Hong Kong Med J 2020 Jun;26(3):208–15 | Epub 4 Jun 2020

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Communication skills of providers at primary

healthcare facilities in rural China

Q Zhou, MSc1; Q An, MSc1; N Wang, MSc1; Jason Li, BS2; Y Gao, MD, PhD3; J Yang, PhD1; J Nie, PhD1; Q Gao, PhD1; H Xue, PhD1

1 Center for Experimental Economics in Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

2 Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, United States

3 Cadre Training Centre, National Health and Family Planning Commission of People’s Republic of China, Beijing, China

Corresponding author: Ms J Yang (jyang0716@163.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Effective provider-patient communication has been confirmed to improve

diagnosis, treatment planning, health outcomes,

patient satisfaction, and treatment compliance.

Few studies have measured the effectiveness

of communication between patients and rural

providers in China. To fill this gap in the literature,

the present study describes the communication skills

of providers at primary healthcare facilities in rural

China and investigates the provider- and facility-level

factors underlying these communication skills.

Methods: The standardised patients successfully

completed 504 interactions across two tiers of China’s

rural health system and engaged with providers

at village clinics and township health centres. We

assessed providers’ communication skills based on

recorded interactions between the providers and the

standardised patients using the SEGUE Framework,

which contains the following five dimensions: ‘Set

the stage’, ‘Elicit information’, ‘Give information’,

‘Understand the patient’s perspective’, and ‘End the

encounter’.

Results: The providers’ overall average score was

50.6% on the SEGUE communication tasks. They did

well in ‘Set the stage’ (54.4%) and ‘Elicit information’

(56.2%) but performed poorly in ‘End the encounter’

(24.5%) and ‘Understand the patient’s perspective’

(44.0%). Female and younger providers scored 0.75 (P<0.05) and 0.04 (P<0.01) points higher than their

male and older counterparts on total SEGUE score,

respectively.

Conclusion: Providers in rural China had relatively

poor communication skills overall, especially in

terms of their demonstration of care for patients

and inviting them to participate in the interaction.

Gender and age were significantly associated with

providers’ level of communication skills in rural

China.

New knowledge added by this study

- Rural providers in China scored 50.6% on the SEGUE Framework, revealing relatively poor communication skills.

- No correlations were found between education level and communication skills in rural China.

- The ability of providers in townships to establish a relationship with patients was worse than that of providers in villages.

- Policy officials and medical educators must focus on systemically reforming medical school curricula and integrating evidence-based communication skills training rather than simply encouraging further education using an outdated curriculum.

- Appropriate incentives should be provided to encourage rural providers and improve their job satisfaction.

- It is necessary to enhance the ability of providers in townships to communicate with strangers.

Introduction

A wealth of literature has demonstrated the

importance of providers’ communication skills

to the delivery of high-quality healthcare.1 2

Although definitions of effective provider-patient

communication vary, some common attributes are as follows: establish a provider-patient relationship,

elicit and understand patient perspectives, convey

empathy and affirmation, and reach shared decisions

regarding treatment and goals.2 3 Effective provider-patient

communication has been shown to improve

diagnoses, treatment plans, health outcomes, patient satisfaction, and treatment compliance1 2 4;

in contrast, deficiencies in provider-patient

communication are associated with patient anger,

frustration,5 and malpractice litigation.6

Measuring and improving providers’

communication skills are especially critical in

rural China’s primary healthcare facilities. As rural

residents’ first points of contact, village clinics and

township healthcare centres provide services for

a large proportion of the population in those areas

(40.42%)7 8; however, their quality of service remains

low.9 10 For example, Shi et al9 found that rural

clinicians were incorrect in 41% of their diagnoses

and gave prescriptions that were unnecessary or

harmful 64% of the time.

Existing research has reached the consensus

that quality medical care is heavily dependent

on providers’ communication skills,1 2 4 but some

prominent limitations also exist. First, to our

knowledge, no studies have measured provider-patient

communication skills in rural primary

healthcare facilities in China. Instead, existing

research has focused on medical students and related

education11 12 or examined providers in upper-tier

hospitals.13 14 15 Second, studies have primarily

relied on recall-based assessments, such as patient

exit interviews or surveys, which may be biased or

inaccurate.12 14 Finally, students and clinicians in

those studies are notified in advance that they are

being evaluated, which may lead them to deviate

from their actual clinical behaviours because they know they are being observed (also known as the

‘Hawthorne Effect’).12 13 14

Given the above, it is critically important

to understand how rural providers communicate

with their patients. The primary goal of this study

was to systematically describe and analyse the

communication skills of primary care providers in

China’s rural healthcare system and to identify the

provider- and facility-level factors of providers’

interactions with standardised patients (SPs).

Methods

Setting and study design

Stratified random sampling was employed as the

sampling method. The study sample was drawn from

rural areas in three provinces: Anhui, Eastern China;

Sichuan, Central China; and Shaanxi, Western China.

Specifically, 21 counties were randomly selected

from a total of 24 counties in the sample provinces.

Within the selected counties, 209 township health

centres and 139 village clinics were randomly

selected as the study sample (441 providers in total).

Two separate waves of data collection were

conducted among the village- and township-level

providers: an initial provider survey conducted in June

2015 and visits by SPs in August 2015. The provider

survey included items about basic demographic

characteristics, educational attainment, medical

experience, medical instruments, and the facility in

which they worked. In August 2015, SPs visited all

sampled township health centres and village clinics

with concealed devices to record their encounters.

The recordings were then transcripted with the

consultation of the SPs.

Standardised patients

A total of 63 individuals (42 male and 21 female;

mean age 36 years; range, 25-50 years) were hired

and trained as SPs in three provinces (21 from each

province). To be qualified as SPs, they had to be of

average weight and height and in good overall health

with no obvious signs of illness or other conditions

that might influence the accuracy of diagnoses.

The SPs were divided into 21 groups of three. In

each group, each SP was taught to report a case

of either pulmonary tuberculosis, childhood viral

gastroenteritis, or unstable angina. In each location,

the group of three SPs visited the township health

centre in a randomly arranged order. Only one SP was

sent to village clinics to minimise the risk that SPs

were identified as fake patients. The case reported by

SPs visiting a village clinic was randomly determined

beforehand. Upon presenting to the provider, the SPs

made an opening statement describing the primary

symptom(s) of their disease case (fever and cough

for pulmonary tuberculosis, diarrhoea for viral

gastroenteritis, or chest pain for angina). For the viral gastroenteritis cases, the SPs presented the case

of a child who was not present. The SPs responded

to all questions asked by the providers following a

predetermined script, purchased all medications

prescribed (which are sold by providers in China),

and paid the providers their fees. After each visit, the

SPs were debriefed using a structured questionnaire,

and the SPs’ responses were confirmed against a

recording of the interaction taken using a concealed

recording device.

Measuring communication skills

Over the past 10 years, China has used various

methods and tools to measure the communication

level of Chinese providers; although progress has

been made, rigorously validated and widely accepted

measurement tools are still lacking. Meanwhile,

studies in other countries have used a variety

of verified scales owing to their large amount of

research on this topic over the last 30 years. The

SEGUE Framework is one of the most common

tools used to assess providers’ communication skills.

In previous studies, the scale has demonstrated

acceptable psychometric characteristics (inter-rater

reliability, validity, and sensitivity to differences in

performance) in varied contexts.11 14 15 16

First developed by Makoul,17 the SEGUE

Framework employs a nominal (Yes/No) scale to

allow coders to assess medical communication skills

using a task-based checklist. The SEGUE checklist

contains 25 items, which are classified into the five

aforementioned dimensions as follows: (1) ‘Set the

stage’ [5 items]; (2) ‘Elicit information’ [10 items];

(3) ‘Give information’ [4 items]; (4) ‘Understand

the patient’s perspective’ [4 items]; and (5) ‘End

the encounter’ [2 items]. Each of the 25 items

comprising the SEGUE Framework can also be

coded into one of two categories: communication

content (17 items) or communication process (8

items). Communication content tasks include topics

raised or behaviours enacted at least once during

the encounter (eg, Discuss antecedent treatments).

Conversely, communication process items focus

on the manner in which providers communicate,

assessing aspects such as behaviours that should be

maintained throughout the encounter (eg, Maintain

a respectful tone).17 We used a Chinese version

of the SEGUE, which was translated to test the

communication skills of Chinese medical students.11

Eight research assistants were recruited

from the local community and trained to code the

providers’ communication skills. Following a highly

structured protocol, we conducted a series of training

sessions to ensure that the coders could understand

and accurately use the SEGUE Framework to score

various possible behaviours and interactions. The

coders then followed the transcripts while listening

to the recordings and identified the targeted behaviours contained in the SEGUE Framework

whenever they occurred. Coders were blinded to the

provider-, facility-, and regional-level characteristics

of each encounter. The overall score for all of the

different communication dimensions was computed

by adding the total scores for each dimension per

encounter. The Cronbach’s α internal consistency

reliability estimate of SEGUE Framework is 0.63.

This moderate reliability result suggests that the

SEGUE Framework is an acceptable measurement

tool.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the mean, standard deviation, and

scoring rate (the rate at which providers achieved the

SEGUE checklist items) across all SP interactions for

each of our primary outcomes: the five dimensions,

Communication content, Communication process,

and the total score across all five SEGUE dimensions.

Ordinary least squares regressions were conducted

to assess the correlates of the different dimensions

of communication skills. For each of the primary

outcomes mentioned above, we assessed the

correlations with a fixed set of provider-level and

facility-level characteristics. These included the

provider’s gender, age, education, certification,

number of patients in catchment area, number of

full-time physicians employed at the facility, distance

between the county hospital and the facility, and the

monetary value of the facility’s medical instruments.

All regressions controlled for the fixed effects of

the disease cases, the SPs, and the coders. Analyses

were conducted using Stata 14.2 (Stata Corporation;

College Station, [TX], United States).

Results

Provider and facility characteristics

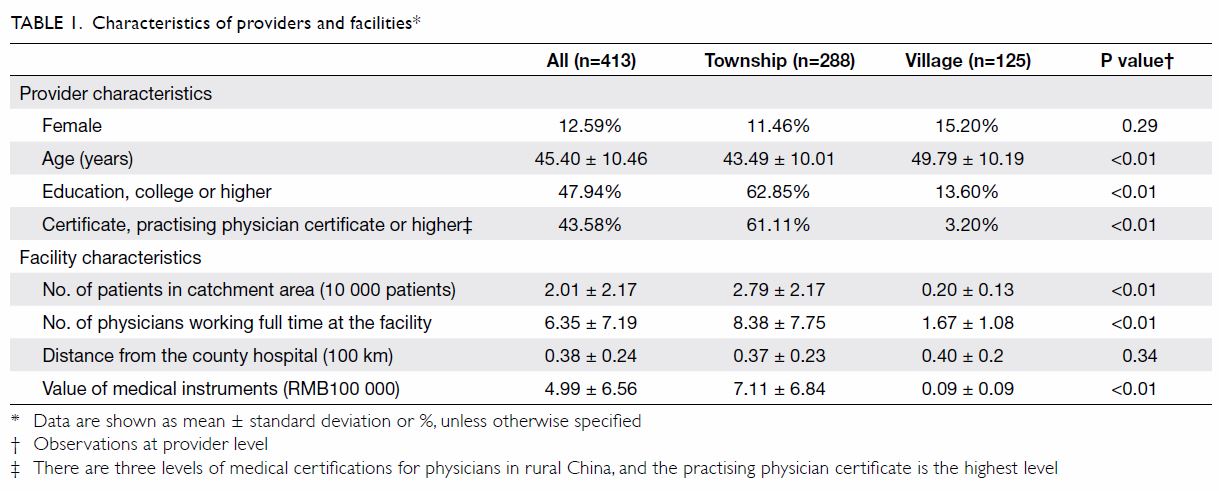

A total of 413 providers and 504 SP encounters were

included in our analysis (Table 1). The providers’

mean age was 45.40 years, and 87.4% of them were

male. A total of 47.9% of the providers had achieved

a minimum education level of college diploma, and

43.6% had a practising physician certificate, which

is the highest level of medical certification that can

be obtained by physicians in rural China. Township

health centres had a more developed and extensive

medical infrastructure than village clinics had

(P<0.01): the average value of the medical equipment

in township health centres was much higher than

that in village clinics (RMB 711 000 vs RMB 9000;

Table 1).

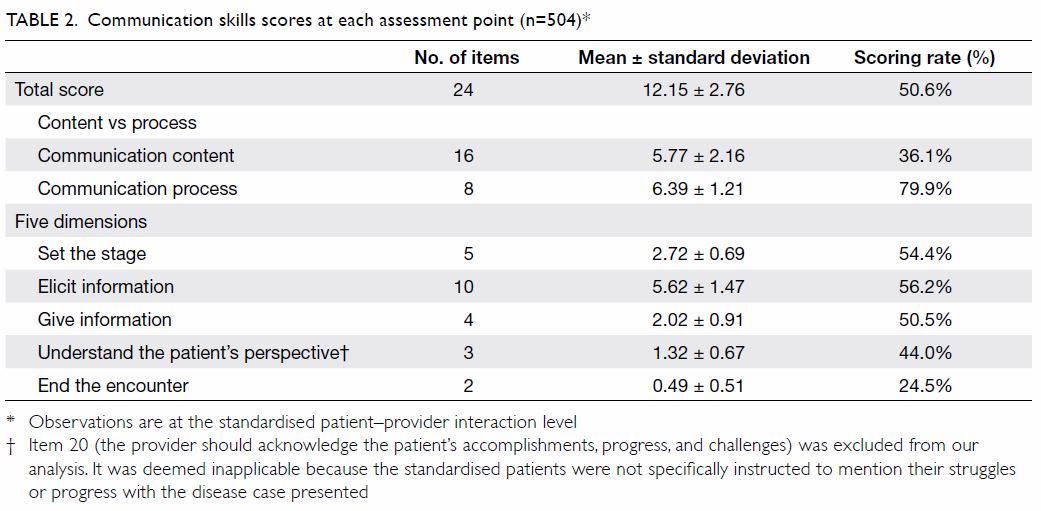

Communication skills scores

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the total

SEGUE score and each of the five SEGUE dimensions.

On average, providers scored 50.6% (12.15 of 24)

on all SEGUE communication tasks (range, 16.7%-79.2%; 4-19 of 24), indicating that providers in rural

China had relatively poor communication skills.

Moreover, the providers scored means of 36.1%

(5.77 of 16) and 79.9% (6.39 of 8) on Communication

content and Communication process, respectively.

Among the five SEGUE dimensions, the providers

had difficulty with ‘End the encounter’ and

‘Understand the patient’s perspective’, scoring

means of 24.5% (0.49 of 2) and 44.0% (1.32 of 3), but

attained relatively high mean scores of 54.4% (2.72 of

5) and 56.2% (5.62 of 10) in ‘Set the stage’ and ‘Elicit

information’, respectively.

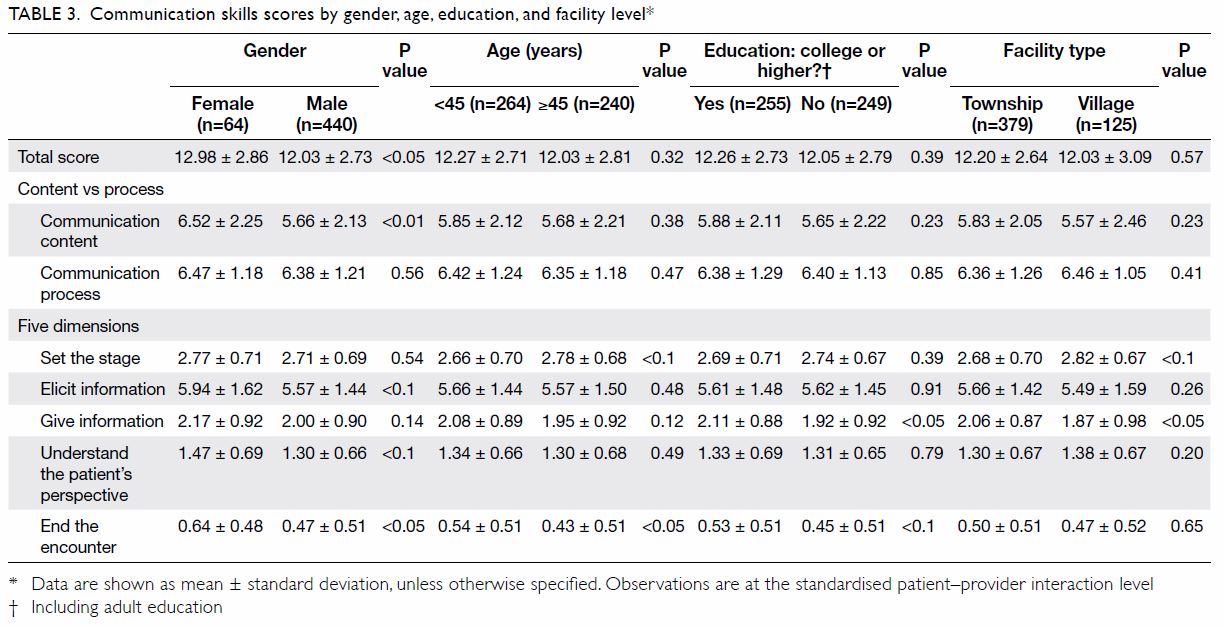

Further summary statistics of provider

communication skills are presented by gender, age,

education, and facility type in Table 3. The total

score achieved by female providers was slightly

but significantly higher than that of male providers (12.98 vs 12.03, P<0.05), which was also the case

for Communication content (6.52 vs 5.66, P<0.01),

‘Elicit information’ (5.94 vs 5.57, P<0.1), ‘Understand

the patient’s perspective’ (1.47 vs 1.30, P<0.1), and

‘End the encounter’ (0.64 vs 0.47, P<0.05). We

found statistically significant differences when

the individual SEGUE dimensions were examined

among subgroups. For instance, providers aged <45

years, who had a college education, and who were

based in township health centres performed better in

‘Give information’ and ‘End the encounter’. However,

their counterparts scored higher in ‘Set the stage’.

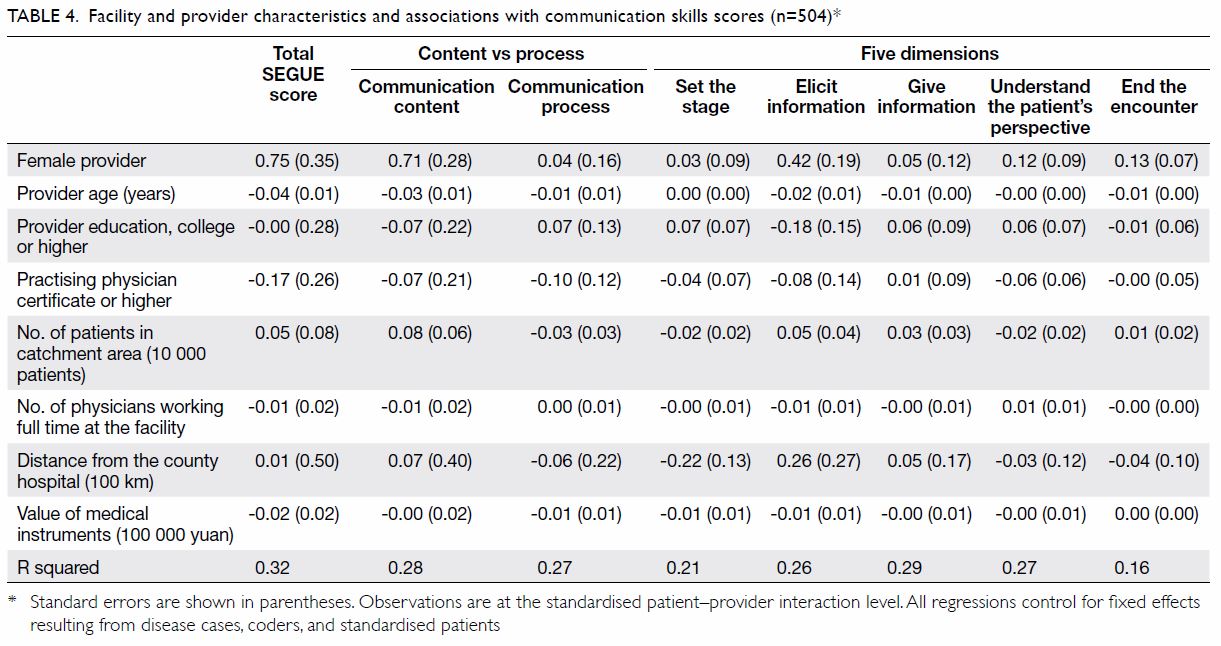

Predictors of providers’ communication

skills

Table 4 shows the results of multiple linear regressions

between the different dimensions of communication skills and provider and facility characteristics.

The provider’s gender was the factor that had the

strongest correlation with communication skills.

Female providers scored 0.75 points higher in their

total communication score (P<0.05) and 0.71 points

higher in the aspect of Communication content

(P<0.05) than their male counterparts. Among the five different dimensions of interaction that were

examined, female providers mainly excelled in their

ability to ‘Elicit information’, scoring about 0.42

points higher than male providers did (P<0.05). In

addition to provider gender, provider age was also

significantly correlated with communication skills.

Younger providers scored 0.04 points higher than their older counterparts on total SEGUE

score (P<0.01). Younger providers were more likely to score

higher in three of the five SEGUE dimensions:

‘Elicit information’, ‘Give information’, and ‘End the

encounter’. The results of the regressions without

correction for fixed effects are shown in the online

supplementary Appendix.

Table 4. Facility and provider characteristics and associations with communication skills scores (n=504)

Discussion

The results revealed that rural providers in China

had relatively poor communication skills overall,

especially in terms of understanding patients, caring

for them, and inviting patients to participate in

the interaction. Female and younger providers had

significantly higher overall communication scores,

even after controlling for fixed effects of SPs, disease

cases, and coders.

We found that rural providers in China had

relatively poor communication skills overall. They

performed poorly at most tasks involving patient

engagement during the encounter, such as inviting

them to discuss their questions and concerns.

In these cases, patients generally adopt a more

passive role, which could lead to inaccuracies

and inefficiencies when providers do not elicit

all information necessary to develop an effective

diagnosis and treatment plan.18 Moreover, while

rural providers generally maintained a respectful

tone throughout their patient encounters, they

seldom actively expressed understanding, care, or

concern.

Two possible explanations may account for the

rural providers’ poor communication skills. First, in

the past, medical students (ranging from those in-service

to those engaged in continuing education)

rarely received instruction in provider-patient

communication.19 20 21 According to a 2015 survey of

81 independent medical colleges, the proportion

of medical students who took provider-patient

communication courses was 61%, and the percentage

required to take compulsory communication

courses was only 27%.20 Thus, most currently

practising occupational health technicians have not

received systematic education in provider-patient

communication at an academic level.22 Training for

rural providers is more concerned with clinical skills

and medication knowledge and does not generally

involve provider-patient communication.23 This gap

has caused rural clinicians to have an insufficient

understanding of the importance of communication,

and their interpersonal abilities tend to be relatively

weak. Indeed, our data revealed no correlation

between education level and communication skills,

suggesting that further education does not improve

the providers’ methods of interacting with their

patients (Tables 3 and 4). Second, rural providers

have heavy workloads but low incomes compared with urban providers.24 25 Thus, they sometimes lack

enthusiasm for their work, are unwilling to give

patients humane care, and lack the motivation to

improve their communication skills.26 27 According

to survey data from providers in Chinese township

hospitals, income and provider-patient relationship

quality have positive impacts on rural providers’ job

satisfaction, and the provider-patient relationship

has strong endogeneity.28

Compared with the providers in townships,

the providers at village clinics were more likely to

make personal connections with their patients and

established a warmer and more accessible clinic

environment during the encounters. This result is

unsurprising, as township health centres serve a

patient population that is 13 times that of village

clinics (Table 1). Consequently, providers in villages

are more likely to develop longitudinal relationships

with their local patients and communities,

enabling greater knowledge of villagers’

socioeconomic backgrounds and more personable

communication.24 29

Our study also found that the providers’ gender

was associated with their level of communication

skills, especially in gathering information and

reviewing the next steps with patients. These results

are in line with a large body of literature that links

female gender with greater provider engagement

in patient concerns and asking more psychosocial

questions.30 31 These behaviours may stimulate

greater patient disclosure of aspects that are both

psychosocial and biomedical in nature. Thus,

although male and female providers did not differ

in the amount of information they provided to their

patients, the patients of female physicians collected

more biomedical information than those of male

providers.

Moreover, we found that younger providers

performed well in the two dimensions that are

directly related to diseases: eliciting or sharing

information, and reviewing the next steps with

patients. We conclude that greater experience may

not necessarily help providers to develop better

communication skills. One possible explanation is

that low income, heavy workload, lack of appreciation,

and restrictions on providers’ autonomy imposed

by hospital guidelines may contribute to fading

enthusiasm and burnout.32 33 Burnout may influence

the quality of care, resulting in more suboptimal

and less compassionate care.34 Older providers

who have been in their roles for longer periods are

more likely to experience emotional exhaustion.35

Therefore, although older providers have more

experience communicating with patients, they

do not necessarily communicate better. This is

consistent with previous findings indicating that

communication skill does not automatically develop

over time or with experience.36 37

Our study has three main limitations. First,

we evaluated providers’ communication skills

using audio recordings from concealed devices

rather than videos, which may have resulted in an

underestimation of providers’ communication skills

due to our sole reliance on verbal communication.

Second, although unannounced SPs may capture

actual provider behaviour more accurately, the

SPs themselves may not have accurately mimicked

actual patients, as they did not initially offer disease-related

information unless the providers asked for

it. However, any effects caused by the simulated

environment did not impact the comparisons

between different types of providers. We also

increased the accuracy of our observation of the

providers’ communication behaviour by excluding

any influence of the patient’s communication ability

on the provider. Finally, the physician-patient

relationship in the Asian context has historically been

described as more paternalistic than that in Western

countries.38 Thus, the SEGUE scale, which was based

on a Western model, may not be completely suitable

for measuring Chinese providers’ communication

skills. However, as increasing numbers of patients

and providers are recognising the importance of

‘patient-centred’ communication,21 39 the SEGUE

Framework is an effective tool for understanding the

characteristics of rural providers’ communication

skills in most regards.

Conclusion

The study revealed that providers in rural China have

poor communication skills overall. These deficits in

communication skills were especially pronounced

when providers were required to ‘Understand the

patient’s perspective’ and ‘End the encounter.’ They

asked about basic symptoms but rarely took the

initiative to invite patients to participate in the

encounter or discuss their questions and concerns,

and they also rarely showed care for the patients

themselves. Moreover, we found that the providers

from village clinics were more likely to make personal

connections with their patients. Female and younger

providers exhibited better communication skills,

asked more follow-up questions, and explained

future plans and steps more frequently than their

male and older counterparts.

Author contributions

Concept or design: Q Zhou, J Yang, J Nie, H Xue.

Acquisition of data: Q Zhou, Q An, N Wang, J Li, Q Gao, H Xue.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Q Zhou, J Li, Y Gao, J Yang, J Nie, H Xue.

Drafting of the manuscript: Q Zhou, J Yang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: Q Zhou, Q An, N Wang, J Li, Q Gao, H Xue.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Q Zhou, J Li, Y Gao, J Yang, J Nie, H Xue.

Drafting of the manuscript: Q Zhou, J Yang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the standardised patients and coders for their hard work.

Funding/support

The authors are supported by the 111 Project (Grant No.

B16031), Laboratory of Modern Teaching Technology of the

Ministry of Education, Shaanxi Normal University, National

Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71703083),

the National Social Science Fund Youth Project (Grant No.

15CJL005), the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (Grant No. 71703084), and the Knowledge for Change

Program at The World Bank (Grant No. 7172469).

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Stanford University, United States (Protocol no. 25904) and

Sichuan University, China (Protocol no. K2015025).

References

1. Orth JE, Stiles WB, Scherwitz L, Hennrikus D, Vallbona

C. Patient exposition and provider explanation in routine

interviews and hypertensive patients’ blood pressure

control. Health Psychol 1987;6:29-42. Crossref

2. Ward MM, Sundaramurthy S, Lotstein D, Bush TM,

Neuwelt CM, Street RL Jr. Participatory patient-physician

communication and morbidity in patients with systemic

lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:810-8. Crossref

3. Mafinejad MK, Rastegarpanah M, Moosavi F, Shirazi

M. Training and validation of standardized patients

for assessing communication and counseling skills of

pharmacy students: a pilot study. J Res Pharm Pract

2017;6:83-8. Crossref

4. Henman MJ, Butow PN, Brown RF, Boyle F, Tattersall

MH. Lay constructions of decision-making in cancer.

Psychooncology 2002;11:295-306. Crossref

5. van Osch M, van Dulmen S, van Vliet L, Bensing J.

Specifying the effects of physician’s communication on

patients’ outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. Patient

Educ Couns 2017;100:1482-9. Crossref

6. Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM.

Physician-patient communication. The relationship with

malpractice claims among primary care physicians and

surgeons. JAMA 1997;277:553-9. Crossref

7. Babiarz KS, Miller G, Yi H, Zhang L, Rozelle S. China’s

new cooperative medical scheme improved finances of

township health centers but not the number of patients

served. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1065-74. Crossref

8. National Bureau of Statistics, PRC Government. National

Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Available from: http://www.

stats.gov.cn/. Accessed 7 Jun 2019.

9. Shi Y, Xue H, Wang H, Sylvia S, Medina A, Rozelle S.

Measuring the quality of doctors’ health care in rural

China: an empirical research using standardized patients

[in Chinese]. Studies in Labor Econ 2016;4:48-71.

10. Xue H, Shi Y, Huang L, et al. Diagnostic ability and

inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions: a quasi-experimental

study of primary care providers in rural China. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019;74:256-63. Crossref

11. Li J. Using the SEGUE Framework to assess Chinese

medical students’ communication skills in history-taking

[in Chinese]. Dissertation. China Medical University.

2008. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/

detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD2008&filena

me=2008082494.nh. Accessed 7 Jun 2019.

12. Li H, Li D, Wang J, et al. Assessment on doctor-patient

communication skills of medical students with SEGUE

framework scale [in Chinese]. Hospital Manage Forum

2016;33:29-30.

13. Xu T, Dong E, Liu W, Liang Y, Bao Y. Reliability and validity

of the Chinese version of the Liverpool Communication

Skills Assessment Scale [in Chinese]. Chin Mental Health J

2013;27:829-33. Crossref

14. Shen L, Sun G. Assessment pf physician-patient

communication skills in practicing physicians by SEGUE

framework [in Chinese]. Chin Gen Pract 2017;20:1998-

2002.

15. Zhao T, Zou X, Zhou H, Ma H. General practitioner-patient

communications in outpatient clinic settings in

Beijing [in Chinese]. Chin Gen Pract 2019;22:413-6.

16. Makoul G. The SEGUE Framework for teaching and

assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns

2001;45:23-34. Crossref

17. Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in

medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement.

Acad Med 2001;76:390-3. Crossref

18. Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behavior

on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:692-6. Crossref

19. Li S, Liu Y. The achievements, problems and experiences

of the health services development in China’s 30-year

reform and opening-up [in Chinese]. Chin J Health Policy

2008;1:3-8.

20. Liu H, Shen C. Investigation report on educational

organization status of humanistic medicine in independent

medical universities [in Chinese]. Med Philos (A)

2015;36:13-8, 50.

21. Liu X, Rohrer W, Luo A, Fang Z, He T, Xie W. Doctorpatient

communication skills training in mainland China:

a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns

2015;98:3-14. Crossref

22. Guo L, Wang H, Zeng Q, et al. Exploration and practice of

the ways of cultivating communication and communication

ability of rural doctors [in Chinese]. Chin Rural Health

Serv Adm 2011;31:1017-8.

23. Song J, Yin W, Feng Z, et al. A study on-job-training status

and demand of rural doctors in Shandong Province [in

Chinese]. Chin Health Serv Manage 2017;34:378-80.

24. Hung LM, Shi L, Wang H, Nie X, Meng Q. Chinese primary

care providers and motivating factors on performance.

Fam Pract 2013;30:576-86. Crossref

25. Xue H, Shi Y, Medina A. Who are rural China’s village clinicians? Chin Agric Econ Rev 2016;8:662-76. Crossref

26. Campbell N, McAllister L, Eley D. The influence of

motivation in recruitment and retention of rural and

remote allied health professionals: a literature review.

Rural Remote Health 2012;12:1900.

27. Sun K, Yin W, Huang D, Yu Q, Zhao Y, Li Y. The effect of

income on occupation mentality of rural doctors under the

situation of new medical reform. Chin Health Serv Manage

2016;33:371-3.

28. Dong X, Ariana P. Why are rural doctors not satisfied with

their work? An empirical study on job income, doctorpatient

relationship and job satisfaction. Manage World

2012;(11):77-88.

29. Haddad S, Fournier P, Machouf N, Yatara F. What does

quality mean to lay people? Community perceptions

of primary health care services in Guinea. Soc Sci Med

1998;47:381-94. Crossref

30. Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered

communication: a critical review of empirical research.

Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:497-519. Crossref

31. Swygert KA, Cuddy MM, van Zanten M, Haist SA, Jobe

AC. Gender differences in examinee performance on the

Step 2 Clinical Skills data gathering (DG) and patient note

(PN) components. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract

2012;17:557-71. Crossref

32. Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the

third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in

medical school. Acad Med 2009;84:1182-91. Crossref

33. Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and

career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol

2014;32:678-86. Crossref

34. Dyrbye LN, Massie FS Jr, Eacker A, et al. Relationship

between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes

among US medical students. JAMA 2010;304:1173-80. Crossref

35. Yin S, Zhao J, Chen R. Empathy fatigue of clinical doctors

and its influencing factors. Chin Gen Pract 2016;19:206-9.

36. Kosunen E. Teaching a patient-centred approach and

communication skills needs to be extended to clinical

and postgraduate training: a challenge to general practice.

Scandi J Prim Health Care 2008;26:1-2. Crossref

37. Skoglund K, Holmström IK, Sundler AJ, Hammar LM.

Previous work experience and age do not affect final

semester nursing student self-efficacy in communication

skills. Nurse Educ Today 2018;68:182-7. Crossref

38. Ishikawa H, Takayama T, Yamazaki Y, Seki Y, Katsumata

N, Aoki Y. The interaction between physician and patient

communication behaviors in Japanese cancer consultations

and the influence of personal and consultation

characteristics. Patient Educ Couns 2002;46:277-85. Crossref

39. Ting X, Yong B, Yin L, Mi T. Patient perception and the

barriers to practicing patient-centered communication:

a survey and in-depth interview of Chinese patients and

physicians. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:364-9. Crossref