© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Candida glabrata fungal ball cystitis is a rare

complication of conservative treatment of

placenta accreta: a case report

CK Wong, MB, ChB1; LY Cho, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; WL Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; Ingrid YY Cheung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Pathology)2; Chloe HT Yu, MB, BS3; IC Law, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)3; WC Leung, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Pathology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Surgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CK Wong (wongchunkitjack@hotmail.com)

Case report

In October 2019, a 42-year-old pregnant woman was

admitted to hospital at 35+2 weeks of gestation for

an elective caesarean section because of anterior

placenta praevia type I and suspected placenta

accreta. She was gravida 6 and parity 3+2. Her first

pregnancy in 1996 resulted in a normal vaginal

delivery. The second and third pregnancies were

surgically terminated in the first trimester. Fourth

and fifth pregnancies resulted in a lower segment

caesarean section in China due to oligohydramnios

and previous caesarean section.

The patient had an uneventful antenatal course

in the current pregnancy. Nonetheless ultrasound

examination at 35+2 weeks of gestation revealed an

anterior placenta praevia type I with the placenta’s

leading-edge 2.7 cm from the os. A diagnosis of

placenta accreta was made due to vascularities over

the subserosal surface of the lower segment.

A classical caesarean section was performed

after completing a course of antenatal corticosteroid

at 36+4 weeks of gestation. Around four-fifths of the

placenta separated spontaneously after 30 minutes.

The placenta was trimmed away and 3 × 3 cm of

anterior adherent placenta around the internal os

was left in place. Active bleeding from the lower

segment of the uterus and anterior placental bed

was controlled with Sengstaken–Blakemore balloon

tamponade (Rüsch Teleflex, Germany). Uterine

artery embolisation was performed at the same

operation by interventional radiologists. Total blood

loss for the operation was 500 mL.

After surgery, the patient was transferred

to the intensive care unit. Balloon tamponade was

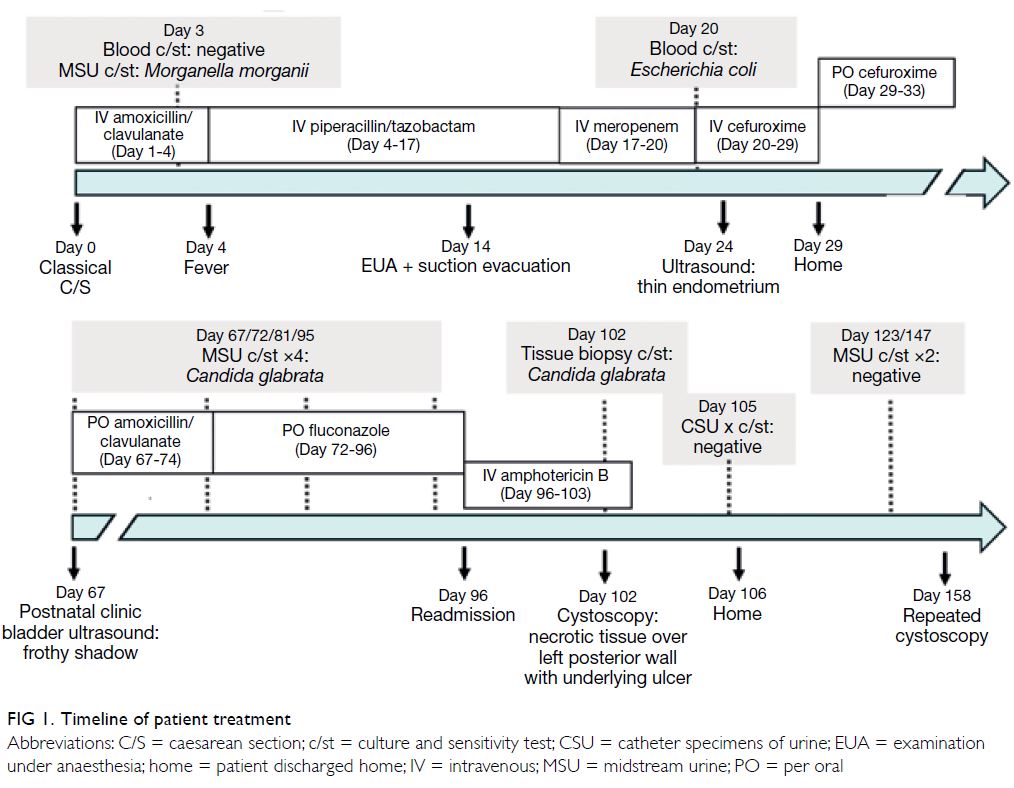

removed on day 1 (Fig 1). Prophylactic amoxicillin

and clavulanate was administered intravenously

after the operation. She complained of dysuria

and developed a persistent swinging fever from

day 2. Amoxicillin and clavulanate was switched

to piperacillin/tazobactam on day 4 after blood and urine tests for sepsis. Culture of midstream

urine showed Morganella morganii sensitive to

piperacillin/tazobactam and a gram-negative

bacillus. Microbiologists advised continuation of

piperacillin/tazobactam for 7 to 10 days.

Examination under anaesthesia and

ultrasound-guided suction evacuation were

performed on day 14 due to increased per-vaginal

bleeding. Intra-operatively, yellowish pus was seen

leaking from the cervical os and retained product of

gestation weighing 48 g was retrieved. Culture of the

pus grew Escherichia coli sensitive to piperacillin/tazobactam. The patient again presented with fever

postoperatively and blood culture revealed E coli

septicaemia. Piperacillin/tazobactam was switched

to meropenem on day 17. Blood culture sensitivity

testing revealed E coli sensitive to meropenem

and cefuroxime. Hence, meropenem was switched

to cefuroxime. Ultrasound examination on day

24 revealed no evidence of retained product of

gestation. Cefuroxime was continued for 14 days.

At 5-week follow-up examination, the

patient reported a 1-week history of whitish debris

in her urine, dysuria, and urinary frequency.

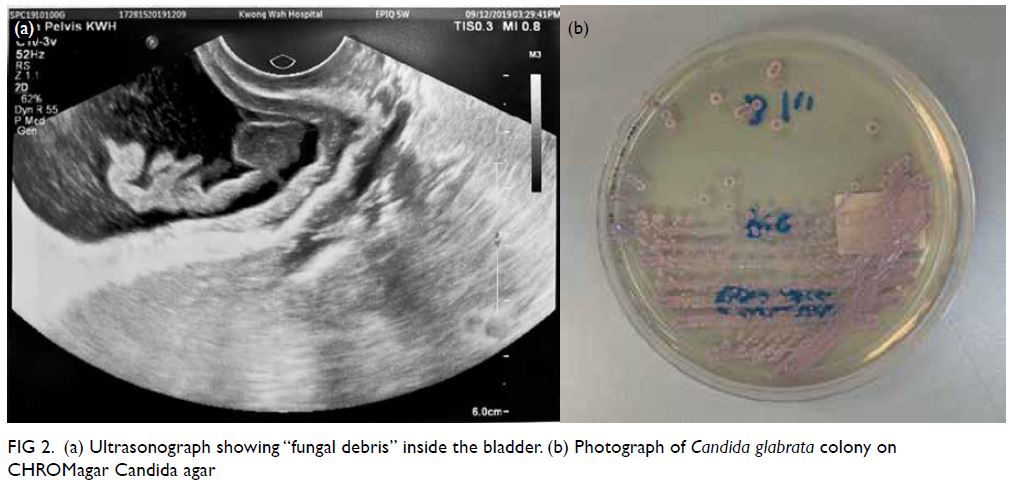

Ultrasonography revealed incomplete emptying of

the bladder with a lot of frothy shadows (Fig 2a).

Urinary tract infection was suspected so amoxicillin

and clavulanate and phenazopyridine were prescribed

for 1 week. Culture of the midstream urine showed

Candida glabrata (Fig 2b). A microbiologist was

consulted and fluconazole 400 mg prescribed for 10

days.

Figure 2. (a) Ultrasonograph showing “fungal debris” inside the bladder. (b) Photograph of Candida glabrata colony on CHROMagar Candida agar

Susceptibility testing of the C glabrata isolated from urine collected after admission was performed by using Sensititre YeastOne (TREK Diagnostic

Systems, United Kingdom) and revealed a required

fluconazole minimal inhibitory concentration of

16 μg/mL, confirming that it was in the susceptible-dose

dependent category. However, the patient’s

symptoms persisted after completing 24 days of fluconazole and ultrasound showed persistent

“fungal debris” inside the bladder. She was

readmitted 13 weeks after the operation for further

management. Amphotericin B deoxycholate was administered intravenously for 7 days. A drug-related

fever developed during the first dose but resolved

after premedication with oral acetaminophen and

intravenous diphenhydramine.

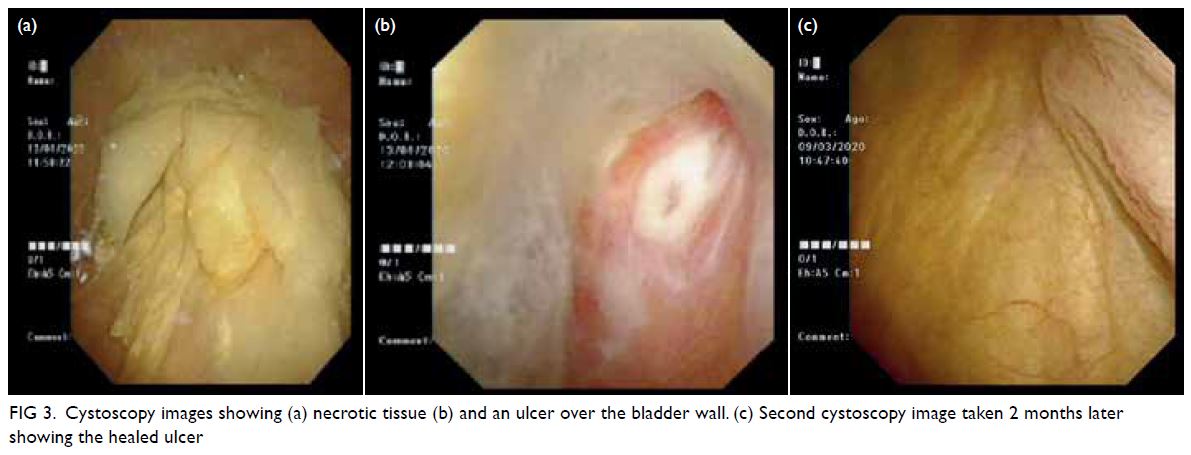

Flexible cystoscopy revealed necrotic tissue

approximately 3 × 4 cm over the left posterior

bladder wall, away from the left ureteric orifice, with

an underlying ulcer (Fig 3a and b). It was removed

with forceps and a basket. A fistula was suspected,

and second flexible cystoscopy scheduled 2 months

later. A computed tomography urogram with

contrast was arranged to exclude fistula.

Figure 3. Cystoscopy images showing (a) necrotic tissue (b) and an ulcer over the bladder wall. (c) Second cystoscopy image taken 2 months later showing the healed ulcer

The second flexible cystoscopy revealed a

normal bladder and a healed ulcer over the left

posterior wall (Fig 3c). Computed tomography

urogram showed no evidence of fistula. During

postnatal follow-up, there were no urinary

symptoms.

Discussion

This is the first case of C glabrata cystitis as a complication in our case series of planned

conservative management of placenta accreta.1

Candida species are a part of the normal flora of the

gastrointestinal and vaginal tracts. The incidence of

candiduria has been increasing in recent decades

and the presence of C glabrata has become clinically

significant due to its high resistance to routine

antifungal agents. Risk factors for candiduria in our

case included urinary catheterisation, intensive care

unit stay, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, female

sex, and prior surgery.2

The placental remnants in our case induced

infection and septicaemia. Subsequent prolonged

use of broad-spectrum antibiotics predisposed

our patient to fungal cystitis. There was no clinical

or pathological evidence of placenta percreta.

Chandraharan et al3 introduced the use of the

Triple-P procedure to manage patients with morbidly

adherent placenta. As the Triple-P procedure removes all intrauterine placental remnants, it may

reduce the risk of intrauterine infection and sepsis.

Nevertheless, there is limited surgical expertise in

this procedure in our unit.

Compared with other Candida species, many

C glabrata isolates are resistant to azoles due to

efflux pump–mediated resistance, genetic alterations

under stress and biofilm protection.4 A study in the

United States revealed that 14% of C glabrata isolates

were resistant to fluconazole.5

The presence of fungus ball/fungal bezoars in

urinary tract infection is extremely rare in adults.

According to treatment guidelines of the Infectious

Diseases Society of America, removal of the

obstructing mycelial mass by surgical or endoscopic

means is strongly recommended.6 Although culture

results revealed that the C glabrata was susceptible-dose-dependent to fluconazole, use of fluconazole

alone was likely to be insufficient due to the fungal

ball in the bladder. A multidisciplinary approach

including microbiologists and urologists is essential.

In symptomatic Candida cystitis, first-line

treatment is oral fluconazole 200 mg daily for 2 weeks.

For fluconazole-resistant C glabrata, amphotericin

B deoxycholate or oral flucytosine are the drugs

of choice. Around 50% of patients prescribed an

amphotericin B infusion experience infusion-related

adverse events, such as fever, chills, rigors,

hypotension, and rarely, hypokalaemia resulting in

ventricular fibrillation. In addition, renal toxicity is

a well-known adverse effect.5 Close monitoring of

renal function and electrolytes is essential.

Placenta accreta spectrum treated

conservatively by leaving the placenta in situ

is a recognised and successful management

option, but is associated with risks of infection or

postpartum haemorrhage. Our case demonstrates that fungal infection can develop during the period of conservative management and requires

multidisciplinary consultation.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CK Wong, WC Leung.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: CK Wong, WC Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: CK Wong, WC Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank interventional radiologists Dr KH Lee and Dr CW Tang for their contributions to this report.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, provided informed consent for all treatments and procedures, and provided consent for publication.

References

1. Lo TK, Yung WK, Lau WL, Law B, Lau S, Leung WC. Planned conservative management of placenta accreta—experience of a regional general hospital. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;27:291-6. Crossref

2. Gajdács M, Dóczi I, Ábrók M, Lázár A, Burián K. Epidemiology of candiduria and Candida urinary tract

infections in inpatients and outpatients: results from

a 10-year retrospective survey. Cent European J Urol

2019;72:209-14.

3. Chandraharan E, Rao S, Belli A, Arulkumaran S. The

Triple-P procedure as a conservative surgical alternative

to peripartum hysterectomy for placenta percreta. Int J

Gynecol Obstet 2012;117:191-4. Crossref

4. Rodrigues CF, Silva S, Henriques M. Candida glabrata: a

review of its features and resistance. Eur J Clin Microbiol

Infect Dis 2013;33:673-88. Crossref

5. Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Hollis RJ, et al. Variation in

susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida glabrata

to fluconazole according to patient age and geographic

location in the United States in 2001 to 2007. J Clin

Microbiol 2009;47:3185-90. Crossref

6. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive

Summary: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management

of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases

Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:409-17. Crossref