© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Epidemiology and outcomes of geriatric and

non-geriatric patients with drug allergy labels in Hong Kong

Philip H Li, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine); HY Chung, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine); CS Lau, MD, FRCP

Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Philip H Li (liphilip@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Adverse drug reactions are more

common in geriatric patients than in younger

patients, but there have been insufficient studies

concerning the epidemiology or burden of drug

allergy labels in geriatric patients. We prospectively

investigated the prevalence and outcomes of

geriatric patients with drug allergy labels in a cohort

of hospitalised patients.

Methods: Patients admitted to a regional hospital

over a 6-month period were recruited for this

study. All patients with drug allergy labels were

prospectively followed until discharge; clinical data

were anonymously extracted for analyses. Patients

were categorised into either geriatric (aged ≥65

years) or non-geriatric (aged <65 years) groups.

Demographic characteristics, clinical outcomes, and

prevalences of drug allergy labels were compared

between groups.

Results: There were 4361 admissions involving

3641 patients during the 6-month study period.

Overall, 492 patients (13.5%) had drug allergy labels,

consisting of 151 non-geriatric patients (30.7%) and

341 geriatric patients (69.3%). The prevalence of drug

allergy labels did not significantly differ between

geriatric and non-geriatric patients (13.5% vs 13.5%, P=0.976). Significantly more patients in the geriatric

group had drug allergy labels to cardiovascular

system drugs (15.5% vs 4.6%, P=0.001). Geriatric

patients had a significantly lower rate of direct

discharge from the hospital (73.0% vs 88.1%,

P<0.001) and required transfers to convalescent or

rehabilitation care for further management.

Conclusions: More than 13% of hospitalised geriatric

patients had drug allergy labels. The leading causes

of drug allergy labels were similar between geriatric

and non-geriatric patients. Geriatric patients with

drug allergy labels had significantly more labelled

allergies to cardiovascular system drugs and adverse

clinical outcomes.

New knowledge added by this study

- More than 13% of hospitalised geriatric patients in Hong Kong had drug allergy (DA) labels.

- The most common DA labels were similar between geriatric and non-geriatric patients.

- Geriatric patients had significantly more DA labels to cardiovascular drugs and significantly lower direct discharge rates.

- Clinicians should consider the large burden of reported DAs and associated adverse clinical outcomes among hospitalised geriatric patients, particularly with respect to antibiotic therapy and cardiovascular system drugs.

- Geriatric patients with reported DAs should be selectively referred for formal allergy workup to confirm or refute suspected DAs.

Introduction

With the continued increase in life expectancy

worldwide, population ageing is an especially

marked phenomenon in Asian populations.1 It has been estimated that nearly one in three individuals

will be in the geriatric age-group (aged ≥65 years) in

Hong Kong within the next 15 years.2 Unfortunately,

improved longevity is not necessarily linked

with improved health or healthcare. Ageing is an unavoidable process associated with many age-related

diseases. For example, “immunosenescence”—the

age-related dysregulation of the immune system—increases geriatric patients’ susceptibilities to

a myriad of immune-mediated disorders (eg,

infection, malignancy, and autoimmunity) and

adverse reactions to medications.3 4

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are much more

common in geriatric patients, such that they cause significant morbidity and mortality, compared with

younger patients.5 6 Geriatric patients are much more

likely than younger patients to be hospitalised for

ADRs.7 In particular, drug allergies (DAs) comprise

approximately 6% to 10% of all ADRs and up to

10% of the resulting fatal reactions.6 Despite the

severe consequences of genuine DAs, many patients

mistakenly report non-immune-mediated ADRs as

“allergies”. For example, almost 90% of patients with

beta-lactam DA labels were confirmed not to be

genuinely allergic in previous studies, although such

incorrect DA labels were associated with a multitude

of dire clinical consequences.8 9 10 11 12 To the best of our

knowledge, although the prevalence of ADRs has

been extensively reported in geriatric populations,

there have been no adequate studies concerning

the epidemiology or burden of DAs in geriatric

patients.13 To address this lack of information, we

performed a prospective analysis of the prevalence

and outcomes of geriatric patients with DA labels in

a cohort of hospitalised patients in Hong Kong.

Methods

All patients admitted to the acute general medical

wards of Queen Mary Hospital from 1 July 2018 to

31 December 2018 were recruited for this study. The

Queen Mary Hospital is the only public hospital in the

Hong Kong West Cluster, which serves a population

of 0.5 million and provides acute medical admissions

through its Accident and Emergency Department.

After admission, patients may be transferred to

other convalescent or rehabilitation units of the

Hong Kong West Cluster for further management if

deemed unfit for direct discharge from the hospital.

Patient age and sex were recorded, as was the

presence of DA labels. All patients with DA labels

were then followed until discharge; clinical data

were anonymously extracted for analyses. Extracted

clinical data included patient age and sex, presence

and details of DA labels, length of stay (from the day

of admission to the day of discharge [including stay

at convalescent or rehabilitation hospitals] or death),

and discharge outcomes (direct discharge, transfer to

another hospital, or death). Details of DA labels were

reviewed to ensure that the reported manifestations

were consistent with the presence of clinical allergies

(ie, immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions).

Manifestations suggestive of other non-immune-mediated

ADRs were excluded.

The DA labels were categorised in accordance

with the British National Formulary classifications (if

available): beta-lactam antibiotics (5.1.1 Penicillins

and 5.1.2 Cephalosporins and other beta-lactams),

non-beta-lactam antibiotics (5.1 Antibacterial

drugs, other than 5.1.1 and 5.1.2), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (10.1.1 NSAIDs), cardiovascular

system (CVS) medications (2 CVS), intravenous

contrast media, allopurinol, opioid analgesic (4.7.2 Opioid analgesics), non-opioid analgesics (4.7.1.

Non-opioid analgesics and compound prep),

antihistamines (3.4.1 Antihistamines), antifungals

(5.2 Antifungal drugs), or others. Patients were

categorised into either geriatric (aged ≥65 years) or

non-geriatric (aged <65 years) groups. Demographic

characteristics, clinical outcomes, and prevalences

of DA labels were compared between groups.

The Chi squared test and independent samples

t tests were respectively used to compare categorical

and continuous variables between groups in

univariate analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant for the multivariate analysis.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 20.0; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], Untied States) was used for all

analyses. The study protocol was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong

Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

Results

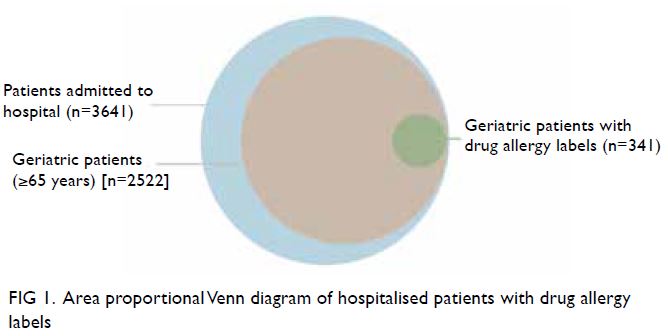

There were 4361 admissions involving 3641 patients during the 6-month study period. The male-to-female

ratio was 1:1.2. In total, 2522 patients (69.3%)

were included in the geriatric group, with mean age

71.56±17.3 years.

In total, 492 patients (13.5%) had DA labels,

consisting of 151 non-geriatric patients (30.7%) and

341 geriatric patients (69.3%) [Fig 1].

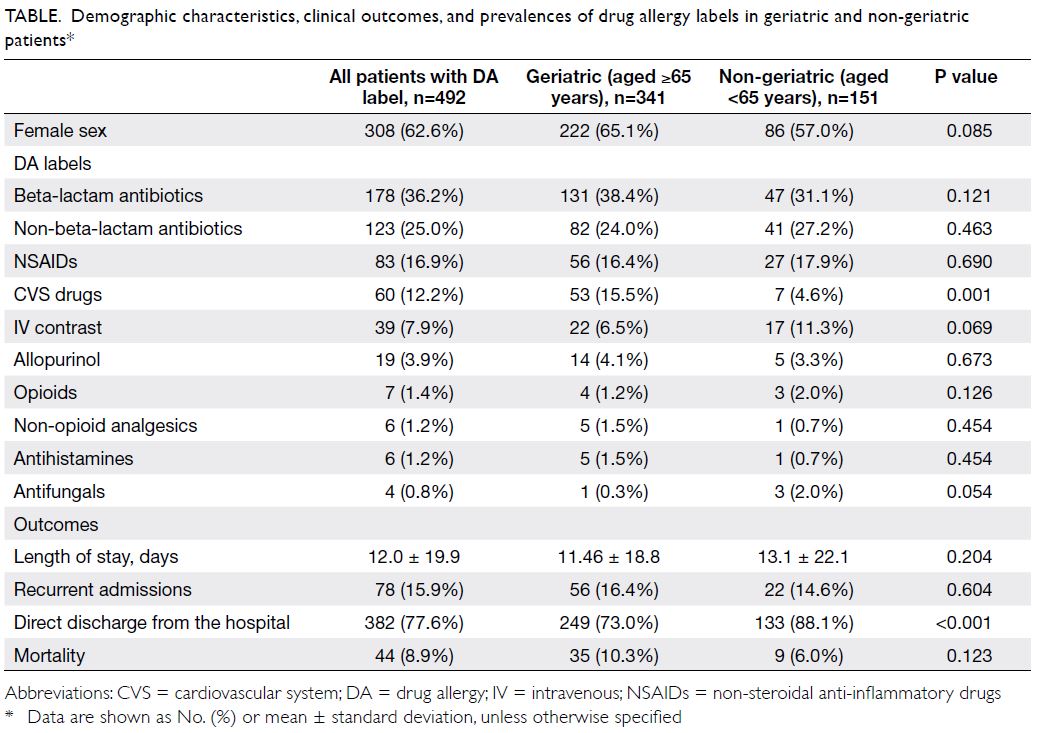

The overall prevalence of DA labels did not significantly differ between geriatric and non-geriatric

patients (13.5% [341/2522] vs 13.5%

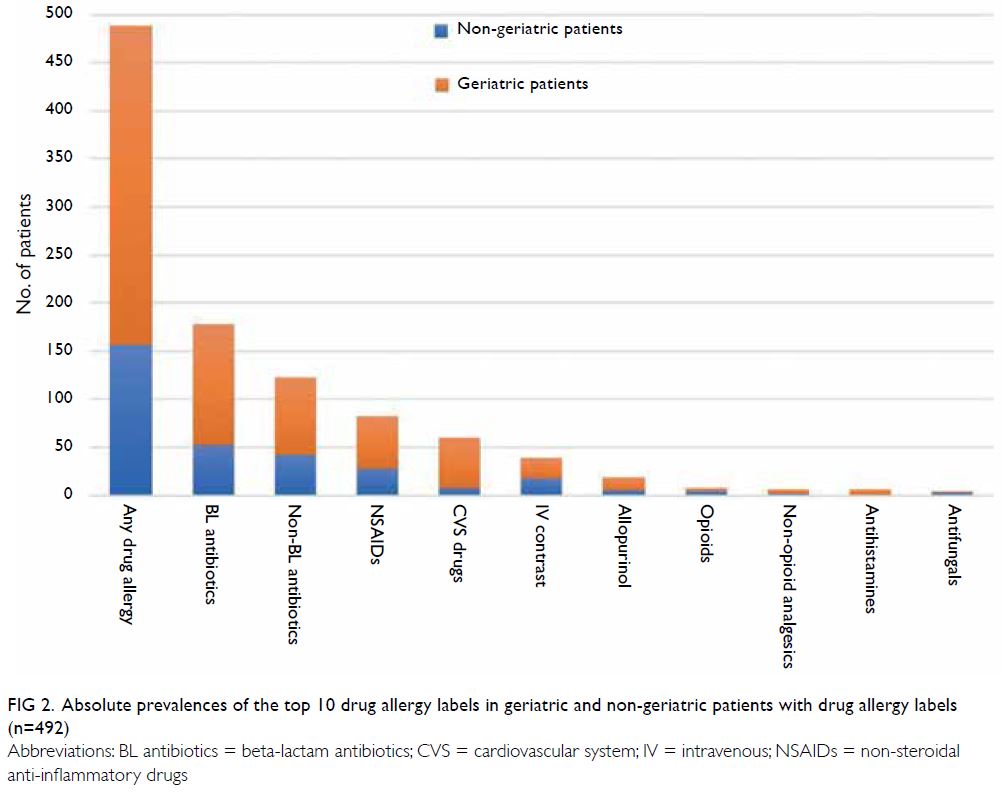

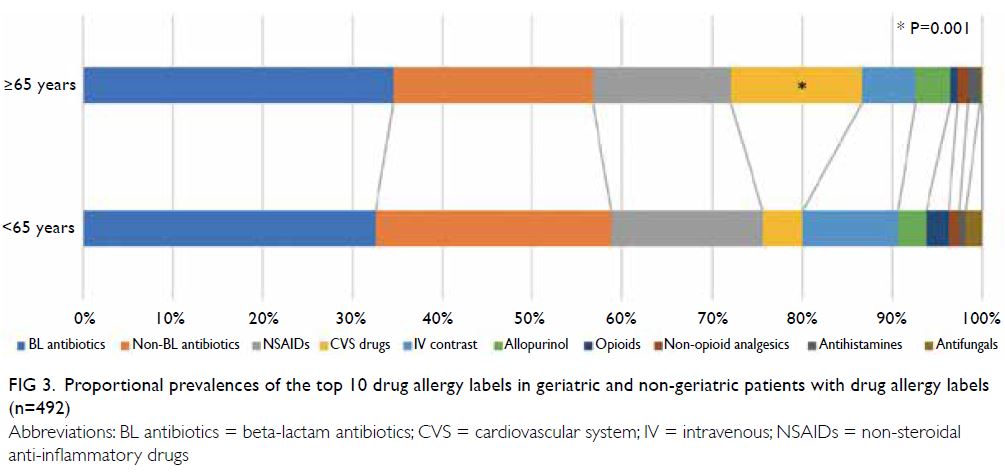

[151/1119], P=0.976) [Table]. The absolute and

proportional prevalences of the top 10 categories

of DA labels (in descending order) for geriatric and

non-geriatric patients are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Table. Demographic characteristics, clinical outcomes, and prevalences of drug allergy labels in geriatric and non-geriatric patients

Figure 2. Absolute prevalences of the top 10 drug allergy labels in geriatric and non-geriatric patients with drug allergy labels (n=492)

Figure 3. Proportional prevalences of the top 10 drug allergy labels in geriatric and non-geriatric patients with drug allergy labels (n=492)

The majority of patients with DA labels were

aged ≥65 years (69.3%, 341/492). The male-to-female

ratio did not significantly differ between

geriatric and non-geriatric groups. Significantly

more patients in the geriatric group had DA labels

to CVS drugs (15.5% vs 4.6%, P=0.001), while the proportions of other DA labels were similar between

the two groups. Patients in the geriatric group had

a significantly lower rate of direct discharge from

the hospital (73.0% vs 88.1%, P<0.001). The absolute

mortality rate tended to be higher among patients

in the geriatric group, but this difference was not

statistically significant (10.3% vs 6.0%, P=0.123).

Discussion

Although the prevalence and consequences of overall

ADRs have been extensively investigated, this is the

first study to specifically examine the epidemiology

and outcomes of geriatric patients with DA labels. In

our cohort, 13.5% of all hospitalised geriatric patients

had DA labels; the leading causes of DA labels were

comparable between geriatric and non-geriatric

patients. Notably, there were significantly more

labelled DAs to CVS medications and significantly

more adverse clinical outcomes in geriatric patients.

Adverse drug reactions are defined as any

“appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction”

to medications which can occur through

various immunological or non-immunological

mechanisms.14 Drug allergies or “hypersensitivity

reactions” comprise type B (non-dose-related)

ADRs, which result from specific immune-mediated

responses to a medication. An important problem is

that many non-immune-mediated ADRs are often clinically misinterpreted or incorrectly recorded as

“allergies”. Although the initial DA reactions may

be immunological, genuine allergies may gradually

wane and warrant re-evaluation. For example, the vast majority of patients with beta-lactam allergies

lose skin testing sensitivity over an interval of

10 years.15 16 Similarly, mild delayed (presumptively

T-cell-mediated) reactions do not consistently recur upon re-exposure.17 18 Often, DA labels present in

the medical records of geriatric patients have not

undergone appropriate allergy testing to verify

whether these labels remain accurate. Geriatric

patients also have had more time and events to

become sensitised or develop ADRs which may

be interpreted as allergies; these labels may not

be entirely correct for some patients. Overall, our

study confirms the presence of the high burden of

DA labels in geriatric patients and corresponding

worse clinical outcomes (ie, significantly lower rate

of direct discharge from the hospital) compared with

non-geriatric patients. This highlights the urgent

need to expand the availability of allergy testing for

this vulnerable population.19 20

As expected, beta-lactam antibiotics

constituted the leading cause of DA labels in both

patient populations in our study (61.5% [131/213]

in the geriatric group and 53.4% [47/88] in the non-geriatric

group). In Hong Kong, the prevalence

of reported beta-lactam antibiotic allergy is

approximately 2% with a cumulative incidence

approaching 10 per 100 000 population.21 Beta-lactam

DA labels are known to have clinically

significant consequences including the use of broad-spectrum

antibiotics, enhanced microbial resistance,

greater number of Clostridium difficile infections,

and expansions of multidrug-resistant organisms.10 11 12

In Hong Kong, Chen et al22 found that the prevalence

of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was

30.1% among older adults living in residential care

homes. The presence of DA labels greatly restricts the

repertoire of first-line antibiotics for such patients.

Beta-lactams remain the most effective first-line

treatment for many bacterial infections including

methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; in

agreement with our findings, the unnecessary use

of alternatives leads to worse patient outcomes,

especially in the vulnerable geriatric population.

Furthermore, we observed a significantly

greater proportion of reported DAs to CVS drugs

among geriatric patients. We postulate that this is

related to the substantially greater burden of CVS

diseases and exposure to CVS drugs in geriatric

patients, compared with other conditions.23 24 As

previously mentioned, although greater exposure

to CVS drugs theoretically increases the risk of

genuine DAs, “allergy” labels could be the result

of incorrectly interpreted ADRs. For example,

the incidences of angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitor treatment–related cough and angioedema

(non-immune-mediated ADRs) increase with age.25

Regardless of their accuracy, this greater proportion

of DA labels to CVS drugs is likely to further restrict

therapeutic options and elicit CVS complications in

geriatric patients. The accuracies of these labels and

their specific effects on CVS complications warrant

dedicated studies in the future.

This study had some important limitations.

First, a higher rate of other adverse clinical outcomes

(such as recurrent admissions and mortality) was

evident among patients in the geriatric group,

although this was not statistically significant. This

trend may have constituted a type II statistical

analysis error due to inadequate sampling and

observational design. Second, we only analysed

geriatric and non-geriatric patients with DA labels,

although geriatric patients may have worse clinical

outcomes regardless of DA status. We were also

unable to analyse individual DAs or manifestations

within the CVS subgroup. Nonetheless, our findings

highlight the vulnerability of this specific geriatric

population and emphasise the need for future

prospective studies. Third, although all DAs were

recorded only after confirmation by the patients’

attending doctors and reported manifestations were

screened by an allergist during data collection, we

were unable to ascertain the accuracy of the DA labels.

Comprehensive evaluations of suspected DAs often

require allergological confirmation with skin and/or

drug provocation tests, which is especially difficult

in frail older adults. A follow-up study to identify

the impacts of genuine allergies and incorrectly

interpreted adverse clinical outcomes is currently in

progress. Lastly, the results of our study were from

a single-centre cohort of hospitalised patients and

allergy records may have been influenced by local

physician practices. Additional multicentre studies,

including patients in the ambulatory setting, are

needed to corroborate the external validity of our

findings.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

report concerning the epidemiology and outcomes

of geriatric patients with DA labels. More than 13%

of hospitalised geriatric patients had DA labels; the

leading causes of reported DAs in these patients

were similar to those of non-geriatric patients in the

same hospital. We also observed significantly more

reported DAs to CVS drugs, as well as worse clinical

outcomes (ie, more frequent transfer to convalescent

or rehabilitation facilities) among patients in the

geriatric group. Additional dedicated studies are

required to confirm the burden and accuracy of

DA labels among the already-vulnerable geriatric

population.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PH Li.

Acquisition of data: PH Li.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PH Li, HY Chung.

Drafting of the manuscript: PH Li, CS Lau.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: PH Li.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PH Li, HY Chung.

Drafting of the manuscript: PH Li, CS Lau.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from HKU/HKW Institutional

Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital

Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB),

Ref UW 18-669.

References

1. Balachandran A, de Beer J, James KS, van Wissen L,

Janssen F. Comparison of population aging in Europe

and Asia using a time-consistent and comparative aging

measure. J Aging Health 2020;32:340-51. Crossref

2. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Hong Kong Population Projections 2015

Available from: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp190.jsp?productCode=B1120015. Accessed 26 May 2020.

3. Pawelec G. Age and immunity: what is “immunosenescence”? Exp Gerontol 2018;105:4-9. Crossref

4. De Martinis M, Sirufo MM, Ginaldi L. Allergy and aging: an old/new emerging health issue. Aging Dis 2017;8:162-75. Crossref

5. Davies EA, O’Mahony MS. Adverse drug reactions in special populations—the elderly. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2015;80:796-807. Crossref

6. Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of

prospective studies. JAMA 1998;279:1200-5. Crossref

7. Muehlberger N, Schneeweiss S, Hasford J. Adverse drug

reaction monitoring—cost and benefit considerations.

Part I: frequency of adverse drug reactions causing hospital

admissions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997;6 Suppl

3:S71-7. Crossref

8. Li PH, Siew LQ, Thomas I, et al. Beta-lactam allergy in

Chinese patients and factors predicting genuine allergy.

World Allergy Organ J 2019;12:100048. Crossref

9. Mattingly TJ 2nd, Fulton A, Lumish RA, et al. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J

Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1649-54.e4. Crossref

10. MacFadden DR, LaDelfa A, Leen J, et al. Impact of reported beta-lactam allergy on inpatient outcomes: a multicenter

prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:904-10. Crossref

11. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious

infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy”

in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:790-6. Crossref

12. Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK.

Risk of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and

Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented

penicillin allergy: population based matched cohort study.

BMJ 2018;361:k2400. Crossref

13. Ventura MT, Scichilone N, Paganelli R, et al. Allergic

diseases in the elderly: biological characteristics and main

immunological and non-immunological mechanisms. Clin

Mol Allergy 2017;15:2. Crossref

14. Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet

2000;356:1255-9. Crossref

15. Trubiano JA, Adkinson NF, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy is not necessarily forever. JAMA 2017;318:82-3. Crossref

16. Blanca M, Romano A, Torres MJ, et al. Update on the evaluation of hypersensitivity reactions to betalactams.

Allergy 2009;64:183-93. Crossref

17. Mori F, Cianferoni A, Barni S, Pucci N, Rossi ME,

Novembre E. Amoxicillin allergy in children: five-day

drug provocation test in the diagnosis of nonimmediate

reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:375-80.e1. Crossref

18. Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, Phillips E. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de-labeling. J Allergy Clin

Immunol Pract 2015;3:365-74.e1. Crossref

19. Chan YT, Ho HK, Lai CK, et al. Allergy in Hong Kong: an unmet need in service provision and training. Hong Kong

Med J 2015;21:52-60. Crossref

20. Lee TH, Leung TF, Wong G, et al. The unmet provision of allergy services in Hong Kong impairs capability for allergy

prevention-implications for the Asia Pacific region. Asian

Pac J Allergy Immunol 2019;37:1-8.

21. Li PH, Yeung HH, Lau CS, Au EY. Prevalence, incidence,

and sensitization profile of beta-lactam antibiotic allergy in

Hong Kong. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e204199. Crossref

22. Chen H, Au KM, Hsu KE, et al. Multidrug-resistant

organism carriage among residents from residential

care homes for the elderly in Hong Kong: a prevalence

survey with stratified cluster sampling. Hong Kong Med J

2018;24:350-60. Crossref

23. Islam MM, Valderas JM, Yen L, Dawda P, Jowsey T, McRae IS. Multimorbidity and comorbidity of chronic

diseases among the senior Australians: prevalence and

patterns. PLoS One 2014;9:e83783. Crossref

24. Morgan TK, Williamson M, Pirotta M, Stewart K, Myers SP, Barnes J. A national census of medicines use: a 24-hour

snapshot of Australians aged 50 years and older. Med J

Aust 2012;196:50-3. Crossref

25. Alharbi FF, Kholod AA, Souverein PC, et al. The impact

of age and sex on the reporting of cough and angioedema

with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors: a case/noncase

study in VigiBase. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2017;31:676-84.Crossref