© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Persistent fever in a child with eosinophilia and

systemic symptoms: a case report

CS Wai, MB, ChB, MRCPCH; WF Hui, MB, ChB, MRCPCH; Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD

Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Case

In October 2019, an 8-year-old girl with Diamond–Blackfan anaemia on long-term maintenance steroid

therapy was admitted to a paediatric unit with

meningitis. The meningitis was caused by extended

spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumonia that was sensitive to meropenem but

resistant to cephalosporin and penicillin group

of antibiotics. She was treated with intravenous

meropenem and her fever subsided.

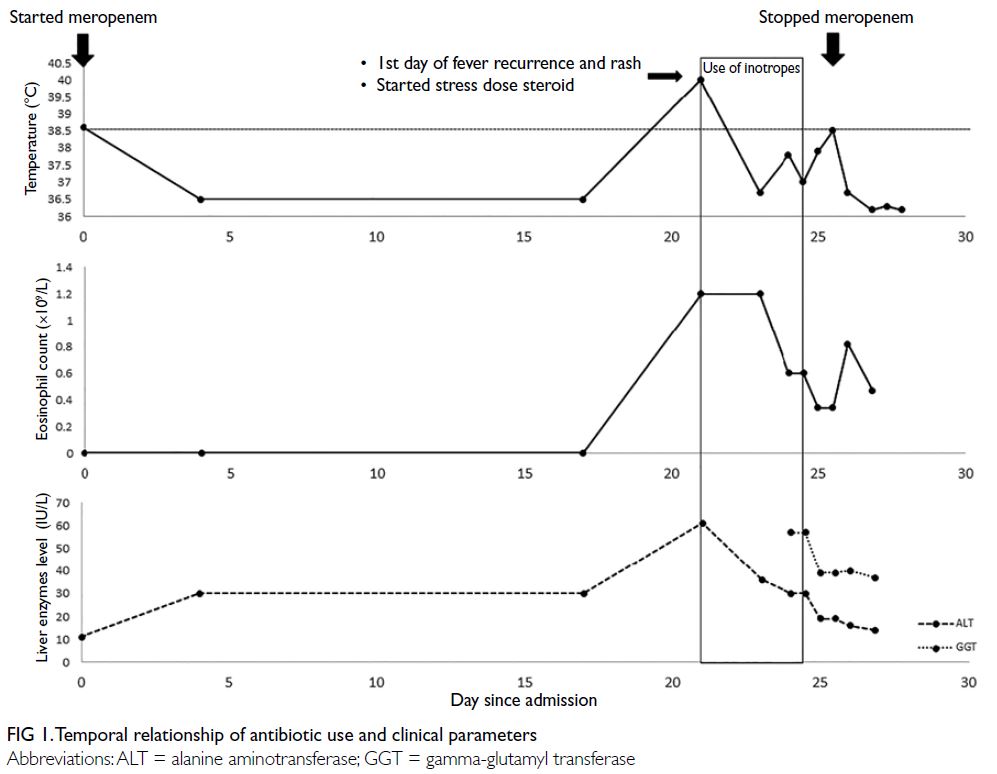

On day 21 of meropenem treatment the

patient’s fever recurred with temperature of 39.7°C

and associated abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and rash

(Fig 1). Physical examination revealed a generalised

blanchable erythematous maculopapular rash over her face, torso, and limbs with no mucosal

involvement or lymphadenopathy (Fig 2). She was

tachycardic at 150 beats per minute but her blood

pressure was normal. She was given fluid boluses

and managed in the paediatric intensive care unit

with a noradrenaline infusion (0.05 μg/kg/min),

prednisolone (increased to 20 mg daily), and the

addition of vancomycin.

Figure 2. An 8-year-old girl with meropenem-associated drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Clinical photographs show rash over (a) torso, (b) face, and (c) limbs

Autoimmune disease and infection workup

including serology for Epstein–Barr virus,

cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus 6 and stool

culture for ova, cysts, and parasites examination

were all negative. The patient’s C-reactive protein

level was 166.43 mg/L (normal range <10 mg/L)

and procalcitonin was 3.63 ng/mL (normal range <0.5 ng/mL). There was evolving eosinophilia since

fever recurrence. The absolute eosinophil count

was elevated to 1.2×109/L (18.9% of total white cell

count) on the first day of fever recurrence with a

peak of 1.4×109/L (35.4% of total white cell count).

Gamma-glutamyl transferase level was elevated

(57 IU/L). Skin biopsy showed non-specific

perivascular lymphocyte infiltration with no

eosinophils. There was no erythema multiforme-like

pattern, spongiosis, interface change or vasculitis

and staining showed no fungus.

Meropenem-associated drug reaction with

eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)

was suspected in view of her fever, rash, persistent

eosinophilia, and deranged liver function alongside prolonged meropenem use and a negative infection

workup. Meropenem was therefore stopped, and her

fever subsided after 6 hours. She was also weaned off

inotrope support. She remained hemodynamically

stable and the rash did not worsen and gradually

subsided in 48 hours. She was discharged from the

paediatric intensive care unit 2 days later. There

was no residual rash and eosinophil count had

normalised 2 weeks after onset of DRESS symptoms.

Discussion

Children with fever and rashes pose challenges in diagnosis and management. Differential diagnoses

must consider “drug versus bug” scenarios.1 Drug

reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

is a rare reaction to certain medications and involves

a widespread skin rash, fever, swollen lymph nodes,

and characteristic blood abnormalities including

eosinophilia, thrombocytopenia and atypical

lymphocytosis.2 Drug reaction with eosinophilia and

systemic symptoms is classified as a form of severe

cutaneous adverse reaction that usually develops

within 6 weeks of initiation of the suspected drug.3 It

may be associated with hepatitis, carditis, interstitial

nephritis or interstitial pneumonitis and is potentially

life-threatening with a reported mortality rate up to

10%.2 The estimated incidence of DRESS is 1 in 1000

to 1 in 10000 drug exposures and is more commonly

observed in adults than children.4

The RegiSCAR (European Registry of Severe

Cutaneous Adverse Reactions) developed a scoring

system in 2007 to classify patients as having no,

possible, probable, or definite DRESS based on

clinical features and laboratory findings.5 Our

patient had a score of 3 and was classified as possible

DRESS, with extreme eosinophilia, rash with

>50% body surface area involvement and negative

microbiological investigations. One point was

deducted from the score for “rash resolution more

than 15 days”. Her aminotransferase and bilirubin

level remained normal throughout although gamma-glutamyl

transferase was elevated. Skin biopsy

revealed perivascular lymphocytosis, a commonly

observed feature among patients with DRESS.5

Skin biopsy is indicated as one of the parameters in

RegiSCAR if facilities are available.

Carbapenems, as members of the beta-lactam

antibiotics, are reported to pose a low risk of allergic

reaction or DRESS. The incidence of rash, pruritis

and urticaria after use of carbapenem has been

reported to be only 0.3 to 3.7%, with rash reported in

only 1.4% of patients treated with meropenem.6 Early

suspicion of DRESS is crucial as discontinuation

of the culprit drug can prevent development of

potentially life-threatening complications. This case

illustrates that all sepsis symptomatology subsided

in a febrile patient with rash and eosinophilia, not by

adding more drugs but by considering the possibility of severe cutaneous adverse reactions and removing

the culprit drug.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have no conflicts of

interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and a parent provided informed consent for all

treatments and procedures. Consent was obtained from the

patient and her parents for publication.

References

1. Hon KL, Choi CL. Steven Johnson syndrome: drug or bug? Indian J Pediatr 2016;83:1508-9. Crossref

2. Walsh SA, Creamer D. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and

systemic symptoms (DRESS): a clinical update and review

of current thinking. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011;36:6-11. Crossref

3. Adler NR, Aung AK, Ergen EN, Trubiano J, Goh MS,

Phillips EJ. Recent advances in the understanding of severe

cutaneous adverse reactions. Br J Dermatol 2017;177:1234-47. Crossref

4. Shiohara T, Kano Y. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and

systemic symptoms (DRESS): incidence, pathogenesis and

management Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017 2020;16:139-47.

5. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug

reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

(DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction.

Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J

Dermatol 2013;169:1071-80. Crossref

6. Linden P. Safety profile of meropenem: an updated review

of over 6,000 patients treated with meropenem. Drug Saf

2007;30:657-68. Crossref