Hong Kong Med J 2021 Oct;27(5):330–7 | Epub 5 Oct 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Burnout and well-being in young doctors in Hong

Kong: a territory-wide cross-sectional survey

Kenny YH Kwan, BMBCh (Oxon), FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Loretta WY Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)2; PW Cheng, MB, BS, FHKAM (Psychiatry)3; Gilberto KK Leung, MB, BS (Lon), FHKAM (Surgery)4; CS Lau, MB, ChB (Dundee), FHKAM (Medicine)5; for the Young Fellows Chapter of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine

1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Family Medicine, Private Practice

3 Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

5 Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Kenny YH Kwan (kyhkwan@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This territory-wide study evaluated the level of burnout and health status among young doctors in Hong Kong.

Methods: All young doctors in Hong Kong, defined

as residents-in-training or doctors within 10 years

of their specialist registration, were invited to

participate in an online cross-sectional survey.

This survey used standardised questionnaires

including the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI)

for burnout, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for

depression, and general health questionnaires.

Results: In total, 514 doctors completed the survey;

284 were doctors within 10 years of their specialist

registration, while 230 were residents-in-training.

There were 277 women (54%); among all respondents,

the mean age was 33.7 ± 6.1 years. Using a CBI subscale

cut-off score of ≥50 (moderate and higher), 72.6%

(n=373) of respondents reported personal burnout;

70.6% (n=363) of respondents reported work-related

burnout; and 55.4% (n=285) of respondents reported

client-related burnout. Furthermore, 24% (n=125) of

respondents were “somewhat dissatisfied” with their

present job position; 4% (n=19) of respondents were

“very dissatisfied” with their present job position.

The prevalence of depression among respondents

was 21% (n=110).

Conclusions: this territory-wide cross-sectional

survey of young doctors in Hong Kong, a high

prevalence of burnout was identified among young

doctors; respondents exhibited a considerable level

of depression and substantial dissatisfaction with

their current positions. Strategies to address these

problems must be formulated to ensure the future

well-being of the medical and dental workforce in

Hong Kong.

New knowledge added by this study

- There is a high prevalence of burnout among young doctors in Hong Kong; of 514 survey respondents, 72.6% reported personal burnout, 70.6% reported work-related burnout, and 55.4% reported client-related burnout.

- The prevalence of depression among young doctors (21% in this study) was considerably higher than among the general population in Hong Kong (8.4% in a previous study).

- Overall, 28% of respondents were either “somewhat dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with their present job position.

- Changes to the number of working hours per week and extent of clinical responsibilities may help to reduce burnout among junior doctors.

- Efforts to promote stronger social networks among junior doctors and their communities may reduce the risk of burnout, although further studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

- Although the respondents did not indicate reliance on substance or alcohol abuse, there is a need for greater workplace emphasis on positive health and lifestyle behaviours to reduce the risk of burnout among junior doctors.

Introduction

Burnout among doctors is increasingly recognised

as a serious threat to medical and dental practice

across all specialties; its prevalence is increasing worldwide.1 Burnout is a spectrum of clinical

syndromes that were first categorised into three

dimensions by Maslach as emotional exhaustion,

depersonalisation, and a low sense of personal accomplishment.2 Subsequently, it was added to

the International Classification of Diseases as a

syndrome that results from poorly managed chronic

workplace stress.3

Burnout among doctors can lead to decreased

effectiveness and shortening of professional lifespan.4

Burnout exacerbates negative emotions, thereby

impeding cognitive performance; it may result in

biased decision making. Hence, the well-being of

doctors is important for maintaining manpower,

quality of care, and equity of care delivery. Multiple

studies in different countries have shown that the

incidence of burnout among doctors is rising. In

the US, a Medscape nationwide survey showed that

59% of emergency medicine doctors experienced

burnout symptoms, and the incidence had increased

steadily over time.1 In Australia, the National Mental

Health Survey found that the level of very high

psychological distress was significantly greater in

doctors (3.4%) than in the general population (2.6%)

or other professionals (0.7%).5 A cross-sectional

online survey in the United Kingdom also revealed

a high rate of mental health disorders among junior

doctors and medical students.6

To our knowledge, studies regarding well-being

and burnout among doctors in Asia are

limited. Gan et al7 performed a cross-sectional

study of general practitioners in Hubei, China;

they found a combined prevalence of 2.46% across

all three dimensions of emotional exhaustion,

depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment. However, that study only included doctors within a

single specialty in one province. Huang et al8 found

the prevalences of personal burnout and client-related

burnout were 44.0% and 14.8%, respectively,

among residents in Taiwan; however, they used a

non-standardised questionnaire. In Hong Kong, a

previous cross-sectional survey showed that 31.4%

of respondents among doctors in the public sector

had a high rate of burnout, but the sampling criteria

were random and non-specific; moreover, that study

did not include a substantial proportion of doctors

who worked in the private sector.9 Another survey

also suggested that burnout was prevalent among

doctors in Hong Kong, but it only included graduates

from one medical school in Hong Kong.10

Hence, this study aimed to evaluate the

prevalence of burnout in the Hong Kong medical

and dental workforce by administering standardised

questionnaires to a broad population of residents-in-training and doctors within 10 years of their

specialist registration. The study also explored well-being

among doctors in terms of job satisfaction,

depression, lifestyle behaviours, and factors

associated with these states.

Methods

Survey and study population

In this study, all doctors within 10 years of their

specialist registration registered with the Hong

Kong Academy of Medicine, as well as residents-in-training registered with one of the Academy’s

15 constituent Colleges, were invited to complete a

voluntary cross-sectional survey between February

2019 and June 2019. The cut-off of 10 years was

selected because the Hong Kong Academy of

Medicine considers doctors within 10 years of

their specialist registration to be “young Fellows”.

The survey consisted of self-reported demographic

data, year of entry into medical school, and current

professional details. Burnout was assessed using the

validated Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI).11

Depression was assessed using the Patient Health

Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).12 Lifestyle factors were

assessed with reference to the respondents’ drinking

habits, sleep patterns, and levels of both exercise

and activities. Items concerning job satisfaction

and lifestyle behaviours were adapted from existing

doctor questionnaires and health surveys.13 14

An online survey was developed in-house by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative Learning

Centre for Medicine of the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine, then administered electronically.

The invitations to participate were sent via e-mail;

two separate reminder emails were sent after the

initial invitation. As an incentive, respondents were

offered coffee or food coupons after completion of

the survey. The study protocol was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster

(Ref No: UW 19-062).

Sample size calculation

PASS 2000 (NCSS, LLC., Kaysville [UT], US; www.ncss.com) power analysis software was used for

sample size calculation. The prevalence of personal

burnout among young doctors in Hong Kong was

assumed to be similar to the prevalence of personal

burnout among residents in Taiwan (44.0%)8; thus,

to achieve a 95% confidence interval (CI) with a

precision of 4.5%, 458 participants were required.

Our final sample of 514 doctors was sufficient to

achieve the desired statistical power.

Specific instruments

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory

This instrument consists of three scales that measure

personal burnout, work-related burnout, and client-related

burnout; the scales can be applied to workers

in all industries and cultures. Personal burnout

measures the degree of fatigue experienced by the

respondent, irrespective of work experience or

occupational status. Work-related burnout measures

the degree of fatigue related to work; it explores how

the respondent’s perception of work contributes

to fatigue. Client-related burnout is the perceived

degree of fatigue related to work with clients. The

burnout level is calculated as a mean score; therefore,

each scale has a value between 0 and 100. A score of

≥50 indicates a high degree of burnout.15 16 17 18

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The PHQ-9 is a depression assessment tool, which

scores each of the nine Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders IV criteria for

depression on a scale ranging from “0” (not at all)

to “3” (nearly every day). A PHQ-9 score >9 has a

reported sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 88% for

major depression.19

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of burnout is shown using point

estimates and 95% CIs. Descriptive statistics were

presented concerning demographic characteristics

and lifestyle behaviours. Bivariate logistic models

were used to describe the distinct relationships of

suicide, depression, and burnout with demographic,

educational, and professional characteristics. The

data were analysed using SPSS software (Windows

version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US).

Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Participant demographics

There were 746 total respondents; of these, 232 did not complete the entire survey and were excluded

from the analysis. Of the included 514 respondents,

284 were doctors within 10 years of their specialist

registration, while 230 were residents-in-training.

The total number of doctors within 10 years of

their specialist registration invited to participate

in the survey was 2879; thus, the response rate was

estimated as 9.9%. However, it was not possible to

calculate the response rate for residents-in-training.

The respondents included 277 women (54%); the

mean age among all respondents was 33.7 ± 6.1 years.

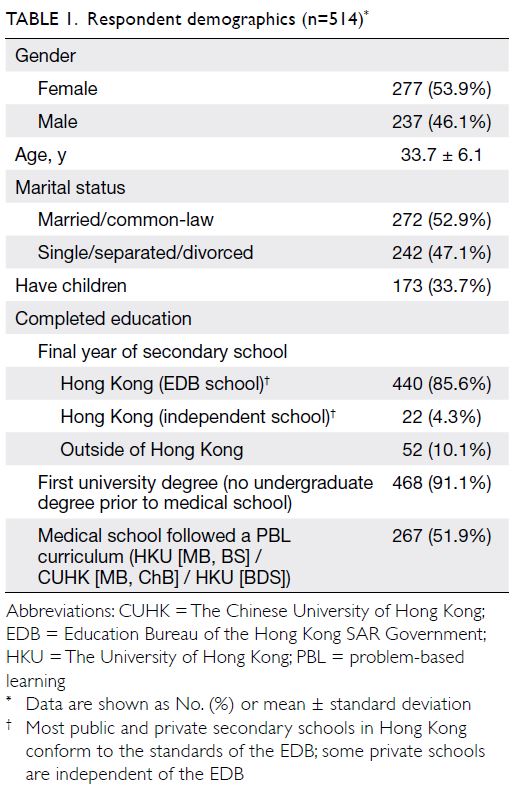

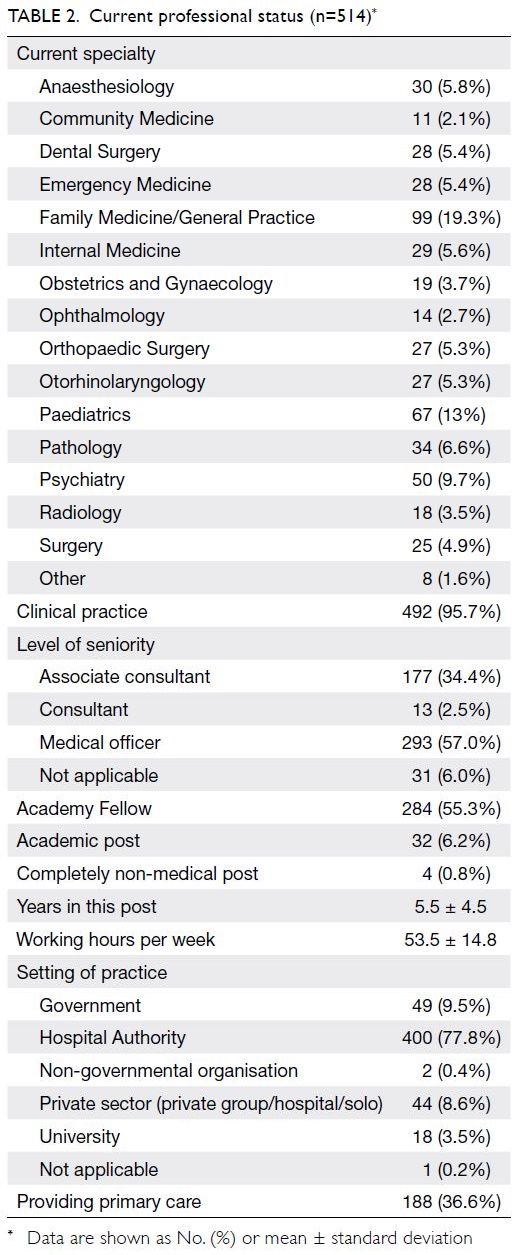

The respondents’ demographic data are summarised

in Table 1; their current professional statuses are

summarised in Table 2.

Professional satisfaction

Overall, 24% (n=125) of respondents were “somewhat dissatisfied” with their present job position, while

4% (n=19) of respondents were “very dissatisfied”

with their present job position. Furthermore, 15%

(n=76) of respondents were “somewhat dissatisfied”

with being a medical doctor, whereas 2% (n=10) of

respondents were “very dissatisfied” with being a

medical doctor. Finally, 3% (n=14) of respondents

indicated they planned to stop practising medicine

in the next 12 months, with stress or burnout (86%)

cited as the most common reason for such plans.

Burnout

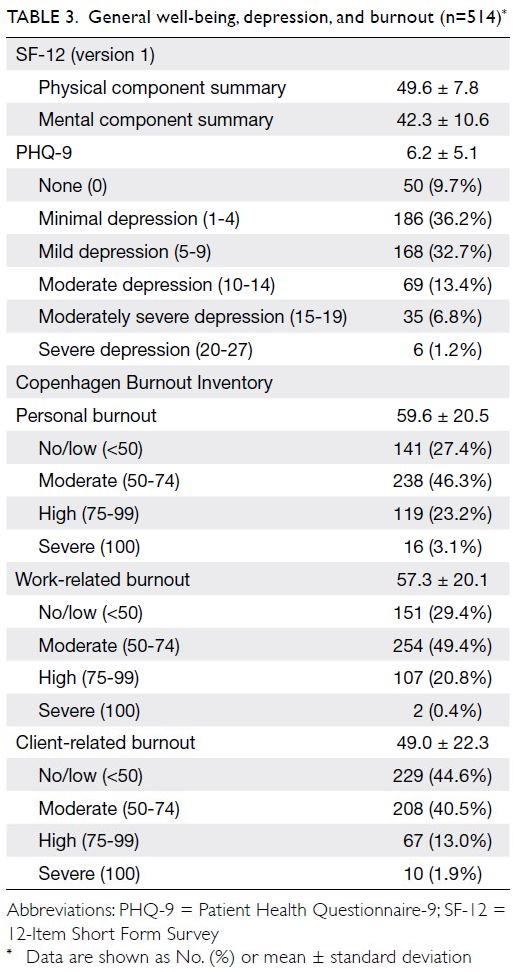

As measured by the CBI, the mean personal burnout

score was 59.6 ± 20.5, work-related burnout score

was 57.3 ± 20.1, and client-related burnout score

was 49.0 ± 22.3. Using a CBI subscale cut-off

score of ≥50 (moderate and higher), 72.6% (n=373,

95% CI=68.5%-76.4%) of respondents reported

personal burnout; 70.6% (n=363, 95% CI=66.4%-74.5%) of respondents reported work-related burnout; and 55.4% (n=285, 95% CI=51.0%-59.7%) of respondents reported client-related burnout (Table 3).

Well-being, depression, and suicidal ideation

The mean physical component summary score of the 12-Item Short Form Survey was 49.6 ± 7.8; the mean

mental component summary score of the 12-Item

Short Form Survey was 42.3 ± 10.6 (Table 3).

As measured by the PHQ-9, the mean

depression score was 6.2 ± 5.1. However, the

prevalence of depression among respondents,

defined as a score of ≥10, was 21% (n=110) [Table 3].

In total, 79% (n=404) of respondents did not report any suicidal ideation or attempt. The remaining

respondents stated that life was “not worth living”

or “wished he or she was dead”; some also reported

a history of suicidal ideation or attempts. The most

commonly cited source of stress in the past year was

clinical responsibilities/job demands.

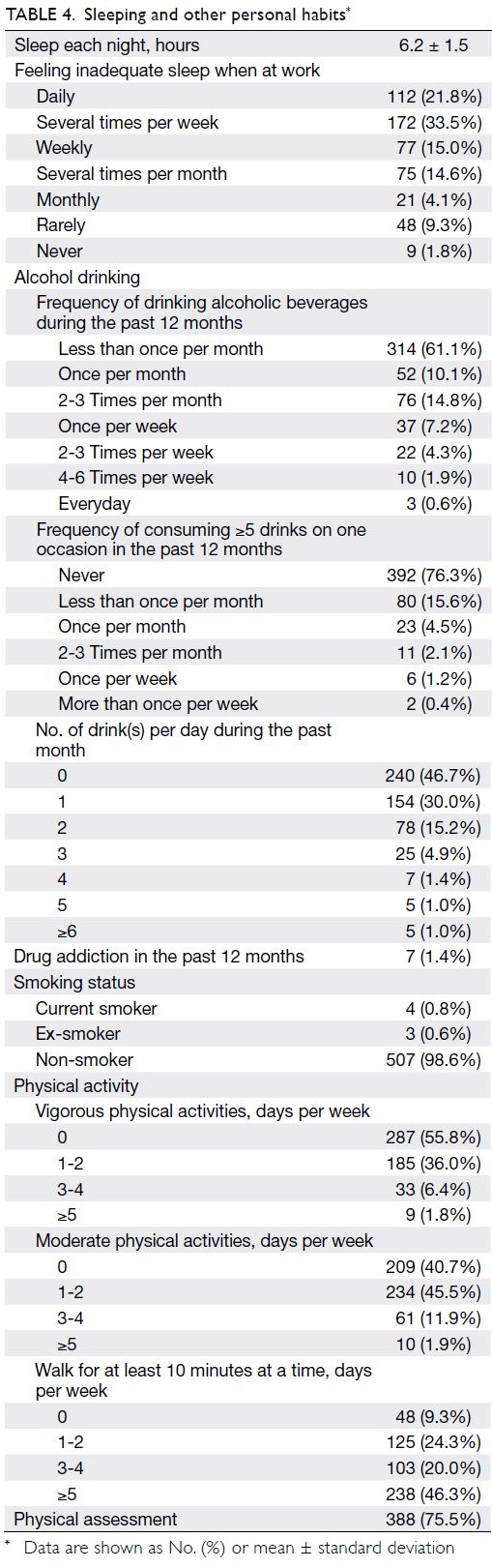

Health status

In terms of health conditions, there was a perception

among respondents that their health status was

“worse” (29%; n=148) or “much worse” (3%;

n=17) than among other individuals of the same

age. The mean duration of sleep each night was

6.2 ± 1.5 hours. However, most respondents

frequently experienced inadequate sleep when at

work; 70% (n=361) of respondents indicated that

this occurred weekly or more often. In terms of

personal habits, the prevalences of alcohol drinking,

drug addiction, and smoking were low. However, the

prevalences of regular physical activity and personal

physical assessments were not high (Table 4).

Association of factors for burnout,

depression, and suicide

Logistic regression modelling was performed to investigate bivariate associations of demographic

and professional factors with burnout, the presence

of depression, or suicide ideation and/or attempts.

The number of working hour(s) per week

(odds ratio [OR]=1.02; 95% CI=1.01-1.04; P=0.001)

was positively associated with depression (online supplementary Table 1); having children (OR=0.58;

95% CI=0.36-0.93; P=0.024) was negatively associated

with suicidal ideation/attempts. Doctors who

completed a project-based learning curriculum during

undergraduate study were less likely to be depressed

or report suicidal ideation/attempts (depression:

OR=0.60; 95% CI=0.39-0.91; P=0.017; suicidal

ideation/attempts: OR=0.65; 95% CI=0.43-1.00;

P=0.049) [online supplementary Table 2].

Older age (OR=0.97; 95% CI=0.94-0.99;

P=0.026), possession of a first university degree

in medicine or dental surgery (OR=0.37;

95% CI=0.15-0.89; P=0.027), and possession

of Academy fellowship status (OR=0.61;

95% CI=0.41-0.92; P=0.017) were associated with

lower likelihood of personal burnout. Engagement

in longer working hour(s) per week (OR=1.04;

95% CI=1.02-1.05; P<0.001) and working in Hospital

Authority clinics (OR=1.95; 95% CI=1.05-3.62;

P=0.034; compared with working in government

clinics) were positively associated with personal

burnout (online supplementary Table 3). Marital

statuses of single, separated, or divorced (OR=1.71;

95% CI=1.16-2.53; P=0.007) and engagement

in longer working hour(s) per week (OR=1.03;

95% CI=1.02-1.05; P<0.001) were positively

associated with work-related burnout (online supplementary Table 4). Conversely, having children

(OR=0.66; 95% CI=0.44-0.98; P=0.038), consultant

seniority level (OR=0.27; 95% CI=0.09-0.88; P=0.029;

compared with associate consultant seniority

level), and working in the private sector (OR=0.40;

95% CI=0.17-0.94; P=0.035; compared with working

in government) were negatively associated with work-related burnout. Provision of primary care

(OR=1.5; 95% CI=1.04-2.16; P=0.031) was associated

with client-related burnout (online supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

Main findings

This study attempted to quantify well-being and

burnout in young doctors (both resident-in-training,

and doctors within 10 years of their specialist

registration) throughout Hong Kong; there were

three main findings. First, the mean burnout score

was high in this group of doctors; mean personal

and work-related scores of ≥50 were observed on

the CBI. Second, there was a high prevalence of job

dissatisfaction (28%) in this group of doctors. Third,

the self-perceived personal well-being and mental

health were worse in this group of doctors than in

members of the general population with similar ages.

Burnout among doctors in Hong Kong and

worldwide

Burnout is a well-known occupational hazard in

people-oriented professions; doctors are at particular

risk of burnout because of their frequent engagement

in intense personal and emotional contact with

patients. Although these therapeutic and service

relationships are highly rewarding and engaging,

they can also be a source of stress. Burnout among

doctors has been recognised as a global crisis20; its

effects on personal, patient, and institutional levels

can be substantial. The expectation to meet job

demands can lead to maladaptive practices which will

ultimately compromise relationships with patients

and colleagues, with long-term consequences on

patient care.21 Hence, efforts to acknowledge that

such a problem exists represents the first step in

establishing a systematic strategy to address this

crisis.

Although there have been multiple published

reports regarding burnout among doctors, territory-wide

data focusing on junior doctors in Hong Kong are

lacking. Siu et al9 conducted a random sample survey

of 226 public doctors in 2012; they found that 31.4%

of respondents satisfied the criteria for high burnout.

Moreover, young but moderately experienced

doctors needing to work shifts were most vulnerable

to high burnout. However, the questionnaire used

in that study was not comprehensive, the random

sampling method did not produce a representative

cohort, and only public doctors were invited to

the survey. More recently, a more comprehensive

survey involving medical graduates of one university

in Hong Kong found high prevalences of personal

(63.1%) and 55.9% (work-related) burnout using the

standardised CBI.10 The more comprehensive survey represents the most comprehensive and robust study

in Hong Kong thus far, but it only included graduates

from one university in Hong Kong; it did not include

any doctors trained elsewhere.

The present study of young doctors throughout

Hong Kong found high mean personal (59.6 ± 20.5)

and work-related (57.3 ± 20.1) scores on the CBI. The

mean client-related score was 49.0 ± 22.3, slightly

below the score of 50 that constituted the threshold

for burnout. These scores were higher than in the

previous study performed in Hong Kong by Ng et al,10

which showed mean CBI scores of 57.4 ± 21.4

(personal), 48.9 ± 7.4 (work-related), and 41.5 ± 21.8

(client-related). Moreover, when compared with

studies worldwide that used the CBI to measure

burnout in doctors,15 16 18 22 the levels of burnout in the

present study were among the highest. Contributing

factors may differ among regional healthcare

systems; causes of burnout and well-being in junior

doctors may not be consistent worldwide. Our study

attempted to identify sources of stress among junior

doctors in Hong Kong; the most commonly cited

sources were clinical responsibilities/job demands

and professional examinations. Additional in-depth

studies are necessary to determine how these factors

can be modified to alleviate stress in junior doctors.

Health statuses related to burnout risk

The respondents’ general health statuses (in terms of medical conditions) were not substantially worse

than the general population, although 32% of the

respondents indicated self-perceived health worse

than their peers. The present study also showed that

the prevalence of depression was 21%, according to

the PHQ-9. This is more than double the prevalence

previously reported in Hong Kong (8.4%).23 Despite

the high prevalence of depression in the present

study, respondents indicated low rates of suicidal

ideation/attempts. Although a causal relationship

could not be established because of the observational

nature of the study, the number of working hours per

week and having children were factors that affected

risk of depression and suicidal ideation/attempts,

respectively. The mean number of hours worked per

week was 53.5 ± 14.8 hours. Junior doctors who work

>55 hours per week are reportedly twofold more

likely to have frequent health problems (OR=2.05,

95% CI=1.62-2.59; P<0.001) and suicidal ideation

(OR=2.0, 95% CI=1.42-2.82; P<0.001).24 A previous

systemic review showed an association between

long working hours and a depressive state in other

professions in general.25 Positive effects of reduced

working hours among junior doctors have been

found in some studies,26 27 but this relationship is not

consistently observed. For example, in the United

Kingdom, the Working Time Regulations were fully

applied to junior doctors beginning in 2009; these comprised a limit of 48 hours per week, averaged

across a reference period of 26 weeks, with additional

minimum rest periods. However, implementation of

the Working Time Regulations has not fully resolved

the effects of long hours and fatigue.28 Furthermore,

there are implications for professional training and

manpower planning if rigid enforcement of such

working hours is performed.

Our study did not find any substantial evidence

that young doctors were reliant on alcohol, smoking,

or drugs as coping mechanisms. This contrasts with

findings from the US, which indicated that high levels

of alcohol and substance abuse were associated with

burnout among doctors.29 It was beyond the scope

of the present study to explore other avenues that

junior doctors in Hong Kong might use to alleviate

their stress levels and burnout. Other health and

lifestyle behaviours (eg, exercise levels and personal

physical assessments) may be indicative of time

constraints related to work or personal obligations;

they may also be indicative of self-neglect caused by

such constraints and work-related burnout.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study with voluntary participation,

and the results might not be representative of all

doctors throughout public and private sectors in

Hong Kong. However, to our knowledge, this study

performed the most comprehensive survey regarding

burnout among doctors in Hong Kong thus far.

Second, the study was not designed to avoid selection

bias concerning doctors who were more prone to

burnout and therefore more interested to participate

in such surveys. Third, because the survey did not

allow free text entry in the questionnaire responses,

more in-depth analysis was not possible in some

instances. Fourth, because this was a cross-sectional

survey, no causal relationships or risk factors could

be established regarding the development of burnout

or depression. Fifth, our definition of “young” was

based on the 10 years of specialist registration, which

included doctors with various levels of experience

and responsibilities; thus, the results might not be

representative of a specific subset of doctors.

Conclusions

The present study showed that junior doctors in Hong Kong had a high level of burnout, and

there was a high prevalence of depression among

the respondents. A substantial proportion of the

respondents were dissatisfied with their present job

position. Future studies to determine causal factors

will allow the development and implementation of

specific strategies to address these problems within

Hong Kong. The maintenance of well-being in junior

doctors is vital for sustaining a healthy medical

workforce and long-term patient care.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KYH Kwan, LWY Chan, PW Cheng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KYH Kwan, LWY Chan, PW Cheng.

Drafting of the manuscript: KYH Kwan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KYH Kwan, LWY Chan, PW Cheng.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KYH Kwan, LWY Chan, PW Cheng.

Drafting of the manuscript: KYH Kwan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all members of the Young Fellows Chapter

of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine for their active

participation in this study; the secretariat and staff of the

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and its Hong Kong Jockey

Club Innovative Learning Centre for Medicine for their

administrative and information technology support; and the

Council of the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine for their

active support, encouragement, and funding of the coupons.

The authors especially thank Dicken CC Chan for statistical

assistance.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (Ref No: UW 19-062).

References

1. Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout and

depression report 2019. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed 2 Dec 2020.

2. Maslach C. What have we learned about burnout and health? Psychol Health 2001;16:607-11.Crossref

3. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. QD85 Burnout. Available from:

https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

4. Lin M, Battaglioli N, Melamed M, Mott SE, Chung AS,

Robinson DW. High prevalence of burnout among US

emergency medicine residents: results from the 2017

National Emergency Medicine Wellness Survey. Ann

Emerg Med 2019;74:682-90. Crossref

5. BeyondBlue. National Mental Health Survey of Doctors

and Medical Students 2019. Available from: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/docs/default-source/beyond-blue-s-strategic-plan-2020-2023/research-project-files/bl1132-report---nmhdmss-full-report_web.pdf?sfvrsn=845cb8e9_14. Accessed 3 Dec 2020.

6. Bhugra D, Sauerteig SO, Bland D, et al. A descriptive study

of mental health and wellbeing of doctors and medical

students in the UK. Int Rev Psychiatry 2019;31:563-8. Crossref

7. Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, et al. Prevalence of burnout and

associated factors among general practitioners in Hubei,

China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1607. Crossref

8. Huang EC, Pu C, Huang N, Chou YJ. Resident burnout in Taiwan Hospitals—and its relation to physician felt trust from patients. J Formos Med Assoc 2019;118:1438-49. Crossref

9. Siu CF, Yuen SK, Cheung A. Burnout among public doctors in Hong Kong: cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:186-92.

10. Ng AP, Chin WY, Wan EY, Chen J, Lau CS. Prevalence and severity of burnout in Hong Kong doctors up to 20

years post-graduation: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open

2020;10:e040178. Crossref

11. Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB.

The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: a new tool for the

assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005;19:192-207. Crossref

12. Rizzo R, Piccinelli M, Mazzi MA, Bellantuono C, Tansella M.

The Personal Health Questionnaire: a new screening

instrument for detection of ICD-10 depressive disorders in

primary care. Psychol Med 2000;30:831-40. Crossref

13. Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Vänskä J, et al. Health,

psychosocial factors and retirement intentions among

Finnish physicians. Occup Med (Lond) 2008;58:406-12. Crossref

14. Taylor K, Lambert T, Goldacre M. Future career plans of

a cohort of senior doctors working in the National Health

Service. J R Soc Med 2008;101:182-90. Crossref

15. Benson S, Sammour T, Neuhaus SJ, Findlay B, Hill AG. Burnout in Australasian younger fellows. ANZ J Surg

2009;79:590-7. Crossref

16. Chou LP, Li CY, Hu SC. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004185. Crossref

17. Creedy DK, Sidebotham M, Gamble J, Pallant J, Fenwick J.

Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress

in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC

Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:13. Crossref

18. Wright JG, Khetani N, Stephens D. Burnout among faculty

physicians in an academic health science centre. Paediatr Child Health 2011;16:409-13. Crossref

19. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-13. Crossref

20. Physician burnout: a global crisis [editorial]. Lancet 2019;394:93. Crossref

21. Graham J, Potts HW, Ramirez AJ. Stress and burnout in doctors. Lancet 2002;360:1975-6. Crossref

22. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being.

JAMA 2018;319:1541-2. Crossref

23. Cheng CM, Cheng M. To validate the Chinese version of

the 2Q and PHQ-9 questionnaires in Hong Kong Chinese

patients. HK Pract 2007;29:381-90.

24. Petrie K, Crawford J, LaMontagne AD, et al. Working

hours, common mental disorder and suicidal ideation

among junior doctors in Australia: a cross-sectional survey.

BMJ Open 2020;10:e033525. Crossref

25. Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between

long working hours and health: a systematic review of

epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health

2014;40:5-18. Crossref

26. Kiernan M, Civetta J, Bartus C, Walsh S. 24 Hours on-call

and acute fatigue no longer worsen resident mood under

the 80-hour work week regulations. Curr Surg 2006;63:237-41. Crossref

27. Kort KC, Pavone LA, Jensen E, Haque E, Newman N,

Kittur D. Resident perceptions of the impact of work-hour

restrictions on health care delivery and surgical education:

time for transformational change. Surgery 2004;136:861-71. Crossref

28. Morrow G, Burford B, Carter M, Illing J. Have restricted

working hours reduced junior doctors' experience of

fatigue? A focus group and telephone interview study. BMJ

Open 2014;4:e004222. Crossref

29. Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The

prevalence of substance use disorders in American

physicians. Am J Addict 2015;24:30-8. Crossref