© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Luxatio erecta of the hip in a 64-year-old man:

a case report

Kemal Gokkus, MD; Mehmet S Sahin, MD

Department of Orthopedics and Trauma, Baskent University Medical Faculty–Alanya Research and Practice Center, Turkey

Corresponding author: Dr Kemal Gokkus (kemalg@baskent.edu.tr)

Case report

In March 2021, a 64-year-old man who was injured

in a fall was brought to our emergency department.

He had lost his balance and fallen while harvesting

avocados from a tree. He reported severe right hip

and right lateral chest pain and was unable to move

his right hip. His vital signs were unremarkable. He

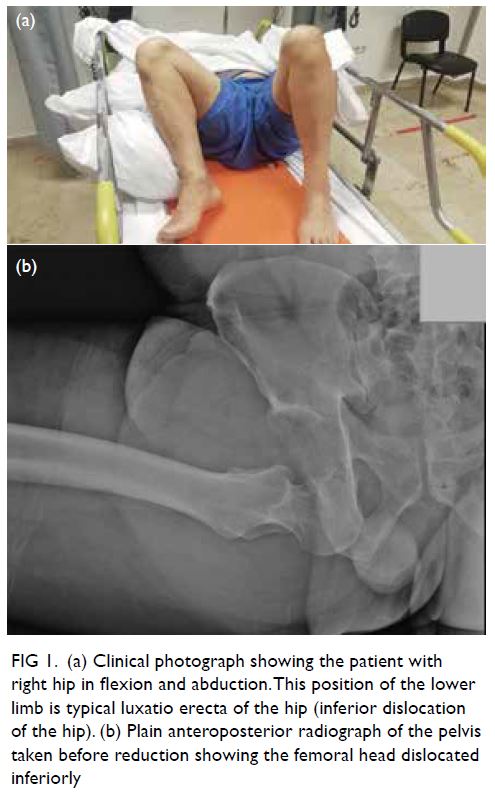

held his right hip in flexion and abduction (Fig 1a).

The limb was neurologically intact and good distal

arterial pulses were present. Plain anteroposterior

radiograph of the pelvis revealed an inferior

dislocation of the femoral head (Fig 1b).

Figure 1. (a) Clinical photograph showing the patient with right hip in flexion and abduction. This position of the lower limb is typical luxatio erecta of the hip (inferior dislocation of the hip). (b) Plain anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis taken before reduction showing the femoral head dislocated inferiorly

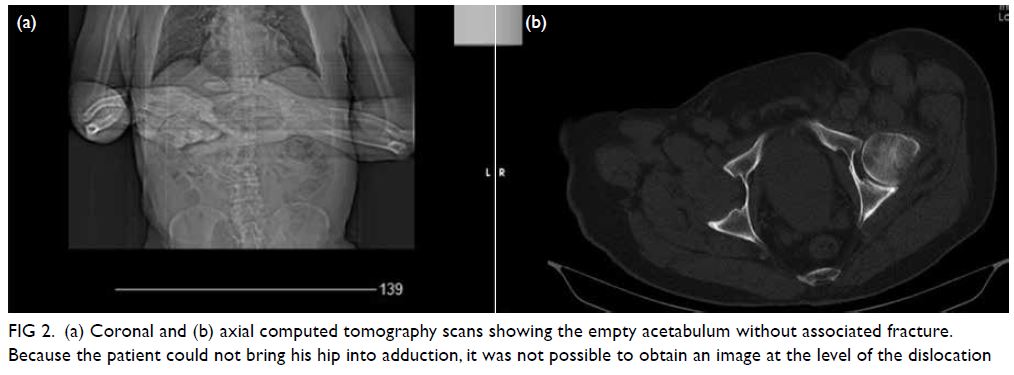

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest

(not shown) revealed an ipsilateral nondisplaced rib

(8-10) and scapular spine fractures. A CT scan of the pelvis (Fig 2) demonstrated an empty acetabulum

with no associated fractures. Later, the patient was

brought to the operating theatre and 0.5 mg/kg

propofol and 0.5 μg/kg remifentanil administered

intravenously for the first 90 s. Thereafter, further

doses of both propofol 0.25 mg/kg and remifentanil

0.25 μg/kg were administered. After 3 to 4 minutes

the patient was adequately sedated and pain-free.

Figure 2. (a) Coronal and (b) axial computed tomography scans showing the empty acetabulum without associated fracture. Because the patient could not bring his hip into adduction, it was not possible to obtain an image at the level of the dislocation

The dislocation was reduced under sedation

and fluoroscopy by manual traction in the line of

deformity, initially followed by adduction of the

femur, resulting in an uneventful reduction (Video 1). Fluoroscopy confirmed that the hip range of

motion was safe after reduction; the hip was safe at

90° of flexion, 20° of adduction, 30° of abduction, and

30° of internal or external rotation.

After clinic follow-up the next day, the patient was discharged home and advised to remain on bed

rest for 3 weeks, and to use a walker (with toe-touch

weight-bearing) solely for going to the toilet.

To prevent heterotopic bone formation and

thromboprophylaxis, 25-mg indomethacin orally

3 times daily and 0.4-mL enoxaparin sodium daily

were prescribed for the first 2 weeks after surgery.

The use of indomethacin for prophylaxis is well

documented in the literature and its use to prevent

heterotopic ossification following treatment for

posterior hip dislocation with acetabular fractures

has been reported by Mitsionis et al.1 Deep venous

thrombosis has rarely been reported after an isolated

hip dislocation.1 Nevertheless, indomethacin for

prophylaxis was prescribed to our patient in view

of the need for prolonged bed rest and his relatively

advanced age.

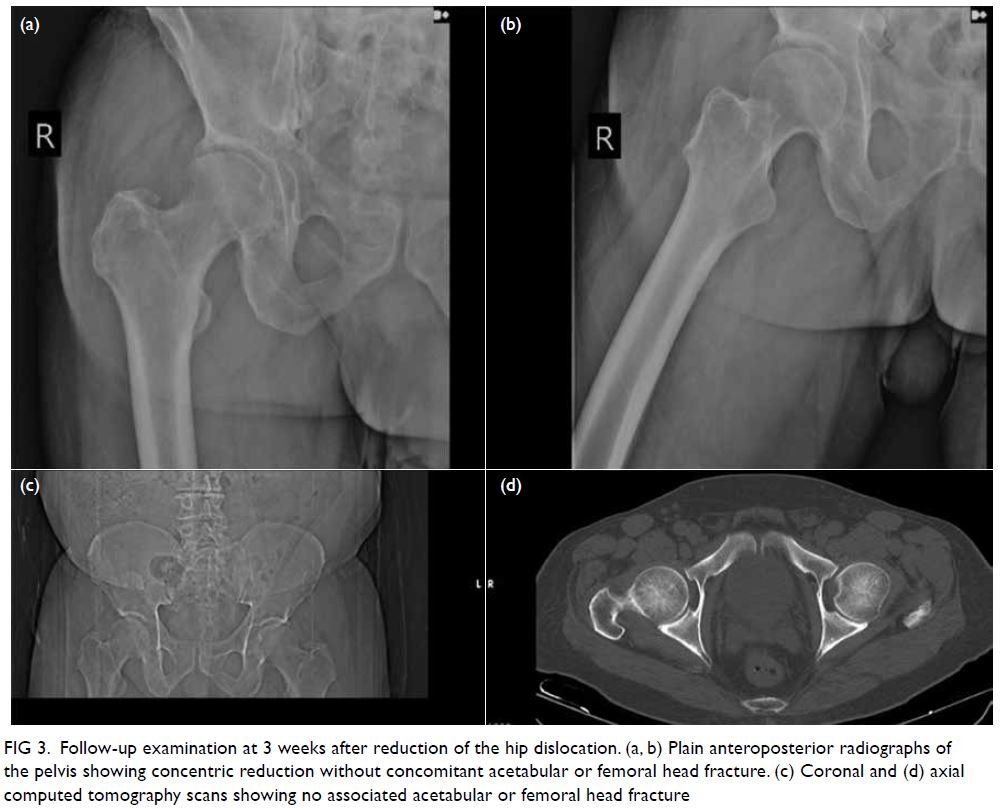

At follow-up examination 3 weeks after

reduction, the patient was able to bear weight with a

mildly antalgic gait (Video 2). The observed antalgic

gait prompted us to be more conservative so the

patient was advised to avoid strenuous activity and

to use crutches with partial weight-bearing. At the

same visit, a post-reduction radiograph and CT scan

was performed to rule out chip or flake fractures of

the femoral head or acetabulum during reduction; if

hip pain persists, a magnetic resonance imaging scan

can be performed to look for evidence of a labral tear.

No associated acetabular or femoral head fracture

was observed (Fig 3). The patient will continue to be monitored for a year for possible aseptic necrosis

and myositis ossificans.

Figure 3. Follow-up examination at 3 weeks after reduction of the hip dislocation. (a, b) Plain anteroposterior radiographs of the pelvis showing concentric reduction without concomitant acetabular or femoral head fracture. (c) Coronal and (d) axial computed tomography scans showing no associated acetabular or femoral head fracture

Discussion

There are two types of inferior hip dislocation: obturator and ischial. Parvaresh et al2 analysed

acetabular development and concluded that between the ages of 12 and 16, the three ossification centres

and triradiate cartilage are ossified in both sexes. It is

realistic then to consider it an adult hip if the patient

is >16 years.2 Few cases of inferior (ischial type) hip

dislocation have been reported. We reviewed the

English-language literature search and found only

five reported cases of inferior hip dislocation in

adult patients (age >16 years).3 4 5 6 7 Among them, our patient is the oldest case reported with uneventful reduction.

Traumatic hip dislocation can cause

complications that include avascular necrosis

(6%-27% for early closed reduction), post-traumatic

osteoarthritis (17%-48%), heterotopic ossification

(up to 32%),1 8 and sciatic nerve injury (approximately 10%).9 To avoid complications, early and uneventful

reduction is critical. In our patient, reduction was

achieved within 2 hours of initial presentation.

Our patient may be the only case documented with

radiographic imaging performed before and after the

reduction (including CT) and video of the reduction

manoeuvre and a clinical video of the patient

(demonstrating the patient walking in the third week

after the reduction).

Brogdon and Woolridge10 described the

mechanism of ischial and obturator injury. In the

ischial type, the person falls on the trunk with the hip

flexed and lands on the flexed knee. The accumulated

force from further flexion of the upper trunk and

body weight may create the momentum to push

the femoral head inferiorly through the shallow and

relatively rimless inferior margin of the acetabulum.

Treatment consists of closed reduction under

sedation or general anaesthesia with axial traction,

together with gradual extension of the femur with

additional internal rotation manoeuvres.9

The common obturator type of dislocation

occurs when the femur is physically abducted and

twisted outwards when the patient slips or when

another force is applied. If the forcible abduction

and external rotation continue with flexion against

the pelvis, the femur is levered anteriorly out

of the acetabulum. Treatment comprises closed

reduction under sedation/general anaesthesia with

longitudinal traction in the direction of the femoral

axis and gentle adduction and flexion of the hip with

additional internal rotation manoeuvres.10

There is a strong consensus in the literature that CT examination be performed prior to reduction to

assess a probable acetabular wall fracture or head

split fracture of the femoral head.8 In the present case,

we could not complete all markings on the CT scan

because the abducted hip automatically blocked the

CT platform. Fortunately, we evaluated the anterior

and posterior acetabular walls and confirmed no

remnants in the acetabular fossa nor any fractures

on the acetabular walls. Based on the reduction and

stability confirmed by physical examination after the

reduction, radiographic examination after reduction

and CT was postponed until 3 weeks after reduction,

when the patient was allowed to fully weight bear for

the first time.

Inferior hip dislocation is rare and can

be successfully treated with closed reduction. Orthopaedic surgeons must be able to diagnose and

optimally treat this type of dislocation. This report

and videos serve as a teaching tool for this reduction

manoeuvre.

Author contributions

Concept or design: Both authors.

Acquisition of data: Both authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Both Gokkus.

Drafting of the manuscript: K Gokkus.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: Both authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Both Gokkus.

Drafting of the manuscript: K Gokkus.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Both authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all treatments, procedures, and consent for

publication.

References

1. Mitsionis GI, Lykissas MG, Motsis E, et al. Surgical management of posterior hip dislocations associated with posterior wall acetabular fracture: a study with a minimum

follow-up of 15 years. J Orthop Trauma 2012;26:460-5. Crossref

2. Parvaresh KC, Pennock AT, Bomar JD, Wenger DR, Upasani VV. Analysis of acetabular ossification from the

triradiate cartilage and secondary centers. J Pediatr Orthop

2018;38:e145-50. Crossref

3. Kolar MK, Joseph S, McLaren A. Luxatio erecta of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:273. Crossref

4. Singh R, Sharma SC, Goel T. Traumatic inferior hip dislocation in an adult with ipsilateral trochanteric fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:220-2. Crossref

5. Walther MM, McCoin NS. Luxatio erecta of the hip. J Emerg Med 2013;44:985-6. Crossref

6. Tekin AÇ, Çabuk H, Büyükkurt CD, Dedeoğlu SS, İmren Y, Gürbüz H. Inferior hip dislocation after falling from height: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;22:62-5. Crossref

7. Zeytin AT, Kaya S, Kaya FB, Ozcelik H. Traumatic inferior hip dislocation. J Med Cases 2015;6:238-9. Crossref

8. Yang RS, Tsuang YH, Hang YS, Liu TK. Traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991;(265):218-27. Crossref

9. Cornwall R, Radomisli TE. Nerve injury in traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;(377):84-91.Crossref

10. Brogdon BG, Woolridge DA. Luxatio erecta of the hip: a critical retrospective. Skeletal Radiol 1997;26:548-52. Crossref