Hong Kong Med J 2020 Apr;26(2):102–10 | Epub 2 Apr 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

External validation of a simple scoring system to

predict pregnancy viability in women presenting

to an early pregnancy assessment clinic

Osanna YK Wan, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FRCOG; Jacqueline PW Chung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Janice WK Kwok, BSc; Terence TH Lao, MD, FRCOG; DS Sahota, BEng, PhD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Osanna YK Wan (osannawan@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: A scoring system combining clinical

history and simple ultrasound parameters was

developed to predict early pregnancy viability

beyond the first trimester. The scoring system

has not yet been externally validated. This study

aimed to externally validate this scoring system to

predict ongoing pregnancy viability beyond the first

trimester.

Methods: This prospective observational cohort

study enrolled women with singleton intrauterine

pregnancies before 12 weeks of gestation. Women

underwent examination and ultrasound scan to

assess gestational sac size, yolk sac size, and fetal

pulsation status. A pregnancy-specific viability

score was derived in accordance with the Bottomley

score. Pregnancy outcomes at 13 to 16 weeks were

documented. Receiver-operating characteristic

curve analysis was used to assess the discriminatory

performance of the scoring system.

Results: In total, 1508 women were enrolled; 1271

were eligible for analysis. After adjustment for

covariates, miscarriage (13%) was significantly

associated with age ≥35 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.99,

95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.19-3.34), higher

bleeding score (OR=2.34, 95% CI: 1.25-4.38), gestational age (OR=1.17, 95% CI: 1.13-1.22), absence

of yolk sac (OR=4.73, 95% CI: 2.11-10.62), absence

of fetal heart pulsation (OR=3.57, 95% CI: 1.87-6.84), mean yolk sac size (OR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.06-1.47), and fetal size (OR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.77-0.88).

The area under the receiver operating characteristic

curve was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89-0.93). Viability score

of ≥1 corresponded to a >90% probability of viable

pregnancy.

Conclusions: The scoring system was easy to use.

A score of ≥1 could be used to counsel women who

have a high likelihood of viable pregnancy beyond

the first trimester.

New knowledge added by this study

- External validation of the Bottomley score was achieved and a cut-off viability score was established. Women with a viability score of ≥1 had a >90% probability that their pregnancy would be carried to beyond the first trimester.

- Miscarriage was significantly associated with age ≥35 years, higher bleeding score, gestational age, absence of yolk sac, absence of fetal heart pulsation, mean yolk sac size, and fetal size.

- A pregnancy with a large subchorionic haematoma (ratio of mean subchorionic haematoma diameter to gestational sac diameter >0.5) was almost two-fold more likely to miscarry, compared with other pregnancies.

- This scoring system allows gynaecologists to use simple clinical history and standard ultrasound measurements to predict pregnancy viability beyond the first trimester

- This score could potentially enhance treatment of women who present with early pregnancy complications, including reassurance of viability among those with high scores and psychological preparation for miscarriage among those with low scores.

Introduction

Miscarriage is the most common early pregnancy

complication, which constitutes a large burden

for patients and the overall healthcare system.

Approximately one in four women experiences early pregnancy loss during her lifetime; such losses

have significant negative psychological and social

impacts on affected women.1 2 3 4 Miscarriage has

been ranked the second most common diagnosis

for admissions in the past 10 years in Hong Kong.5 In-patient hospital admissions for miscarriage were

considerably reduced following establishment of out-patient

early pregnancy assessment clinics (EPACs)

in various hospitals. Women visit EPACs to seek

reassurance that their pregnancy remains viable,

which may be difficult because gestational sac size

and embryonic growth are not uniform6; moreover,

estimates of gestational age are misleading in women

with irregular menstrual periods.7 8 A score that

signifies the likelihood of a viable pregnancy may

be helpful for clinicians working in EPACs.9 10 This

score would enable clinicians to target appropriate

early psychological or clinical support, thereby

minimising psychological morbidity, especially for

patients with finite resources.

Probability models to predict pregnancy

viability have been reported; these combine clinical

history, sonographic assessment of gestational

sac and heart pulsation, and biochemical

measurements.3 9 11 12 13 However, some models cannot

be utilised in initial counselling, because they require

calculators or biochemical measurements which

may not yet be available.9 12 13 In a recent systematic

review regarding prediction of miscarriage in

women with viable intrauterine pregnancy, it was

found that many combinations of markers have been

tested with varying diagnostic accuracy; however, no

meta-analysis could be performed on combination

models.14 Furthermore, the meta-analysis did not

involve assessment of the proportions of women with intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability,

and no scoring system or cut-off value could be

derived for counselling.

The Bottomley score11 is a scoring system

independent of biochemical measurements,

which utilises clinical and ultrasound parameters,

including maternal age, severity of bleeding, and

ultrasound features (eg, mean sizes of gestational

sac and yolk sac, as well as presence of fetal heart

pulsation). It has been validated in comparison

with more complicated probability-based models

in women with intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain

viability; however, the validation study was limited

by small sample size and the exclusion of one third

of the eligible women due to missing variables and

absence of data regarding pregnancy outcomes.12

The scoring system was also limited by the absence of

data regarding body mass index (BMI) and smoking

status, which might affect the likelihood of viable

pregnancy.11 Furthermore, ethnicity influences

miscarriage risk—black women are reportedly more

likely to miscarry than white women,15 whereas rates

among South and East Asian women are reportedly

similar to those of white women after adjustment

for confounders.16 The objective of the present study

was to assess and validate the Bottomley score for

prediction pregnancy viability until 16 weeks of

gestation in a cohort of Chinese pregnant women

who presented to our hospital with threatened

miscarriage or abdominal pain before 12 weeks of

gestation.

Methods

Study design

This non-interventional prospective observational

study was performed at the Prince of Wales Hospital,

Hong Kong, between July 2013 and June 2015.

An out-patient EPAC is available in this hospital

to receive referrals of first trimester pregnant

women with vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain,

or both, and suspected threatened miscarriage,

threatened miscarriage with uncertain viability,

and/or abdominal pain complicating intrauterine

pregnancy; referrals were made by general

practitioners or accident and emergency medical

officers. All gynaecologists at the EPAC had ≥3

years of experience in ultrasound scans, as well as in

diagnosis and treatment of miscarriage.

Patients and clinical assessment

For this study, Chinese women aged ≥18 years with a

singleton intrauterine pregnancy, referred before 12

weeks of gestation based on last menstrual period,

were invited to participate. Participants provided

demographic data for both standard clinical treatment

and determination of the pregnancy viability score.

Women were excluded if they underwent pregnancy termination, had an ectopic or multiple pregnancy,

had pregnancy at an unknown location, or were

diagnosed with miscarriage at the time of initial

presentation. Women with intrauterine pregnancy

of uncertain viability underwent a second ultrasound

examination after 7 to 14 days to determine fetal

viability, in accordance with published guidelines.17 18 19

Detailed information regarding obstetrics

history and history of the current pregnancy were

obtained, including abdominal pain (graded by

pain score) and vaginal bleeding (assessed using a

pictorial blood loss chart with number of pads used;

no bleeding was regarded as a score of 0, while clots

or flooding was regarded as a score of 4). Information

regarding smoking status (smoker or non-smoker),

alcohol intake, and BMI were collected. Smokers

included women who continued to smoke, as well

as those who had discontinued smoking ≤2 weeks

before presentation to our hospital.20 Alcohol

users included women who consumed >2 units per

day, once or twice per week, in the month before

and during their pregnancy.21 Body mass index

was classified in accordance with international

classification as underweight, normal, overweight,

or obese.22

Ultrasound assessment

All women underwent a structured ultrasound

assessment. All transvaginal ultrasound scans were

performed using a GE Voluson 730 ultrasound

machine (GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) to ascertain

the location and viability of the pregnancy. Mean

gestational sac diameter, mean yolk sac diameter,

size of fetal pole, and presence of fetal heart

pulsation were documented. The Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guidelines17 18 and

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

guidelines19 were used for diagnosis of miscarriage,

intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability, viable

pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, or pregnancy of

unknown location. In women with a history of

vaginal bleeding, a hypoechoic or anechoic crescent-shaped

area on ultrasound images was regarded as a

subchorionic haematoma; its three-dimensional size

was classified as small, medium, or large when its

size ratio (relative to gestational sac size) was <0.2,

0.2-0.5, or >0.5, respectively.

Clinical score and patient treatment

Each pregnancy was assigned a Bottomley score based

on clinical history and ultrasound parameters.11 All

clinicians were blinded to the score and all women

in this study were treated in accordance with our

established standard clinical protocols. Pregnancies

were categorised as viable or miscarriage at the repeat

ultrasound scan conducted between 13 and 16 weeks

of gestation, according to the presence or absence of fetal heart pulsation. Women with miscarriage were

treated in accordance with current guidelines.17 19

Watchful waiting, or medical or surgical evacuation

of the uterus, were offered according to each

patient’s clinical condition. For medical evacuation,

misoprostol 800 μg vaginally was used as first-line

treatment, with follow-up assessment to check for

complete evacuation. Patient treatment was not

affected by participation in the study.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Joint

Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories

East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee

(Ref CREC-2013.348). Written informed consent

was obtained from all participants.

Sample size calculations

Bottomley and colleagues11 reported that the areas

under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curves of their score were 0.90 and 0.72 using a

combination of history and ultrasound parameters

and history alone, respectively. To determine

whether the Bottomley score in our local population

exceeded the discriminatory power of the history-alone

model and achieved discriminatory power

similar to that of the combined model, sample size

analysis, using MedCalc Statistical Software version

18.5 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium),

showed that a minimum sample size of 750 was

required for a type 1 error of 1% and power of 90%,

with the assumption that miscarriage occurred in

one of every 10 pregnancies. The planned sample

size was increased to 1500 to allow for the worst-case

scenario of 50% non-participation rate and 50%

loss to follow-up rate.

Statistical analysis

Women were divided into viable or miscarriage groups

according to pregnancy outcome. Comparisons of

socio-demographic and pregnancy characteristics

between the two outcome groups were performed

using the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test,

where appropriate, for categorical variables; the

Mann-Whitney U test with post hoc Bonferroni

correction was used for comparisons of continuous

variables. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) of significant predictors

of miscarriage were determined by multivariate

logistic regression analysis. Receiver operating

characteristic curves were constructed to determine

the discriminatory performance of the Bottomley

score, as well as to determine the Bottomley score

which predicted 90% viable pregnancies at the

repeat ultrasound scan. Probit regression, with

Bottomley score as the only independent predictor,

was performed to estimate the probability of an ongoing viable pregnancy beyond the first trimester.

Bottomley scores were truncated to a minimum value

of -12 and a maximum value of 18, prior to Probit

regression and ROC analyses. Patients lost to follow-up

were excluded from the study. All analyses were

performed using SPSS Statistics, version 20.0 (IBM

Corp., Armonk [NY], United States) and MedCalc.

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and ultrasound

measurements

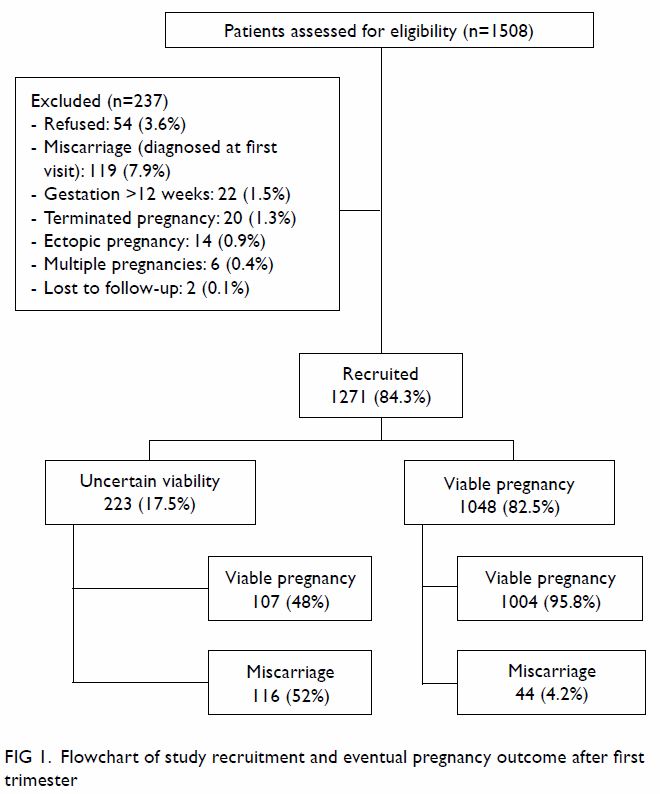

Of the 1508 women invited to participate, 54 (3.6%)

declined and two (0.1%) were lost to follow-up at 13

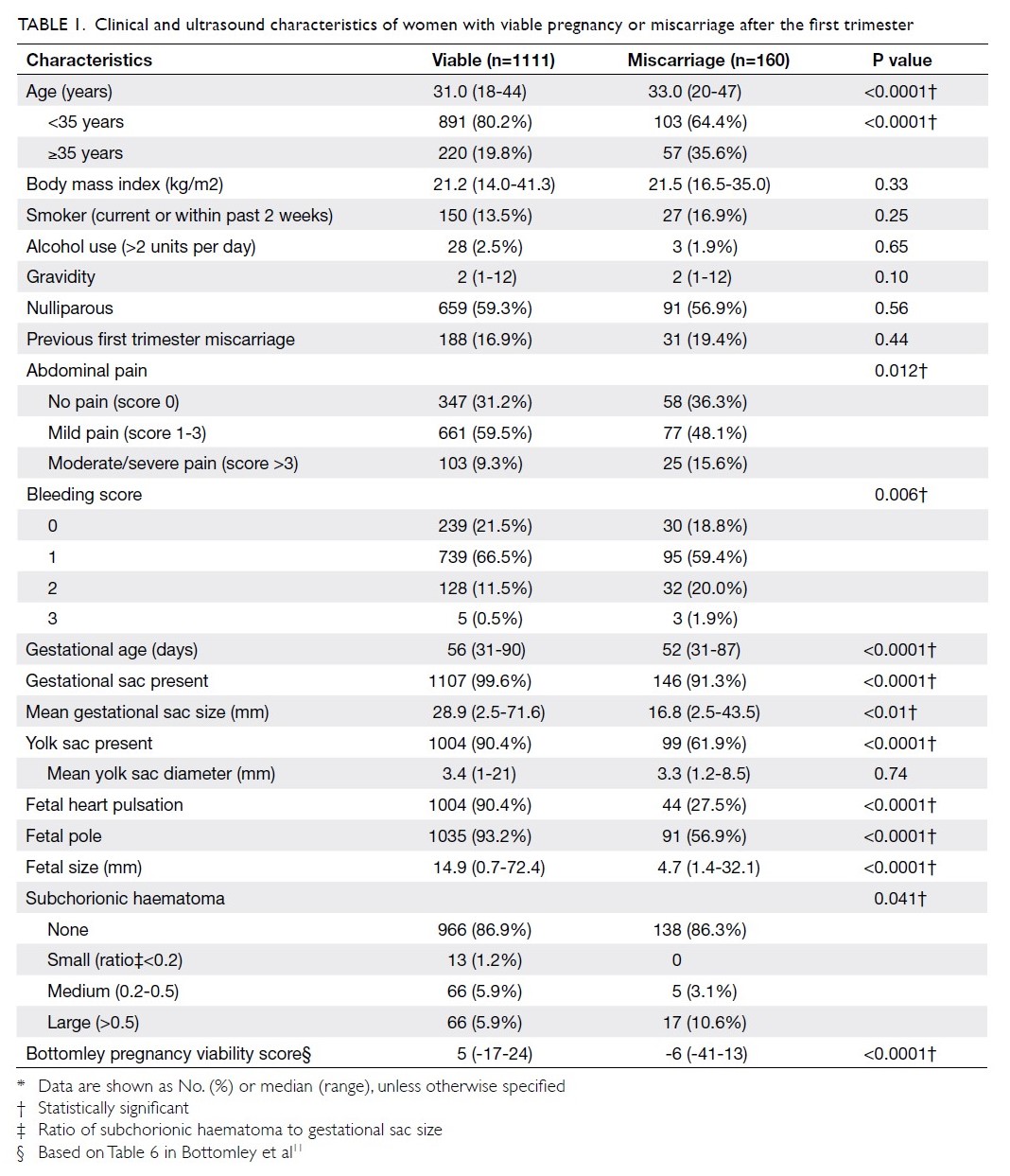

to 16 weeks of gestation (Fig 1). Table 1 summarises

the socio-demographic characteristics, clinical signs

and symptoms, and ultrasound measurements in the

two outcome groups. The Bottomley score ranged

from -41 to 24; 36 women (2.8%) had a score of

≤-12, and 64 (5.0%) had a score ≥18, while the score

ranged from -12 to +1 in women with a pregnancy of

uncertain viability at first assessment.

Table 1. Clinical and ultrasound characteristics of women with viable pregnancy or miscarriage after the first trimester

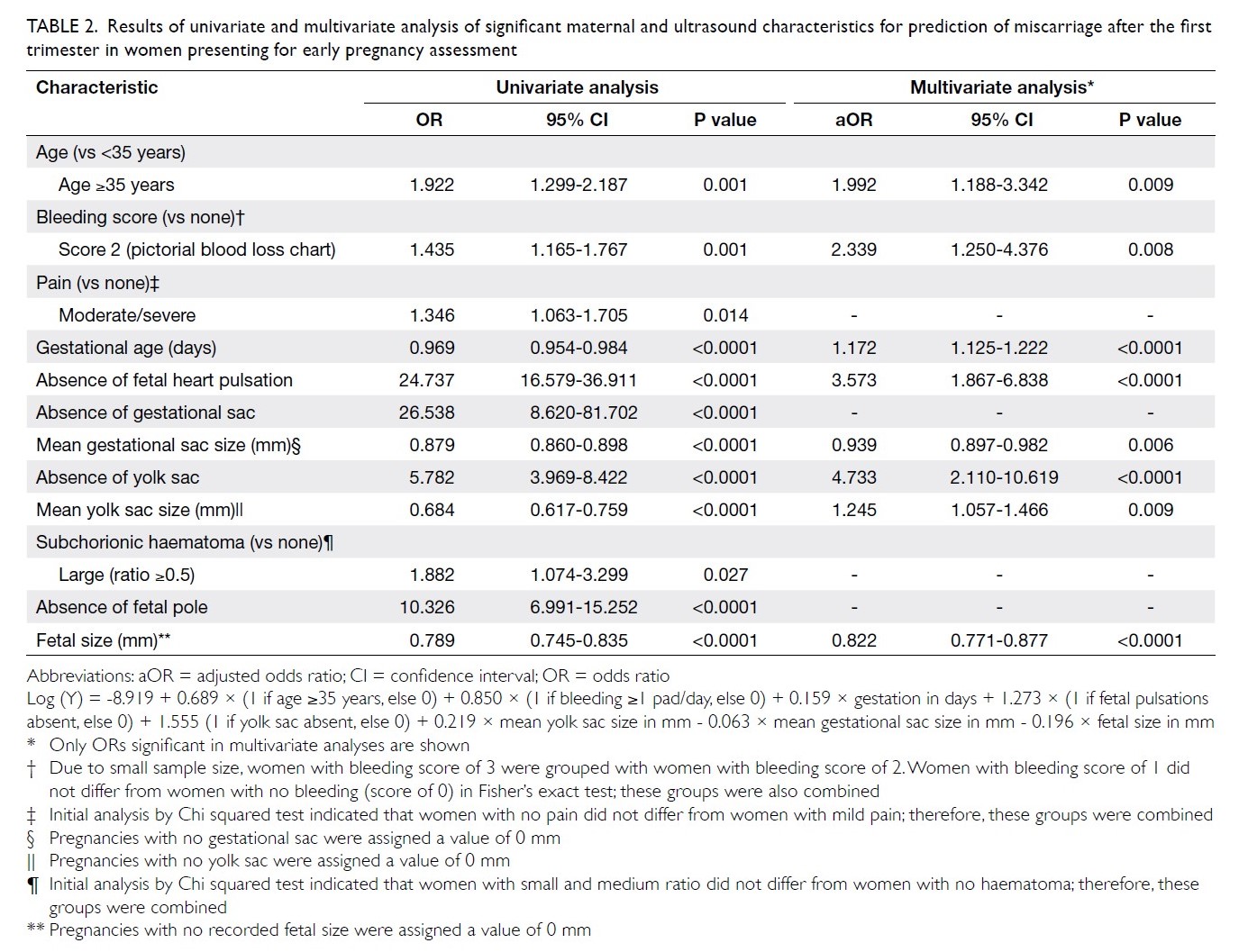

Risk of miscarriage

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs for risk of miscarriage

after adjusting for covariates are summarised in

Table 2. Subchorionic haematoma was noted in 167

pregnancies (13.1%), including 138 (82.6%) with

bleeding. Haematoma size relative to gestational sac

size was significantly associated with miscarriage

(χ2=70.5, P<0.05) [Tables 1 and 2]. A pregnancy

with a large haematoma was nearly two-fold more

likely to miscarry, compared with other pregnancies

(17/160 [10.6%] vs 66/1111 [5.9%]).

Table 2. Results of univariate and multivariate analysis of significant maternal and ultrasound characteristics for prediction of miscarriage after the first trimester in women presenting for early pregnancy assessment

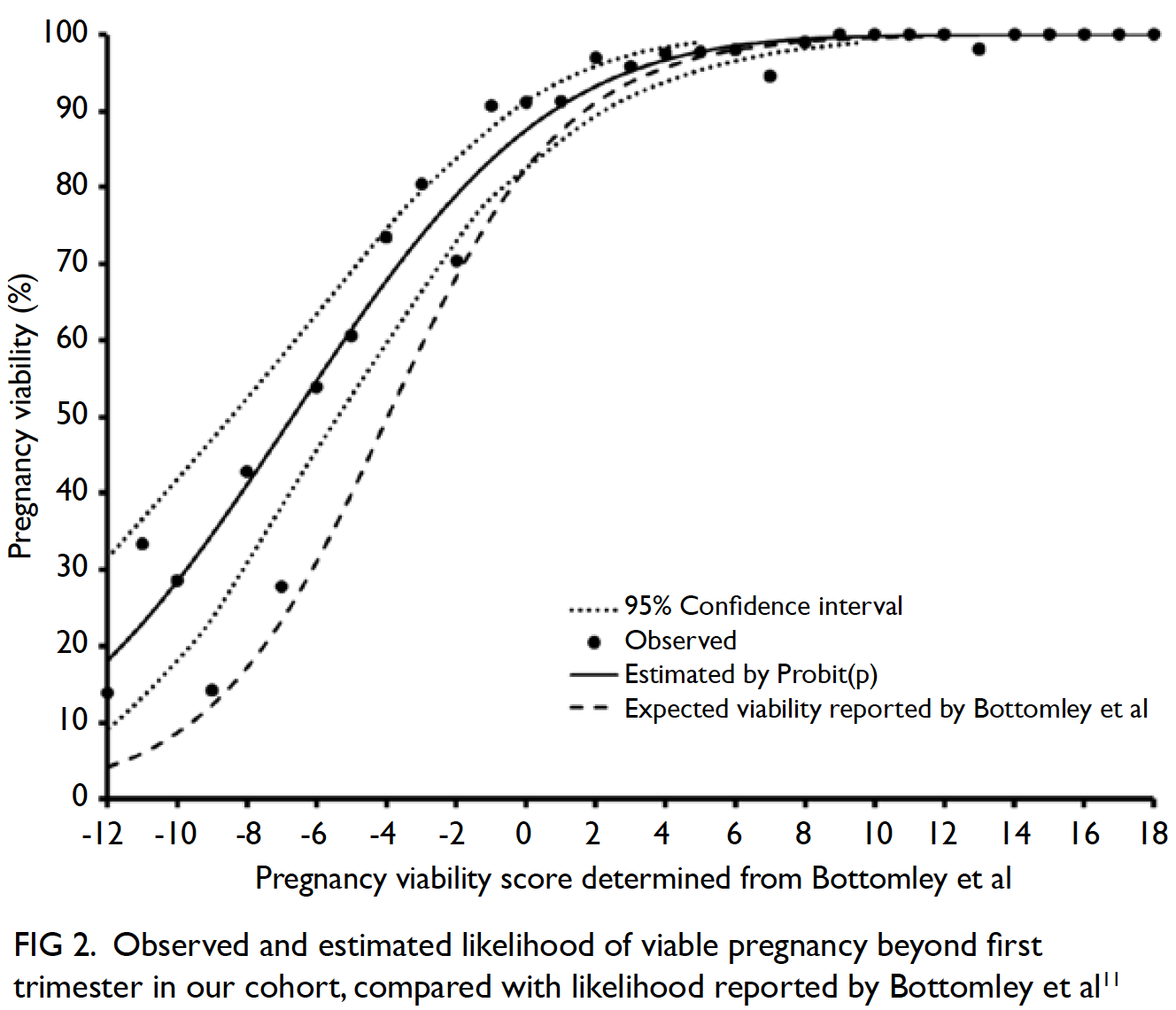

Predictive performance of Bottomley score

The area under the ROC curve of the discriminatory

performance of the Bottomley score in all women

was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89-0.93, P<0.001). A score of ≥1

had a sensitivity of 91% (95% CI: 85.8-95.1%) and a

false positive rate of 26.7% (95% CI: 24.1-29.4%).

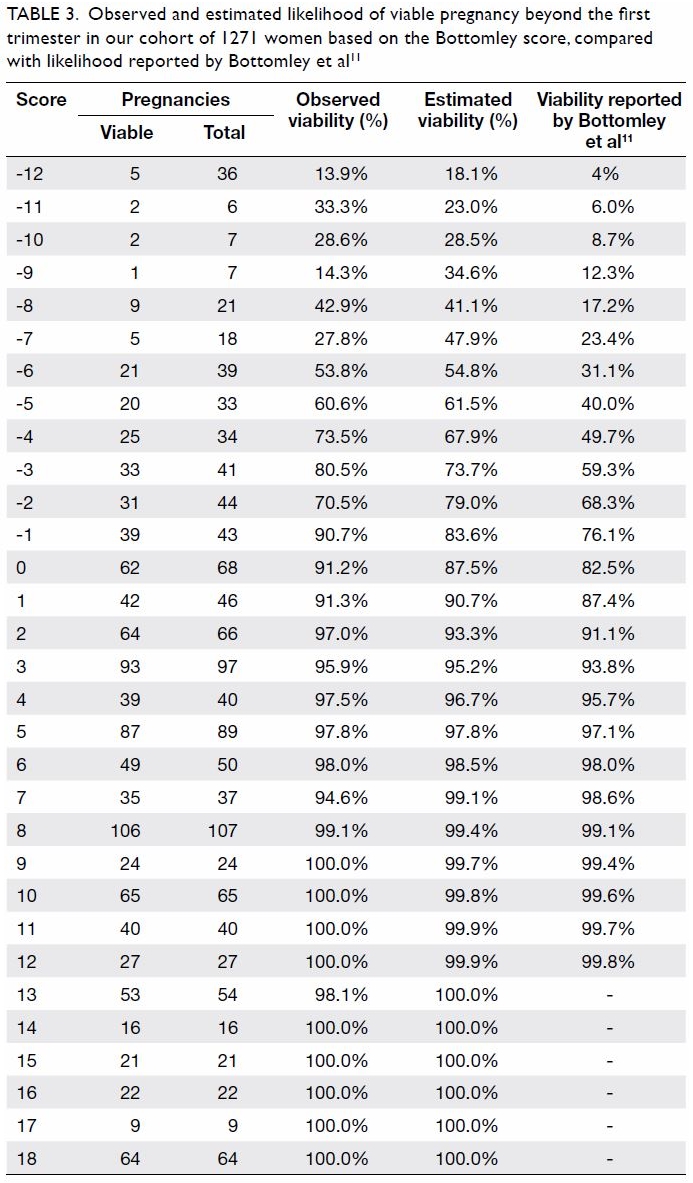

Figure 2 and Table 3 show the observed and

estimated viability of a pregnancy after the first

trimester, compared with the viability estimates

by Bottomley et al11 at each viability score. The

estimated probability of viability for a particular

pregnancy, based on the Bottomley score, was

determined: Probit(p) = 1.15109 + 0.17188 × score.

Table 3. Observed and estimated likelihood of viable pregnancy beyond the first trimester in our cohort of 1271 women based on the Bottomley score, compared with likelihood reported by Bottomley et al11

The estimated probability of viability reported

by Bottomley and colleagues11 was within the 95%

CI of the estimated probability determined by our

Probit(p) function if the viability score was ≥0. The

area under the ROC curve of the Bottomley score

in women with a pregnancy of uncertain viability at

initial presentation was only 0.74 (95% CI: 0.67-0.80).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report

of independent external validation of the scoring

system proposed by Bottomley et al.11 to predict early

second trimester pregnancy viability in women with

intrauterine pregnancy before 12 weeks of gestation.

Moreover, it is the first study in a homogenous

Chinese population. Our findings indicated that the

Bottomley score could be used to predict the likely

outcome of pregnancy, thus potentially alleviating

maternal anxiety; this is particularly useful for

women with symptoms of threatened miscarriage.

The scoring system is simple to use and does

not require a calculator (in contrast to previous

models)8 11; moreover, it relies solely on information

that can be readily obtained by any gynaecologist,

without the need for blood tests.3 12 Women with

a Bottomley score of ≥1 had a >90% probability of

pregnancy viability beyond the first trimester. These

women could be reassured, and further ultrasounds

could be avoided. A low Bottomley score was

associated with increased likelihood of miscarriage,

such that half of the women with a score of -7 or -6

were expected to miscarry; this proportion reached 80% if the score was ≤-12. Proper counselling could

be offered to prepare these women psychologically,

thereby reducing the impact of pregnancy loss.

This scoring system incorporates several

different variables that interact with each other. For

example, a larger but empty gestational sac increases

the likelihood of miscarriage, thus resulting in a

lower (ie, more negative) score; however, this lower

score would be counterbalanced by the presence

of fetal heart pulsation and an appropriately sized yolk sac. In addition, although a negative score was

unexpectedly determined for pregnancies with the

presence of fetal heart pulsation, this negative score

could be counterbalanced by a positive score for a

larger gestational sac size.

Notable strengths in this study include its

use of a priori determination of sample size to

assess discriminatory performance. Moreover, the

participation rate was high and few pregnancies were

lost to follow-up. The resulting large sample size enabled assessment of discriminatory performance

of the scoring system; it also allowed identification

of predictors of miscarriage in our cohort of Chinese

women and provided estimated sensitivities (±5%)

at specific viability scores. Whereas only 10% of

included patients were of Asian ethnicity in the

study by Bottomley et al,11 our study was performed

in a homogenous Chinese population; therefore, our

findings suggest that the score is likely to be valid for

various Asian populations, although further studies

are necessary to validate its use in different Asian

subgroups.

This scoring system was designed for use in

all pregnant women with an intrauterine pregnancy

before 12 weeks of gestation. Our analysis of the

performance of this scoring system in pregnancies

with uncertain viability alone also showed reasonable

performance: pregnancy failure could be predicted in

women with pregnancies of uncertain viability, with

an area under the ROC curve of >0.5. However, this

finding should be interpreted with caution, because

there were only 223 women in this subgroup; our sample size was only sufficient to detect an area

under the ROC curve of 0.65, assuming that the

ratio of miscarriage to viability was 1:1. Of note,

while the scoring system was reliable for estimation

of pregnancy viability until 16 weeks of gestation, the

implication of each score differed, compared with

the previous study.11

Lastly, the miscarriage rate in this study was

13%, approximately 50% lower than the 20% to

30% rates reported by Kong et al1 and Bottomley

et al.11 However, the observed rate of miscarriage

among women with intrauterine pregnancy of

uncertain viability at presentation was consistent

with the rates observed in other studies.11 12 The

relatively low overall miscarriage rate could have

been due to differences in local referral practices,

because some women attending our EPAC were

asymptomatic, whereas women with heavy vaginal

bleeding or severe abdominal pain might have been

admitted directly for treatment; we were unable to

ascertain how many women with early pregnancy

loss were directly admitted without referral to the

EPAC. We excluded women with ectopic pregnancy

or pregnancy of unknown location because these

women had empty uteri. By focusing on women with

intrauterine pregnancy irrespective of viability, we

presumed that our study would be more likely to

generate useful clinical information for counselling

if the model were validated. Notably, excluded

women comprised only 0.9% of all women invited to

participate in the study.

Other potential explanations for the low

miscarriage rate could be differences in lifestyle

factors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption,

as well as incidence of obesity; in contrast to the

findings in published literature,23 24 these factors

were not associated with pregnancy outcome.

Smoking during pregnancy is rare in Chinese

women.25 Obesity is also uncommon; in the present

study only 35 women (2.7%) had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2,

while the median weight of 53.3 kg and median BMI

of approximately 21-21.5 kg/m2 in this study were

similar to the characteristics of women attending

a first trimester Down syndrome screening clinic

and of pregnant women enrolled in another

prospective study (regarding the pelvic floor) in our

centre.26 27 Lastly, the median duration of gestation

at presentation to EPAC was 55 days in our study,

whereas it was 50 days in the study by Bottomley

et al.11 This could have contributed to our lower

miscarriage rate, which decreases with gestational

age.

Consistent with the findings of other studies,

our multivariate analysis indicated that the following

factors were associated with increased likelihood of

miscarriage: increasing age, absence of fetal heart

pulsation, heavier bleeding, and a large subchorionic

haematoma. In addition to miscarriage, subchorionic haematoma increases the risk of placental abruption

and preterm premature rupture of membranes.28

We previously proposed classification of the three

sizes of the subchorionic haematoma, in relation

to gestational sac size.29 We suggested assessment

of the size of subchorionic haematoma relative to

the gestational sac, rather than the mere presence

or absolute size of subchorionic haematoma, in

accordance with the approach used by clinicians in

the United States.30 This parameter was expected

to enhance prediction of miscarriage, but this hypothesis was not supported by multivariate

analysis results; further studies are needed to

more thoroughly investigate the usefulness of this

parameter.

Conclusion

The results of our external validation study

suggested that the scoring system would reliably

predict probable pregnancy viability, despite slight

differences in score implication. Application of this

score could potentially enhance the treatment of

women who initially present with early pregnancy

complications. The cut-off value obtained in this

study may be useful when counselling pregnant

women. Further studies will be performed in our

study centre to determine whether this externally

validated scoring system could be utilised to

reduce psychological morbidity by reassuring the

women likely to maintain a viable pregnancy, while

psychologically preparing other women for expected

miscarriage.

Author contributions

Concept or design: OYK Wan, SSC Chan, JPW Chung.

Acquisition of data: OYK Wan, JWK Kwok

Analysis or interpretation of data: OYK Wan, JWK Kwok, DS Sahota.

Drafting of the manuscript: OYK Wan, DS Sahota, TTH Lao.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: OYK Wan, SSC Chan, JPW Chung, TTH Lao, DS Sahota.

Acquisition of data: OYK Wan, JWK Kwok

Analysis or interpretation of data: OYK Wan, JWK Kwok, DS Sahota.

Drafting of the manuscript: OYK Wan, DS Sahota, TTH Lao.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: OYK Wan, SSC Chan, JPW Chung, TTH Lao, DS Sahota.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not involved in the peer review process. The remaining authors have no

conflicts of interest to disclose.

Declaration

The results from this research have been presented, in part, at

the following conferences:

1. Wan O, Chan SS, Kong G. A prospective observational study to validate the reliability of the early pregnancy viability scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(Suppl 1):42. (Oral presentation)

2. Kwok J, Wan O, Chan SS. Subchorionic hematoma: its size and association with early pregnancy outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(Suppl 1):172. (Poster presentation)

3. Wan OY, Chan SS, Kong GW. A prospective observational study to validate the reliability of the early pregnancy viability scoring system. FOCUS in O&G 2015 Congress; 2015. May 30-31; Shatin, Hong Kong. The Chinese University of Hong Kong; 2015. (Oral presentation)

4. Wan OY, Chan SS, Kong GW. External validation of an early pregnancy viability prediction model via a prospective observational study. RCOG World Congress; 2016. Jun 20-22; Birmingham: United Kingdom; 2016. (Poster presentation)

1. Wan O, Chan SS, Kong G. A prospective observational study to validate the reliability of the early pregnancy viability scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(Suppl 1):42. (Oral presentation)

2. Kwok J, Wan O, Chan SS. Subchorionic hematoma: its size and association with early pregnancy outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(Suppl 1):172. (Poster presentation)

3. Wan OY, Chan SS, Kong GW. A prospective observational study to validate the reliability of the early pregnancy viability scoring system. FOCUS in O&G 2015 Congress; 2015. May 30-31; Shatin, Hong Kong. The Chinese University of Hong Kong; 2015. (Oral presentation)

4. Wan OY, Chan SS, Kong GW. External validation of an early pregnancy viability prediction model via a prospective observational study. RCOG World Congress; 2016. Jun 20-22; Birmingham: United Kingdom; 2016. (Poster presentation)

Funding/support

This research was supported by a research grant from the

Health and Medical Research Fund of Food and Health

Bureau, Hong Kong SAR (HMRF Reference: 12131091). The

study sponsor was not involved in the collection, analysis, or

interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref CREC-2013.348). Written informed

consent was obtained from all the participants.

References

1. Kong GW, Lok IH, Yiu AK, Hui AS, Lai BP, Chung TK.

Clinical and psychological impact after surgical, medical

or expectant management of first-trimester miscarriage—a

randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol

2013;53:170-7. Crossref

2. Lok IH, Yip AS, Lee DT, Sahota D, Chung TK. A 1-year

longitudinal study of psychological morbidity after

miscarriage. Fertil Steril 2010;93:1966-75. Crossref

3. Elson J, Salim R, Tailor A, Banerjee S, Zosmer N, Jurkovic

D. Prediction of early pregnancy viability in the absence of

an ultrasonically detectable embryo. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 2003;21:57-61. Crossref

4. Volgsten H, Jansson C, Darj E, Stavreus-Evers A. Women’s

experiences of miscarriage related to diagnosis, duration,

and type of treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

2018;97:1491-8. Crossref

5. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Territory-wide Obstetrics and Gynaecology Audit

Report 2009. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists; 2014.

6. Abdallah Y, Daemen A, Guha S, et al. Gestational sac

and embryonic growth are not useful as criteria to define

miscarriage: a multicenter observational study. Ultrasound

Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:503-9. Crossref

7. Bottomley C, Bourne T. Dating and growth in the

first trimester. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2009;23:439-52. Crossref

8. Doubilet PM. Should a first trimester dating scan be

routine for all pregnancies? Semin Perinatol 2013;37:307-9. Crossref

9. Oates J, Casikar I, Campain A, et al. A prediction model

for viability at the end of the first trimester after a single

early pregnancy evaluation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol

2013;53:51-7. Crossref

10. Stamatopoulos N, Lu C, Casikar I, et al. Prediction of

subsequent miscarriage risk in women who present with a

viable pregnancy at the first early pregnancy scan. Aust N

Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2015;55:464-72. Crossref

11. Bottomley C, Van Belle V, Kirk E, Van Huffel S, Timmerman

D, Bourne T. Accurate prediction of pregnancy viability by

means of a simple scoring system. Hum Reprod 2013;28:68-76. Crossref

12. Guha S, Van Belle V, Bottomley C, et al. External validation

of models and simple scoring systems to predict miscarriage

in intrauterine pregnancies of uncertain viability. Hum

Reprod 2013;28:2905-11. Crossref

13. Ku CW, Allen JC Jr, Malhotra R, et al. How can we better

predict the risk of spontaneous miscarriage among women

experiencing threatened miscarriage? Gynecol Endocrinol

2015;31:647-51. Crossref

14. Pillai RN, Konje JC, Richardson M, Tincello DG, Potdar

N. Prediction of miscarriage in women with viable

intrauterine pregnancy—a systematic review and

diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol

Reprod Biol 2018;220:122-31. Crossref

15. Mukherjee S, Velez Edwards DR, Baird DD, Savitz DA,

Hartmann KE. Risk of miscarriage among black women

and white women in a U.S. prospective cohort study. Am J

Epidemiol 2013;177:1271-8. Crossref

16. Khalil A, Rezende J, Akolekar R, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides

KH. Maternal racial origin and adverse pregnancy

outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynaecol

2013;41:278-85. Crossref

17. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

The Management of Early Pregnancy Loss. Green-top

Guideline No 25, 2006. Available from: http://www.jsog.

org/GuideLines/The_management_of_early_pregnancy_

loss.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

18. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Addendum to GTG No 25 (Oct 2006). Available from:

https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/news/

addendum-to-gtg-no-25.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

19. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial

management. Clinical guideline [CG154]. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG154. Accessed 7

Aug 2019.

20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Smoking:

stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth. Public Health

guideline [PH26]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.

uk/guidance/ph26. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies. Clinical

guideline [CG62]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.

uk/Guidance/CG62. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

22. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index

for Asian populations and its implications for policy and

intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63. Crossref

23. Pan Y, Zhang S, Wang Q, et al. Investigating the association

between prepregnancy body mass index and adverse

pregnancy outcomes: a large cohort study of 536 098

Chinese pregnant women in rural China. BMJ Open

2016;6:e011227. Crossref

24. Pineles BL, Park E, Samet JM. Systematic review and metaanalysis

of miscarriage and maternal exposure to tobacco

smoke during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:807-

23. Crossref

25. Kong GW, Tam WH, Sahota DS, Nelson EA. Smoking

pattern during pregnancy in Hong Kong Chinese. Aust N

Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:280-5. Crossref

26. Sahota DS, Leung WC, Chan WP, To WW, Lau ET,

Leung TY. Prospective assessment of the Hong Kong

Hospital Authority universal Down syndrome screening

programme. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:101-8.

27. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu AK, et al. Prevalence of levator

ani muscle injury in Chinese women after first delivery.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012;39:704-9. Crossref

28. Tuuli MG, Norman SM, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill

AG. Perinatal outcomes in women with subchorionic

hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet

Gynecol 2011;117:1205-12. Crossref

29. Kwok J, Wan O, Chan SS. P16.02: Subchorionic hematoma:

its size and association with early pregnancy outcome.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46(Suppl 1):172. Crossref

30. Heller HT, Asch EA, Durfee SM, et al. Subchorionic

hematoma: correlation of grading techniques with

first-trimester pregnancy outcome. J Ultrasound Med

2018;37:1725-32. Crossref