Health behaviour practices and expectations for a local cancer survivorship programme: a crosssectional study of survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Med J 2022 Feb;28(1):33–44 | Epub 25 Jan 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Health behaviour practices and expectations for

a local cancer survivorship programme: a cross-sectional study of survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong

YT Cheung, PhD1; LS Yang, BPharm, MCP1; Justin CT Ma, HBSc1; Patricia HK Woo, BPharm1; Sammy MS Luk, BPharm1; Thomas CH Chan, BPharm1; Vivian WY Lee, DPharm2; Nelson CY Yeung, PhD3; CK Li, MB, BS, MD4

1 School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Centre for Learning Enhancement and Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital

Corresponding author: Prof YT Cheung (yinting.cheung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Lifestyle choices may influence health

outcomes in cancer survivors. This study of childhood

cancer survivors in Hong Kong investigated factors

associated with health-protective and health-damaging

behaviours; it also examined expectations

of a survivorship programme.

Methods: This cross-sectional study recruited

survivors of childhood cancer ≥2 years after treatment.

Survivors completed a structured questionnaire to

report their health practices and the perceived values of

survivorship programme components. Multivariable

logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify

factors associated with health behaviours.

Results: Two hundred survivors were recruited

(mean age=23.4 ± 8.8 years; mean duration since

treatment, 13.4 ± 7.6 years). Comparatively few

survivors exercised ≥4 days/week (16.0%), used sun

protection (18.0%), and had a balanced diet (38.5%).

Furthermore, comparatively few survivors reported

that they had not undergone any immunisation (24.5%)

or were unsure (18.5%) about their immunisation

history. Most adult survivors were never-drinkers

(71.0%) and never-smokers (93.0%). Brain tumour

survivors were more likely to have unhealthy eating

habits, compared with haematological malignancy

survivors (odds ratio [OR]=2.45; 95% confidence

interval [CI]=1.29-4.68). Lower socioeconomic

status was associated with inadequate sun protection

(OR=0.20; 95% CI=0.05-0.83), smoking (OR=5.13; 95% CI=1.48-17.75), and exposure to second-hand

smoke (OR=3.52; 95% CI=1.42-8.69). Late-effects

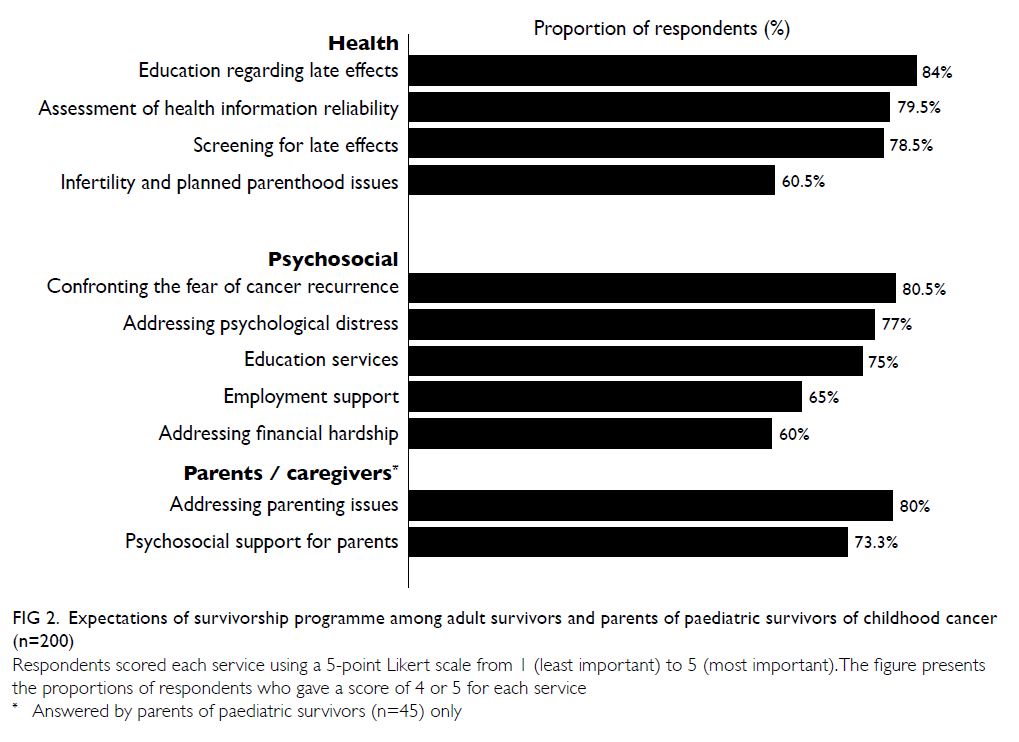

screening (78.5%) and psychosocial services to

address psychological distress (77%) were considered

essential components of a survivorship programme.

Conclusions: Despite the low prevalences of health-damaging

behaviours, local survivors of childhood

cancer are not engaging in health-protective behaviours.

A multidisciplinary programme addressing late effects

and psychosocial aspects may address the multifaceted

needs of this special population.

New knowledge added by this study

- Despite the low prevalences of health-damaging behaviours, engagement in health-protective behaviours among survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong was unsatisfactory, particularly with regard to participation in regular physical activity, consumption of a balanced diet, and the use of sun protection.

- Indicators of lower socioeconomic status (ie, lower education attainment and monthly household income) were collectively identified as predictors of smoking, poor dietary habits, and lack of immunisation.

- Survivors of childhood cancer regarded services concerning health issues (eg, education and screening for late effects) as the most important aspects of survivorship care. They also preferred enrolment into a survivorship programme early in the cancer care continuum.

- A potential intervention opportunity may involve engaging survivors and families in a structured comprehensive survivorship programme during their transition to survivorship. The centralisation of paediatric oncology services in the new Hong Kong Children’s Hospital has provided an unprecedented opportunity for oncologists and allied health professionals to initiate a formal paediatric cancer survivorship programme that is tailored to the healthcare system in Hong Kong.

- A multidisciplinary and interactive programme addressing late effects and psychosocial aspects may help survivors of childhood cancer take age-appropriate ownership of their health and function as active partners with their health providers during the survivorship phase.

- Underserved survivors may require special navigation services and care coordination to promote adherence to surveillance, preventive care, and health-protective behaviours.

Introduction

Advancements in diagnostic and treatment strategies

have led to substantial improvements in treatment

prognoses for children with cancer. The 5-year

survival rate of childhood cancers has increased

dramatically in high-resource settings, from <50% in

the 1970s to >80% in the past decade.1 Consequently,

there has been a global surge in the population

of survivors of childhood cancer, especially in

developed regions such as Hong Kong. According to

the Hospital Authority Cancer Registry, from 2001

to 2017 in Hong Kong, approximately 180 paediatric

patients <19 years of age were diagnosed with

cancer each year.2 It is unquestionably necessary to

further improve survival rates, and recent efforts

and resources have been dedicated to improving the

quality of life and health outcomes of survivors of

childhood cancer in Hong Kong.3 4 5

Cancer survivors are susceptible to developing

a spectrum of late effects because of their previous

treatment exposures.6 7 Studies have shown that

histories of specific treatment exposures, coupled

with continued engagement in health-damaging behaviours during survivorship, may accelerate or

exacerbate the development of late effects.8 9 The

Children’s Oncology Group (COG)10 provide details

of common health-damaging behaviours and their

potential impacts on various treatment-related

chronic conditions.

Adult and paediatric oncology research has

suggested that cancer survivors and their families

are often highly receptive to education regarding

optimal lifestyles during the early survivorship

period.11 Thus, the COG and other international

oncology groups have specified that an ideal

cancer survivorship programme should comprise

recommended screening/surveillance protocols to

detect recurrence and late effects, health promotion

activities, specialty referrals, and psychosocial

interventions.7 12 One systematic review reported

that a comprehensive cancer survivorship care

programme is associated with positive behavioural

change and better health outcomes in survivors.3

In Hong Kong, a recent study by Chan et al13

showed that, although the rates of smoking and

alcohol consumption were low among local

survivors of childhood cancer, survivors were less

likely than their healthy siblings to participate

in cancer screening. However, the study did not

examine frequencies of engagement in other

health-protective behaviours, such as participation

in physical activity, undergoing immunisation,

using sunscreen, and consuming a balanced

diet. Furthermore, survivors’ expectations of a

comprehensive survivorship programme have not

been investigated. The identification of predictors

of poor health-behaviour practices and elucidation

of survivors’ needs will presumably assist clinicians

in developing targeted interventions to address the

needs of this special population.

The primary aim of this study was to identify

factors associated with engagement in health-protective

and health-damaging behaviours among

local survivors of childhood cancer. The secondary

aim was to examine cancer survivors’ expectations

of a comprehensive survivorship programme in

Hong Kong.

Methods

Study design and population

This prospective, observational study was conducted

at the paediatric oncology/haematology long-term

follow-up clinic of the Prince of Wales Hospital,

Hong Kong. Eligible participants were recruited

through convenience sampling. Between June 2019

and March 2020, the study investigators obtained

the list of patients who were scheduled to attend

follow-up consultations at the long-term follow-up

clinic; this clinic was typically held once per week.

Patients were then screened for eligibility using the in-house electronic patient record system (Clinical

Management System). All eligible patients who

subsequently attended the long-term follow-up

clinic were invited to participate in the study.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis

with primary cancer before 18 years of age; treatment

in any medical institutions in Hong Kong; survival

for at least 2 years since the completion of cancer

treatment or 5 years since diagnosis; and ability to

communicate in Cantonese. A parent was recruited

if the survivor was aged ≤16 years, or if the survivor

was cognitively impaired. Patients were excluded if

they were diagnosed with non-cancer conditions (eg,

aplastic anaemia, thalassemia), did not understand

Cantonese, were still on active treatment, or had

incomplete treatment data.

Data collection

Clinical data regarding cancer diagnosis, treatment

history, commodities, and relapse status were

retrieved from survivors’ electronic health records. A

20-minute structured questionnaire was interviewer-administered.

Participants self-reported their

socioeconomic information (ie, highest education

attainment, medical insurance, and monthly family

income).

Health behaviours were measured using a

version of the 2013 National Youth Risk Behaviour

Survey14 that had been modified and translated into

Traditional Chinese. To adapt the survey for use

within the study population, questions pertaining

to the healthy behaviour practices of young adult

cancer survivors were added. These additional

questions were developed based on the health

behaviours and practices most frequently reported

in studies of survivors of childhood cancer in other

countries.9 15 16 Health-protective behaviours refer to

engagement in physical activity, balanced diet, sun

protection, and immunisation programmes. Health-damaging

practices refer to alcohol consumption,

smoking, and exposure to second-hand smoke.

Alcohol consumption and smoking practices were

evaluated in adult survivors only, as the legal age

for purchasing tobacco and alcoholic products is

18 years in Hong Kong.

Participants were asked to rate the perceived

values of recommended components of a

comprehensive survivorship programme12 in the

categories of health, psychosocial, parenting, and

financial issues. Ratings were conducted using a

5-point Likert scale (1=least important, 5=most

important). Participants were also asked to report

their preferred time of enrolment into a survivorship

programme and modes of services.

Sample size

The current analysis is part of a broader study17 that aimed to evaluate the effect of an educational intervention on improving awareness of personal

health risks among survivors (primary outcome), as

well as general health literacy and health behaviours

among survivors (auxiliary outcomes). The tailored

educational intervention included a review of

the survivor’s cancer treatment summary and

teaching materials that contained simplified health

promotion messages derived from the COG Health

Links.10 Sample size was determined based on the

primary outcome (awareness of personal health

risks). A similar study by Landier et al18 showed that

the proportion of survivors of childhood cancer who

adequately understood their health risks (defined as

awareness of >75% of treatment-related late effects

for which they were at risk) was approximately

55% after two sessions of the tailored intervention

(ie, θ=0.55). At α=0.05, the required sample size

for achieving 80% power to detect a difference in

proportion (target θ0=0.45) between pre- and post-intervention

assessments was 195. The current

analysis reported the health behavioural practices of

participants who provided baseline, pre-intervention

assessments.

Statistical analysis

The SAS University Edition (version 2015; SAS

Institute Inc, Cary [NC], US) software was used for

all statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were

used to summarise participants’ demographics,

clinical characteristics, and frequencies of health

behaviours. Multivariable logistic regression

analysis was conducted to identify factors that were

associated with health behaviours. Associations

were presented using odds ratios (ORs) and 95%

confidence intervals (95% CIs). Based on a literature

review,9 15 19 20 the hypothesised predictors comprised

demographics and clinical characteristics (sex,

age, cancer diagnosis, and time since diagnosis), as

well as socioeconomic status (medical insurance

status, monthly household income, and highest

education attainment [in adult survivors only]).

Finally, descriptive statistics were used to summarise

participants’ preferences for the components of a

comprehensive survivorship programme.

Results

Participant characteristics

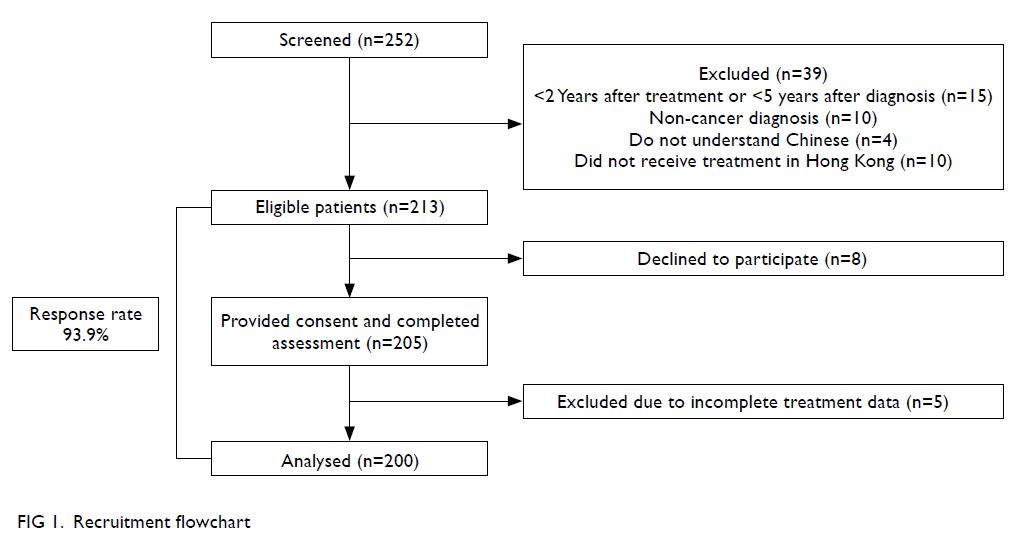

In total, 252 survivors were screened for eligibility;

39 were excluded for <2 years since treatment or <5

years since diagnosis, the presence of non-cancer

diagnoses (eg, benign ovarian teratoma), inability

to understand Chinese, or treatment performed

outside of Hong Kong. Subsequently, 213 eligible

participants were approached. Eight survivors

declined to participate, while the remaining 205

eligible survivors provided informed consent

and completed the study. Five participants were subsequently excluded because of incomplete

treatment records. Finally, data from 200 participants

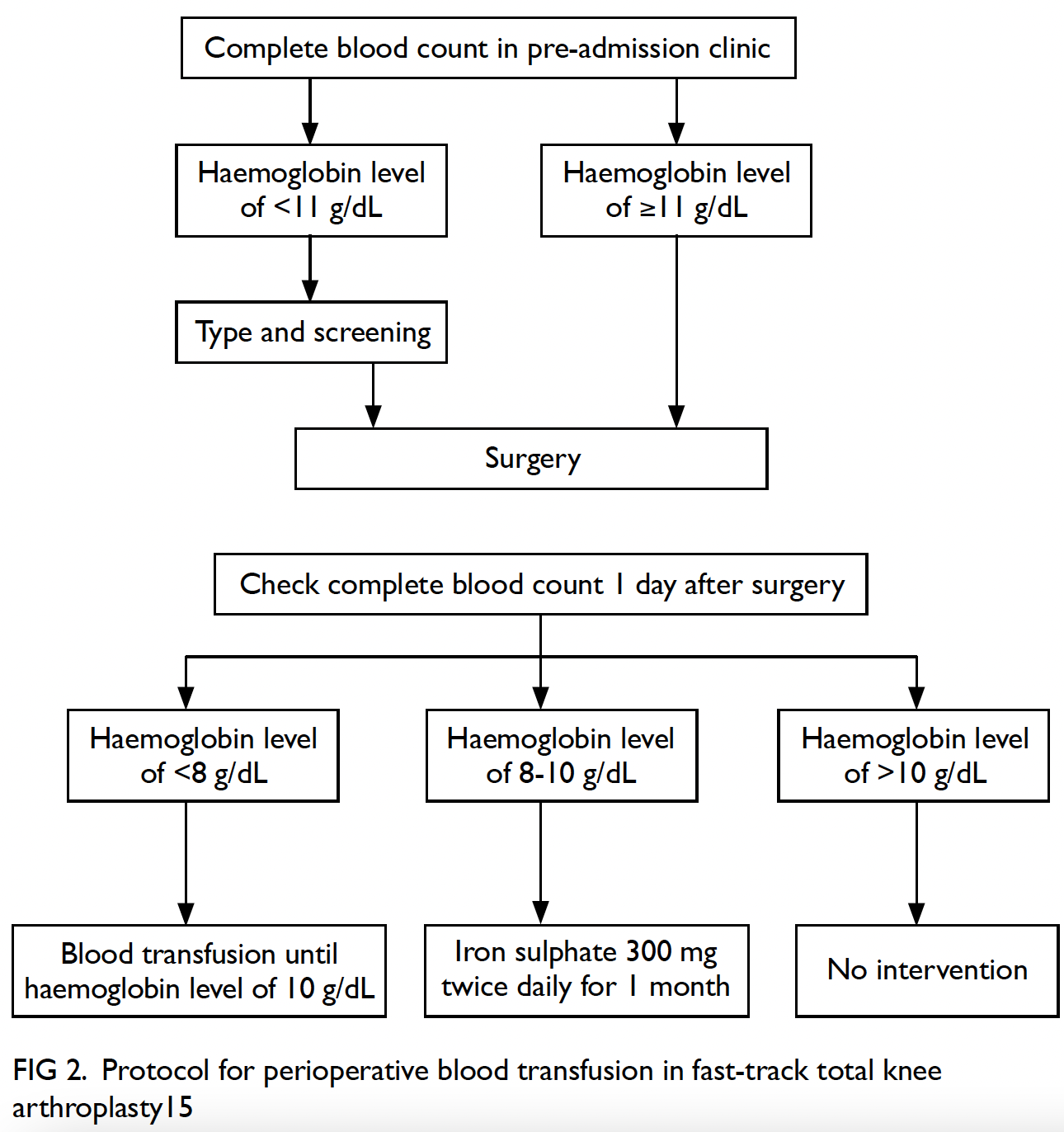

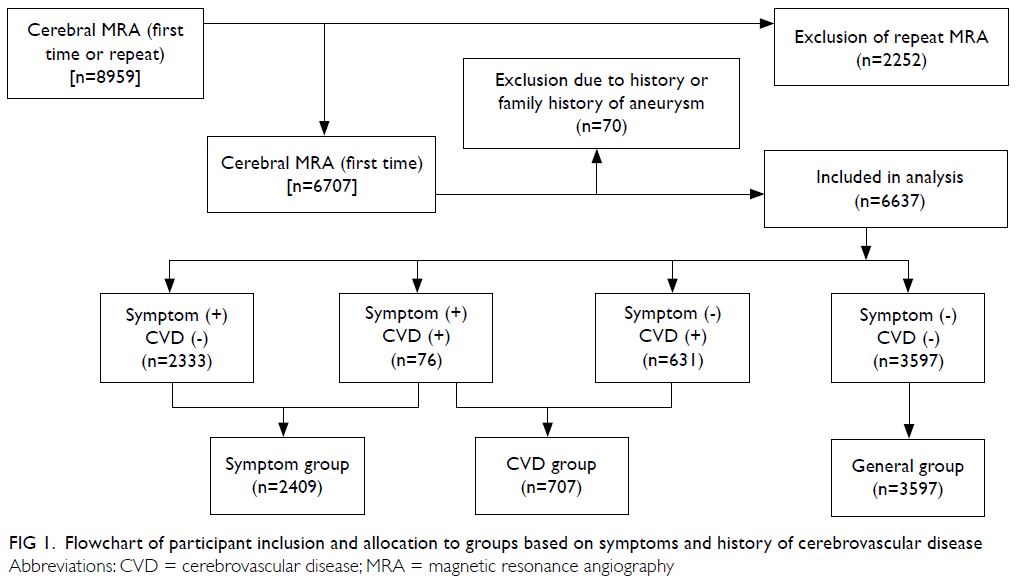

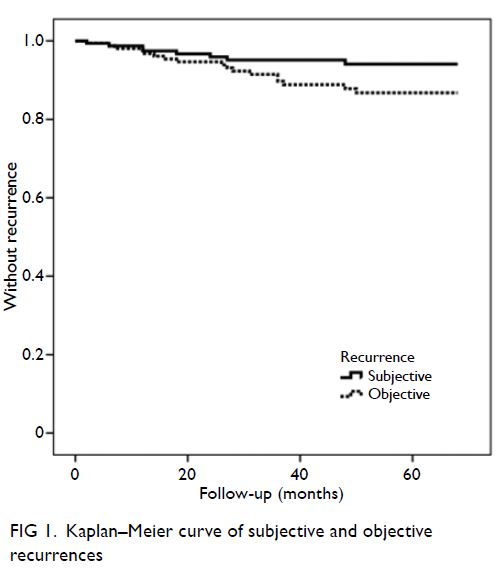

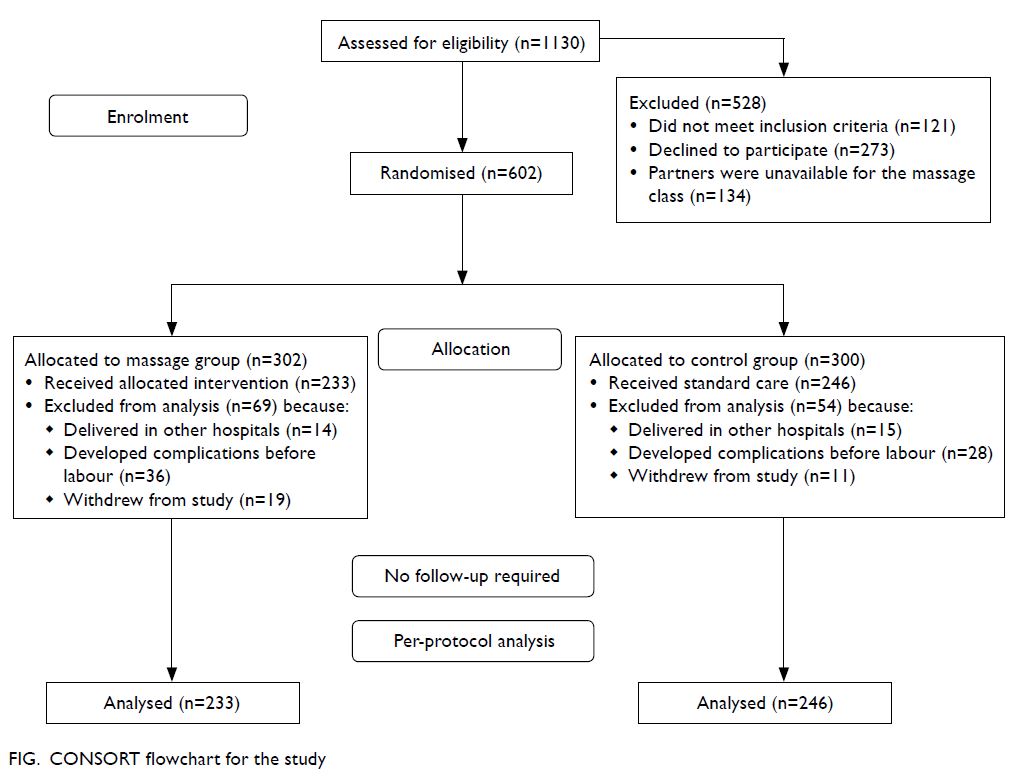

were analysed (response rate 93.9%) [Fig 1].

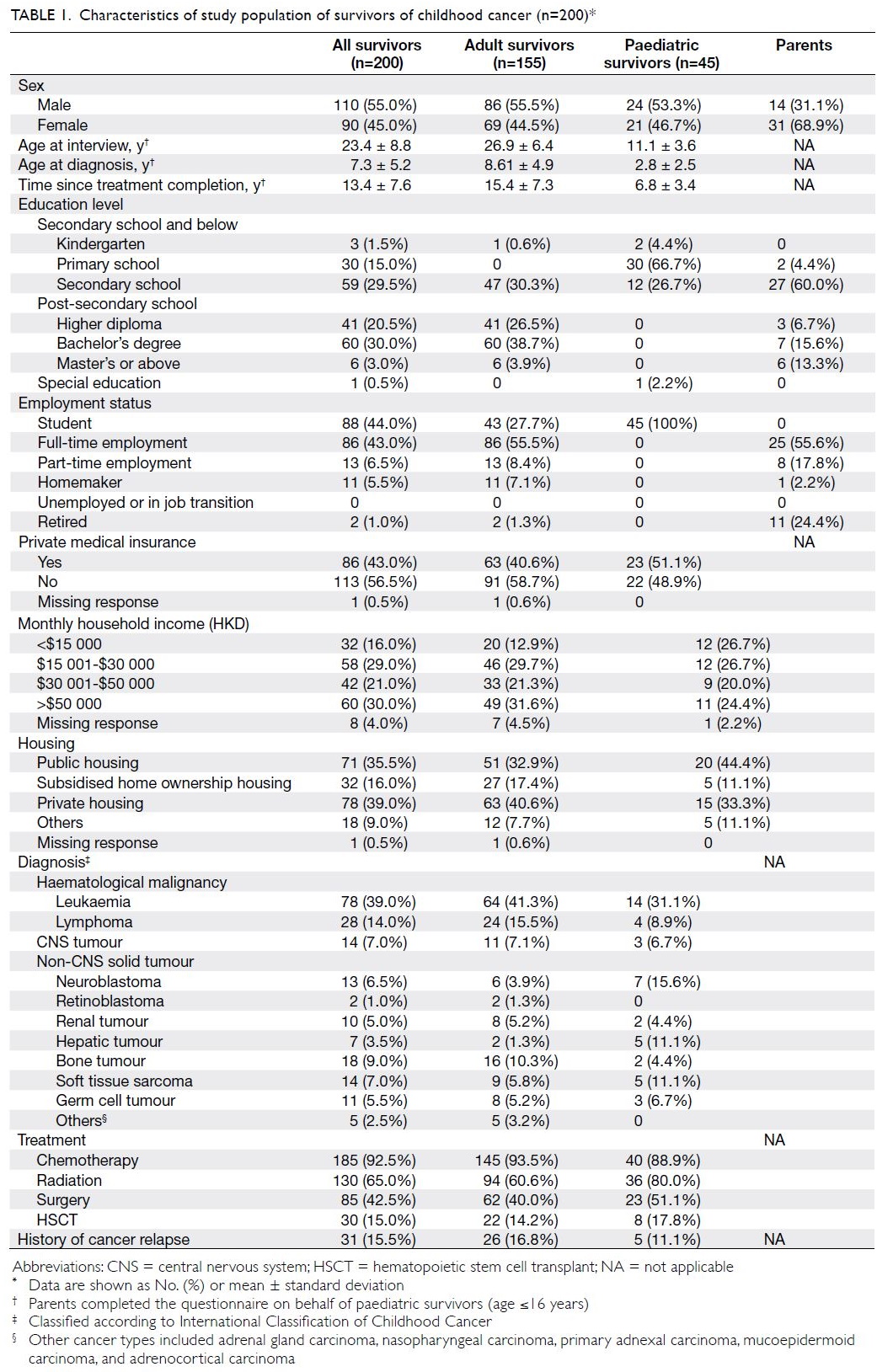

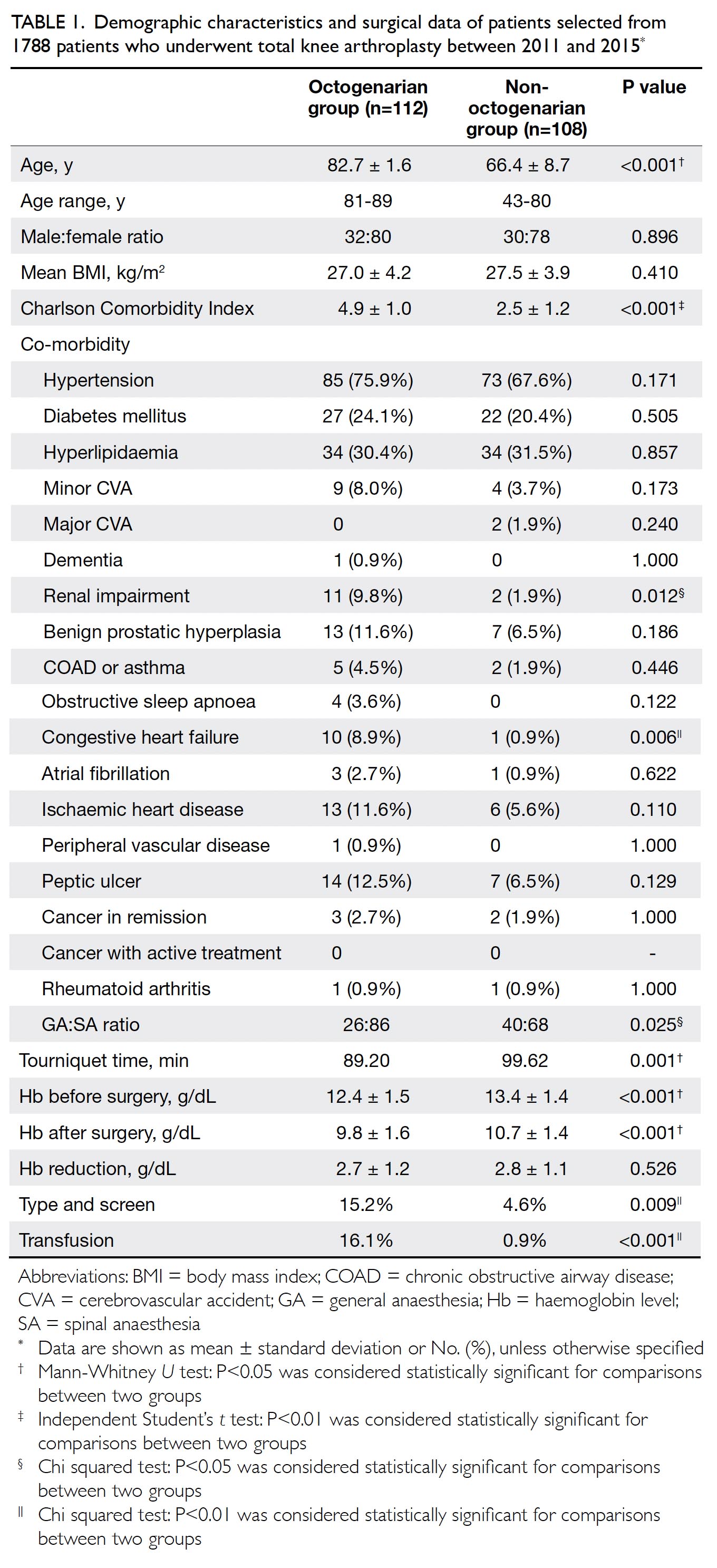

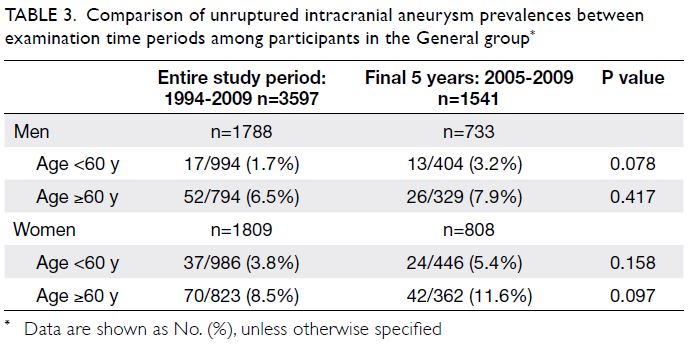

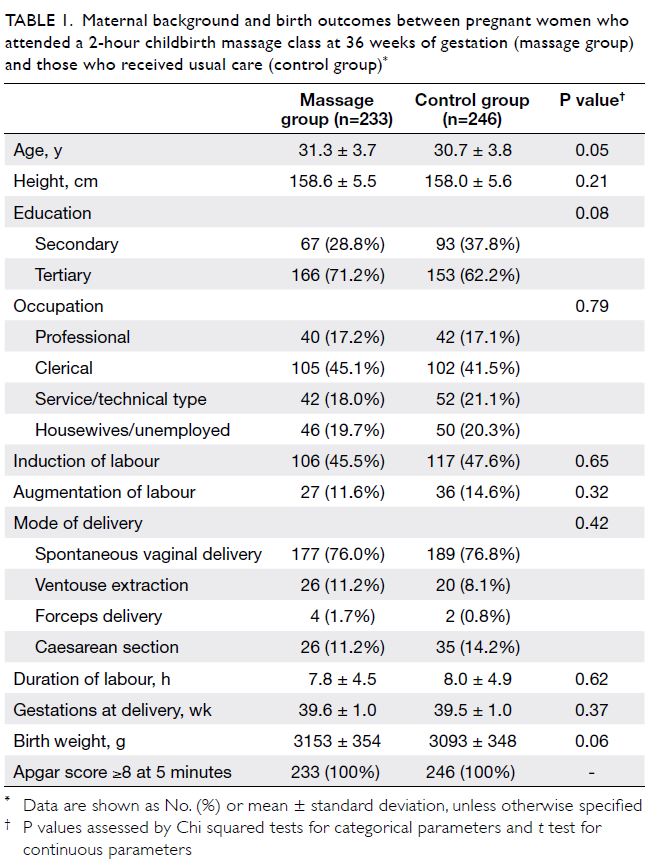

The mean (± standard deviation) ages at

interview were 26.9 ± 6.4 years and 11.1 ± 3.6 years

among adult and paediatric survivors, respectively

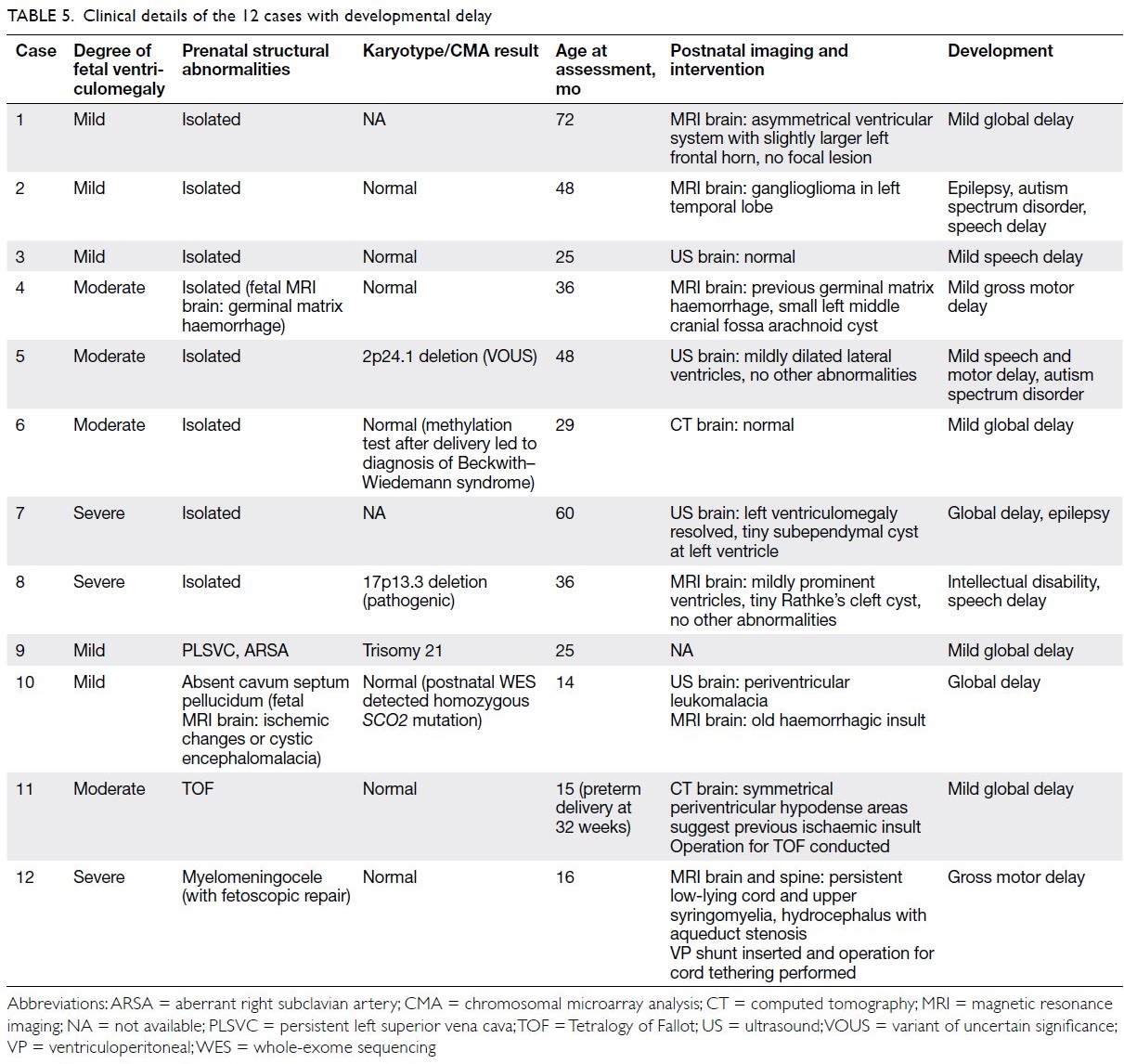

(Table 1). The mean age at cancer diagnosis was

7.3 ± 5.2 years. The mean time since treatment

completion was 13.4 ± 7.6 years; 41.0% (n=82) of

survivors were within 10 years after treatment. The

most common diagnoses were leukaemia (n=78,

39.0%), lymphoma (n=28, 14.0%), and bone tumour

(n=18, 9.0%). In total, 185 survivors (92.5%) had

undergone chemotherapy, 130 survivors (65.0%)

had received radiation, and 85 survivors (42.5%)

had undergone surgery. Only 30 survivors

(15.0%) had received hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation.

All paediatric survivors were students. Among

adult survivors, 107 (69.0%) had completed post-secondary

education. Only 32 survivors (16.0%)

reported a monthly household income of less than

HKD$15 000, and 86 survivors (43.0%) had private

medical insurance.

Interviews for paediatric survivors (n=45)

were completed by parents (Table 1). The mean

age of parents was 43.4 ± 7.7 years, and 43 (95.6%)

parents had completed secondary school or higher

education.

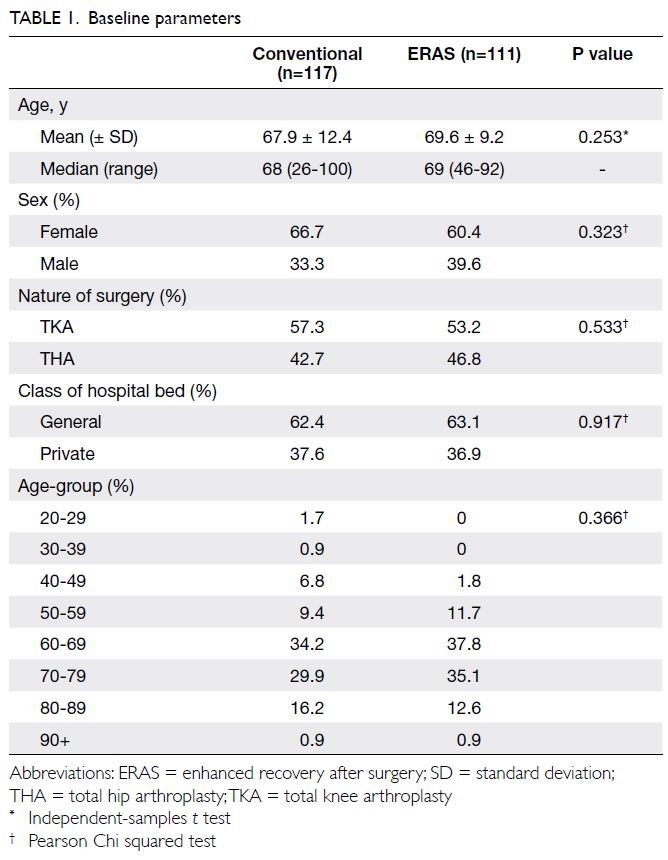

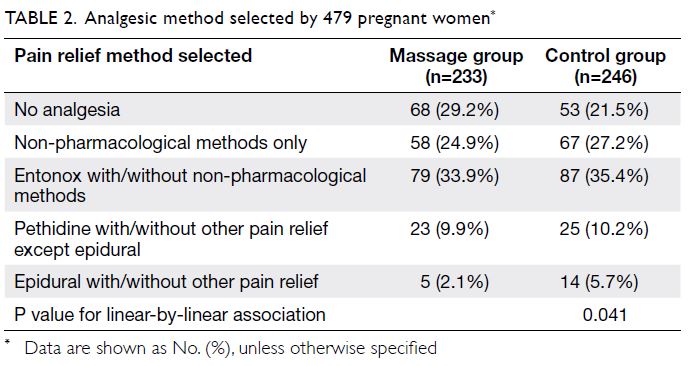

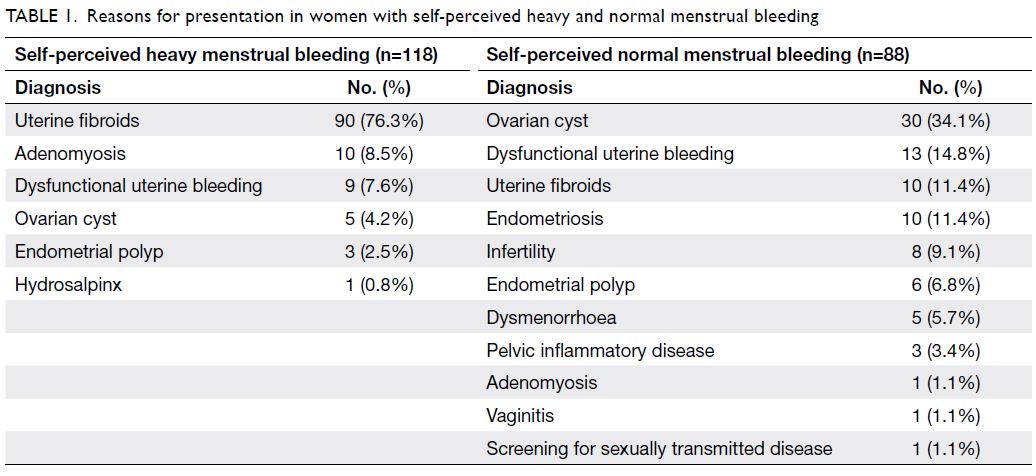

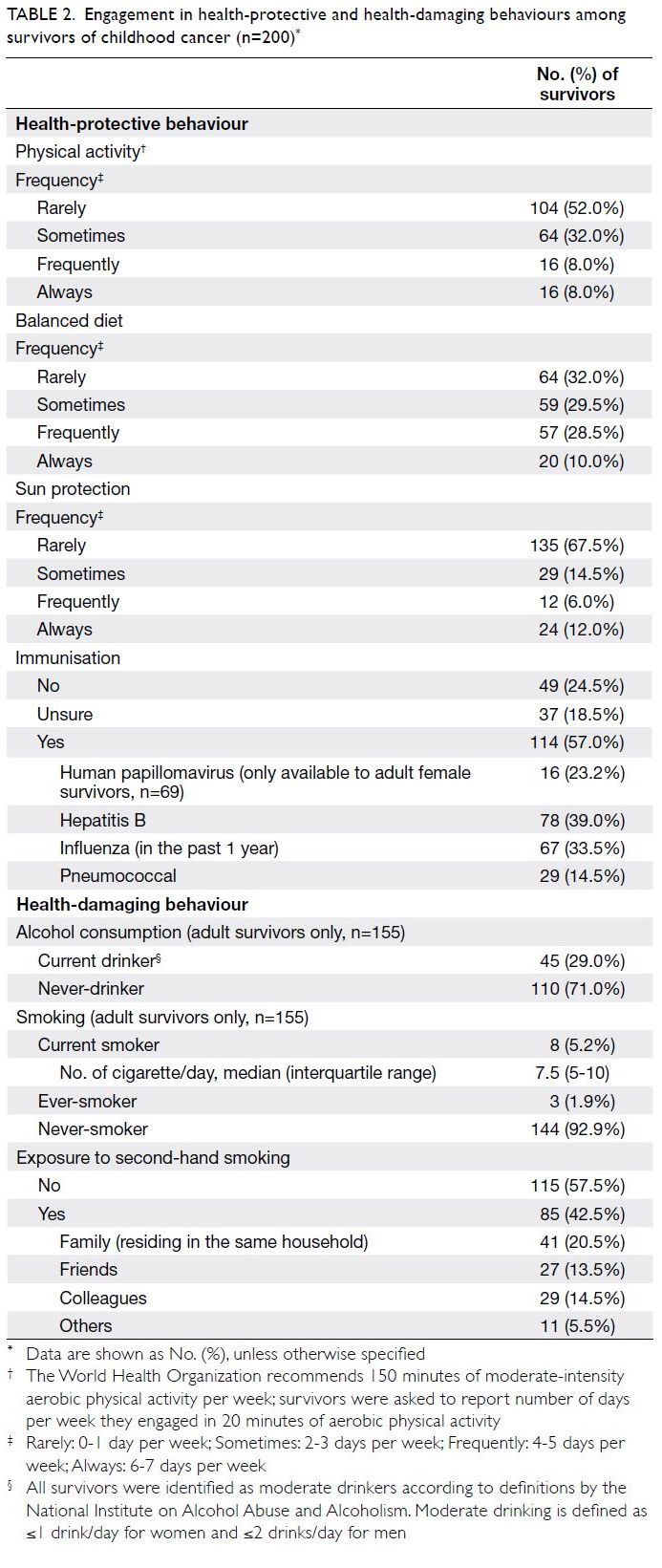

Health behaviour practices

The health-protective and health-damaging

behaviours of survivors are summarised in

Table 2. The least frequently practised health-protective health-protective

behaviour was physical activity. Only

16 survivors (8%) met the World Health Organisation

recommendation of engagement in 20 minutes

of aerobic physical activity for ≥4 days per week.

Of the survivors, 104 (52.0%) reported that they

exercised rarely (≤1 day per week) and 135 (67.5%)

applied sunscreen rarely. Fewer than 40% of

survivors “always” and “frequently” had a balanced

diet. In terms of immunisation practice, 49 (24.5%)

survivors reported that they did not undergo any

immunisation and 37 (18.5%) were unsure about

their immunisation history.

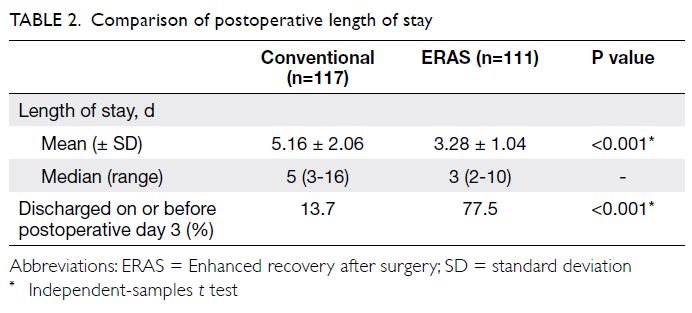

Table 2. Engagement in health-protective and health-damaging behaviours among survivors of childhood cancer (n=200)

Among 155 adult survivors, 110 (71.0%)

were never-drinkers, whereas 45 (29.0%) identified

themselves as social drinkers. These social drinkers

met the “moderate” and “low-risk” drinker

definitions established by the National Institute on

Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.21 Of the 155 adult

survivors, 144 (92.9%) were never-smokers and three

(1.9%) were ever-smokers. Only eight survivors

(5.2%) were current smokers; they smoked a median

of 7.5 cigarettes per day (interquartile range=5-10).

Of the survivors, 85 (42.5%) were exposed to second-hand

smoke; 41 (20.5%) from family members and

29 (14.5%) from colleagues.

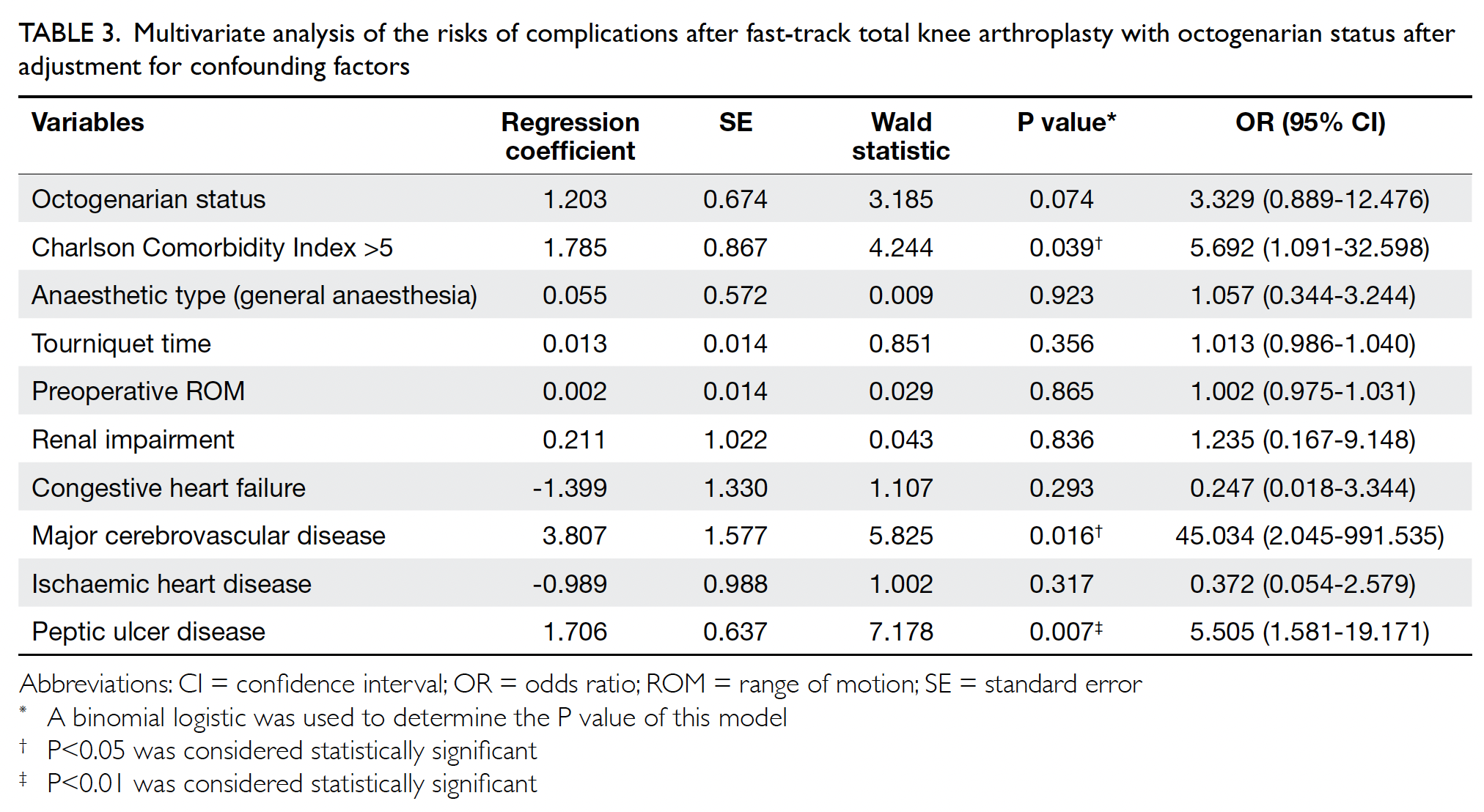

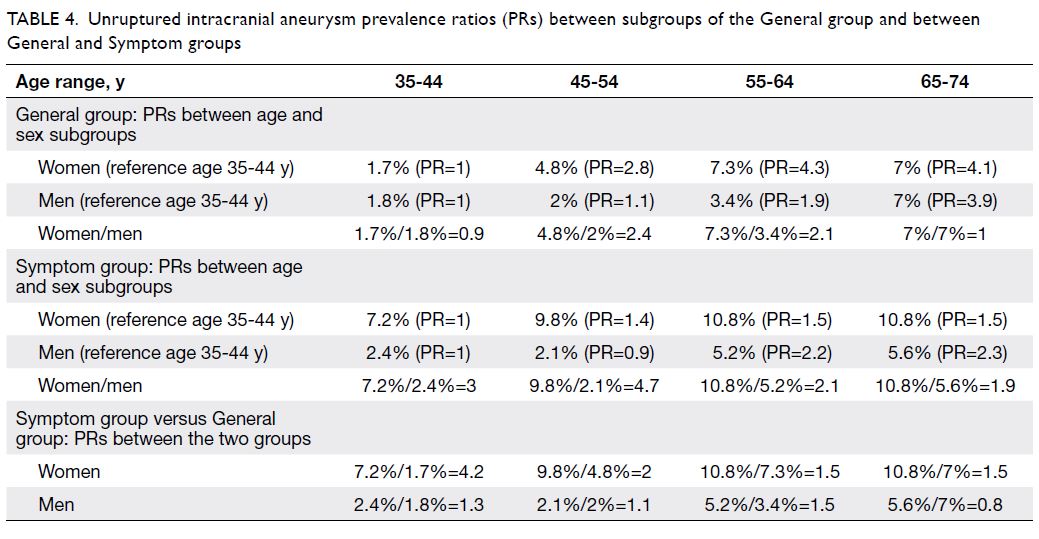

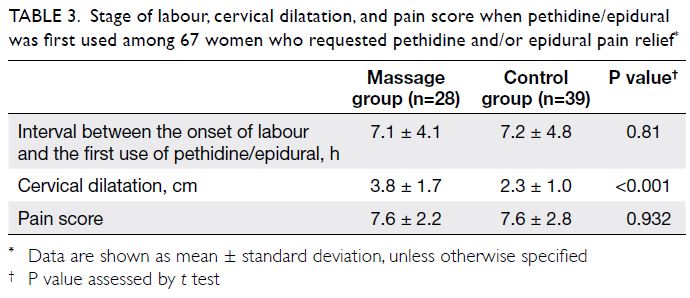

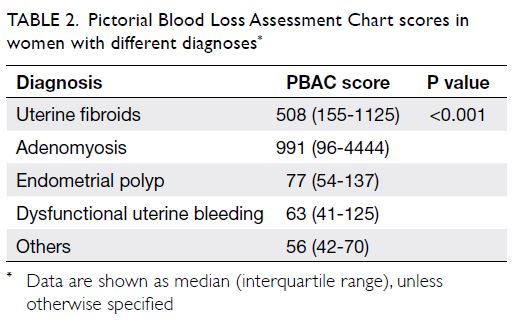

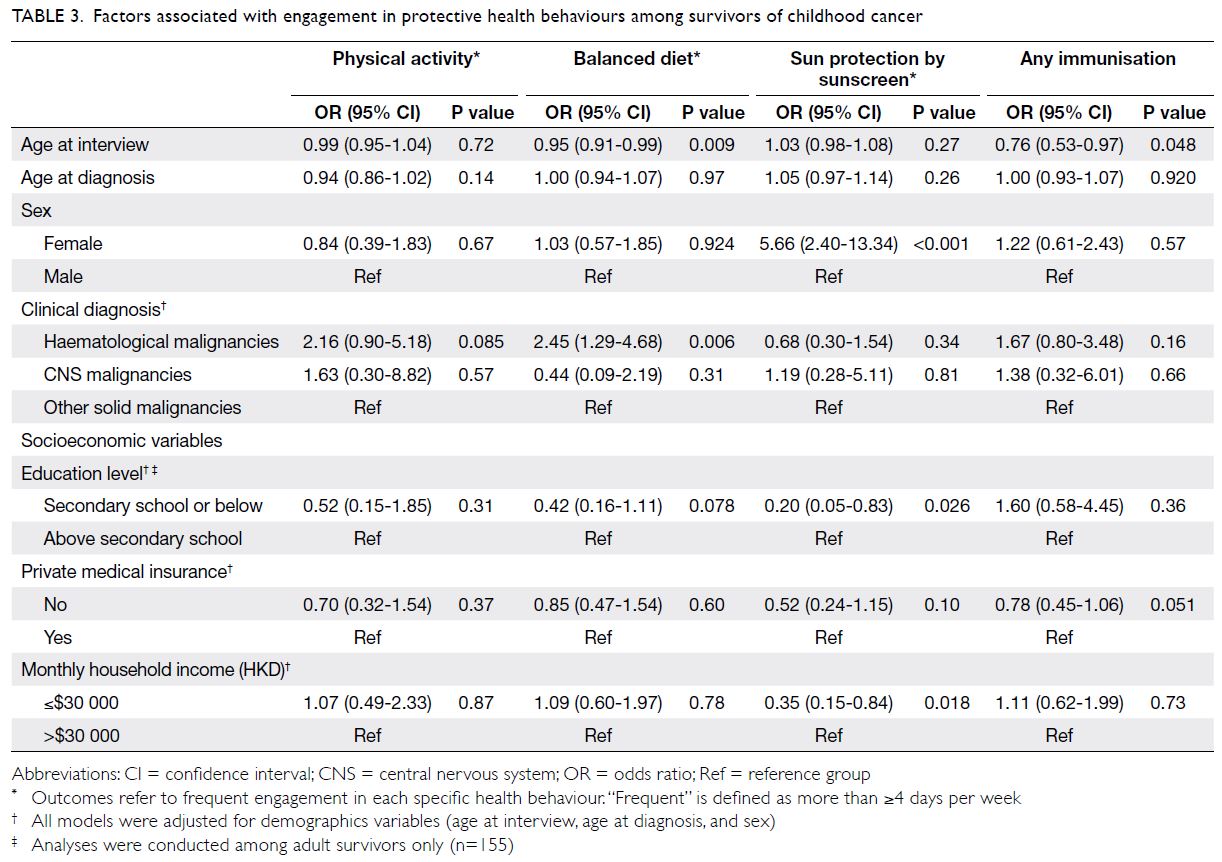

Factors associated with health behaviours

Compared with survivors of central nervous system

(CNS) tumours, survivors who had been diagnosed

with haematological malignancies were more likely to

adopt a balanced diet (OR=2.45; 95% CI=1.29-4.68).

Younger age at interview was also a significant

predictor of adoption of a balanced diet (OR=0.95;

95% CI=0.91-0.99) [Table 3].

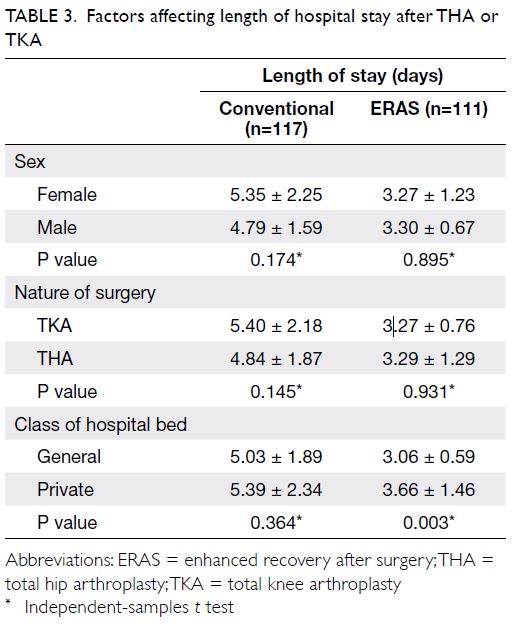

Table 3. Factors associated with engagement in protective health behaviours among survivors of childhood cancer

Female survivors had more than fivefold

greater odds of regular sunscreen use, compared

with male survivors (OR=5.66; 95% CI=2.40-13.34).

Lower education level in adult survivors (OR=0.20;

95% CI=0.05-0.83) and lower monthly household

income (OR=0.35; 95% CI=0.15-0.84) were

associated with inadequate sun protection (Table 3).

Older survivors were less likely than younger

survivors to participate in immunisation programmes

(OR=0.76; 95% CI=0.53-0.97). Although the

difference was not statistically significant (P=0.051),

immunisation practices tended to be less common in

survivors who did not have private medical insurance,

compared with survivors who did (OR=0.78;

95% CI=0.45-1.06).

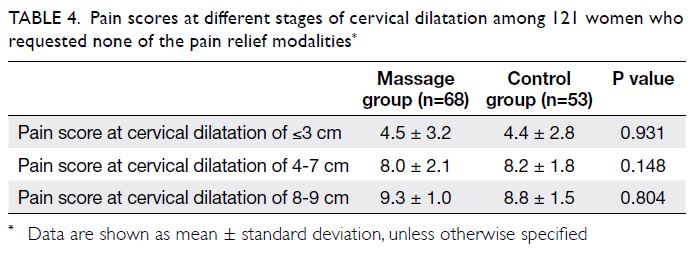

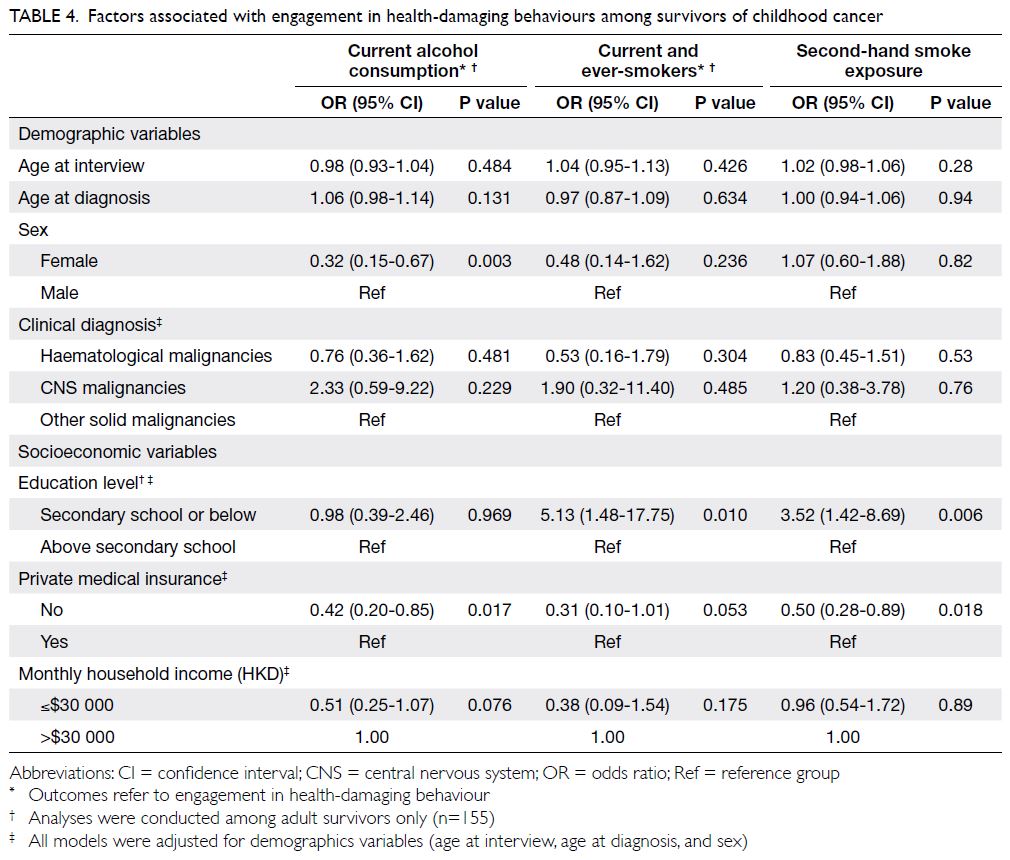

In terms of health-damaging behaviours

(Table 4), compared with survivors who had

completed education to a higher level than secondary

school, adult survivors with a lower education level

had greater odds of being current or ever-smokers

(OR=5.13; 95% CI=1.48-17.75) and of being exposed

to second-hand smoke (OR=3.52; 95% CI=1.42-8.69).

Table 4. Factors associated with engagement in health-damaging behaviours among survivors of childhood cancer

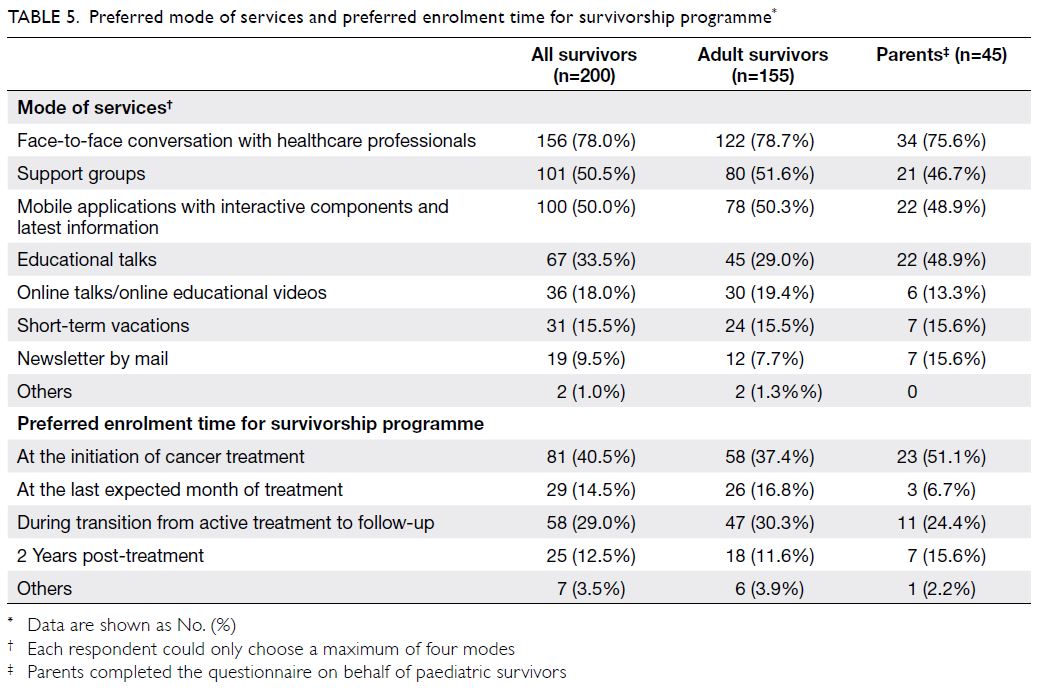

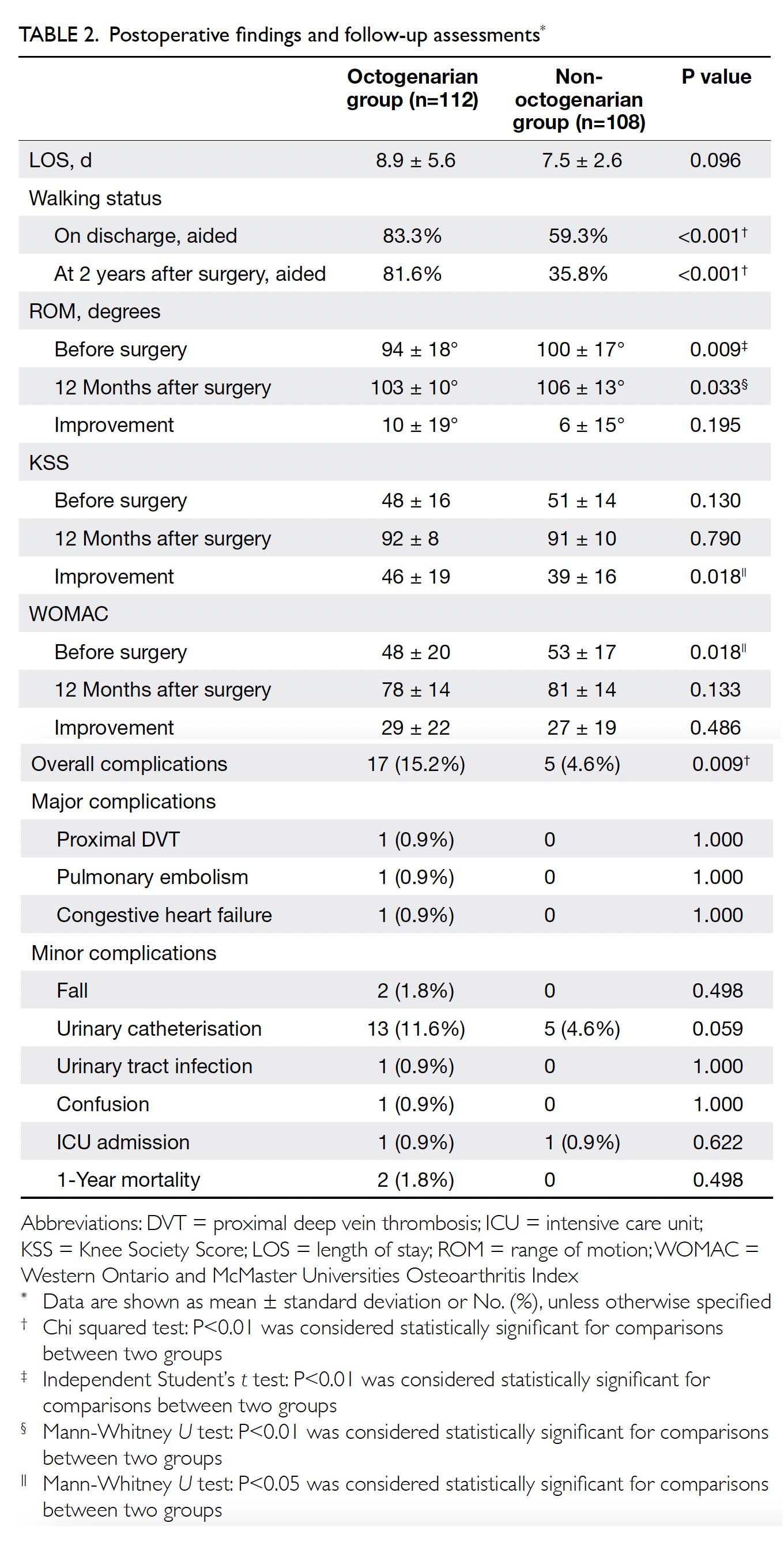

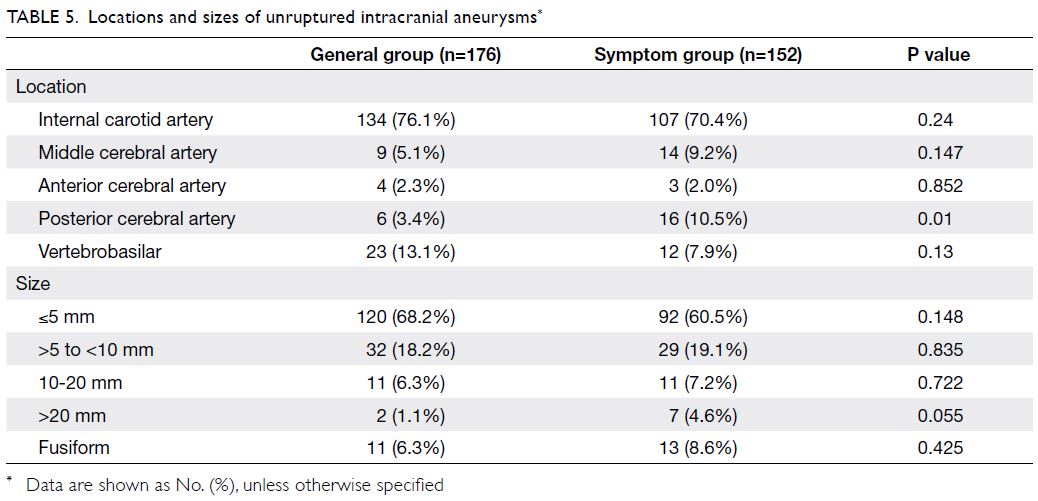

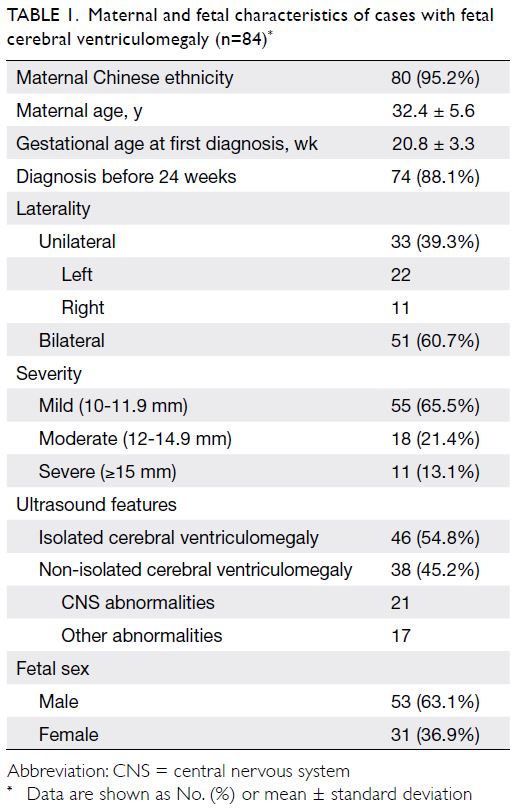

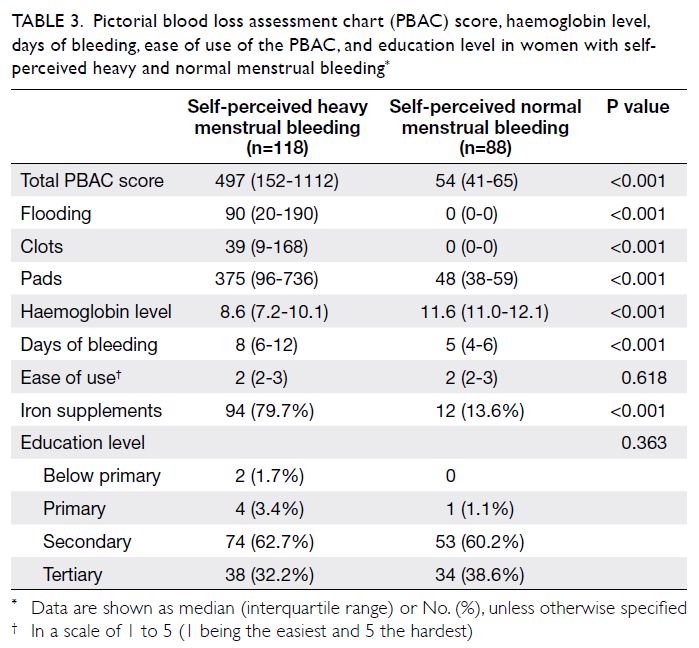

Expectations of a survivorship programme

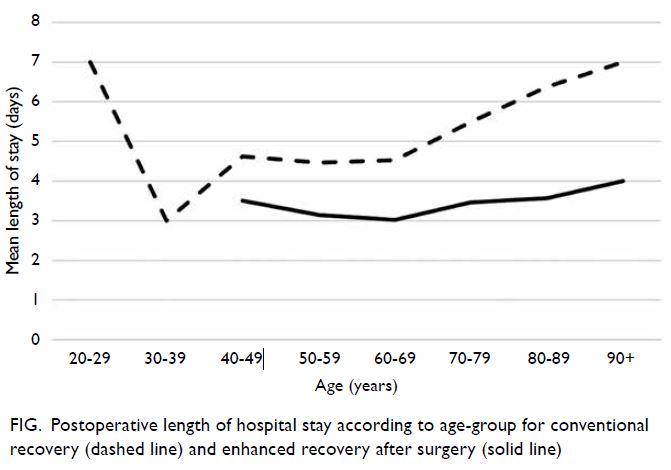

Nearly all participants stated that the provision of

survivorship education (n=168, 84%) and late-effects

screening services (n=157, 78.5%) would be the most

important components of a survivorship programme

(Fig 2). Moreover, helping survivors to understand

and confront the fear of relapse (n=161, 80.5%) and

addressing psychological distress (n=154, 77%) were

the most popular psychosocial services. Among

parents (n=45), learning how to parent a child with

cancer (n=36, 80%) and psychosocial support for

parents (n=33, 73.3%) were regarded as essential

components.

Figure 2. Expectations of survivorship programme among adult survivors and parents of paediatric survivors of childhood cancer (n=200)

Most participants (n=81, 40.5%) stated that

their preferred enrolment time into a survivorship

programme would be at the initiation of cancer

treatment; some participants (n=58, 29.0%) stated

that their preferred enrolment time would be

during the transition from active treatment to

follow-up (Table 5). In terms of modes of services,

most respondents preferred dialogue sessions with

healthcare professionals (n=156, 78.0%), interactive

platforms (n=100, 50.0%), and support groups

(n=101, 50.5%) [Table 5].

Discussion

Health-protective behaviours

There is growing evidence that physical activity

is a therapeutic strategy that may reduce the risks

of systemic recurrence and mortality in cancer

survivors.22 Similar to findings from other countries,

we found that physical inactivity was highly

prevalent among survivors of childhood cancer.9 23

This observation was not surprising, considering that the rate of physical activity is low among the

general population in Hong Kong; only 40% to 46% of

children and youth met physical activity guidelines

for a mean duration of 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous

physical activity per day.24 Although we did

not identify any significant predictors of physical

inactivity, this large proportion of inactive survivors

indicates the need to further explore the reasons

for this phenomenon and devise interventions to

address them. For example, interventions targeting

the survivor–parent dyad may promote common

lifestyle behaviours within the families of survivors.25

Moreover, local adventure-based training and

experiential learning programmes may enhance self-efficacy

in survivors, thereby empowering them to

initiate and maintain a physically active lifestyle.26 27

Our study found that only 38% of survivors

reported frequently consuming a balanced diet.

For example, survivors of CNS tumours were

more likely to have poor dietary habits, compared

with survivors of non-CNS malignancies. This is

concerning because patients with CNS tumours are

more vulnerable to developing metabolic syndromes related to complications associated with cranial

radiation and neurosurgery. Poor dietary habits may

further exacerbate the disease course of these late

effects.28 This finding suggests that dietitians should

give advice regarding stricter dietary control to

optimise the health of CNS cancer survivors in Hong

Kong.

Despite the extensive promotion of the seasonal

influenza vaccination programme by the Hong Kong

Special Administrative Region Government,29 only

30% of survivors indicated that they had received the

influenza vaccine in the past year. Younger survivors

were more likely to have participated in vaccination

programmes, probably because school-age children

are generally enrolled into the government

immunisation programme that provides the hepatitis

B, pneumococcal, and annual influenza vaccines, as

well as the recently added human papillomavirus

(HPV) vaccine.30 We acknowledge that our findings

must be interpreted with caution because survivors

might inaccurately recall or report their vaccination

histories. However, these results have two important

implications that warrant attention from the medical community. First, there is a need to educate

survivors regarding the role of vaccination in

preventing severe complications from infection (eg,

influenza and pneumococcal vaccines for preventing

seasonal flu and pneumonia, respectively) and

other malignancies (eg, HPV vaccine for preventing

cervical cancer). In particular, collaborations among

schools and community physicians may help promote

the uptake of HPV vaccines among adolescent

female survivors.31 32 Second, children treated

with chemotherapy for childhood malignancies

reportedly may develop acquired immunological

defects in both cell-mediated and humoral immunity,

resulting in the loss of protection conferred by

prior vaccinations.33 Future work should involve

the development of clinical consensus guidelines

regarding vaccination administration schedules

for non-transplant survivors of childhood cancer,

particularly survivors who have received intensive

chemotherapy treatment.

Health-damaging behaviours

Similar to the findings of Chan et al,13 we found that

health-damaging practices are uncommon among

local survivors. Both drinking and smoking rates

were lower in this study than in studies from other

developed countries.9 19 34 However, the reported rate

(20.5%) of exposure to second-hand smoke in the

home was surprisingly high. We speculate that this

high rate is because the smoking rates of individuals

above the age of 40 years remain relatively high in the

general population (16.9% to 26.2% in men and 1.3% to

5.1% in women).35 Older family members, particularly

men, might remain the main source of second-hand

smoke for survivors. This observation underscores

the need for continual efforts to encourage survivors

to abstain from harmful health practices (particularly

during the early survivorship phase) and the need for

smoking cessation interventions to be provided for

the comparatively few survivors and family members

who are current smokers.

Socioeconomic factors

In this study, lower socioeconomic status was

significantly associated with poor health practices.

The association between possession of private

medical insurance and immunisation practice was

close to statistically significant, further suggesting

that socioeconomic disparities hinder access to

preventive care among cancer survivors. Underserved

survivors may require special navigation services to

support their adherence to surveillance, preventive

care, and health-protective behaviours.36 Considering

that only half of the survivors had private health

insurance, collaborations between clinicians and

policymakers could enable the establishment of

a universal vaccination and late-effects screening

programme for cancer survivors. Local research is

needed to identify barriers to—and facilitators of—quality care and effective methods of outreach to

underserved survivors.

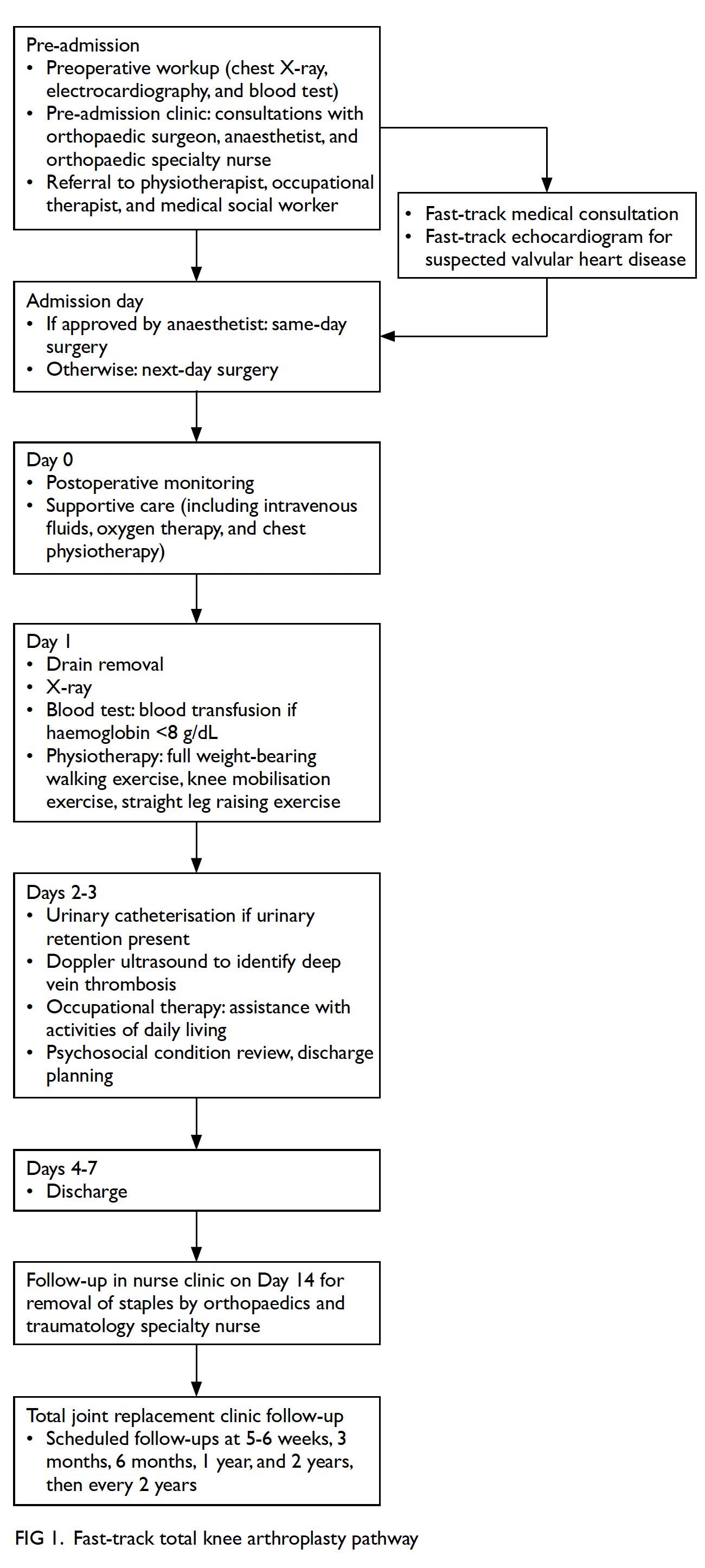

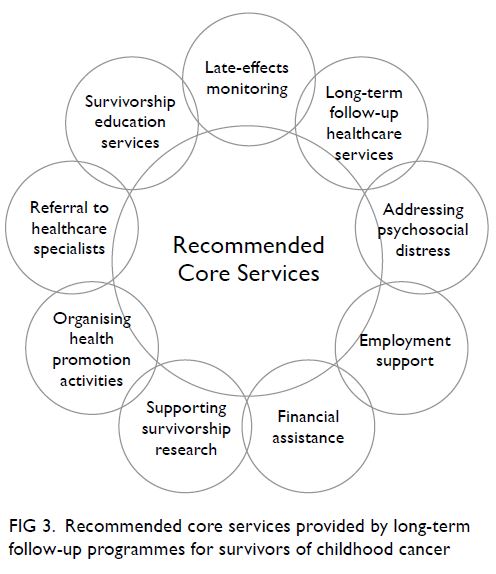

Survivorship care

Most survivors indicated that they would prefer to be

enrolled into a survivorship programme early in the

cancer care continuum. This is a promising prospect

because survivors who had early access to structured

survivorship programmes reportedly were more

aware of their late effects, visited emergency

departments less frequently, had higher cancer-specific

health literacy, and tended to experience

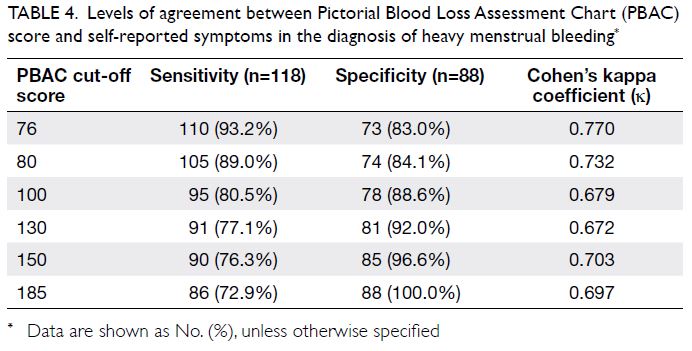

less emotional stress.3 Therefore, a structured

survivorship programme is recommended to include

cancer and late-effects screening, a specialist referral

network, and psychosocial services for survivors and

caregivers (Fig 3).4 12 In Hong Kong, the five major institutions that provide paediatric oncology care

typically include these core services in their long-term

follow-up programmes, although the specific

services offered may differ among institutions.

Overall, the centralisation of paediatric oncology

services in the new Hong Kong Children’s Hospital

has provided an unprecedented opportunity for

oncologists and allied health professionals to initiate

a formal paediatric cancer survivorship programme

in Hong Kong. This will facilitate the development

of a survivorship care model that is tailored to the

healthcare system in Hong Kong.

Figure 3. Recommended core services provided by long-term follow-up programmes for survivors of childhood cancer

Our participants regarded services concerning

health issues (eg, education and screening for late

effects) as the most important aspects of survivorship

care. The COG has developed a set of “risk-based”

guidelines, which refer to a personalised systematic

plan of regular screening, surveillance, and

prevention strategies based on a patient’s treatment,

cancer experience, and personal factors.5 10 In an

effort to improve the awareness of health issues in

Chinese cancer survivors, we collaborated with the

COG and launched a Chinese version of the Health

Links patient education materials in May 2020.10 To

our knowledge, this is the first set of publicly available

authoritative resources regarding late effects that is

written in a native Chinese language. Such initiatives

are anticipated to assist survivors in taking age-appropriate

ownership of their health and engaging

as active partners with their health providers during

the survivorship phase.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in the context

of the following limitations. First, this single-centre

study comprised a moderately small sample of

survivors who were recruited through a convenience

sampling approach. Moreover, eligible participants

were identified from a long-term follow-up clinic

that had a mean loss to follow-up rate of 15% to

20%. This is a recognised challenge in survivorship

research because this population is often lost to

follow-up from primary paediatric clinics as a

result of their growing independence and mobility

during advancement into adulthood.37 These study

limitations may have introduced sampling bias

because our participants may have been more likely

to be health conscious than non-participants and

survivors who had been lost to follow-up. Hence,

the true uptake of health-protective behaviours

among local survivors may be lower than the rates

reported in this study, and our findings might not

be generalisable to other survivors of childhood

cancer in Hong Kong. Second, social desirability

and recall bias may have affected the accuracy of the

self-reported results. Future studies should adopt

validated and more sensitive instruments to achieve

a more objective evaluation of health behaviour. For example, physical activity and sleep can be

better measured with actigraphy studies. Finally, the

multiple predictors and covariates analysed in this

study may have increased the risk of a Type I error.

However, lifestyle itself is a complex phenotype that

is likely to be influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic

factors. Our findings should be validated using a

larger-scale study that involves the prospective

collection of outcome data to better reflect the

trajectory of health behaviour changes and correlate

these findings with the results in local cancer

survivors.

Conclusion

Despite the low prevalences of health-damaging

behaviours, the frequencies with which Hong Kong

survivors of childhood cancer engaged in health-protective

behaviours were unsatisfactory. These

findings highlight the need to empower survivors

to adopt health-protective behaviours. A potential

intervention opportunity may involve engaging

survivors and families in a structured comprehensive

survivorship programme during their transition to

survivorship. A multidisciplinary and interactive

programme addressing late effects and psychosocial

aspects may address the multifaceted needs of

Hong Kong survivors of childhood cancer. Future

work should aim to improve preventive care for

underserved groups through advocacy and care

coordination.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YT Cheung, LS Yang, JCT Ma, PHK Woo, TCH Chan, SMS Luk.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YT Cheung, LS Yang, JCT Ma, PHK Woo, TCH Chan, SMS Luk.

Drafting of the manuscript: YT Cheung, TCH Chan, SMS Luk.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YT Cheung, LS Yang, JCT Ma, PHK Woo, TCH Chan, SMS Luk.

Analysis or interpretation of data: YT Cheung, LS Yang, JCT Ma, PHK Woo, TCH Chan, SMS Luk.

Drafting of the manuscript: YT Cheung, TCH Chan, SMS Luk.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Smita Bhatia and Dr Wendy Landier from

the Institute for Cancer Outcomes and Survivorship,

The University of Alabama in Birmingham, for serving as

consultants on this project.

Declaration

A portion of this work was presented at the 52nd Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP)–Virtual conference (14-17 October 2020), as well as the HKPS/HKCOP/HKPNA/HKCPN Joint Annual Scientific

Meeting on 7 November 2020.

Funding/support

This study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund Research Fellowship, the Food and Health Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Ref 03170047).

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 2018.338). Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer

Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2014. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed 3 Sep

2020.

2. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Cancer in children and

adolescents (0-18 years). Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/children.asp. Accessed 3 Sep 2020.

3. Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, et al. The impact of

long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors: a

systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2017;114:131-8. Crossref

4. Children’s Oncology Group Nursing Discipline Clinical

Practice Subcommittee/Survivorship in collaboration

with the Late Effects Committee. Establishing and

enhancing services for childhood cancer survivors. Long-term

follow-up program resource guide. 2007. Available from: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/LTFUResourceGuide.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2020.

5. Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development

of risk-based guidelines for paediatric cancer survivors:

the Children’s Oncology Group long-term follow-up

guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group Late

Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol

2004;22:4979-90. Crossref

6. Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical

ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated

for childhood cancer. JAMA 2013;309:2371-81. Crossref

7. Poon LH, Yu CP, Peng L, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes in Asian survivors of childhood cancer: a

systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2019;13:374-96. Crossref

8. Dixon SB, Bjornard KL, Alberts NM, et al. Factors influencing risk-based care of the childhood cancer survivor

in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:133-52. Crossref

9. Ford JS, Barnett M, Werk R. Health behaviours of childhood cancer survivors. Children (Basel) 2014;1:355-73. Crossref

10. Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and

young adult cancers, version 5.0. October 2018. Available

from: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/2018/COG_LTFU_Guidelines_v5.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2020.

11. George SM, Smith AW. Commentary: understanding risk

behaviour among adolescent cancer survivors–are they

more like healthy adolescents or is cancer a teachable

moment? A commentary on Klosky and colleagues’ article

on health behaviours in survivors of childhood cancer and

their siblings. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:647-9. Crossref

12. Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, Rowland JH. Going

beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in

cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1978-81. Crossref

13. Chan CW, Choi KC, Chien WT, et al. Health behaviours

of Chinese childhood cancer survivors: a comparison

study with their siblings. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2020;17:6136. Crossref

14. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Department of Health & Human Services. Youth risk

behaviour surveillance–United States, 2013. Available

from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/dear_colleague/2014/dcl-061314-hiv-prep.html. Accessed 4 Sep 2020.

15. Lown EA, Hijiya N, Zhang N, et al. Patterns and predictors

of clustered risky health behaviours among adult survivors

of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer

Survivor Study. Cancer 2016;122:2747-56. Crossref

16. Klosky JL, Howell CR, Li Z, et al. Risky health behaviour

among adolescents in the childhood cancer survivor study

cohort. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:634-46. Crossref

17. Health and Medical Research Fund, Food and Health

Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. Research Fellowship

Scheme Approved Projects since 2016-17. Ref 03170047:

Personalized risk-based care and education for early

survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Available

from: https://rfs2.fhb.gov.hk/images/fundedproject/Approved_Projects_Fellowship.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

18. Landier W, Chen Y, Namdar G, et al. Impact of tailored education on awareness of personal risk for therapy-related complications among childhood cancer survivors.

J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3887-93. Crossref

19. Lown EA, Goldsby R, Mertens AC, et al. Alcohol consumption patterns and risk factors among childhood

cancer survivors compared to siblings and general

population peers. Addiction 2008;103:1139-48. Crossref

20. Devine KA, Mertens AC, Whitton JA, et al. Factors

associated with physical activity among adolescent

and young adult survivors of early childhood cancer: a

report from the childhood cancer survivor study (CCSS).

Psychooncology 2018;27:613-9. Crossref

21. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism,

National Institute of Health, US Government. Drinking

levels defined. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed 3 Sep 2020.

22. Cormie P, Zopf EM, Zhang X, Schmitz KH. The impact of

exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence, and treatment-related

adverse effects. Epidemiol Rev 2017;39:71-92. Crossref

23. Ness KK, Leisenring WM, Huang S, et al. Predictors of

inactive lifestyle among adult survivors of childhood

cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor

Study. Cancer 2009;115:1984-94. Crossref

24. Huang WY, Wong SH, Sit CH, et al. Results from the Hong

Kong’s 2018 report card on physical activity for children

and youth. J Exerc Sci Fit 2019;17:14-9. Crossref

25. Badr H, Paxton RJ, Ater JL, Urbauer D, Demark-Wahnefried W. Health behaviours and weight status of childhood cancer survivors and their parents: similarities

and opportunities for joint interventions. J Am Diet Assoc

2011;111:1917-23. Crossref

26. Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY, Chiu SY, Lopez V. Effectiveness

of an integrated adventure-based training and health

education program in promoting regular physical activity

among childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology

2013;22:2601-10. Crossref

27. Ruble K, Scarvalone S, Gallicchio L, Davis C, Wells D.

Group physical activity intervention for childhood cancer

survivors: a pilot study. J Phys Act Health 2016;13:352-9. Crossref

28. Smith WA, Li C, Nottage KA, et al. Lifestyle and metabolic

syndrome in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a

report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Cancer

2014;120:2742-50. Crossref

29. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Vaccination subsidy scheme–general public. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/features/46107.html. Accessed 14 Sep 2020.

30. Family Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Child health. Schedule of Hong Kong

Childhood Immunisation Programme. Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/main_ser/child_health/child_health_recommend.html. Accessed 14 Sep 2020.

31. Chau JP, Lo SH, Choi KC, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary

team-led school-based human papillomavirus vaccination

health-promotion programme on improving vaccine

acceptance and uptake among female adolescents: a

cluster randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore)

2020;99:e22072. Crossref

32. Yuen WW, Lee A, Chan PK, Tran L, Sayko E. Uptake of

human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Hong Kong:

facilitators and barriers among adolescent girls and their

parents. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194159. Crossref

33. Han JH, Harmoney KM, Dokmeci E, et al. Dynamic

re-immunization of off-treatment childhood cancer

survivors: an implementation feasibility study. PLoS One

2018;13:e0191804. Crossref

34. Gibson TM, Liu W, Armstrong GT, et al. Longitudinal

smoking patterns in survivors of childhood cancer: an

update from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer

2015;121:4035-43. Crossref

35. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Pattern of smoking. In: Census and Statistics

Department, The Government of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region. Hong Kong Monthly Digest of

Statistics January 2019. Available from: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10100022019MM01B0100.pdf. Accessed 14 Sep 2020.

36. Lee Smith J, Hall IJ. Advancing health equity in cancer survivorship: opportunities for public health. Am J Prev

Med 2015;49:S477-82. Crossref

37. Rokitka DA, Curtin C, Heffler JE, Zevon MA, Attwood K,

Mahoney MC. Patterns of loss to follow-up care among

childhood cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol

2017;6:67-73. Crossref