Ten-year refractive and visual outcomes of intraocular lens implantation in infants with congenital cataract

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

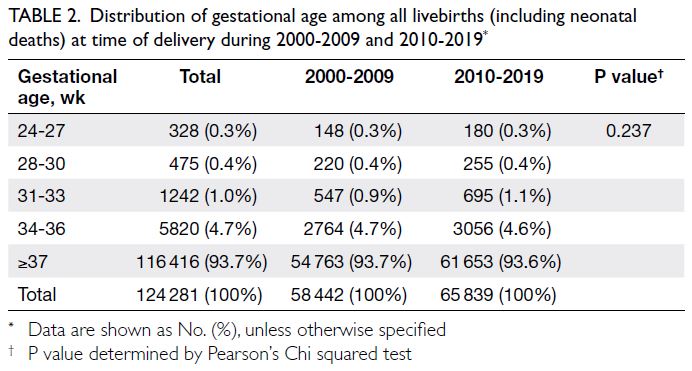

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Ten-year refractive and visual outcomes of

intraocular lens implantation in infants with congenital cataract

Joyce JT Chan, FRCOphth; Emily S Wong, FCOphthHK; Carol PS Lam, FCOphthHK; Jason C Yam, FRCSEd

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Eye Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr JC Yam (yamcheuksing@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: There is no consensus regarding

optimal target refraction after intraocular lens

implantation in infants. This study aimed to clarify

relationships of initial postoperative refraction with

long-term refractive and visual outcomes.

Methods: This retrospective review included 14

infants (22 eyes) who underwent unilateral or

bilateral cataract extraction and primary intraocular

lens implantation before the age of 1 year. All infants

had ≥10 years of follow-up.

Results: All eyes exhibited myopic shift over a mean

follow-up period of 15.9 ± 2.8 years. The greatest

myopic shift occurred in the first postoperative

year (mean=-5.39 ± +3.50 dioptres [D]), but

smaller amounts continued beyond the tenth

year (mean=-2.64 ± +2.02 D between 10 years

postoperatively and last follow-up). Total myopic

shift at 10 years ranged from -21.88 to -3.75 D

(mean=-11.62 ± +5.14 D). Younger age at operation

was correlated with larger myopic shifts at 1 year

(P=0.025) and 10 years (P=0.006) postoperatively.

Immediate postoperative refraction was a predictor

of spherical equivalent refraction at 1 year

(P=0.015) but not at 10 years (P=0.116). Immediate postoperative refraction was negatively correlated

with final best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA)

(P=0.018). Immediate postoperative refraction of

≥+7.00 D was correlated with worse final BCVA

(P=0.029).

Conclusion: Considerable variation in myopic

shift hinders the prediction of long-term refractive

outcomes in individual patients. When selecting

target refraction in infants, low to moderate

hyperopia (<+7.00 D) should be considered to

balance the avoidance of high myopia in adulthood

with the risk of worse long-term visual acuity related

to high postoperative hyperopia.

New knowledge added by this study

- The greatest myopic shift occurred in the first year after cataract surgery, but smaller shifts continued beyond the tenth year. Overall, 50% of eyes exhibited myopic shift >-2.00 dioptres between the tenth postoperative year and last follow-up.

- Considerable variation in refractive change after intraocular lens implantation in infants aged <1 year hinders the prediction of long-term refractive outcomes in individual patients. Immediate postoperative refraction was not correlated with spherical equivalent refraction at 10 years postoperatively.

- Immediate postoperative refraction of ≥+7.00 dioptres was correlated with worse final visual acuity.

- When selecting target refraction in infants, low to moderate hyperopia (<+7.00 dioptres) should be considered to balance the avoidance of high myopia in adulthood with the risk of worse long-term visual acuity related to high postoperative hyperopia.

Introduction

Appropriate optical correction after cataract

extraction in infants is important for efforts to

avoid amblyopia. Primary intraocular lens (IOL)

implantation allows constant in situ optical correction

during the critical years of visual development,

while avoiding the expenses and compliance issues

associated with contact lenses.1 Disadvantages

include increased rates of surgical complications and re-operations,2 as well as the inability to modify IOL power during ocular growth. A recent report by the

American Academy of Ophthalmology suggested

that IOL implantation can be safely conducted in

children aged >6 months.3 However, because of the

unpredictable nature of ocular growth, it remains

challenging to select a target refraction in infants

that allows achievement of optimal long-term visual

and refractive outcomes.

Surgeons target various initial hyperopia

values, ranging from +5.00 dioptres (D) to +10.50 D,4 5 6 7 8 9

to compensate for the rapid myopic shift that

occurs during infancy. However, prediction of the

myopic shift remains difficult; significant hyperopia

in infants requires stringent optical correction to

prevent amblyopia, and some studies have linked

high initial hyperopia to worse visual acuity.10 11 This

retrospective study aimed to clarify the relationships

of initial postoperative refraction with 10-year

spherical equivalent refraction (SER) and long-term

best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) after IOL

implantation in infants.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This retrospective study included patients who

underwent unilateral or bilateral congenital cataract

extraction and primary IOL implantation before

the age of 1 year between 1997 and 2009 at a single

secondary and tertiary referral eye centre. Only

patients with ≥10 years of follow-up were included.

Eyes with associated ocular co-morbidities (eg,

persistent foetal vasculature and glaucoma) were

excluded.

Surgical technique and follow-up

The patients’ baseline characteristics (eg, age, axial

length [determined by applanation A-scan biometry],

and keratometry) were recorded. Intraocular lens

powers were calculated using the Sanders–Retzlaff–Kraff II formula. The operating surgeon selected

the target refraction and IOL power, considering

the patient’s age (all cases) and refractive error in

the fellow eye (unilateral cases). All operations

were performed using similar techniques, including

the creation of a 3.0-mm scleral tunnel, anterior

continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis, and lens

removal by automated irrigation and aspiration.

Heparin-surface-modified polymethyl methacrylate

IOLs or acrylic foldable IOLs were implanted. The

IOL was placed in the capsular bag or in the sulcus.

All wounds were sutured. In some cases, primary

posterior curvilinear capsulorhexis and anterior

vitrectomy were performed. Because of reports

that a significant number of eyes in young infants

required secondary posterior capsule opening

despite primary posterior capsulotomy,12 13 this

procedure was omitted in some eyes to increase the

likelihood of achieving capsular IOL implantation.

Postoperatively, all eyes were treated with intensive

topical steroid and antibiotic medication. Patients

were assessed on postoperative day 1, week 1, week

2, and week 4; they were then assessed every 3 to

6 months. When clinically significant posterior

capsular opacification developed, secondary

posterior capsulotomy was performed promptly. Glasses were used for postoperative optical

correction; in some cases, contact lenses were

also used. Amblyopia treatment by patching was

performed as necessary.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Spherical equivalent refraction at 2 weeks

postoperatively was regarded as immediate

postoperative refraction. Serial refractions at each

year of postoperative follow-up were recorded, and

SERs were calculated as the algebraic sum of the

sphere and half the cylindrical power. Postoperative

axial length was measured using non-contact optical

biometry, which was less invasive than applanation

biometry.

Statistical analysis was performed using

Microsoft Excel and SPSS (Windows version 21.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). Best-corrected

visual acuities were converted to logarithm

of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR)

values for statistical analysis. Correlations between

continuous variables were assessed by Spearman

correlation. Differences between groups were

analysed by the Mann–Whitney U test. Preoperative

axial length and keratometry were compared with

values at the last follow-up using the paired-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The independent-sample

Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare

10-year SER and BCVA values among groups with

immediate postoperative refraction ≤+3.50 D, +3.50

to +7.00 D, and ≥+7.00 D. Partial correlation analysis

was performed to detect correlations of immediate

postoperative refraction with spherical refraction

at 1 year and 10 years after adjustment for age at

operation. Multiple linear regression was performed

for multivariate analysis of statistically significant

factors identified during univariate analysis. P values

<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

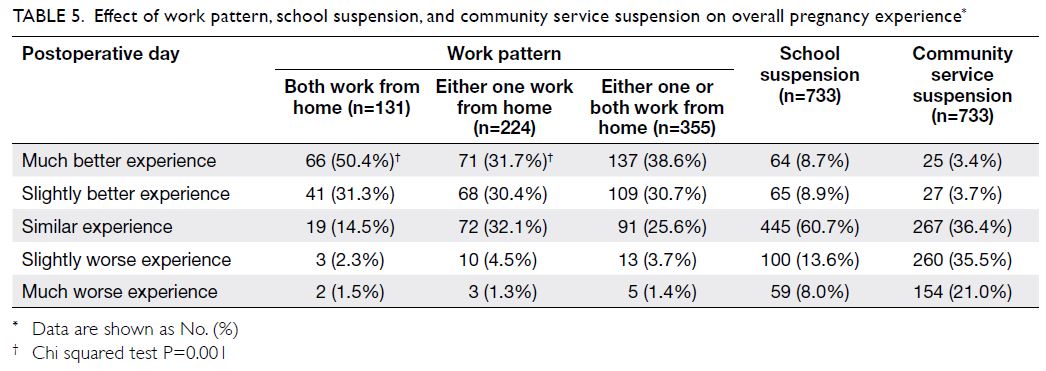

Results

Twenty-two eyes of 14 patients were included in this

study. One eye in one patient with bilateral cataract

was excluded because it was surgically treated after

the patient reached 1 year of age. One eye in another

patient with bilateral cataract was excluded because

it exhibited secondary glaucoma. During surgery,

heparin-surface-modified polymethyl methacrylate

IOLs were implanted in three eyes, whereas acrylic

foldable IOLs were implanted in 19 eyes. The IOL

was placed in the capsular bag in 18 eyes and in the

sulcus in four eyes. Additionally, primary posterior

curvilinear capsulorhexis and anterior vitrectomy

were performed in 13 eyes. For postoperative

optical correction, all 14 patients wore glasses; four

patients (including two with unilateral cataract) also wore contact lenses. Thirteen patients underwent

amblyopia treatment by patching.

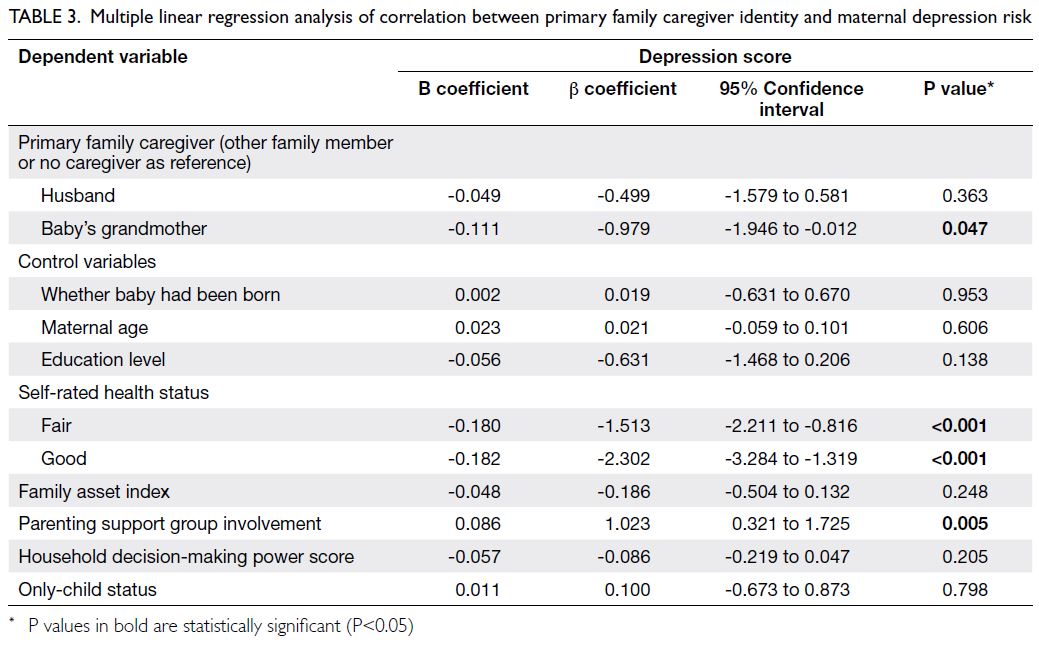

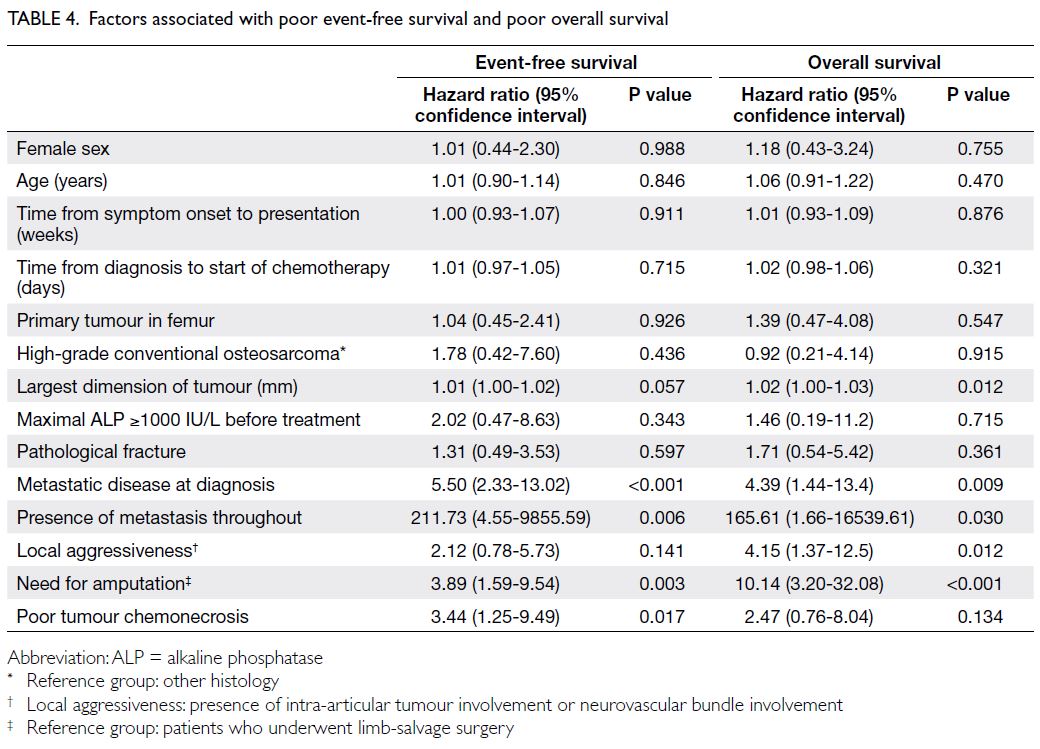

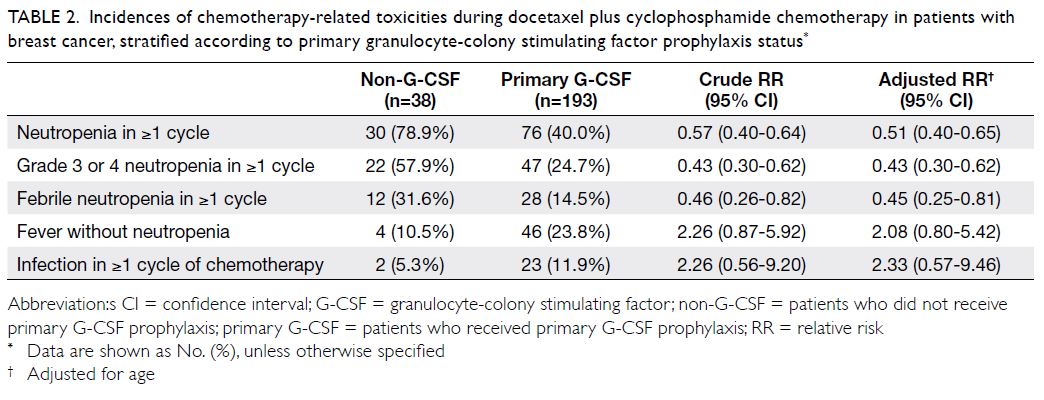

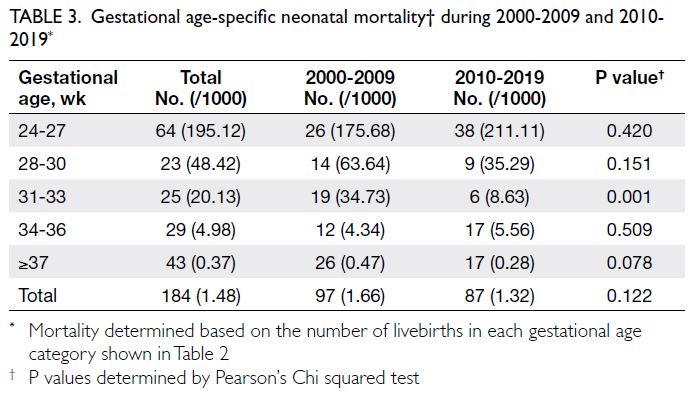

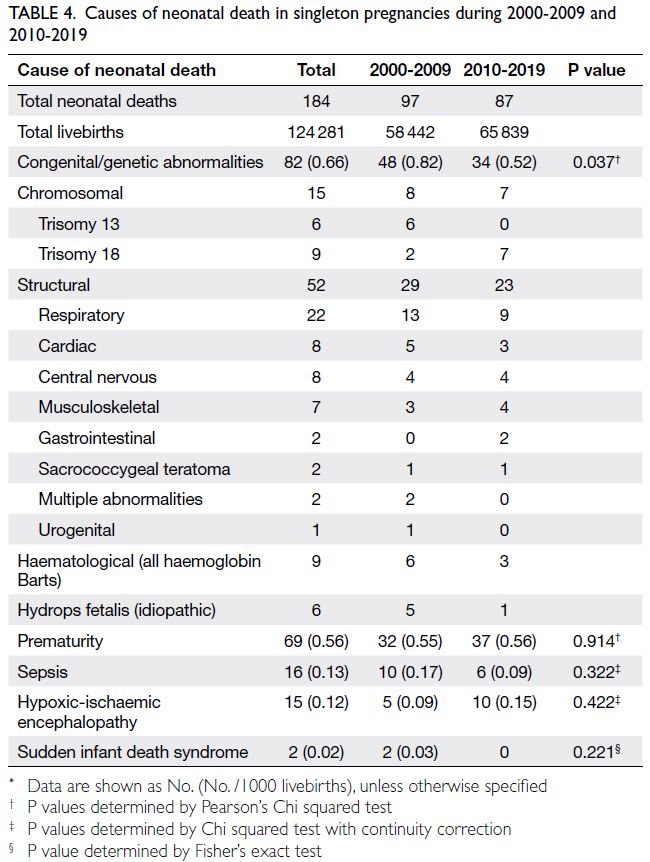

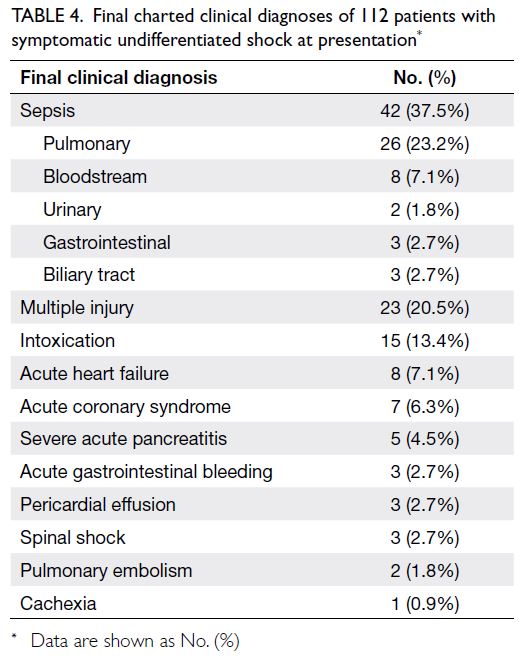

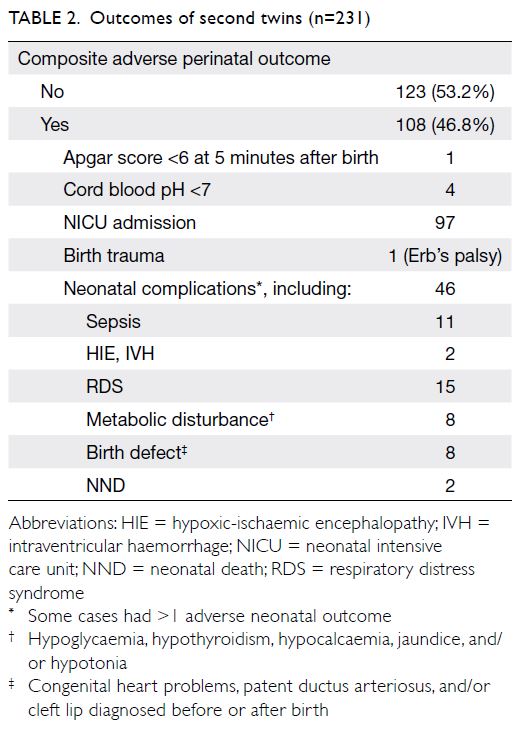

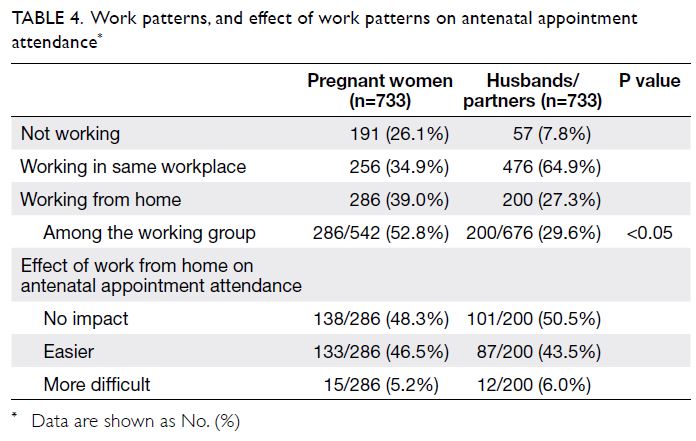

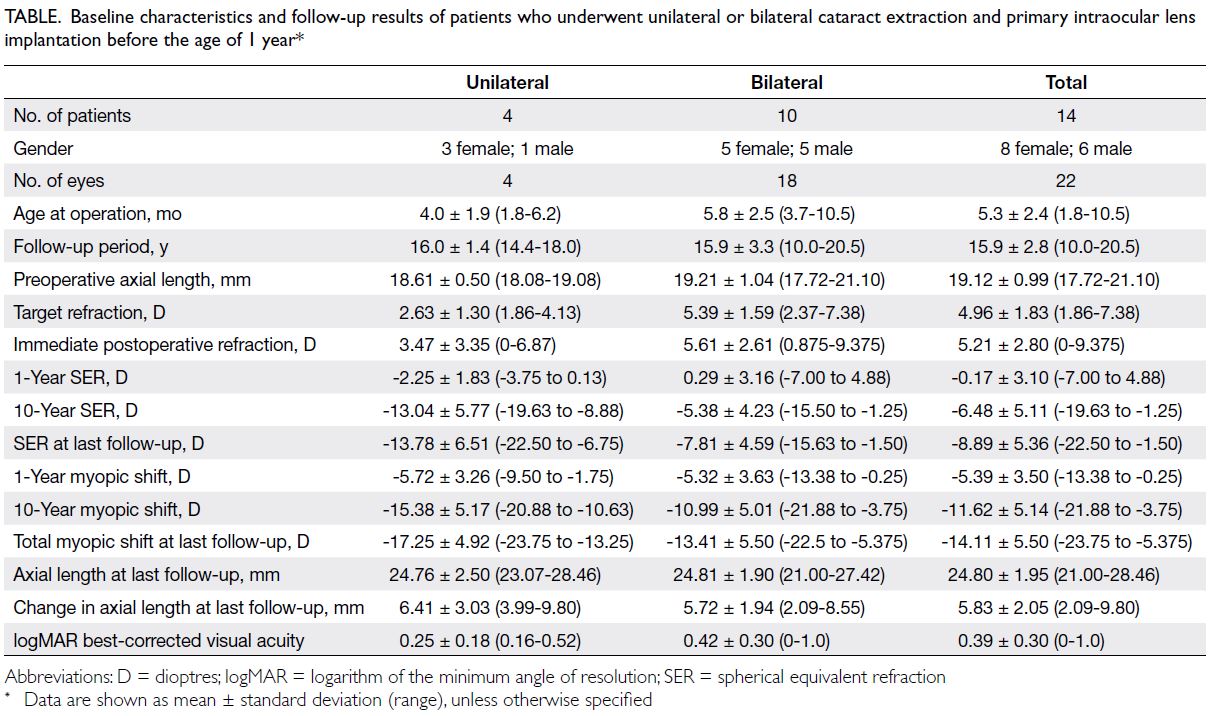

The Table summarises the baseline

characteristics, refractive outcomes, and visual

outcomes of eyes included in this study. All 22 eyes

exhibited myopic shift, ranging from -21.88 to -3.75 D

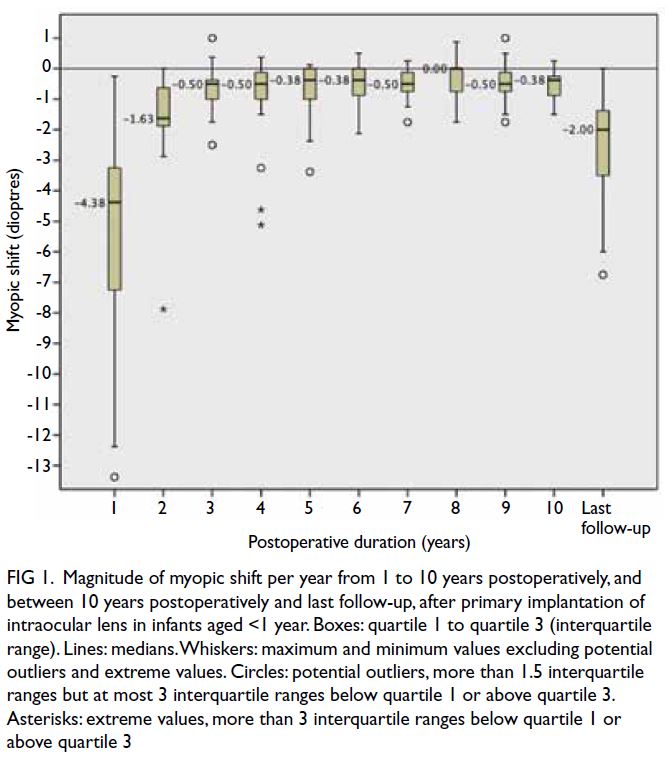

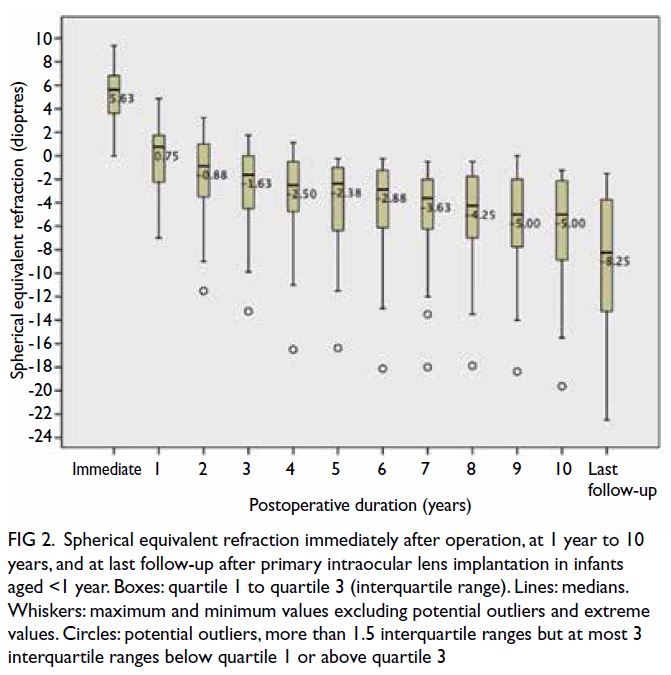

at 10 years. Figures 1 and 2 show the amounts of

myopic shift and SER, respectively, at 1 to 10 years

postoperatively and at last follow-up. The greatest

myopic shift occurred in the first postoperative

year, but smaller shifts continued beyond the tenth

year. Ninety percent of eyes exhibited myopic shift

>-2.00 D between the third postoperative year and

last follow-up (mean myopic shift: -6.40 ± +3.29 D;

range, -12.00 to -1.63 D). These proportions were

82% between the sixth postoperative year and last

follow-up (mean myopic shift: -4.14 ± +2.35 D;

range, -9.38 to -1.13 D), and 50% between the tenth

postoperative year and last follow-up (mean myopic

shift: -2.64 ± +2.02 D; range, -0.125 to -6.75 D).

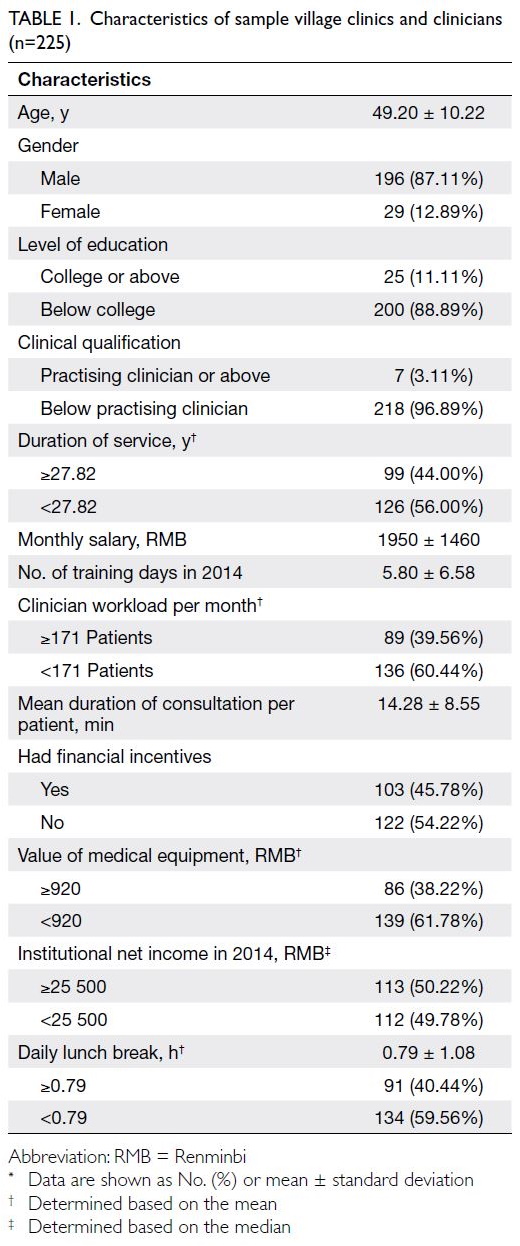

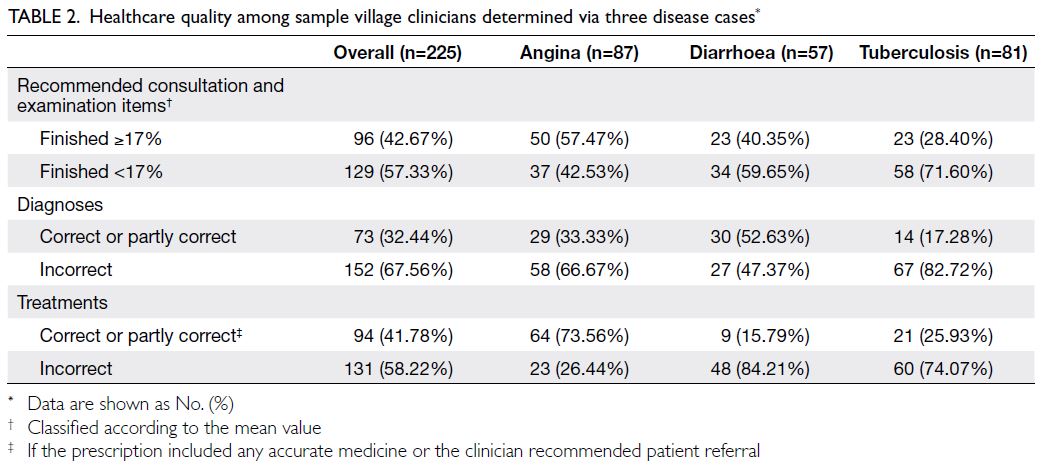

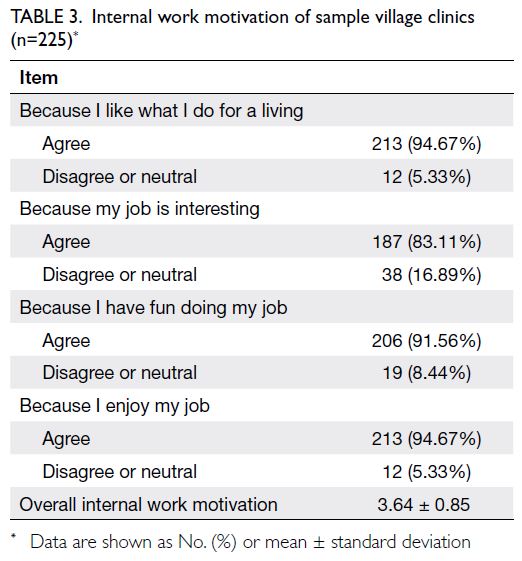

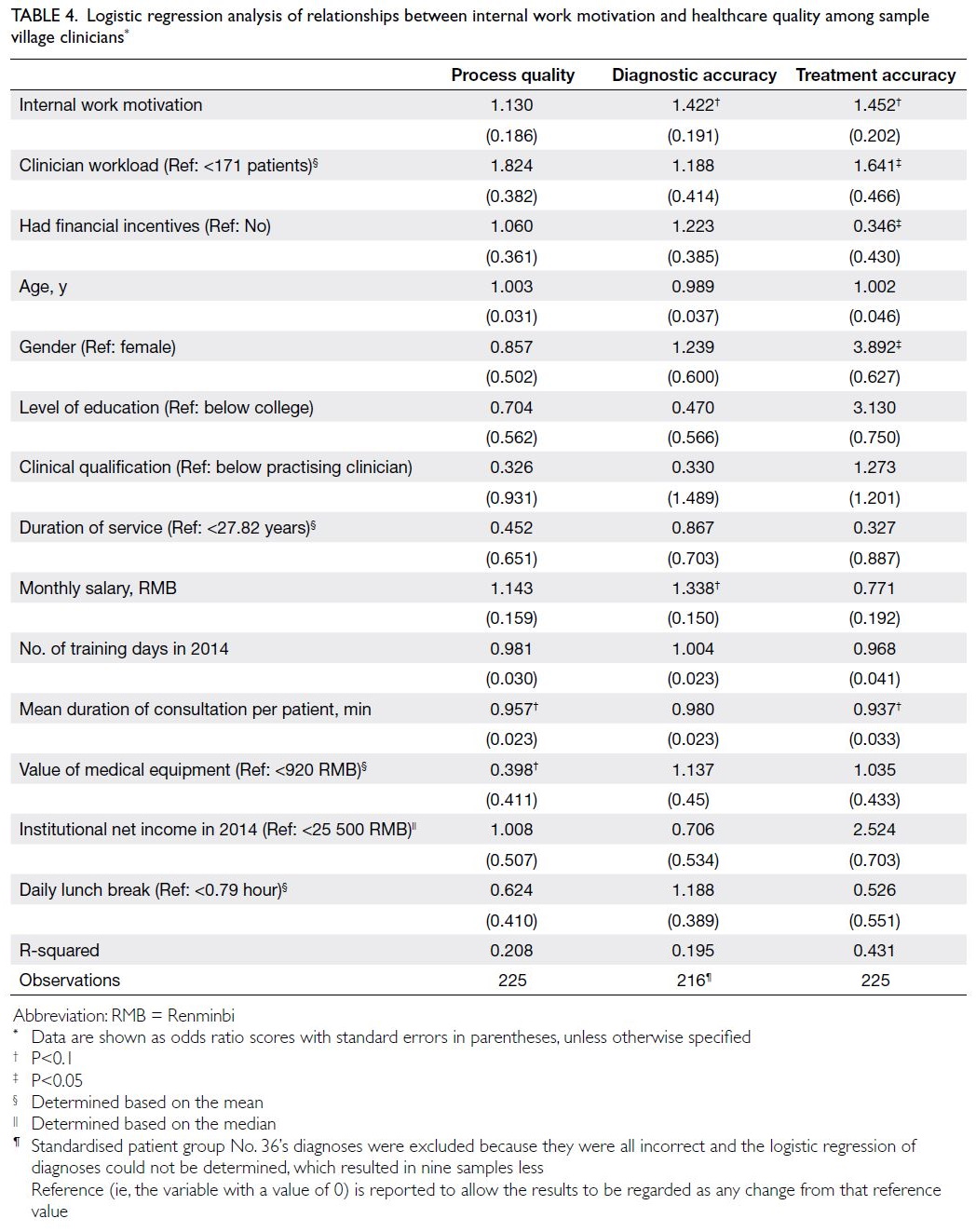

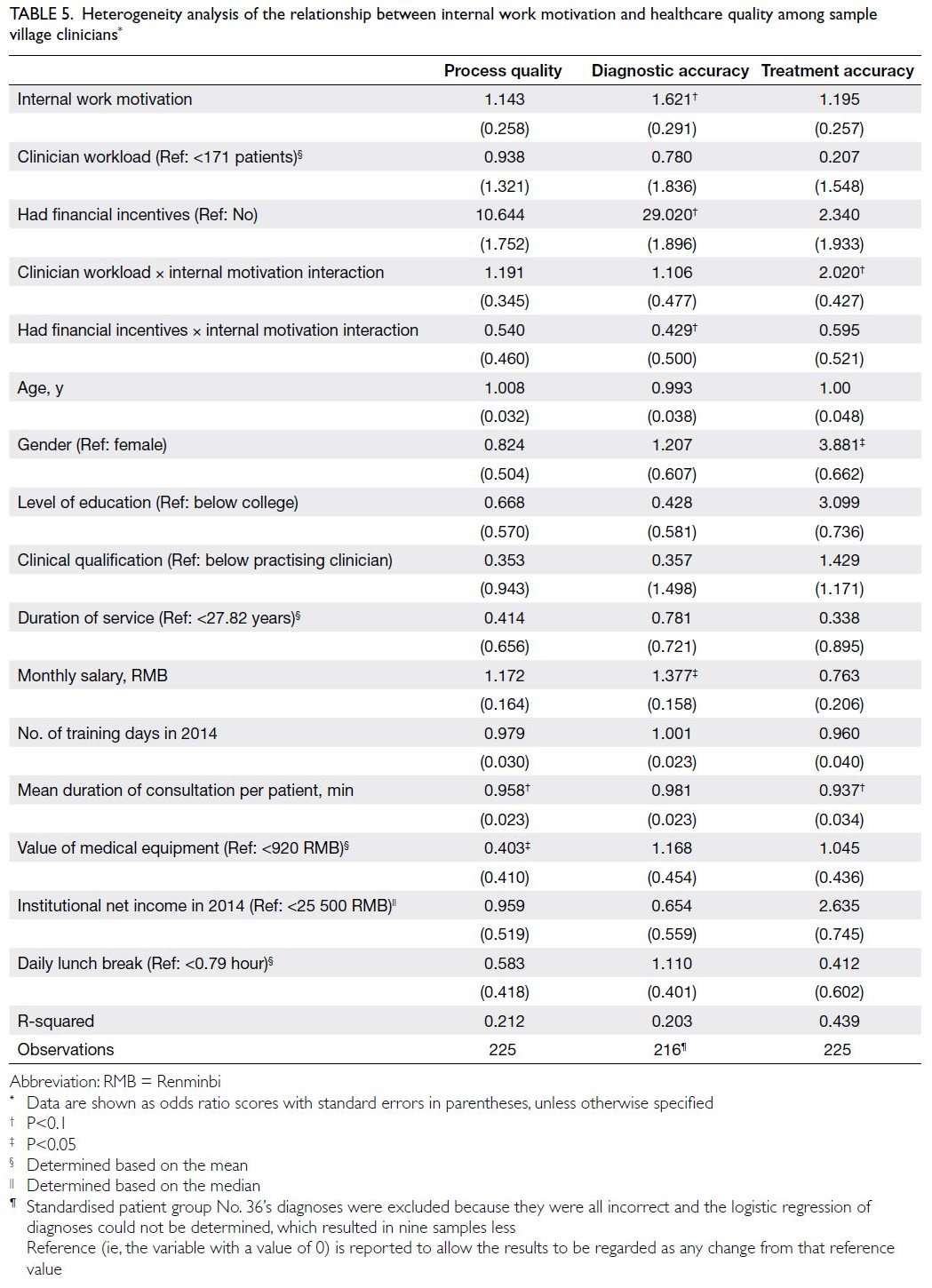

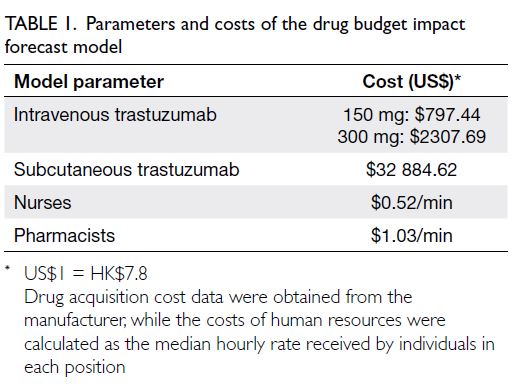

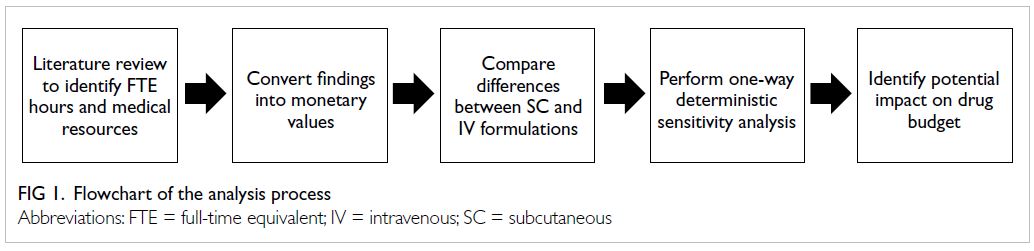

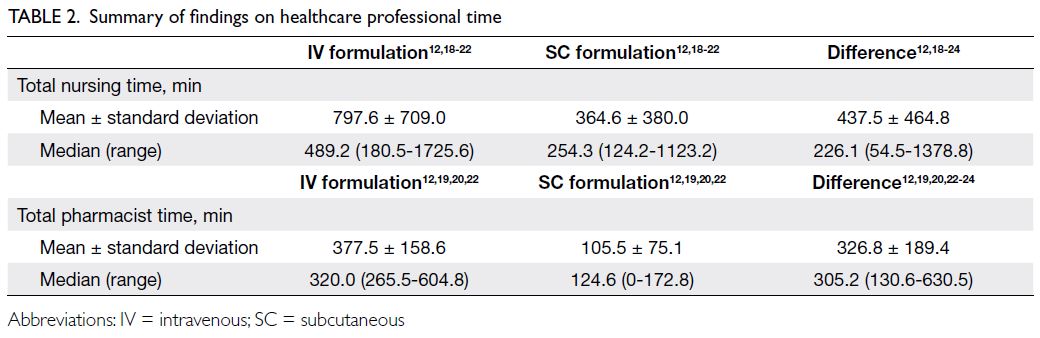

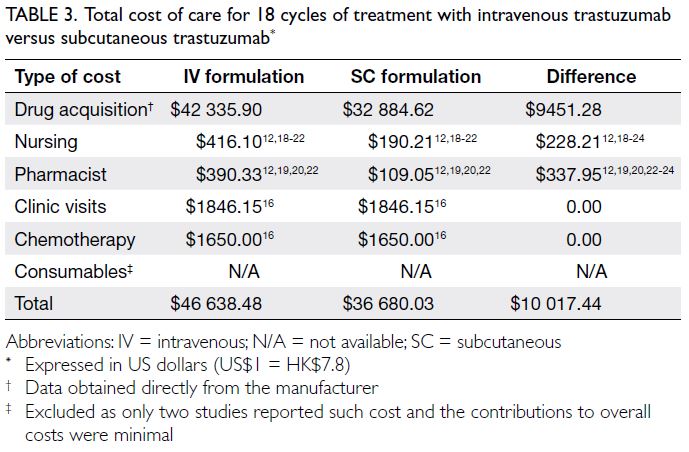

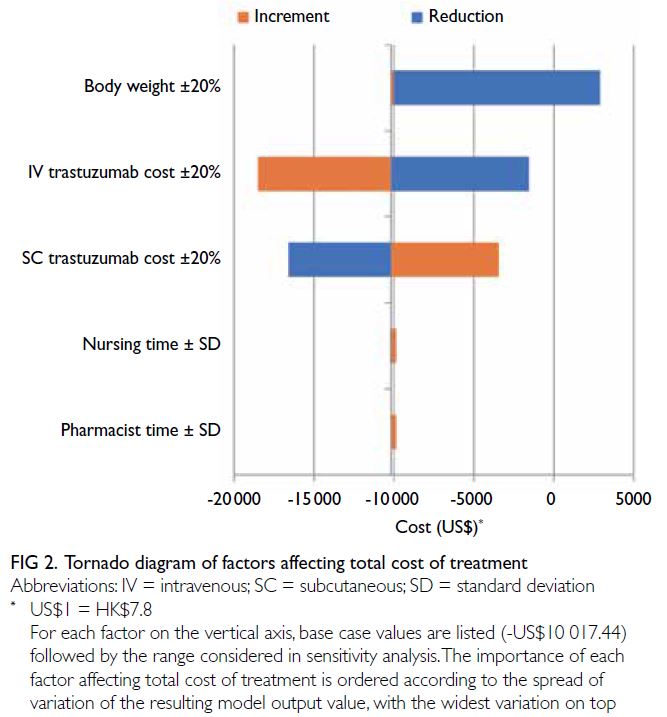

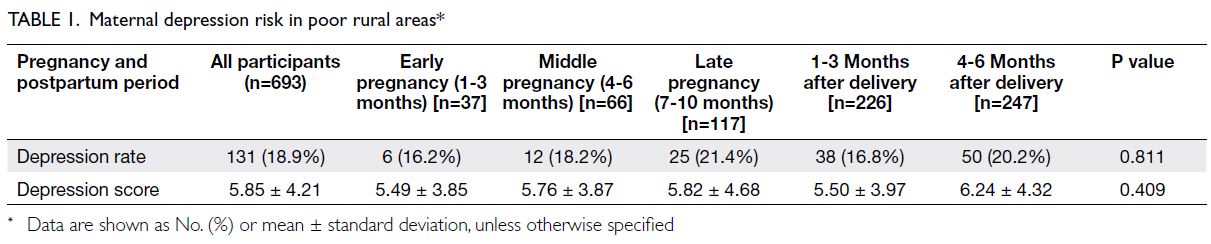

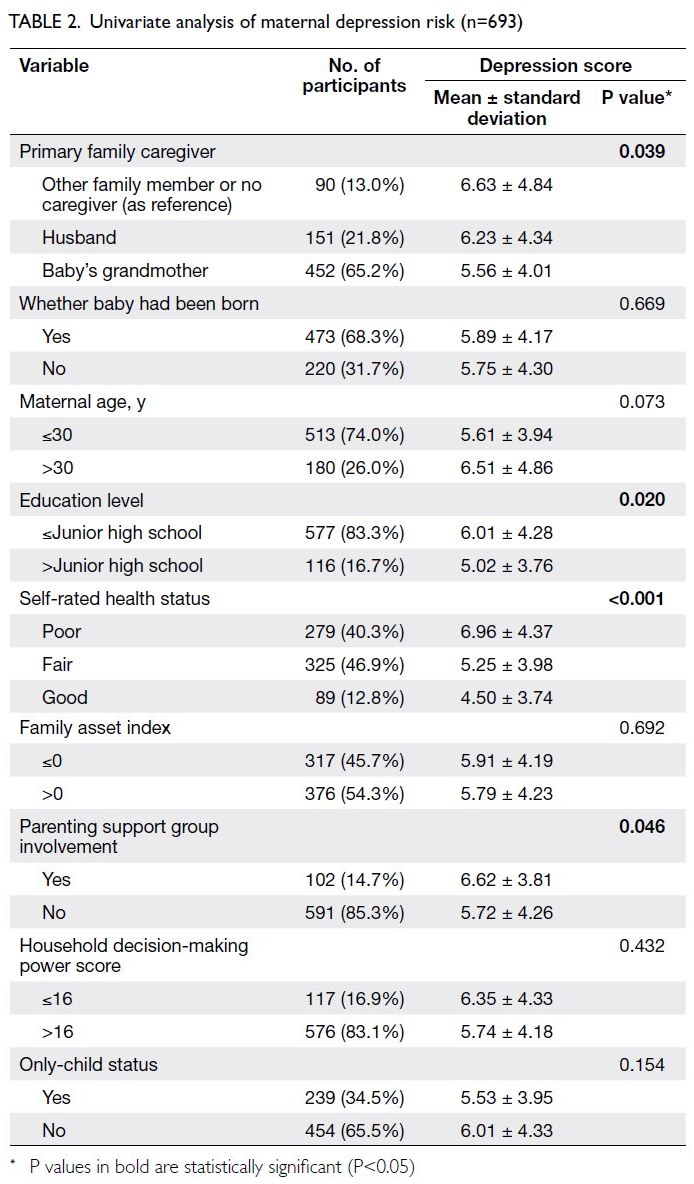

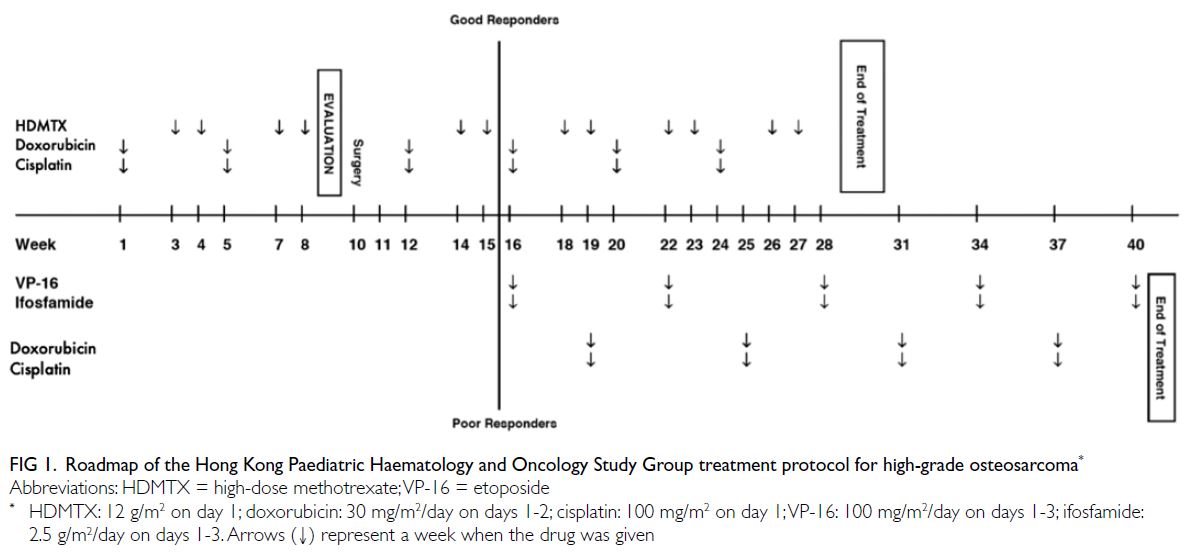

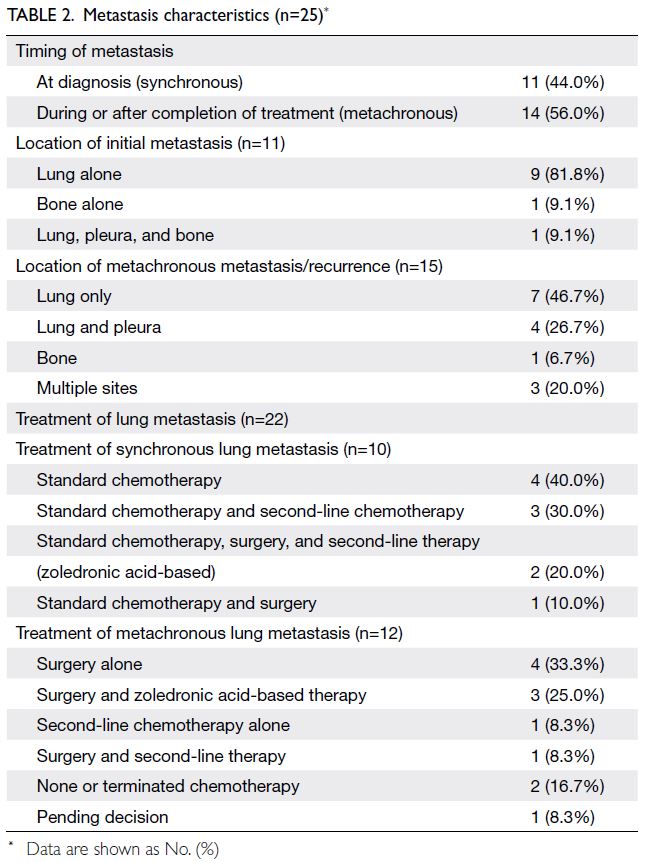

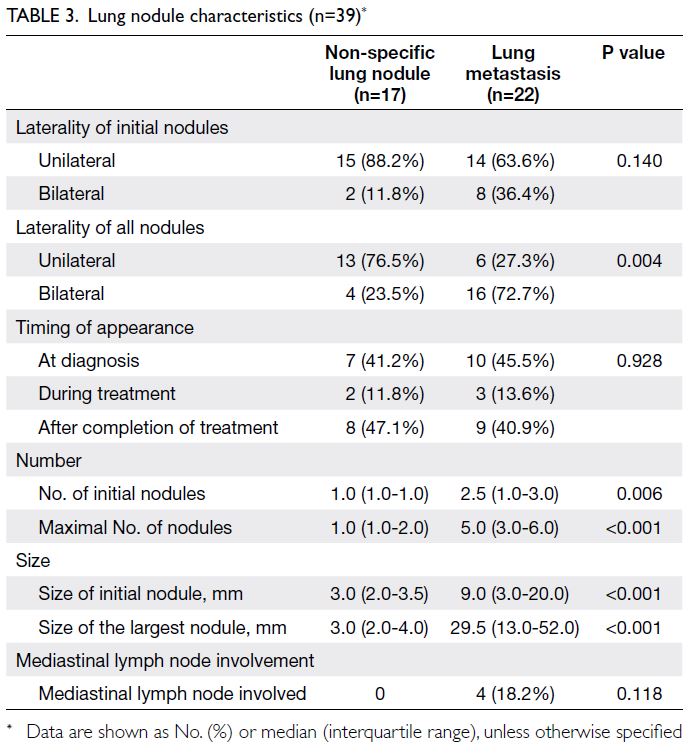

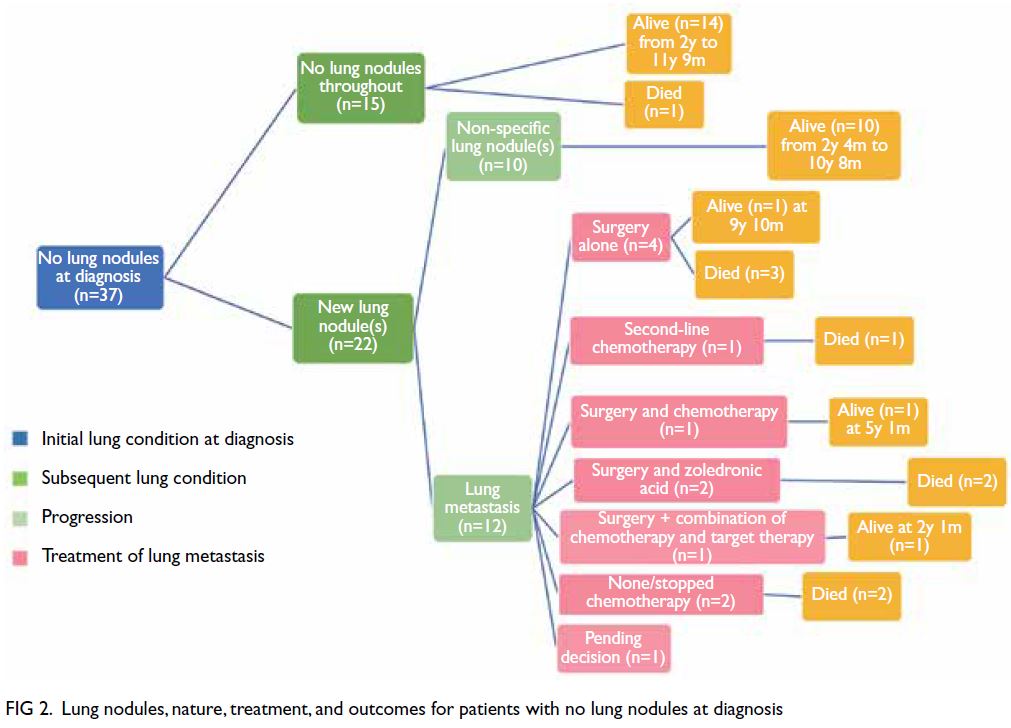

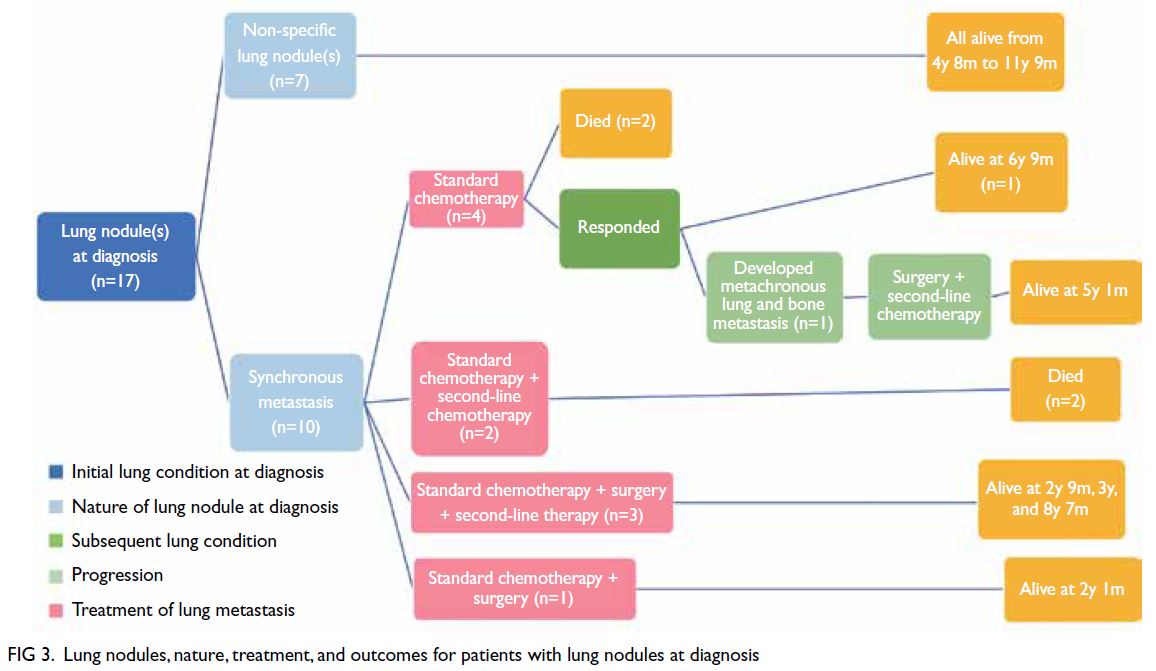

Table. Baseline characteristics and follow-up results of patients who underwent unilateral or bilateral cataract extraction and primary intraocular lens implantation before the age of 1 year

Figure 1. Magnitude of myopic shift per year from 1 to 10 years postoperatively, and between 10 years postoperatively and last follow-up, after primary implantation of intraocular lens in infants aged <1 year. Boxes: quartile 1 to quartile 3 (interquartile range). Lines: medians. Whiskers: maximum and minimum values excluding potential outliers and extreme values. Circles: potential outliers, more than 1.5 interquartile ranges but at most 3 interquartile ranges below quartile 1 or above quartile 3. Asterisks: extreme values, more than 3 interquartile ranges below quartile 1 or above quartile 3

Figure 2. Spherical equivalent refraction immediately after operation, at 1 year to 10 years, and at last follow-up after primary intraocular lens implantation in infants aged <1 year. Boxes: quartile 1 to quartile 3 (interquartile range). Lines: medians. Whiskers: maximum and minimum values excluding potential outliers and extreme values. Circles: potential outliers, more than 1.5 interquartile ranges but at most 3 interquartile ranges below quartile 1 or above quartile 3

Factors affecting myopic shift at 1 year and at

10 years

In univariate analysis, a larger myopic shift at 1 year postoperatively was correlated with younger age

at operation (R2=0.585, P=0.004), more hyperopic

immediate postoperative refraction (R2=-0.533,

P=0.011), and a need for secondary posterior

capsulotomy (U=20, z=-2.066, P=0.04). One-year myopic shift was not correlated with initial axial

length (R2=0.038, P=0.878), and it did not differ

between unilateral (median=-5.81 D) and bilateral

cases (median=-4.38 D) [U=41.5, z=0.469, P=0.652].

Multiple linear regression was performed for

statistically significant factors identified during

univariate analysis. Only age at operation remained

statistically significant (P=0.025); immediate

postoperative refraction (P=0.191) and a need for

secondary posterior capsulotomy (P=0.781) were

not significant in multivariate analysis.

The total amount of myopic shift at 10 years

postoperatively was correlated with age at operation

(R2=0.579, P=0.006), but it was not correlated with

immediate postoperative refraction (R2=-0.339,

P=0.133) or initial axial length (R2=0.291, P=0.241).

There was no difference in the amount of myopic

shift at 10 years between unilateral (median=-14.62

D) and bilateral cases (median=-10.50 D) [U=40.5,

z=1.357, P=0.185] or between eyes that required

secondary posterior capsulotomy (median=-11.25

D) and eyes that did not (median = -6.19 D) [U=24,

z=-1.645, P=0.112].

Factors affecting spherical equivalent refraction at 1 year and at 10 years

Spherical equivalent refraction at 1 year did

not significantly differ between unilateral

(median=-2.69 D) and bilateral cases

(median=+1.13 D) [U=59, z=1.959, P=0.053]

or between eyes that required secondary

capsulotomy (median=+0.31 D) and eyes that

did not (median=+1.42 D) [U=32.5, z=-1.143,

P=0.261]. Partial correlation analysis showed that

after adjustment for age at operation, immediate

postoperative refraction (R2=0.522, P=0.015) was a

statistically significant predictor of SER at 1 year.

In contrast, SER at 10 years postoperatively

was significantly more myopic in unilateral

cases (median=-10.63 D) than in bilateral cases

(median=-4.81 D) [U=49.5, z=2.264, P=0.017]. This

finding may be related to surgeon preference for

less hyperopic target refractions in unilateral cases,

which can match the refraction of the fellow eye

and potentially prevent significant postoperative

anisometropia. Indeed, after adjustment for age,

immediate postoperative SER was significantly

less hyperopic in unilateral cases than in bilateral

cases (P=0.025). A need for secondary posterior

capsulotomy (U=28, z=-1.325, P=0.205) was not

correlated with SER at 10 years. After adjustment

for laterality, both age at operation (P=0.066) and

immediate postoperative refraction (P=0.116) were

not statistically significant predictors of SER at 10

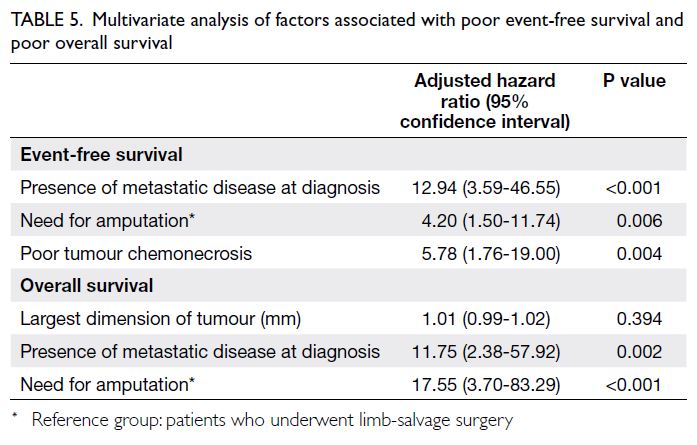

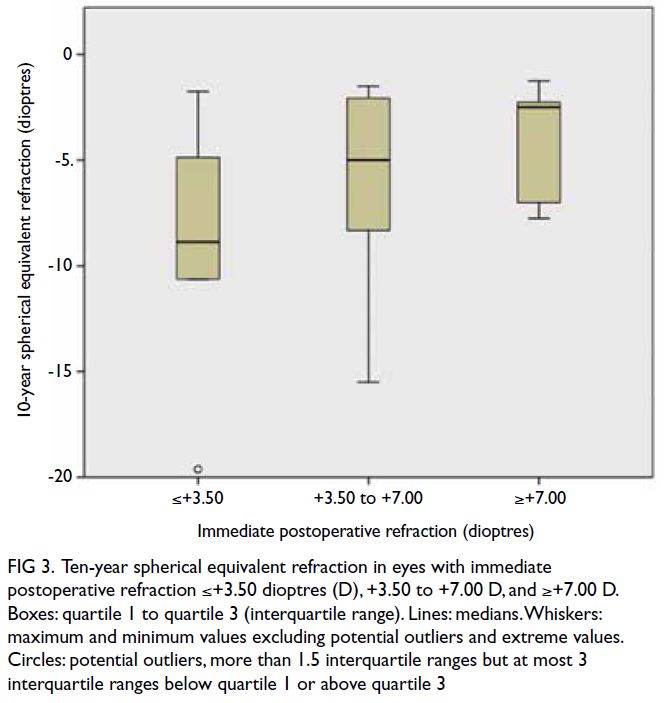

years. There was no significant difference in 10-year

SER among eyes with immediate postoperative

refraction ≤+3.50 D, +3.50 to +7.00 D, and ≥+7.00 D

(P=0.439), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Ten-year spherical equivalent refraction in eyes with immediate postoperative refraction ≤+3.50 dioptres (D), +3.50 to +7.00 D, and ≥+7.00 D. Boxes: quartile 1 to quartile 3 (interquartile range). Lines: medians. Whiskers: maximum and minimum values excluding potential outliers and extreme values. Circles: potential outliers, more than 1.5 interquartile ranges but at most 3 interquartile ranges below quartile 1 or above quartile 3

Subgroup analysis was performed for bilateral

cases only. Multiple regression analysis showed

that at 1 year, both age at operation (P=0.014) and

immediate postoperative refraction (P=0.024)

remained significant predictors of SER after

unilateral cases had been excluded. At 10 years

postoperatively, age at operation was a significant

predictor of SER (P=0.015), whereas immediate

postoperative refraction was not (P=0.135).

Axial length and keratometry

Mean preoperative axial length was 19.12 mm,

whereas mean axial length at 10 years was 24.82 mm.

There were no differences in initial axial length

(U=32, z=0.894, P=0.421) or total axial length change

(U=22, z=-0.224, P=0.875) between unilateral and

bilateral cases. Final axial length was significantly

greater than preoperative axial length (z=3.823,

P<0.0005). Total axial length change was strongly

correlated with total myopic shift (R2=-0.791,

P<0.0005). There was no difference between

preoperative and final keratometry values (z=0.081,

P=0.936). The total change in the mean keratometry

value was not correlated with total myopic shift

(R2=-0.168, P=0.490).

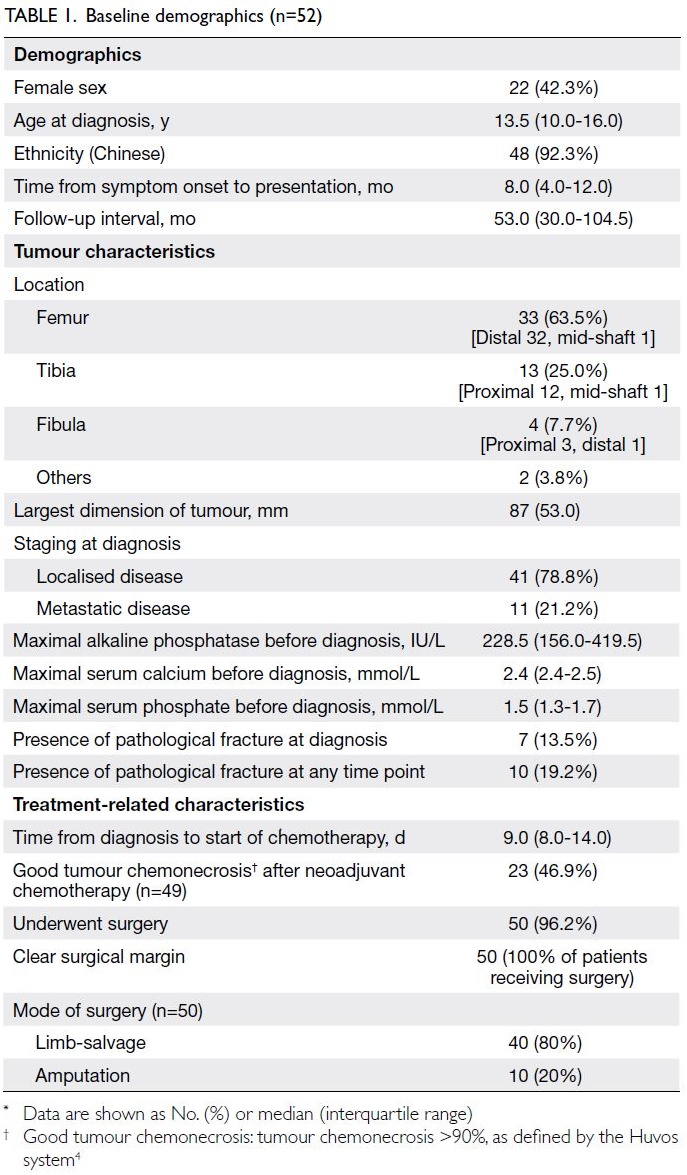

Final best-corrected visual acuity

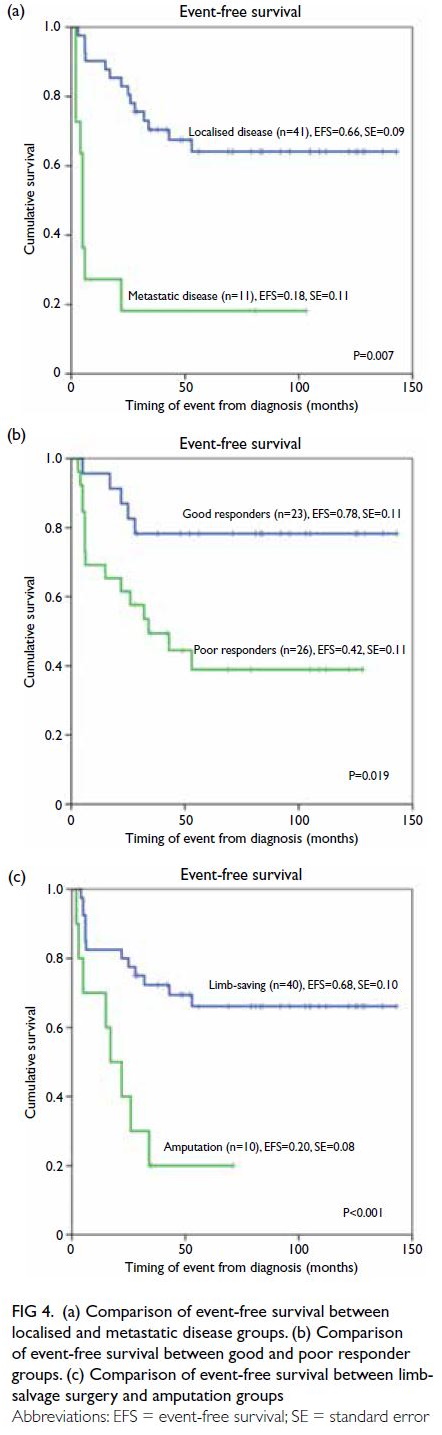

At the last follow-up, 11 eyes (50%) had a final BCVA

of 0.18 logMAR or better, six eyes (27%) had moderate

amblyopia with BCVA of 0.3 to 0.6 logMAR, and five

eyes (23%) had severe amblyopia with BCVA of 0.7

to 1.0 logMAR. There was a statistically significant

correlation between immediate postoperative

refraction and final BCVA (R2=0.440, P=0.041).

Best-corrected visual acuity was worse in eyes that

required secondary capsulotomy (U=74.5, z=1.995,

P=0.049). Multiple regression revealed that a need for

secondary capsulotomy was no longer a significant

predictor for BCVA (P=0.299), whereas immediate

postoperative refraction remained a significant

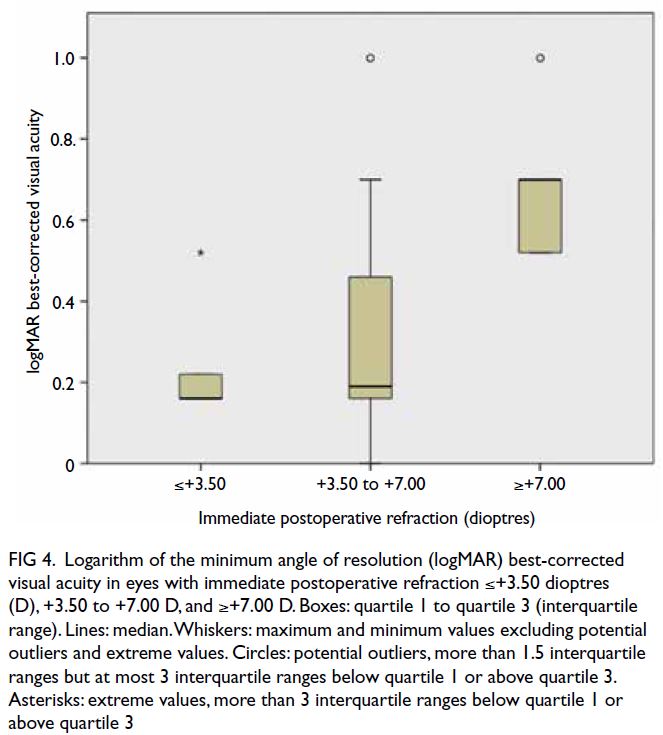

predictor for BCVA (P=0.018). Best-corrected

visual acuity was significantly worse in eyes with

immediate postoperative refraction of +7.00 D or

higher than in eyes with lower levels of immediate

postoperative hyperopia (P=0.029) [Fig 4]. There

were no significant correlations of final BCVA with

age at operation (R2=-0.041, P=0.856), SER at 10

years (R2=0.011, P=0.963), SER at last follow-up

(R2=-0.122, P=0.589), or laterality (U=48.5, z=-1.087,

P=0.300).

Figure 4. Logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) best-corrected visual acuity in eyes with immediate postoperative refraction ≤+3.50 dioptres (D), +3.50 to +7.00 D, and ≥+7.00 D. Boxes: quartile 1 to quartile 3 (interquartile range). Lines: median. Whiskers: maximum and minimum values excluding potential outliers and extreme values. Circles: potential outliers, more than 1.5 interquartile ranges but at most 3 interquartile ranges below quartile 1 or above quartile 3. Asterisks: extreme values, more than 3 interquartile ranges below quartile 1 or above quartile 3

Complications and re-operations

Seventeen eyes underwent 21 re-operations in total, 17 of which were secondary posterior capsulotomies.

All nine eyes that did not undergo primary posterior

capsulorhexis and anterior vitrectomy required

secondary capsulotomy; one of the nine eyes required

secondary capsulotomy twice. Seven of 13 eyes with primary posterior capsulorhexis and anterior

vitrectomy required secondary capsulotomy. Three

eyes underwent injection of intracameral tissue

plasminogen activator, one eye underwent dissection

of fibrinous membrane, and one eye required

removal of anterior capsular phimosis. Notably,

anterior capsular phimosis did not develop in any

other eyes. One eye developed secondary glaucoma

and was excluded from this study.

Discussion

Two important goals in the management of congenital

cataract include achievement of good long-term

visual acuity and minimisation of refractive error

in adulthood. This study focused on long-term

outcomes after primary IOL implantation in infants,

all of whom had ≥10 years of follow-up. Myopic

shift was present in all eyes, and its magnitude

considerably varied. Immediate postoperative

refraction was not a statistically significant predictor

of SER at 10 years. Moreover, there was a statistically

significant negative correlation between immediate

postoperative refraction and final BCVA. Finally,

immediate postoperative refraction of +7.00 D or

higher was correlated with worse final BCVA.

Refractive change in a growing eye

Refractive change in a normal growing eye involves a

complex interaction among axial length elongation,

corneal curvature flattening, and the reduction of

crystalline lens power.14 Additional effects on ocular

growth (eg, related to the presence or laterality

of congenital cataract, age at corrective surgery,

initial axial length, postoperative visual input, and

compliance with postoperative amblyopia therapy)

remain uncertain.15 The presence of an intraocular

lens magnifies myopic shift in a growing eye—the intraocular lens exhibits constant power and

moves anteriorly away from the retina during ocular

growth, hindering the extrapolation of data from

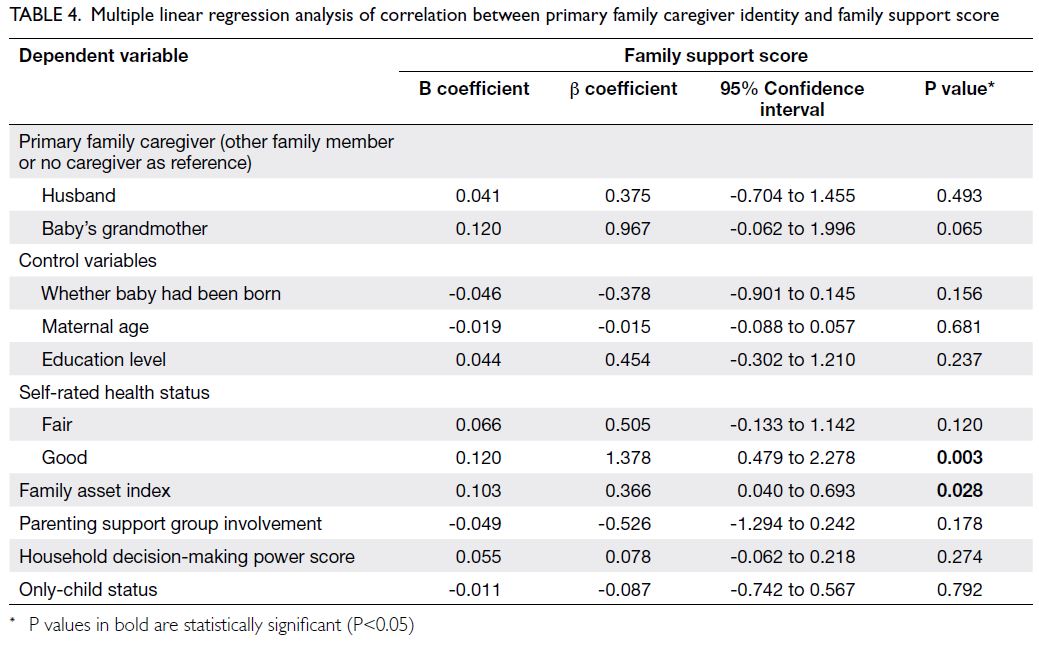

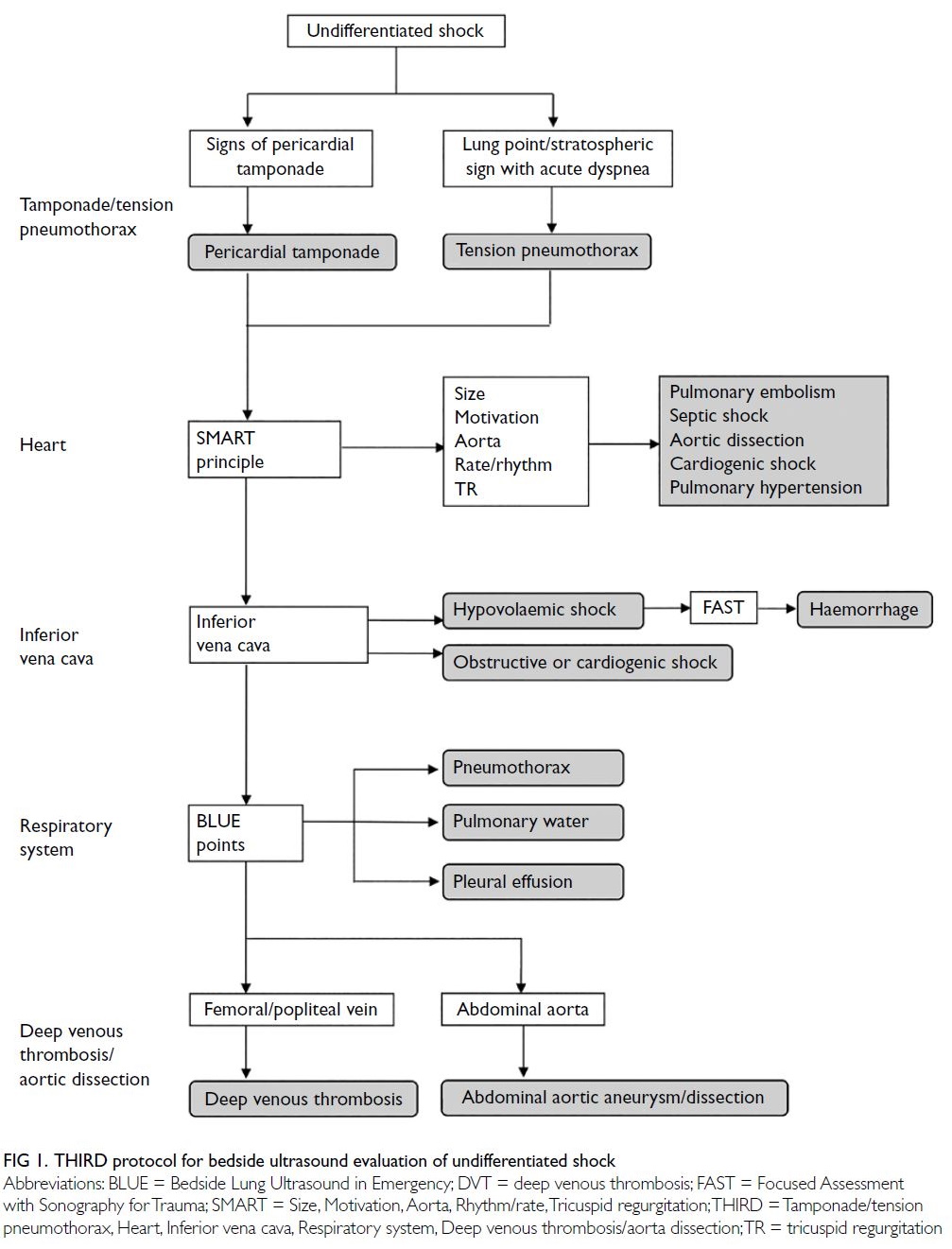

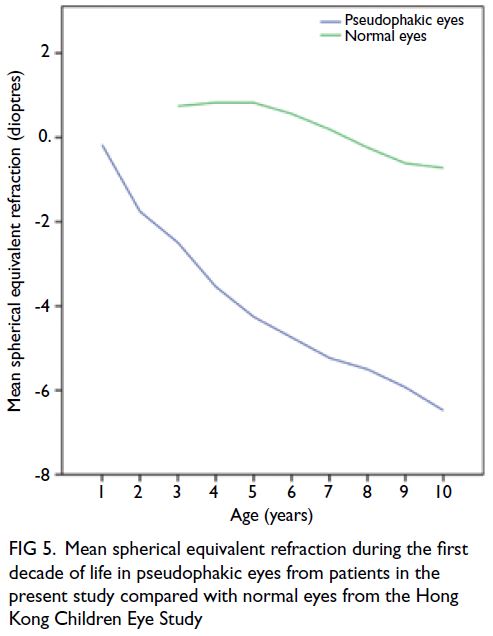

phakic eyes.5 Figure 5 shows the mean SER during

the first decade of life in pseudophakic eyes from

patients in the present study, compared with normal

eyes from the ongoing population-based Hong Kong

Children Eye Study.16 At 10 years after corrective

surgery, the mean SER was -6.48 D in pseudophakic

eyes, whereas it was -0.72 D in normal eyes of age-matched

children. The mean axial length at 10 years

was 24.82 mm in pseudophakic eyes, whereas it was

23.79 mm in normal eyes of age-matched children.16

These data imply the presence of a greater myopic

shift and greater increase in axial length among

pseudophakic eyes which continues beyond the first

2 years of life; notably, these increases are relative

to the mean growth of normal eyes in Hong Kong

children, who exhibit a higher prevalence of myopia

compared with other populations.16

Figure 5. Mean spherical equivalent refraction during the first decade of life in pseudophakic eyes from patients in the present study compared with normal eyes from the Hong Kong Children Eye Study

Refractive change after primary intraocular

lens implantation in infants

Several other studies of myopic shift have revealed

considerable refractive change after primary IOL

implantation in infants aged <1 year. At 5 years

postoperatively, the Infant Aphakia Treatment

Study revealed a mean myopic shift of -8.97 D for

infants surgically treated at the age of 1 month and

-7.22 D for infants surgically treated at the age of

6 months,9 whereas Negalur et al17 found a median

myopic shift of -8.43 D after the same duration of

follow-up in infants operated before the age of

6 months. Fan et al18 reported a mean myopic shift

of -7.11 D at 3 years postoperatively in infants

operated before the age of 1 year; Lu et al19 reported

a mean myopic shift of -6.46 D at 2 years in 22 eyes,

as well as a mean myopic shift of -8.67 D at 6 years

in three eyes, among infants operated between the

age of 6 and 12 months. In our study, which had a

longer follow-up period, the mean 10-year myopic

shift was -11.62 ± 5.14 D and myopic progression

continued beyond 10 years postoperatively. These

findings highlight the importance of using long-term

data to guide management decisions, including the

selection of target refraction and the determination

of appropriate timing for enhancement procedures

(eg, IOL exchange).

Our results showed that myopic shift was

greatest in the first postoperative year and was correlated with age at operation, which is consistent

with findings in the literature.9 10 17 18 19 20 21 Because age

at operation is most frequently associated with the

magnitude of refractive change, many surgeons

prefer to adjust initial hyperopia according to age.

McClatchey et al22 recommended targets of +5.00

to +8.00 D in infants aged <1 year, whereas Valera

Cornejo et al4 selected targets of +7.00 to +9.00 D in

infants of the same age-group. The results of the Infant

Aphakia Treatment Study suggested that, to achieve

emmetropia at 5 years, immediate postoperative

hyperopia should be +10.50 D from 4 to 6 weeks of

age and +8.50 D from 7 weeks to 6 months of age.9

However, our results showed considerable variation

in myopic shift at 10 years (range, -21.88 to -3.75 D);

after adjustment for age, immediate postoperative

refraction was not a statistically significant predictor

of SER at 10 years. Other studies have shown that

initial refraction and IOL undercorrection were not

significantly associated with the magnitude or rate

of myopic shift9 18 22 23; they also revealed large and

unpredictable variations in refractive outcomes

after IOL implantation in young infants.10 20 21 22 24 25

At the 3-year follow-up, refractive change ranged

from +2.00 to -15.50 D in a study by Gouws et al26

and from -0.47 to -10.69 D in a study by Fan et al.18

Although we observed a trend towards more myopic

10-year refractions in groups with lower initial

postoperative hyperopia, there were no significant

differences because of substantial variability in the

data (Fig 3). The Infant Aphakia Treatment Study

showed that the actual and expected amounts

of myopic shift differed in a large percentage of

patients; 50% of patients exhibited differences of

+3.00 to +14.00 D from expected values.9 Therefore,

age-adjusted suggested targets only compensate for

the mean expected myopic shift; large interpatient

variability will often result in unanticipated long-term

outcomes for individual patients. Correlation

analysis in our study revealed that age at operation

only explained 58% of the variance in myopic shift at

10 years. This correlation is presumably influenced by

other factors that contribute to myopic progression,

such as genetics, ethnicity, outdoor exposure,

education level, and extent of near work.27

Long-term best-corrected visual acuity

The achievement of optimal long-term BCVA

is another important goal of surgical treatment

for congenital cataract. In our study, immediate

postoperative refraction of ≥+7.00 D was correlated

with worse BCVA. Similarly, in a study of infants

who underwent surgery between the ages of 2 and

21 months, with ≥4 years of follow-up, Magli et al10

found that BCVA was higher in infants with initial

spherical refraction between +1.00 and +3.00 D than

in infants with initial spherical refraction >+3.00 D.

In a study that included older children who underwent surgery at or before the age of 8.5 years,

Lowery et al11 found that low early postoperative

hyperopia (+1.75 to +5.00 D) yielded better longterm

BCVA, compared with refractions <+1.75

or >+5.00 D in unilateral cases; no difference was

observed in bilateral cases. Another study of older

children (surgically treated between the ages of

2 and 6 years) revealed no difference in BCVA

between initial postoperative refractive errors of

near emmetropia versus undercorrection of +2.00

to +5.50 D23; no patients had initial refraction values

>+5.50 D. High initial postoperative hyperopia

requires good compliance with refractive correction;

in infants, such hyperopia also requires amblyopia

treatment because younger children are at higher

risk of developing amblyopia. Hyperopia is more

amblyogenic than myopia because young children

have higher demands for near vision28; moreover,

hyperopia causes defocusing in both distance and

near vision, particularly among patients who exhibit

pseudophakia related to accommodation loss.

Studies have shown variable compliance with optical

correction and amblyopia treatment after congenital

cataract surgery19 29; the use of high-plus spectacles

is associated with various optical aberrations.

Additionally, contact lenses are suboptimal

because one of the original aims of intraocular lens

implantation is to avoid the need for contact lens.

Myopia is comparatively less amblyogenic because

it allows retention of near vision, particularly if

the amount of myopia remains low until later

in childhood when visual development is more

mature.30 Therefore, parental motivation and the

likelihood of compliance should be included in

decisions regarding postoperative refraction. Ideally,

high myopia in adulthood should be minimised.

However, this goal should be balanced with the risks

of amblyopia and long-term poor vision. Therefore,

the selection of high hyperopia (>+7.00 D) as an

initial postoperative target refraction should be

avoided when possible.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of our study was the long follow-up period. Additionally, it only included infants who

underwent IOL implantation before the age of 1 year

because the refractive change in this group exhibits

the greatest variability and is most challenging to

predict.5

There were some limitations in this study. First,

it used a retrospective design and included a small

number of patients. Second, there was no objective

monitoring of compliance with optical correction or

amblyopia treatment. Third, few unilateral cases were

included, which may have hindered the detection

of larger myopic shifts in post–IOL implantation

in unilateral cases. Notably, some previous studies

revealed larger myopic shifts after IOL implantation in such cases.4 17 21 22

In conclusion, the large and variable refractive

change after IOL implantation in infants aged <1

year hinders the prediction of long-term refractive

outcomes in individual patients. When selecting

target refraction in infants, low to moderate

hyperopia (<+7.00 D) should be considered to

balance the avoidance of high myopia in adulthood

with the risk of worse long-term visual acuity related

to high postoperative hyperopia

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JJT Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JJT Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: JJT Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JJT Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JJT Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: JJT Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JC Yam was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central/Kowloon East), Hospital Authority (Ref No.: KC/KE-19-0059/ER-4). The requirement for patient consent was waived by the ethics board due to the retrospective nature of the study. The

study is conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of

the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

1. Kumar P, Lambert SR. Evaluating the evidence for and against the use of IOLs in infants and young children.

Expert Rev Med Devices 2016;13:381-9. Crossref

2. Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group; Lambert SR,

Lynn MJ, et al. Comparison of contact lens and intraocular

lens correction of monocular aphakia during infancy: a

randomized clinical trial of HOTV optotype acuity at

age 4.5 years and clinical findings at age 5 years. JAMA

Ophthalmol 2014;132:676-82. Crossref

3. Lambert SR, Aakalu VK, Hutchinson AK, et al. Intraocular

lens implantation during early childhood: a report by the

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology

2019;126:1454-61. Crossref

4. Valera Cornejo DA, Flores Boza A. Relationship between

preoperative axial length and myopic shift over 3 years after

congenital cataract surgery with primary intraocular lens

implantation at the National Institute of Ophthalmology of

Peru, 2007-2011. Clin Ophthalmol 2018;12:395-9. Crossref

5. McClatchey SK, Parks MM. Theoretic refractive changes after lens implantation in childhood. Ophthalmology

1997;104:1744-51. Crossref

6. Enyedi LB, Peterseim MW, Freedman SF, Buckley EG. Refractive changes after pediatric intraocular lens

implantation. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:772-81. Crossref

7. Astle WF, Ingram AD, Isaza GM, Echeverri P. Paediatric pseudophakia: analysis of intraocular lens power and myopic shift. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2007;35:244-51. Crossref

8. Yam JC, Wu PK, Ko ST, Wong US, Chan CW. Refractive changes after pediatric intraocular lens implantation in

Hong Kong children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus

2012;49:308-13.

9. Weakley DR Jr, Lynn MJ, Dubois L, et al. Myopic shift 5 years after intraocular lens implantation in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. Ophthalmology 2017;124:822-7. Crossref

10. Magli A, Forte R, Carelli R, Rombetto L, Magli G. Long-term outcomes of primary intraocular lens implantation for unilateral congenital cataract. Semin Ophthalmol

2015;31:1-6. Crossref

11. Lowery RS, Nick TG, Shelton JB, Warner D, Green T. Long-term

visual acuity and initial postoperative refractive error

in pediatric pseudophakia. Can J Ophthalmol 2011;46:143-7. Crossref

12. Vasavada A, Chauhan H. Intraocular lens implantation in infants with congenital cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg 1994;20:592-8. Crossref

13. Plager DA, Yang S, Neely D, Sprunger D, Sondhi N. Complications in the first year following cataract surgery with and without IOL in infants and older children. J

AAPOS 2002;6:9-14. Crossref

14. Gordon RA, Donzis PB. Refractive development of the human eye. Arch Ophthalmol 1985;103:785-9. Crossref

15. Indaram M, VanderVeen DK. Postoperative refractive

errors following pediatric cataract extraction with

intraocular lens implantation. Semin Ophthalmol

2018;33:51-8. Crossref

16. Yam JC, Tang SM, Kam KW, et al. High prevalence of

myopia in children and their parents in Hong Kong

Chinese population: the Hong Kong Children Eye Study.

Acta Ophthalmol 2020;98:e639-48. Crossref

17. Negalur M, Sachdeva V, Neriyanuri S, Ali M, Kekunnaya R.

Long-term outcomes following primary intraocular lens

implantation in infants younger than 6 months. Indian J

Ophthalmol 2018;66:1088-93. Crossref

18. Fan DS, Rao SK, Yu CB, Wong CY, Lam DS. Changes in

refraction and ocular dimensions after cataract surgery

and primary intraocular lens implantation in infants. J

Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:1104-8. Crossref

19. Lu Y, Ji YH, Luo Y, Jiang YX, Wang M, Chen X. Visual

results and complications of primary intraocular lens

implantation in infants aged 6 to 12 months. Graefes Arch

Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010;248:681-6. Crossref

20. O’Keefe M, Fenton S, Lanigan B. Visual outcomes and

complications of posterior chamber intraocular lens

implantation in the first year of life. J Cataract Refract Surg

2001;27:2006-11. Crossref

21. Hoevenaars NE, Polling JR, Wolfs RC. Prediction error and myopic shift after intraocular lens implantation in paediatric cataract patients. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:1082-5. Crossref

22. McClatchey SK, Dahan E, Maselli E, et al. A comparison of the rate of refractive growth in pediatric aphakic and pseudophakic eyes. Ophthalmology 2000;107:118-22. Crossref

23. Lambert SR, Archer SM, Wilson ME, Trivedi RH, del Monte

MA, Lynn M. Long-term outcomes of undercorrection

versus full correction after unilateral intraocular lens

implantation in children. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153:602-8.e1. Crossref

24. Barry JS, Ewings P, Gibbon C, Quinn AG. Refractive outcomes after cataract surgery with primary lens

implantation in infants. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:1386-9. Crossref

25. Plager DA, Kipfer H, Sprunger DT, Sondhi N, Neely DE. Refractive change in pediatric pseudophakia: 6-year

follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:810-5. Crossref

26. Gouws P, Hussin HM, Markham RH. Long term results of primary posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation for congenital cataract in the first year of life. Br J

Ophthalmol 2006;90:975-8. Crossref

27. Morgan IG, French AN, Ashby RS, et al. The epidemics

of myopia: aetiology and prevention. Prog Retin Eye Res

2018;62:134-49. Crossref

28. Pascual M, Huang J, Maguire MG, et al. Risk factors for amblyopia in the vision in preschoolers study.

Ophthalmology 2014;121:622-9.e1. Crossref

29. Drews-Botsch CD, Hartmann EE, Celano M, Infant

Aphakia Treatment Study Group. Predictors of adherence

to occlusion therapy 3 months after cataract extraction in

the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study. J AAPOS 2012;16:150-5. Crossref

30. O’Hara MA. Pediatric intraocular lens power calculations. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2012;23:388-93. Crossref