Hong Kong Med J 2020 Apr;26(2):120–6 | Epub 14 Apr 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Brain death in children: a retrospective review of

patients at a paediatric intensive care unit

KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1,2; TT Tse3; CC Au, MB, BS, MRCPCH2; WS Lin3; TC Leung3; TC Chow3; CK Li, MB, BS, MD1,2; HM Cheung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; SY Qian, MD4; Alexander KC Leung, MB, BS, MRCPC5

1 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The Hong Kong

Children’s Hospital, Kowloon Bay, Hong Kong

3 Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong

Kong

4 Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical

University, National Center for Children, Beijing, China

5 Department of Paediatrics, The University of Calgary and The Alberta

Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Purpose: Among patients in paediatric intensive

care units (PICUs), death is sometimes inevitable

despite advances in treatment. Some PICU patients

may have irreversible cessation of all brain function,

which is considered as brain death (BD). This study

investigated demographic and clinical differences

between PICU patients with BD and those with

cardiopulmonary death.

Methods: All children who died in the PICU

at a university-affiliated trauma centre between

October 2002 and October 2018 were included in

this retrospective study. Demographics and clinical

characteristics were compared between patients

with BD and patients with cardiopulmonary death.

Results: Of the 2784 patients admitted to the

PICU during the study period, 127 died (4.6%).

Of these 127 deaths, 22 (17.3%) were BD and 105

were cardiopulmonary death. Length of PICU stay

was shorter for patients with cardiopulmonary

death than for patients with BD (2 vs 8.5 days,

P=0.0042). The most common mechanisms of injury

in patients with BD were hypoxic-ischaemic injury

(40.9%), central nervous system infection (18.2%),

and traumatic brain injury (13.6%). The combined

proportion of accident and trauma-related injury

was greater in patients with BD than in patients with

cardiopulmonary death (27.3% vs 3.8%, P<0.001).

Organ donation was approved by the families of four of the 22 patients with BD (18.2%) and was performed

successfully in three of these four patients.

Conclusions: These findings emphasise the

importance of injury prevention in childhood, as

well as the need for education of the public regarding

acceptance of BD and support for organ donation.

New knowledge added by this study

- This 16-year retrospective study compared demographic and clinical differences between patients with brain death and patients with cardiopulmonary death in a Hong Kong paediatric intensive care unit.

- Among 127 deaths, approximately one in five were brain death. Length of paediatric intensive care unit stay was shorter for patients with cardiopulmonary death than for patients with brain death.

- The most common mechanisms of injury in patients with brain death were hypoxic-ischaemic injury, central nervous system infection, and traumatic brain injury. The combined proportion of accident and trauma-related injury was greater in patients with brain death than in patients with cardiopulmonary death.

- Organ donation was approved by the families of four of the 22 patients with brain death (18.2%) and was performed successfully in three of these four patients.

- Family acceptance of the diagnosis of brain death may influence the length of paediatric intensive care unit stay. Without family acceptance of the diagnosis, physicians may be compelled to continue treatment for a patient with brain death.

- Education of the general public and early dialogue between the family and the attending physician are necessary to resolve common misconceptions regarding the biological and legal statuses of patients with brain death.

- Acceptance of the diagnosis of brain death may be associated with acceptance of organ donation and withdrawal of ventilator support, which may improve organ donation rates in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Despite advances in paediatric critical care

medicine, death remains inevitable in some

instances, due to various aetiologies.1 2 In paediatric

critical care medicine settings, patients who

would have otherwise died may be kept ‘alive’ by

advanced cardiovascular and ventilatory support.

Some patients on cardiopulmonary support may

experience irreversible cessation of all brain

function, which is regarded as brain death (BD).3 4 5 6

Because BD or cardiopulmonary death is equivalent

to death, there is no obligation for the physician to

provide further futile treatment.1 2 3 4 7 Nevertheless,

miraculous survivals have been reported in lay media

involving patients who were previously declared

BD or dead, which has created a mis-informed

understanding of BD.8 In this retrospective study,

all patients who underwent BD assessment over a

16-year period were evaluated to determine whether

survival occurred following BD assessment; the

demographics of patients diagnosed with BD were

compared with those of all other patients diagnosed

with cardiopulmonary death at a paediatric intensive

care unit (PICU). The null hypothesis was that there

would be no demographic or clinical differences

between patients diagnosed with BD and those

diagnosed with cardiopulmonary death.

Methods

Study population

All children admitted to the PICU of a university-affiliated

teaching hospital and trauma centre (Prince

of Wales Hospital) between October 2002 and

October 2018 were included in the study. The Prince

of Wales Hospital provides tertiary PICU service for

children, from birth to age 16 years, in the Eastern

New Territories of Hong Kong. The institutional

ethics committee approved this review and waived

the requirement for patient consent.

Data collection

The demographics and clinical characteristics of

deceased children were collected from the principal

author’s database (KLH), in which every PICU

admission was registered; data were also collected

retrospectively from the Clinical Management

System of the hospital. All deaths were reviewed,

including those of patients with clinical evidence

of BD who underwent BD assessment. Brain death

was defined as irreversible loss of all functions of

the brain, including the brainstem. The presence of

coma, absence of brainstem reflexes, and positive

apnoea test were essential findings for diagnosis of

BD. The diagnosis of BD was mainly clinical and

was made in accordance with the hospital’s standard

protocol for paediatric patients.4 9 Patients were

classified either as BD or cardiopulmonary death.

Statistical analysis

The demographics and clinical characteristics of

these two groups of patients were summarised as

median (interquartile range [IQR]) or as number

(percentage), and were compared using the Chi

squared test, Fisher’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney U

test, as appropriate. Patient characteristics included

age, sex, length of PICU stay (time from PICU

admission to withdrawal of ventilator support), and

diagnoses associated with PICU admissions. The

GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software,

La Jolla [CA], US) and SPSS (Windows version

19.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US) were used for

statistical analysis. All comparisons were two-tailed,

and P values <0.05 were considered statistically

significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

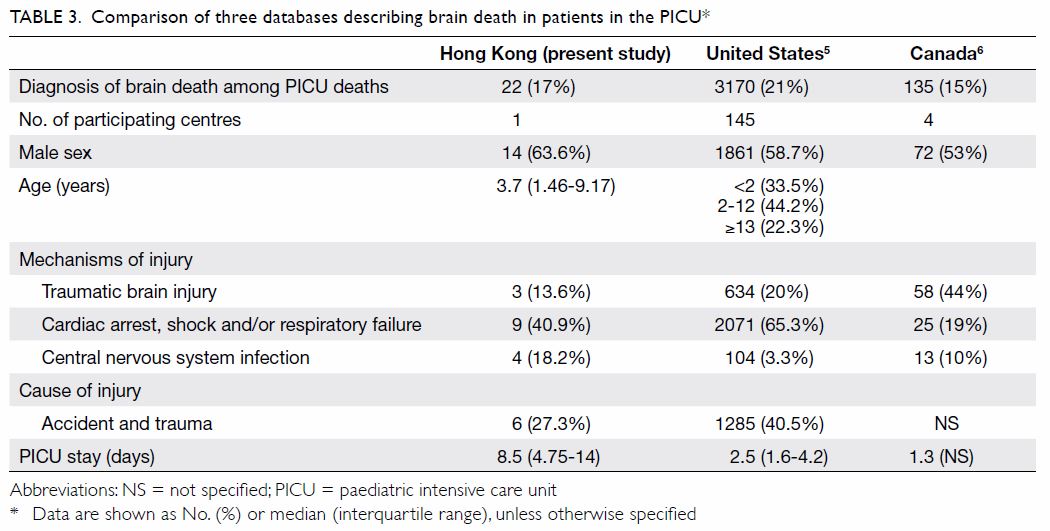

Of the 2784 children admitted to the PICU, 127

(4.6%) died in the PICU (Table 1). All but seven

children were of Chinese ethnicity. There were 73

boys (57.5%) and 54 girls (42.5%); the median age was

3.2 years (IQR: 0.94-7.34 years). Most patients had

not previously been admitted to the PICU (n=103,

81%), and most patients were aged >1 year (74.8%).

Of the 127 patients who died, BD assessments were

performed for 22 (17.3%) patients who had clinical

evidence of BD; all 22 patients were diagnosed

with BD. The remaining 105 (82.7%) patients were

diagnosed with cardiopulmonary death.

Table 1. emographics and clinical characteristics of patients in the PICU with brain death and patients with cardiopulmonary death

Factors associated with brain death and

cardiopulmonary death in patients in

paediatric intensive care unit

Comparison of the two groups showed that

length of PICU stay was significantly longer for

patients with BD (8.5 days; IQR: 4.75-14 days)

than for patients with cardiopulmonary death

(2 days; IQR: 1-10 days; P=0.004). The two groups

shared similar demographics. The most common

diagnoses associated with death in the PICU were

infections (29.1% of patients), oncological diagnoses

(13.0%), and cardiovascular diagnoses (13.8%)

[Table 1]. Comparison of the two groups showed

that trauma (P=0.003) and intracranial events (P=0.041) were more common in patients with BD, whereas respiratory diagnoses (P=0.033) were more

common in patients with cardiopulmonary death.

With respect to the cause of injury, the combined

proportion of accident and trauma-related injury

was greater in patients with BD than in patients with

cardiopulmonary death (27.3% vs 3.8%, P<0.001).

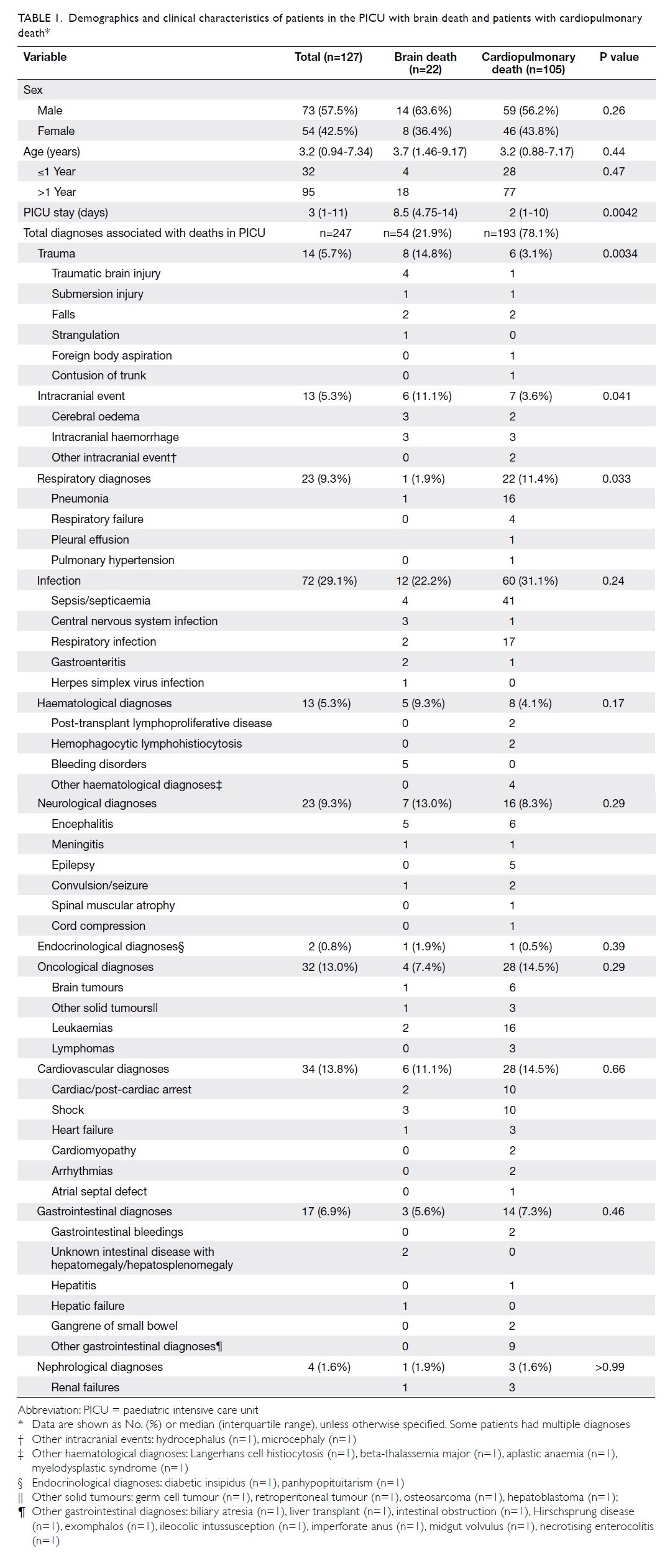

Among patients with BD, the most common

mechanisms of brain injury were hypoxic-ischaemic

injury (eg, cardiac arrest, shock, and/or respiratory

failure), central nervous system infection, and

traumatic brain injury (Table 2). Organ donation was

approved by the families of four of the 22 patients

with BD (18.2%) and was performed successfully in

three of these four patients.

Table 2. Causative mechanisms of injury among patients in the paediatric intensive care unit with brain death

Brain death in patients aged <2 years

Our local guideline for BD determination does

not include patients aged <2 years. Nevertheless,

we found no difference in the proportion of

patients aged <2 years between the BD (n=7) and

cardiopulmonary death groups (n=42) [31.8% and

40%, P=0.47]. There was a non-significant trend

towards greater use of ancillary tests (eg, radionuclide

cerebral perfusion scan or electroencephalography)

for BD determination in patients aged <2 years,

compared with patients aged >2 years (85.7% and 53.3%, P=0.19). The United Kingdom guidelines

recommend that ancillary tests are not required in

infants from gestational age of 37 weeks to 2 months

after birth.10 None of the patients were within this

age range in our study.

Family acceptance of the diagnosis of brain

death

Family acceptance of the diagnosis of BD may

have influenced the length of PICU stay in our

study. Among patients with documented family

acceptance of the diagnosis of BD, the time interval

from BD to withdrawal of ventilator support was

0.5 days (range, 0-1.5 days; n=10). This interval was

prolonged among patients with documented family

resistance of the diagnosis of BD (median, 8 days;

range, 5-16 days; n=5, P=0.005); three of the five

patients’ families eventually accepted withdrawal

of ventilator support, whereas the remaining two

patients remained on ventilator support and lapsed

into cardiac arrest after 16 days and 66 days.

Discussion

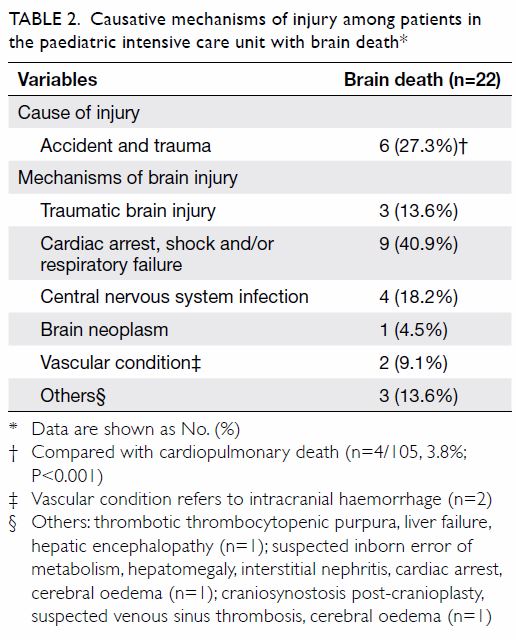

Brain death demographics and survival

Over this 16-year period, BD assessment was only

performed in 22 (17.3%) patients who had clinical

signs of BD; all 22 patients were confirmed to have

BD. Notably, patients with BD had longer length of

PICU stay and a greater combined proportion of

accident and trauma-related injury, while patients

with cardiopulmonary death had a greater frequency

of respiratory diagnoses. In the present study, the

percentage of patients with BD in the PICU was

comparable to the numbers of patients with BD in

two large reports (one from the US and the other

from Canada; Table 3).5 6 Accident and trauma-related injury led to one in four diagnoses of BD in

our study, whereas the proportions of accident and

trauma-related injury, as well as traumatic brain

injury, were higher in the US and Canada.

Brain death and evaluation

Guidelines for BD assessment vary in terms of the

numbers of examinations, numbers and types of

physicians, time intervals between examinations,

and use of ancillary tests.11 12 In general, if BD is

suspected, two physicians (neither of whom would

be involved in organ harvesting from the patient)

should perform two sets of brainstem examinations,

at least 6 hours apart to ensure sufficient observation

time. A single apnoea test should also be performed.

If the results of these tests are positive, the patient

can then be declared legally and clinically BD.1 2 3 4

Before these examinations, conditions that may

confound the clinical diagnosis of BD should be

excluded.1 2 3 4 11 12 Absence of the pupillary reflex to

direct and consensual light, as well as the absence

of corneal, cough, and gag reflexes, support the

clinical diagnosis of BD. The calorie test can aid in

determining the integrity of the oculovestibular

reflex. A positive result consists of the absence of eye

deviation when ice water is irrigated into an external

auditory canal. The apnoea test is performed after

the second examination of brainstem reflexes; only

a single apnoea test is needed. Before the apnoea

test is performed, the physician must confirm that

the patient is not hypothermic, is euvolemic, and

has normal arterial pressure of carbon dioxide

and pressure of oxygen levels. The patient should

then be connected to a pulse oximeter and the

ventilator should be disconnected. Concurrently,

100% O2 is delivered into the trachea at 6 L/min. A

patient with BD may exhibit systolic blood pressure

<90 mm Hg, significant oxygen desaturation, or

cardiac arrhythmia. If respiratory movements are

absent and the arterial pressure of carbon dioxide

is ≥60 mm Hg, the apnoea test result is considered

positive. If the patient is very unstable and an apnoea

test might not be tolerated, or if the results of the

apnoea test are inconclusive, physicians may opt

for other neuro-diagnostic options (eg, four-vessel

cerebral angiography, radionuclide cerebral perfusion

scan, and/or electroencephalography). A lack of

blood perfusion to the brain and lack of electrical

activity would support a diagnosis of BD.

Implications for management of patients with

brain death in the paediatric intensive care

unit

The length of PICU stay was longer for patients

with BD than for patients with cardiopulmonary

death; this differed from the trends observed in the

US and Canada (Table 3).5 6 As noted in the Results,

family acceptance of the diagnosis of BD may have influenced the length of PICU stay in our study.

Unfortunately, not all stakeholders understand or

accept the implications of a diagnosis of BD. In our

experience, the reasons for the family’s resistance

might be two-fold. First, it might be emotionally

difficult to accept the death of a loved one, when the

child is apparently ‘breathing’ and appears physically

‘well’ when ventilatory support is provided. Second,

the family might have confused persistent vegetative

state with BD3 4; notably, patients with persistent

vegetative state have intact brainstem function, while

patients with BD have an irreversible loss of brainstem

function. In such instances of confusion, families may

wish to wait for the patient’s ‘miraculous revival’.1 13 14 15 16 While the acknowledgement of BD as biological

death may be counterintuitive to the public, there

is a need to emphasise and accept that BD is legal

death.17 Thus, public education is necessary to resolve

common misconceptions regarding the biological

and legal statuses of patients with BD.18 Notably,

among university students in Hong Kong, improved

knowledge has been shown to promote acceptance

of the withdrawal of ventilator support following

BD.19 From a physician’s perspective, withdrawal of

ventilator support for patients with BD should not be

regarded as withdrawal of life support; in addition,

continued use of ventilator support that allows a

patient to lapse into cardiac arrest is not a suitable

option. Prolonged and unnecessary treatment in the

PICU prevents other critically ill patients from using

the PICU service; it also constitutes ineffective use

of scarce medical resources. Abuse of PICU beds is

undesirable because medical resources in the public

sector are extremely competitive and limited.20

Further studies regarding physician counselling skills

and family acceptance of the diagnosis of BD may

improve resource utilisation.

Medical professionals should closely monitor

aetiologies that can lead to BD and consider

discussions with affected patients’ families at an early

stage of medical treatment. These early discussions

would allow more time for families to comprehend

the implications of a BD assessment and potential

positive test results. In a previous study, we found

that prolonged length of PICU stay was associated

with a Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation order, which

was placed in nearly half of our PICU deaths; this

finding implied that patients’ families often need

considerable time to accept the end-of-life decision

when futility of medical treatment becomes evident.1

Family acceptance of the diagnosis of BD is critical

for successful management of such situations. If

family acceptance is not achieved, physicians may

become involved in a conflict with the family, which

results in an ethical dilemma regarding the need

to continue treatment for a patient with BD. For

example, one patient in the present study remained

in the PICU for 66 days due to this difficult situation. Communication to identify common values and

establish options based on objective criteria may

resolve potential disputes and allow physicians and

families to reach agreements before, during, and after

BD assessment.21

Implications for organ donation

A practical aspect of BD assessment involves its

implications for the organ donation process. Four

of 22 patients’ families opted for organ donation;

notably, all four families also accepted the diagnosis

of BD. Successful donations of liver or kidneys

were made from three patients. Acceptance of the

diagnosis of BD may be associated with acceptance

of organ donation and withdrawal of ventilator

support.19 Support for organ donation, which was

initiated by the organ transplant coordinator, had

avoided potential instances of conflict. Acceptance of

the diagnosis of BD could be a factor, in combination

with other cultural and religious beliefs, for the lower

organ donation rate than that observed in Western

countries.12

Conclusions

In this study, one in five PICU deaths were BD. Acute

hypoxic-ischaemic injury was the most common

mechanism of brain injury; moreover, accident and

trauma-related injuries were the cause of injury in

one quarter of patients with BD. Diagnosis of BD

was associated with significantly longer PICU stay.

Notably, the organ donation rate was suboptimal.

These findings emphasise the importance of injury

prevention in childhood, as well as the need for

education of the public regarding acceptance of BD

and support for organ donation.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KL Hon.

Acquisition of data: KL Hon, CC Au, TT Tse, WS Lin, TC Leung, TC Chow.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KL Hon, CC Au, TT Tse, WS Lin, TC Leung, TC Chow, AKC Leung.

Drafting of manuscript: KL Hon, CC Au, TT Tse, WS Lin, TC Leung, TC Chow.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KL Hon, CC Au, CK Li, HM Cheung, SY Qian, AKC Leung.

Acquisition of data: KL Hon, CC Au, TT Tse, WS Lin, TC Leung, TC Chow.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KL Hon, CC Au, TT Tse, WS Lin, TC Leung, TC Chow, AKC Leung.

Drafting of manuscript: KL Hon, CC Au, TT Tse, WS Lin, TC Leung, TC Chow.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KL Hon, CC Au, CK Li, HM Cheung, SY Qian, AKC Leung.

All authors have full access to the data, contribute to the

study, approve the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the

peer review process. Other authors have no conflicts of

interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories

East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved

this review (CREC Ref. No. 2016.116).

References

1. Hon KL, Poon TC, Wong W, et al. Prolonged non-survival

in PICU: does a do-not-attempt-resuscitation order matter.

BMC Anesthesiol 2013;13:43. Crossref

2. Hon KL, Luk MP, Fung WM, et al. Mortality, length of stay,

bloodstream and respiratory viral infections in a pediatric

intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2017;38:57-61. Crossref

3. Goila AK, Pawar M. The diagnosis of brain death. Indian J

Crit Care Med 2009;13:7-11. Crossref

4. Sarbey B. Definitions of death: brain death and what

matters in a person. J Law Biosci 2016;3:743-52. Crossref

5. Kirschen MP, Francoeur C, Murphy M, et al. Epidemiology

of brain death in pediatric intensive care units in the United

States. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:469-76. Crossref

6. Joffe AR, Shemie SD, Farrell C, Hutchison J, McCarthy-Tamblyn L. Brain death in Canadian PICUs: demographics,

timing, and irreversibility. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2013;14:1-9. Crossref

7. Citerio G, Murphy PG. Brain death: the European

perspective. Semin Neurol 2015;35:139-44. Crossref

8. Daoust A, Racine E. Depictions of “brain death” in the

media: medical and ethical implications. J Med Ethics

2014;40:253-9. Crossref

9. Verheijde JL, Rady MY, Potts M. Neuroscience and brain

death controversies: the elephant in the room. J Relig

Health 2018;57:1745-63. Crossref

10. Marikar D. The diagnosis of death by neurological criteria

in infants less than 2 months old: RCPCH guideline 2015.

Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2016;101:186. Crossref

11. Greer DM, Varelas PN, Haque S, Wijdicks EF. Variability

of brain death determination guidelines in leading US

neurologic institutions. Neurology 2008;70:284-9. Crossref

12. Chua HC, Kwek TK, Morihara H, Gao D. Brain death: the

Asian perspective. Semin Neurol 2015;35:152-61. Crossref

13. Al-Shammri S, Nelson RF, Madavan R, Subramaniam TA,

Swaminathan TR. Survival of cardiac function after brain

death in patients in Kuwait. Eur Neurol 2003;49:90-3. Crossref

14. Burkle CM, Sharp RR, Wijdicks EF. Why brain death is

considered death and why there should be no confusion.

Neurology 2014;83:1464-9. Crossref

15. Shewmon DA. Chronic “brain death” meta-analysis and

conceptual consequences. Neurology 1998;51:1538-45. Crossref

16. López-Navidad A. Chronic “brain death”: meta-analysis

and conceptual consequences. Neurology 1999;53:1369-70. Crossref

17. Truog RD, Miller FG. Changing the conversation about

brain death. Am J Bioeth 2014;14:9-14. Crossref

18. Shah SK, Kasper K, Miller FG. A narrative review of the

empirical evidence on public attitudes on brain death and

vital organ transplantation: the need for better data to

inform policy. J Med Ethics 2015;41:291-6. Crossref

19. Leung KK, Fung CO, Au CC, Chan DM, Leung GK.

Knowledge and attitudes toward brain stem death among

university undergraduates. Transplant Proc 2009;41:1469-72. Crossref

20. Truog RD. Brain death-too flawed to endure, too ingrained

to abandon. J Law Med Ethics 2007;35:273-81. Crossref

21. Burns JP, Truog RD. Futility: a concept in evolution. Chest

2007;132:1987-93. Crossref