Prevalences of levofloxacin resistance and pncA mutation in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Hong Kong

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prevalences of levofloxacin resistance and pncA

mutation in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Hong Kong

Kevin KM Ng, MB, ChB, FRCPath; Peter CW Yip, PhD; Patricia KL Leung, MPhil

Department of Public Health Laboratory Services Branch, Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kevin KM Ng (kevinkmng@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: In 2018, the World Health

Organization recommended a 6-month treatment

regimen that included levofloxacin and pyrazinamide

for isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis

without rifampicin resistance (Hr-TB). Susceptibility

testing for both drugs is not routinely performed

for Hr-TB in Hong Kong. This study examined

the prevalences of levofloxacin and pyrazinamide

resistances in Hr-TB and explored associated risk

factors.

Methods: All Hr-TB isolates archived during 2018

were retrieved. Isolates were de-duplicated to

identify unique cases. Levofloxacin susceptibility

testing was performed using the MGIT 960 System;

pncA gene sequencing was used as a surrogate

indicator of pyrazinamide susceptibility. Previous

laboratory records for each case were analysed.

Results: In total, 160 phenotypic Hr-TB cases were

identified from among 3411 patients with tuberculosis

(4.7%). Among these, 157 were analysed, revealing

0.6% (n=1) levofloxacin resistance and 4.5% (n=7) pyrazinamide resistance, respectively. Independent

risk factors associated with pncA mutations included

history of tuberculosis in the affected patient and

isoniazid poly-resistance (ie, double and triple

resistances), but not mono-resistance.

Conclusion: For Hr-TB in Hong Kong, levofloxacin

resistance is rare and pyrazinamide resistance-associated

pncA mutations are uncommon. Routine

susceptibility testing for these drugs is not indicated

unless related risk factors are identified.

New knowledge added by this study

- Levofloxacin (LVX) resistance is rare (0.6%) and pyrazinamide (PZA) resistance-associated pncA mutations are uncommon (4.5%) among isoniazid-resistant, rifampicin-susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Hr-TB) isolates in Hong Kong.

- Risk factors for pncA mutations in Hr-TB include history of tuberculosis in the affected patient and isoniazid poly-resistance.

- Clinicians could initiate empirical treatment for patients with Hr-TB without routine susceptibility testing for LVX and PZA.

- Susceptibility testing for LVX and PZA could be considered in patients with Hr-TB and additional risk factors; or when clinical, radiological, and microbiological responses are suboptimal during early follow-up.

Introduction

There has been a gradual decline in the global

tuberculosis (TB) incidence and mortality rates

over time, by approximately 2% and 3% per year,

respectively.1 Despite this trend, TB remains a leading

cause of death, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug

resistance continues to be a major public health issue.

Globally, isoniazid (INH)-resistant, rifampicin (RIF)-susceptible TB (Hr-TB) is the most common drug-resistant

form of disease.2 In 2017, the rates of Hr-TB were 7.1% among patients with new TB diagnoses

and 7.9% in patients who had previously undergone treatment for TB.1 In Hong Kong, the respective

rates were 5.3% and 9.5%, with a combined rate of

5.7% in 2016.3 The Hr-TB is associated with worse

clinical outcome and development of multidrug

resistance (MDR),4 5 although the findings have been

inconsistent.6 7

Isoniazid constitutes a key component in

the treatment of drug-susceptible TB, through

its inhibition of mycolic acid biosynthesis in the

mycobacterial cell wall. Over 85% of INH resistance

is conferred by mutations residing in the katG gene

and inhA promoter region,8 leading to high and low levels of resistance, respectively. These mutations

can readily be detected by commercial molecular

line-probe assays. The level of resistance can also

vary according to the co-occurrences of less common

mutations in other regions.

For the treatment of Hr-TB, current World

Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommend

6 months of RIF, pyrazinamide (PZA), ethambutol,

and levofloxacin (LVX). The guidelines also

recommend examination of resistances towards

fluoroquinolones and PZA, prior to treatment.9

In our locality, routine testing of LVX and

PZA susceptibility has not been implemented for

the treatment of Hr-TB. To determine the most

cost-effective testing strategy, this study reviewed

an annual collection of Hr-TB isolates, with the aim

of determining the prevalences of LVX resistance

and pncA mutations (as a molecular marker of

PZA resistance in Hr-TB) and identifying factors

associated with these resistances.

Methods

Case identification and data collection

Data were reviewed from the TB Reference

Laboratory of the Department of Health. This

laboratory processes local M tuberculosis strains

from specimens collected in out-patient clinics

and in-patient hospitals in both public and private

sectors. All phenotypic Hr-TB isolates in 2018 were

identified and de-duplicated using unique patient

identifiers. The following data were included in this

analysis: basic patient demographics, phenotypic susceptibility results of first-line drugs (INH at

critical concentrations 0.1 μg/mL and 0.4 μg/mL as

recommended by the WHO, RIF, streptomycin, and

ethambutol), and genotypic susceptibility results

(inhA promoter region, katG codon 315, and rpoB

hotspot region) from the GenoType MTBDRplus

assay, version 2.0 (Hain Lifescience). Any discrepant

or unsuccessful test results were resolved by the agar

proportion method and/or DNA sequencing; when

applicable, these additional data were reported as the

final results. All available data from the Laboratory

Information System were reviewed for each patient

to determine any history of TB, fluorescence

microscopy results (according to Global Laboratory

Initiative grading10), site of isolation (pulmonary

versus extrapulmonary), any documented sputum

culture conversion and the duration (ie, time between

the date of first positive culture for current infection

and the date of consistently negative culture), and

microbiological outcome.

Levofloxacin and pyrazinamide susceptibility

testing and pncA gene sequencing

Selected M tuberculosis strains were retrieved

from the laboratory archive and sub-cultured,

then subjected to LVX susceptibility testing

using the BD BACTEC MGIT 960 system

(Becton, Dickson and Company), in accordance

with the manufacturer’s instructions. The LVX

critical concentration at 1.0 μg/mL was used as

recommended by the WHO. DNA extraction was

performed using GenoLyse (Hain Lifescience).

The pncA gene was amplified with the primers

pncA-1F (5′-CGCTCAGCTGGTCATGTTC-3′) and

pncA-1R (5′-CCCACCGGGTCTTCGAC-3′) to

produce an amplicon of 798 bp, using the GeneAmp

PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). Each 25-μL

reaction mixture contained 12.5 μL of GoTaq G2 Hot

Start Colorless Master Mix (Promega) [1×], 0.25 μL

of each primer (1.0 pM/μL), 9.5 μL PCR-grade water,

and 2.5 μL of template DNA. Reaction mixtures

were amplified using the following protocol:

2 minutes at 95°C; 35 cycles of 1 min at 95°C,

1 minute at 65°C, and 1 minute at 72°C; and 10 minutes

at 72°C. Sequencing was performed using the

3730 × l DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) with the

same primers. Resulting sequences were compared

with the sequence of wild-type M tuberculosis

H37Rv for detection of pncA mutations. Strains

with detected pncA mutations were subjected to

further analysis of PZA susceptibility via the MGIT

960 system in accordance with the manufacturer’s

instructions, with a critical concentration of

100 μg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis comprised odds ratio calculations

and Fisher’s exact test. Firth logistic regression was employed for multivariable analysis because of

the low outcome frequency. IBM SPSS Statistics

Subscription (Windows version, IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], United States) was used for data analysis. A P

value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This article complies with the STROBE Statement

reporting guidelines.

Results

In total, 8865 M tuberculosis isolates from 3411

patients were processed in 2018. Susceptibility

profiles were available for all except repeated strains

collected from the same patient within 3 months.

De-duplication of 393 isolates yielded 160 patients

with phenotypic Hr-TB, amounting to a case rate

of 4.7%. rpoB hotspot mutations were identified

in five cases by GenoType MDRTBplus, three of

which were confirmed to confer RIF resistance

according to rpoB sequencing results. These three

cases were considered to be RIF-resistant and

excluded from further analysis. The mean age of the

patients in the remaining 157 cases was 61.3 years

(range, 15-95 years); the male to female ratio was

1.8. Pulmonary TB was present in 90.4% of affected

patients (n=142), while 9.6% of affected patients

(n=15) had extrapulmonary involvement. There was

a documented history of TB by positive culture in

4.5% of affected patients (n=7). Microscopy results

were available for cases in which direct specimens

were received by our laboratory at the time of initial

diagnosis (n=45). The majority of specimens was

acid-fast bacillus smear-negative (n=33), followed by

1-4 acid-fast bacilli per length (n=4), scanty (n=4),

1+ (n=2), and 2+ and 3+ (n=1 each). In terms of

microbiological outcome, 76.4% of affected patients

(n=120) had documented sputum culture conversion

without recurrence after follow-up of at least

9 months, among which 106 attained conversion

within 5 months after diagnosis. The median interval

required for culture conversion was 72.5 days (range,

9-622 days). No clearance was documented for

patients in the remaining 37 cases, for whom no

follow-up specimens were received for >1 year.

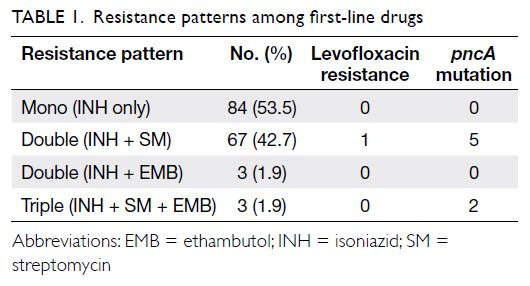

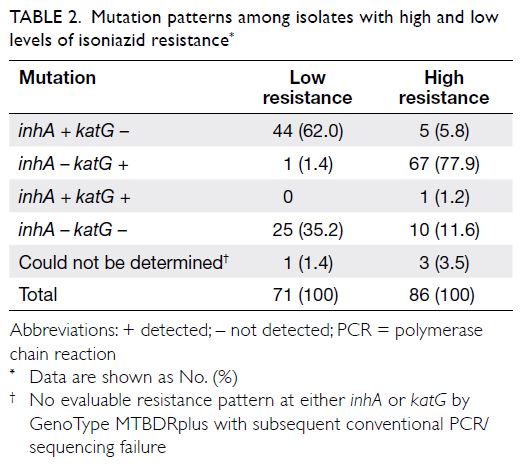

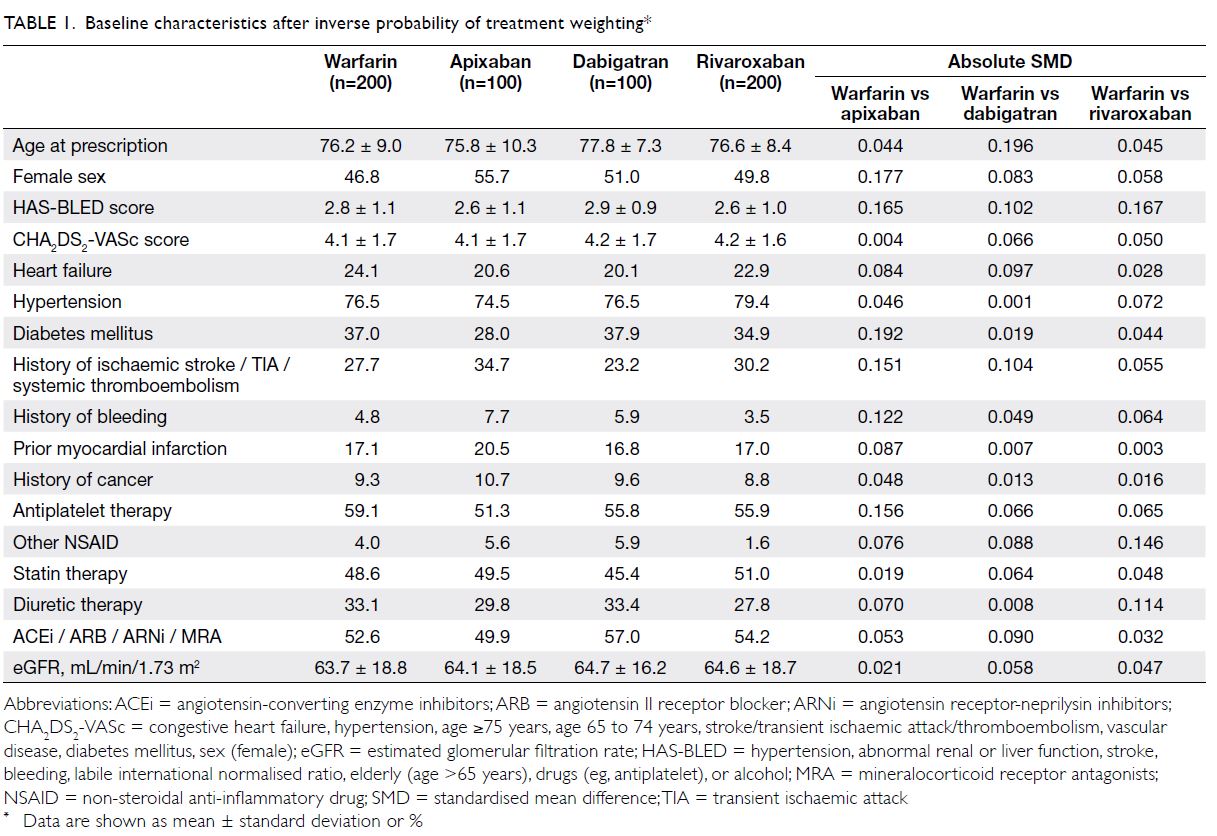

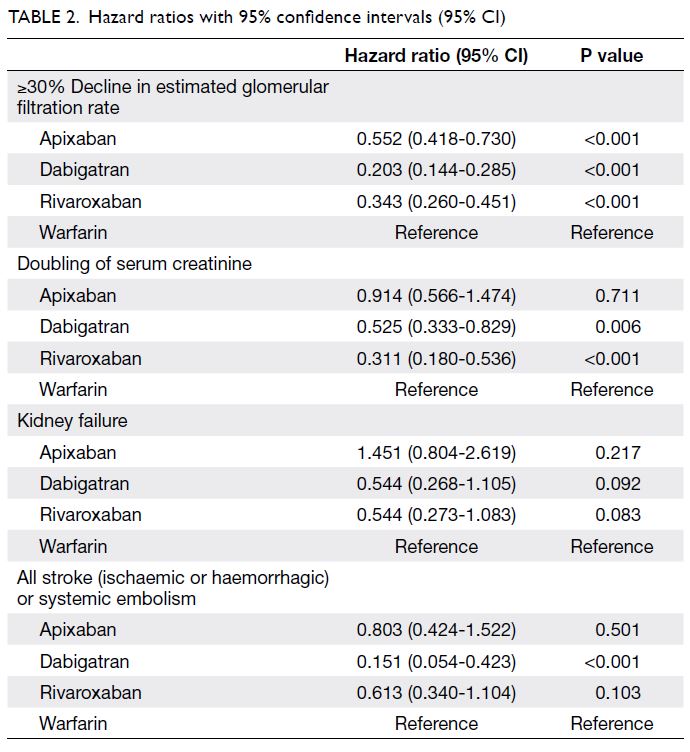

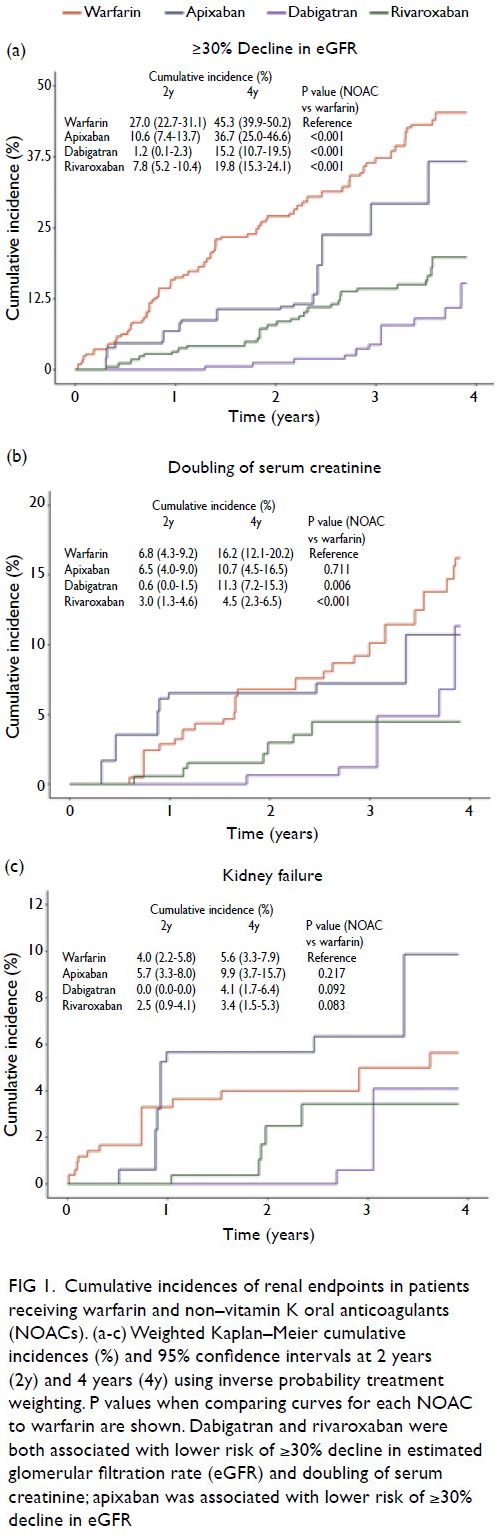

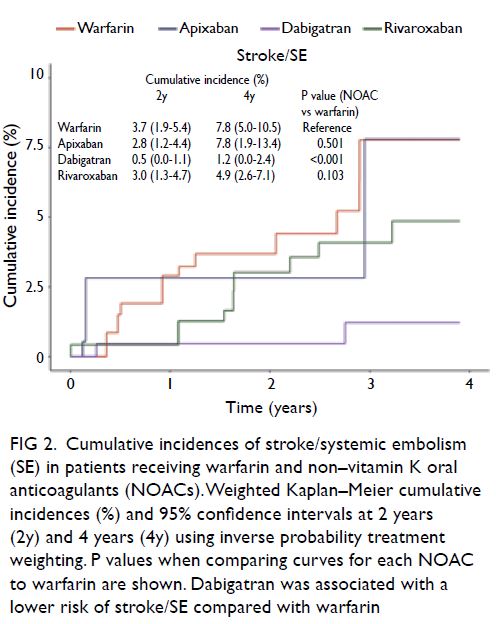

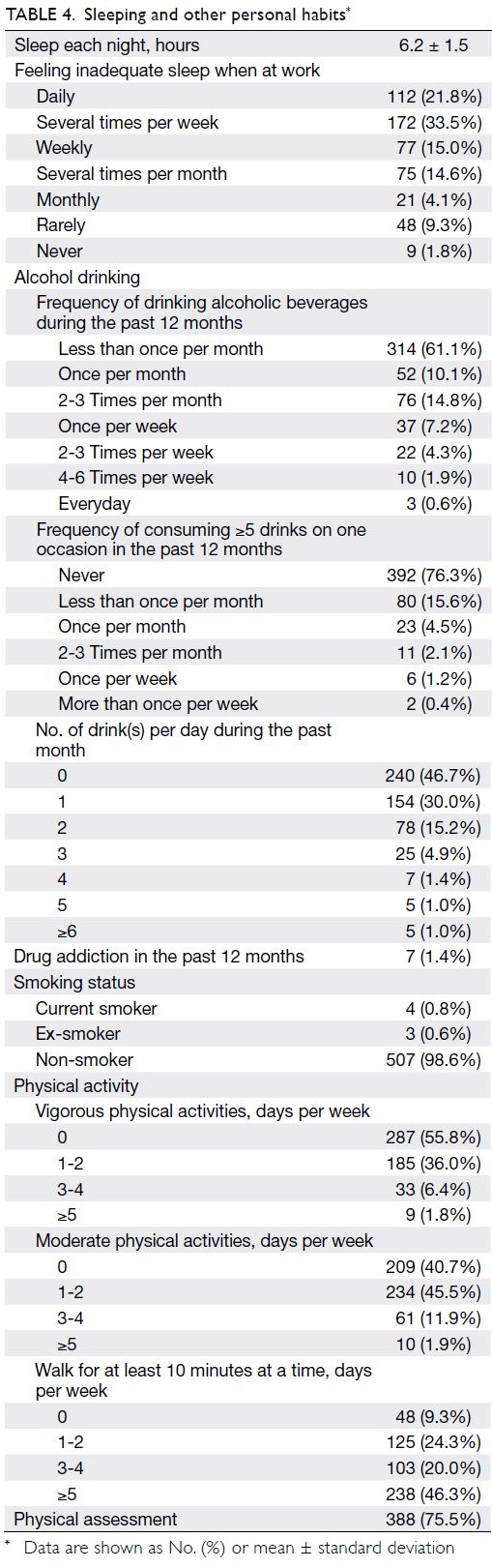

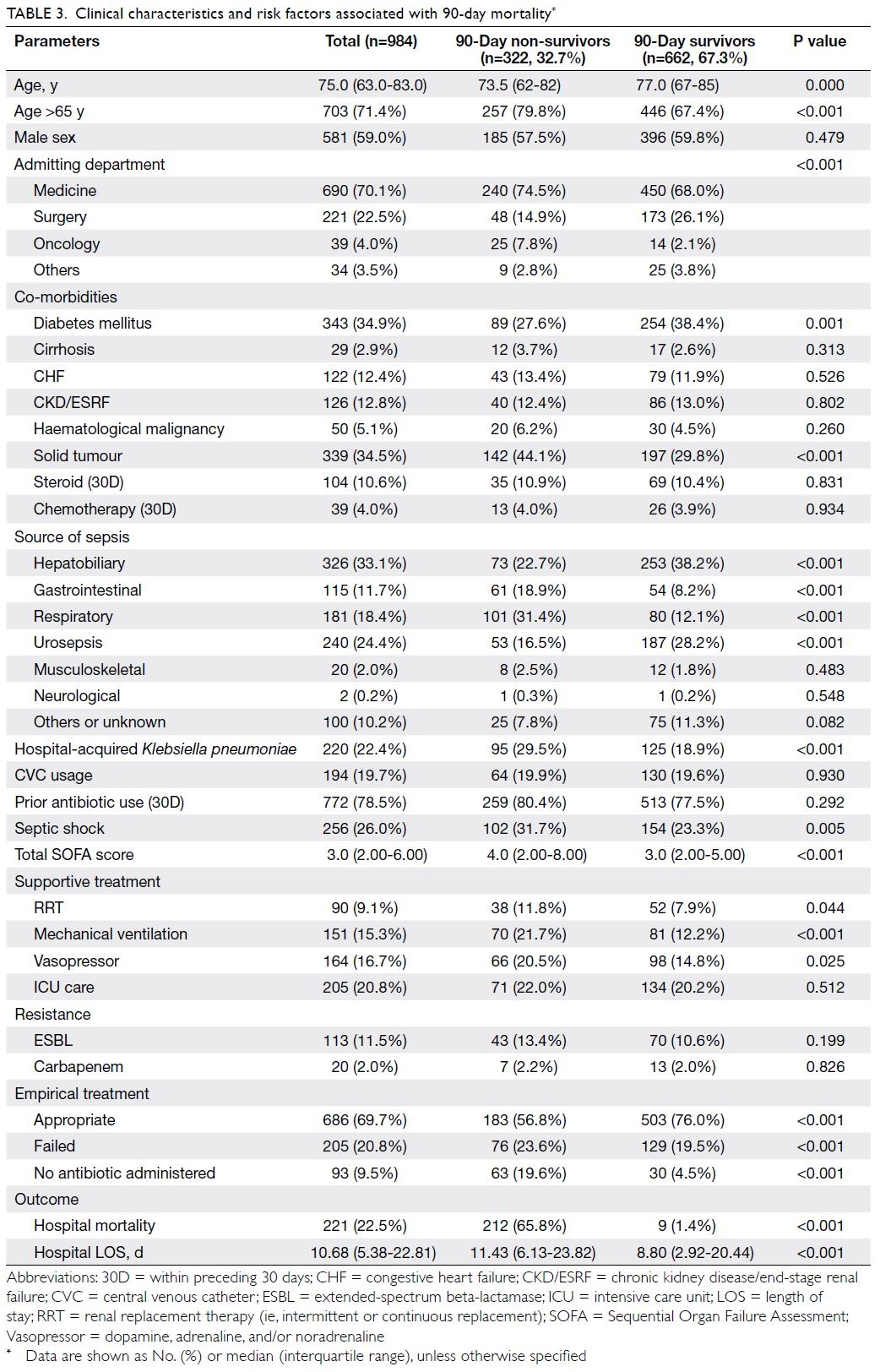

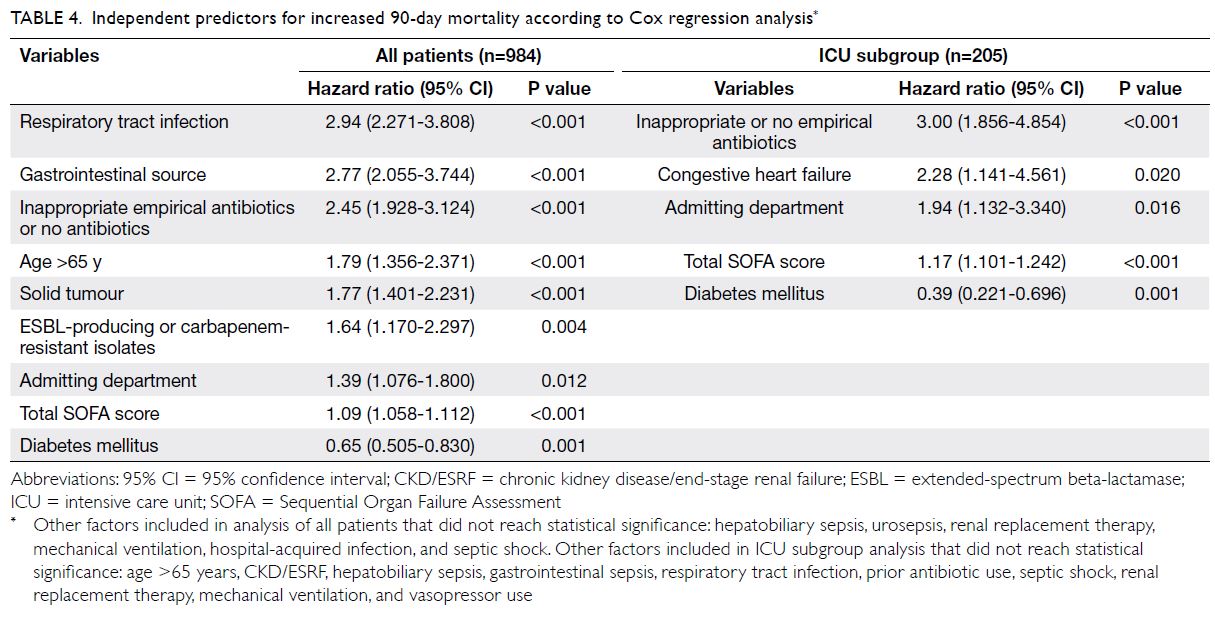

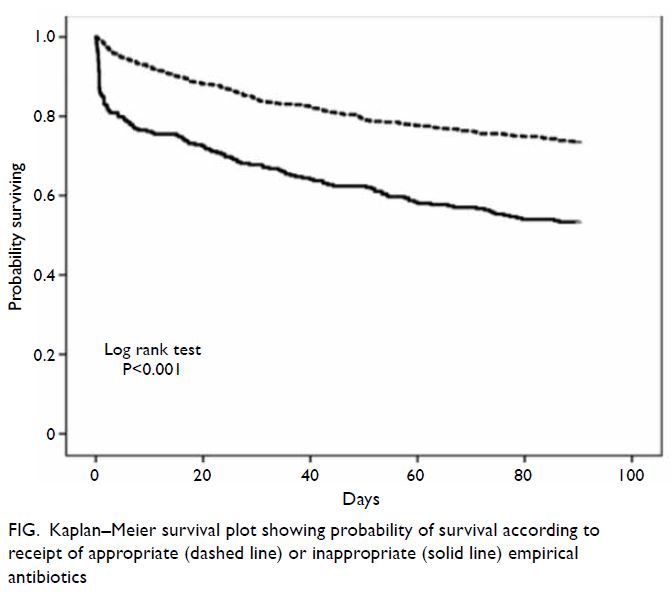

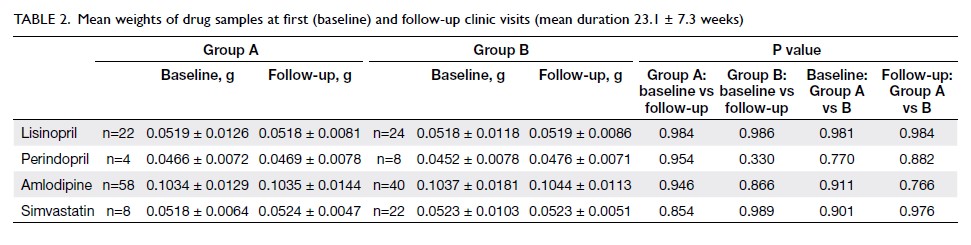

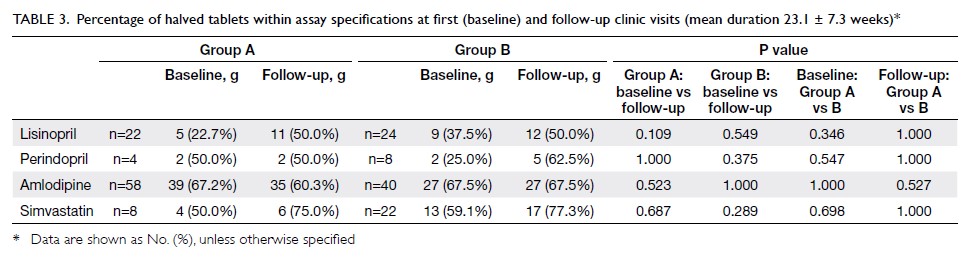

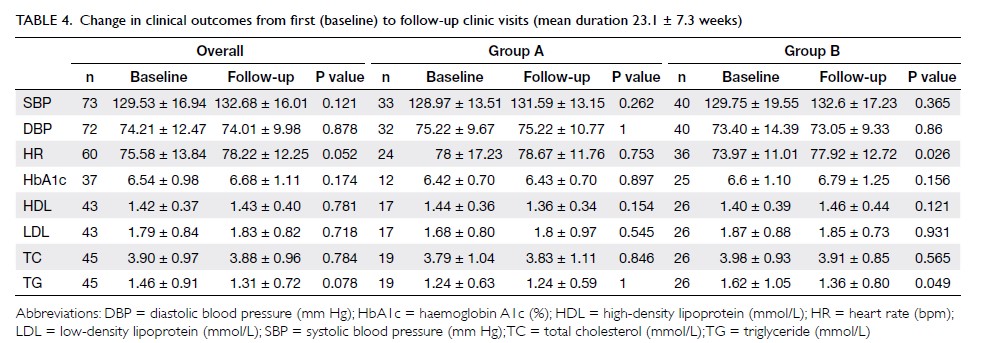

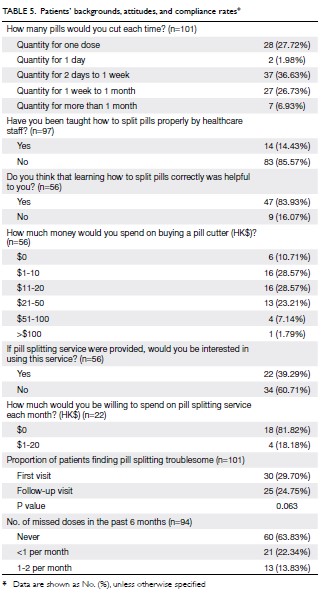

Table 1 shows the patterns of resistance among

first-line drugs and distributions of cases with LVX

resistance and pncA mutations. Table 2 shows the

patterns of mutations detected. With respect to

INH, 45.2% (n=71) of the isolates exhibited low-level

resistance (minimum inhibitory concentration

0.1-0.4 μg/mL) and 54.8% (n=86) of the isolates

exhibited high-level resistance (minimum inhibitory

concentration >0.4 μg/mL).

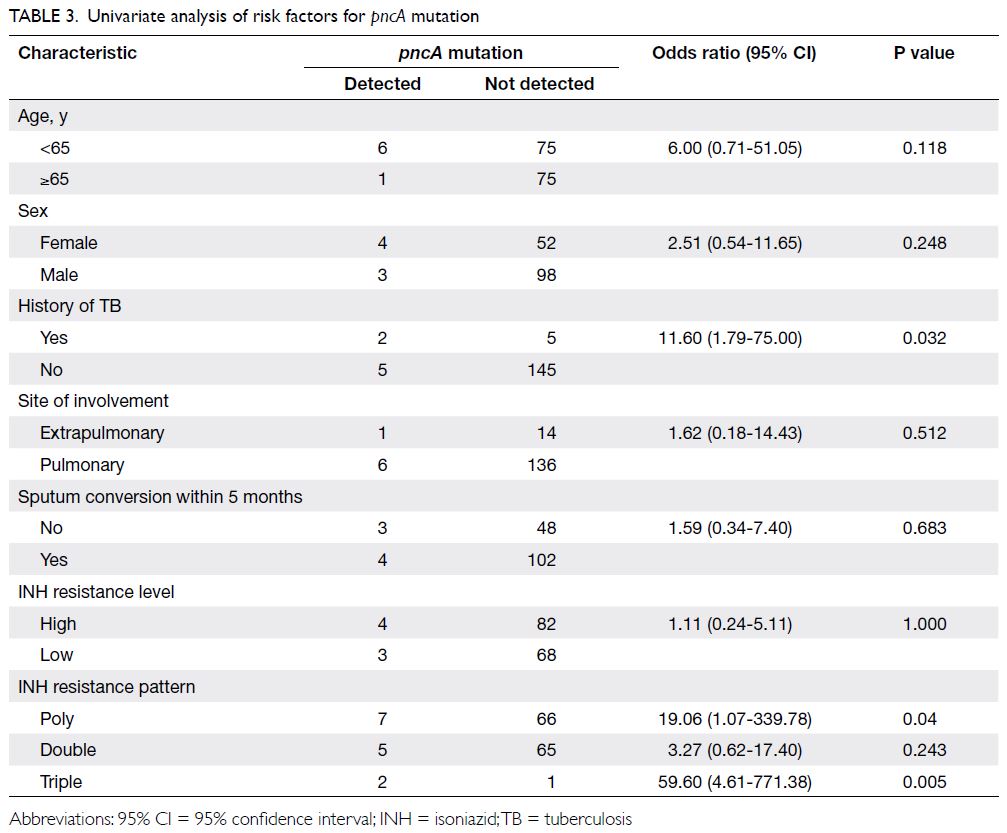

For LVX, only one strain was resistant, while

155 were sensitive (one isolate failed to be recovered).

The number of resistant cases was insufficient for

correlation analysis. pncA mutations were detected

in 4.5% (7/157 cases), and all detected mutations were

previously identified as PZA resistance–related. All isolates with pncA mutations were phenotypically

resistant to PZA. Univariate analysis showed that

pncA mutations were associated with documented

history of TB in the affected patient (odds ratio

[OR]=11.60, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.79-75.00; P=0.03) and INH poly-resistance (OR=19.06,

95% CI=1.07-339.78; P=0.04) but not mono-resistance,

as shown in Table 3. In multivariable

logistic regression, pncA mutations were associated

with documented history of TB in the affected

patient (OR=18.03, 95% CI=2.25-153.85; P=0.008),

INH triple resistance (OR=409.11, 95% CI=6.52

to >1000; P<0.001), and INH double resistance

(OR=13.50, 95% CI=1.43 to >1000; P=0.019).

Discussion

Levofloxacin resistance

In this study, the frequency of LVX resistance was

very low in Hr-TB. Levofloxacin is an important drug

in the management of drug-resistant TB. In a 2009

study in Shanghai, Xu et al11 estimated the rates of

LVX resistance to be 1.9% in strains pan-susceptible to

first-line drugs, 6.7% in INH mono-resistant strains,

and ≤25% in MDR-TB. Independent risk factors associated with LVX resistance included MDR, RIF

mono-resistance, poly-resistance (resistance to ≥2

first-line drugs, but not MDR), age ≥46 years, and TB

re-treatment, but not INH mono-resistance. These

findings were consistent with the results of a 2017

study in Ningbo (a city near Shanghai), whereby Che

et al12 revealed no LVX resistance in strains pan-susceptible

to first-line drugs, 3% in strains with any

resistance to first-line drugs except MDR, and ≤30%

in MDR-TB. Most fluoroquinolone resistance was

present in the MDR group. Che et al12 also found that

prevalence of LVX resistance in MDR-TB increased

with duration of inappropriate treatment before LVX;

this relationship was stronger than any relationships

with previous fluoroquinolone exposures. Further

studies are needed to determine whether this finding

also applies to Hr-TB. Levofloxacin resistance is

uncommon in non-MDR strains, especially in

the present study. Since 2015, our laboratory has

performed LVX susceptibility testing on 640 Hr-TB

strains, identifying only two resistant cases (0.31%;

unpublished data), including the one in this study.

Clinicians could treat affected patients empirically, in accordance with WHO recommendations;

further testing could be arranged based on clinical,

radiological, and microbiological responses during

early follow-up. In patients with Hr-TB that exhibits

LVX resistance or poly-resistance to other primary

agents, individualised adjustment of the treatment

regimen is recommended in accordance with WHO

guidelines9 (eg, exclusion of LVX or inclusion of

second-line TB medicines). In our single case

with LVX resistance, the patient had no history

of TB. His sputum acid-fast bacillus smear result

was 2+. The Hr-TB strain isolated was initially

LVX-sensitive without mutations in rpoB, gyrA, or

gyrB on diagnosis and follow-up at 8 months.

The patient continued to exhibit sputum culture-positive

results after 15 months of treatment; further

analysis revealed that the isolate had acquired

gyrA mutation (detected by line-probe assays) and

LVX phenotypic resistance. It then developed into

an MDR strain; the patient eventually achieved

culture conversion at approximately 18 months

after diagnosis. Underlying hetero-resistance was a

possible contributing factor.

Pyrazinamide resistance

Phenotypic PZA susceptibility testing has often been

problematic. pncA mutations constitute the most

common and primary determinant of PZA resistance,

with reported sensitivity of approximately 80% to

95% and specificity of approximately 85% to 100%.13 14

Resistance-conferring mutations are known to be

diverse and scattered over the gene’s full length. Our

seven isolates all had unique mutations (Gln10Arg,

His51Tyr, Trp68Stop, Thr47Pro, Ala102Thr,

Asp63Gly, and Val139Ala), which were associated

with PZA resistance at a high probability of 0.985

according to available literature15 (except Val139Ala,

probability of resistance=0.783). These seven isolates

were also confirmed to be phenotypically resistant to

PZA in our study.

Thus far, investigations of phenotypic and

genotypic PZA resistance have generally focused

on MDR-TB. Concerning non-MDR-resistant

strains, there is considerable geographical variation

in the reported rates, from 2.92% to 4.8% in the

United States,16 17 to 24% in the Western Pacific and

75% in South East Asia.18 For Hr-TB in particular,

phenotypic PZA resistance was reported in 2% of

INH mono-resistant strains in South Africa,19 no

PZA resistance was detected (phenotypic or pncA

mutation) in Georgia (Eastern Europe) among

Hr-TB strains,20 and ≤14.9% of Hr-TB strains

exhibited pncA mutations in Vietnam.21 In our

study, we observed that 4.5% of Hr-TB isolates had

pncA mutations. Such variation may be related to

multiple factors, including differences in inclusion

criteria, testing method, treatment, infection control

practice, and disease burden. In terms of risk factors,

we found that history of TB in the affected patient

and poly-resistance (but not mono-resistance) were

significantly associated with pncA mutations. These

results are consistent with findings from previous

studies, which also showed an association with

MDR.21 22 23 Clinicians are advised to consider the

possibility of PZA resistance in patients with Hr-TB

and these risk factors. Routine testing for LVX or

PZA susceptibility in patients with INH mono-resistant

TB alone (ie, no other risk factors) is not

considered cost-effective, based on our findings.

Outcomes and treatment of isoniazidresistant

Mycobacterium tuberculosis without rifampicin resistance

In our study, most patients with Hr-TB had a

satisfactory microbiological outcome without

recurrence. However, the outcome was unknown in

23.6% of cases. Most of these involved patients were

diagnosed and managed in hospitals, where only

positive isolates were subjected to reference testing

at our laboratory. Based on the recommended

management regimen for TB in Hong Kong, these patients would have been followed up until sputum

culture conversion. Considering the time elapsed

since the latest positive laboratory result, the patients

in most cases with unknown outcomes likely already

had culture conversion.

In general, Hr-TB is presumably associated

with higher rates of treatment failure and MDR

acquisition, compared with drug-susceptible

strains.4 5 Important considerations for disease

control include recognition of risk factors

associated with Hr-TB (eg, history of TB treatment,

incarceration in prisons, and homelessness7 24),

early detection of INH resistance, exclusion of RIF

resistance by appropriate molecular methods (eg,

line-probe assays),2 and compliance with current

treatment guidelines. With the maturation of whole-genome

sequencing, the technology is becoming

integrated into the local routine drug susceptibility

testing protocol for all M tuberculosis isolates;

multiple and uncommon molecular markers of drug

resistance might thus be identified earlier in a single

set of assays for proper treatment guidance.

Strengths and limitations

Because our laboratory serves as a local TB reference

laboratory, this study was able to use a representative

M tuberculosis collection that reflected the status

of Hr-TB in Hong Kong. Furthermore, because

our laboratory serves as a supranational reference

laboratory, we were able to perform an array of

confirmatory tests in accordance with WHO

recommendations, thus ensuring reliable results.

However, this study had some limitations. First,

it lacked data regarding microscopy results, drug

treatment, and clinical outcome, thus preventing

a more comprehensive assessment. Second, the

small sample size and low outcome frequencies of

LVX and PZA non-susceptibilities led to limited

correlation analysis. Third, less common mutations

mediating INH resistance were not examined to

determine their prevalences; Hr-TB cases with these

mutations would only be identified on the basis of

phenotypic results. A substantial proportion of cases

(22.3%; n=35) had negative GenoType MDRTBplus

results. Because this test only detects the most common mutations at the inhA promoter region

and katG codon 315, other relevant mutations might

have been missed. Furthermore, in 3.2% (n=5) of

cases with high-level INH resistance, mutations

were detected in the inhA promoter region alone.

The availability of preliminary information before

receiving the INH phenotypic susceptibility results

might lead to mismanagement of patient treatment

(eg, INH inclusion in the therapeutic regimen).

Fourth, low-level RIF resistance mediated by

mutations outside the rpoB hotspot region and

undetected by phenotypic testing was not ruled out in this study. Inclusion of such isolates might have

led to overestimation of true resistance in Hr-TB.

Fifth, PZA resistance could be mediated by other

less common mutations, which were not examined

by performing phenotypic PZA susceptibility

testing on all Hr-TB isolates; thus, we may have

underestimated its prevalence. Our laboratory has

found that all PZA-resistant M tuberculosis isolates

thus far could be confirmed through pncA mutation

analysis. Nevertheless, we presume that these

limitations do not greatly affect the reliability and

overall interpretation of our findings.

Conclusion

In Hong Kong, the rate of Hr-TB was 4.7% among

active TB cases in 2018. Levofloxacin and PZA

resistances among Hr-TB were uncommon (0.6%

and 4.5%, respectively). History of TB in the affected

patient and INH poly-resistance, including both

double and triple resistances, were independent risk

factors for pncA mutations. The findings from this

study do not support routine susceptibility testing

for these two drugs in patients with INH mono-resistant

TB who lack additional risk factors.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KKM Ng.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKM Ng.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KKM Ng.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKM Ng.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KKM Ng.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the excellent work and contribution by staff, especially Mr Steven CW Lui and Ms Angela WL

Lau, at the Tuberculosis Laboratory and Special Investigation

Laboratory of Public Health Laboratory Services Branch,

Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government (Ref: LM 425/2019). All included patients

consented to testing for tuberculosis.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis

report 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed 19 Sep 2019.

2. Romanowski K, Campbell JR, Oxlade O, Fregonese F, Menzies D, Johnston JC. The impact of improved

detection and treatment of isoniazid resistant tuberculosis

on prevalence of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis: a

modelling study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0211355. Crossref

3. Tuberculosis & Chest Service of Department of Health,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2016. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/Annual_Report_2016.pdf. Accessed 19 Sep 2019.

4. Gegia M, Winters N, Benedetti A, van Soolingen D,

Menzies D. Treatment of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis

with first-line drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:223-34. Crossref

5. Karo B, Kohlenberg A, Hollo V, et al. Isoniazid (INH)

mono-resistance and tuberculosis (TB) treatment success:

analysis of European surveillance data, 2002 to 2014. Euro

Surveill 2019;24:1800392. Crossref

6. Salindri AD, Sales RF, DiMiceli L, Schechter MC, Kempker RR, Magee MJ. Isoniazid monoresistance and

rate of culture conversion among patients in the State of

Georgia with confirmed tuberculosis, 2009-2014. Ann Am

Thorac Soc 2018;15:331-40. Crossref

7. Cattamanchi A, Dantes RB, Metcalfe JZ, et al. Clinical

characteristics and treatment outcomes of isoniazid-monoresistant

tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:179-85. Crossref

8. Seifert M, Catanzaro D, Catanzaro A, Rodwell TC.

Genetic mutations associated with isoniazid resistance

in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. PLoS

One 2015;10:e0119628. Crossref

9. World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Available from:

https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2019/consolidated-guidelines-drug-resistant-TB-treatment/en/. Accessed 19

Sep 2019. Crossref

10. Global Laboratory Initiative. Mycobacteriology Laboratory Manual. 1st ed. Global Laboratory Initiative; 2014

11. Xu P, Li X, Zhao M, et al. Prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance among tuberculosis patients in Shanghai, China.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:3170-2. Crossref

12. Che Y, Song Q, Yang T, Ping G, Yu M. Fluoroquinolone

resistance in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium

tuberculosis independent of fluoroquinolone use. Eur

Respir J 2017;50:1701633. Crossref

13. Streicher EM, Maharaj K, York T, et al. Rapid sequencing of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis pncA gene for detection of pyrazinamide susceptibility. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:4056-7. Crossref

14. Khan MT, Malik SI, Ali S, et al. Pyrazinamide resistance

and mutations in pncA among isolates of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. BMC

Infect Dis 2019;19:116. Crossref

15. Miotto P, Cabibbe AM, Feuerriegel S, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pyrazinamide resistance determinants: a

multicenter study. mBio 2014;5:e01819-4.Crossref

16. Kurbatova EV, Cavanaugh JS, Dalton T, Click ES, Cegielski

JP. Epidemiology of pyrazinamide-resistant tuberculosis in

the United States, 1999-2009. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:1081-93. Crossref

17. Budzik JM, Jarlsberg LG, Higashi J, et al. Pyrazinamide resistance, Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineage and

treatment outcomes in San Francisco, California. PLoS

One 2014;9:e95645. Crossref

18. Whitfield MG, Soeters HM, Warren RM, et al. A global perspective on pyrazinamide resistance: systematic review

and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133869. Crossref

19. Whitfield MG, Streicher EM, Dolby T, et al. Prevalence of pyrazinamide resistance across the spectrum of drug

resistant phenotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2016;99:128-30. Crossref

20. Sengstake S, Bergval IL, Schuitema AR, et al. Pyrazinamide resistance-conferring mutations in pncA and the

transmission of multidrug resistant TB in Georgia. BMC

Infect Dis 2017;17:491. Crossref

21. Huy NQ, Lucie C, Hoa T, et al. Molecular analysis of

pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis

in Vietnam highlights the rate of pyrazinamide resistance-associated

mutations in clinical isolates. Emerg Microbes

Infect 2017;6:e86. Crossref

22. Li D, Hu Y, Werngren J, et al. Multicenter study of the emergence and genetic characteristics of pyrazinamide-resistant

tuberculosis in China. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother 2016;60:5159-66. Crossref

23. Chiu YC, Huang SF, Yu KW, Lee YC, Feng JY, Su JY. Characteristics of pncA mutations in multidrug-resistant

tuberculosis in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:240. Crossref

24. Smith CM, Trienekens SC, Anderson C, et al. Twenty years and counting: epidemiology of an outbreak of isoniazid-resistant

tuberculosis in England and Wales, 1995 to 2014.

Euro Surveill 2017;22:30467. Crossref