Hong Kong Med J 2021 Jun;27(3):184–91 | Epub 11 Jun 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Effects of pill splitting training on drug physiochemical properties, compliance, and clinical outcomes in the elderly population: a randomised trial

Vivian WY Lee, PharmD, BCPS1; Joyce TS Li, BPharm1; Felix YH Fong, BPharm1; Bryan PY Yan, FHKAM (Medicine)2

1 Centre for Learning Enhancement and Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Vivian WY Lee (vivianlee@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to provide information about the clinical and physiochemical

effects of pill splitting training in elderly cardiac

patients in Hong Kong.

Methods: A parallel study design was adopted.

Patients taking lisinopril, amlodipine, simvastatin,

metformin, or perindopril who needed to split pills

were recruited from the Prince of Wales Hospital.

Patients were divided into two groups at their first

visit. Patients in group A split drugs using their

own technique, whereas patients in group B used

pill cutters after relevant training until their next

follow-up visit. The primary outcome was the

change in drug content between before and after

the pill splitting training. Assays were performed to

determine the drug content. Secondary outcomes

were the changes in clinical outcomes, patients’

attitudes and acceptance towards pill splitting, and

patients’ knowledge about pill splitting.

Results: A total of 193 patients were recruited, and

101 returned for the follow-up visit. The percentage

of split tablets falling within the assay limits

increased from 39.13% to 47.82% (P=0.523) in group

A and from 48.94% to 51.06% (P=1.000) in group B. The changes did not reach statistical significance.

As for clinical outcomes, the mean triglyceride level

decreased from 1.62±1.05 to 1.36±0.80 (P=0.049),

whereas the mean heart rate increased significantly

from 73.97±11.01 to 77.92±12.72 (P=0.026). Changes

in other parameters were not significant.

Conclusion: This study highlights the high variability

of drug content after pill splitting. Pills with dosages

that do not require splitting would be preferable,

considering patients’ preference. Patients should be

educated to use pill cutters properly if pill splitting is

unavoidable.

New knowledge added by this study

- There is high variability of drug content after pill splitting.

- Patients prefer to take pills that do not require splitting.

- Patients should be supplied with formulations that do not require splitting if possible.

- Patients should be educated to use pill cutters properly if pill splitting is unavoidable.

Introduction

Pill splitting by patients is common globally. A

German study observed that 24.1% of all drugs

required splitting,1 and a Swiss study found that

10% of all discharged prescriptions contained pill

splitting.2 In Sweden, 10% of 600 000 investigated

prescriptions required splitting, and over 30% of

the Swedish patients stated that they had problems

dividing the tablets.3 The observed prevalence

of pill splitting has been observed to range from

10% to >35% worldwide1 4 5 6 and was even higher in

elderly patients (35-67%).6 7 One of the reasons for pill splitting is cost saving because it may result

in institutions not needing to stock too many

drug items in their formularies.1 In addition, drug

splitting may achieve dose flexibility, particularly

for patients requiring frequent dosing adjustment.8

Furthermore, some dosages may not be commercially

available, especially those for off-label drug use.

In these cases, splitting drugs may be essential.9 10 11

Nevertheless, it can also create other clinical issues

including medication non-compliance, difficulties

experienced by patients in handling unscored pills,

drugs that crumble after splitting, and inappropriate drug splitting of extended release formulations,

which may lead to treatment failure or toxicity.12 A

published study reported that most hypertensive

patients preferred not to split pills and that over 70%

of patients were willing to pay more for medications

with dosages that they did not need to split.13

Limited published studies have addressed this drug-related

problem. In this study, we aimed to identify

the effects of pill splitting on drug physiochemical

properties and clinical outcomes among elderly

cardiac patients.

Methods

Study design

A parallel design was adopted in this study. Patients were recruited from the Cardiac or Hypertension

clinics of the Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong.

After medical records review, it was found that

lisinopril, amlodipine, simvastatin, metformin,

and perindopril were among the most commonly

prescribed medications that required splitting in

the two clinics. Therefore, patients who needed to

split their pills when taking lisinopril, amlodipine,

simvastatin, metformin, or perindopril were

recruited. Patients were randomised into either

group A (pill splitting with self-technique) or group

B (pill splitting with instructions and training) after

their first clinic visit. All patients were asked to sign

an informed consent form before enrolment. Group

A patients were asked to split drugs using their own technique and continue until their next clinic visit.

Group B patients were given proper instruction by

pharmacists or pharmacy students on using pill

cutters at their first visit and were asked to cut their

pills accordingly until their next clinic visit. Patients

watched a 2-minute video that explained the reasons

for using pill cutters and described the proper way

to open the pill cutter, position the drug in the pill

cutter, clean the pill cutter, and store the split pills.

Subsequently, the pharmacist answered patients’

enquiries regarding the video or other questions

related to pill splitting. The current study did not

change any drug or dosage of the patient’s existing

treatment regimens. Follow-up clinic visits were

scheduled with mean duration between first and

follow-up clinic visits of 23.1±7.3 weeks.

Participants

Chinese patients aged ≥65 years, both male and

female, and currently prescribed one or more of

metformin, lisinopril, perindopril, amlodipine, or

simvastatin (which require splitting) were included

in the current study. Patients with dementia or severe

physical limitations such as hemiplegia, blindness,

or upper limb contractures were excluded from the

study.

In our pilot study, we found that the change in

drug assays of metformin, atenolol, and amlodipine

varied from 52.7% to 147.2% after splitting.14 In our

previously published study, systolic blood pressure

decreased significantly (from 152.38±18.80 mm Hg

to 147.04±20.72 mm Hg, P=0.021) after pharmacist

intervention.15 The sample size for the primary

outcome was calculated based on a population

standard deviation of 0.75, and that for the secondary

outcomes was based on a population standard

deviation of 0.85. To achieve a 5% significance level

and 80% power, 30 and 45 patients in each group

would be needed for the primary and secondary

outcomes, respectively. We expected a 10% dropout

rate, and therefore, at least 80 patients were recruited

for each group. There were 193 total participants in

this study.

The participants were randomised into group

A or B using a computerised dynamic allocation

programme and stratification according to types of

medications taken, sex, age, and visit dates to ensure

balanced patient allocation. All operations were

performed by the same pharmacist who conducted

the survey.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the change of drug

content before and after the pill splitting training.

At baseline, patients in groups A and B were asked

to split three tablets of the drugs that they were

currently taking using their usual technique. At

follow-up visit, group A patients were asked to split three tablets using their own technique, and group B

patients were asked to split three tablets using a pill

cutter. Two halved tablets were randomly selected for

analysis each time. The halved tablets were weighed,

and standard drug assays were performed. The drug

content of metformin was assessed by ultraviolet-visible

spectrophotometry; that of amlodipine,

simvastatin, and perindopril was assessed by ultra-performance

liquid chromatography; and that of

lisinopril was assessed by high-performance liquid

chromatography.

The secondary outcomes were the changes in

clinical outcomes between before and after the pill

splitting training, including the change in blood

pressure measurements, haemoglobin A1c, and

cholesterol levels, the changes in patients’ attitudes

towards and acceptance of pill splitting, and the

changes in patients’ knowledge about pill splitting.

Haemoglobin A1c and lipid levels were usually

collected in hospital 1 week before patients’ clinic

visit. Upon initiating their clinic visits, patients had

their blood pressures measured in the hospital’s

nurse station before they met their physicians. Blood

pressure, haemoglobin A1c, and cholesterol levels

were collected at baseline and at follow-up visit, and

the patients’ knowledge about and attitudes towards

pill splitting were assessed by questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

Paired-samples t tests were used for intra-group comparisons, and independent-samples t tests

were used for inter-group comparisons of mean

tablet weight between before and after pill splitting

training. Paired-samples t tests were also used to

assess the changes in clinical outcomes. McNemar’s

test was used for intra-group comparisons, and

Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) was used for inter-group

comparisons of content uniformity, change

in patients’ acceptance towards pill splitting, and

change in patients’ knowledge about pill splitting.

A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically

significant. All analyses were performed using the

SPSS statistical programme (Windows version 25.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Results

Participants

A total of 193 eligible patients were enrolled on or before 17 January 2019, and they had follow-up

visits on or before 30 April 2019. The patients were

randomised into group A (n=106) and group B (n=87).

A total of 101 patients participated, of whom 47 from

group A and 54 from group B returned for follow-up

visit. Among them, 46 patients from group A and 47

patients from group B provided samples for assay.

The primary outcome analysis was conducted on

those patients, and the secondary outcomes analysis was conducted on the 101 patients who returned for

follow-up visit. The patients’ demographic data are

shown in Table 1.

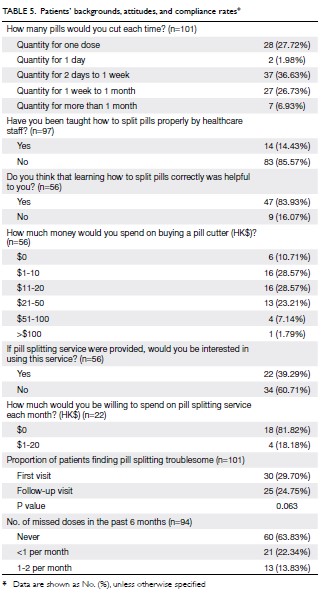

Table 1. Patients’ demographics at first (baseline) and follow-up clinic visits (mean duration 23.1 ± 7.3 weeks)

Drug content

The primary outcome was the change of drug content between before and after the pill splitting training.

Patients were asked to split three tablets during each

visit. Two halved tablets were randomly selected as

samples. The samples were weighed, and assays were

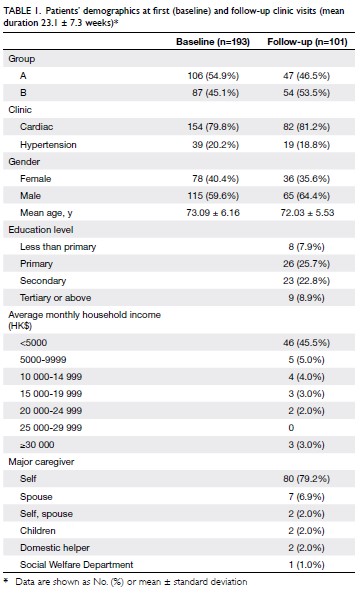

performed. The mean weight of the halved tablets

at baseline and at follow-up visit is documented

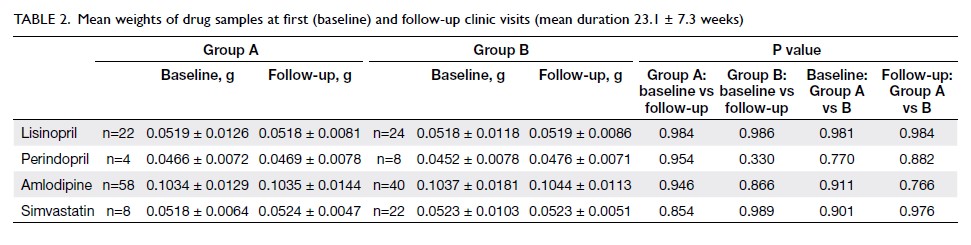

in Table 2. Table 3 shows the percentage of halved

tablets that were within the assay specifications at

baseline and at follow-up visit. The percentage of samples with both halved tablets within range was

compared between groups A and B. In group A,

the percentage in range increased from 39.13% to

47.82% (P=0.523), and the corresponding increase

for group B was from 48.94% to 51.06% (P=1.000).

The difference in drug assay results between groups

A and B at baseline (P=0.406) and at follow-up visit

(P=0.837) also did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2. Mean weights of drug samples at first (baseline) and follow-up clinic visits (mean duration 23.1 ± 7.3 weeks)

Table 3. Percentage of halved tablets within assay specifications at first (baseline) and follow-up clinic visits (mean duration 23.1 ± 7.3 weeks)

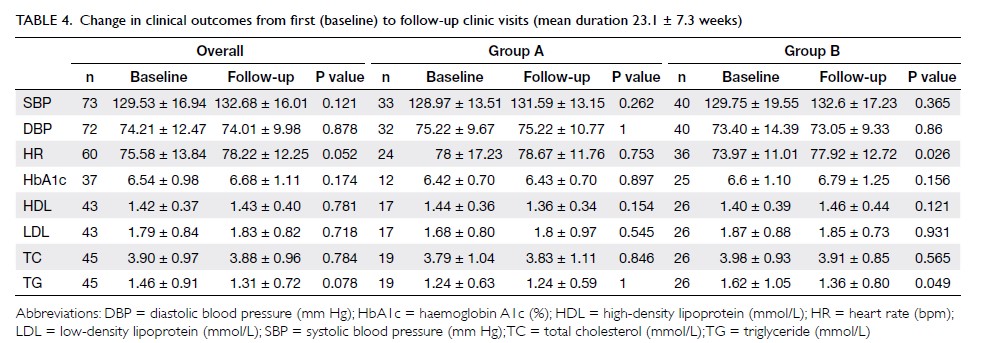

Clinical outcomes

The correlation between pill cutting training and

clinical outcomes is summarised in Table 4. The

mean triglyceride in group B decreased significantly from 1.62±1.05 to 1.36±0.80 mmol/L (P=0.049),

whereas the mean heart rate increased significantly

from 73.97±11.01 to 77.92±12.72 bpm (P=0.026).

In group B, there was also improvement in the

mean diastolic blood pressure (from 73.40±14.39

to 73.05±9.33 mm Hg), high-density lipoprotein

(from 1.40±0.39 to 1.46±0.44 mmol/L), low-density

lipoprotein (from 1.87±0.88 to 1.85±0.73 mmol/L),

and total cholesterol (from 3.98±0.93 to

3.91±0.85 mmol/L), but those differences did

not reach statistical significance. In the overall

cohort, improvements were seen in diastolic blood

pressure (from 74.21±12.47 to 74.01±9.98 mm Hg), high-density lipoprotein (from 1.42±0.37 to

1.43±0.40 mmol/L), total cholesterol (from

3.90±0.97 to 3.88±0.96 mmol/L), and triglyceride

(from 1.46±0.91 to 1.31±0.72 mmol/L), but the

changes did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4. Change in clinical outcomes from first (baseline) to follow-up clinic visits (mean duration 23.1 ± 7.3 weeks)

Patients’ backgrounds, attitudes, and

knowledge

In total, 57.43% of patients split their pills with their bare hands, followed by pill cutters (24.75%), knives

(13.86%), and scissors (10.89%). The major reasons

for not using pill cutters included: (1) the current

method could split pills evenly (68.18%), (2) using

pill cutters was time consuming (34.09%), and (3) the

pills could not be split evenly by pill cutters (15.91%).

The major reasons for using pill cutters included:

(1) pills could be cut evenly (80.95%) and (2) the

patient was able to exert force more easily (33.33%).

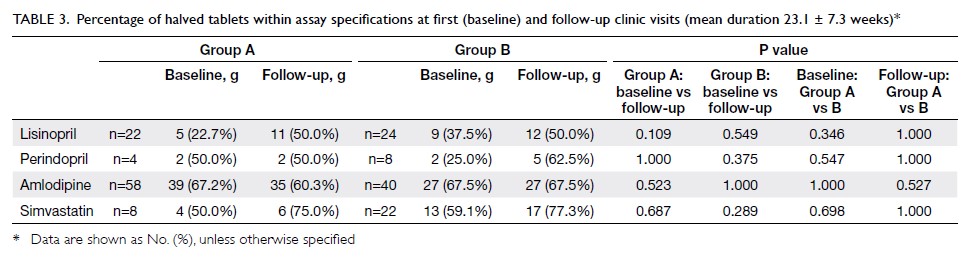

In total, 29.70% and 24.75% of patients found pill

splitting troublesome at baseline and at follow-up

visit, respectively (the difference was not significant,

P=0.063). The three major problems encountered

by patients while splitting pills were (1) difficulty

splitting the pills evenly (17.00%), (2) the pills easily

fragmented (10.00%), and (3) difficulty seeing the

pills clearly, as they were too small (9.00%). Overall,

61.00% of the patients claimed that they had no

difficulties. Nevertheless, 98.21% preferred to take

tablets with exact dosages so that no splitting would

be required. Patients’ responses to other questions

are listed in Table 5.

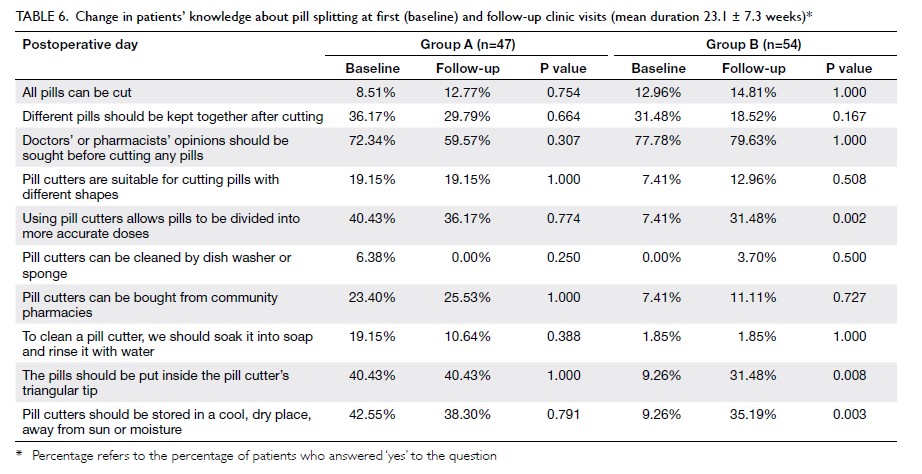

Table 6 shows that a significantly higher portion

of patients in group B had a correct understanding of

the following three questions after training: ‘Using

pill cutters allows pills to be divided into more

accurate doses’ (from 7.41% to 31.48%; P=0.002);

‘The pills should be put into the triangular tip of

the pill cutter’ (from 9.26% to 31.48%; P=0.008); and

‘Pill cutters should be stored in a cool and dry place,

away from sun or moisture’ (from 9.26% to 35.19%;

P=0.003). In contrast, patients in group A did not

show a statistically significant improvement in their

understanding of any question. During the interview

and evaluation of patients’ knowledge about pill

splitting at baseline and at follow-up visit, we did not

detect any patients with major physical or cognitive

abnormalities.

Table 6. Change in patients’ knowledge about pill splitting at first (baseline) and follow-up clinic visits (mean duration 23.1 ± 7.3 weeks)

Discussion

Tablet splitting is a common practice in in-patient and out-patient settings,16 and it may be desirable

in terms of dose adjustment, cost saving, and

ease of swallowing.3 11 12 17 18 19 20 Nevertheless, it has

been reported that splitting pills may cause drug

instability, loss of drug due to powdering, uneven

dosage, and reduced drug strength.21 22 It is generally

understood that using tablet splitting devices can

provide a more consistent dose.10 21 Previous studies have identified some characteristics that might affect

the quality of halved tablets. Coated, unscored, and

small tablets were found to be more difficult to cut.23

Individual pill cutting skill was another crucial factor

that determined tablets’ uniformity.23 In the current

study, only 24.75% of patients split pills using pill

cutters, and only 14.43% of patients had received

pill splitting training. Therefore, it is likely that the

drug content in the halved tablets did not reach assay

standards.

Previous studies mainly focused on the weight

deviations among halved tablets, not on drug

content.21 22 One study showed that more than

one-third of sampled half-tablets did not meet the United

States Pharmacopeia specifications.24 The measured

drug content variations among half-tablets were:

warfarin sodium (90.01%-109.40%), simvastatin

(95.21%-111.35%), metoprolol succinate (82.77%-115.92%), metoprolol tartrate (94.83%-112.37%),

citalopram (96.50-111.93%), and lisinopril (81.15%-125.72%). In another study, five of eight drugs failed

to meet European Pharmacopoeia recommendations

for tablet weight deviation after splitting, with 25%

of samples deviating by >15% and 10% of samples

deviating by >25%.23 The study drugs used were

phenobarbitone (maximum deviation: 80.45%),

digoxin (maximum deviation: 56.69%), chloroquine

(maximum deviation: 48.97%), atenolol (maximum

deviation: 45.37%), and doxycycline (maximum

deviation: 43.97%). In the present study, both halves

of the tablet were within the assay standard at baseline

for 39.13% and 48.94% of the patients in groups A

and B, respectively. After training, this percentage

increased to 47.82% and 51.06%, respectively, but the

improvement was not significant, and the percentage

of tablets in range was still relatively low. The results

corroborated those of previous studies.

Few studies have examined the effect of patient

education on the drug content of split pills.25 26 In the

current study, we found no significant improvement

in content uniformity after pill splitting training. This

may be because our patients were elderly patients who may not have been able to perform the task well

after a single training session. Content uniformity

after pill splitting may be improved if pills are split by

pharmacists or qualified staff. A study of paediatric

pharmacists suggested that tablets >8 mm could be

split once to achieve an approximate half dose for

paediatric use.27 Another study found a significant

difference in splitting accuracy between nurses

and laypersons.23 Nevertheless, only 39.29% of that

study’s patients were eager to partake of pill splitting

service, and only 18.18% were willing to pay extra

money for it. Therefore, pill cutting service may not

be practical without a financial incentive.

Triglyceride levels decreased significantly

and heart rate increased significantly in group B

patients after the intervention. Nevertheless, we

did not evaluate the patients’ diet consumption or

exercise levels, which may impact their triglyceride

levels. No significant change in clinical outcomes

was observed in other groups or other parameters.

Because the studied drugs were lisinopril,

perindopril, simvastatin, and amlodipine, which

are not narrow-therapeutic-index drugs, these

results were predictable and coincide with other

studies that concluded that drugs with long half-life

and wide therapeutic index are less likely to be

affected.20 28 In view of the high variability of blood

pressure measurements in the clinic, all patients

were originally instructed to conduct daily blood

pressure measurements at home using a portable

blood pressure monitor. However, many patients did

not measure their blood pressure daily or did not keep a proper self-record, so the clinical outcomes

relied on the readings at clinic visits, which may not

be consistent with their usual readings. In addition,

management of chronic diseases like hypertension,

diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidaemia could be

influenced by multiple factors, and 3 months was

a relatively short period for observation. The effect

of drug content deviation after splitting on clinical

outcomes may be more obvious in antibiotics or drugs

with narrow therapeutic index (eg, digoxin).23 29 30

In the current study, we focused on the effect

of pill splitting on drug content. Nevertheless, pill

splitting may have other effects on drugs. The pill

may carry a bitter taste, as the coating is broken,

and the active ingredients may be more susceptible

to moisture after exposure.31 Over 70% of patients

prepared a sufficient quantity of pills for more than

1 day each time. In total, 36.63% of patients cut for

2 days to 1 week, 26.73% cut for 1 week to 1 month,

and 6.93% cut for more than 1 month each time.

Exposing the cut pills for too long may increase the

risk of crushing or cracking.19 In total, 83.93% of

patients found pill splitting training helpful, and the

intervention produced significant improvement in

patients’ knowledge about pill splitting. This study

has identified the major difficulties encountered by

patients and the reasons behind their choices. Those

problems should be addressed in future patient

education. More than half of patients split pills with

their bare hands, and the majority of patients who did

not use pill cutters thought their own methods could

divide pills evenly and that the use of pill cutters

was time consuming. The major obstacles patients

faced were the difficulties in splitting pills evenly

and that the pills fragmented easily. Overall, 98.21%

of patients preferred to take tablets with the exact

dosage instead of splitting pills. Previous studies

also found that dispensing the exact dosage would

be more favourable.23 32 Nevertheless, if pill splitting

is unavoidable, pharmacists should encourage

patients to split coated, unscored, or irregularly

shaped tablets with pill cutters to reduce crushing

or fragmenting. Pharmacists should also educate

patients about the appropriate way to use and clean

pill cutters and remind patients to seek doctors’ or

pharmacists’ advice before cutting any pills.21 23 33

This project has several limitations. First, the

participants’ dropout rate was high, which might

result in attrition bias. Compared with group A, a

higher proportion of group B patients returned

for follow-up visits. The statistically significant

improvement in clinical outcomes among group B

patients might be caused by their higher awareness

about their own health instead of the effectiveness of

the pill splitting method. There were limited human

resources to make phone calls to patients between

the baseline and face-to-face follow-up visits, which

could have served as a reminder for patients to attend follow-up visits and perform home monitoring of

their blood pressure and their pill splitting methods.

Second, dietary consumption and exercise

levels were not evaluated, even though they may affect

the clinical outcomes. Third, participants’ education

level, household income, and major caregivers were

not collected at baseline. Only approximately 65% of

participants who attended follow-up visits provided

such information. These confounding factors might

affect patients’ ability to understand and memorise

the steps of using pill cutters, thus affecting the

content uniformity of their split pills. The effects of

patients’ characteristics on their knowledge and pill

splitting skills were not assessed in the current study.

Conclusion

This study revealed that content uniformity can

hardly be achieved after pill splitting by patients.

No significant difference in clinical outcomes was

observed after pill splitting training. It is preferable

for pills with doses that do not require splitting

to be provided, considering the assay results and

patients’ preference. Currently, there is inadequate

patient education about pill splitting. Pharmacists

should educate patients to use pill cutters properly if

splitting is inevitable.

Author contributions

Concept or design: VWY Lee, FYH Fong, BPY Yan.

Acquisition of data: VWY Lee, FYH Fong, BPY Yan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JTS Li.

Drafting of the manuscript: JTS Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: VWY Lee.

Acquisition of data: VWY Lee, FYH Fong, BPY Yan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JTS Li.

Drafting of the manuscript: JTS Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: VWY Lee.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, BPY Yan was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank the technicians at the School of Pharmacy, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong for carrying out the drug

physiochemical tests and the staff at Prince of Wales Hospital

for arranging the logistics for patient counselling.

Funding/support

This study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund, Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government

(#14152111). The funder had no role in study design, data

collection/analysis/interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Clinical trial registration

no.: CREC Ref No. 2017.014). Patient consent was obtained

upon enrolment. The trial protocol can be obtained as

requested.

References

1. Quinzler R, Gasse C, Schneider A, Kaufmann-Kolle P, Szecsenyi J, Haefeli WE. The frequency of inappropriate

tablet splitting in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol

2006;62:1065-73. Crossref

2. Berg C, Ekedahl A. Dosages involving splitting tablets: common but unnecessary? J Pharm Health Serv Res

2010;1:137-41. Crossref

3. Rodenhuis N, De Smet PA, Barends DM. The rationale of scored tablets as dosage form. Eur J Pharm Sci 2004;21:305-

8. Crossref

4. Rodenhuis N, de Smet PA, Barends DM. Patient experiences with the performance of tablet score lines

needed for dosing. Pharm World Sci 2003;25:173-6. Crossref

5. Stanković I, Pešić M, Lalić M. Breaking of tablets as a cost-saving strategy. Timočki Medicinski Glasnik 2007;32:5-10.

6. Fischbach MS, Gold JL, Lee M, Dergal JM, Litner GM, Rochon PA. Pill splitting in a long-term care facility. CMAJ

2001;164:785-6.

7. Denneboom W, Dautzenberg MG, Grol R, De Smet PA.

User-related pharmaceutical care problems and factors

affecting them: the importance of clinical relevance. J Clin

Pharm Ther 2005;30:215-23. Crossref

8. Peek BT, Al-Achi A, Coombs SJ. Accuracy of tablet splitting by elderly patients. JAMA 2002;288:451-2. Crossref

9. Duncan MC, Castle SS, Streetman DS. Effect of tablet splitting on serum cholesterol concentrations. Ann

Pharmacother 2002;36:205-9. Crossref

10. Rindone JP. Evaluation of tablet-splitting in patients taking lisinopril for hypertension. JCOM Wayne PA 2000;7:22-30.

11. Gee M, Hasson NK, Hahn T, Ryono R. Effects of a tablet-splitting

program in patients taking HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitors: analysis of clinical effects, patient satisfaction,

compliance and cost avoidance. J Manag Care Pharm

2002;8:453-8. Crossref

12. Fawell NG, Cookson TL, Scranton SS. Relationship

between tablet splitting and compliance, drug acquisition

costs, and patient acceptance. Am J Health Syst Pharm

1999;56:2542-5. Crossref

13. McDevitt JT, Gurst AH, Chen Y. Accuracy of tablet

splitting. Pharmacotherapy 1998;18:193-7.

14. Lee VW, Yu Y, Tang L, Yan B. Impact of pill-splitting

training on drug physiochemical properties, compliance

and clinical outcomes in elderly population–a cross-over

cohort study. Value Health 2013;16:A514. Crossref

15. Lee VW, Pang PT, Kong KW, Chan PK, Kwok FL.

Impact of pharmacy outreach services on blood pressure

management in the elderly community in Hong Kong.

Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:175-81. Crossref

16. Crawford DJ. Is tablet splitting safe? Nursing made

incredibly easy 2011;9:18-20. Crossref

17. Cohen CI, Cohen SI. Potential savings from splitting newer antidepressant medications. CNS Drugs 2002;16:353-8. Crossref

18. Stafford RS, Radley DC. The potential of pill splitting to achieve cost savings. Am J Manag Care 2002;8:706-12.

19. Bachynsky J, Wiens C, Melnychuk K. The practice of splitting tablets: cost and therapeutic aspects.

Pharmacoeconomics 2002;20:339-46. Crossref

20. Helmy SA. Tablet splitting: is it worthwhile? Analysis of

drug content and weight uniformity for half tablets of 16

commonly used medications in the outpatient setting. J

Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21:76-86. Crossref

21. Verrue C, Mehuys E, Boussery K, Remon JP, Petrovic M.

Tablet-splitting: a common yet not so innocent practice. J

Adv Nurs 2010;67:26-32. Crossref

22. Rosenberg JM, Nathan JP, Plakogiannis F. Weight variability

of pharmacist-dispensed split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc

(Wash) 2002;42:200-5. Crossref

23. Elliott I, Mayxay M, Yeuichaixong S, Lee SJ, Newton PN.

The practice and clinical implications of tablet splitting in

international health. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:754-60. Crossref

24. Hill SW, Varker AS, Karlage K, Myrdal PB. Analysis of

drug content and weight uniformity for half-tablets of

6 commonly split medications. J Manag Care Pharm

2009;15:253-61. Crossref

25. Gharaibeh SF, Tahaineh L. Effect of different splitting

techniques on the characteristics of divided tablets of five

commonly split drug products in Jordan. Pharm Pract

(Granada) 2020;18:1776. Crossref

26. Ashrafpour R, Ayati N, Sadeghi R, et al. Comparison of

treatment response achieved by tablet splitting versus

whole tablet administration of levothyroxine in patients

with thyroid cancer. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol

2018;6:108-12. Crossref

27. Andersson ÅC, Lindemalm S, Eksborg S. Dividing the

tablets for children—good or bad? Pharm Methods

2016;7:23-7. Crossref

28. Chou CL, Hsu CC, Chou CY, Chen TJ, Chou LF, Chou YC. Tablet splitting of narrow therapeutic index

drugs: a nationwide survey in Taiwan. Int J Clin Pharm

2015;37:1235-41. Crossref

29. Simpson JA, Watkins ER, Price RN, Aarons L, Kyle DE, White NJ. Mefloquine pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic

models: implications for dosing and resistance. Antimicrob

Agents Chemother 2000;44:3414-24. Crossref

30. White NJ, Pongtavornpinyo W, Maude RJ, et al. Hyperparasitaemia and low dosing are an important

source of anti-malarial drug resistance. Malar J 2009;8:253. Crossref

31. Margiocco ML, Warren J, Borgarelli M, Kukanich B.

Analysis of weight uniformity, content uniformity and

30-day stability in halves and quarters of routinely

prescribed cardiovascular medications. J Vet Cardiol

2009;11:31-9. Crossref

32. Madathilethu J, Roberts M, Peak M, Blair J, Prescott R,

Ford JL. Content uniformity of quartered hydrocortisone

tablets in comparison with mini-tablets for paediatric

dosing. BMJ Paediatr Open 2018;2:e000198. Crossref

33. Allemann SS, Bornand D, Hug B, Hersberger KE, Arnet I.

Issues around the prescription of half tablets in Northern

Switzerland: the irrational case of quetiapine. Biomed Res

Int 2015;2015:602021. Crossref