Hong Kong Med J 2020 Jun;26(3):192–200 | Epub 21 May 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Attitudes, acceptance, and registration in relation

to organ donation in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study

Jeremy YC Teoh, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)1; Becky SY Lau, BSc, MPH1; Nikki Y Far, FCOphth HK, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)2; Steffi KK Yuen, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)1; CH Yee, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)1; Simon SM Hou, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Timothy SC Teoh, FHKAM (Surgery)3; CF Ng, FRCSEd (Urol), FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Lions Kidney Educational Centre & Research Foundation, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Jeremy YC Teoh (jeremyteoh@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The objective of this study was to

investigate the discrepancy between individuals

with positive attitudes towards organ donation and

the actual number of registered organ donors in

Hong Kong, and to investigate the best modalities

for promoting more organ donor registrations.

Methods: This cross-sectional telephone survey was

conducted in Hong Kong. Telephone numbers were

selected randomly. Upon successful contact with a

household, the eligible household member who had

the most recent birthday was selected to participate

in the telephone interview.

Results: A total of 1000 Hong Kong Chinese residents

were interviewed successfully. The response rate was

53.8%. The majority of the respondents were female

(68.3%) and were aged 51 to 60 years (24%) or ≥61

years (43.6%). Among the respondents, 31.3% were

willing to donate their organs after death; 43.3% were

indecisive, and 25.4% refused. Among those who

were willing to donate organs after death, only 34.2%

had registered with the Centralised Organ Donation

Register (CODR). Among those who were willing to

donate organs after death but had not yet registered

on CODR, 52.2% said they were not determined

enough to take action, 47.8% said they were too

busy, 37.8% said they were too lazy, and 20.4% said

they were always forgetful about registering. In all, 32.8% of the interviewees were not aware of the ways

to register as a prospective organ donor. Among

non-messenger social media platforms, Facebook,

YouTube, and Instagram were the most commonly

used. Most participants believed that Facebook and

YouTube were effective for engaging audiences.

Conclusions: More effort should be made to

facilitate organ donor registration in face-to-face

settings via promotional booths and in online

settings via appropriate social media platforms.

New knowledge added by this study

- A large proportion of respondents had a positive attitude towards organ donation.

- The majority of respondents who were positive towards organ donation lacked the determination to register as organ donors.

- Among respondents who had registered as organ donors, most did so in person via a promotional booth.

- More effort should be made to proactively reach out to passive-positive donors.

- The importance of taking action to register as a prospective organ donor must be emphasised.

- The use of social media platforms may help engage passive-positive donors and provide immediate opportunities for online registration.

Introduction

In 2017, Hong Kong had a low organ donation ratio of

6.0 deceased donors per million population, whereas

the corresponding ratios were 46.9, 32.0, and 23.1

donors per million population in Spain, the United

States, and the United Kingdom, respectively.1 Among all types of solid organs, there is the greatest

shortage of donated kidneys in our locality. In 2018,

there were 2318 patients on the waiting list for

kidney transplantation.2 However, there were only

60 kidney donations from deceased donors and 16

from living donors in the same year.2 This marked mismatch has led to not only a long average waiting

time for kidney transplantation of 51 months,3 but

also the accompanying costs of prolonged dialysis,

increased risk of dialysis-related complications, and

adverse effects on patients’ quality of life.4 5 6

The majority of organ donations are from

deceased donors. However, without knowing the

wishes of deceased potential donors, it is often

difficult to counsel their family members about

organ donation. Therefore, it is important to

engage the general public in prospective organ

donor registration. Hong Kong has a population

of approximately 7.39 million, but only 284 185

individuals had registered as organ donors via the

Centralised Organ Donation Register (CODR)

through June 2018, corresponding to a registration

rate of 3.8%.7 In contrast, 52.6% of the respondents

of the Behavioural Risk Factor Survey conducted in

Hong Kong reported that they were willing to donate

their organs after death.8 These results suggest that

most people who are willing to donate organs after

death have not yet registered as prospective organ

donors. These individuals represent a group of

passive-positive organ donors who would potentially

become prospective organ donors if successfully

engaged.9

We conducted a local survey to investigate the

underlying reasons for the discrepancy between the

number of individuals willing to donate organs and

the number of registered donors. We postulate that

appropriate use of social media may play a role in

motivating people to register as prospective organ donors. Hence, we also investigated the use of

smartphones and social media platforms by Hong

Kong citizens. The results will be useful for planning

our future directions and strategies for promoting

organ donation.

Methods

A cross-sectional telephone survey of the general

population of Hong Kong was conducted via the

service provided by the Jockey Club School of Public

Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University

of Hong Kong. The survey was designed after

consultation with doctors, nurses, living-related

organ donors, organ recipients, and patient support

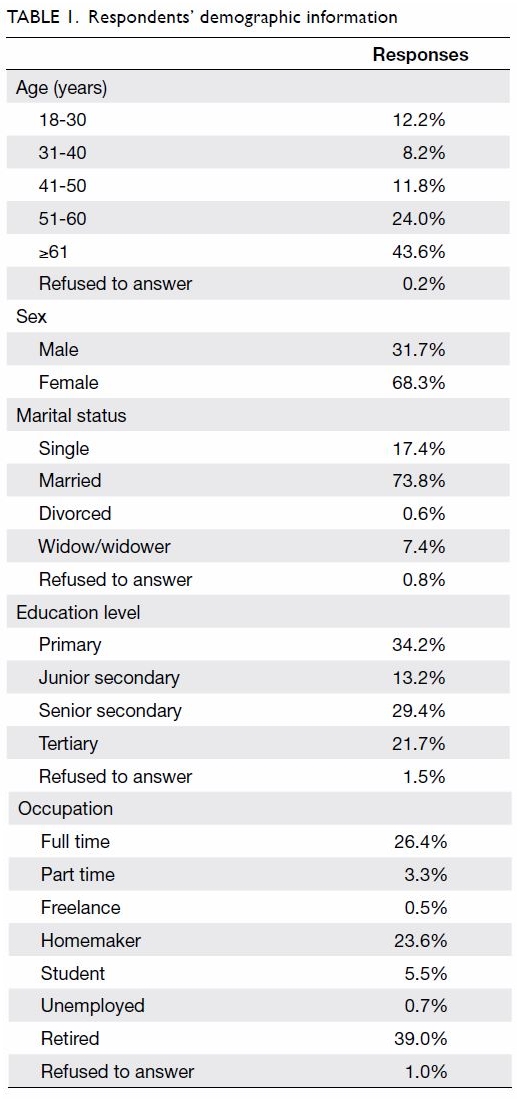

groups. Demographic information including age,

sex, marital status, education level, occupation,

religion, smoking habits, drinking habits, exercise

habits, and current health status was collected.

Questions focusing on the respondents’ views about

organ donation and their actions taken with regard

to organ donor registration were asked. Questions

regarding potential misconceptions about organ

donation were also asked. The respondents’ habits

of using smartphones and social media platforms

were also evaluated. To minimise the sampling error,

telephone numbers were first selected randomly

from an updated telephone directory as seed

numbers. Another set of three numbers was then

generated by randomising the last two digits to

recruit unlisted numbers. Duplicate numbers were

then screened out, and the remaining numbers were

mixed in random order to become the final sample.

Interviews were conducted by experienced

interviewers between 10:00 and 22:00 on weekdays

and other periods, including weekends and public

holidays, should appointments with suitable subjects

be arranged. The inclusion criteria for the study

were Chinese Hong Kong residents aged ≥18 years.

Upon successful contact with a target household,

one qualified member of the household was selected

among the family members using the last-birthday

random selection method (ie, the respondent aged

≥18 years in the household who had his/her birthday

most recently was selected) to participate in the

telephone interview. We aimed for the survey to

have 1000 respondents. All results were analysed

and presented descriptively.

Results

From 15 April 2019 to 8 May 2019, telephone

numbers were sampled for the survey until 1000

valid responses from eligible individuals were

received. Of 16 373 telephone numbers called,

14 514 were invalid for various reasons: 6556 were

facsimile/invalid lines, 555 were non-residential

lines, 1008 cut the line immediately, 6366 did not

pick up the phone after three attempts, and 29 were non-Chinese persons. Among the remaining 1859

eligible individuals, 750 refused to participate in the

survey, seven terminated the survey mid-way, and

we failed to contact the remaining 102 after three

attempted calls each. The overall response rate was

53.8% (1000/1859).

The majority of our respondents were female

(68.3%) and within the age-group of 51 to 60 years

(24%) or ≥61 years (43.6%). In total, 73.6% of the

respondents did not have any religious beliefs. The

vast majority of them were non-smokers (95.2%)

and non-drinkers (93.1%). In all, 65.6% of the

respondents exercised regularly, with 65.7% and

10.3% considering themselves “healthy” and “very

healthy,” respectively (Table 1).

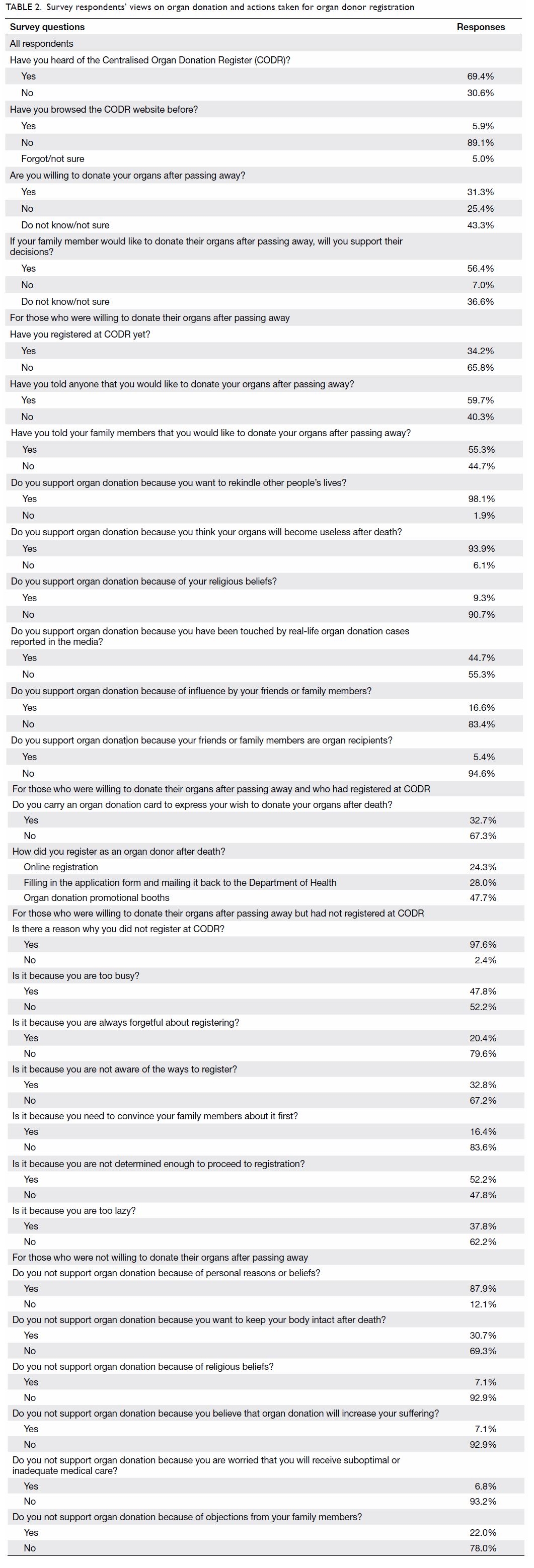

Table 2 shows the survey results on the

respondents’ views about organ donation and their

actions taken with respect to organ donor registration.

Unexpectedly, a relatively large proportion of

interviewees (30.6%) had never heard of CODR, and

89.1% of the respondents had never visited the CODR

website. Only 31.3% of the respondents were willing

to donate their organs after death, and 43.3% were

indecisive, while 25.4% refused. When interviewees

were asked if they would support a family member’s

decision to become a prospective organ donor, 56.4%

said they would be supportive, 7% would object, and

36.6% were uncertain. Looking further at the 313

respondents who were willing to become prospective

organ donors, only 34.2% of them had registered on

CODR, whereas 55.3% had expressed such wishes to

their family members. Of those who had registered,

98.1% did so in the hope of rekindling others’ lives,

93.9% believed that their organs would become

useless after death, and 44.7% were influenced by

successful organ donation stories publicised by the

media.

Of the 107 respondents who had registered

to be prospective organ donors, 47.7% did so via

organ donation promotional booths, 28% filled in

the application forms and mailed them back to the

Department of Health, and 24.3% registered online.

Among the 206 respondents who were willing to

donate organs after death but had not yet registered

on CODR, 52.2% said they were not determined

enough to take action, 47.8% said they were too

busy, 37.8% admitted that they were too lazy to

do so, 20.4% said they were always forgetful about

registering, and 32.8% said they were not aware of

the ways to register as a prospective organ donor.

A total of 687 respondents were indecisive or

refused to become organ donors. In all, 30.7% hoped

to keep their bodies intact after death, 7.1% refused

to register because of religious beliefs, 7.1% were

worried that organ donation might increase their

suffering, and 6.8% worried that by agreeing with

organ donation, they would receive suboptimal or

inadequate medical care. In total, 22% were not keen to donate organs owing to objections from family

(Table 2).

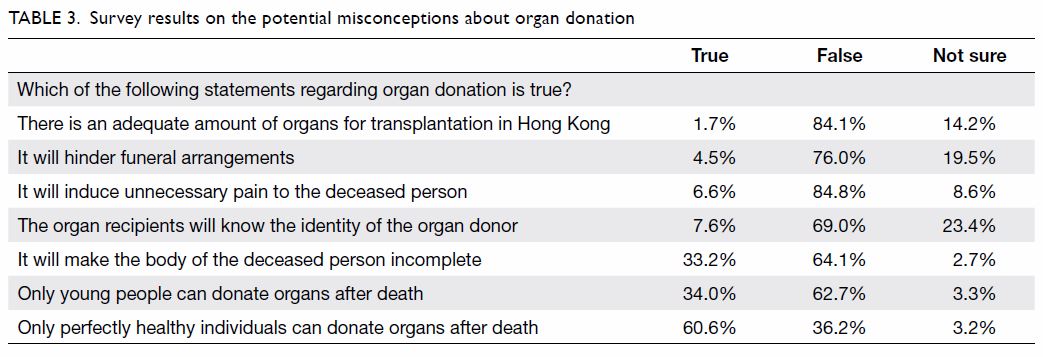

The questionnaire also studied potential

misconceptions about organ donation (Table 3). Of

the respondents, 6.6% believed that the process of

organ harvesting would induce unnecessary pain to

the deceased person, and 4.5% worried that organ

harvesting would hinder funeral arrangements. A

total of 60.6% thought that only perfectly healthy

individuals could donate organs after death, 34%

believed only young people could donate organs after

death, and 7.6% believed that the organ recipients

would always know the identity of the organ donor.

Moreover, 1.7% were under the impression that there

was an adequate supply of organs in Hong Kong.

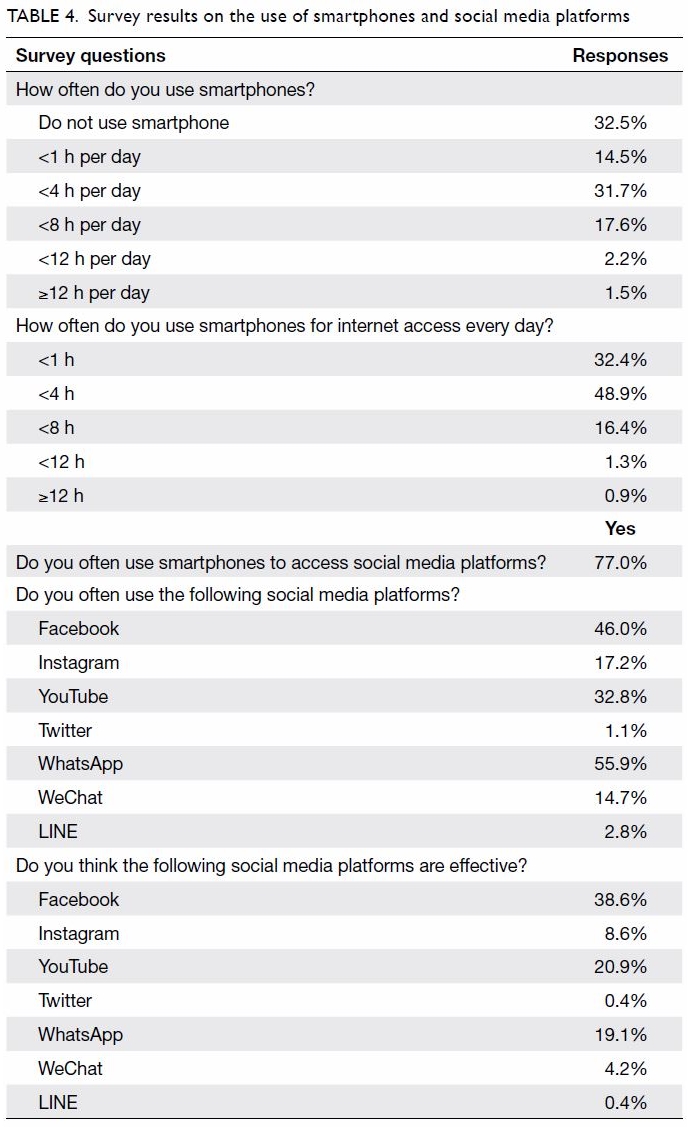

Respondents were interviewed about their

use of smartphones and social media platforms

(Table 4). In all, 77% of the respondents often use

their smartphones to access social media platforms.

Among the various non-messenger types of social

media platforms, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram

were the most commonly used. The majority of the

respondents believed that Facebook and YouTube

were effective at engaging the audience.

Discussion

There has been a great demand for organ

donations in Hong Kong, yet the number of organ

transplantations conducted is very small. The

organ donation rate in Hong Kong is much lower

than that of many European countries, perhaps

because of cultural, religious, governmental, legal,

and regulatory differences, as well as differences in

the level of intensive care unit support and organ

donation criteria.10 11 12 13 Hong Kong currently follows

the opt-in approach to organ donation, as opposed

to the opt-out approach, which is the standard in

countries like Singapore and Spain. Although the

opt-out approach may increase the availability of

suitable organs for donation, there is a reasonable

concern about differing views between members of

the general public and the potential ethical issues

related to that approach. The degree of knowledge,

awareness, and attitude towards organ donation is

also important for an individual to take action to

become a prospective organ donor.14 More efforts

should be made in these areas to improve the organ

donation rate in Hong Kong.

In 2015, a Behavioural Risk Factor Survey with

a total of 4253 respondents was conducted in Hong

Kong.8 Among the respondents, 52.6% reported that

they were willing to donate their organs after death,

11.3% refused to donate their organs after death,

and the rest remained undecided. However, until

June 2018, the registration rate in Hong Kong was only 3.8%.7 This represents a huge area of potential

improvement if we are able to engage these potential

organ donors successfully.

Our survey showed that only 34.2% of the

respondents who were willing to donate their

organs after death actually completed registration

at CODR. A large proportion of respondents said

they were too busy, too lazy, too forgetful, or simply

not determined enough to take action to register at

CODR. Of the respondents, 32.8% were not aware

of the ways to register as a prospective organ donor.

The majority of the respondents had not heard

about CODR, and only 5.9% had browsed the CODR

website. We need better ways to reach out to these

passive-positive donors and to provide convenient

methods for immediate registration after engaging

them successfully. Our survey showed that the

majority of the respondents use smartphones to

access social media platforms every day and that

Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram are the major

social media platforms being used in Hong Kong.

These social media platforms should be used for any

organ donation promotion activities in the future.

Our survey showed that 47.7% of registered

organ donors completed their registration via

organ donation promotional booths. Face-to-face

settings such as promotional booths allow the best

engagement and interaction with the audience, and

this definitely yields better results, especially for

older adults who may not be familiar with the use of

internet or social media platforms. Booths provide

opportunities for educators to clarify people’s

misconceptions, resolve their queries, and provide

live guidance regarding their registration. Our

survey reflected the effectiveness of organ donation

promotion booths established by the Hong Kong

government in the past. It would be worth investing

more resources to set up regular and frequent

promotion booths in more diverse areas owing to

their promising effects.

Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses

have been conducted to identify effective

community-based interventions to increase organ

donor registration.15 16 Among all studies reviewed,

four randomised controlled trials demonstrated the

effectiveness of an intervention based on an increase

in verified organ donor registrations.17 18 19 20 The first

study investigated the role of group discussions about

organ donation in a church setting together with a

32-minute video featuring organ donation, organ

transplantation, and the personnel involved during

the whole process.17 The second study investigated

the effects of a 5-minute video using an iPod Classic

or iPod Touch with noise-cancelling headphones.18

The video was designed to address a number of

concerns related to organ donation. The participants

were then interviewed and given written information

about organ donation. The third study investigated the role of a brief motivational intervention by hair

stylists that encouraged organ donation.19 Hair

stylists received training on communication skills,

motivational interviewing, and discussion of ways to

integrate organ donation into their client interaction.

Each client was given a package containing

organ donor registration cards. The fourth study

investigated the use of the IIFF model (Immediate

opportunity to register, Information, Focused

engagement, and Favourable activation) to increase

the rate of organ donor registration in the setting of

Secretary of State branch offices.20 Participants were

gathered at the Town Hall, where organ donation

was discussed, and there were registration cards at

the end of the session.

The four successful studies have common

features.17 18 19 20 First, all four studies successfully engaged

the public with motivational interactions.17 18 19 20

Intervention participants were 1.23- to 7.02-times

more likely than comparison participants to report

positive registration status.17 18 19 20 Passive-positive

organ donors already have beliefs and attitudes that

favour organ donation; what they need is additional

motivational interactions to convert their belief

into action. Second, three studies adopted a face-to-face approach in their interventions, which

yielded positive results.17 19 20 This is consistent with

our findings, in that we have also seen the positive

effects of face-to-face promotion (ie, booths) in

Hong Kong. Third, two studies used video media

to provide information about organ donation

and organ transplantation.17 18 Mass media alone

are unlikely to produce any substantial effects,

but the combination of media with motivational

interaction can have synergistic effects in engaging

the general public. Media intervention must also

be innovative enough to attract the general public

for better engagement. Fourth, three studies

provided immediate opportunities for organ donor

registration.18 19 20 The opportunity for organ donor

registration must be immediately present following

successful engagement of an individual, and it must

be rapid and convenient enough for the individual to

complete the process. All four studies demonstrated

the effectiveness of their promotion strategies.

Although it might not be suitable to duplicate and

apply those interventions directly in Hong Kong

due to discrepancies in promotion setting and

target audience, by learning from these successful

examples, we can identify the essential components

of a successful organ donation promotion project.

Our study has several limitations. First, we

only randomly selected 1000 Chinese Hong Kong

residents to complete the survey, and this cannot

represent the views of all Hong Kong citizens.

Second, as this was a telephone survey, the majority of

our respondents are aged ≥51 years. The results may

not be a good reflection of the younger generation. Third, although our survey enables us to understand

more about the situation of passive-positive donors

in Hong Kong and the appropriate channels for

engaging these potential organ donors, the exact

ways to achieve audience engagement cannot be

ascertained based only on the results of our survey.

We intend to conduct future studies to investigate

the effectiveness of social media platforms for

interventions such as short videos, online challenge

campaigns, online question-and-answer forums,

online polling, live interviews, and live talks.

Conclusions

There are many passive-positive organ donors in

Hong Kong. Many of those surveyed were not aware

of the ways to register as prospective organ donors.

The majority also lacked the determination to register

as organ donors. Engaging these individuals and

providing immediate opportunities for registration

is necessary. Promotional booths are most effective

at providing this face-to-face, and social media

platforms can provide this on an online setting.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JYC Teoh, NY Far, SKK Yuen, BSY Lau.

Acquisition of data: JYC Teoh, NY Far, SKK Yuen, BSY Lau.

Analysis of data: JYC Teoh, NY Far, SKK Yuen, BSY Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: JYC Teoh, NY Far.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CH Yee, SSM Hou, TSC Teoh, CF Ng.

Acquisition of data: JYC Teoh, NY Far, SKK Yuen, BSY Lau.

Analysis of data: JYC Teoh, NY Far, SKK Yuen, BSY Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: JYC Teoh, NY Far.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CH Yee, SSM Hou, TSC Teoh, CF Ng.

Conflicts of interest

As editors of the journal, JYC Teoh and CF Ng were not

involved in the peer review process. Other authors have

disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This survey was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund, Health Care and Promotion Scheme (Ref: 02180248).

Ethics approval

The study has been approved by Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (Ref SBRE-18-241). Survey

respondents provided verbal consent to participate in the

telephone interview.

References

1. International Registry of Organ Donation and

Transplantation. Donation activity charts. Available from:

http://www.irodat.org/?p=database. Accessed 7 Mar 2020.

2. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Organ donation. Statistics (milestones of Hong Kong

organ transplantation). Available from: https://www.

organdonation.gov.hk/eng/statistics.html. Accessed 1 Oct

2019.

3. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Smart

Patient. Chronic renal failure. Available from: https://

www21.ha.org.hk/smartpatient/SPW/en-US/Disease-

Information/Disease/?guid=368b30e4-cc1c-4185-b673-

7dfb3ea8f74b. Accessed 1 Oct 2019.

4. Karlberg I, Nyberg G. Cost-effectiveness studies of

renal transplantation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care

1995;11:611-22. Crossref

5. Whiting JF, Kiberd B, Kalo Z, Keown P, Roels L, Kjerulf

M. Cost-effectiveness of organ donation: evaluating

investment into donor action and other donor initiatives.

Am J Transplant 2004;4:569-73. Crossref

6. Bakewell AB, Higgins RM, Edmunds ME. Quality of life in

peritoneal dialysis patients: decline over time and association

with clinical outcomes. Kidney Int 2002;61:239-48. Crossref

7. Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch, Centre for Health

Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Registrations recorded in the centralised

organ donation register. Available from: https://www.

organdonation.gov.hk/eng/home.html. Accessed 1 Jun

2018.

8. Surveillance and Epidemiology Branch, Centre for

Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Behavioural risk factor survey (April

2015). Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/

brfs_2015apr_en.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2019.

9. Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Crano WD, Gonzalez AV, Tang

JC, Jones SP. Passive-positive organ donor registration

behavior: a mixed method assessment of the IIFF Model.

Psychol Health Med 2010;15:198-209. Crossref

10. Cheung CY, Pong ML, Au Yeung SF, Chau KF. Factors

affecting the deceased organ donation rate in the Chinese

community: an audit of hospital medical records in Hong

Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:570-5. Crossref

11. Cheung TK, Cheng TC, Wong LY. Willingness for deceased

organ donation under different legislative systems in Hong

Kong: population-based cross-sectional survey. Hong

Kong Med J 2018;24:119-27. Crossref

12. Fan RP, Chan HM. Opt-in or opt-out: that is not the question. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:658-60. Crossref

13. Tafran K. In search of the best organ donation legislative

system for Hong Kong: further research is needed. Hong

Kong Med J 2018;24:318-9. Crossref

14. Chung CK, Ng CW, Li JY, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, and

actions with regard to organ donation among Hong Kong

medical students. Hong Kong Med J 2008;14:278-85.

15. Deedat S, Kenten C, Morgan M. What are effective

approaches to increasing rates of organ donor registration

among ethnic minority populations: a systematic review.

BMJ Open 2013;3:e003453. Crossref

16. Li AT, Wong G, Irving M, et al. Community-based

interventions and individuals’ willingness to be a deceased

organ donor: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Transplantation 2015;99:2634-43. Crossref

17. Andrews AM, Zhang N, Magee JC, Chapman R, Langford

AT, Resnicow K. Increasing donor designation through

black churches: results of a randomized trial. Prog

Transplant 2012;22:161-7. Crossref

18. Thornton JD, Alejandro-Rodriguez M, León JB, et al. Effect

of an iPod video intervention on consent to donate organs:

a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:483-90. Crossref

19. Resnicow K, Andrews AM, Beach DK, et al. Randomized

trial using hair stylists as lay health advisors to increase

donation in African Americans. Ethn Dis 2010;20:276-81.

20. Harrison TR, Morgan SE, King AJ, Williams EA. Saving

lives branch by branch: the effectiveness of driver licensing

bureau campaigns to promote organ donor registry sign-ups

to African Americans in Michigan. J Health Commun

2011;16:805-19. Crossref