Blood transfusions in total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective analysis of a multimodal patient blood management programme

Hong Kong Med J 2020 Jun;26(3):201–7 | Epub 6 May 2020

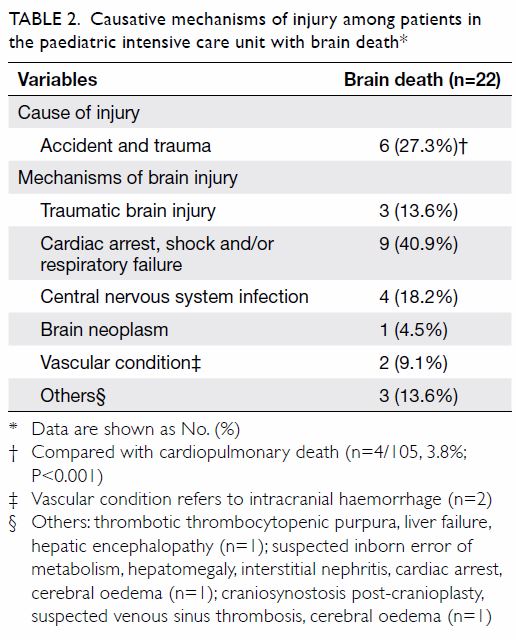

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

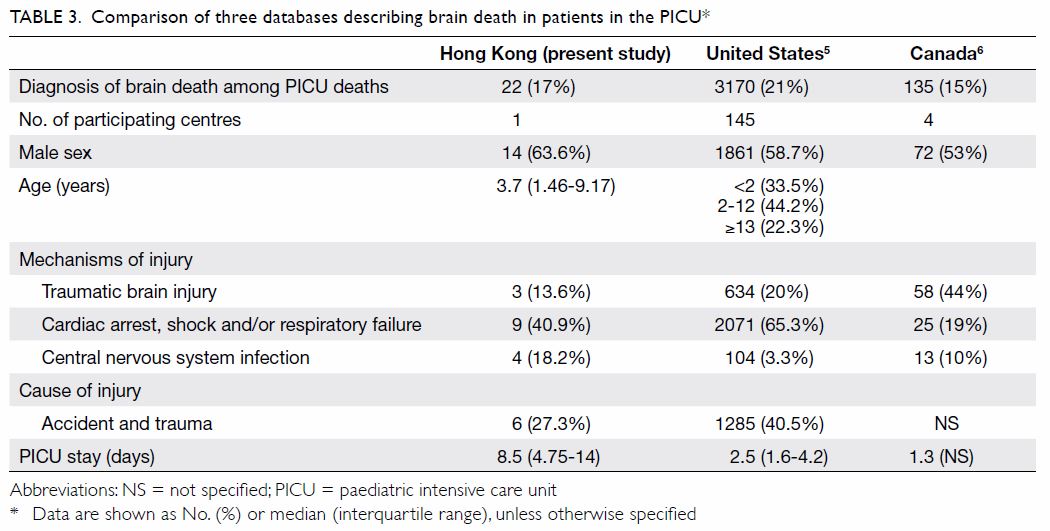

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Blood transfusions in total knee arthroplasty: a

retrospective analysis of a multimodal patient blood management programme

PK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; YY Hwang, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Amy Cheung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; CH Yan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Henry Fu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Timmy Chan, FHKCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)3; WC Fung, BSc1; MH Cheung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Vincent WK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; KY Chiu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1

1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Anaesthesiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr PK Chan (cpk464@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Purpose: Transfusion is associated with increased

perioperative morbidity and mortality in patients

undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Patient

blood management (PBM) is an evidence-based

approach to maintain blood mass via haemoglobin

maintenance, haemostasis optimisation, and blood

loss minimisation. The aim of the present study was

to assess the effectiveness of a multimodal PBM

approach in our centre.

Methods: This was a single-centre retrospective

study of patients who underwent primary TKA

in Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong in 2013 or

2018, using data from the Clinical Data Analysis and

Reporting System and a local joint registry database.

Patient demographics, preoperative haemoglobin,

length of stay, readmission, mean units of

transfusion, postoperative prosthetic joint infection,

and mortality data were compared between groups.

Results: In total, 262 and 215 patients underwent

primary TKA in 2013 and 2018, respectively. The

mean transfusion rate significantly decreased after

PBM implementation (2013: 31.3%; 2018: 1.9%,

P<0.001); length of stay after TKA also significantly

decreased (2013: 14.49±8.10 days; 2018: 8.77±10.14

days, P<0.001). However, there were no statistically

significant differences in readmission, early prosthetic joint infection, or 90-day mortality rates between the two groups.

Conclusion: Our PBM programme effectively

reduced the allogeneic blood transfusion rate

in patients undergoing TKA in our institution.

Thus, PBM should be considered in current TKA

protocols to reduce rates of transfusions and related

complications.

New knowledge added by this study

- Patient blood management effectively reduced the allogeneic blood transfusion rate in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty in our institution; it also reduced the length of stay after total knee arthroplasty.

- Patient blood management should be considered in current total knee arthroplasty protocols to reduce rates of transfusions and related complications.

- Patient blood management in total knee arthroplasty could reduce healthcare expenditures among the ageing population in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the most effective

and efficacious surgical method to improve pain and

function for patients with end-stage osteoarthritis;

however, TKA has been associated with substantial

blood loss. In addition to visible blood loss from the

surgical field and wound drainage, hidden blood

loss occurred in patients undergoing TKA, which

resulted in mean blood loss of 1.5 L.1 Therefore, perioperative blood transfusion was needed in up to

38% of patients undergoing TKA.2

Blood transfusion is not risk-free. Often, no

adverse effects are encountered by patients who

undergo blood transfusion. However, adverse effects

occasionally occur, ranging from minor allergic

reactions to blood-borne infection and potentially

fatal acute immune haemolytic reaction. With the

implementation of best international practices to warrant blood transfusion safety by the Blood

Transfusion Service in Hong Kong, the transfusion

risk has significantly decreased in the past two

decades.3 However, absolute safety in transfusion

cannot be achieved because of the window period

for detecting infections, possibility of emerging

infections, and potential human errors related to the

process of transferring collected blood from donors

to transfusion recipients. Notably, researchers in

Hong Kong reported the first two cases (worldwide)

of transmission of Japanese encephalitis virus,

via blood transfusion to immunocompromised

hosts, in 2018.4 In addition to the general risks

associated with transfusion, blood transfusion has

been independently associated with poor surgical

outcome. Specifically, patients who underwent

transfusion exhibited an eight-fold to 10-fold excess

risk of adverse outcomes, defined as postoperative

complications in the American College of Surgeons

National Surgical Quality Improvement Project.5

With respect to total hip or knee arthroplasty, a

dose-dependent relationship between transfusion

and risk of surgical site infection was observed.6

With increasing understanding regarding the

benefits and risks of blood transfusion, as well as

alternative approaches for patients who experience

blood loss, the concept of patient blood management

(PBM) was developed. The World Health

Organization defines PBM as ‘a patient-focused,

evidence-based and systematic approach to optimise

the management of patients and transfusion of blood products for quality and effective patient care. It is

designed to improve patient outcomes through the

safe and rational use of blood and blood products

and by minimising unnecessary exposure to blood

products…’.7 The three major components of PBM

are as follows: (1) optimisation of the patient’s own

blood mass; (2) minimisation of blood loss; and (3)

optimisation of physiological tolerance to anaemia.8

This new standard of care is now well-established

in some centres in the US, Austria, and Western

Australia, as well as nationally in the Netherlands.

However, PBM remains an uncommon practice in

Asia.

We introduced the PBM programme for

patients undergoing TKA in our institution,

beginning in 2014. Various components were

introduced gradually (in phases) from 2014 to 2018.

The key measures of PBM in preoperative, intra-operative,

and postoperative periods were fully

implemented in 2018. To the best of our knowledge,

our PBM programme is a pioneer PBM programme

in Hong Kong. The aim of the present study was

to assess the effectiveness of the multimodal PBM

approach in our university-based centre.

Methods

This single-centre retrospective study was approved

by the Institutional Review Board of the University

of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West

Cluster (Ref UW 19-600). The requirement for

patient consent was waived by the review board.

We retrospectively collected blood transfusion

data regarding patients who underwent unilateral

primary TKA in our centre from 1 January 2013 to

31 December 2018. Patients who underwent one-stage

bilateral primary TKA or revision TKA were

excluded from our study. Patients with acquired or

congenital coagulopathy, as well as those currently

taking anticoagulants, were included in our study;

notably, these patients were at greater risk of

perioperative blood loss and transfusion.

The primary outcome measure was the mean

yearly transfusion rate, which was defined as the

number of patients who received transfusion after

TKA (during the same hospitalisation episode)

divided by the number of patients who underwent

TKA during the period from 1 January to 31

December; this result was multiplied by 100. The

mean units of blood given per transfusion episode

in 1 year was defined as the cumulative total number

of blood units transfused to patients after TKA in 1

year divided by the number of transfusion episodes

in that year. Transfusion data were retrieved from

the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System,

a database developed by the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority for research purposes; this database

contains medical information recorded by the Hong

Kong Hospital Authority since 1993.

Secondary outcome measures were mean

length of hospital stay after surgery, the rate of

unexpected readmission through the Emergency

Department after discharge from the hospital, the

proportion of patients who had early prosthetic

joint infection requiring revision surgery within 90

days after index surgery, and the 90-day mortality

rate. These data and other patient demographic data

(eg, age and sex), perioperative data (eg, American

Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] physical status),

and preoperative haemoglobin level were retrieved

from our patient records, as well as a local joint

replacement registry.

Patient blood management was a relatively new

concept in Hong Kong when it was first implemented

in our institution in 2014. Initially, this programme

was a standalone surgeon-initiated programme

without external support; it was implemented in

sequential stages based on PBM guidelines provided

by the National Blood Authority in Australia.9

The sequential stages of PBM implementation

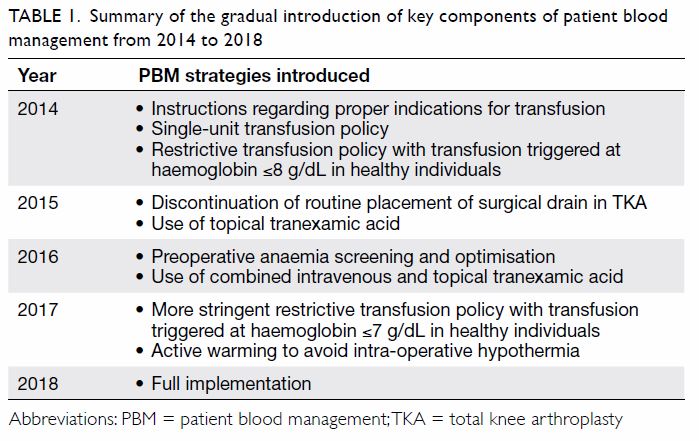

in our centre are described in Table 1. The PBM

strategies included modern surgical, anaesthetic,

and perioperative care. In 2014, PBM was initiated

with instructions regarding proper indications

for transfusion, single-unit transfusion policy,10

and restrictive transfusion policy with transfusion

triggered at haemoglobin ≤8 g/dL in healthy

individuals.11 In 2015, the traditional practice of

routine placement of a surgical drain during TKA

(associated with a higher transfusion rate12) was

stopped; the use of topical tranexamic acid (injection

of 1 g tranexamic acid into knee joint at the end of the

surgical procedure, shown to reduce postoperative

blood loss and transfusion rate13) was implemented

to reduce perioperative blood loss. In 2016,

preoperative anaemia screening and optimisation

were initiated via collaboration with haematologists.

Patients with preoperative haemoglobin <11 g/dL

were examined for causes of anaemia, in accordance

with Network for Advancement of Transfusion

Alternatives guidelines14; their erythropoiesis

and preoperative haemoglobin characteristics

were optimised before TKA was performed. For

example, patients with iron-deficiency anaemia

were checked for gastrointestinal blood loss and

prescribed iron supplementation; their haemoglobin

levels were rechecked after supplementation to

confirm achievement of ≥11 g/dL before TKA.

To further reduce intra-operative blood loss,

combined intravenous tranexamic acid (15 mg/kg

administered intravenously at the induction of

anaesthesia) and topical tranexamic acid were

implemented; these are reportedly effective for

reduction of blood loss.15 In 2017, a more stringent

restrictive transfusion policy was adopted with

transfusion triggered at haemoglobin ≤7 g/dL in

healthy individuals. Moreover, active warming (a modern anaesthetic technique used during intra-operative

care) was implemented to avoid intra-operative

hypothermia16; this hypothermia has been

associated with greater volume of blood loss and the

need for transfusion.17 18 By the beginning of 2018, all

above PBM strategies were fully implemented.

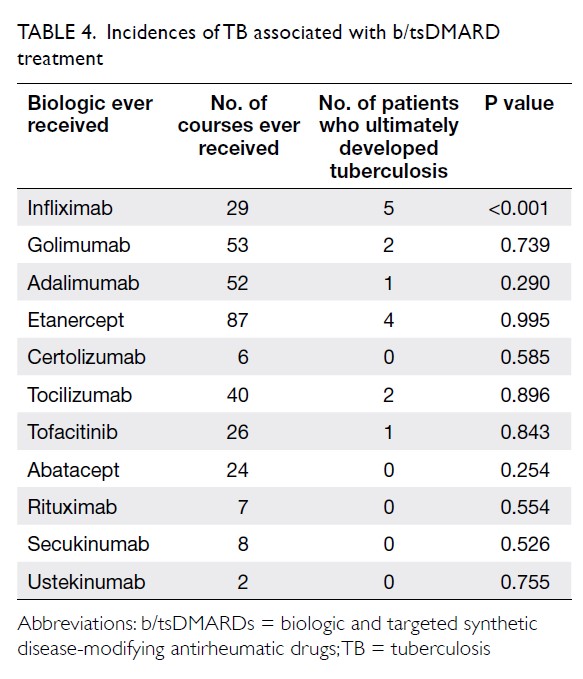

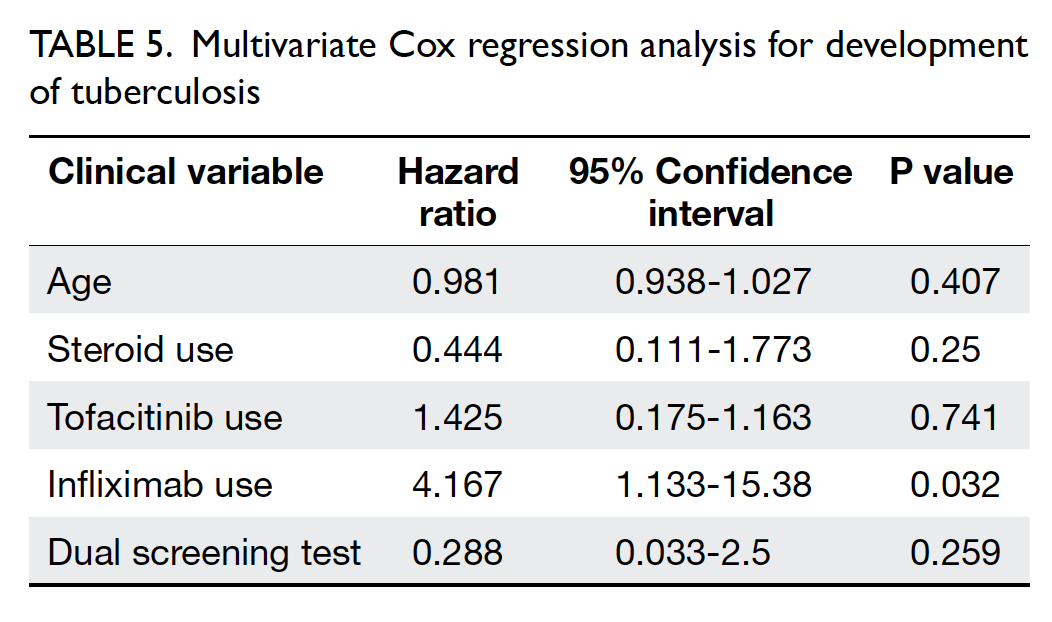

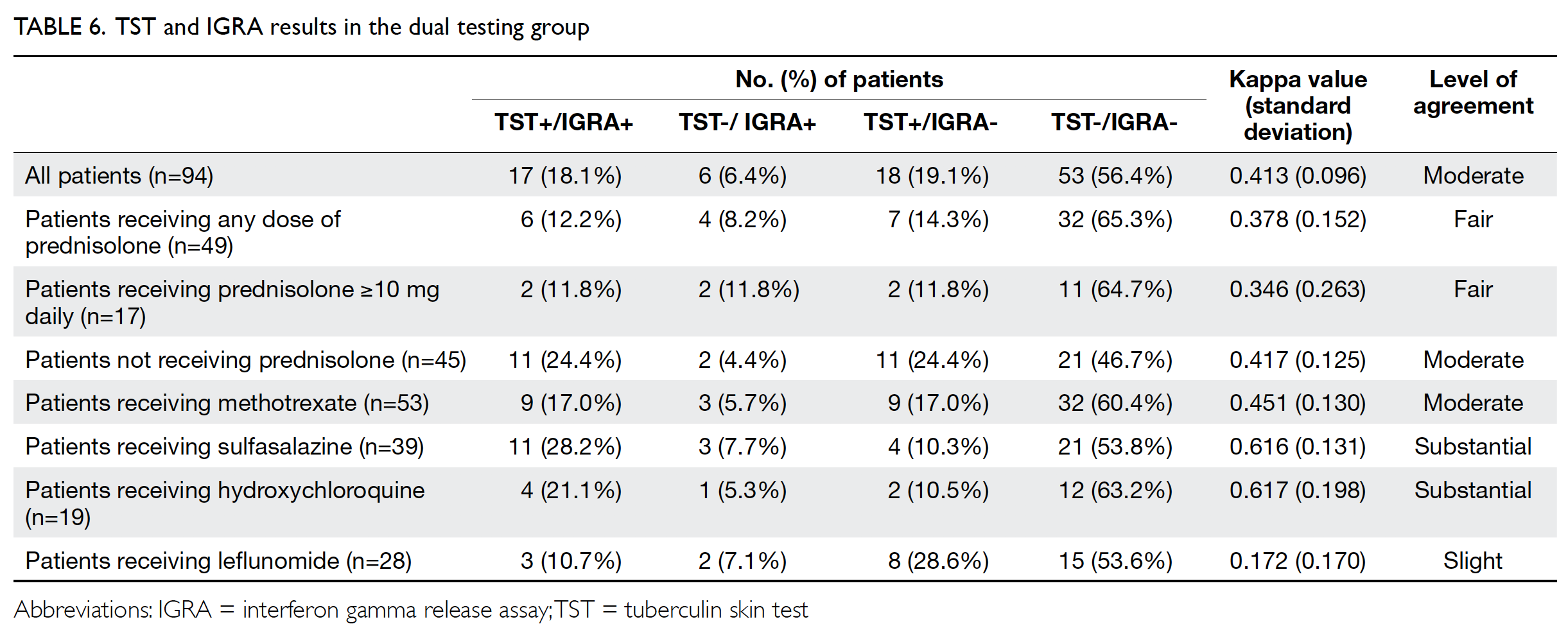

Table 1. Summary of the gradual introduction of key components of patient blood management from 2014 to 2018

In addition to PBM strategies, other changes

in patient selection and perioperative management

were implemented between 2013 and 2018. First, the

degree of medical co-morbidities may have differed

because of the establishment of another joint

replacement centre in July 2016; this new centre

provided joint replacement surgeries for patients

with improved medical fitness, among patients with

end-stage osteoarthritis in our hospital. Therefore,

the medical co-morbidities of the patients in 2013

and 2018 were compared on the basis of ASA status.

Second, because of technological advances in the

design of TKA prostheses over time, there were

differences in the numbers of modern-design TKA

prostheses between 2013 and 2018; these modern-design

TKA prostheses aimed to improve knee

kinematics, rather than reduce transfusion rate.

However, these prostheses were unlikely to bias

our transfusion rate results, according to a prior

assessment of factors predictive of transfusion rate

in patients undergoing TKA.19

In 2013, no PBM strategies had been

implemented in our institution, whereas all strategies

had been fully implemented by 2018. The Chi

squared test was used to compare the transfusion

rate between patients who underwent TKA in 2013

and those who underwent TKA in 2018; differences

with P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

As mentioned above, medical co-morbidities of the

patients in 2013 and 2018 were compared on the

basis of ASA status.

Results

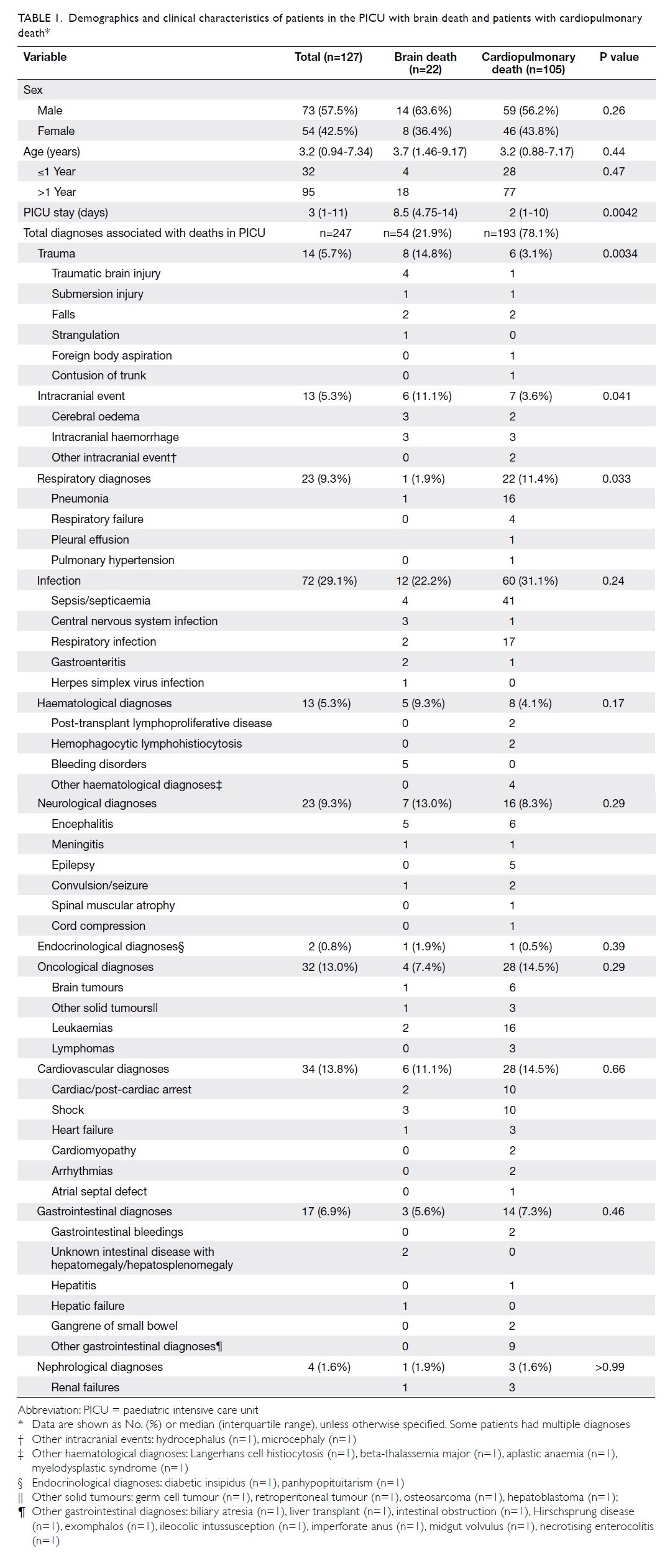

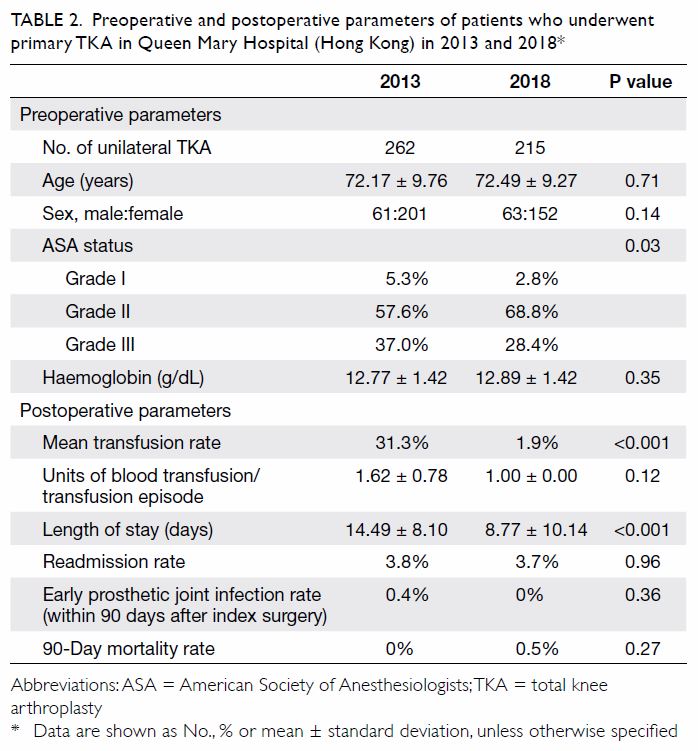

In total, 262 and 215 patients underwent primary

TKA in our centre in 2013 and 2018, respectively

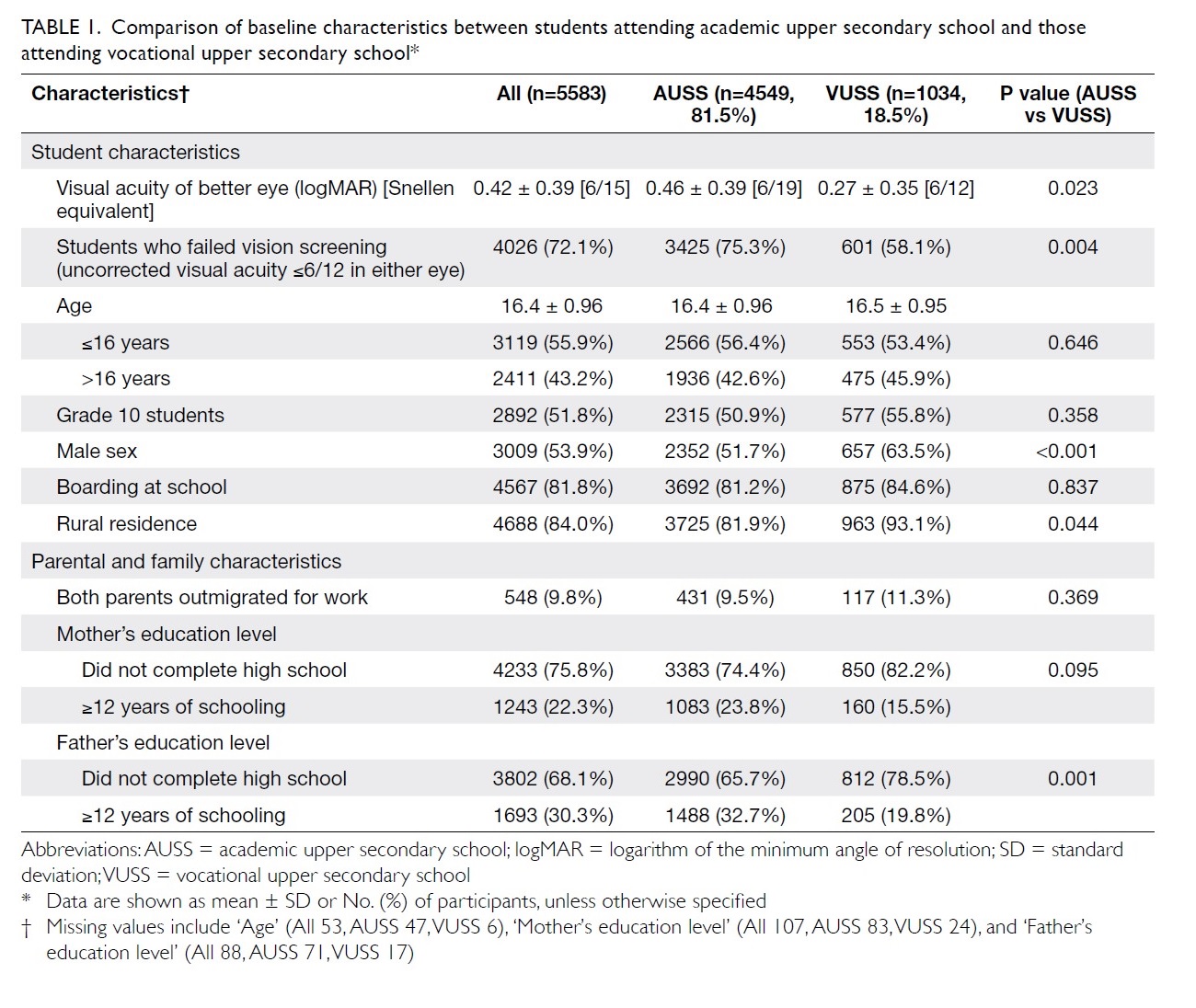

(Table 2). There were no significant differences in

mean age (2013: 72.17±9.76 years; 2018: 72.49±9.27

years, P=0.71) or sex (male:female) ratio (2013, 61:201; 2018, 63:152, P=0.14) between the groups. The

preoperative haemoglobin level was also similar

between the groups (2013: 12.77±1.42 g/dL;

2018: 12.89±1.42 g/dL, P=0.35). However, there was

a significant difference in ASA distribution between

the groups (P=0.03). There was a comparatively

greater proportion of patients with ASA Grade II

status in 2018 (2013: 57.6%; 2018: 68.8%).

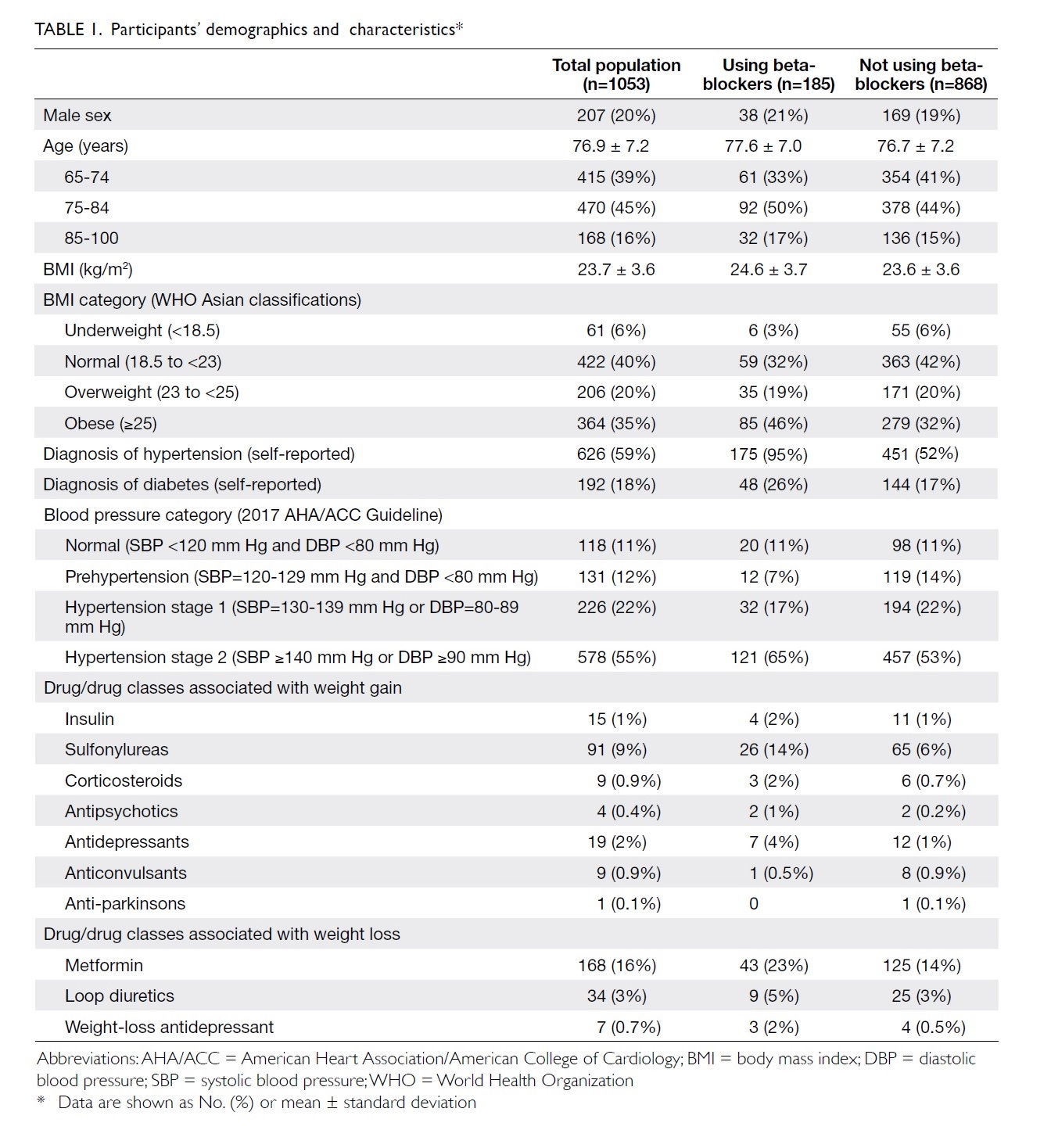

Table 2. Preoperative and postoperative parameters of patients who underwent primary TKA in Queen Mary Hospital (Hong Kong) in 2013 and 2018

The primary outcome was the mean transfusion

rate in 1 year. There was a significant difference in the

mean transfusion rate after primary TKA between

2013 and 2018 (2013: 31.3%; 2018: 1.9%, P<0.001);

however, there was no significant difference in the

mean units of blood transfused per transfusion

episode (2013: 1.62±0.78; 2018: 1.00±0.00, P=0.12).

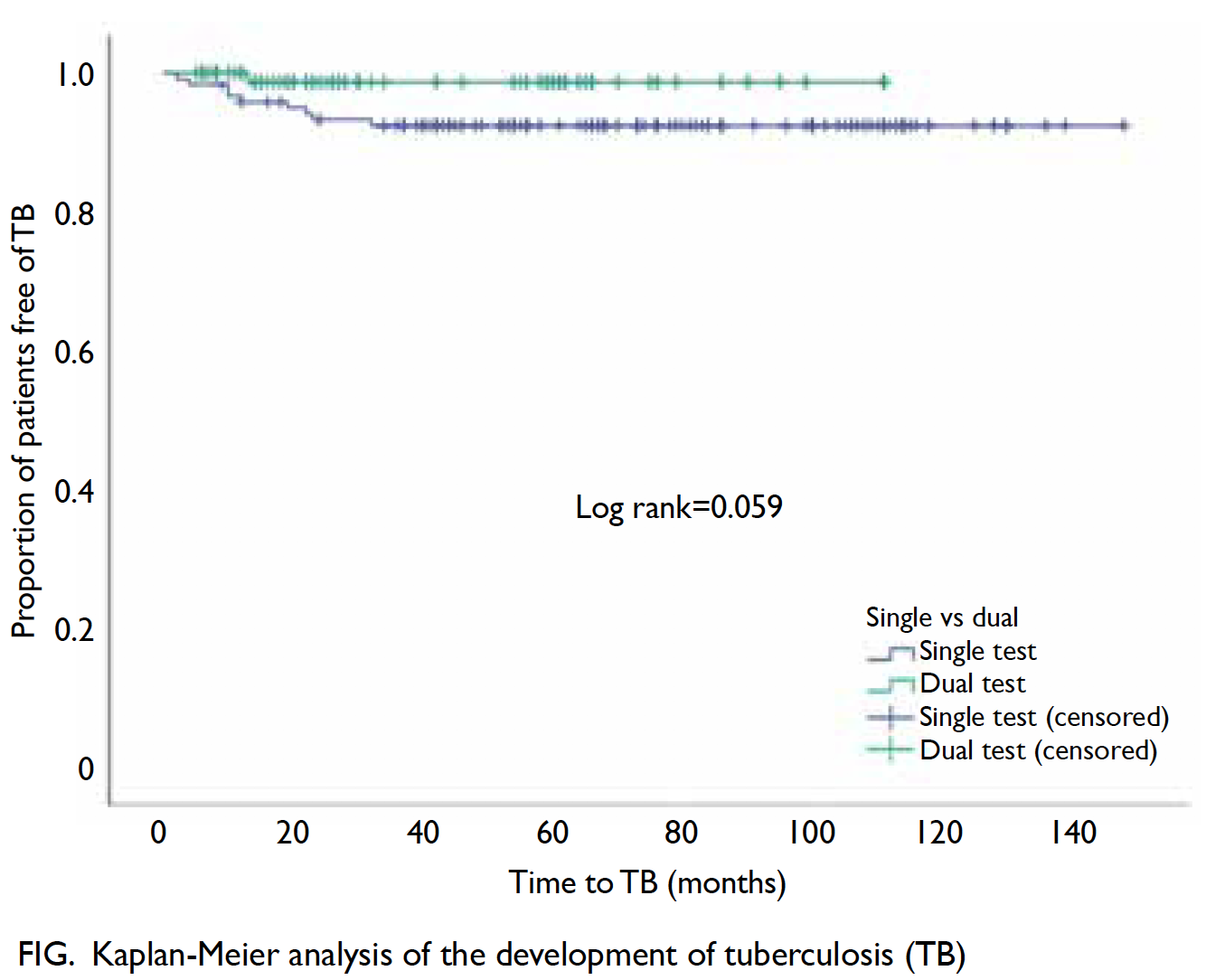

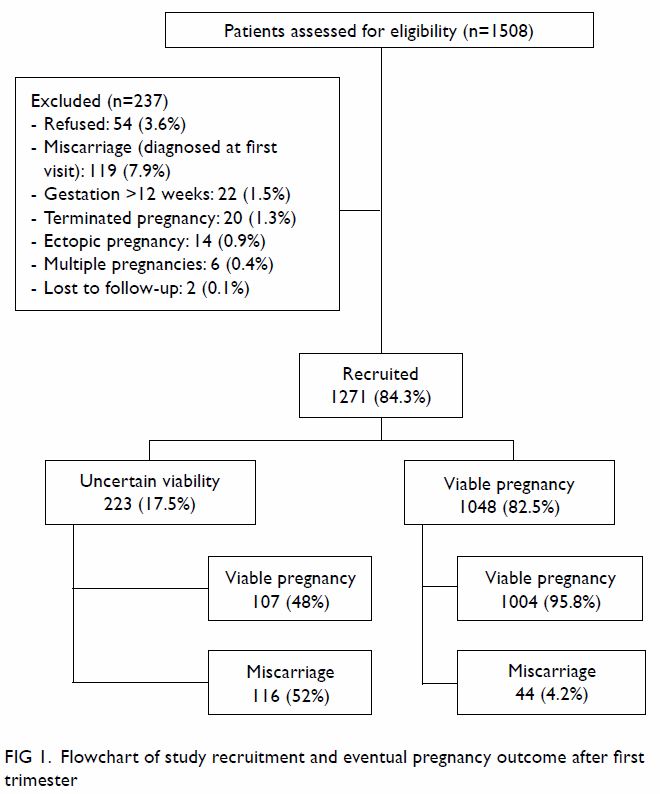

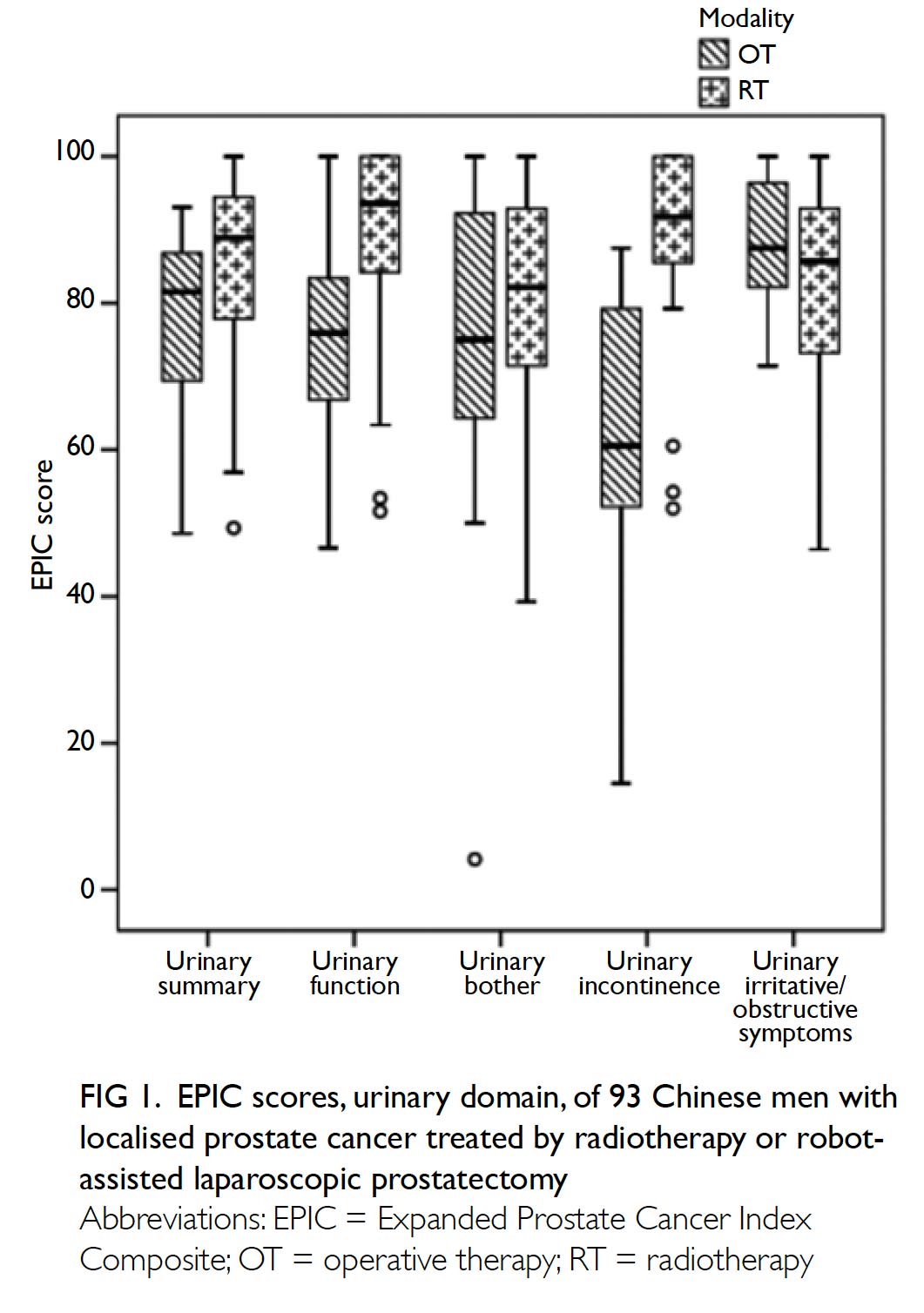

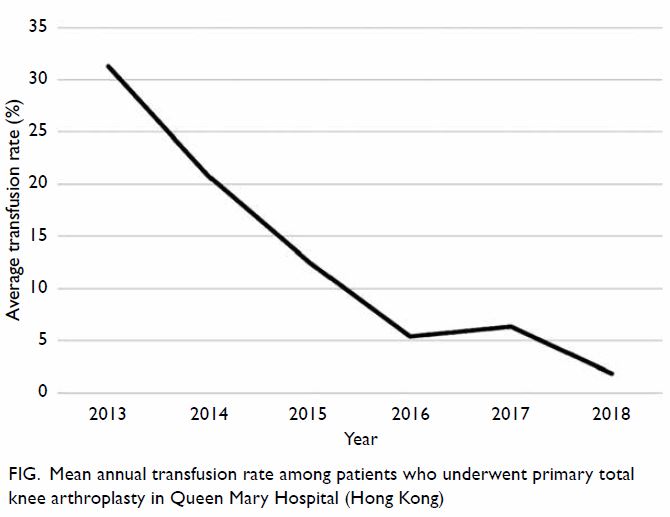

Moreover, the mean annual transfusion rate after

primary TKA exhibited stepwise reduction as PBM

strategies were implemented during the period from

2014 to 2018 (Fig).

Regarding secondary outcomes, the mean

length of hospitalisation was significantly lower

in 2018 (2013: 14.49±8.10 days; 2018: 8.77±10.14

days, P<0.001). However, there was no difference

in the unexpected readmission rate through the

Emergency Department (2013: 3.8%; 2018: 3.7%,

P=0.96), the proportion of patients who exhibited

early prosthetic joint infection within 90 days after

index surgery (2013: 0.4%; 2018: 0%, P=0.36), or the

proportion of patients with 90-day mortality (2013:

0%; 2018: 0.5%, P=0.27).

Discussion

Blood transfusion is a life-saving therapy, but is a limited resource. In recent years, there have been

recurrent blood shortages in Hong Kong, and the

Hong Kong Red Cross has issued an urgent appeal for

blood donors on several occasions.20 21 22 23 The amount of

blood stored in blood banks is determined by supply

and demand. To increase blood supply, additional

blood donors are needed. The Annual Report of Hong

Kong Red Cross in 2018/2019 revealed that 4% of

blood donors were aged >60 years, and the largest

group of blood donors were aged 41-50 years (23.7%

of donors).24 With the increasing number of older

people in Hong Kong, more blood donors are needed

from older age-groups. In addition, healthcare

professionals should be judicious in prescribing

transfusion, and should consider methods to

minimise transfusion. Our study demonstrated the

effectiveness of implementing PBM in our centre. In

addition to comparing the mean transfusion rate in

2013 and 2018, this study included an audit of the

mean annual transfusion rate after primary TKA

from 2014 to 2018 (Fig).

Figure. Mean annual transfusion rate among patients who underwent primary total knee arthroplasty in Queen Mary Hospital (Hong Kong)

Globally, PBM is not a new concept. In May 2010,

the World Health Organization formally recognised

the importance of PBM and recommended its use

to the 193 member states.25 Subsequently, PBM has been successfully implemented in Western

countries, especially Australia26 and the US.27 The

Asia-Pacific PBM Expert Consensus Meeting

Working Group assessed the status of PBM in Asia.28

In Singapore, PBM was implemented nationally,

beginning in 2013. The Ministry of Health and Blood

Services Group actively promoted PBM at public

hospitals in the first few years; regular national

audits of PBM-related efforts have been performed

since 2017 to promote appropriate use of red blood

cell transfusion and implementation of preoperative

anaemia screening for elective surgeries. Patient

blood management programmes were successfully

implemented in National University Hospital and

Singapore General Hospital.28 29 In Korea, PBM was

implemented through a professional initiative by the

Korean Research Society of Transfusion Alternatives

of the Republic of Korea in 2006; the Korean Patient

Blood Management Research Group was formed to

promote greater PBM use in 2016. The efforts of the

Korean Patient Blood Management Research Group

resulted in achievement of several PBM milestones

in 2016.28 Notably, PBM was included in the Korean

Transfusion Guidelines; a new steering committee

was also formed, comprising leading physicians from

various specialties. Patient blood management was

successfully implemented in a number of Korean

hospitals, which led to a reduction in transfusion

rate.30 31 32 In Malaysia, PBM has been promoted at the

local hospital level.28 In the Department of Maternal

and Fetal Medicine at the Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah

Hospital, women at high risk of anaemia are screened

for iron deficiency anaemia in early pregnancy; iron-deficient

women are provided oral or intravenous

iron supplementation.

At our institution, PBM was first implemented

in 2014 as a surgeons’ initiative in the Division of

Joint Replacement Surgery. In addition to good

surgical techniques, good perioperative care is an

important determinant of surgical outcomes. Patient

blood management is a component of our overall

perioperative management protocol in the modern

enhanced recovery after surgery programme. With

implementation of PBM strategies and measures in

the enhanced recovery after surgery programme,

the length of hospitalisation was shortened in 2018,

compared with 2013. Despite the shorter length of

stay, there were no differences in the unexpected

readmission rate through the Emergency

Department, the proportion of patients who had

early prosthetic joint infection within 90 days after

index surgery, or the proportion of patients who had

90-day mortality.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been

few studies regarding PBM in patients undergoing

TKA in Hong Kong. In 2015, Lee et al33 reported

their pioneering experience with implementation

of PBM in patients undergoing TKA; their PBM protocols included typing and screening only for

patients with preoperative haemoglobin of <11 g/dL,

and restrictive transfusion triggered at haemoglobin

8 g/dL. When they compared outcomes before

and after introduction of the PBM programme, the

transfusion rate (before: 10.3%; after: 3.1%, P=0.046)

and cross-match rate (before: 100%; after: 3.1%,

P<0.001) both decreased. We implemented PBM in

our institution, beginning in 2014. Modern surgical,

anaesthetic, and perioperative techniques in PBM

were gradually introduced from 2014 to 2018. Our

PBM protocols are more comprehensive than those

of Lee et al, because our protocols were designed in

accordance with the PBM guidelines provided by the

National Blood Authority in Australia.9 Therefore, our

transfusion rate in TKA in 2018 decreased to 1.9%.

Prosthetic joint infection is a severe

complication in arthroplasty; affected patients often

require revision surgery. Notably, patients who

underwent treatment for prosthetic joint infection

exhibited a significant, independent risk of increased

mortality, due to the direct adverse effect of infection

and the indirect effect of poor underlying health

condition.34 In a recent meta-analysis involving

21 770 patients who underwent total hip and knee

arthroplasty, patients who received allogeneic blood

transfusion had a significantly greater risk of surgical-site

infection (pooled odds ratio: 1.71, P=0.02).35

Recently, a dose-dependent relationship was

observed between allogeneic transfusion and surgical

site infection after total hip or knee arthroplasty.6

Therefore, PBM was expected to reduce the incidence

of surgical site infection in our centre. However,

because of the relatively small sample size in our

study and the relatively low incidence of prosthetic

joint infection (approximately 1%), a difference in

the incidence of prosthetic joint infection between

2013 and 2018 could not be identified. When PBM

was fully implemented in our centre (2018), the

transfusion rate after primary TKA was 1.9%; this

was comparable to international reported values.

Specifically, when PBM strategies were implemented

in the US, the transfusion rates were approximately

4.5%.36 When PBM is implemented by high-volume

surgeons with an eight-step checklist to reduce

bleeding, the transfusion rate after TKA could be as

low as 0.0044%.37 Therefore, a transfusion rate of 0%

is achievable.

As the transfusion rate decreased in patients

undergoing TKA, there were also benefits to the

healthcare system. Blood transfusion involves many

costs associated with blood transfer from donors

to recipients (eg, collection, screening, storage,

transportation, and prescription of donated blood).

We do not have data regarding the cost of packed

red blood cells in Hong Kong; however, the cost was

estimated to be approximately 1130 USD/unit in a

study conducted in the US.36 Therefore, reduced transfusions through implementation of PBM can

result in lower healthcare expenditures, which are of

considerable importance because of the increasing

demand for TKA among the aging population in

Hong Kong.

There were some limitations in this study. First,

it was a retrospective study; thus, compliance with

PBM strategies could not be fully verified. However,

as each strategy was introduced throughout the

course of the study, there was gradual reduction in

the transfusion rate. Therefore, compliance with the

strategies was presumably optimal. Second, because

different strategies were implemented successively,

the strategies with the greatest contribution to the

reduced transfusion rate could not be identified.

Third, because this was not a prospective randomised

placebo-controlled interventional trial, a causal

relationship between PBM strategies and reduction

in transfusion rate could not be established.

However, our study provided an assessment of real-world

implementation of PBM strategies within a

large hospital; thus, it comprises pioneering research

in Hong Kong. Fourth, some potential cofounding

factors may not have been identified or controlled

in the present analysis. For example, the type of

prosthesis used was not analysed as a separate factor.

However, preoperative haemoglobin levels (the

most significant predictor of blood transfusion19)

were compared between both groups. To the best

of our knowledge, there remains minimal relevant

literature regarding the effect of TKA prosthesis on

the transfusion rate.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated the

effectiveness of PBM implementation on transfusion

rate in patients undergoing TKA. From 2014 to 2018,

there was a stepwise reduction in transfusion rate

after TKA; this was similar to findings in previously

published research. This is one of the few studies

in Hong Kong to review PBM in surgical practice.

Although we focused on patients undergoing TKA,

the principles of PBM could be useful for other

medical or surgical specialties.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting

of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr CK Lee, Chief Executive and Medical Director, Hong Kong Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, Hong

Kong, for providing advice on the patient blood management

programme. We also acknowledge and express our gratitude to the following departments of our hospital for the support in this multidisciplinary project: Nursing Division, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology; Operation Theatre Services; and Blood Transfusion Committee.

Declaration

This research has been presented in part as an oral presentation

at the Hong Kong Hospital Authority Convention 2018.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong

West Cluster (Ref UW 19-600). The requirement for patient

consent was waived by the review board.

References

1. Sehat KR, Evans R, Newman JH. How much blood is really lost in total knee arthroplasty? Correct blood loss management should take hidden loss into account. Knee 2000;7:151-5. Crossref

2. Cushner FD, Friedman RJ. Blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991;(269):98-101. Crossref

3. Lee CK. Risk minimization in transfusion transmitted infection in Hong Kong [thesis]. University of Hong Kong; 2017.

4. Cheng VC, Sridhar S, Wong SC, et al. Japanese encephalitis virus transmitted via blood transfusion, Hong Kong, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:49-57. Crossref

5. Ferraris VA, Hochstetler M, Martin JT, Mahan A, Saha SP. Blood transfusion and adverse surgical outcomes: the good and the bad. Surgery 2015;158:608-17. Crossref

6. Everhart JS, Sojka JH, Mayerson JL, Glassman AH, Scharschmidt TJ. Perioperative allogeneic red blood-cell transfusion associated with surgical site infection after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100:288-94. Crossref

7. World Health Organization. WHO Global Forum for Blood Safety: patient blood management. Available from: https://www.who.int/bloodsafety/events/gfbs_01_pbm/en/ Accessed 5 Jan 2020.

8. Isbister JP. The three-pillar matrix of patient blood management-an overview. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013;27:69-84. Crossref

9. National Blood Authority Australia. Patient Blood Management Guidelines. Available from: https://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-guidelines. Accessed 9 Jan 2020.

10. National Blood Authority Australia. Single Unit Transfusion Guide. Available from: https://www.blood.gov.au/single-unit-transfusion. Accessed 9 Jan 2020.

11. Hardy JF. Current status of transfusion triggers for red blood cell concentrates. Transfus Apher Sci 2004;31:55-66. Crossref

12. Zhang Q, Liu L, Sun W, et al. Are closed suction drains necessary for primary total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11290. Crossref

13. Panteli M, Papakostidis C, Dahabreh Z, Giannoudis PV. Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee 2013;20:300-9. Crossref

14. Goodnough LT, Maniatis A, Earnshaw P, et al. Detection, evaluation, and management of preoperative anaemia in the elective orthopaedic surgical patient: NATA guidelines. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:13-22. Crossref

15. Shang J, Wang H, Zheng B, Rui M, Wang Y. Combined intravenous and topical tranexamic acid versus intravenous use alone in primary total knee and hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg 2016;36:324-9. Crossref

16. Benson EE, McMillan DE, Ong B. The effects of active warming on patient temperature and pain after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Nurs 2012;112:26-33. Crossref

17. Rajagopalan S, Mascha E, Na J, Sessler DI. The effects of mild perioperative hypothermia on blood loss and transfusion requirement. Anesthesiology 2008;108:71-7. Crossref

18. Schmied H, Kurz A, Sessler DI, Kozek S, Reiter A. Mild hypothermia increases blood loss and transfusion requirements during total hip arthroplasty. Lancet 1996;347:289-92. Crossref

19. Boutsiadis A, Reynolds RJ, Saffarini M, Panisset JC. Factors that influence blood loss and need for transfusion following total knee arthroplasty. Ann Transl Med 2017;5:418. Crossref

20. Ernest K. Hong Kong Red Cross issues urgent appeal for blood donors as supplies dwindle. South China Morning Post [newspaper on the internet]. 2017 May 4: Health & Environment. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/2092982/hong-kong-red-cross-issues-urgent-appeal-blood. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

21. City urged to donate blood amid severe shortage. The Standard [newspaper on the internet]. 2017 Aug 11: Local. Available from: https://www.thestandard.com.hk/breaking-news/section/3/94995/City-urged-to-donate-blood-amid-severe-shortage. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

22. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Urgent appeal for blood donation [press release]. 2018 Jan 9. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201801/09/P2018010900651.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

23. Coronavirus fears drain Hong Kong's blood banks. Radio Television Hong Kong [newspaper on the internet]. 2020 Feb 12. Available from: https://news.rthk.hk/rthk/en/component/k2/1508174-20200212.htm. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

24. The Annual Report of Hong Kong Red Cross 2018/2019. Available from: https://www.redcross.org.hk/en/publications/annual_reports.html. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

25. World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA63.12: Availability, safety and quality of blood products. Available from: https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19998en/s19998en.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

26. Farmer SL, Towler SC, Leahy MF, Hofmann A. Drivers for change: Western Australia Patient Blood Management Program (WA PBMP), World Health Assembly (WHA) and Advisory Committee on Blood Safety and Availability (ACBSA). Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2013;27:43-58. Crossref

27. Whitaker B, Rajbhandary S, Kleinman S, Harris A, Kamani N. Trends in United States blood collection and transfusion: results from the 2013 AABB Blood Collection, Utilization, and Patient Blood Management Survey. Transfusion 2016;56:2173-83. Crossref

28. Abdullah HR, Ang AL, Froessler B, et al. Getting patient blood management Pillar 1 right in the Asia-Pacific: a call for action. Singapore Med J 2019 May 2. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

29. D E H O, Hadi F, Stevens V. Health economic evaluation comparing iv iron ferric carboxymaltose, iron sucrose and blood transfusion for treatment of patients with iron deficiency anemia (Ida) in Singapore. Value Health 2014;17:A784. Crossref

30. Lee ES, Kim MJ, Park BR, et al. Avoiding unnecessary blood transfusions in women with profound anaemia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2015;55:262-7. Crossref

31. Yoon HM, Kim YW, Nam BH, et al. Intravenous ironsupplementation may be superior to observation in acute isovolemic anemia after gastrectomy for cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:1852-7. Crossref

32. Na HS, Shin SY, Hwang JY, Jeon YT, Kim CS, Do SH. Effects of intravenous iron combined with low-dose recombinant human erythropoietin on transfusion requirements in iron-deficient patients undergoing bilateral total knee replacement arthroplasty. Transfusion 2011;51:118-24. Crossref

33. Lee QJ, Mak WP, Yeung ST, Wong YC, Wai YL. Blood management protocol for total knee arthroplasty to reduce blood wastage and unnecessary transfusion. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2015;23:66-70. Crossref

34. Zmistowski B, Karam JA, Durinka JB, Casper DS, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection increases the risk of one-year mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:2177-84. Crossref

35. Kim JL, Park JH, Han SB, Cho IY, Jang KM. Allogeneic blood transfusion is a significant risk factor for surgical-site infection following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:320-5. Crossref

36. Moskal JT, Harris RN, Capps SG. Transfusion cost savings with tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty from 2009 to 2012. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:365-8. Crossref

37. Lindman IS, Carlsson LV. Extremely low transfusion rates: contemporary primary total hip and knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:51-4. Crossref