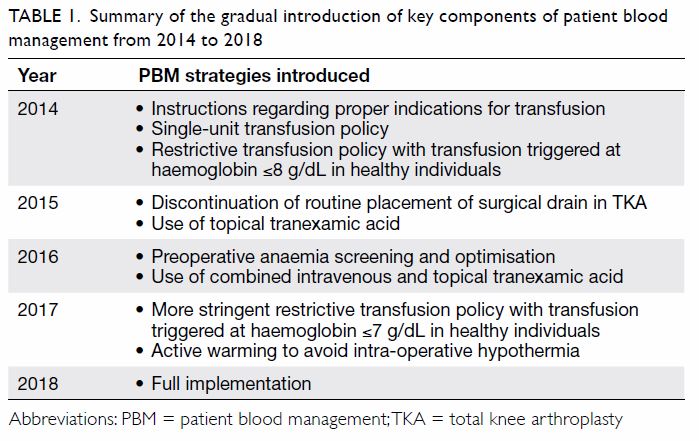

All patients who underwent primary TKA at Queen

Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, from December 2014 to

May 2019 were reviewed. Patients were diagnosed as

prediabetes or diabetes according to the American

Diabetes Association definitions, wherein a HbA1c

level of 5.7% to 6.4% is defined as prediabetes,

and a HbA1c level ≥6.5% is defined as diabetes.10

Patients were classified as undiagnosed prediabetes

or diabetes if there was no previous diagnosis or

diabetic status in the patient’s medical record.

Patients with HbA1c level ≥7.5% were referred to

an endocrinologist for optimisation of glycaemic

control before proceeding to TKA.

Patients who underwent primary TKA from

December 2014 to February 2017 did not receive

universal HbA1c screening. These patients were

included in the study as historical controls, to

compare the PJI rate with patients who received

HbA1c screening before undergoing TKA from

March 2017 to May 2019. These 27-month periods

immediately prior to and after the initiation of

HbA1c screening were chosen to match as closely

as possible the duration, comparable indications,

perioperative management, surgical technique, and

wound care protocol for better comparisons.

All patients received one dose of prophylactic

antibiotic on the induction of anaesthesia and no

further doses of antibiotics postoperatively. All

PJIs were defined according to the Workgroup of

the Musculoskeletal Infection Society diagnostic

criteria.19

The primary outcome of this study was

the prevalence of undiagnosed prediabetes and

diabetes in patients undergoing TKA, identified by

universal HbA1c screening. The secondary outcome

was the difference in the PJI rate between patients

undergoing TKA who received HbA1 screening and

historical control patients undergoing TKA who did

not receive HbA1c screening.

Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical

analysis of categorical variables, and Student’s t test

was used for continuous variables. We used SPSS

(Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

US) for all analyses. A P value <0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

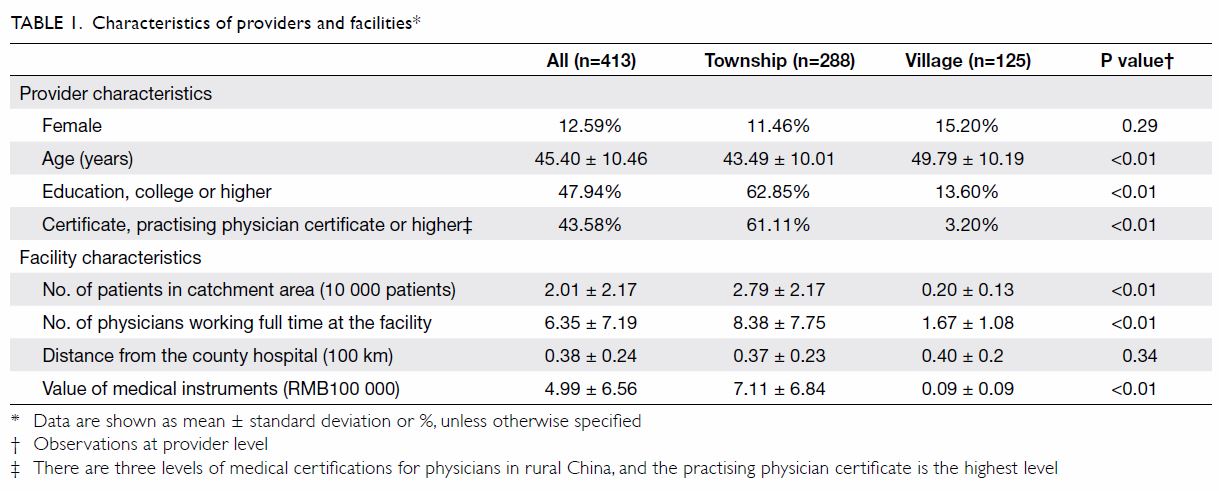

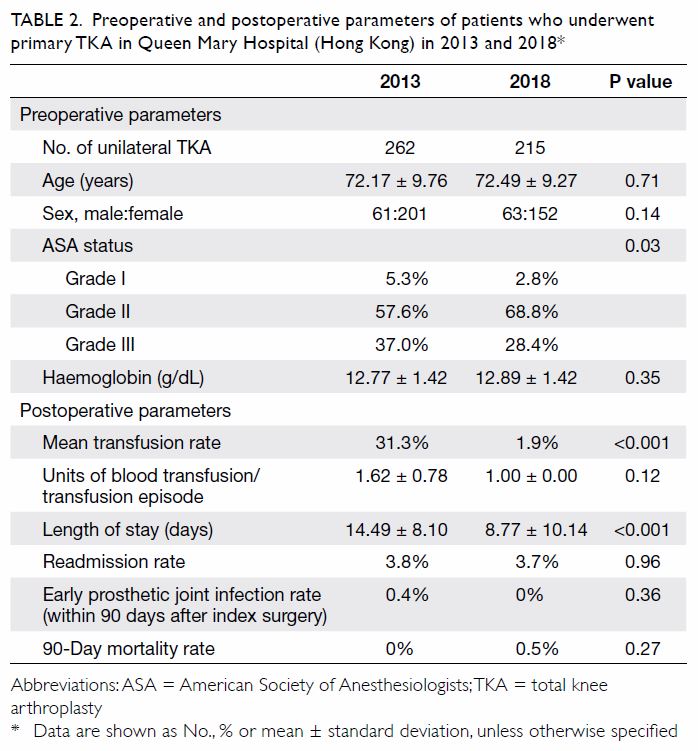

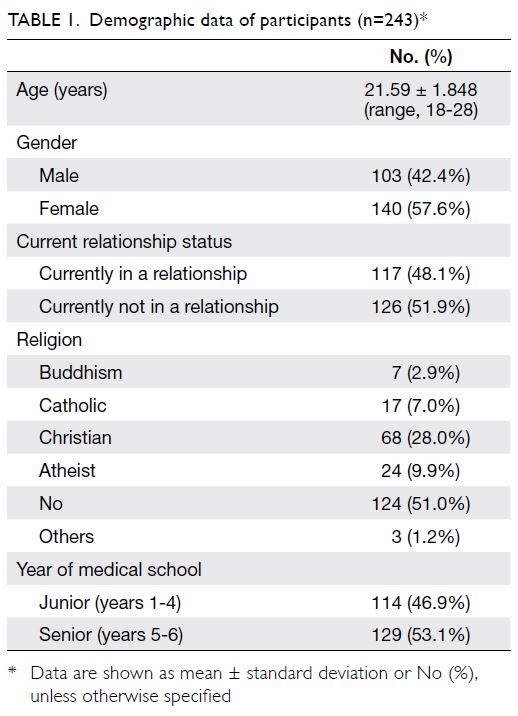

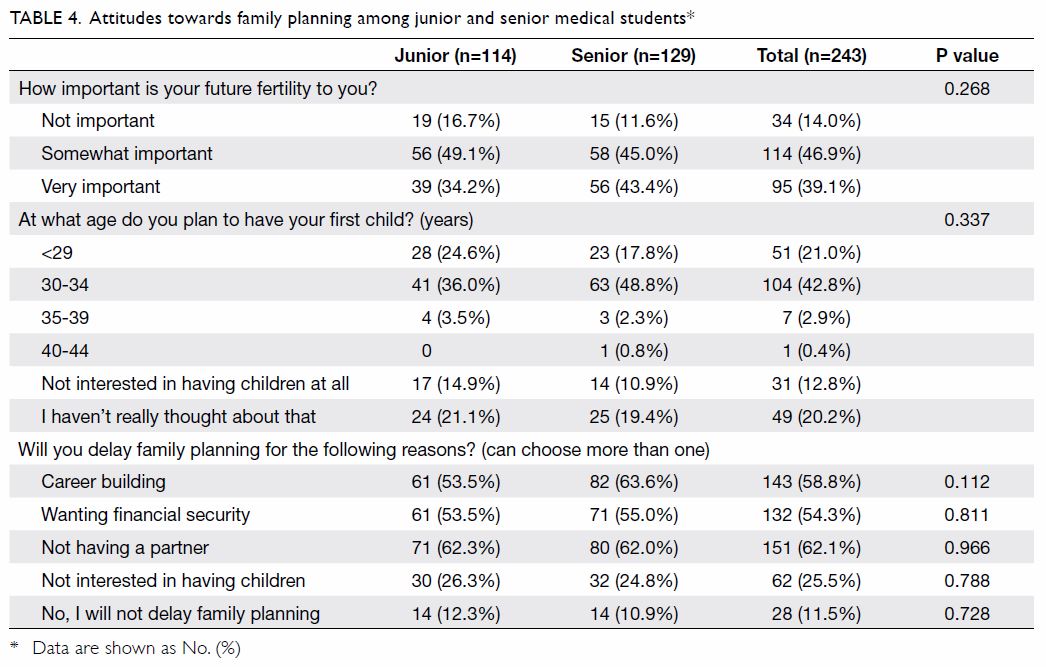

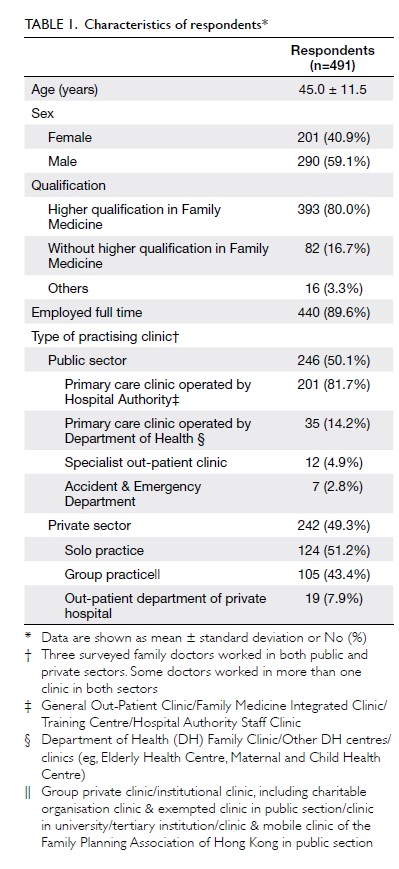

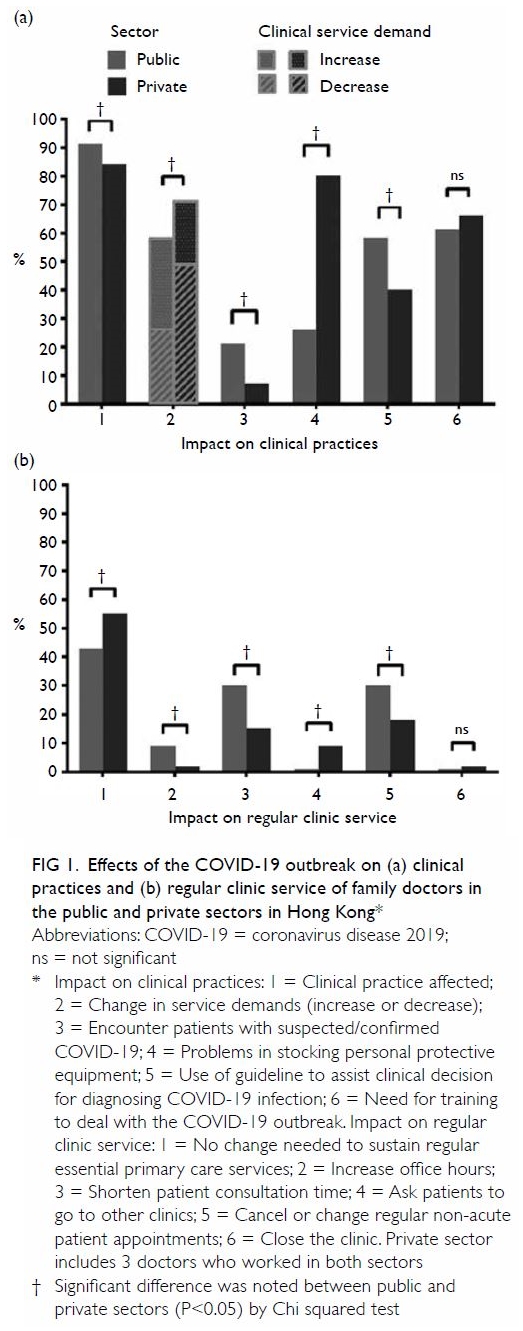

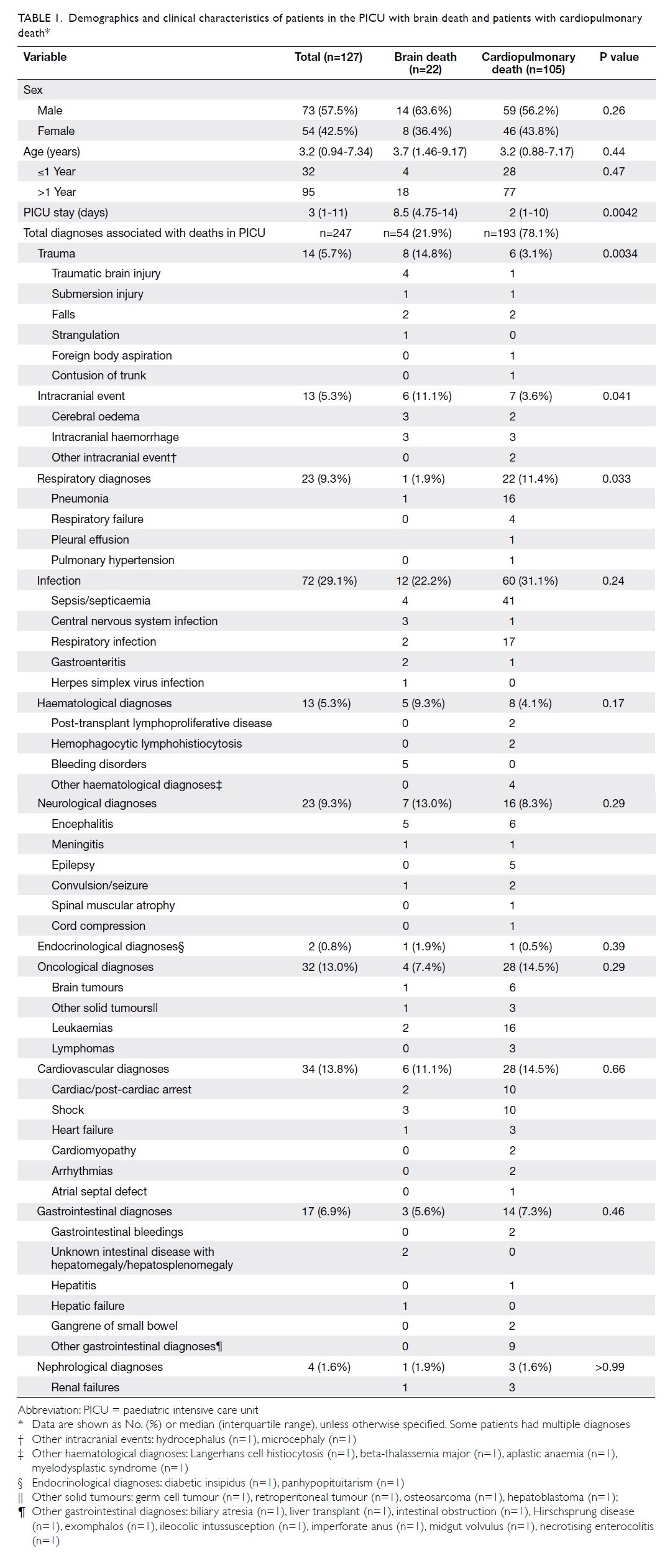

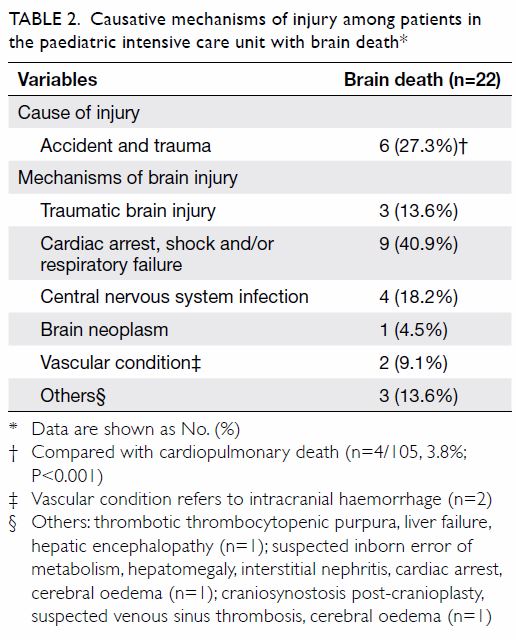

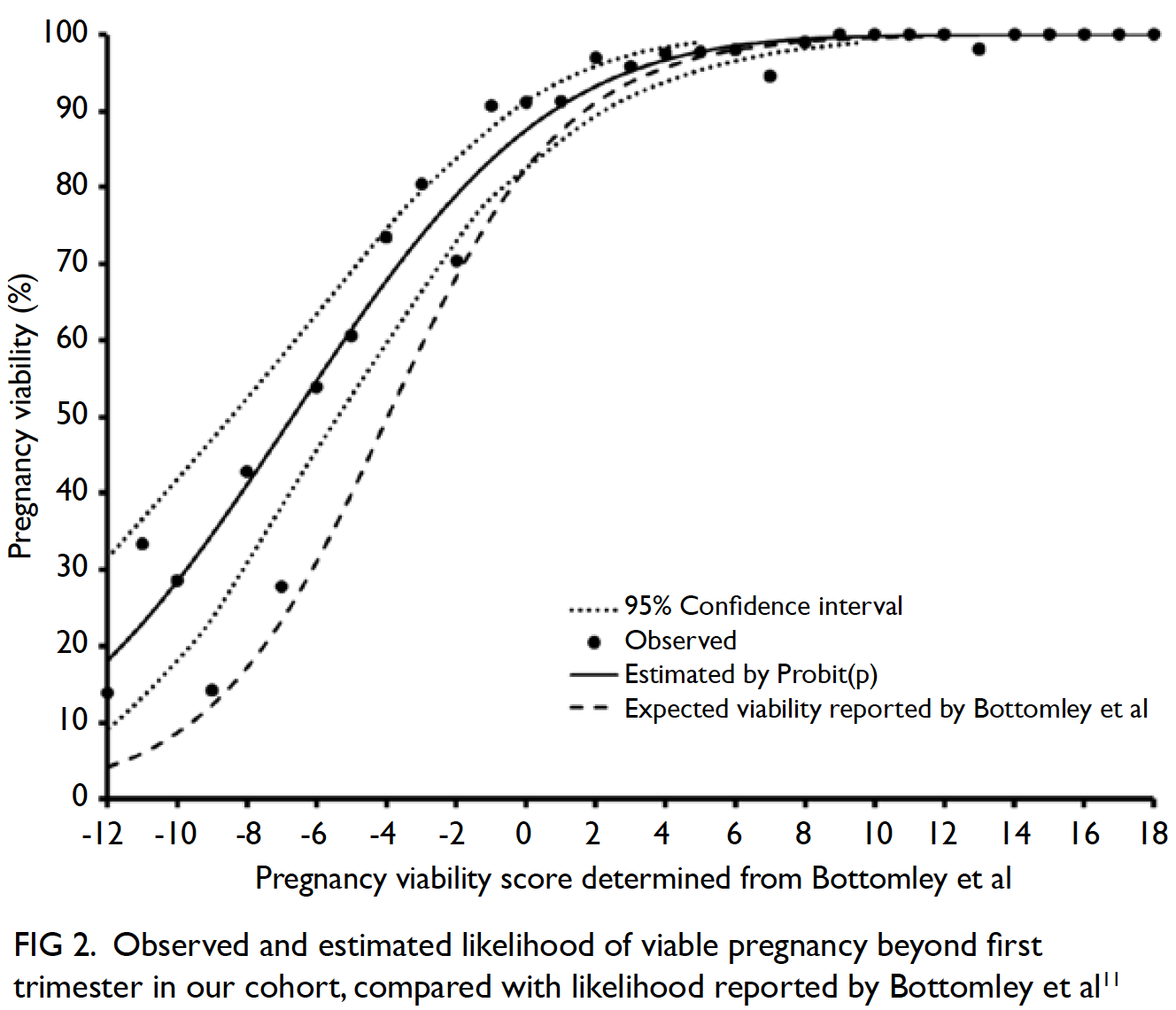

A total of 1566 patients (2017 knees) who underwent

primary TKA were included for analysis. Of them, 729 patients (934 knees) received HbA1c screening

before TKA surgery and 837 patients (1083 knees) did

not. The baseline demographics for both groups of

patients, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI),

the prevalence of known diabetes and diagnosis

for TKA are shown in Table 1. The BMI of patients

who received HbA1c screening was significantly

higher than that of patients who did not (28.4±4.7 vs

27.1±4.5, P=0.0001). Other baseline characteristics

were not significantly different between the

two groups.

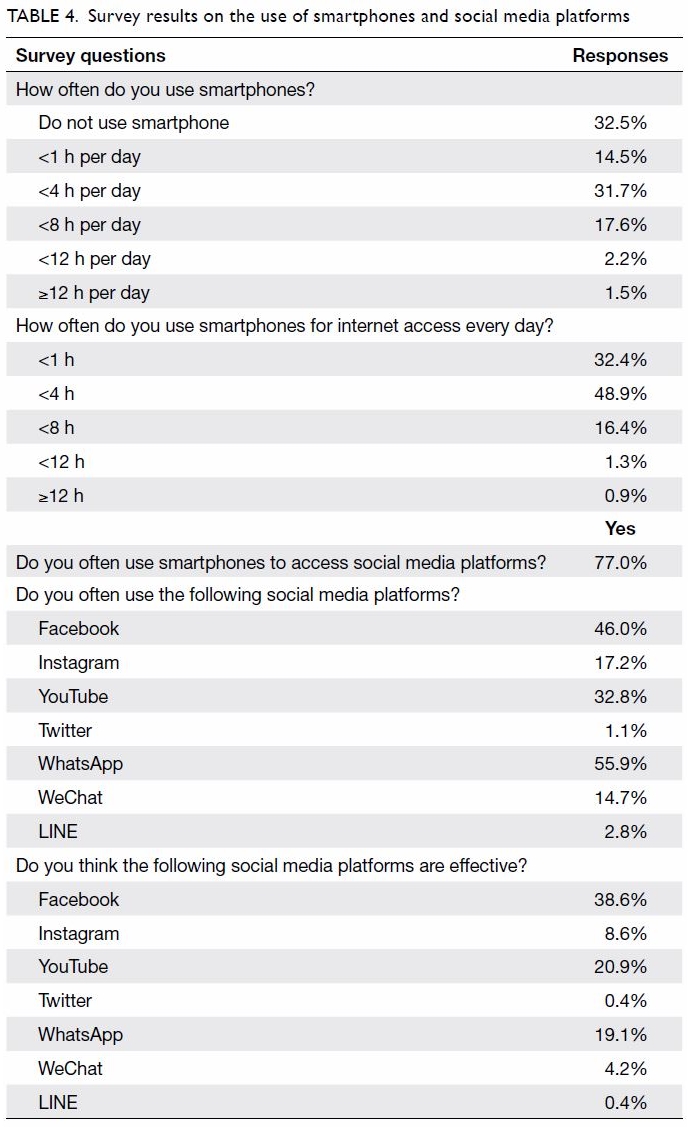

Table 1. Demographics of patients who received HbA1c screening and optimisation of glycaemic control before undergoing TKA, and patients who underwent TKA without screening

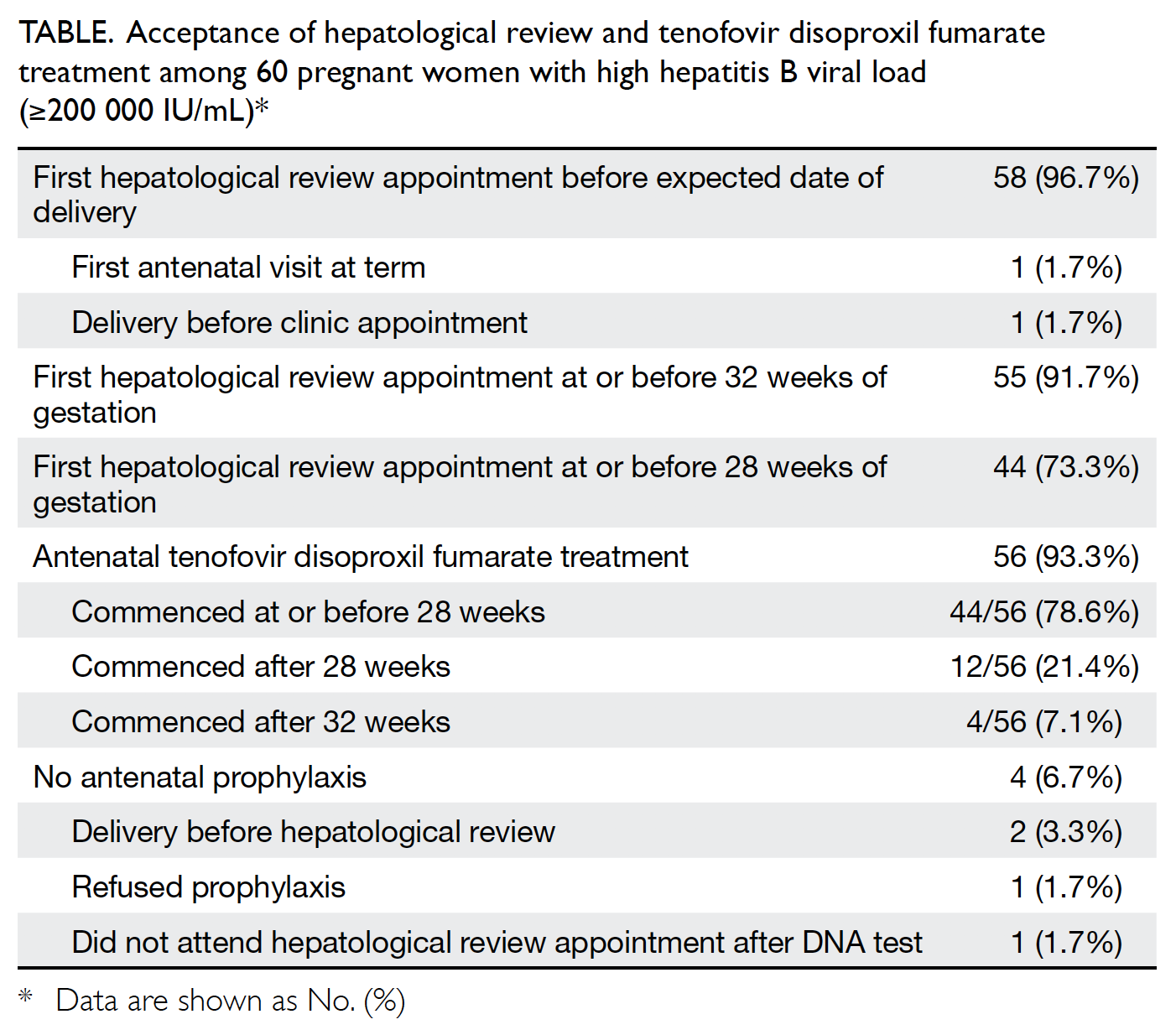

Of the patients who received HbA1c screening,

17 (2.3%) patients were referred to an endocrinologist

for optimisation of glycaemic control before TKA

and all 17 were seen within 4 months. All 17 of these

patients had TKA performed 3 to 18 months after

HbA1c level was controlled to <7.5%.

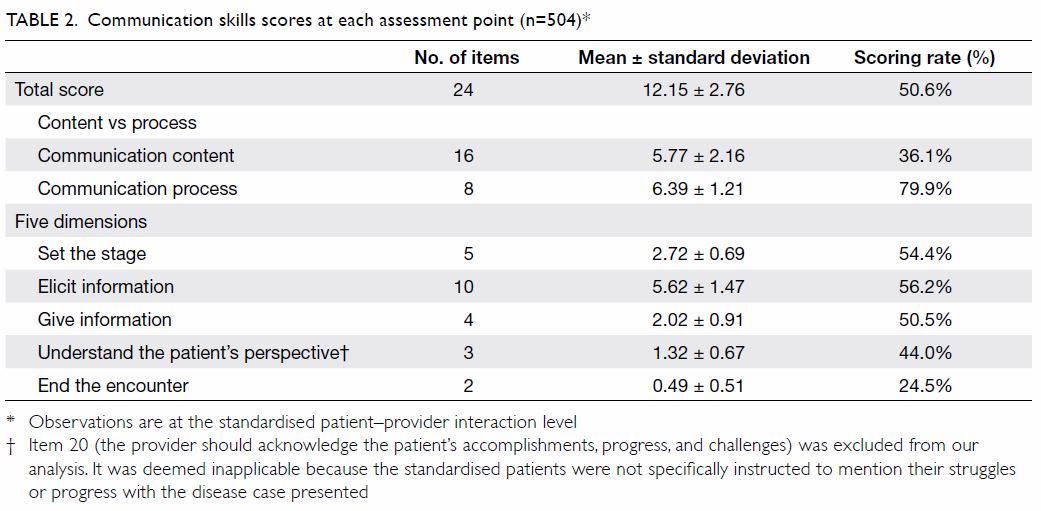

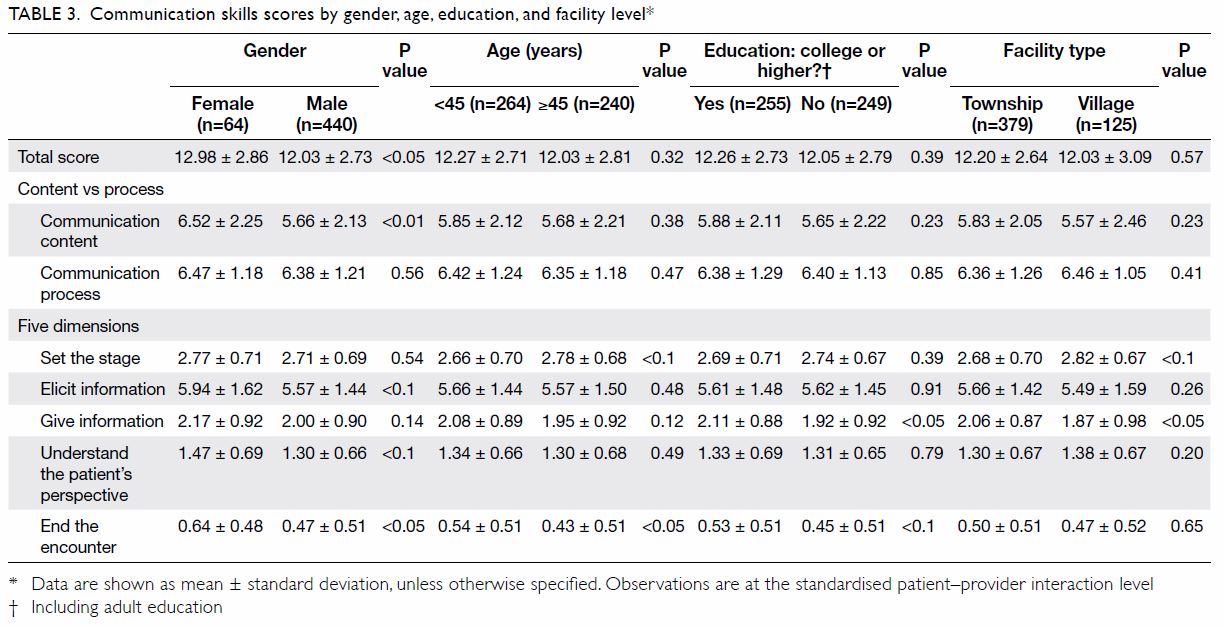

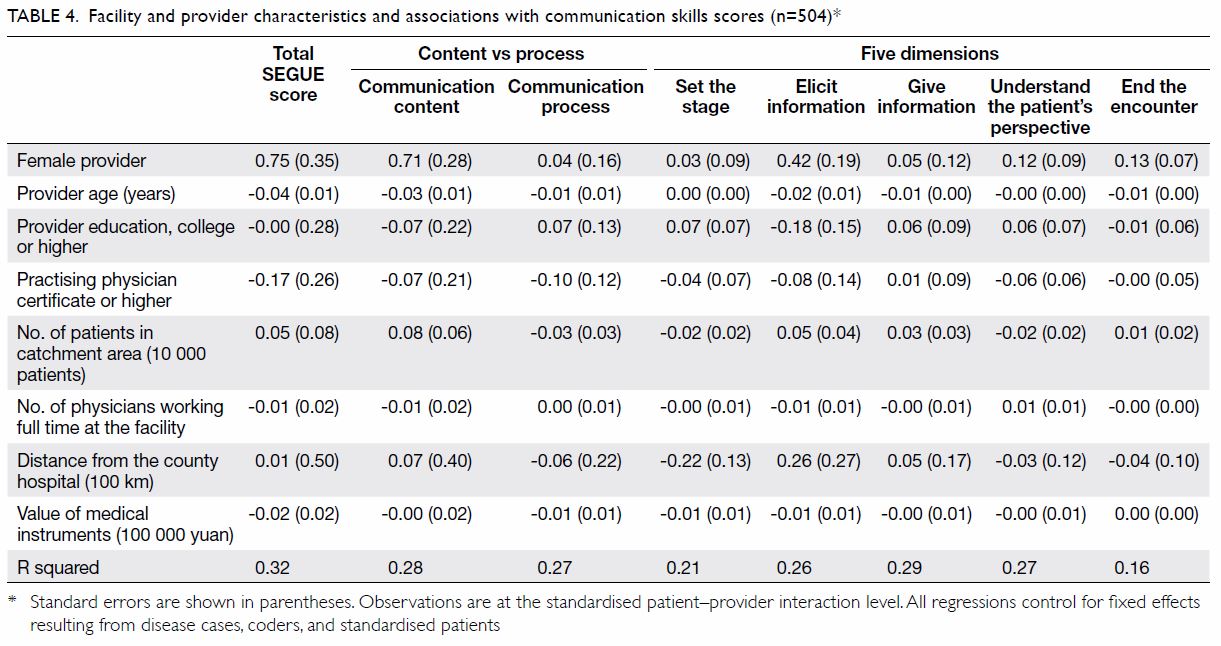

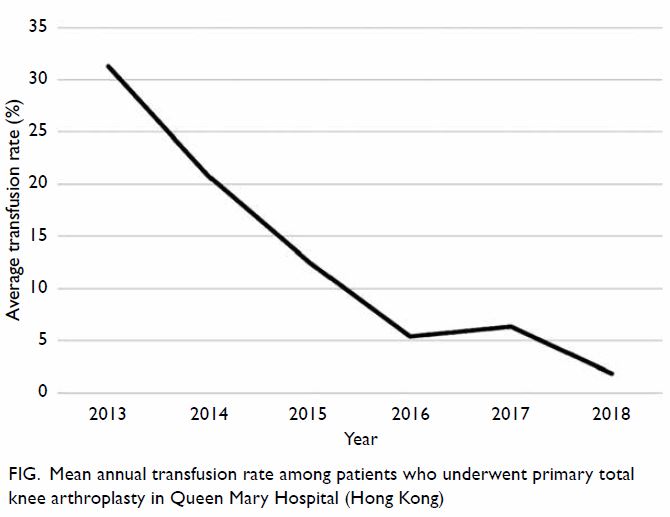

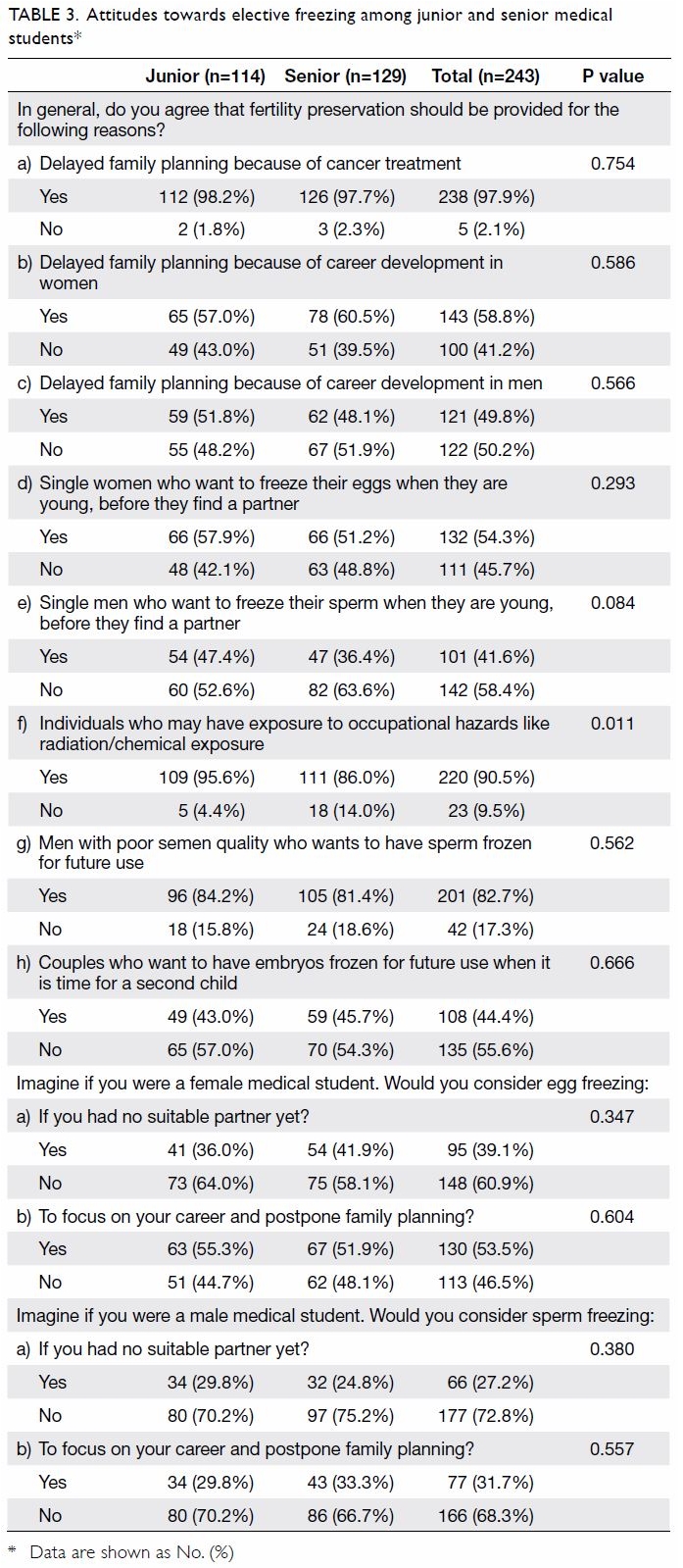

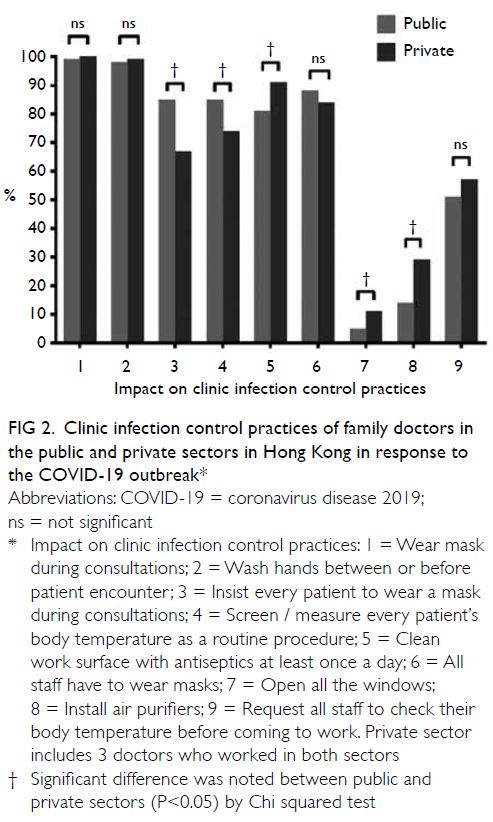

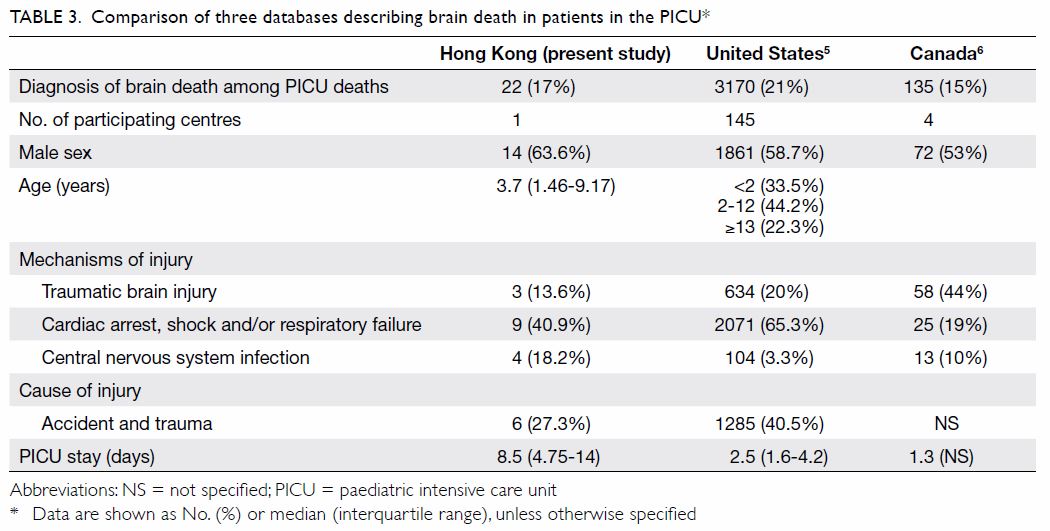

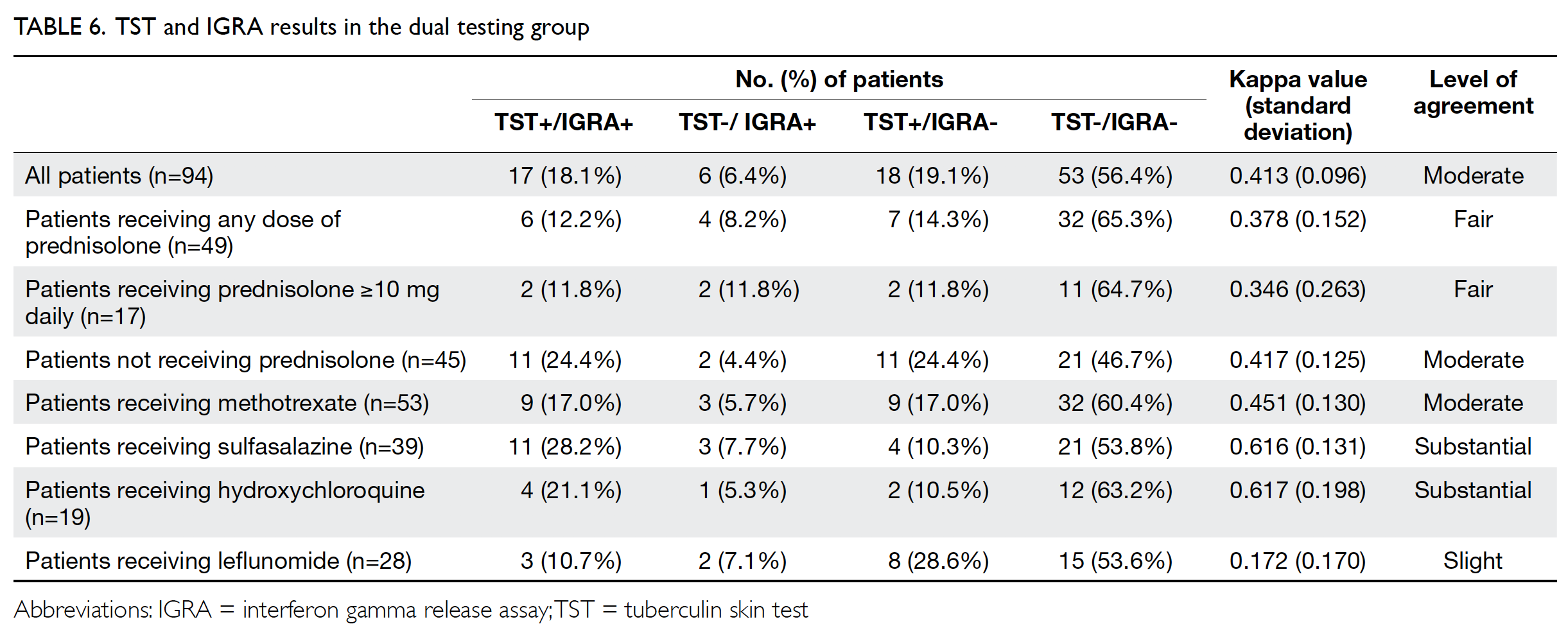

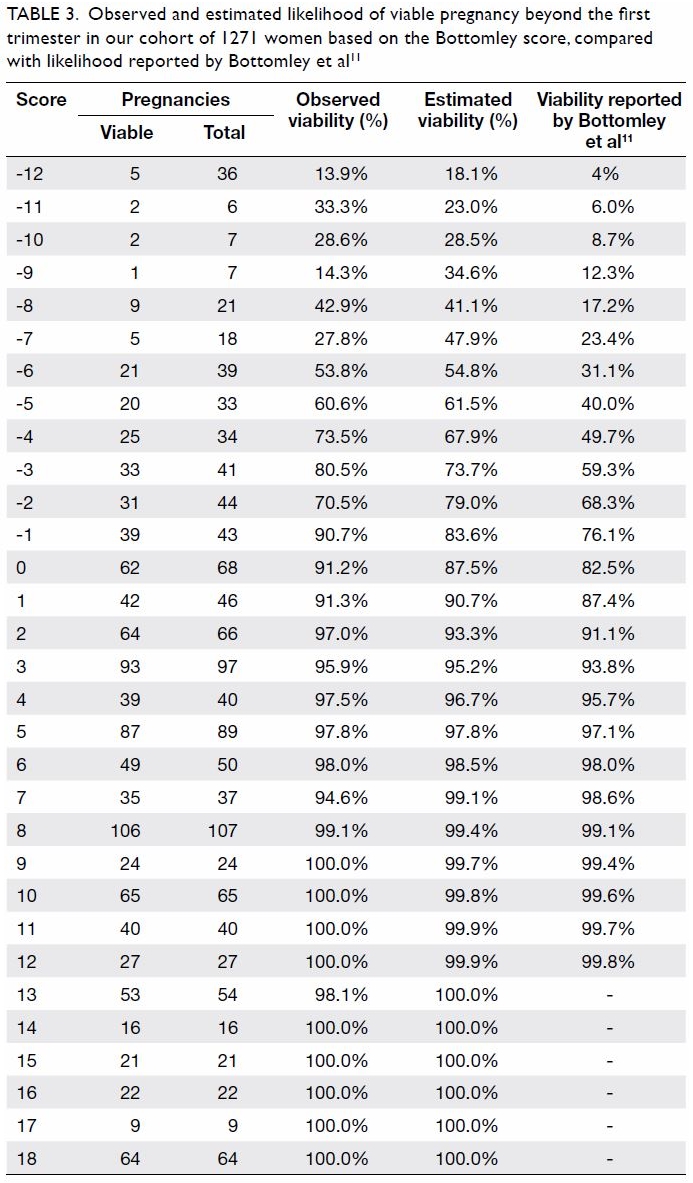

Concerning the results for universal HbA1c

screening, the overall prevalence of diabetes and

prediabetes was 26.9% and 38.7%, respectively.

Patients with a known diagnosis of diabetes and

prediabetes consisted of 25.2% and 2.3%, respectively,

while undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes

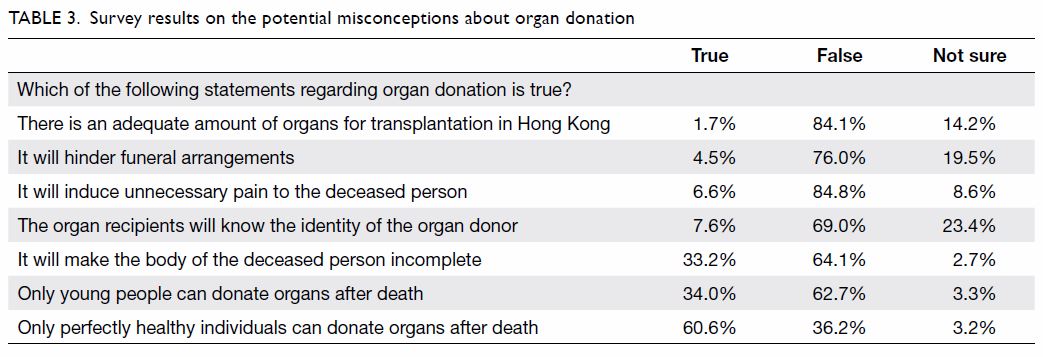

consisted of 1.6% and 36.4% as shown in Table 2.

Therefore, a total of 38% of patients scheduled for

primary TKA have undiagnosed dysglycaemia that

were only detected with HbA1c screening. Mean

(±standard deviation) HbA1c levels for patients with

undiagnosed diabetes, undiagnosed prediabetes,

known diabetes, known prediabetes, and those

without diabetes were 6.7%±0.15 (range, 6.5-7%),

5.9%±0.20 (range, 5.7-6.4%), 6.6%±0.62 (range,

4.6-8.6%), 6.1%±0.45 (range, 5.4-6.4%), and

5.4%±0.19 (range, 4.8-5.6%), respectively, as shown

in Table 2.

Table 2. Prevalence of diabetes status and HbA1c% of patients who had universal HbA1c screening before total knee arthroplasty (n=729)

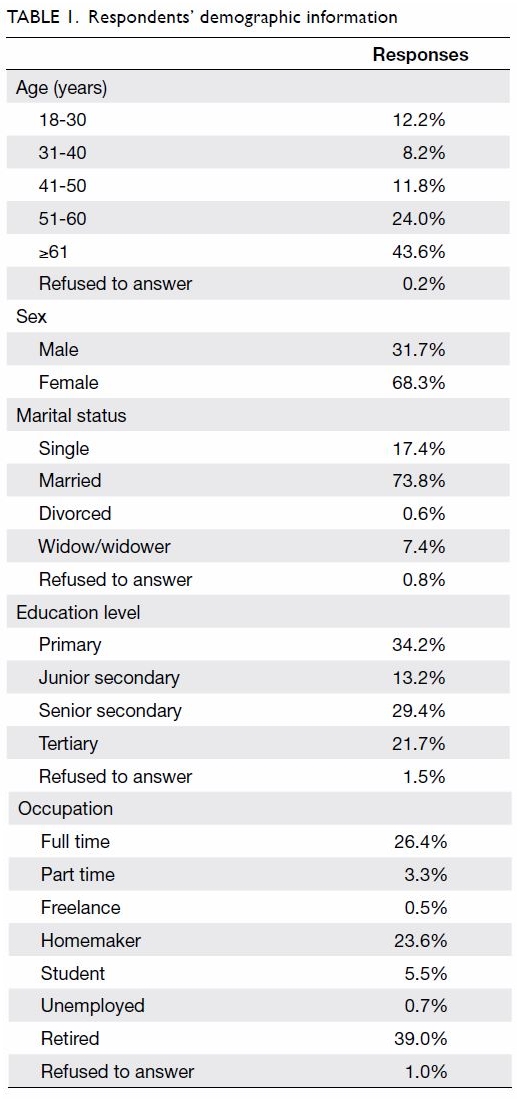

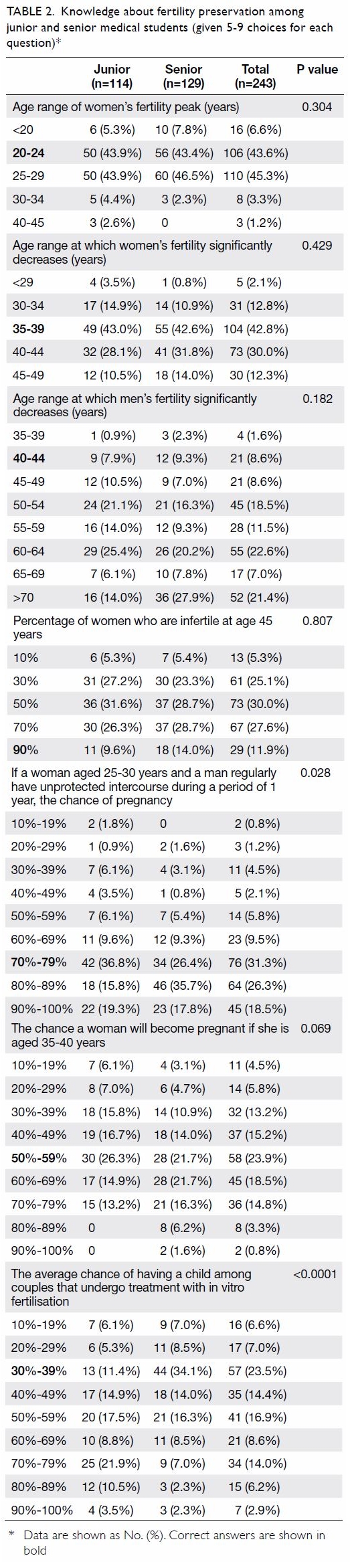

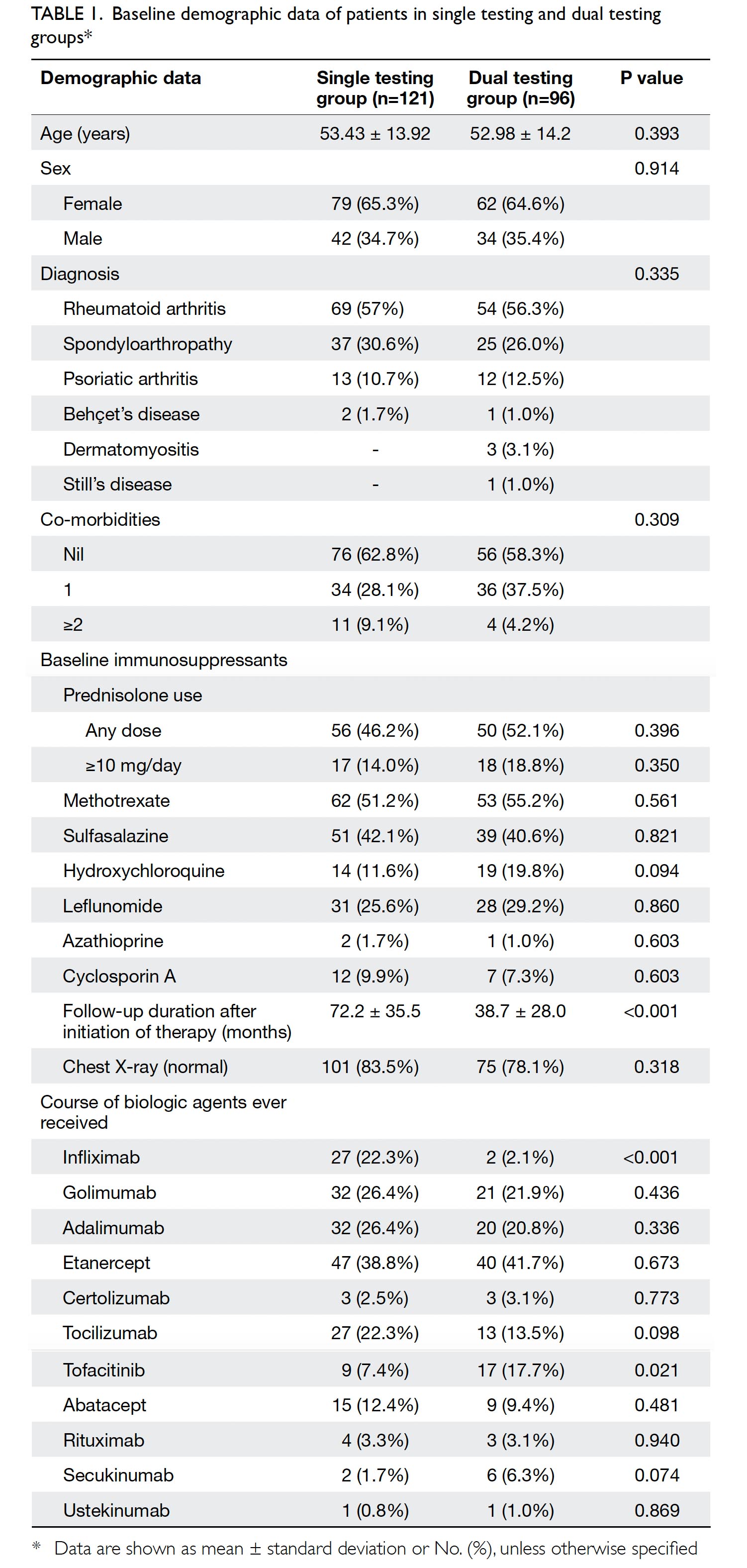

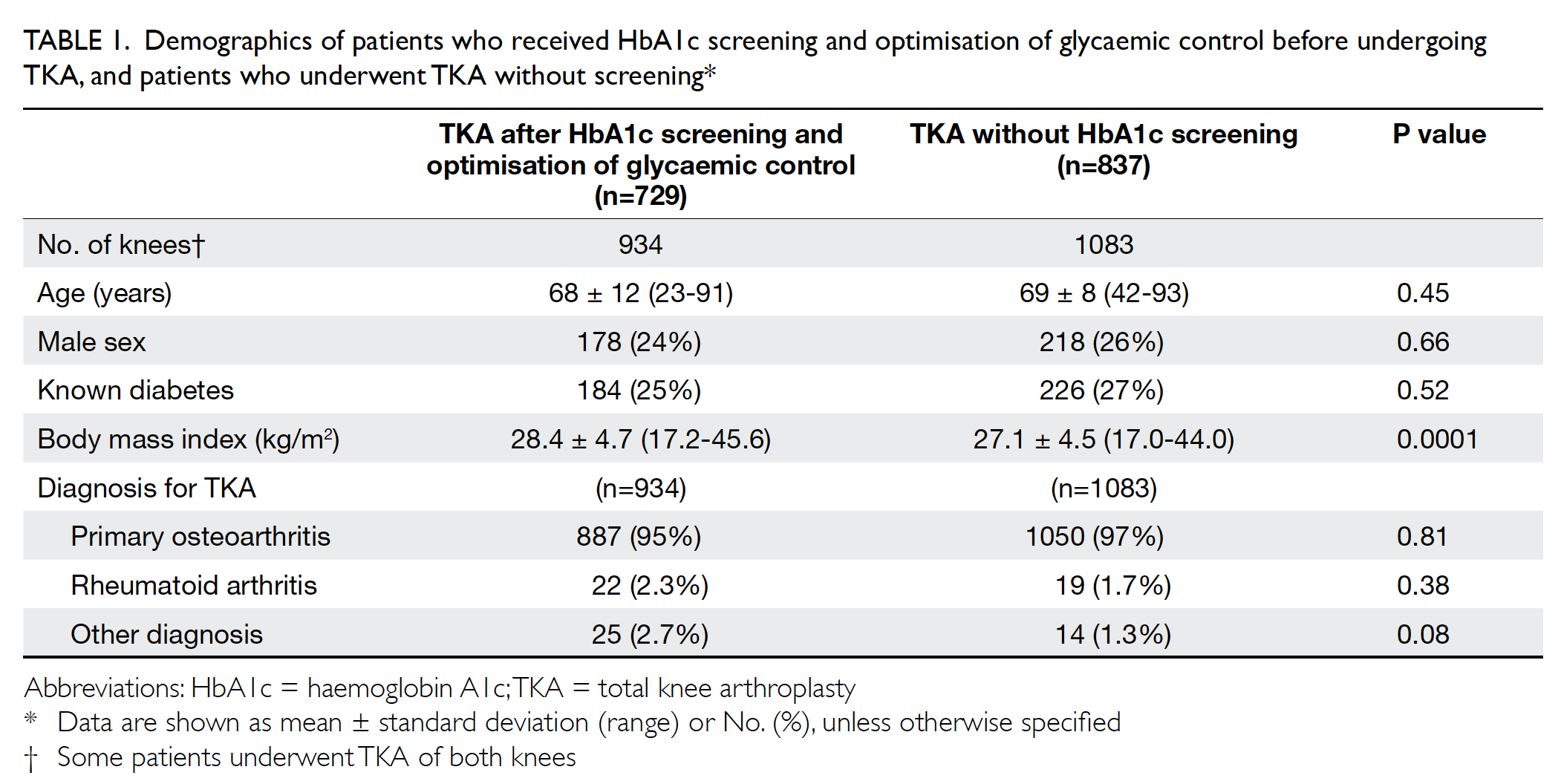

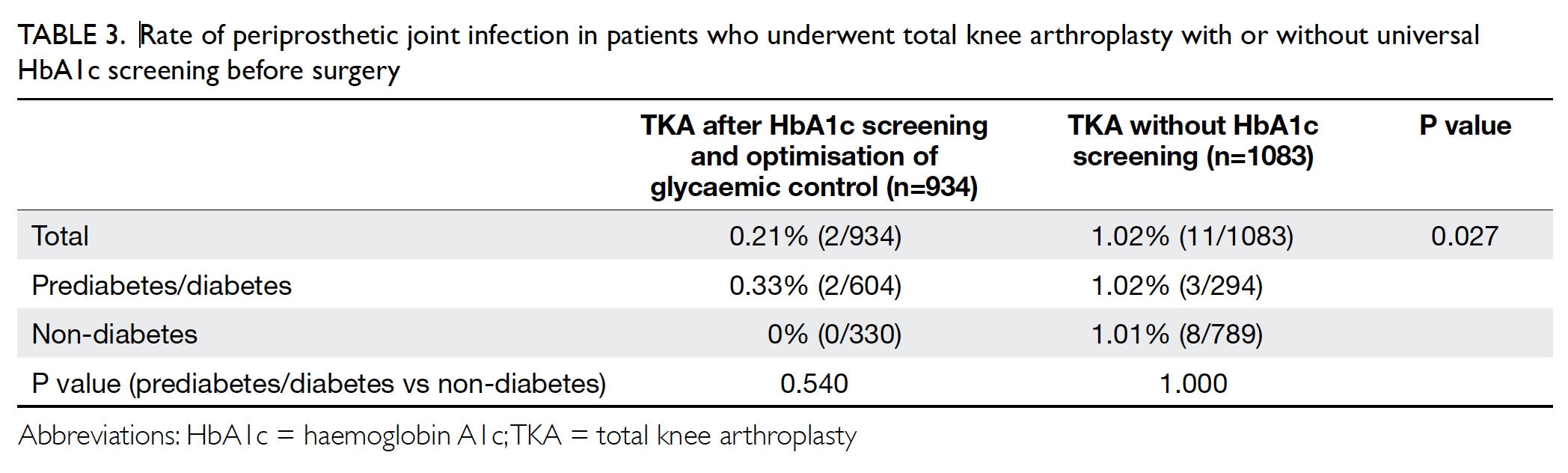

The PJI rate for patients who received HbA1c

screening before undergoing TKA was significantly lower than that for the historical control group

(0.2% vs 1.0%; P=0.027) [Table 3]. Further

comparisons found that the PJI rate for patients with

dysglycaemia was not significantly higher than that

for patients without dysglycaemia in the HbA1c

screening group (0.33% vs 0%; P>0.05). The rate of

PJI was not significantly different between patients

with and without diabetes in the historical control

group (1.03% vs 1.02%; P>0.05).

Table 3. Rate of periprosthetic joint infection in patients who underwent total knee arthroplasty with or without universal HbA1c screening before surgery

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that a

substantial proportion (38.0%) of patients undergoing

primary TKA had undiagnosed prediabetes or

diabetes. This finding is consistent with an earlier

study in the US, which reported 33.6% of patients had

undiagnosed dysglycaemia before total hip or knee

arthroplasty.20 Universal HbA1c screening allows for earlier diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes

and timely intervention. Because diabetes mellitus

is an established risk factor for PJI,5 6 7 8 9 identifying

patients with prediabetes and diabetes allows better

preoperative communication and risk expectation

with the patient before surgery. Moreover, initiating

medical treatment to optimise blood glucose control

may reduce postoperative hyperglycaemia, of clinical

significance, which is an independent risk factor for

wound complications and PJI.21 22 23

Undiagnosed prediabetes was found in 36.4%

of our TKA patients. These patients might have

remained undiagnosed for a long period, as most

were asymptomatic. Nathan et al24 reviewed the

natural history of prediabetes and found that 25%

of patients with prediabetes progress to diabetes

over the subsequent 3 to 5 years. Therefore, early

detection and treatment of prediabetes is important

to prevent the development of diabetes and its

complications. Early lifestyle changes and medical

treatment for prediabetes reduce the chance of

progressing to diabetes.25 26

In the present study, the PJI rate for patients

who received HbA1c screening before undergoing

TKA was significantly lower than that for the

historical control group (0.2% vs 1.0%; P=0.027).

However, only 17 (2.3%) of the screened patients

required endocrinologist referral; therefore, the

observed reduction in PJI is likely the result of

multiple factors. Antibiotic-loaded cement can

reduce PJI after total joint arthroplasty27 28; therefore,

we routinely use antibiotic-loaded cement for

patients with dysglycaemia, who are considered

at higher risk of PJI. Further measures are used to

prevent postoperative hyperglycaemia in patients

with dysglycaemia, such as closer monitoring

of glucose level, choice of intravenous fluid, and

providing a diabetic diet during their in-patient

stay. In addition to screening for dysglycaemia and

direct optimisation of glycaemic control, employing

a more preventive perioperative care might have

contributed to the observed lower rate of PJI in all

patients who received HbA1c screening.

Patients with diabetes and prediabetes are at increased risk of transient hyperglycaemia and

increase glycaemic variability.29 30 Acute glucose

fluctuation increases oxidative stress at the

cellular level increasing diabetic microvascular

and macrovascular complications.29 31 32 Moreover,

a recent retrospective review using point-of-care

glucose measurement showed that higher

postoperative glucose variability after total joint

arthroplasty is associated with adverse outcomes,

including surgical site infection and PJI.33 Therefore,

identifying patients with prediabetes and diabetes

before surgery allows closer postoperative

surveillance and glycaemic control, which might

improve the patients’ clinical outcomes.

Universal HbA1c screening for diabetes

among patients undergoing primary TKA fulfils

many of the criteria for effective screening set out

by Wilson and Jungner34 in 1968, including being

an important and prevalent health issue, having an

acceptable screening test and treatment, and having

a recognised early asymptomatic stage. Quan et al3

reviewed the complete census of public health

records in Hong Kong and reported that the overall

incidences of diabetes and prediabetes in 2014

were 10.29% and 8.9%, respectively. In the present

study, we found that the prevalences of diabetes and

prediabetes in Hong Kong patients undergoing TKA

were 26.9% and 38.7% respectively, which are much

higher than in the general local population. This

is explained by the linkage between diabetes and

osteoarthritis, together with the relatively older age

of patients undergoing TKA.17 18 Moreover, the mean

BMI in both patient groups is above the cut-off value

for obesity in the Hong Kong Chinese population,35

and these patients are therefore considered at high

risk for developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular

disease by the World Health Organization.36 Thus,

preoperative assessment for TKA provides an ideal

occasion for opportunistic screening for diabetes.

Blood HbA1c level is a useful marker in

monitoring glucose control and correlates with

diabetic complications.12 37 Multiple studies have

shown that high preoperative HbA1c is associated

with PJI and wound complications after TKA, with proposed HbA1c thresholds from 7.5% to 8%.13 14 15

Other glycaemic markers, such as preoperative

fasting glucose, fructosamine, postoperative

hyperglycaemia, and glucose variability, are also

associated with an increased risk of adverse clinical

outcomes, including PJI.21 22 23 31 38 Future studies are

needed to clarify the role of each marker, and the use

of continuous glucose monitoring devices can reveal

the postoperative glucose profile in patients with

and without diabetes mellitus after TKA.

The rate of PJI after total joint arthroplasty

is 0.5% to 2%, and PJI remains the leading cause

of revision arthroplasty, comprising up to 25%

of all TKA failures.39 40 41 42 Preventing PJI will have a

substantial impact on clinical outcomes and the

economic burden on our healthcare system. The

cost of a single HbA1c test in local laboratories

ranges from HK$290 to HK$480. We found that

38% of patients scheduled for primary TKA had

undiagnosed dysglycaemia. Therefore, the cost to

identify each case of undiagnosed dysglycaemia

would be HK$870 to HK$1440, and these patients

can receive appropriate and timely treatment. In

contrast, treating a single PJI would cost HK$530 000

to HK$830 000.43 Using 7.5% as the HbA1c threshold

for referral, we found that only 2.3% of the screening

population required assessment and optimisation

of glycaemic control by an endocrinologist. Hence,

our HbA1c screening and optimisation of glycaemic

control did not result in excessive use of medical

services.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the

first study to compare the PJI rate of patients who

underwent TKA with or without preoperative

universal HbA1c screening. Our findings from a

Hong Kong Chinese population add to the body of

evidence supporting universal HbA1c screening for

patients undergoing TKA. Although few patients

in the present study required endocrinologist

assessment, identifying undiagnosed dysglycaemia

allows early and appropriate intervention. Knowing

the diabetic status of patients undergoing TKA also

alters the perioperative treatment of these patients,

including the use of antibiotic-loaded cement,

the choice of intravenous fluid, and postoperative

glucose monitoring. Because primary TKA is an

elective surgery, the risk factors for adverse outcomes

should be thoroughly assessed and optimised, to

improve patient safety and maximise the benefit of

the surgery.

There are several limitations to this study.

This was a retrospective study involving Hong

Kong Chinese patients undergoing TKA at a single

institution. Genetic and social differences affect the

prevalence of diabetes,44 and the perioperative care

for dysglycaemic patients varies between different

institutions; therefore caution is advised when

generalising the results to other populations. Other medical co-morbidities that affect the risk of PJI were

not controlled for, such as rheumatological diseases,

obesity, malnutrition, preoperative anaemia, history

of steroid administration, and malignancy.7 45 46 In the

present study, diagnosis and identification of PJI was

based on analysis of medical records in the public

healthcare system. Patients treated elsewhere, such

as in the private healthcare sector, were not included

in this study. Similarly, patients in the historical

control that had dysglycaemia diagnosed and

managed by private practitioners would be labelled as

non-diabetes. Moreover, diabetes and prediabetes

were defined using only HbA1c, and fasting blood

glucose and oral glucose tolerance tests were not

performed, potentially leading to an underestimation

of dysglycaemia. Finally, although all TKA procedures

and perioperative care routines were performed

consistently by the same surgical team, advances in

surgical technique and perioperative patient care

may have created bias when historical data are used

as controls. Future prospective, comparative studies

with larger sample sizes and multivariate analyses

are required to clarify the role of universal diabetes

screening and optimisation of the risks of PJI after

total joint arthroplasty.

Conclusion

Universal HbA1c screening for patients before

undergoing TKA provides a valuable opportunity

to identify undiagnosed dysglycaemia. Patients

identified as having dysglycaemia receive modified

treatments, including preoperative optimisation of

glycaemic control, resulted in a significantly lower

rate of PJI when compared with historical controls.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of the study, analysis

or interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and

critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to

the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

The results of this study were presented in part as a free paper on adult joint reconstruction at the Hong Kong Orthopaedic

Association Annual Congress in 2019.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster Institutional Review Board (Ref UW 20-157). The need for informed

consent from the patients was waived by Institutional Review

Board, owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

References

1. Klonoff DC. The increasing incidence of diabetes in the

21st century. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2009;3:1-2. Crossref

2. Memtsoudis SG, Della Valle AG, Besculides MC, Gaber L,

Laskin R. Trends in demographics, comorbidity profiles,

in-hospital complications and mortality associated with

primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009;24:518-27. Crossref

3. Quan J, Li TK, Pang H, et al. Diabetes incidence and

prevalence in Hong Kong, China during 2006-2014. Diabet

Med 2017;34:902-8. Crossref

4. Shohat N, Goswami K, Tarabichi M, Sterbis E, Tan TL,

Parvizi J. All patients should be screened for diabetes before

total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:2057-61. Crossref

5. Marchant MH Jr, Viens NA, Cook C, Vail TP, Bolognesi MP.

The impact of glycemic control and diabetes mellitus on

perioperative outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J

Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1621-9. Crossref

6. Stryker LS, Abdel MP, Morrey ME, Morrow MM, Kor DJ,

Morrey BF. Elevated postoperative blood glucose and

preoperative hemoglobin A1C are associated with

increased wound complications following total joint

arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:808-14, S1-2. Crossref

7. Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD;

INFORM Team. Patient-related risk factors for

periprosthetic joint infection after total joint arthroplasty:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One

2016;11:e0150866. Crossref

8. Bozic KJ, Lau E, Kurtz S, et al. Patient-related risk factors

for periprosthetic joint infection and postoperative

mortality following total hip arthroplasty in Medicare

patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:794-800. Crossref

9. Schwarz EM, Parvizi J, Gehrke T, et al. 2018 International

Consensus Meeting on Musculoskeletal Infection:

Research Priorities from the General Assembly Questions.

J Orthop Res 2019;37:997-1006. Crossref

10. Meding JB, Reddleman K, Keating ME, et al. Total knee

replacement in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin

Orthop Relat Res 2003;(416):208-16. Crossref

11. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J.

Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the

United States. J Arthroplasty 2012;27(8 Suppl):61-5.e1. Crossref

12. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care

in diabetes–2013. Diabetes Care 2013;36 Suppl 1:S11-66. Crossref

13. Cancienne JM, Werner BC, Browne JA. Is there an

association between hemoglobin A1C and deep

postoperative infection after TKA? Clin Orthop Relat Res

2017;475:1642-9. Crossref

14. Tarabichi M, Shohat N, Kheir MM, et al. Determining the

threshold for HbA1c as a predictor for adverse outcomes

after total joint arthroplasty: a multicenter, retrospective

study. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:S263-S267.e1. Crossref

15. Han HS, Kang SB. Relations between long-term glycemic

control and postoperative wound and infectious

complications after total knee arthroplasty in type 2

diabetics. Clin Orthop Surg 2013;5:118-23. Crossref

16. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). VIII. Study

design, progress and performance [editorial]. Diabetologia

1991;34:877-90. Crossref

17. Courties A, Sellam J. Osteoarthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus: What are the links? Diabetes Res Clin Pract

2016;122:198-206. Crossref

18. Schett G, Kleyer A, Perricone C, et al. Diabetes is

an independent predictor for severe osteoarthritis:

results from a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care

2013;36:403-9. Crossref

19. Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, et al. New definition

for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of

the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clin Orthop Relat

Res 2011;469:2992-4. Crossref

20. Capozzi JD, Lepkowsky ER, Callari MM, Jordan ET,

Koenig JA, Sirounian GH. The prevalence of diabetes

mellitus and routine hemoglobin A1c screening in

elective total joint arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty

2017;32:304-8. Crossref

21. Jämsen E, Nevalainen P, Eskelinen A, Huotari K,

Kalliovalkama J, Moilanen T. Obesity, diabetes, and

preoperative hyperglycemia as predictors of periprosthetic

joint infection: a single-center analysis of 7181 primary hip

and knee replacements for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg

Am 2012;94:e101. Crossref

22. Kheir MM, Tan TL, Kheir M, Maltenfort MG, Chen AF.

Postoperative blood glucose levels predict infection

after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am

2018;100:1423-31. Crossref

23. Chrastil J, Anderson MB, Stevens V, Anand R, Peters CL,

Pelt CE. Is hemoglobin A1c or perioperative hyperglycemia

predictive of periprosthetic joint infection or death

following primary total joint arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty

2015;30:1197-202. Crossref

24. Nathan DM, Davidson MB, DeFronzo RA, et al.

Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance:

implications for care. Diabetes Care 2007;30:753-9. Crossref

25. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al.

Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle

intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393-

403. Crossref

26. Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained

reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle

intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention

Study. Lancet 2006;368:1673-9. Crossref

27. Wang J, Zhu C, Cheng T, et al. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of antibiotic-impregnated bone cement

use in primary total hip or knee arthroplasty. PLoS One

2013;8:e82745. Crossref

28. Sebastian S, Liu Y, Christensen R, Raina DB, Tägil M,

Lidgren L. Antibiotic containing bone cement in

prevention of hip and knee prosthetic joint infections: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Translat

2020;23:53-60. Crossref

29. Timmons JG, Cunningham SG, Sainsbury CA, Jones GC.

Inpatient glycemic variability and long-term mortality

in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes

Complications 2017;31:479-82. Crossref

30. Hanefeld M, Sulk S, Helbig M, Thomas A, Kohler C.

Differences in glycemic variability between normoglycemic

and prediabetic subjects. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2014;8:286-

90. Crossref

31. Brownlee M, Hirsch IB. Glycemic variability: a hemoglobin

A1c-independent risk factor for diabetic complications.

JAMA 2006;295:1707-8. Crossref

32. Nusca A, Tuccinardi D, Albano M, et al. Glycemic variability

in the development of cardiovascular complications in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2018;34:e3047. Crossref

33. Shohat N, Restrepo C, Allierezaie A, Tarabichi M, Goel R,

Parvizi J. Increased postoperative glucose variability is

associated with adverse outcomes following total joint

arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:1110-7. Crossref

34. Wilson JM, Jungner YG. Principles and practice of

screening for disease [in Spanish]. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam

1968;65:281-393.

35. Ko GT, Tang J, Chan JC, et al. Lower BMI cut-off value to

define obesity in Hong Kong Chinese: an analysis based on

body fat assessment by bioelectrical impedance. Br J Nutr

2001;85:239-42. Crossref

36. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index

for Asian populations and its implications for policy and

intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63. Crossref

37. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of

hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report

by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the

European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).

Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669-701. Crossref

38. Shohat N, Tarabichi M, Tischler EH, Jabbour S, Parvizi J.

Serum fructosamine: a simple and inexpensive test for

assessing preoperative glycemic control. J Bone Joint Surg

Am 2017;99:1900-7. Crossref

39. Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip

arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:1746-51. Crossref

40. Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of

revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin

Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:45-51. Crossref

41. Delanois RE, Mistry JB, Gwam CU, Mohamed NS,

Choksi US, Mont MA. Current epidemiology of revision

total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty

2017;32:2663-8. Crossref

42. Sculco TP. The economic impact of infected total joint

arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect 1993;42:349-51.

43. Parvizi J, Pawasarat IM, Azzam KA, Joshi A, Hansen EN,

Bozic KJ. Periprosthetic joint infection: the economic

impact of methicillin-resistant infections. J Arthroplasty

2010;25(6 Suppl):103-7. Crossref

44. Golden SH, Yajnik C, Phatak S, Hanson RL, Knowler WC.

Racial/ethnic differences in the burden of type 2 diabetes

over the life course: a focus on the USA and India.

Diabetologia 2019;62:1751-60. Crossref

45. Bozic KJ, Lau E, Kurtz S, Ong K, Berry DJ. Patient-related

risk factors for postoperative mortality and periprosthetic

joint infection in Medicare patients undergoing TKA. Clin

Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:130-7. Crossref

46. Zhu Y, Zhang F, Chen W, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang Y. Risk

factors for periprosthetic joint infection after total joint

arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J

Hosp Infect 2015;89:82-9. Crossref