Non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder in a Chinese cohort

Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):116–23 | Epub 20 Apr 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder in a Chinese

cohort

YH Ting, MB, BS, FRCOG1; PL So, MB, BS, MRCOG2; KW Cheung, MB, BS, MRCOG3; TK Lo, MB, BS, FRCOG4; Teresa WL Ma, MB, BS, FRCOG5; TY Leung, MD, FRCOG

1 Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof TY Leung (tyleung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder

(NVFGB) is associated with chromosomal

abnormalities, biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, and

gallbladder agenesis in Caucasian fetuses. We

investigated the outcomes of fetuses with NVFGB in

a Chinese cohort.

Methods: This retrospective analysis included

cases of NVFGB among Chinese pregnant women

at five public fetal medicine clinics in Hong Kong

from 2012 to 2019. We compared the incidences of

subsequent gallbladder visualisation, chromosomal

abnormalities, biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, and

gallbladder agenesis between cases of isolated

NVFGB and cases of non-isolated NVFGB.

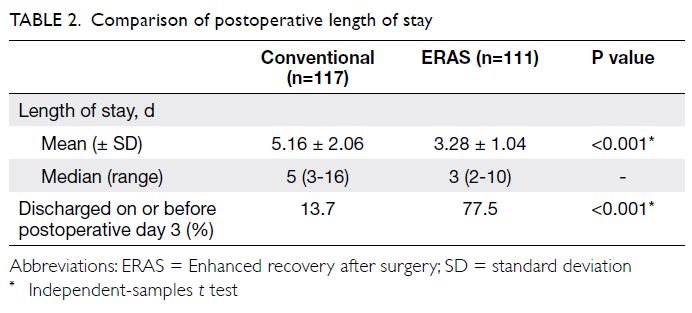

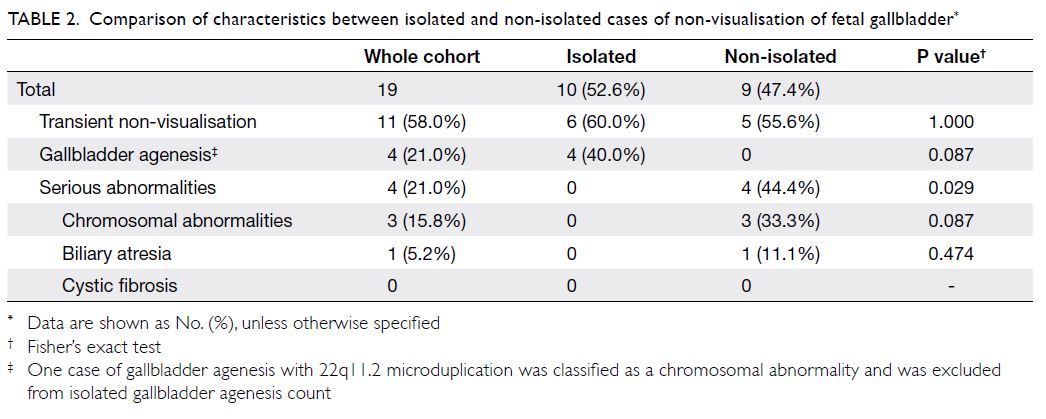

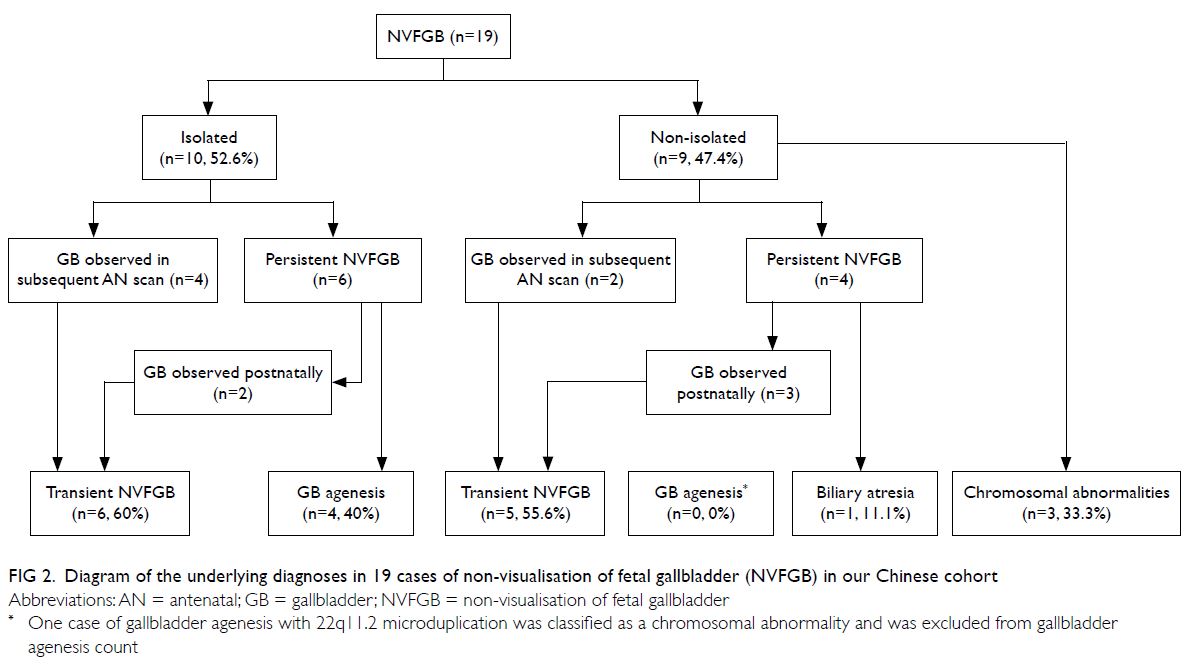

Results: Among 19 cases of NVFGB detected at a

median gestational age of 21.3 weeks (interquartile

range, 20.0-22.3 weeks), 10 (52.6%) were isolated and

nine (47.4%) were non-isolated. Eleven (58.0%) cases

had transient non-visualisation, four (21.0%) had

gallbladder agenesis, three (15.8%) had chromosomal

abnormalities (trisomy 18, trisomy 21, and 22q11.2

microduplication), one (5.2%) had biliary atresia,

and none had cystic fibrosis. The incidence of

serious conditions was significantly higher in the

non-isolated group than in the isolated group (44.4%

vs 0%; P=0.029); all three cases with chromosomal

abnormalities and the only case of biliary atresia

were in the non-isolated group, while all four cases

with gallbladder agenesis were in the isolated group. The incidences of transient non-visualisation were

similar (55.6% vs 60.0%; P=1.000).

Conclusion: Isolated NVFGB is often transient or

related to gallbladder agenesis. While investigations

for chromosomal abnormalities and biliary atresia

are reasonable in cases of NVFGB, testing for cystic

fibrosis may be unnecessary in Chinese fetuses unless

the NVFGB is associated with consistent ultrasound

features, significant family history, or consanguinity.

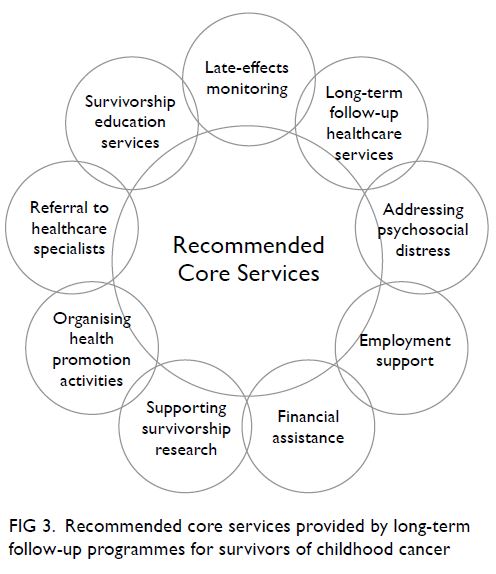

New knowledge added by this study

- Non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder (NVFGB) is associated with chromosomal abnormalities, biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, and gallbladder agenesis in Caucasian fetuses. A similar pattern of associated conditions was observed in Chinese fetuses with NVFGB, but none had cystic fibrosis.

- While the incidences of chromosomal abnormalities and biliary atresia were significantly higher in cases of non-isolated NVFGB, isolated NVFGB was generally transient or related to gallbladder agenesis; the risks of chromosomal abnormalities and biliary atresia are presumably low in cases of isolated NVFGB.

- The chromosomal abnormalities associated with NVFGB include common aneuploidies, microdeletions, and microduplications.

- Considering the association with chromosomal abnormalities, amniocentesis is recommended in cases of NVFGB. Chromosomal microarray analysis is more appropriate than karyotyping for the detection of associated microdeletions and microduplications.

- Amniotic fluid gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (AFGGT) assay may be useful because low AFGGT level is reportedly a marker for biliary atresia; it is sensitive but not specific, particularly after 22 weeks of gestation.

- Further testing for cystic fibrosis may be unnecessary in Chinese fetuses unless the NVFGB is associated with consistent ultrasound features, significant family history, or consanguinity.

Introduction

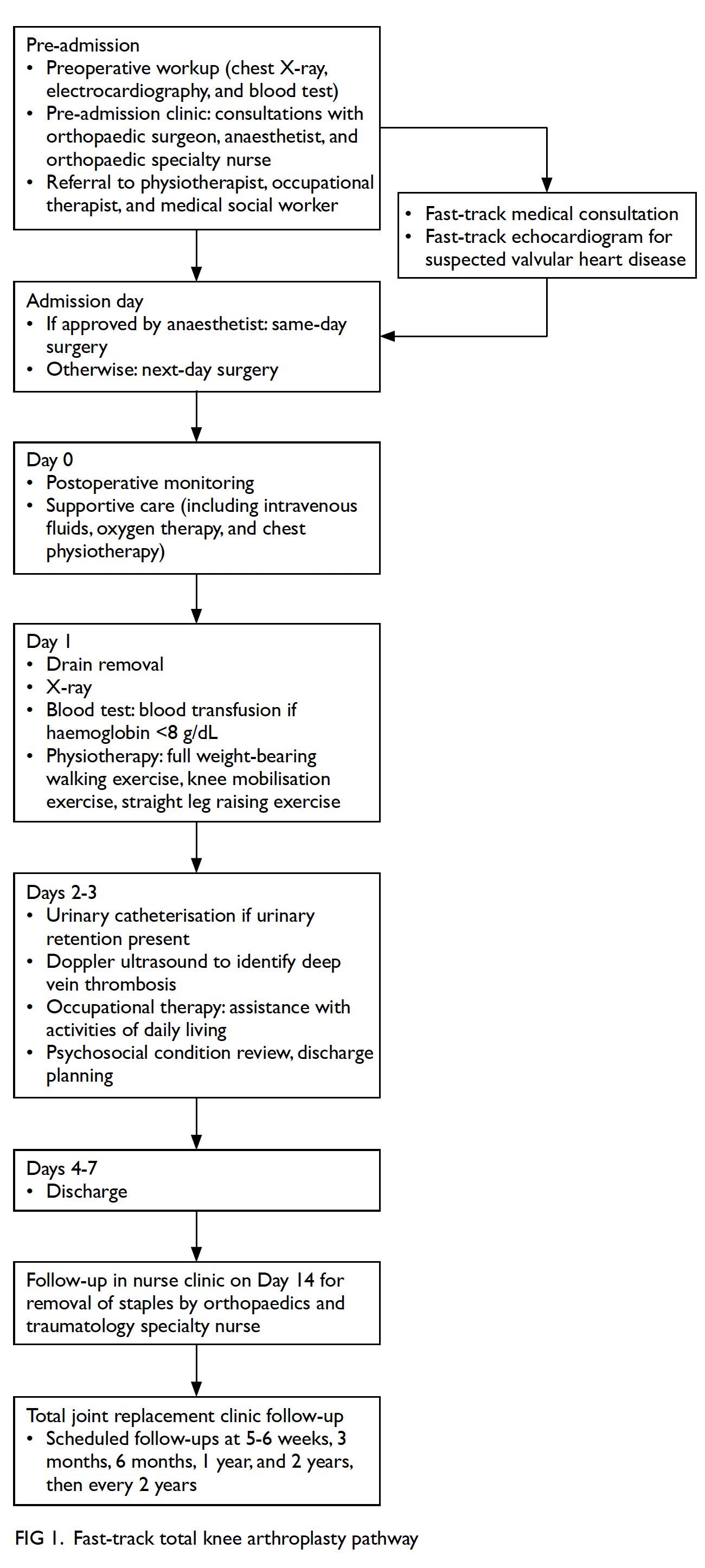

The fetal gallbladder can be observed by antenatal

ultrasound scan at 14 weeks of gestation.1 During

the morphology scan at approximately 20 weeks

of gestation, >99% of fetal gallbladders can be

observed; in 75% of cases of non-visualisation of

fetal gallbladder (NVFGB), a gallbladder is clearly

present during subsequent scans.2 However,

the visualisation rate drops to 75% to 85% after

32 weeks of gestation when the gallbladder becomes

contractile.3 4

Although sonographic examination of the

fetal gallbladder is not technically difficult, the

International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics

and Gynecology and other professional bodies

have not yet included the gallbladder as a routine

component of the mid-trimester anatomical

survey.5 6 7 8 The problem with routine examination of the fetal gallbladder is that non-visualisation of the

gallbladder can lead to challenging counselling and

antenatal diagnosis because NVFGB is related to a

wide spectrum of fetal conditions. While NVFGB

may be a transient phenomenon in a normal fetus or

the result of gallbladder agenesis (a benign congenital

anomaly), it can also be associated with more serious

underlying conditions such as biliary atresia, cystic

fibrosis, or chromosomal abnormalities. While

it is generally simple to identify chromosomal abnormalities and cystic fibrosis by amniocentesis,

the antenatal diagnosis of biliary atresia is challenging

because no diagnostic antenatal test is currently

available. Because biliary atresia can be fatal without

early postnatal intervention and may eventually

require liver transplantation, uncertainty regarding

the antenatal diagnosis of such a condition may

cause significant parental anxiety; some parents may

even consider termination of pregnancy to avoid the

risk of a severe abnormality in their child.9 10

A systematic review of isolated NVFGB in

Western populations revealed that the incidences

of transient non-visualisation, gallbladder agenesis,

biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, and chromosomal

abnormalities were 69.4%, 24.7%, 3.5%, 2.4%, and

1.4%, respectively. The incidences of biliary atresia,

cystic fibrosis, and chromosomal abnormalities

were higher in cases of non-isolated NVFGB with

additional sonographic abnormalities: 18.2%, 23.1%,

and 20.4%, respectively.11 However, the incidences

may differ considerably among Chinese women with

NVFGB, as cystic fibrosis is uncommon in Asian

populations, while biliary atresia is more prevalent

in Chinese individuals.12 13 14 15 16 The aim of this study was

to investigate the outcomes of fetuses with NVFGB

in a cohort of Chinese women; the findings may

provide guidance for the management of NVFGB.

Methods

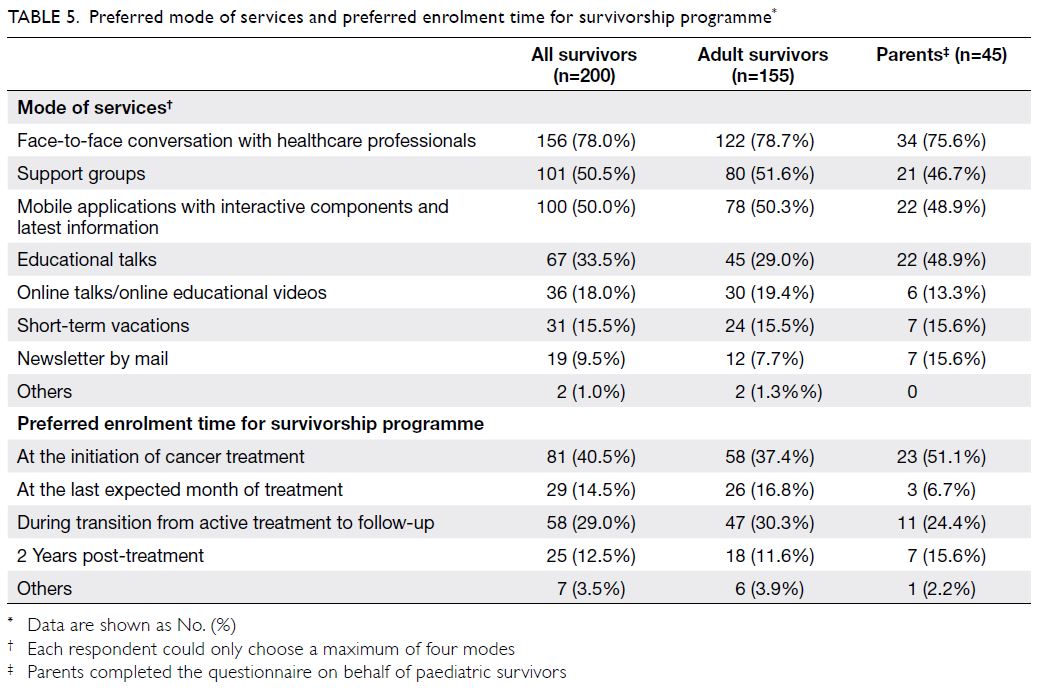

This retrospective review included cases of NVFGB

among Chinese pregnant women at five public fetal

medicine clinics in Hong Kong from 2012 to 2019.

In these clinics, fetal morphology scans were limited

to high-risk cases and fetal gallbladder assessment

was not routinely performed, in accordance

with guidelines from the International Society of

Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.5 17 When

cases of NVFGB were detected incidentally or

referred from private clinics, the pregnant women

were provided counselling regarding possible

differential diagnoses and offered amniocentesis

for chromosomal analysis. In cases of serious

fetal abnormalities where parents decided for

legal termination of pregnancy before 24 weeks of

gestation, post-mortem examinations were arranged

with parental consent. After birth, babies with

NVFGB were referred to paediatricians for further

evaluation.

The following data were reviewed: demographic

information, gestational age at detection of NVFGB,

findings during the morphology scan and subsequent

scans, results of all amniotic fluid investigations

if amniocentesis had been performed, pregnancy

outcome, all neonatal imaging reports, operations

performed on the baby and intra-operative findings,

and autopsy findings in case of termination of

pregnancy. The cases were segregated into isolated

and non-isolated groups according to the absence or presence of additional sonographic findings. The

incidences of subsequent visualisation of gallbladder,

gallbladder agenesis, biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis,

and chromosomal abnormalities were compared

between the two groups.

The study protocol was approved by the Joint

Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories

East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee

on 3 March 2020 (CREC Ref. No.: 2020.060). This

manuscript was written in accordance with STROBE

reporting guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons between

the isolated and non-isolated groups. All statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS software

(Windows version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk [NY],

United States). P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant.

Results

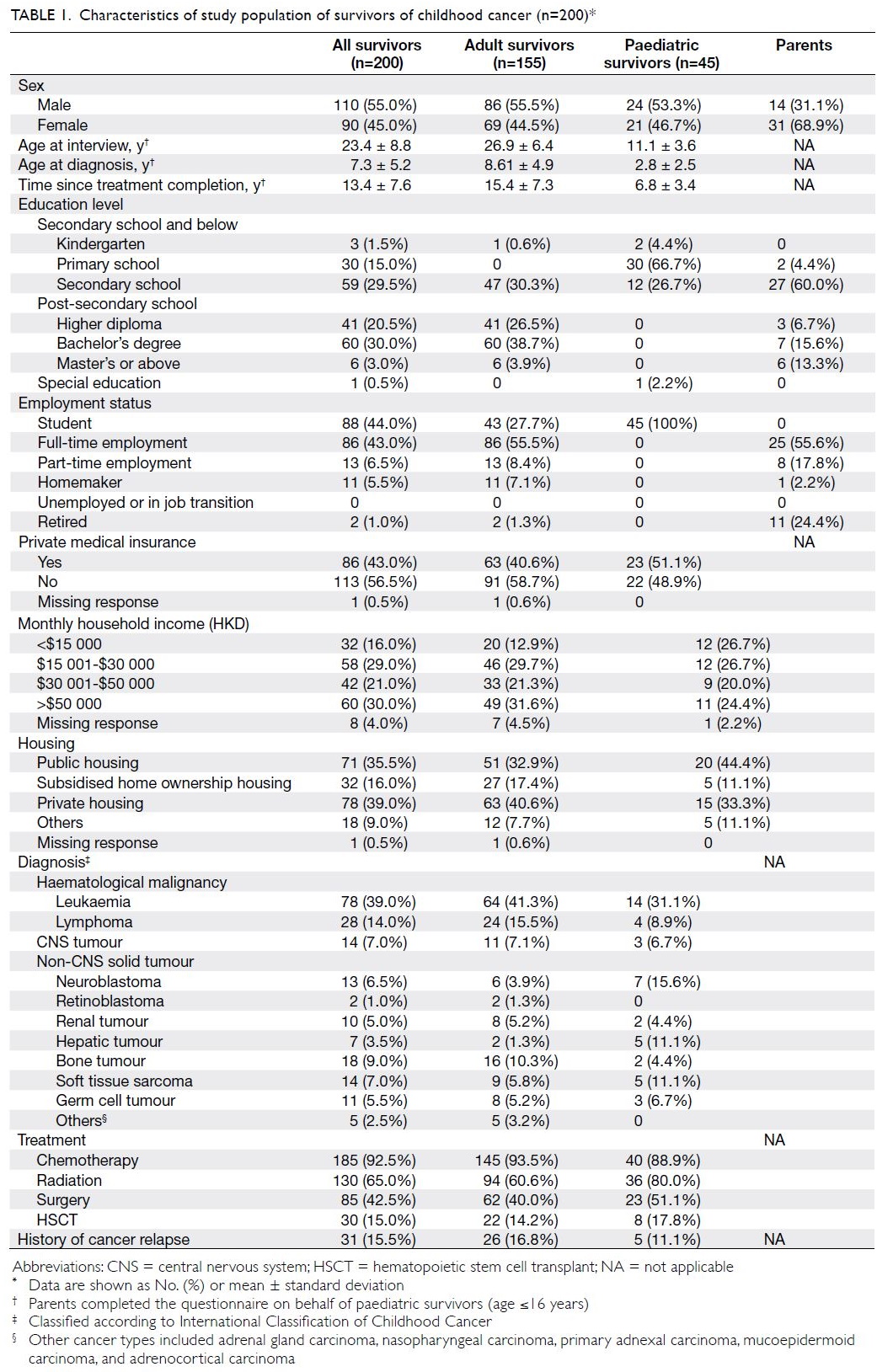

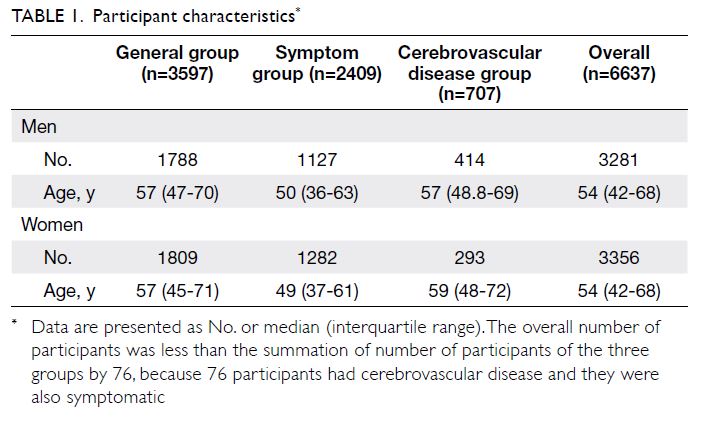

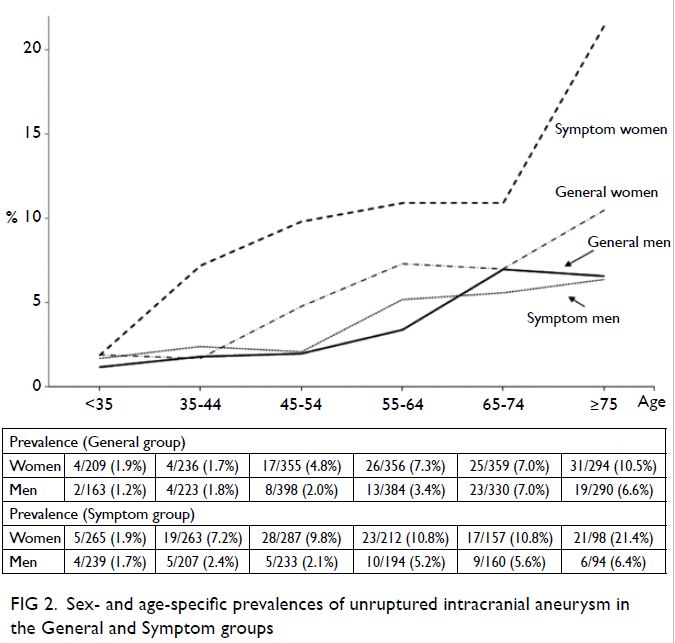

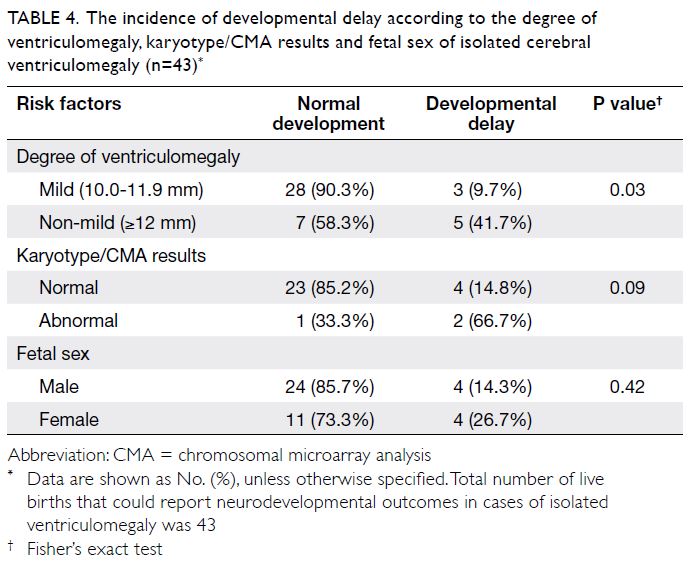

Among 19 cases of NVFGB detected at a median

gestational age of 21.3 weeks (interquartile range,

20.0-22.3 weeks), 10 (52.6%) were isolated and nine

(47.4%) were non-isolated. Eleven (58.0%) cases

had transient non-visualisation, four (21.0%) had

gallbladder agenesis, three (15.8%) had chromosomal

abnormalities (trisomy 18, trisomy 21, and 22q11.2

de novo microduplication), and one (5.2%) had

biliary atresia. There were no cases with features

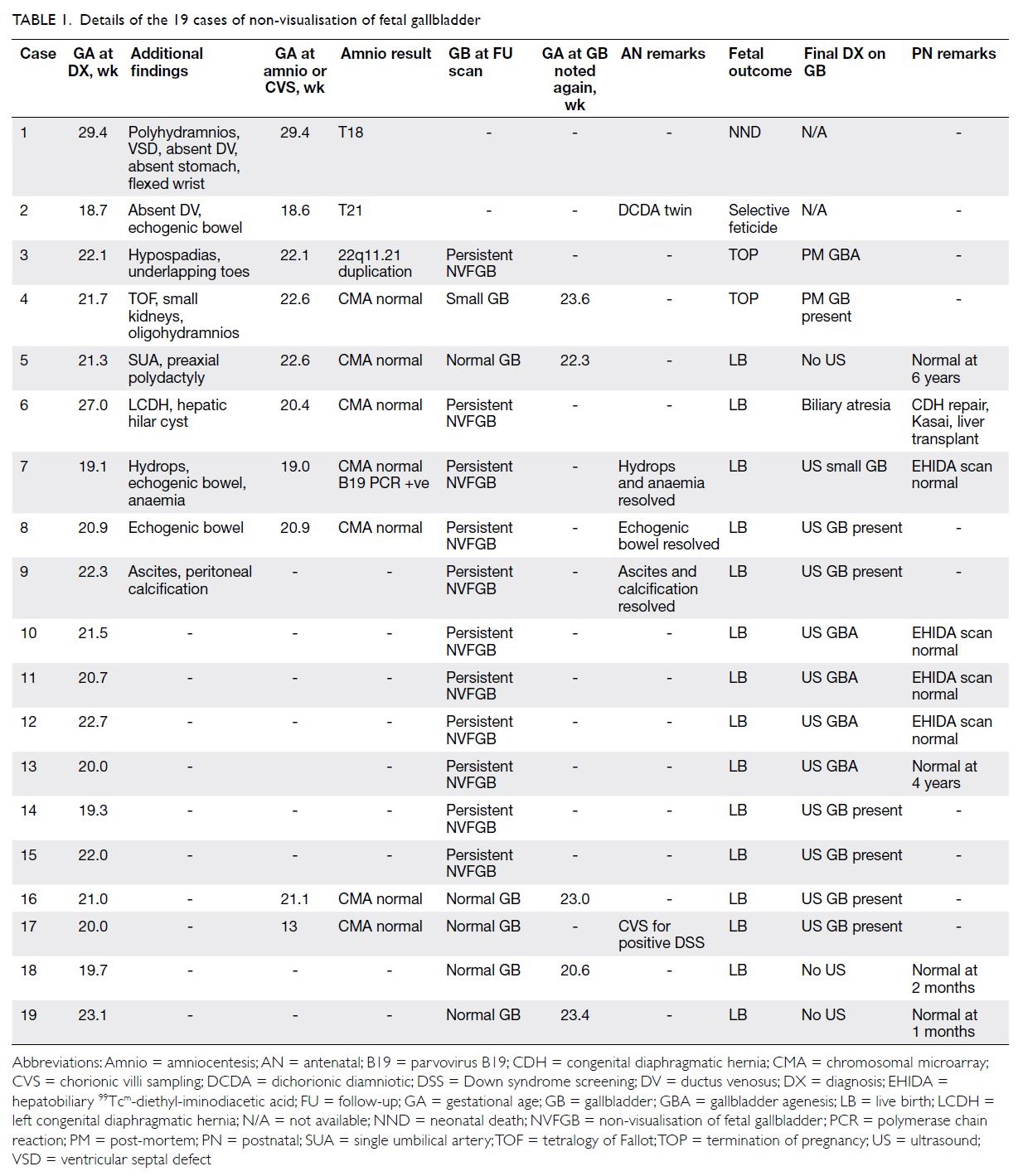

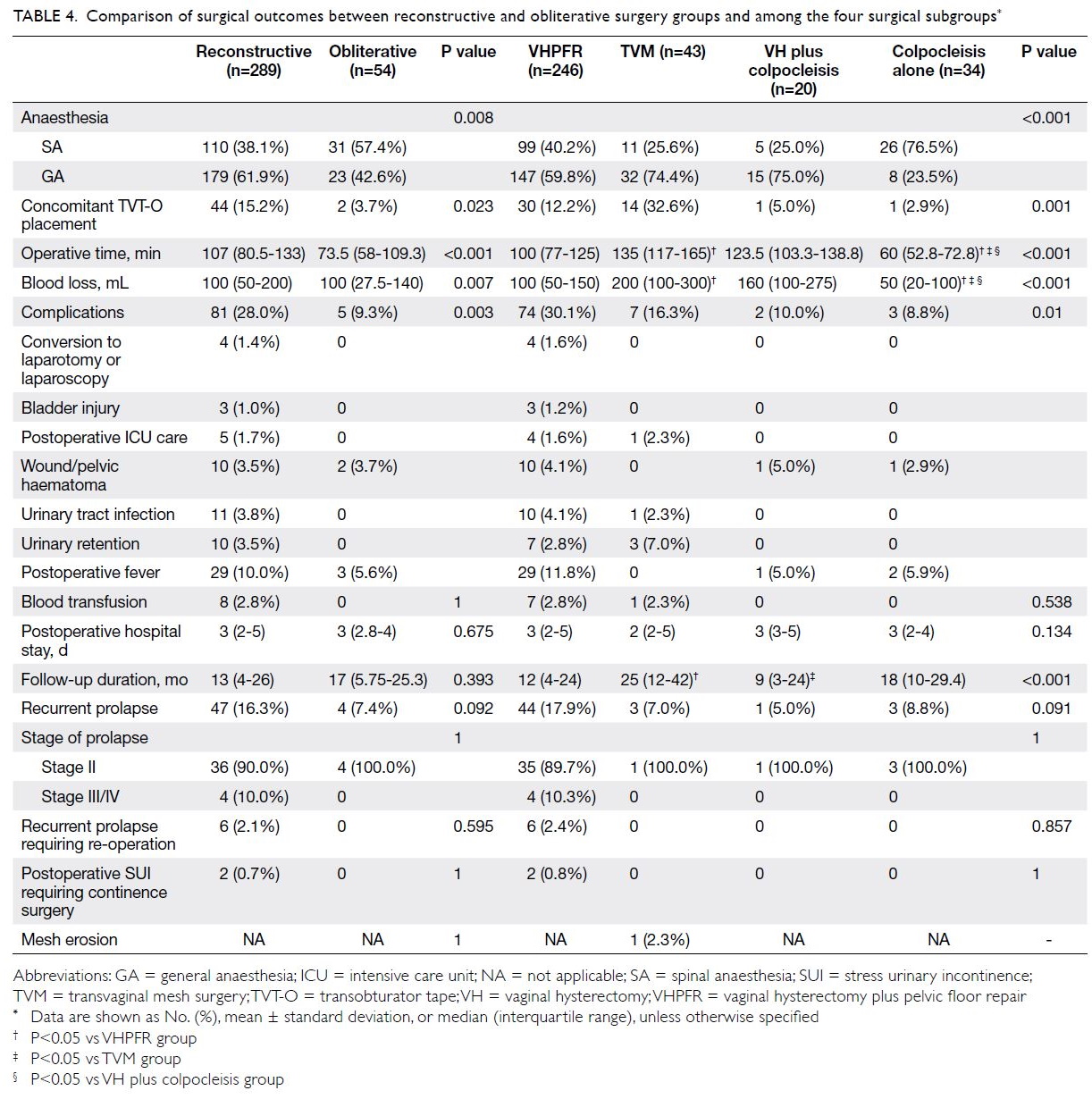

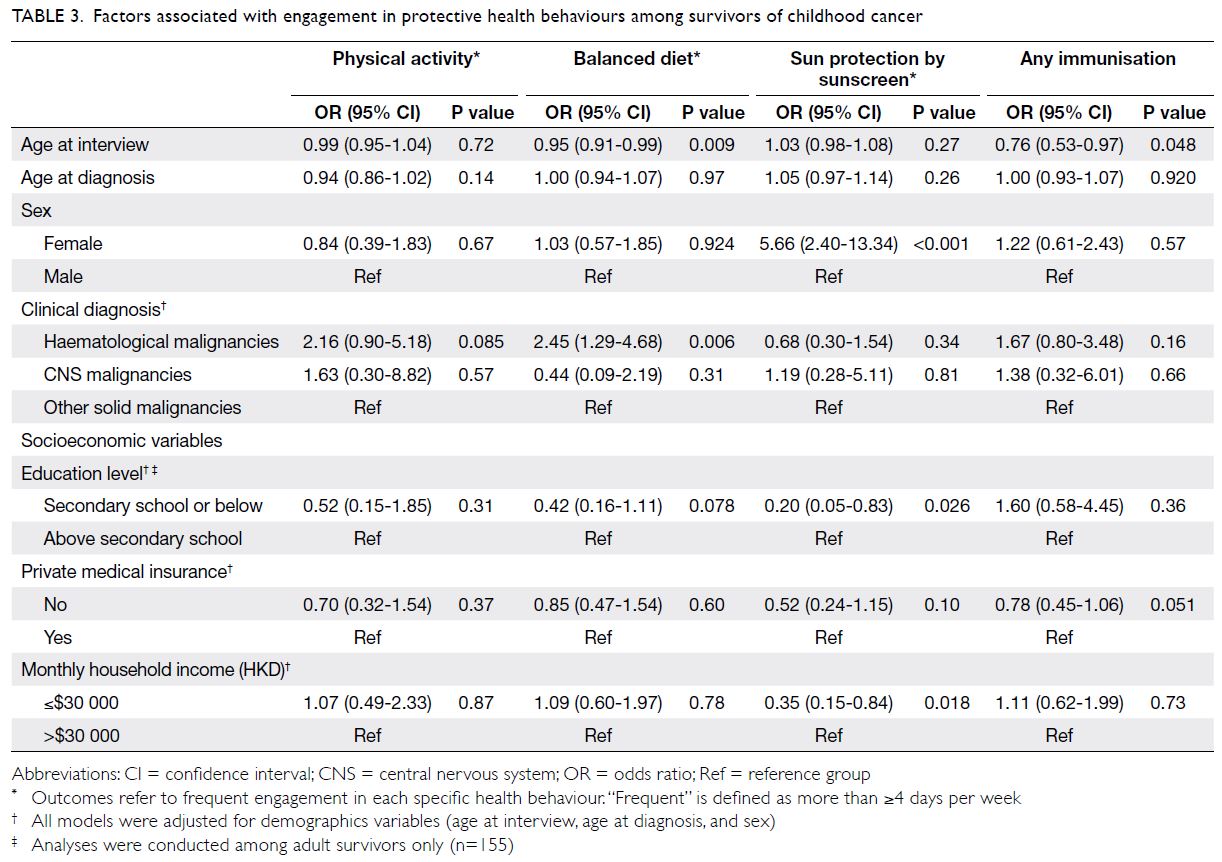

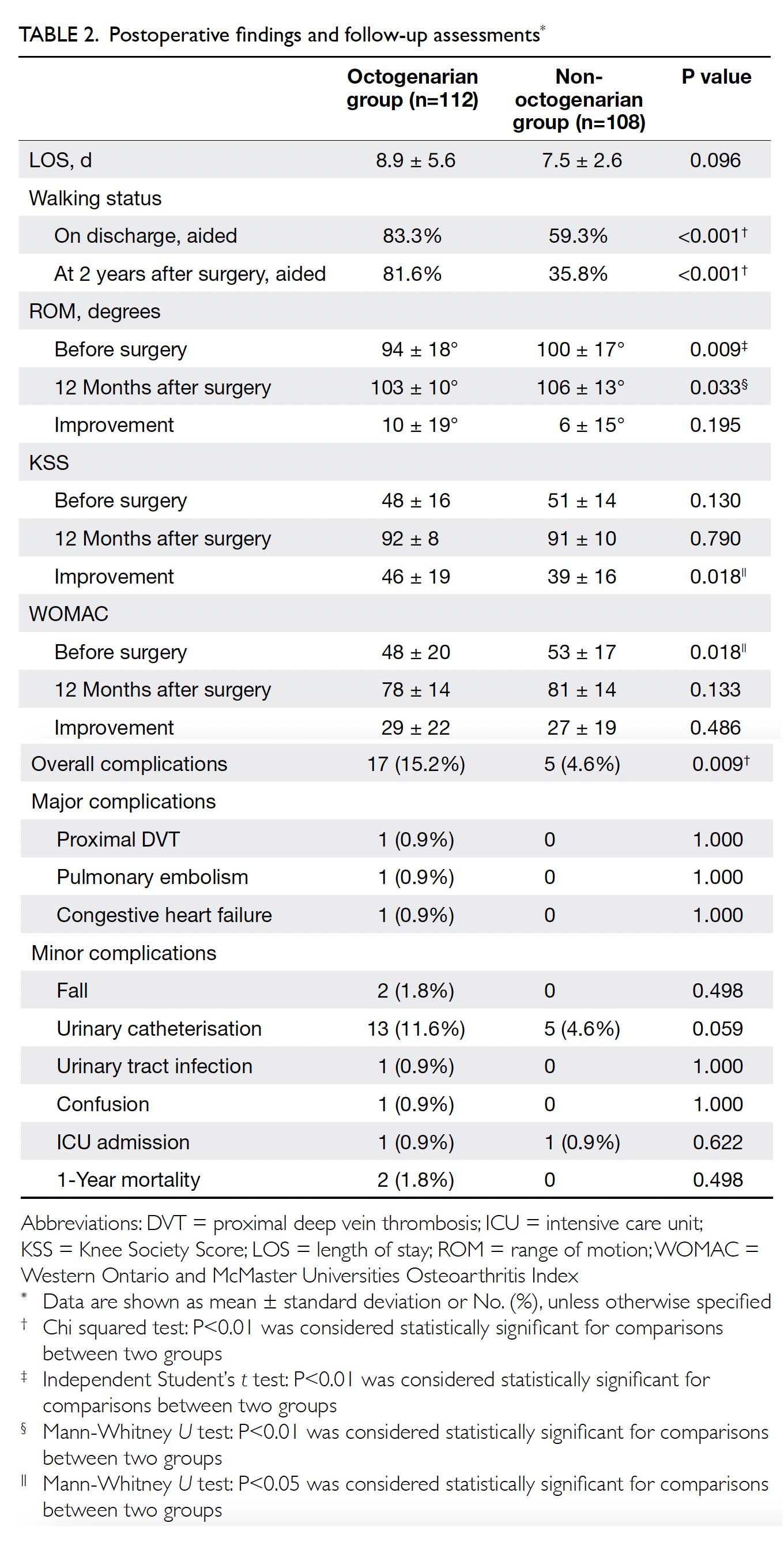

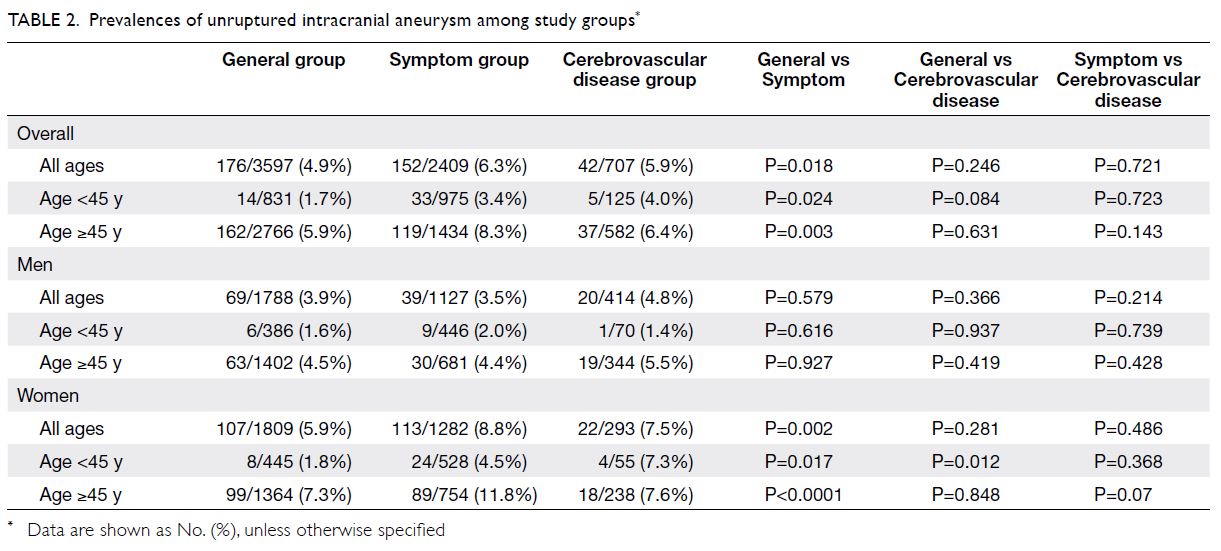

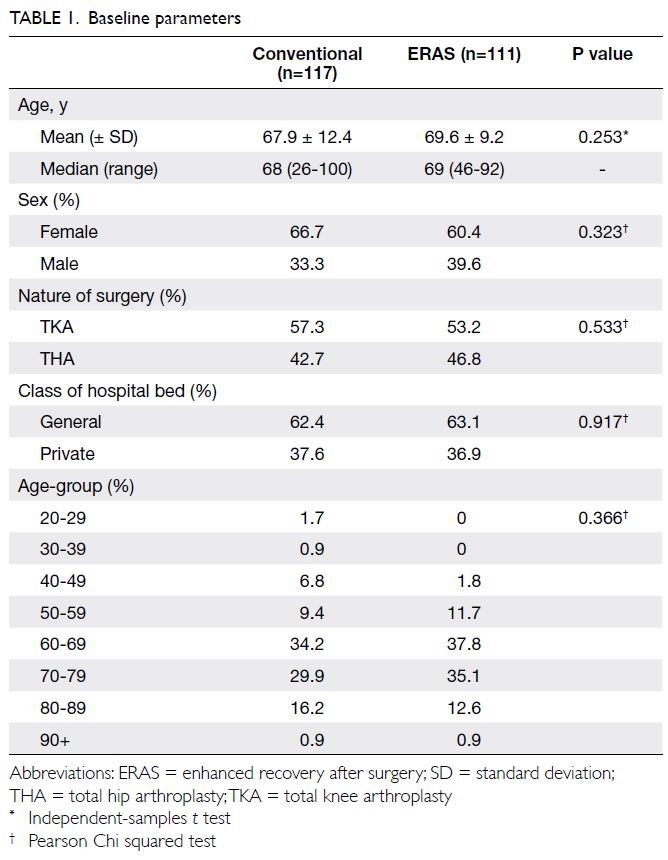

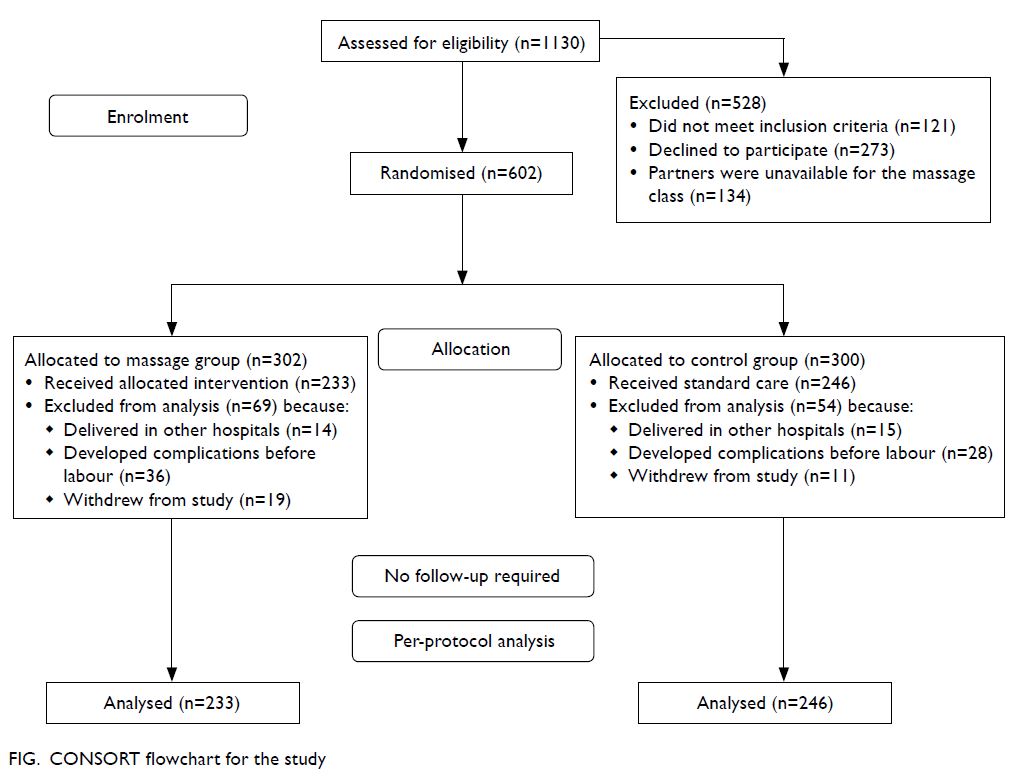

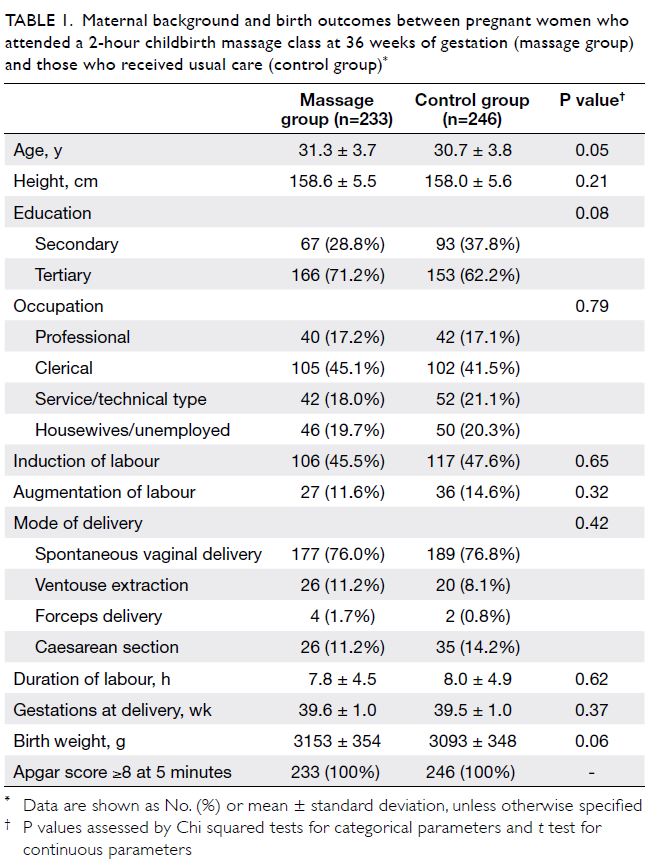

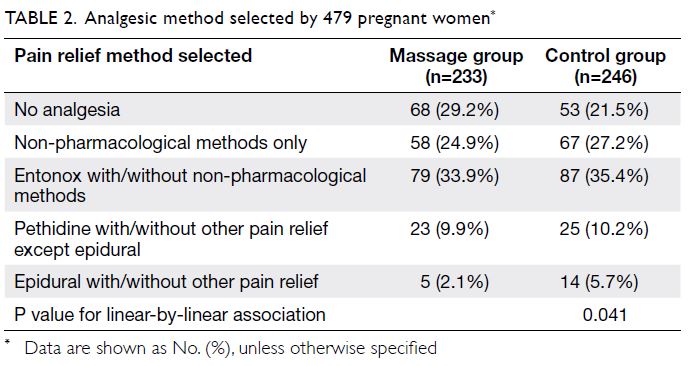

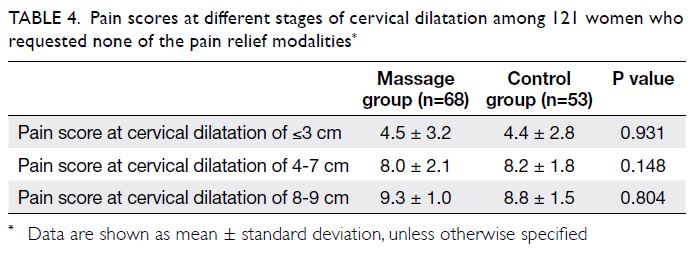

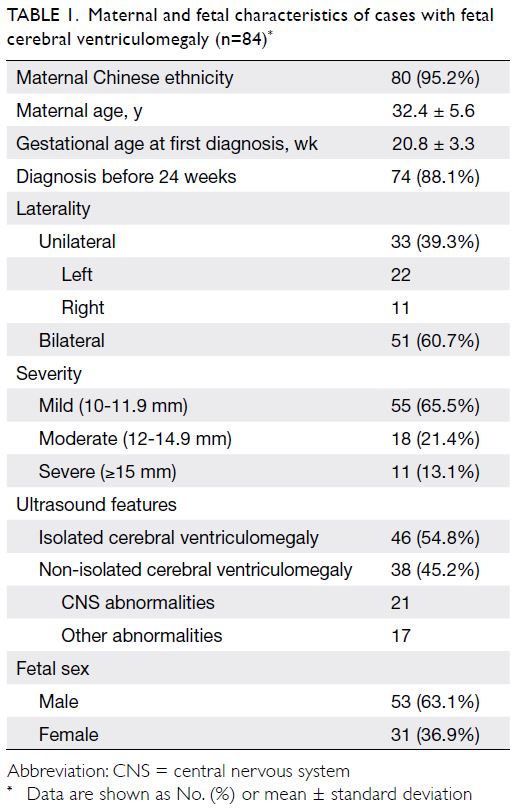

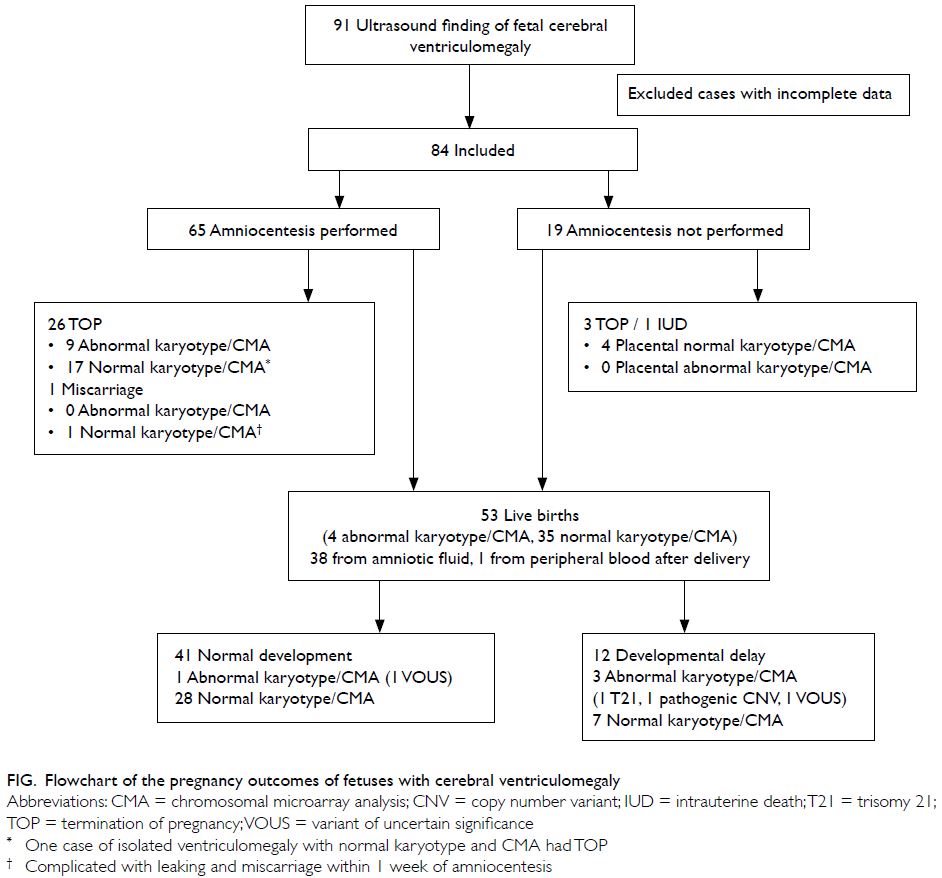

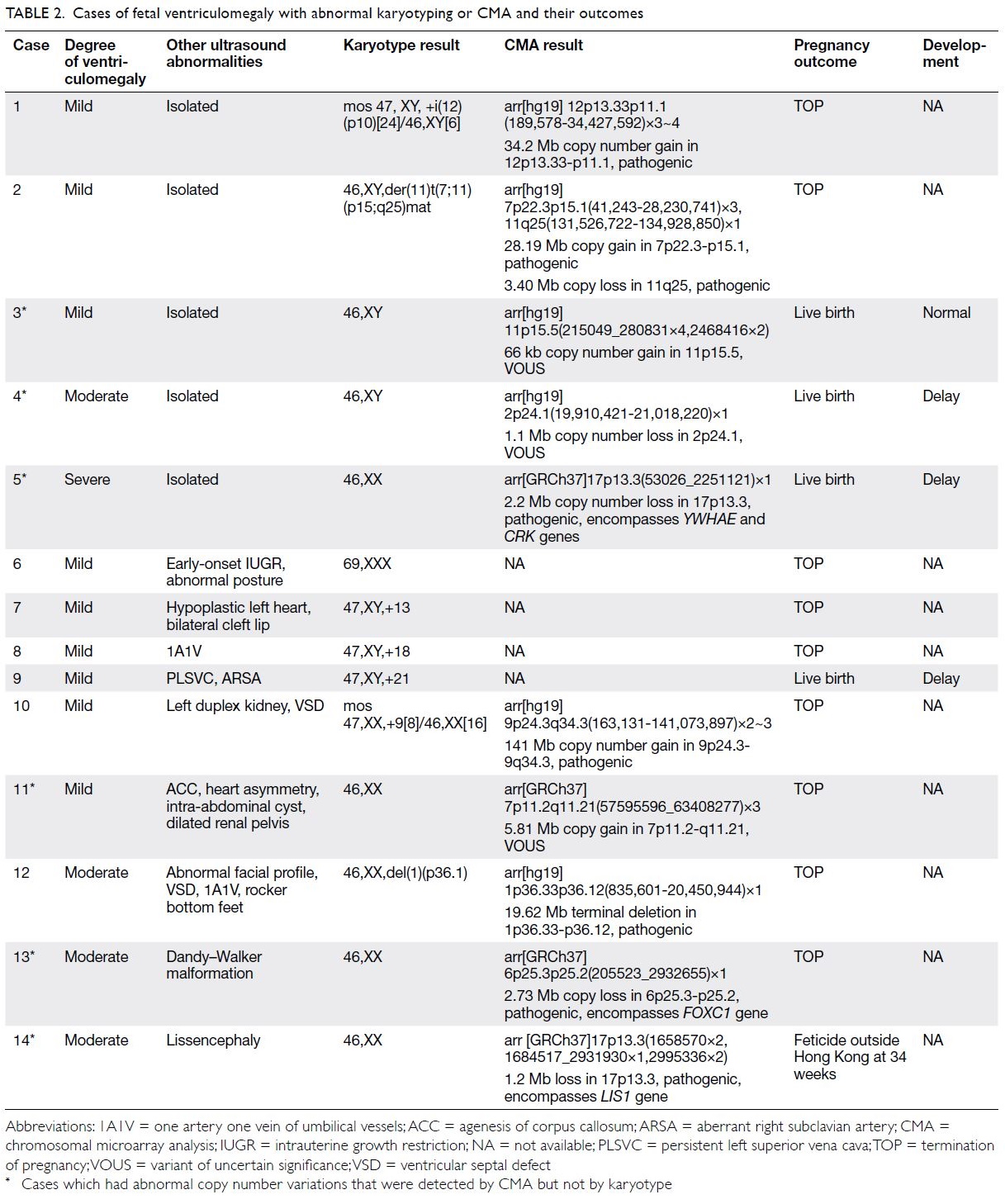

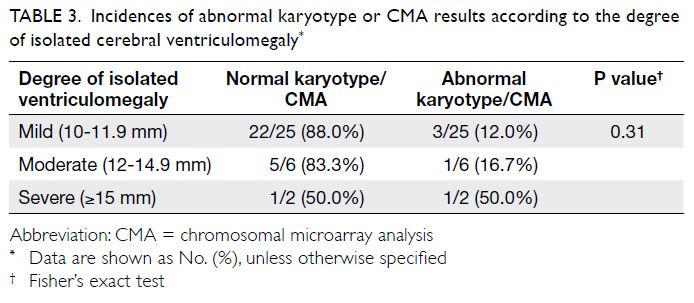

suggestive of cystic fibrosis (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2. Comparison of characteristics between isolated and non-isolated cases of non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder

Non-isolated non-visualisation of fetal

gallbladder

Amniocentesis was performed in eight of the

nine non-isolated cases; three chromosomal

abnormalities (33.3%) were found, including trisomy

18 (case 1), trisomy 21 (case 2), and 22q11.2 de

novo microduplication (case 3). Case 1 ended in

neonatal death and the parents declined post-mortem

investigation. Case 2 was a dichorionic twin

pregnancy; selective feticide was performed on the

fetus with trisomy 21, but post-mortem investigation

could not be performed because of the long interval

between selective feticide and delivery of the normal

co-twin. Termination of pregnancy was performed

in case 3 and gallbladder agenesis was confirmed

at autopsy. Termination of pregnancy was also

performed in case 4 because of multiple structural

abnormalities; chromosomal microarray (CMA)

findings were normal and post-mortem investigation

revealed normal gallbladder. Live birth occurred in

the remaining five cases; in one case, the gallbladder

was observed during a subsequent antenatal scan

and the postnatal outcome was normal, while

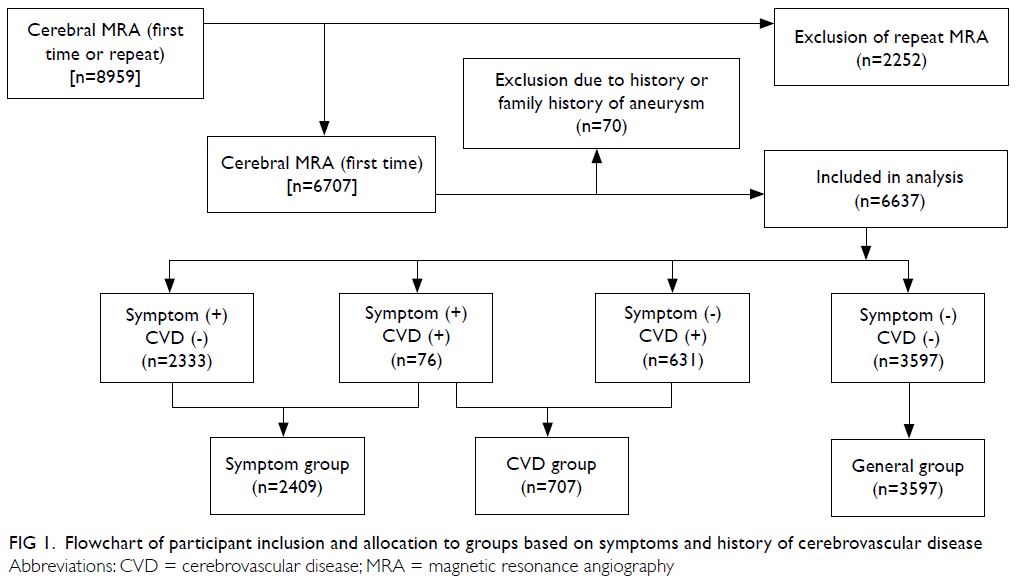

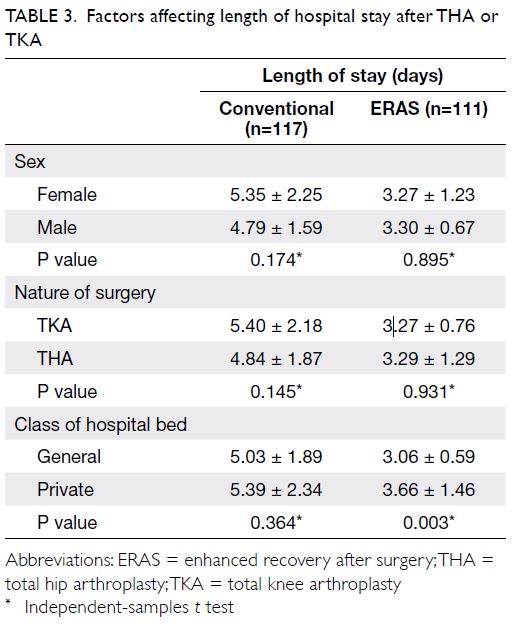

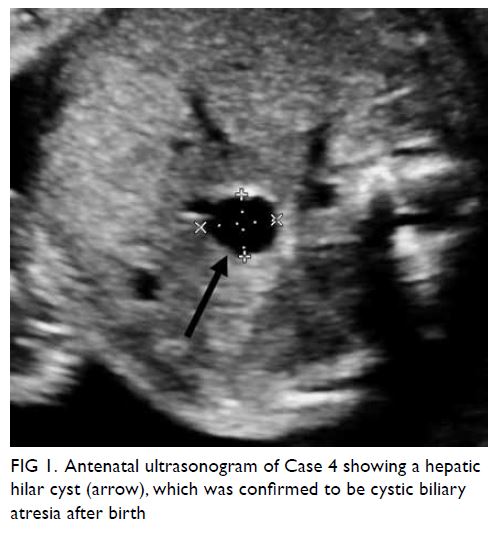

NVFGB persisted in the other four cases. Among

the four cases with persistent NVFGB, one (11.1%) had biliary atresia that required liver transplantation

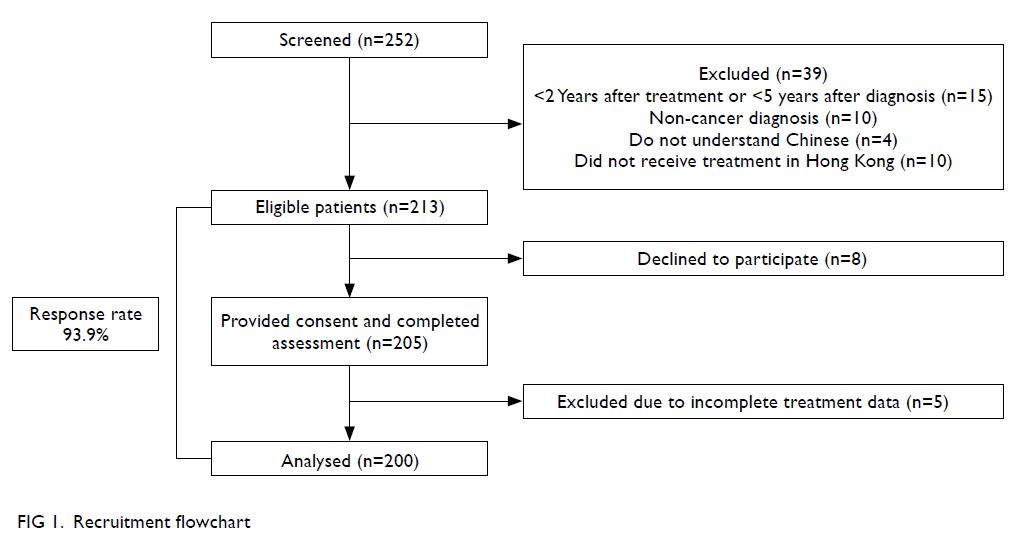

(case 6); antenatal scans had shown a hepatic hilar

cyst (Fig 1), which was highly suggestive of cystic

biliary atresia.18 Postnatal examination showed a

normal gallbladder in the other three cases. None of

the five live births had features suggestive of cystic

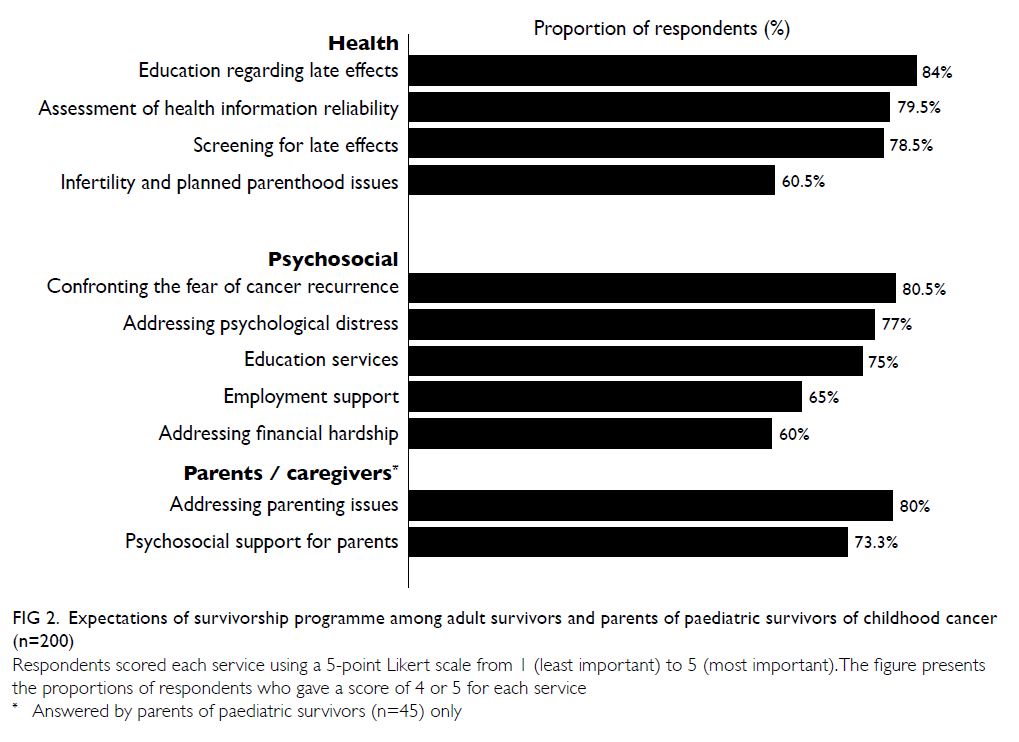

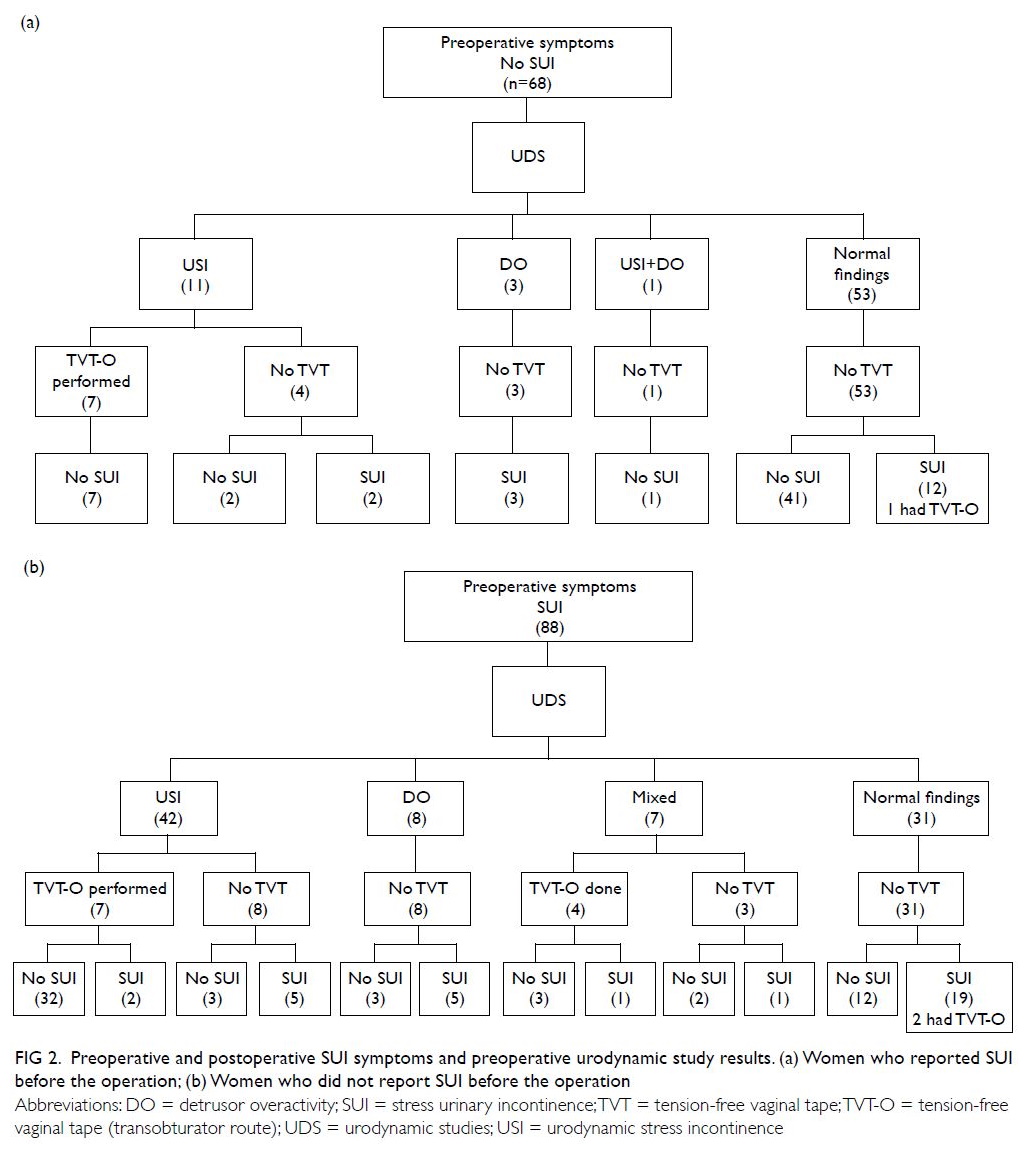

fibrosis (Table 1 and Fig 2).

Figure 1. Antenatal ultrasonogram of Case 4 showing a hepatic hilar cyst (arrow), which was confirmed to be cystic biliary atresia after birth

Figure 2. Diagram of the underlying diagnoses in 19 cases of non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder (NVFGB) in our Chinese cohort

Isolated non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder

Among the 10 cases of isolated NVFGB,

amniocentesis was performed in one, while chorionic

villi sampling was performed in the first trimester

because of positive Down syndrome screening

result in another; CMA findings were normal in

both cases. In four cases, gallbladders were observed

during subsequent antenatal scans at a mean follow-up

interval of 1.0 week (range, 0.3-2.0); NVFGB

persisted in the other six cases. Among the six cases

with persistent NVFGB, gallbladder agenesis was

confirmed in four (66.7%) and gallbladders were

observed after birth in two (33.3%). None of the 10

cases had features suggestive of cystic fibrosis after

birth (Table 1 and Fig 2).

Comparison between the isolated and non-isolated

groups

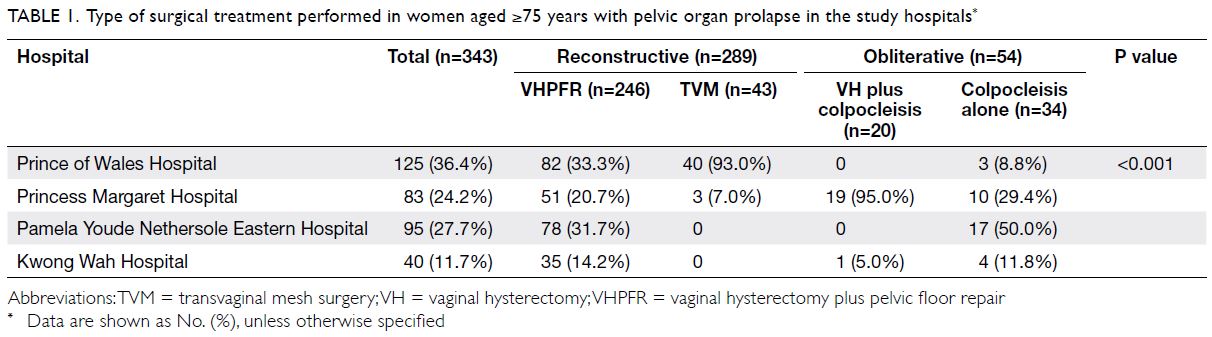

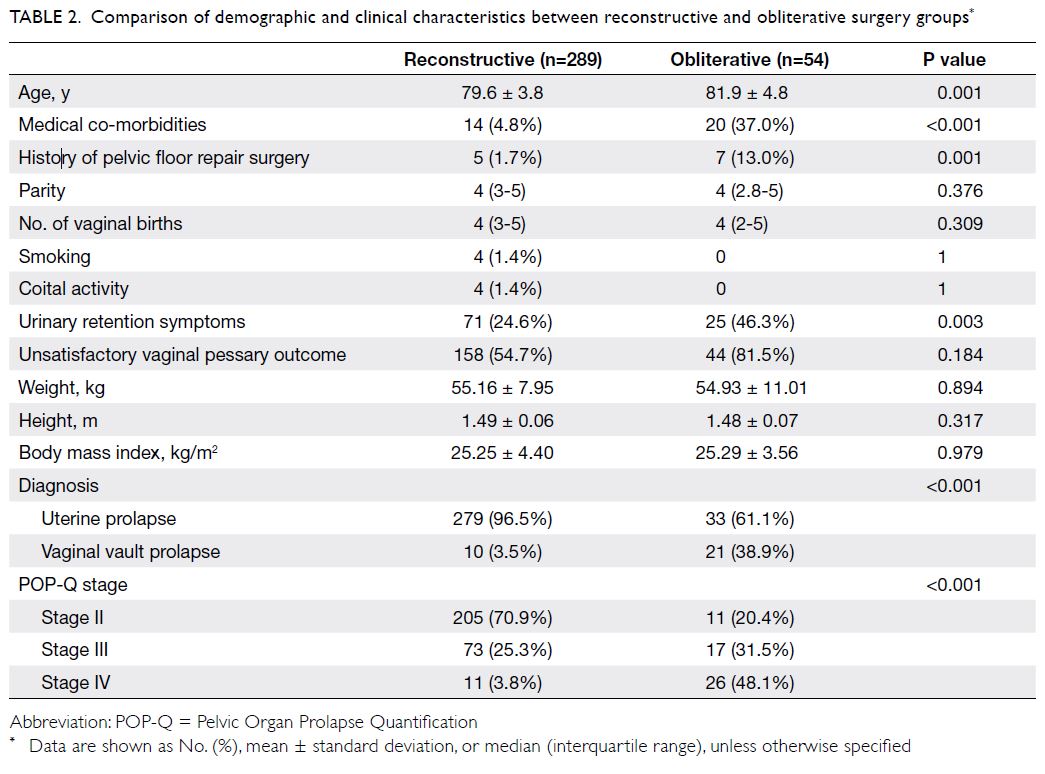

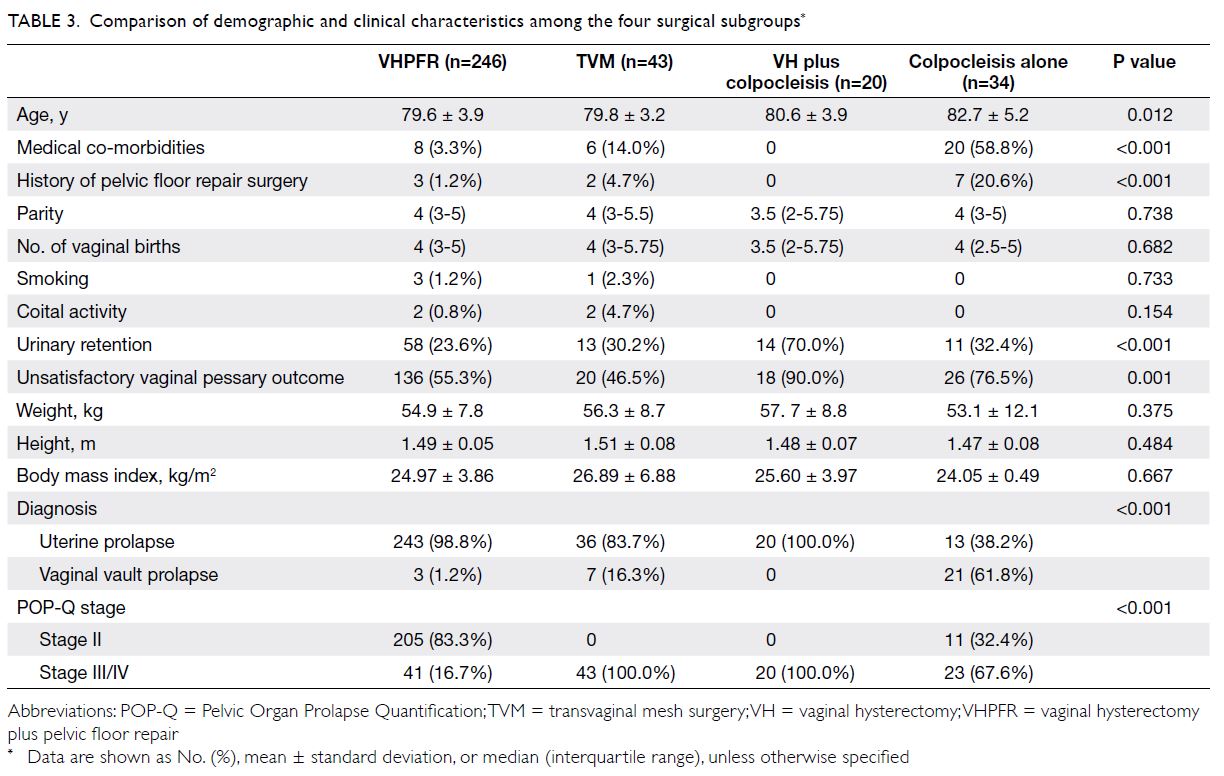

The characteristics of isolated and non-isolated

groups are compared in Table 2. The incidence of

serious abnormalities (chromosomal abnormalities,

biliary atresia) was significantly higher in the non-isolated

group than in the isolated group (44.4% vs

0%; P=0.029). Notably, all serious conditions in the

cohort (all three cases of chromosomal abnormalities

and the only case of biliary atresia) were observed in

the non-isolated group, while all benign conditions

(all four cases of isolated gallbladder agenesis) were

observed in the isolated group. The incidences of

transient non-visualisation did not significantly

differ between the isolated and non-isolated groups

(60.0% vs 55.6%; P=1.000).

Discussion

Isolated non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder

In our cohort, cases of isolated NVFGB had a good

overall prognosis, with a 60% probability that the

gallbladder would be observed in a subsequent

scan and a 40% probability of gallbladder agenesis.

This incidence of transient non-visualisation (60%)

is consistent with findings by Yayla and Bayik2

(75%) and Di Pasquo et al11 (69.4%). In our cases

of transient NVFGB, the gallbladder was observed

during a subsequent antenatal scan in 40%, and

during the postnatal period in the remaining 20%.

The mean interval between NVFGB and subsequent

antenatal detection of the gallbladder was 1 week.

Therefore, a second sonographic examination

within 1 week after NVFGB would help to alleviate parental anxiety and avoid the need for further

investigations in nearly half of such cases. Even in

cases with persistent isolated NVFGB, the prognosis

remains good, because the gallbladder is likely to

be observed after birth in one-third of cases; while gallbladder agenesis is likely in the remaining cases.

Our findings are similar to the results of a recent

systematic review of seven studies in Western

populations, including 217 cases of isolated NVFGB;

most cases had transient non-visualisation (69.4%) and gallbladder agenesis (24.7%), but some cases

had serious conditions (biliary atresia [3.5%], cystic

fibrosis [2.4%], and chromosomal abnormalities

[1.4%]).11 Therefore, further investigations to rule

out such serious abnormalities remain important in

cases of isolated NVFGB.

Non-isolated non-visualisation of fetal

gallbladder

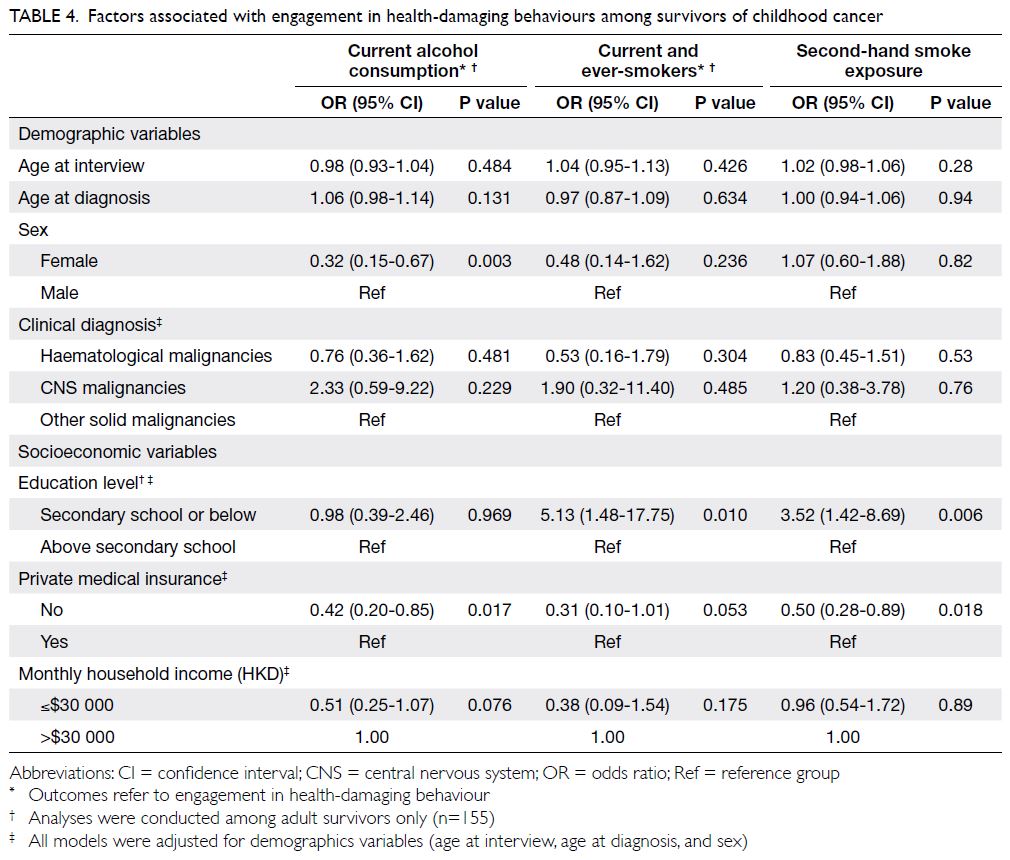

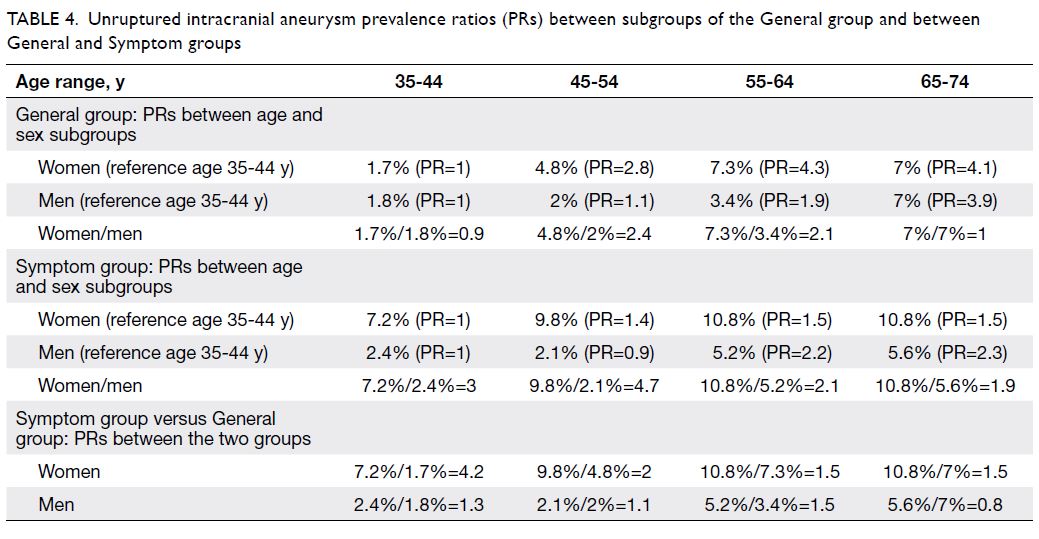

In the aforementioned review, the incidences of

biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, and chromosomal

abnormalities were much higher when NVFGB

occurred in combination with other ultrasound

abnormalities (18.2%, 23.1%, and 20.4%,

respectively).11 Copy number variants were

observed in one of three cases with chromosomal

abnormalities in our study and two of 11 such cases

in the study by Di Pasquo et al11; these findings support the recommendation for the use of CMA,

rather than karyotyping.19 20 21 However, our results

differ from the findings reported by Di Pasquo et al11

in that none of our cases had cystic fibrosis, which is

unsurprising because cystic fibrosis is rare in Chinese

individuals; moreover, our incidence of biliary atresia

(11.1%) was much lower than expected, considering

that biliary atresia is reportedly threefold more

common in Chinese individuals than in Caucasian

individuals.12 13 14 15 16

Non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder and

biliary atresia

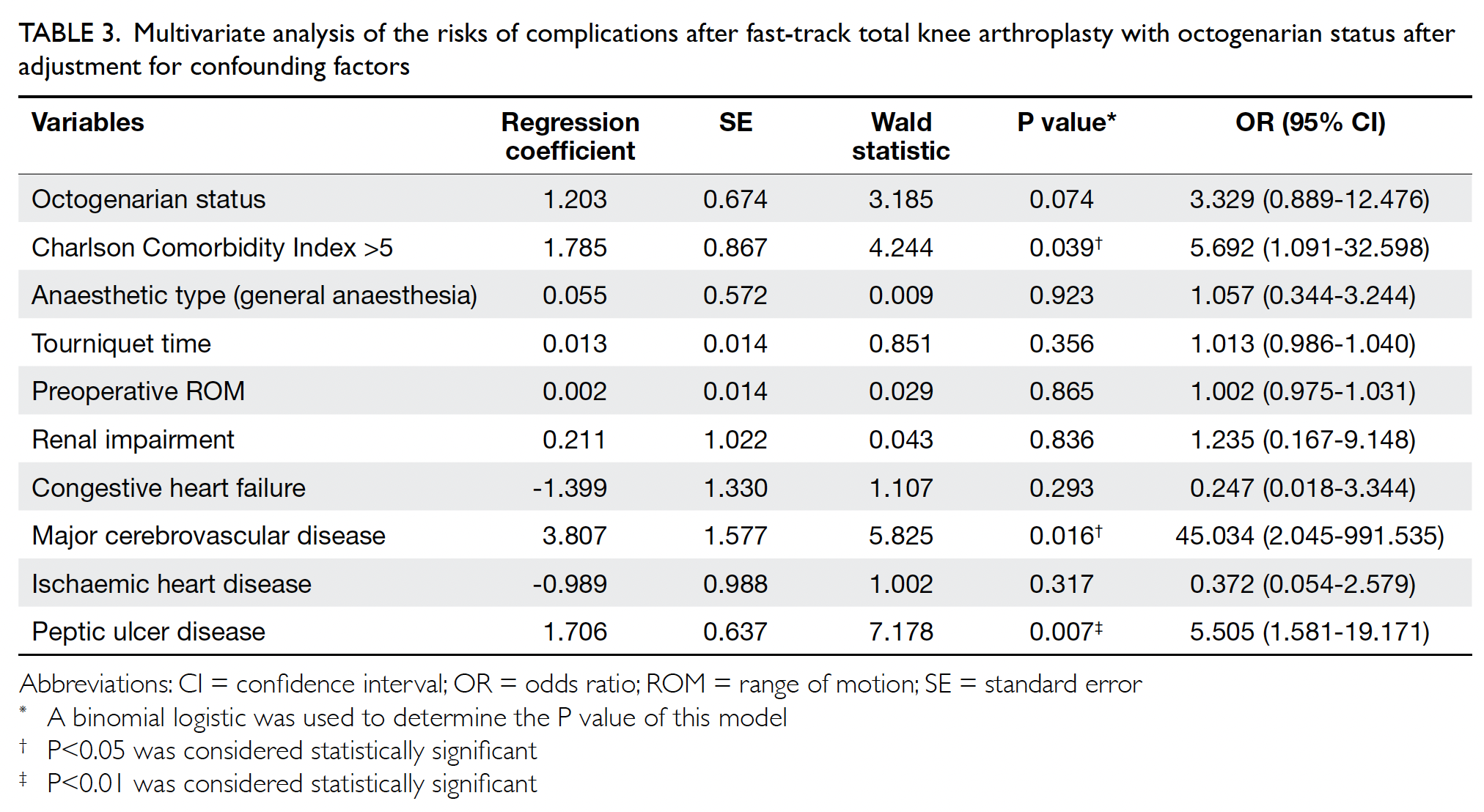

Based on the data described above, in cases of non-isolated

NVFGB or persistent isolated NVFGB,

amniocentesis may help to rule out chromosomal

abnormalities; this approach is generally simple with

current CMA technology.19 20 However, the antenatal

diagnosis of biliary atresia is challenging because

fetal bile duct patency cannot be determined by

sonographic examination; NVFGB may be the only

suggestive sign of biliary atresia. When NVFGB is

associated with a hepatic hilar cyst or heterotaxy,

a diagnosis of biliary atresia is likely.18 However,

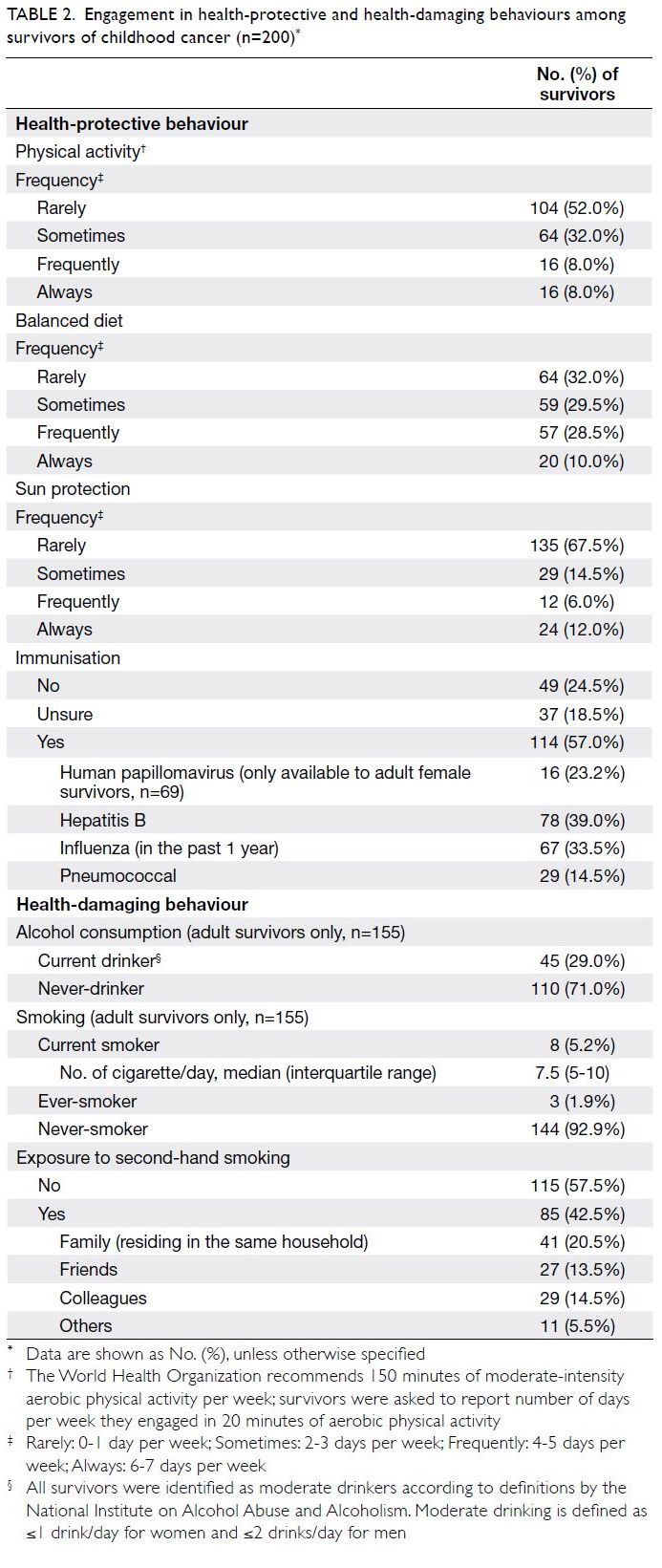

it is difficult to differentiate biliary atresia from

gallbladder agenesis in cases of isolated NVFGB.

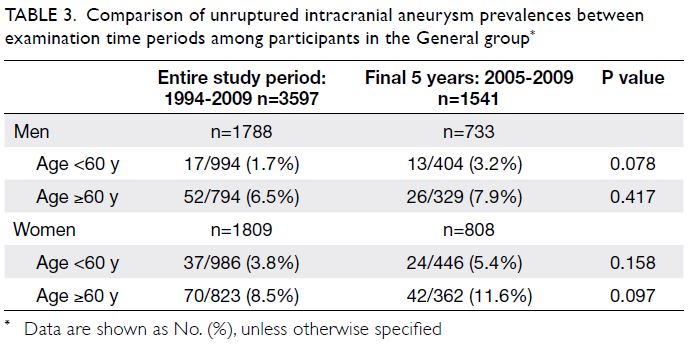

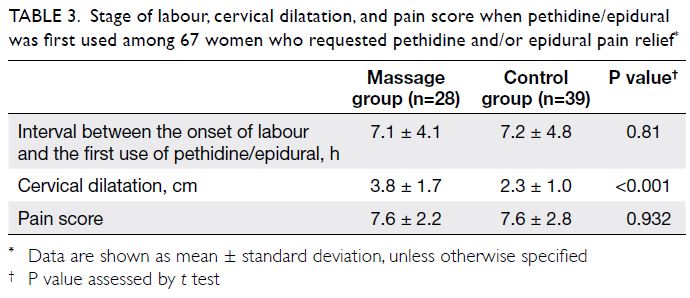

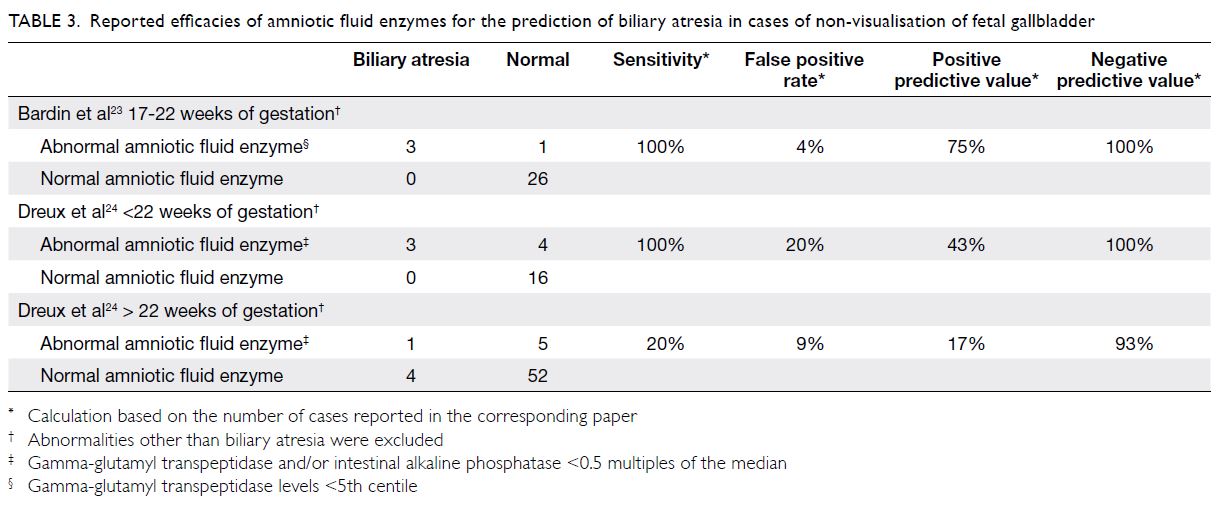

Thus, a low amniotic fluid gamma-glutamyl

transpeptidase (AFGGT) level has been proposed as

an indicator of biliary atresia.22 23 24 Gamma-glutamyl

transpeptidase (GGT) is initially derived from the

fetal biliary tract, passed into the gastrointestinal

tract, and finally excreted into the amniotic fluid.

The AFGGT level decreases with increasing

gestational age because progressive maturation

of the anal sphincter impairs the passage of GGT

from the gastrointestinal tract into the amniotic

fluid.22 25 26 The anal sphincter muscles become fully

mature by 20 weeks of gestation, and the AFGGT

level becomes very low after 22 weeks of gestation.

Therefore, it may be difficult to distinguish between

a low level related to biliary atresia and a low level related to normal development after 22 weeks of

gestation.25 26 Using an AFGGT level below the 5th

centile, Bardin et al23 reported 100% sensitivity in

the detection of biliary atresia, with a false positive

rate of 4%, between 17 and 22 weeks of gestation

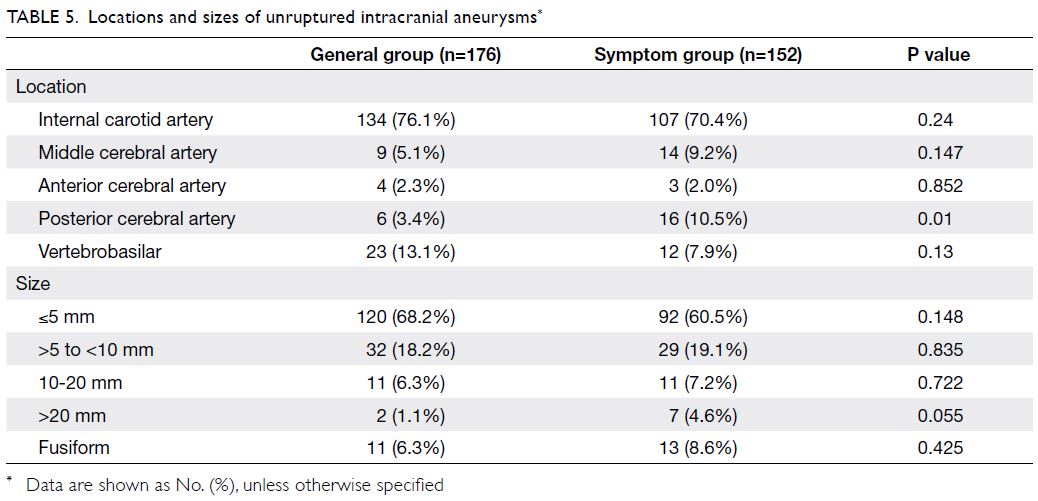

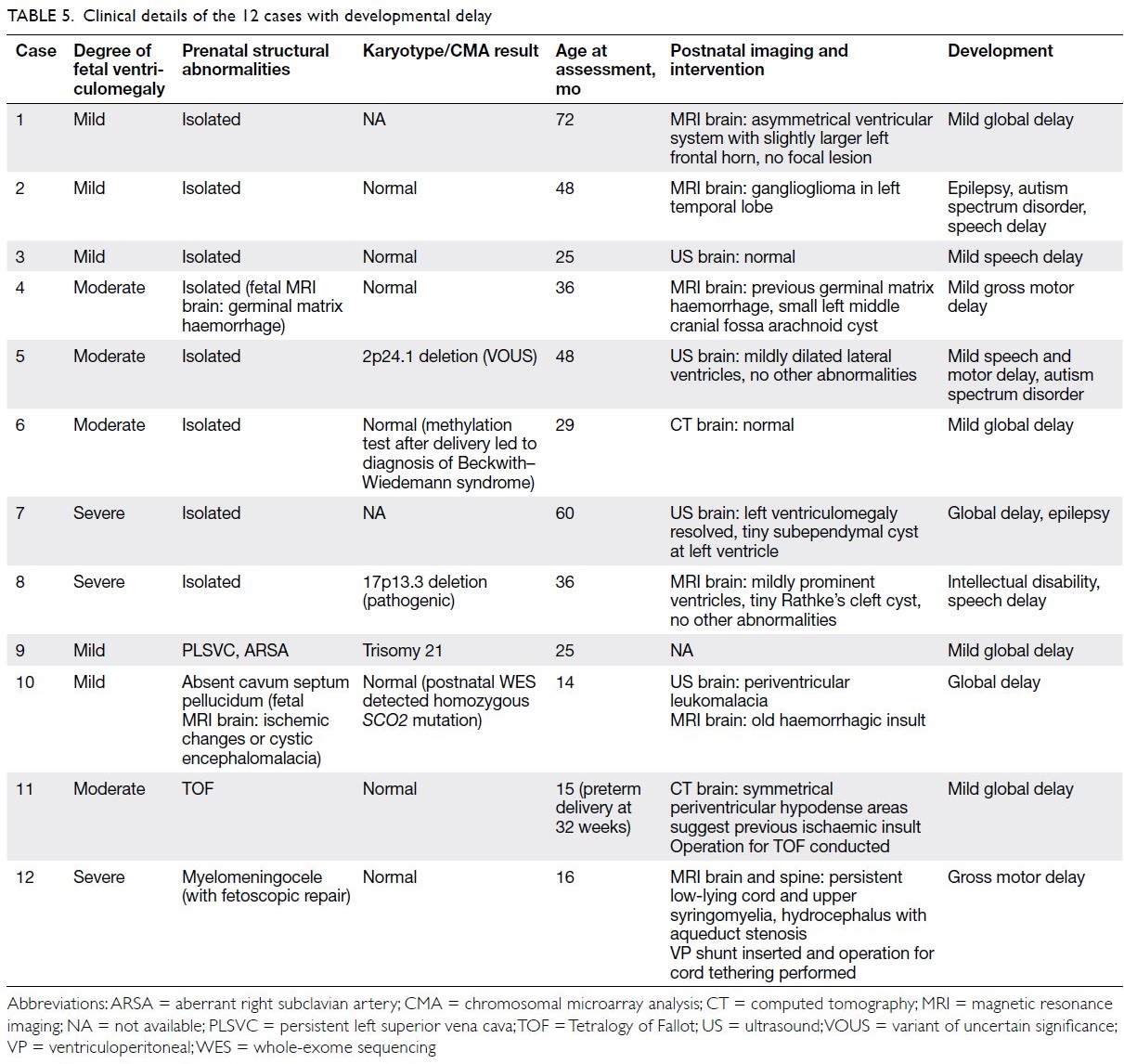

(Table 3). Using AFGGT level and/or intestinal

alkaline phosphatase <0.5 multiples of the median,

Dreux et al24 also reported 100% sensitivity before

22 weeks of gestation; however, their false positive rate was 20%. Notably, when the test was performed

after 22 weeks of gestation, the sensitivity decreased

to 20%. Therefore, gestational age at amniocentesis

is a critical consideration during the assessment

of biliary atresia; if NVFGB is first detected near

22 weeks of gestation, amniocentesis should be

performed immediately, rather than waiting for

sonographic examination to be repeated. Another

limitation of using the AFGGT level to identify biliary atresia is that it has a moderately low positive

predictive value: 43% to 75% before 22 weeks of

gestation, and 17% thereafter.23 24 Accordingly, a

positive AFGGT test result is not diagnostic of

biliary atresia, particularly in cases of isolated

NVFGB where the incidence of biliary atresia is

presumably low. Conversely, the negative predictive

value of AFGGT is near 100%; a negative test result

is very reassuring, which can help to alleviate

parental anxiety and avoid unwarranted termination

of pregnancy.23 24 When NVFGB is detected after

22 weeks of gestation, the fetal blood GGT level

may be useful for identification of biliary atresia.27 28

However, cordocentesis may be unwarranted, as

the procedure-related risk outweighs the possible

diagnostic benefit, particularly in cases of isolated

NVFGB where the risk of biliary atresia is presumably

low.

Table 3. Reported efficacies of amniotic fluid enzymes for the prediction of biliary atresia in cases of non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder

Non-visualisation of fetal gallbladder and

cystic fibrosis

In Caucasian populations, the incidence of cystic

fibrosis is 1:2500-3500 live births and the carrier

rate is 1:50; in contrast, this hereditary disease

is extremely rare among East Asian individuals

(1:350000 people in Japan and 1:300000 live births

in Hong Kong).15 16 29 Unsurprisingly, we did not

observe cystic fibrosis in either group of NVFGB

cases. Therefore, in the absence of significant family

history, consanguinity, or concurrent ultrasound

features suggestive of cystic fibrosis (eg, echogenic

or dilated bowel), amniocentesis for genetic testing

for cystic fibrosis is not recommended in cases of

NVFGB in Hong Kong. Assessment of the parental

CFTR gene mutation status may be a useful

alternative.

Management protocol for non-visualisation

of fetal gallbladder

Based on our findings and the results of previous

studies, we propose the following approach for the

management of NVFGB. When NVFGB is detected,

a detailed morphology scan should be performed to

identify associated abnormalities, such as hepatic

hilar cyst and heterotaxy (indicative of biliary

atresia) or echogenic and dilated bowel (suggestive

of cystic fibrosis). A sonographic examination

of the gallbladder should be repeated within

1 week. Considering the potential for chromosomal

abnormalities (even in cases of isolated NVFGB),

amniocentesis is recommended for CMA analysis

in cases of persistent NVFGB. The AFGGT assay

can also be performed before 22 weeks of gestation;

counselling prior to the test should involve an

explanation of the moderately low positive predictive

value for identification of biliary atresia. Beyond

22 weeks of gestation, the AFGGT level is not useful

for identifying biliary atresia, but cordocentesis for GGT level may be useful. However, cordocentesis is

generally not recommended because the procedure-related

risk outweighs the possible diagnostic

benefit, particularly in cases of isolated NVFGB

where the risk of biliary atresia is presumably low.

Further testing for cystic fibrosis may be unnecessary

in Chinese fetuses unless the NVFGB is associated

with other ultrasound features suggestive of cystic

fibrosis, significant family history, or consanguinity.

Further research is needed concerning AFGGT

reference values and the ability of the AFGGT level

to identify biliary atresia in Chinese fetuses with

NVFGB.

Limitations and strength

Similar to other reports regarding NVFGB, our study

was limited by its retrospective design and small

cohort size. Because fetal gallbladder examination

has not been a routine practice in Hong Kong, we

cannot calculate the prevalence of NVFGB. To our

knowledge, this is the first report of NVFGB in

a Chinese cohort. Moreover, our results differed

from findings in Caucasian populations in that

we did not observe cystic fibrosis in our cohort;

such information may be useful during antenatal

counselling in cases of NVFGB.

Conclusion

The prognosis of isolated NVFGB is generally good

because the non-visualisation is either transient or

related to gallbladder agenesis. While investigations

of chromosomal abnormalities and biliary atresia

are reasonable in cases of NVFGB, testing for cystic

fibrosis may be unnecessary in Chinese fetuses unless

the NVFGB is associated with consistent ultrasound

features, significant family history, or consanguinity.

Author contributions

Concept or design: YH Ting, TY Leung.

Acquisition of data: YH Ting, PL So, KW Cheung, TK Lo, TWL Ma.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YH Ting.

Drafting of the manuscript: YH Ting, TY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YH Ting, PL So, KW Cheung, TK Lo, TWL Ma.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YH Ting.

Drafting of the manuscript: YH Ting, TY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

The research was presented as poster in the 30th World

Congress on Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology,

16-18 October 2020, and was published as an abstract in

Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology (Ting Y, Leung T, Law K, Lo T, Cheung K, So P. VP09.12: Non-visualisation of fetal

gall bladder in a Chinese cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2020;56(S1):84).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee on 3 March 2020 (CREC

Ref. No.: 2020.060).

References

1. Goldstein I, Tamir A, Weisman A, Jakobi P, Copel JA.

Growth of the fetal gall bladder in normal pregnancies.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1994;4:289-93. Crossref

2. Yayla M, Bayik RN. Undetectable gall bladder in fetus: what to do? Perinat J 2016;24:11-9. Crossref

3. Hertzberg BS, Kliewer MA, Maynor C, et al. Nonvisualization of the fetal gallbladder: frequency and

prognostic importance. Radiology 1996;199:679-82. Crossref

4. Lehtonen L, Svedström E, Kero P, Korvenranta H. Gall

bladder contractility in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child

1993;68(1 Spec No):43-5. Crossref

5. Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, et al. Practice

guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester

fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2011;37:116-26. Crossref

6. Australasian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine.

Guidelines for the performance of second (mid) trimester

ultrasound. 2018. Available from: https://www.asum.com.

au/files/public/SoP/curver/Obs-Gynae/Guidelines-for-the-Performance-of-Second-Mid-Trimester-Ultrasound.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

7. NHS Mid and South Essex, University Hospitals Group.

NHS Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme: National

Standards and Guidance for England. Guidelines for

performing the 18 weeks and 0 days to 20 weeks and 6 days

gestation fetal anomaly scan. 2015. Available from: https://www.meht.nhs.uk/EasysiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=17955&type=Full&servicetype=Attachment. Accessed

24 Aug 2020.

8. Cargill Y, Morin L. No. 223—Content of a complete routine

second trimester obstetrical ultrasound examination and

report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2017;39:e144-9. Crossref

9. Chan YM, Leung TN, Leung TY, Fung TY, Chan LW,

Lau TK. The utility assessment of Chinese pregnant

women towards the birth of a baby with Down syndrome

compared to a procedure-related miscarriage. Prenat

Diagn 2006;26:819-24. Crossref

10. Chan YM, Chan OK, Cheng YK, Leung TY, Lao TT,

Sahota DS. Acceptance towards giving birth to a child with

beta-thalassemia major—a prospective study. Taiwan J

Obstet Gynecol 2017;56:618-21. Crossref

11. Di Pasquo E, Kuleva M, Rousseau A, et al. Outcome of

non-visualization of fetal gallbladder on second-trimester

ultrasound: cohort study and systematic review of

literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;54:582-8. Crossref

12. Hartley JL, Davenport M, Kelly DA. Biliary atresia. Lancet

2009;374:1704-13. Crossref

13. Hsiao CH, Chang MH, Chen HL, et al. Universal screening

for biliary atresia using an infant stool color card in Taiwan.

Hepatology 2008;47:1233-40. Crossref

14. Zhan J, Chen Y, Wong KK. How to evaluate diagnosis

and management of biliary atresia in the era of liver

transplantation in China. World Jnl Ped Surgery

2018;1:e000002. Crossref

15. Mirtajani SB, Farnia P, Hassanzad M, Ghanavi J, Farnia P,

Velayati AA. Geographical distribution of cystic fibrosis;

the past 70 years of data analysis. Biomed Biotechnol Res J

2017;1:105-12. Crossref

16. Leung GK, Ying D, Mak CC, et al. CFTR founder mutation

causes protein trafficking defects in Chinese patients with

cystic fibrosis. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2016;5:40-9. Crossref

17. Chen M, Leung TY, Sahota DS, et al. Ultrasound

screening for fetal structural abnormalities performed by

trained midwives in the second trimester in a low-risk

population—237-an appraisal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

2009;88:713-9. Crossref

18. Chalouhi GE, Muller F, Dreux S, Ville Y, Chardot C.

Prenatal non-visualization of fetal gallbladder: beware of

biliary atresia! Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:237-40. Crossref

19. Chau MH, Cao Y, Kwok YK, et al. Characteristics and

mode of inheritance of pathogenic copy number variants

in prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:493.

e1-11. Crossref

20. Zhu X, Chen M, Wang H, et al. Clinical utility of expanded

noninvasive prenatal screening and chromosomal

microarray analysis in high risk pregnancies. Ultrasound

Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:459-465. Crossref

21. Grati FR, Molina Gomes D, Ferreira JC, et al.

Prevalence of recurrent pathogenic microdeletions and

microduplications in over 9500 pregnancies. Prenat Diagn

2015;35:801-9. Crossref

22. Muller F, Gauthier F, Laurent J, Schmitt M, Boué J.

Amniotic fluid GGT and congenital extrahepatic biliary

damage. Lancet 1991;337:232-3. Crossref

23. Bardin R, Ashwal E, Davidov B, Danon D, Shohat M,

Meizner I. Nonvisualization of the fetal gallbladder: can

levels of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in amniotic fluid

predict fetal prognosis? Fetal Diagn Ther 2016;39:50-5. Crossref

24. Dreux S, Boughanim M, Lepinard C, et al. Relationship

of non-visualization of the fetal gallbladder and amniotic

fluid digestive enzymes analysis to outcome. Prenat Diagn

2012;32:423-6. Crossref

25. Burc L, Guibourdenche J, Luton D, et al. Establishment

of reference values of five amniotic fluid enzymes.

Analytical performances of the Hitachi 911. Application to

complicated pregnancies. Clin Biochem 2001;34:317-22. Crossref

26. Bardin R, Danon D, Tor R, Mashiach R, Vardimon D,

Meizner I. Reference values for gamma-glutamyl-transferase

in amniotic fluid in normal pregnancies. Prenat

Diagn 2009;29:703-6. Crossref

27. Muller F, Bernard P, Salomon LJ, et al. Role of fetal blood

sampling in cases of non-visualization of fetal gallbladder.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:743-4. Crossref

28. Ruiz A, Robles A, Salva F, et al. Prenatal nonvisualization of

the gallbladder: a diagnostic and prognostic dilemma. Fetal

Diagn Ther 2017;42:150-2. Crossref

29. Chan YM, Leung TY, Cao Y, et al. Expanded carrier

screening using next generation sequencing of 123 Hong

Kong Chinese families: a pilot study. Hong Kong Med J

2021;27:177-83. Crossref