Expanded carrier screening using next-generation sequencing of 123 Hong Kong Chinese families: a pilot study

Hong Kong Med J 2021 Jun;27(3):177–83 | Epub 19 Feb 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Expanded carrier screening using next-generation

sequencing of 123 Hong Kong Chinese families:

a pilot study

Olivia YM Chan, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1,2 #; TY Leung, FRCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1,3 #; Y Cao, PhD1,3,4; MM Shi, MPhil1; Angel HW Kwan, MRCOG1; Jacqueline PW Chung, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; KW Choy, PhD1,3; SC Chong, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)3,4

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Adept Medical Centre, Hong Kong

3 The Chinese University of Hong Kong–Baylor College of Medicine Joint Center of Medical Genetics, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

# These authors equally contributed to this work

Corresponding author: Dr SC Chong (chongsc@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: To determine the carrier frequency

and common mutations of Mendelian variants in

Chinese couples using next-generation sequencing

(NGS).

Methods: Preconception expanded carrier testing

using NGS was offered to women who attended

the subfertility clinic. The test was then offered to

the partners of women who had positive screening

results. Carrier frequency was calculated, and the

results of the NGS panel were compared with those of

a target panel.

Results: In total, 123 women and

20 of their partners were screened. Overall, 84 (58.7%)

individuals were identified to be carriers of at least

one disease, and 68 (47.6%) were carriers after

excluding thalassaemias. The most common diseases

found were GJB2-related DFNB1 nonsyndromic

hearing loss and deafness (1 in 4), alpha-thalassaemia

(1 in 7), beta-thalassaemia (1 in 14), 21-hydroxylase

deficient congenital adrenal hyperplasia (1 in 13),

Pendred’s syndrome (1 in 36), Krabbe’s disease (1 in

48), and spinal muscular atrophy (1 in 48). Of the

43 identified variants, 29 (67.4%) were not included

in the American College of Medical Genetics and

Genomics or American College of Obstetrics and

Gynecology guidelines. Excluding three couples

with alpha-thalassaemia, six at-risk couples were

identified.

Conclusion: The carrier frequency of the investigated

members of the Chinese population was 58.7%

overall and 47.6% after excluding thalassaemias.

This frequency is higher than previously reported.

Expanded carrier screening using NGS should be

provided to Chinese people to improve the detection

rate of carrier status and allow optimal pregnancy

planning.

New knowledge added by this study

- The carrier frequency of Mendelian variants in the Chinese population is higher than previously reported.

- Next-generation sequencing should be used in the Chinese population to increase the detection rate of carriers of Mendelian variants.

- Expanded carrier screening with next-generation sequencing should be provided to Chinese people to identify carrier status of Mendelian variants for pregnancy planning.

Introduction

Carrier screening aims to identify couples at risk

of conceiving children affected by recessive genetic

diseases. Carrier couples of most recessive genetic

conditions are typically asymptomatic, and the

only way to identify them is by carrier screening.

If a couple are both carriers of the same autosomal

recessively inherited condition, their offspring have a 1 in 4 chance of being affected. The risk is as high as

1 in 2 in male offspring if the mother is an X-linked

recessive carrier. Carrier screening facilitates

informed prenatal testing options such as pre-implantation

genetic diagnosis, prenatal invasive

testing, and other reproductive options such as

donor gametes and adoption for carrier couples.

Prenatal genetic diagnosis could provide parents with more information, appropriate counselling, and

preparation to take care of the child.1

Various carrier screening programmes

targeting specific populations have been developed

for single gene diseases such as cystic fibrosis,

thalassaemia, and Tay-Sachs disease.2 3 The

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

(ACOG) published guidelines on ethnically based

carrier screening programmes, eg, screening for

haemoglobinopathies in individuals of Southeast

Asian, African and Mediterranean descent and

screening for cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs disease,

familial dysautonomia, and Canavan disease for

individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.2 4 However,

race and ethnicity can only be determined by patient

self-report, and measures to ascertain ethnicity

are restrictive.5 Ancestry-based screening could

also lead to unequal distribution of genetic testing

and may miss diagnosis of diseases in populations

without screening.3 Thus, both the American College

of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and

ACOG recommended carrier screening for cystic

fibrosis in all couples in 2001.6 7 The ACMG and

ACOG have also recommended carrier screening for

spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in all couples since

2008 and 2017, respectively.8 9

With advancements in genomic technology

providing access to next-generation sequencing

(NGS), expanded screening panels that cover a wide variety of disorders could be offered to individuals

regardless of ethnic background.9

The common mutations in the screening panel

are mainly chosen based on studies performed in the

Caucasian and Ashkenazi Jewish populations. Those

known common mutations may not be ethnicity-specific

and may not cover all mutations present

in the Chinese population. Thus, the approach of

sequencing the entire disease-causing gene would be

more useful than the targeted common mutations

approach for the Chinese population.

Studies that evaluate carrier frequencies and

common mutations in the Chinese population are

lacking in our locality. Further study to review carrier

frequency and the identified variants in the Chinese

population is essential to guide the future design of

carrier screening platforms specific to the Chinese

population and improve the cost-effectiveness of

carrier screening for genetic diseases.

Methods

Subjects

Expanded carrier screening testing was offered to

women who attended the subfertility clinic and

pre-pregnancy counselling clinic of the study unit

between March 2016 and March 2017. They were

counselled about the prevalence and inheritance

of recessive conditions, and the chance of having

affected offspring for a silent carrier couple, using

examples and figures. The purpose, testing methods,

interpretation of results, potential benefits, risks,

and limitations of the expanded carrier screening

were also explained.

A generic consent form for the expanded

carrier screening testing prepared by the laboratory

was used. Consent for the use of data obtained

for research or audit purposes was also obtained.

The test was then ordered by the clinician as self-financed

testing. The expanded carrier screening

test was offered to both members of the couple

separately during pre-test counselling. During post-test

counselling, if a woman was identified to be a

carrier of an autosomal recessive disease, but her

partner had not completed the test, her partner was

also counselled for carrier testing using the same

method as self-financed testing. If both the male and

female members of the couple were carriers of a same

autosomal recessive disorder or the female was the

carrier of an X-linked recessive disorder, they were

identified as at-risk couples having the possibility

of an affected pregnancy. Genetic counselling was

arranged for at-risk couples to discuss reproductive

options such as preimplantation genetic testing

and prenatal diagnostic testing. Finally, the carrier

frequencies of individual diseases and the identified

variants were reviewed. STROBE reporting

guidelines were implemented in this manuscript.

Disease panels

The expanded carrier screening panel consisted of

104 conditions inherited in autosomal recessive or

X-linked manner (online supplementary Appendix).

The severity of these conditions ranged from

debilitating diseases with neurological impairment

(eg, SMA), reduced lifespan (eg, thalassaemia), or

intellectual disability (eg, fragile X syndrome) to

diseases requiring early intervention in the prenatal

or early neonatal period (eg, 21-hydroxylase deficient

congenital adrenal hyperplasia [CAH]).

Laboratory tests

The screening platform (Family Prep Screen 2.0;

Counsyl, South San Francisco [CA], United States),

which was reported by Lazarin et al,10 uses NGS

techniques to analyse the listed exons, as well as

selected intergenic and intronic regions, of the

genes responsible for the recessive conditions. The

selected regions were sequenced to high coverage

and compared with standards and references of normal

variation. High-throughput sequencing detects

approximately 94% of known clinically significant

variants according to the test provider. Variants

classified as ‘predicted’ or ‘likely’ pathogenic have

been reported.11 Fragile X specific polymerase chain

reaction assay was used to determine the CGG

repeat size in the 5' untranslated region of the FMR1

gene. Targeted copy number analysis was used to

determine the copy number of exon 7 of the SMN1

gene. g.27134T>G variant testing for identification of

silent SMA carriers is not included in this platform.12

The turnaround time of the test was approximately

3 weeks.

Results

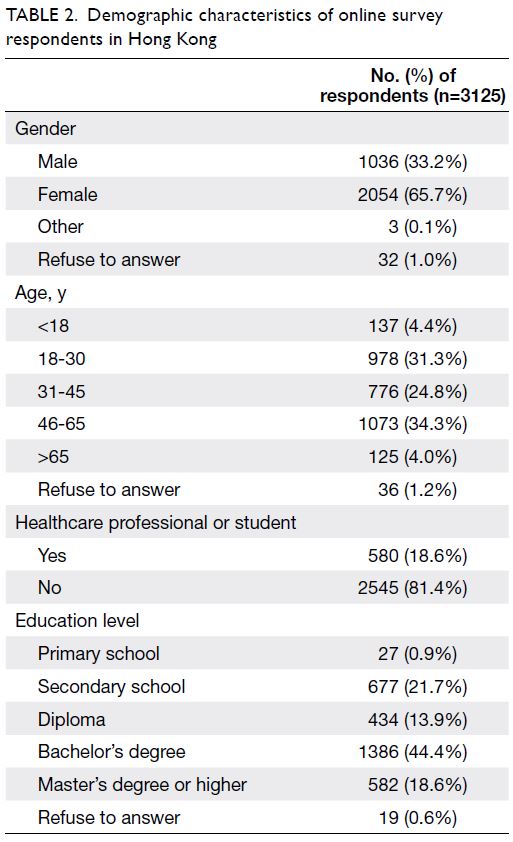

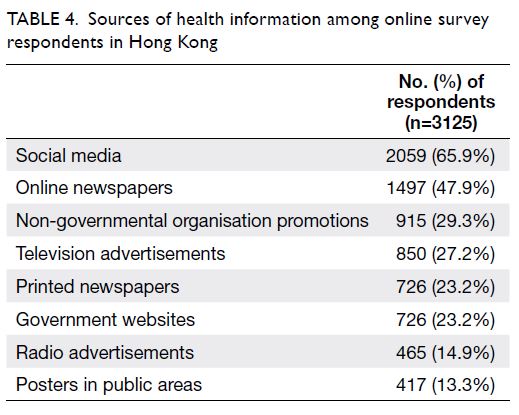

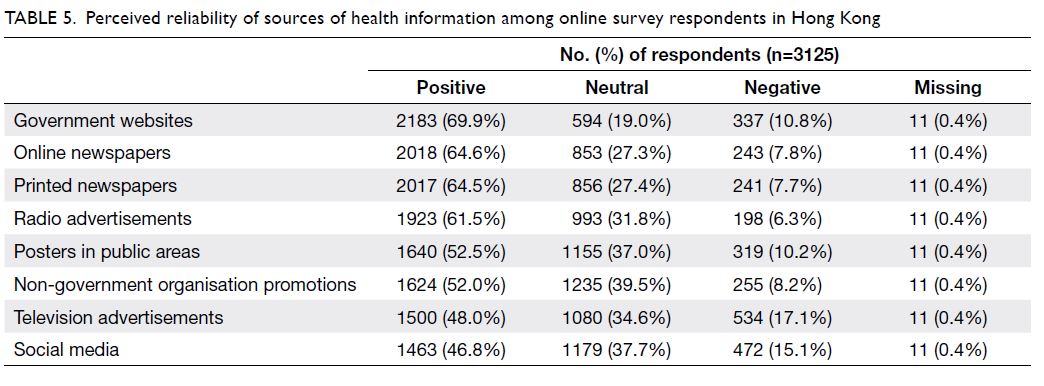

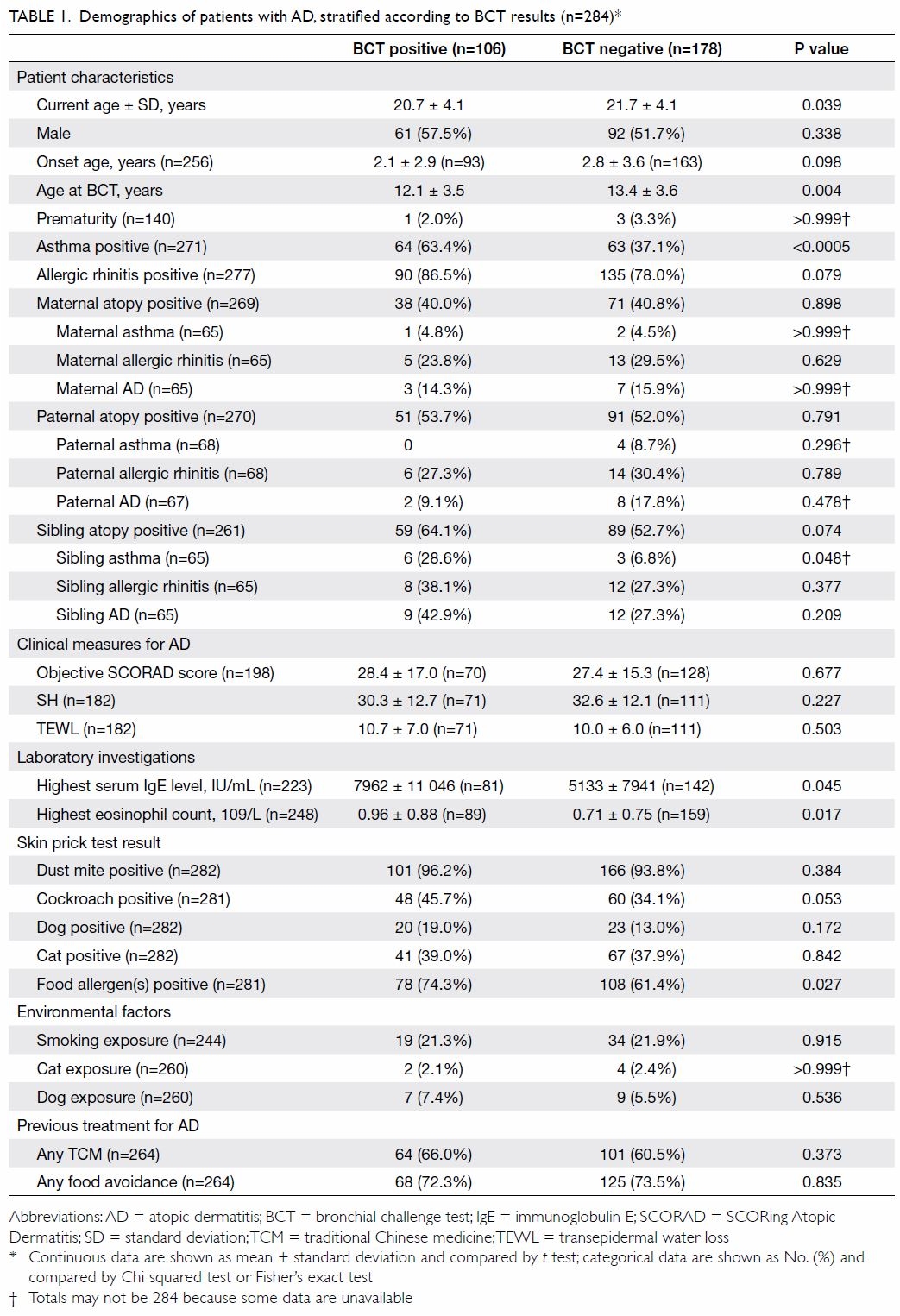

A total of 123 Chinese women (age range, 20-45 years)

opted for expanded carrier screening, and 69 (56.1%)

of them were found to be carriers of at least one

disease. Twenty of the women’s partners (29.0%,

20/69) were willing to complete the screening test

after genetic counselling. Screening for possible

carrier status before contemplating pregnancy was

the indication in all individuals. Excluding one

woman who was positive for fragile X syndrome,

48 women who screened positive opted not to

screen their partners. Seventeen of them were solely

carriers of alpha- or beta-thalassaemia (10 and 7, respectively), which could be accurately screened

by mean corpuscular volume. The results also

included 20 GJB2 carriers, especially the c.109G>A

(p.Val37Ile) mutation, which has low penetrance and

is prevalent in the Chinese population.13 14 Carrier

status for CAH, SMA, Pendred’s syndrome, and

other very rare diseases was found in three, one, one,

and six individuals, respectively. After integrating

partners’ data, 84 subjects (58.7%) were found to be

carriers for at least one recessive disease, including

thalassaemias. Excluding thalassaemias, 68 subjects

(47.6%) were found to be carriers of at least one

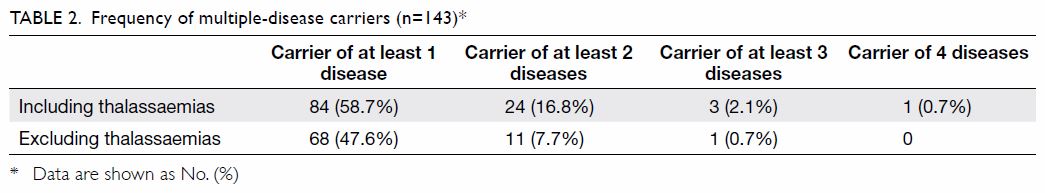

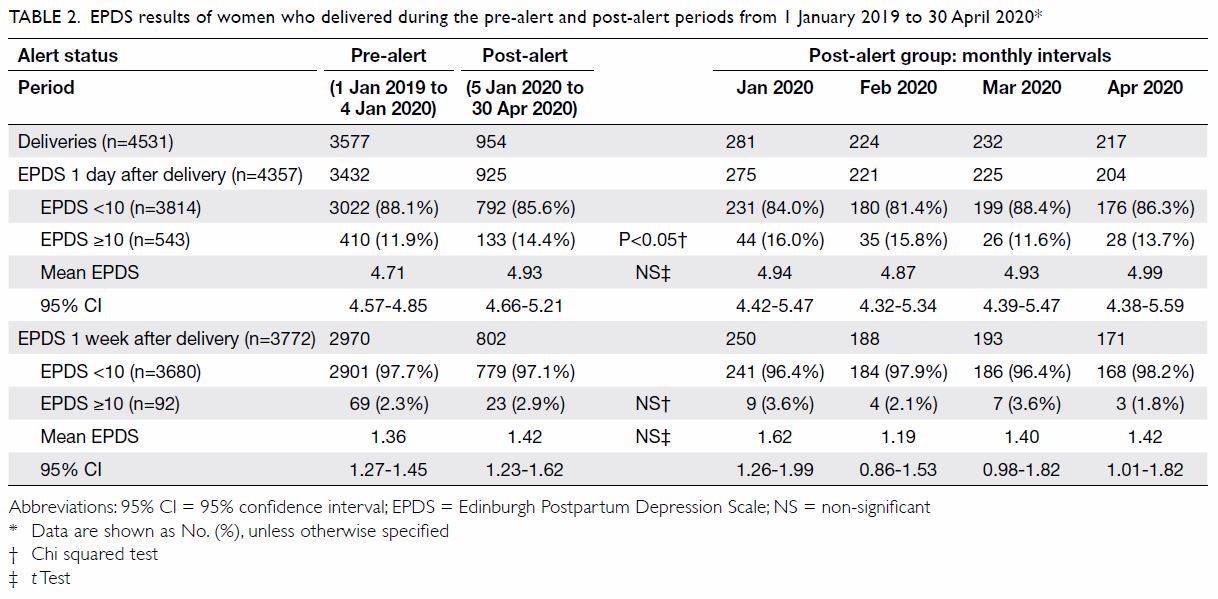

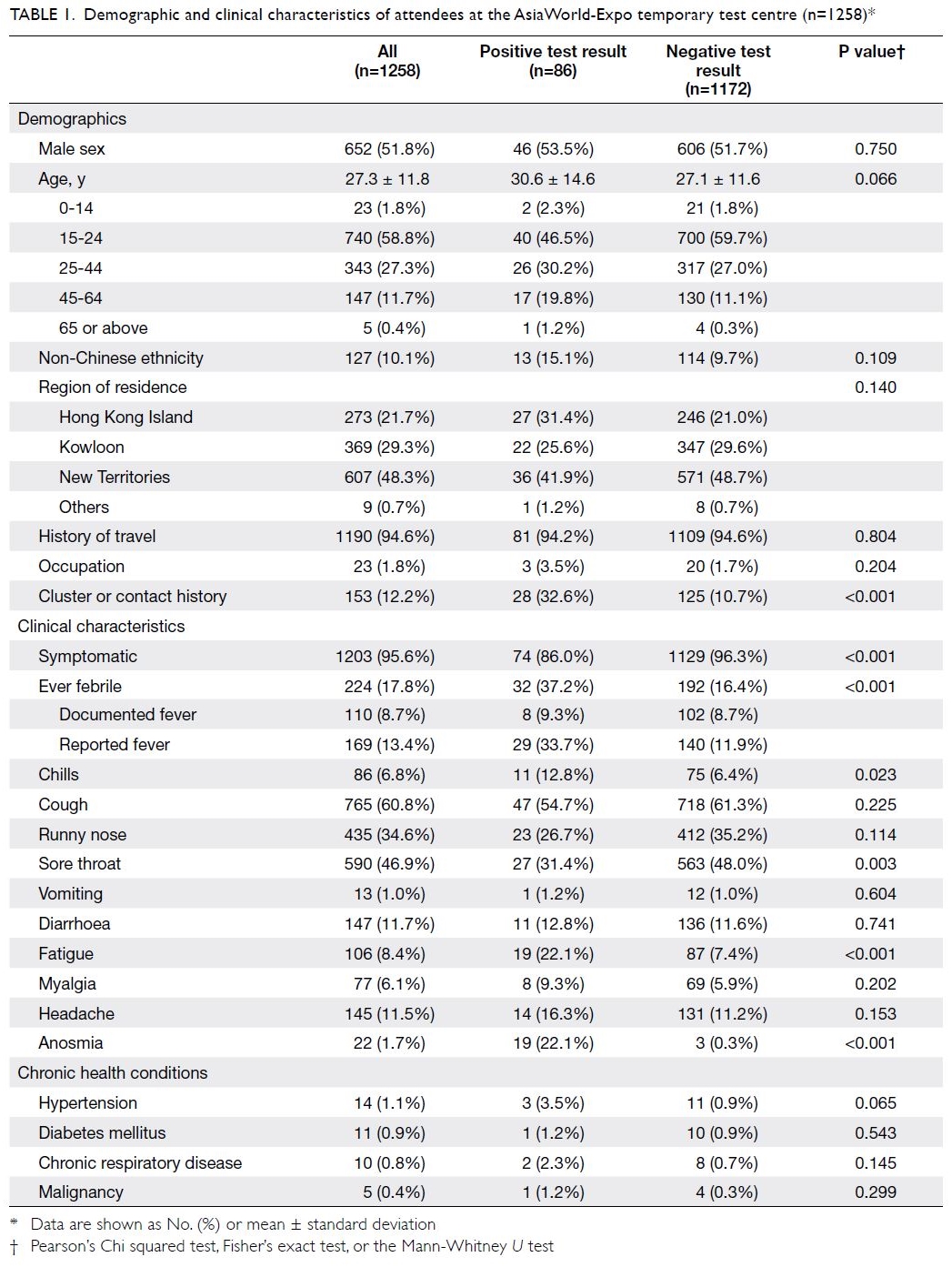

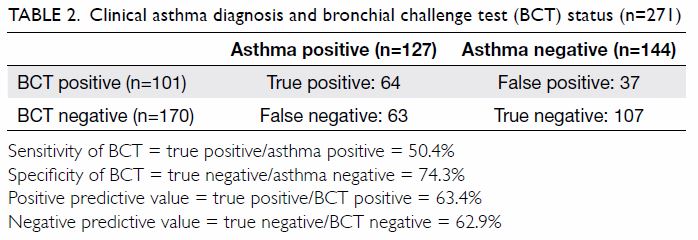

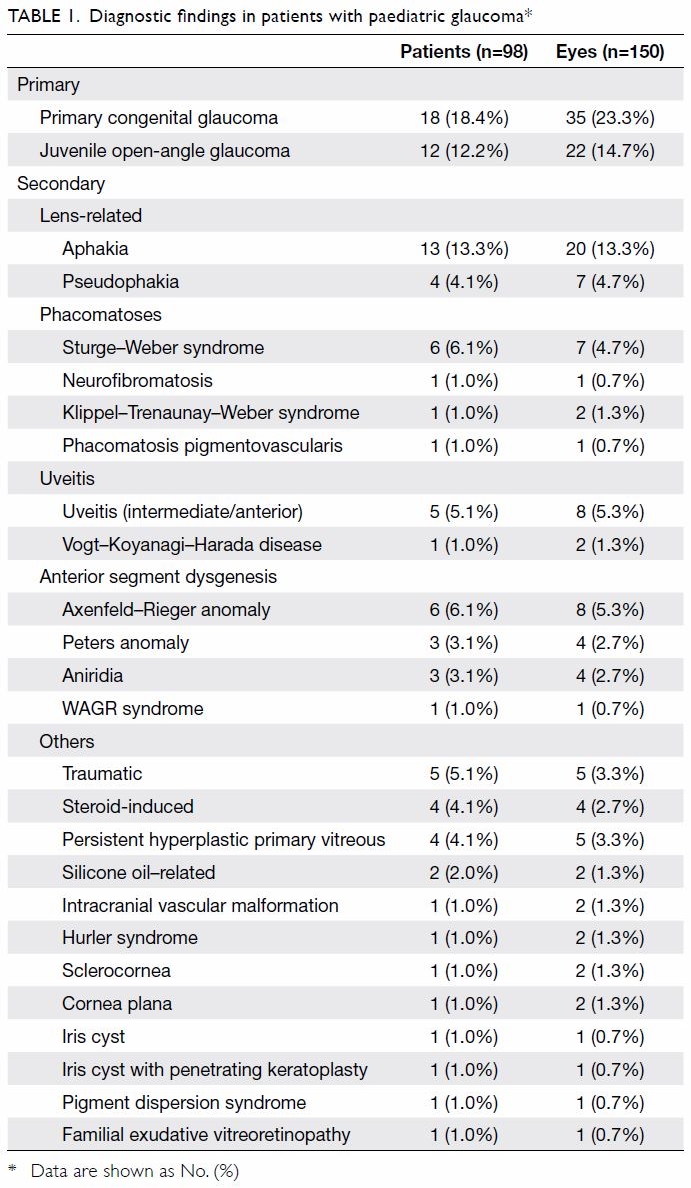

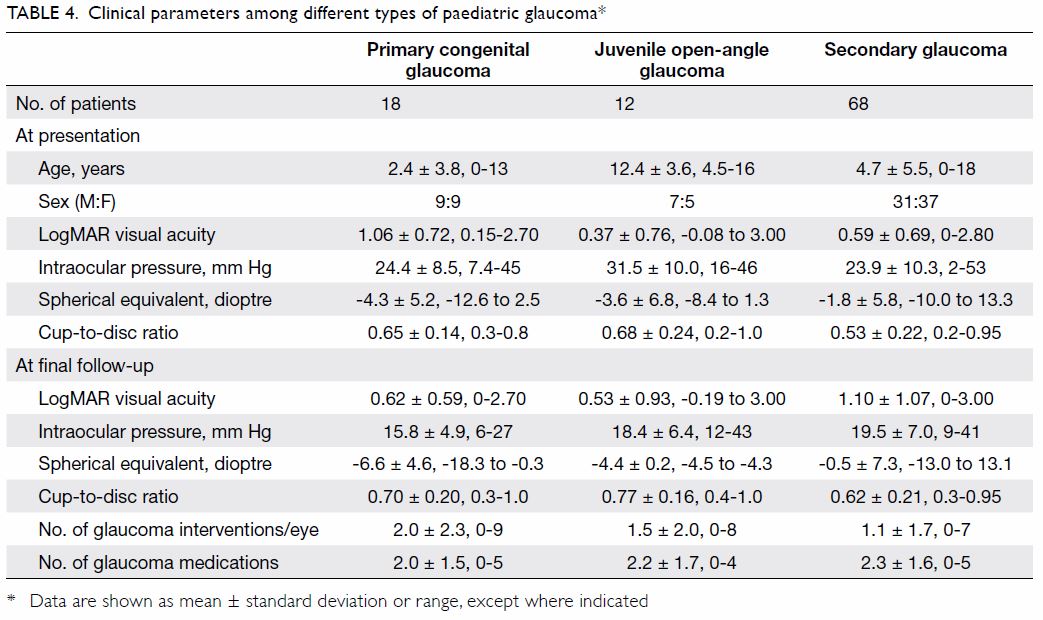

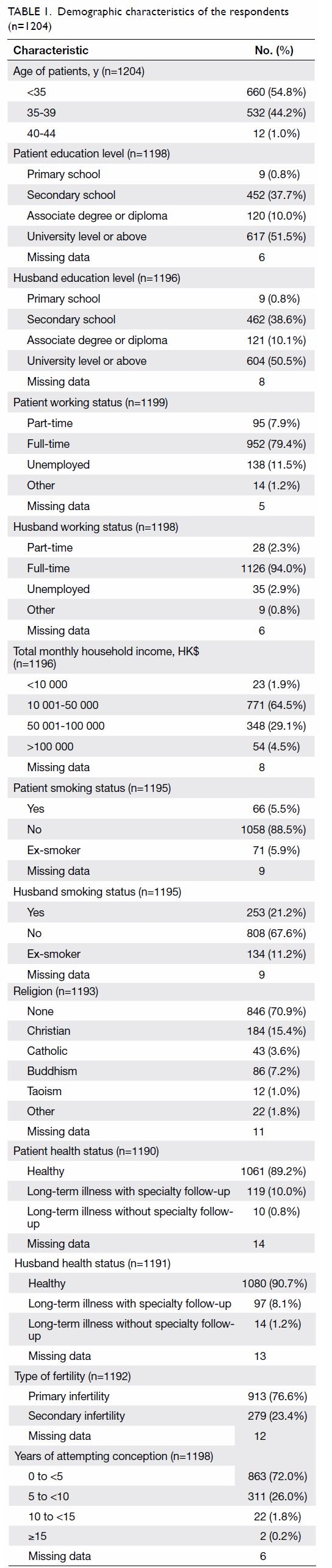

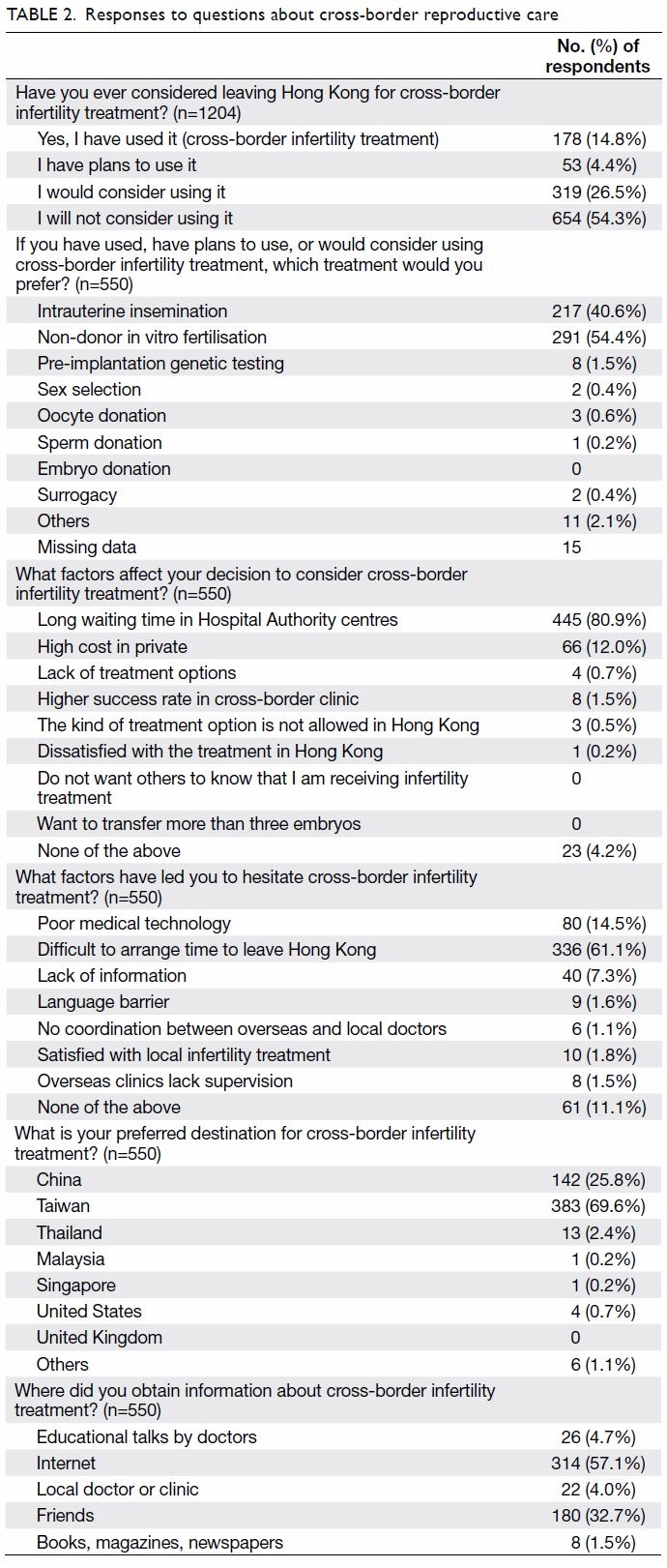

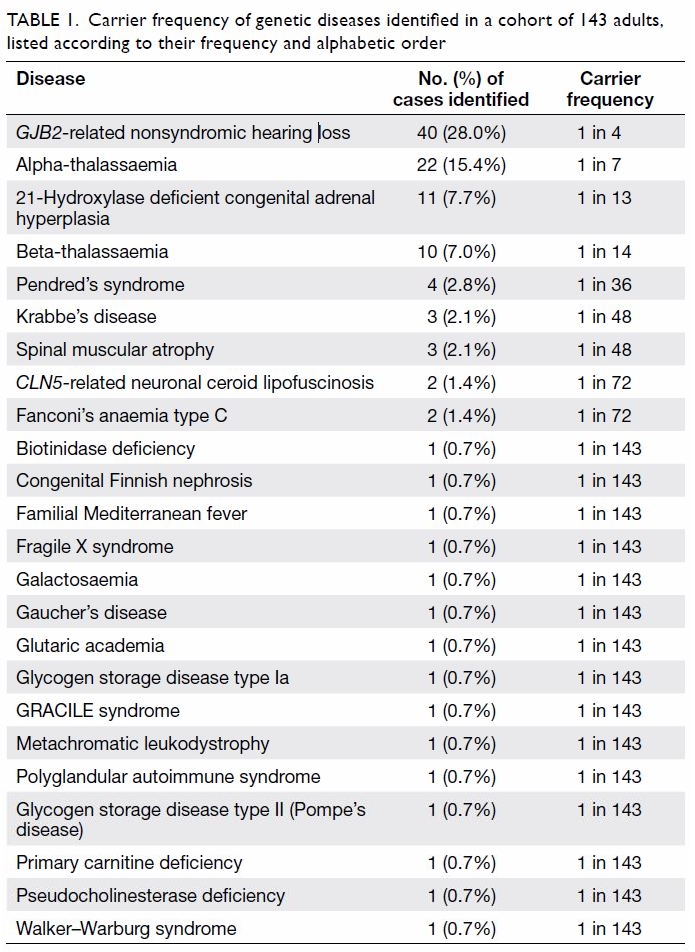

disease (Tables 1 and 2).

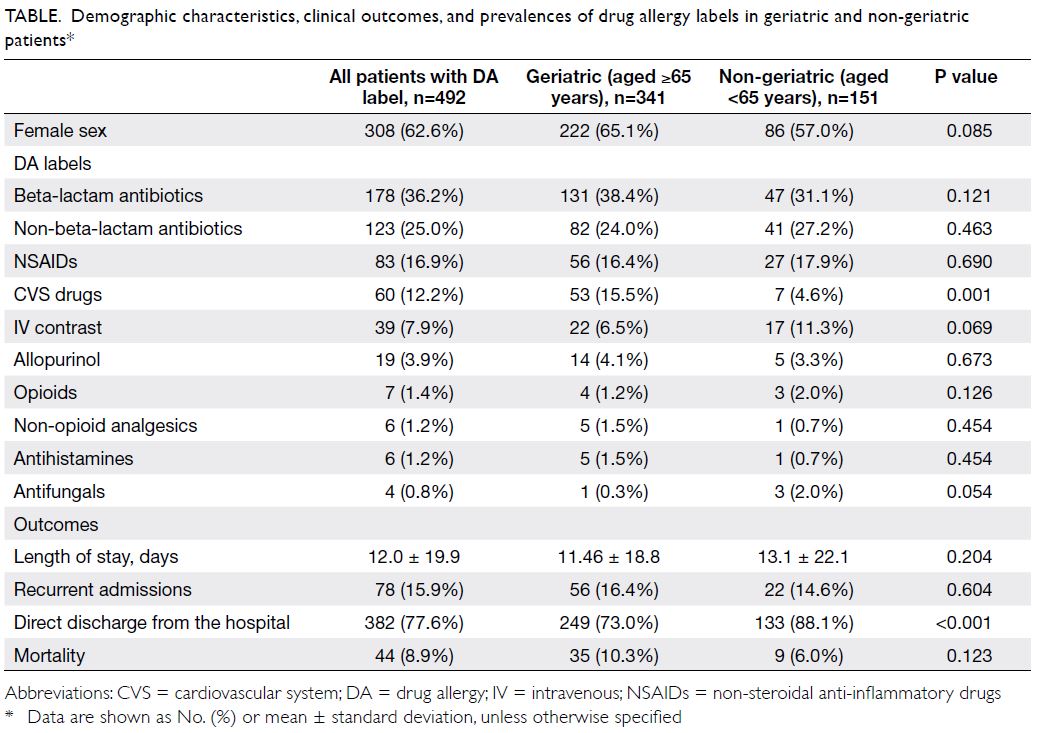

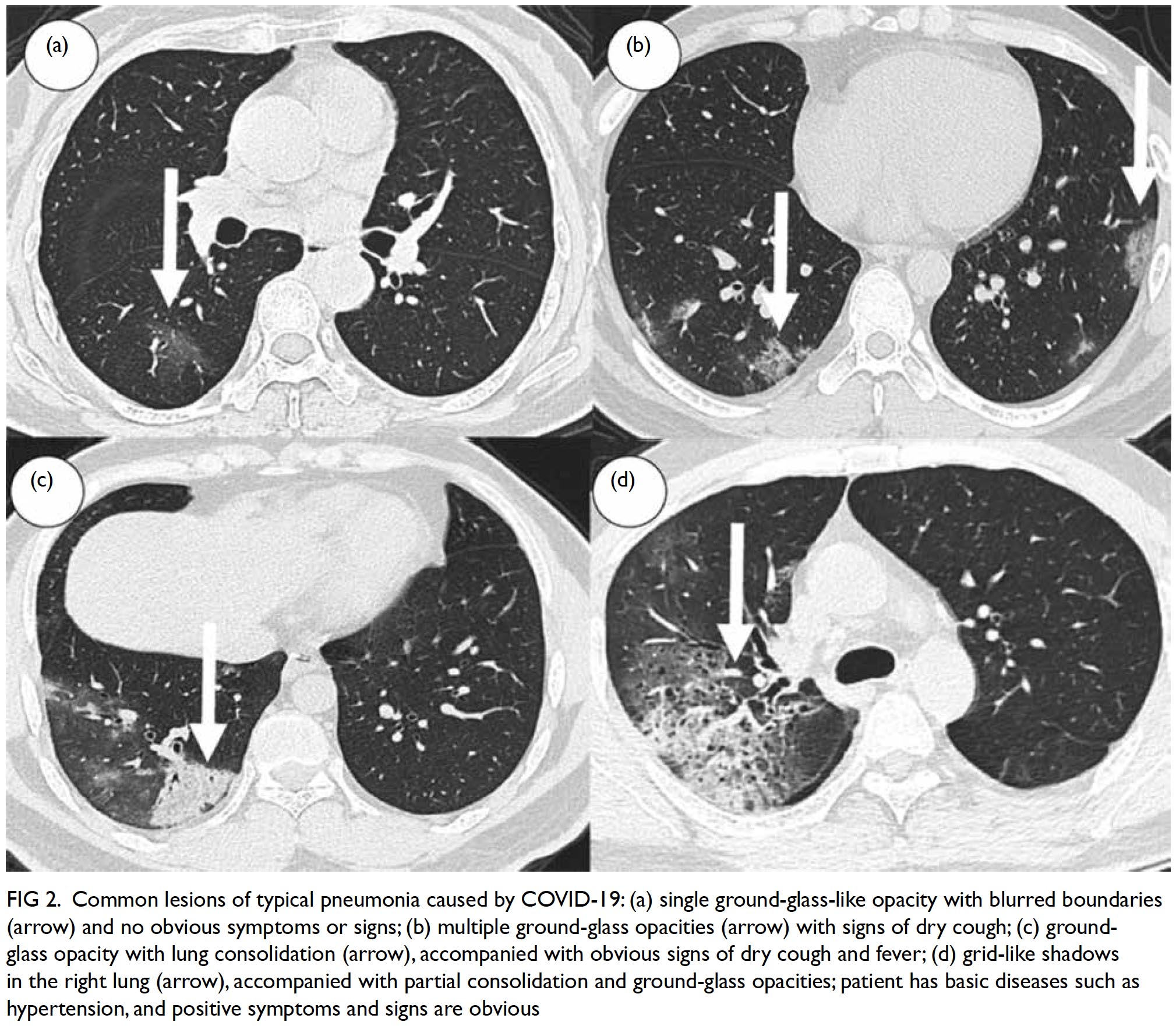

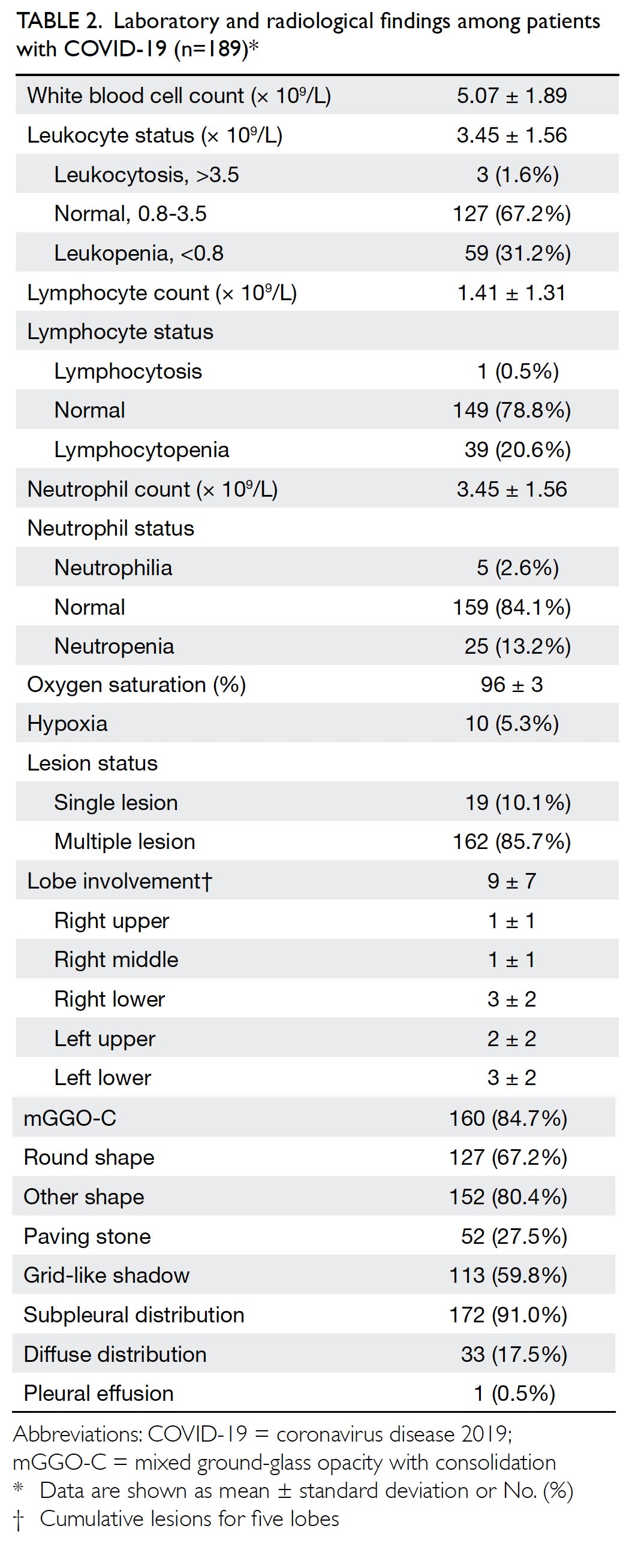

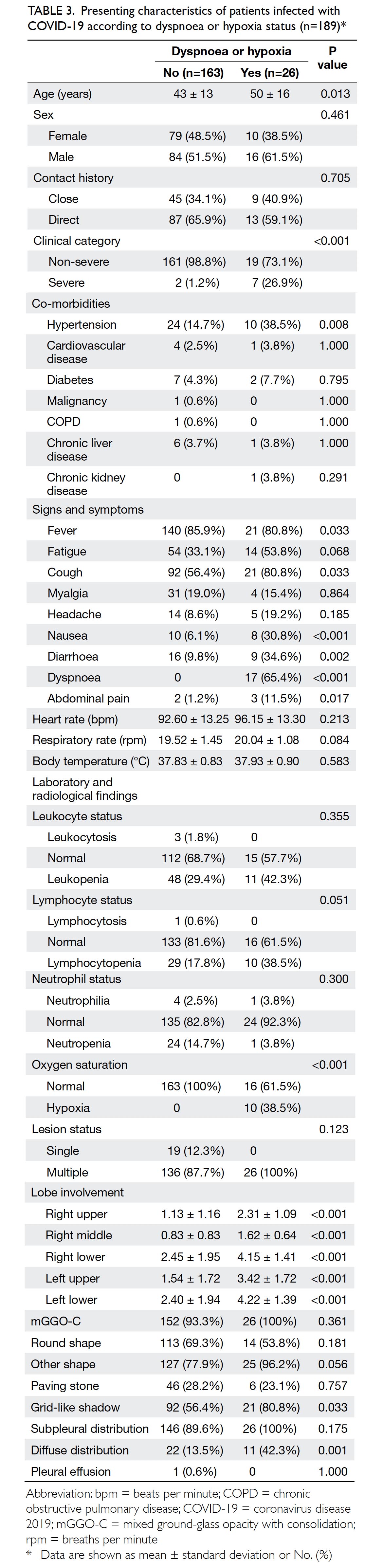

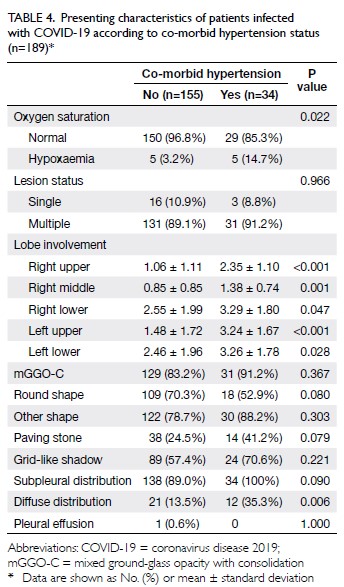

Table 1. Carrier frequency of genetic diseases identified in a cohort of 143 adults, listed according to their frequency and alphabetic order

Prevalence of carriers of various diseases

A total of 24 recessive diseases were identified in 84

(58.7%) of the 143 subjects. The data are summarised

in Table 1. The most common condition identified

was GJB2-related hearing loss (frequency: 1 in 4).

One subject was also found to be a homozygote for

the p.V37I mutation in the GJB2 gene. The subject

was aged 34 years and did not complain of hearing

impairment at the time of recruitment. Both alpha- and

beta-thalassaemia were prevalent in this cohort

(1 in 7 and 1 in 14, respectively), as shown in Table 1.

Eleven subjects (1 in 13) were identified as carriers

of the 21-hydroxylase deficient type of CAH. Four

subjects were heterozygous carriers of Pendred’s

syndrome (1 in 36), and three subjects were

heterozygous carriers for each of SMA and Krabbe’s

disease (1 in 48). Two carriers were identified for

both CLN5-related neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis

and Fanconi’s anaemia type C, and one carrier was

identified for each of 15 other recessive conditions

(Table 1).

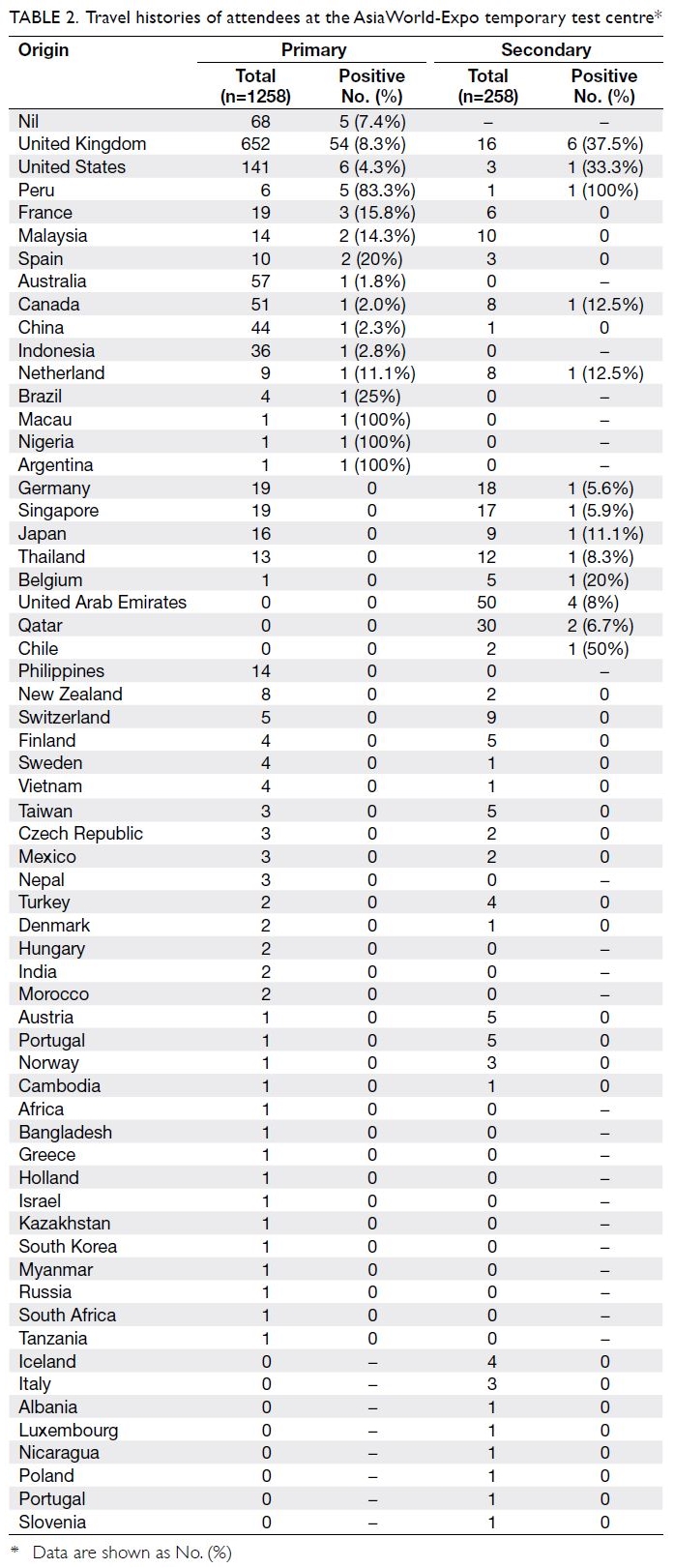

Multiple-disease carriers

The frequency of multiple-disease carriers is shown

in Table 2. Carrier status of at least two recessive

conditions was identified in 24 subjects (24/143,

16.8%) including thalassaemias and 11 subjects

(7.7%) excluding thalassaemias.

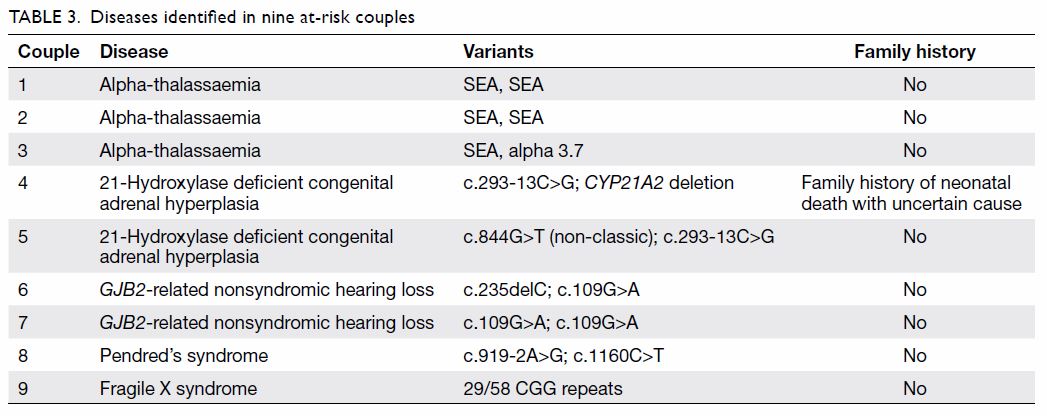

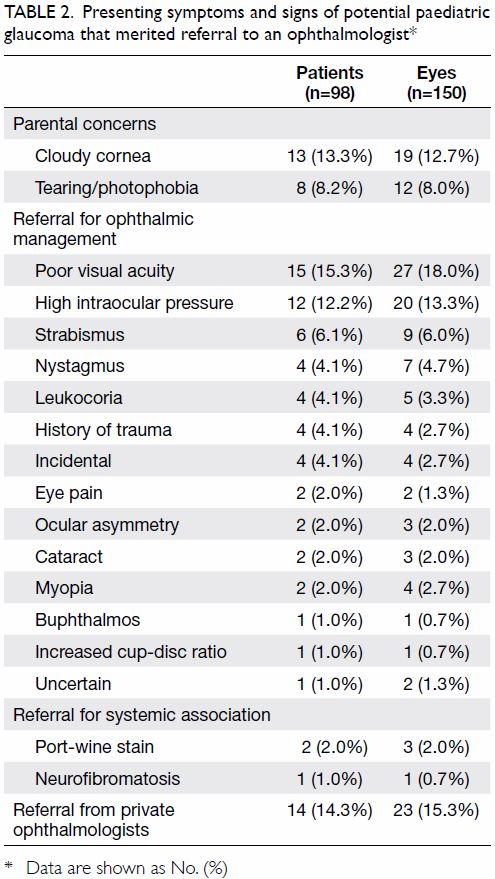

At-risk couples

One woman was a fragile X syndrome premutation

carrier, and 20 women had positive results for

carrier status, and their male partners were

sequentially tested. After integrating the sequential

testing results, we identified nine at-risk couples,

including three of alpha-thalassaemia, two of CAH,

two of GJB2-related hearing loss, one of Pendred’s

syndrome, and one of fragile X syndrome (Table 3).

The rate of at-risk couples was 12.0% (9/75) overall

and 8.0% (6/75) excluding thalassaemias.

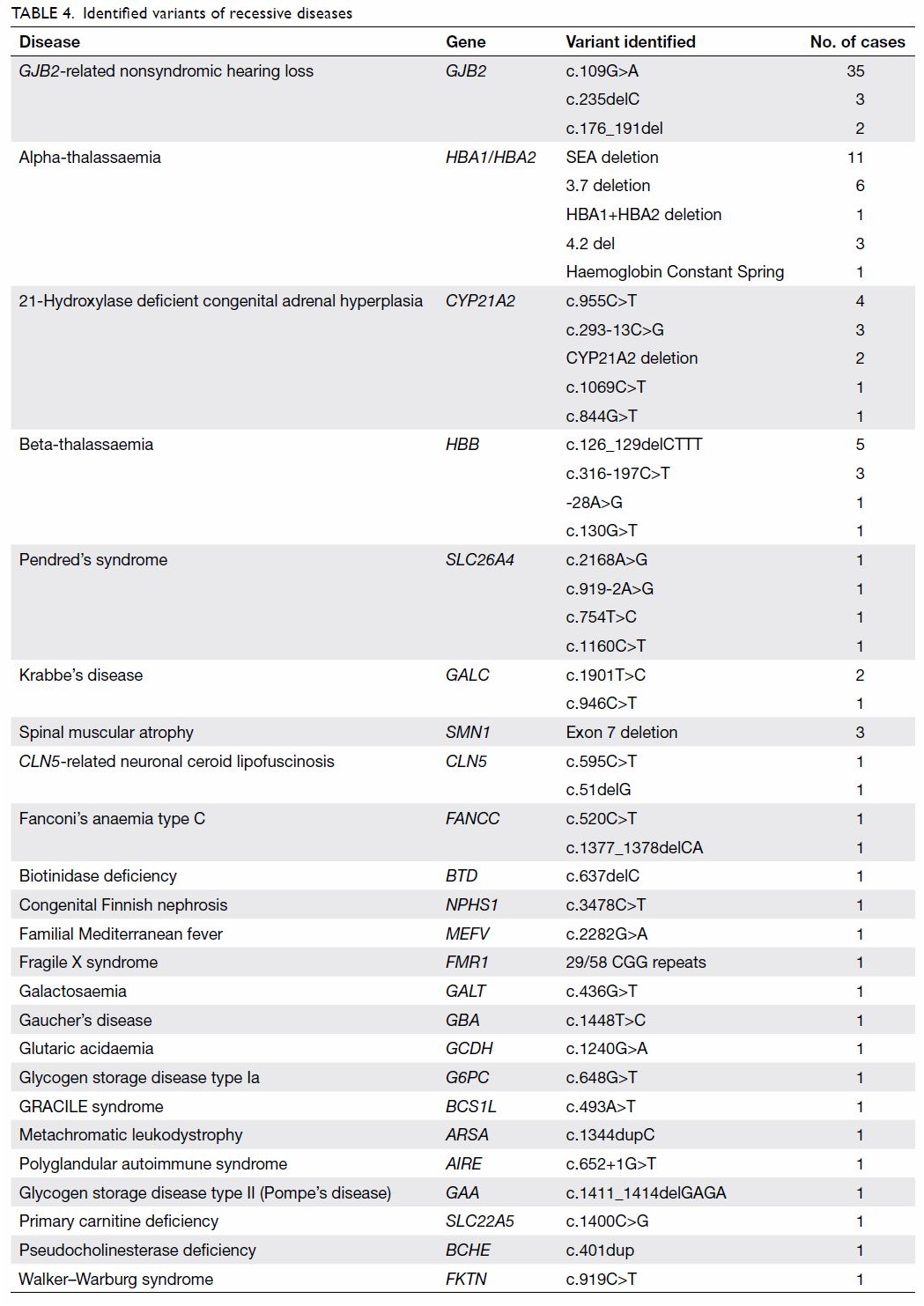

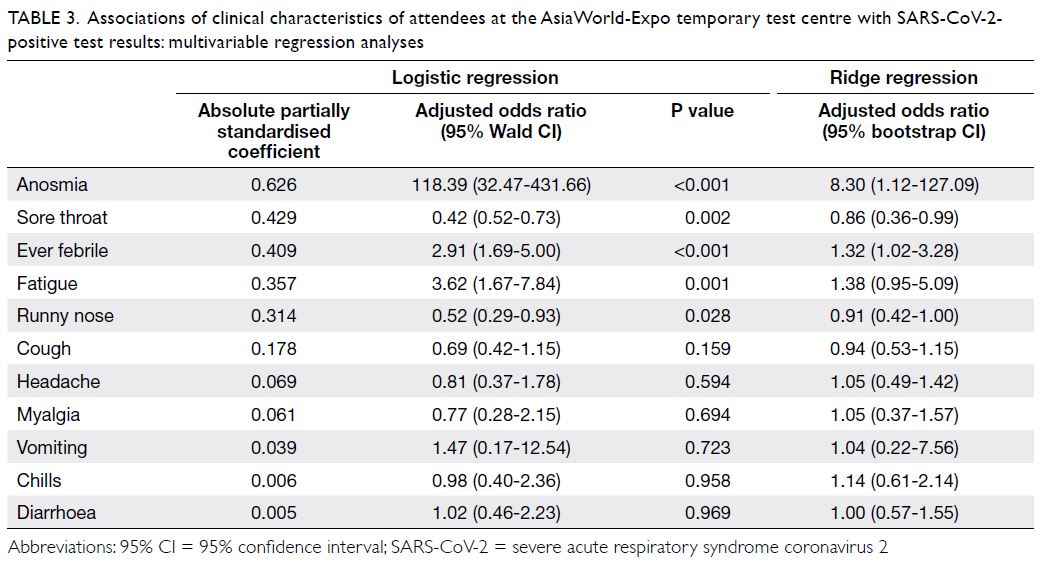

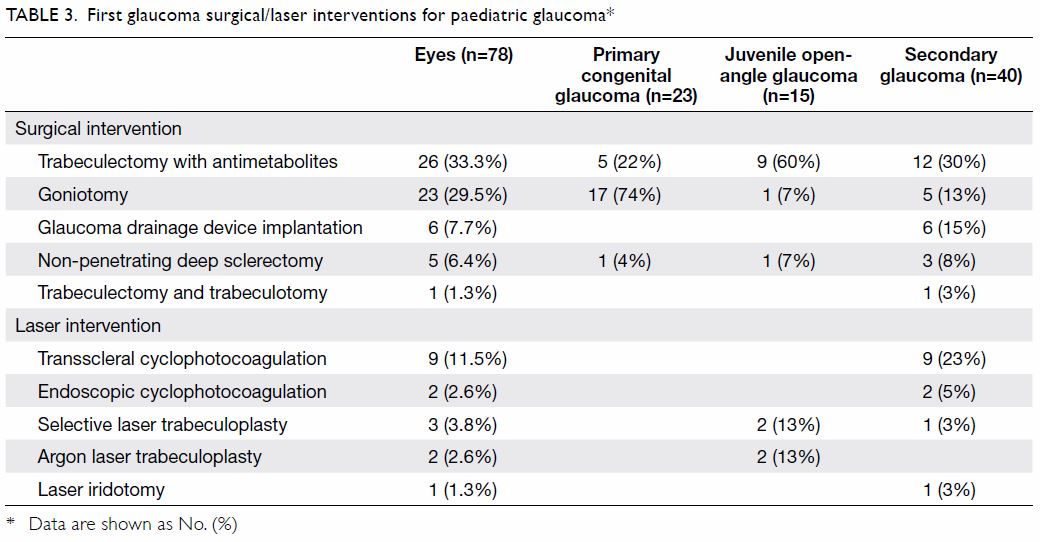

Comparison between traditional screening

guidelines and next-generation sequencing

Forty three variants were identified by the NGS

panel (Table 4). Of the 43 variants, 29 (67.4%) were

not included in the ACMG or ACOG guidelines.9 11

Discussion

This study demonstrated the application of NGS to

investigate carrier frequency status of members of

the Chinese population in Hong Kong. The overall

positive yield of this expanded carrier screening

panel in our cohort was 58.7%. Not surprisingly,

both alpha- and beta-thalassaemia account for a

significant proportion of them. However, even after

excluding thalassaemias that could be screened by

mean corpuscular volume, the positive yield using

NGS was still as high as 47.6%, with 6 out of 75 at-risk

couples (8.0%) identified and potentially benefiting

from further pre-conception genetic counselling.

Although NGS has been increasingly used

for genetic carrier screening in Western countries

in recent years, there is a scarcity of data about the

carrier frequency of various recessive diseases

in the Chinese population. In 2013, Lazarin et al10

reported the carrier frequencies of a sample of

approximately 20 000 people from different ethnic

groups using a targeted mutation panel. East Asians

had the lowest carrier frequency (8.5%) compared

with Ashkenazi Jews (43.6%) or Caucasians (21%-32.6%). The most common genetic disease identified

among East Asians was GJB2-related hearing loss

(1 in 22), followed by beta-thalassaemia/sickle cell

disease (1 in 78) and SMA (1 in 85). However, the

assay used by Lazarin et al10 was partially based on

targeted genotyping, so carriers of variants other

than the included common mutations were not

detected. Thus, the reported carrier frequencies

are likely underestimated, particularly among East

Asians, as the common mutation panel was mainly

based on the Caucasian and Ashkenazi Jewish populations. In particular, alpha-thalassaemia and

CAH are not included in their panel.

Recently, Guo and Gregg15 investigated the carrier prevalence of 415 recessive diseases using

an exome sequencing database of approximately

120 000 samples. The consistent finding is that Ashkenazi Jews had the highest carrier frequency

(62.9%), followed by Caucasians, Africans, and

Hispanics; South and East Asians had the lowest

carrier frequency, but that frequency rose to 32.6%

with a more comprehensive panel. However, because

neither alpha-thalassaemia nor SMA was included

in the panel, the most common diseases for which

carrier status was found among East Asians were

autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1,

beta-thalassaemia, Usher’s syndrome type IIa, and

CAH. The carrier frequency of each of those diseases

was 1% to 2%. In 2018, Zhao et al16 reported >10 000

mainland Chinese couples in whom NGS was used

to screen for 11 recessive diseases. That study

showed a high carrier frequency of 27.49%, and 2.4%

of couples were carriers of the same genetic disease.

The authors found that the diseases with the highest

carrier frequencies were alpha-thalassaemia (15.1%),

beta-thalassaemia (4.8%), phenylketonuria (3.6%),

Wilson’s disease (2.0%), GJB2-related hearing loss

(1.7%), and Pendred’s syndrome (1.6%). However,

that study excluded SMA, CAH, and fragile X

syndrome.16 Our study’s findings are distinguished

from those of Lazarin et al,10 Guo and Gregg,15 and

Zhao et al16 in that we observed a much higher carrier

rate for GJB2-related hearing loss (28.0%), which is

consistent with our previous report (15.9%) using

target-enriched massively parallel sequencing.14 In

addition, we found higher carrier frequencies for

CAH (7.7%) and Pendred’s syndrome (2.8%). Our

study observed carrier frequency for SMA (2.1%)

is similar to that found in Western populations,17 18 19 20 21

indicating that SMA affects all ethnic groups.

One of the major limitations of our study was

the small sample size. More data are required before

we can draw precise conclusions regarding the carrier

frequency of individual recessive conditions

in the Chinese population. Second, patients in this

cohort were referred for subfertility or pre-pregnancy

counselling for genetic conditions, and give out of

this 123-patient cohort had a positive family history,

including thalassaemias, balanced translocation

carriers, family history of autism, neonatal death,

and previous pregnancy with structural abnormality.

Thus, some of the results might have been over-represented.

For example, one woman who presented

with subfertility was discovered to be a fragile X

permutation carrier, and this may have elevated

the carrier frequency of fragile X in our cohort of

123 women. In our previous study, in which we used

a robust polymerase chain reaction–based assay to

quantify fragile X CGG repeats for screening of 3000

low-risk Chinese pregnant women, the permutation

frequency was approximately 1 in 800.22 Another

couple in the present study had a previous baby with

neonatal death of unknown cause in Mainland China

and were found to be 21-hydroxylase deficient CAH carriers. Nonetheless, even after excluding these two

CAH cases, the CAH carrier frequency in our study

(1 in 16) remains high.

Currently, both the ACOG and ACMG

recommend carrier screening for SMA and cystic

fibrosis only in individuals of East Asian ethnicity.7 9

If those ethnic-based carrier screening strategies

advocated by the guidelines had been followed,

many carriers and all five carrier couples identified

in our cohort would have been missed. The results

of our pilot study suggest that recessive genetic

conditions may not be as uncommon as previously

thought. Many of the diseases identified in our

cohort are debilitating conditions that are associated

with progressive neurological derangement and

reduced life span, such as SMA, Krabbe’s disease,

and biotinidase deficiency. More importantly, some

conditions such as CAH may require intervention

during the early prenatal or early neonatal periods to

avoid irreversible complications. Hence, public and

professional awareness of expanded carrier screening

should be improved, and genetic counselling and

expanded carrier screening should be an option for

the Chinese population, especially in the setting of

subfertility clinics.

Yet, genetic carrier screening has not been

popular among the Chinese population or in Hong

Kong because of the high cost of the test and the

perceived low carrier rate in Chinese people. As the

cost for NGS has dropped recently, and our pilot

study demonstrated an overall high yield of 8.0% of

couples at risk of conceiving foetuses with genetic

diseases (even after excluding thalassaemias), further

studies of couples are warranted. Potential candidates

for expanded carrier screening in Hong Kong also

include couples in consanguineous marriages, which

are common in minor ethnic groups such as Pakistani

and Indian. A recent local study showed that they

had a higher prevalence of congenital abnormality

(10.5%), unexplained intrauterine foetal demise

(4.2%), and unexplained neonatal death (4.6%).23

In our cohort, NGS was used to analyse the

listed exons, as well as selected intergenic and intronic

regions, of the genes responsible for certain recessive

conditions. The high-throughput sequencing

technique was able to detect approximately 94% of

known clinically significant variants irrespective

of ethnicity. Of 43 variants identified using NGS,

29 (67.4%) were not included in the ACMG or ACOG

guidelines. Thus, our study demonstrated that the

NGS technique increased the detection rate of

carrier status for recessive conditions in the Chinese

population. Yet, further study with a larger sample

size should be conducted to study the prevalence of

carrier status, which conditions should be included,

and ethical issues related to carrier screening testing

such as reproductive options.

Conclusion

The observed carrier frequency in the Chinese

population was 58.7% overall (47.6% after excluding

thalassaemias) and was higher than previously

reported. Expanded carrier screening using NGS

should be provided to Chinese people to improve the

detection rate of carrier status and facilitate optimal

pregnancy planning.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the

study, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research project was partially funded by the Liauw’s Family Reproductive Genomics Programme.

Ethics approval

This study obtained ethical approval from The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kongew Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref CREC2019.138). All

participants gave informed consent before the study.

References

1. Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded

carrier screening in reproductive medicine-points to

consider: a joint statement of the American College of

Medical Genetics and Genomics, American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of

Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol

2015;125:653-62. Crossref

2. ACOG Committee on Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin

No. 78: hemoglobinopathies in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol

2007;109:229-37. Crossref

3. Bajaj K, Gross SJ. Carrier screening: past, present and

future. J Clin Med 2014;3:1033-42. Crossref

4. ACOG Committee on Genetics. ACOG Committee

Opinion No. 442: preconception and prenatal carrier

screening for genetic diseases in individuals of Eastern

European Jewish descent. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:950-3. Crossref

5. Eisenhower A, Suyemoto K, Lucchese F, Canenguez K.

“Which box should I check?”: examining standard check

box approaches to measuring race and ethnicity. Health

Serv Res 2014;49:1034-55. Crossref

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. ACOG Committee Opinion No.

486: update on carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Obstet

Gynecol 2011;117:1028-31. Crossref

7. Watson MS, Cutting GR, Desnick RJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis

population carrier screening: 2004 revision of American

College of Medical Genetics mutation panel. Genet Med

2004;6:387-91. Crossref

8. Prior TW, Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee.

Carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy. Genet Med

2008;10:840-2. Crossref

9. Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 691:

carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol

2017;129:e41-55. Crossref

10. Lazarin GA, Haque IS, Nazareth S, et al. An empirical

estimate of carrier frequencies for 400+ causal Mendelian

variants: results from an ethnically diverse clinical sample

of 23,453 individuals. Genet Med 2013;15:178-86. Crossref

11. Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, Evans EA, Goldberg JD,

Wapner RJ. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified

by expanded carrier screening. JAMA 2016;316:734-42. Crossref

12. Feng Y, Ge X, Meng L, et al. The next generation of

population-based spinal muscular atrophy carrier

screening: comprehensive pan-ethnic SMN1 copy-number

and sequence variant analysis by massively parallel

sequencing. Genet Med 2017;19:936-44. Crossref

13. Shen J, Oza AM, Del Castillo I, et al. Consensus

interpretation of the p.Met34Thr and p.Val37Ile variants

in GJB2 by the ClinGen Hearing Loss Expert Panel. Genet

Med 2019;21:2442-52. Crossref

14. Choy KW, Cao Y, Lam ST, Lo FM, Morton CC, Leung TY.

Target-enriched massively parallel sequencing for genetic

diagnosis of hereditary hearing loss in patients with normal

array CGH result. Hong Kong Med J 2018;24 Suppl 3:11-4.

15. Guo MH, Gregg AR. Estimating yields of prenatal carrier

screening and implications for design of expanded carrier

screening panels. Genet Med 2019;21:1940-7. Crossref

16. Zhao S, Xiang J, Fan C, et al. Pilot study of expanded

carrier screening for 11 recessive diseases in China: results

from 10,476 ethnically diverse couples. Eur J Hum Genet

2019;27:254-62. Crossref

17. Li C, Geng Y, Zhu X, et al. The prevalence of spinal muscular

atrophy carrier in China: evidences from epidemiological

surveys. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e18975. Crossref

18. Evans M, McCarthy M, Moore R, Karbassi I, Alagia DP,

Lacbawan F. A comprehensive analysis of allele frequencies

from 476,930 spinal muscular atrophy test results [23M].

Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:147S. Crossref

19. Park JE, Yun S, Roh EY, Yoon JH, Shin S, Ki CS. Carrier

frequency of spinal muscular atrophy in a large-scale

Korean population. Ann Lab Med 2020;40:326-30. Crossref

20. Dejsuphong D, Taweewongsounton A, Khemthong P, et al.

Carrier frequency of spinal muscular atrophy in Thailand.

Neurol Sci 2019;40:1729-32. Crossref

21. Chen X, Sanchis-Juan A, French CE, et al. Spinal muscular

atrophy diagnosis and carrier screening from genome

sequencing data. Genet Med 2020;22:945-53. Crossref

22. Kwok YK, Wong KM, Lo FM, et al. Validation of a robust

PCR-based assay for quantifying fragile X CGG repeats.

Clin Chim Acta 2016;456:137-43. Crossref

23. Siong KH, Au Yeung SK, Leung TY. Parental consanguinity

in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:192-200. Crossref