Hong Kong Med J 2023 Oct;29(5):453–5 | Epub 27 Sep 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Calcific myonecrosis misdiagnosed as right leg abscess: a case report

CY Lee, MB, BS1; CH Lin, MB, BS2

1 Department of Medical Imaging, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

2 Department of Medical Imaging, Chi Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan

Corresponding author: Mr CH Lin (chienhung0822@gmail.com)

Case presentation

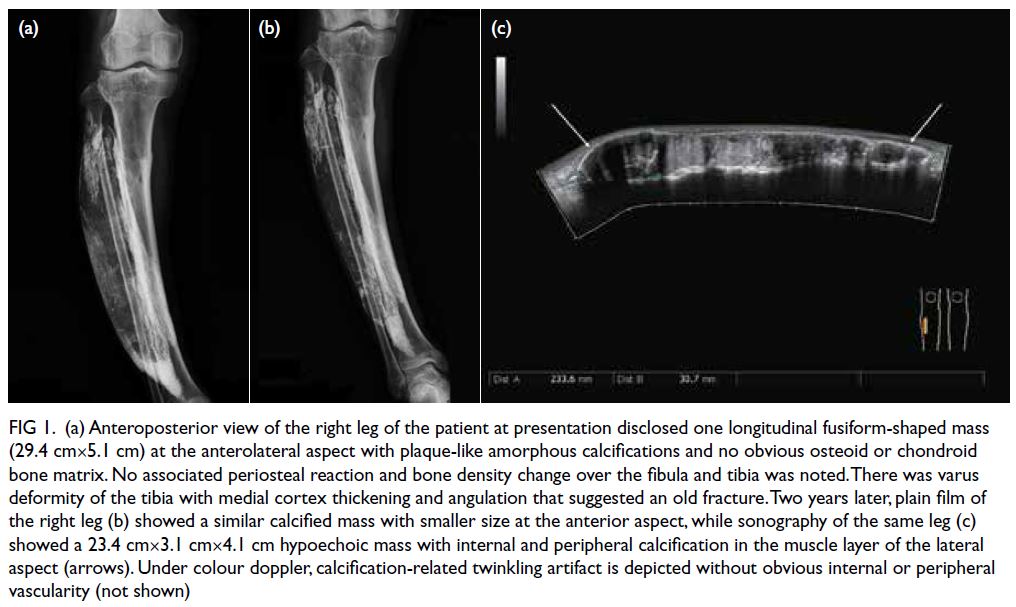

A 63-year-old man attended hospital with a 2-year

history of a slow-growing painful mass in his right

leg. He had undergone successful surgical drainage

of an abscess. Plain X-ray of the right leg at that time

(Fig 1a) revealed a longitudinally distributed fusiform

mass (29.4 cm×5.1 cm) with plaque-like amorphous

calcifications at the right anterolateral aspect. No

obvious periosteal reaction or cortical destruction

of the tibia or fibula was noted. There was varus

deformity of the tibia with medial cortex thickening

and angulation that suggested old fracture. He had

sustained a crush injury to the right leg 10 years

previously and developed peroneal nerve injury with

foot drop.

Figure 1. (a) Anteroposterior view of the right leg of the patient at presentation disclosed one longitudinal fusiform-shaped mass (29.4 cm×5.1 cm) at the anterolateral aspect with plaque-like amorphous calcifications and no obvious osteoid or chondroid bone matrix. No associated periosteal reaction and bone density change over the fibula and tibia was noted. There was varus deformity of the tibia with medial cortex thickening and angulation that suggested an old fracture. Two years later, plain film of the right leg (b) showed a similar calcified mass with smaller size at the anterior aspect, while sonography of the same leg (c) showed a 23.4 cm×3.1 cm×4.1 cm hypoechoic mass with internal and peripheral calcification in the muscle layer of the lateral aspect (arrows). Under colour doppler, calcification-related twinkling artifact is depicted without obvious internal or peripheral vascularity (not shown)

Physical examination of the patient revealed a

mass at the anterolateral aspect of the right leg. There

were no skin changes, redness or tenderness. The

patient was afebrile. Biochemical and haematological investigations were normal. The range of motion of

the right lower limb was not impaired but obvious

muscle atrophy at the posterolateral compartment

of the right leg was noted. Further imaging was

requested due to concerns about malignancy.

The plain film of the right leg 2 years later

(Fig 1b) showed a similar but smaller calcified mass

at the anterior aspect. A 23.4 cm×3.1 cm×4.1 cm

corresponding hypoechoic mass with internal and

peripheral calcification foci in the muscle layer

of the lateral aspect of the same leg and paucity of

vascularity was observed under lower extremity

sonography examination using Toshiba Aplio 500

(Canon Medical Systems, Tustin [CA], US) [Fig 1c].

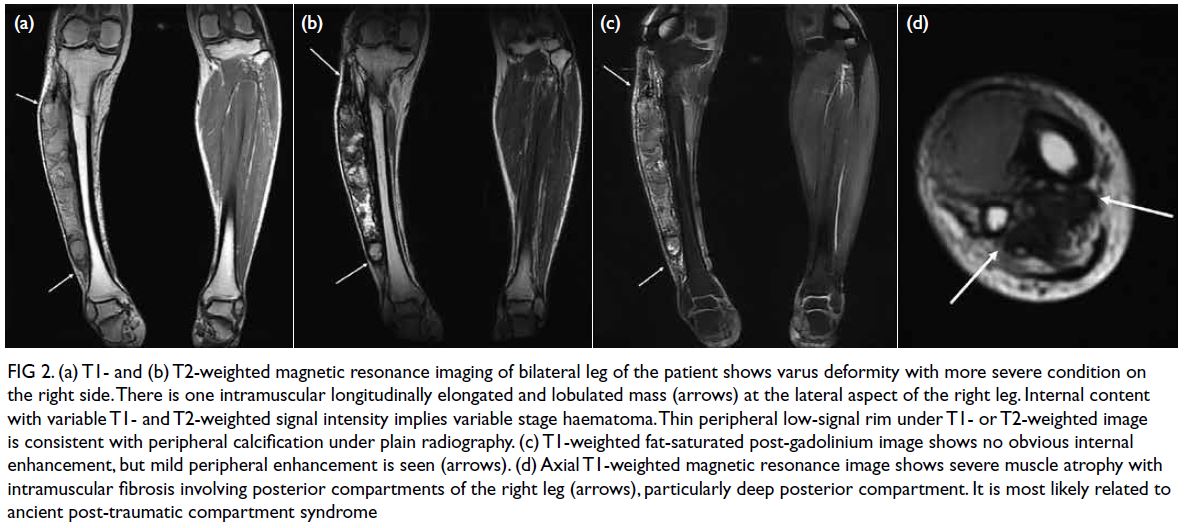

Further magnetic resonance imaging study using

Discovery MR750 (GE Healthcare, Chicago [IL], US)

revealed an elongated and lobulated intramuscular

cystic mass with variable internal T1- or T2-weighted signal intensity and low-signal peripheral rim (Fig 2a and 2b). Mild peripheral enhancement

after intravenous gadolinium administration was

noted (Fig 2c). Additional findings included varus

deformity of the right tibia and severe muscle

atrophy with muscle fibrosis involving the deep

posterior and lateral compartments of the right leg.

Figure 2. (a) T1- and (b) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of bilateral leg of the patient shows varus deformity with more severe condition on the right side. There is one intramuscular longitudinally elongated and lobulated mass (arrows) at the lateral aspect of the right leg. Internal content with variable T1- and T2-weighted signal intensity implies variable stage haematoma. Thin peripheral low-signal rim under T1- or T2-weighted image is consistent with peripheral calcification under plain radiography. (c) T1-weighted fat-saturated post-gadolinium image shows no obvious internal enhancement, but mild peripheral enhancement is seen (arrows). (d) Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows severe muscle atrophy with intramuscular fibrosis involving posterior compartments of the right leg (arrows), particularly deep posterior compartment. It is most likely related to ancient post-traumatic compartment syndrome

The tibial and fibular bones were intact and

without involvement. No regional inflammatory

change around the calcified cystic mass, prominent

vascularity and significant peripheral enhancement

was observed. The findings were consistent with

calcific myonecrosis and muscle fibrosis, which

is most likely related to a remote post-traumatic

compartment syndrome (Fig 2d). In the absence of

any symptoms that impacted daily living, the patient

declined invasive treatment and opted for regular

follow-up.

Discussion

Calcific myonecrosis is a rare, delayed manifestation of post-traumatic muscle injury or sequelae of

neurovascular injury that occurs almost exclusively

in the lower limbs.1 It is likely due to previous muscle

injury complicated by compartment syndrome.1

Muscle injury may be a result of trauma, nerve

injury with denervation, snake bite complicated by

compartment syndrome,2 chronic inflammation (eg,

dermatomyositis),3 or repeated contraction due to

static epilepsy.4

The most common site of compartment

syndrome in the leg is the anterior compartment

followed by the lateral and deep posterior compartment. Compartment syndrome results

in chronic vascular insufficiency and ischaemic

change to muscular tissue. Following long-term

hypoperfusion, muscles become necrotic and

fibrosed with a consequent reduction in mass and

development of contracture. If extensive necrosis

with cystic change, haematoma formation, and

calcification are present, calcific myonecrosis may

develop, evident as a slow-growing mass.

In most cases, calcific myonecrosis presents as a

painful or painless mass. Pain is likely due to pressure

on surrounding tissue. Signs of inflammation (skin

erythema, tenderness, and warmth) are often absent.

Cosmetic problems and concerns of malignancy (eg,

soft tissue sarcoma) are common reasons for seeking

medical advice after decades of the disease course.

Plain radiography and computed tomography

usually reveal lesions confined to muscle

compartments in a longitudinally oriented

pattern with peripheral fusiform and amorphous

calcifications parallel to muscle orientation. Magnetic

resonance imaging usually shows a circumscribed

fusiform intramuscular cystic mass with the

peripheral calcification rim in the longitudinally

oriented pattern as muscle bulk. The internal content

usually shows variable signal intensities in T1- and

T2-weighted images that depend on the internal

content (proteinaceous necrotic fluid, serous fluid,

and different blood stages). Mild peripheral rim

enhancement may be observed following intravenous

gadolinium administration. The central cystic part

lacks enhancement secondary to extensive necrosis.

Post-compartment syndrome–related muscle atrophy, fibrosis, and contracture usually coexist in

these disease entities.1 Other common differential

diagnoses should be excluded including myositis

ossificans, soft tissue sarcoma, and musculoskeletal

tuberculosis.5 6

Calcific myonecrosis is essentially benign

although previous reports have revealed

postoperative complications such as sinus tract

formation,7 poor wound healing, and secondary

infection. This implies that wound healing is difficult,

probably due to previous compartment syndrome

and chronic microvascular insufficiency. In cases

of uninfected calcific myonecrosis, observation

is the recommended management given the high

risk of postoperative complications. Nonetheless

cosmetic problems and symptoms may persist.1 For

calcific myonecrosis with infection, conservative

management with wound dressing and antibiotics

is usually not sufficient. Extensive debridement,

removal of diseased tissue, and flap coverage are

recommended.8 Secondary surgery may be needed

if postoperative complications (poor wound healing,

secondary infection, and sinus tract formation)

are observed. Advanced wound management (eg,

negative pressure wound therapy) facilitates healing

with a moist environment and topical negative

pressure.8 9

In our patient, the calcified mass in his right

leg 2 years previously had been drained since

abscess was suspected. Plain X-ray at that time

suggested calcific myonecrosis or other differential

diagnoses (myositis ossificans, soft tissue sarcoma,

etc.). Thus, further magnetic resonance imaging

surveys and more details about a previous crush

injury would have been helpful to reach a diagnosis

and avoid unnecessary surgery. Knowledge of

calcific myonecrosis is important for clinicians and

radiologists to optimise patient care.

Conclusion

Calcific myonecrosis is a benign disease process.

Generally, ‘do not touch’ is a treatment strategy.

Prompt recognition, proper diagnosis based on

imaging, and detailed history taking are important.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CH Lin.

Acquisition of data: CY Lee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CY Lee.

Drafting of the manuscript: CY Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Acquisition of data: CY Lee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CY Lee.

Drafting of the manuscript: CY Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Both authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has provided informed consent for the

treatment/procedures, and consent for publication.

References

1. O’Dwyer HM, Al-Nakshabandi NA, Al-Muzahmi K, Ryan A,

O’Connell JX, Munk PL. Calcific myonecrosis: keys to

recognition and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol

2006;187:W67-76. Crossref

2. Yuenyongviwat V, Laohawiriyakamo T, Suwanno P,

Kanjanapradit K, Tanutit P. Calcific myonecrosis following

snake bite: a case report and review of the literature. J Med

Case Rep 2014;8:193. Crossref

3. Batz R, Sofka CM, Adler RS, Mintz DN, DiCarlo E.

Dermatomyositis and calcific myonecrosis in the leg:

ultrasound as an aid in management. Skeletal Radiol

2006;35:113-6. Crossref

4. Karkhanis S, Botchu R, James S, Evans N. Bilateral

calcific myonecrosis associated with epilepsy. Clin Radiol

2013;68:e349-52. Crossref

5. De Vuyst D, Vanhoenacker F, Gielen J, Bernaerts A,

De Schepper AM. Imaging features of musculoskeletal

tuberculosis. Eur Radiol 2003;13:1809-19. Crossref

6. Burrill J, Williams CJ, Bain G, Conder G, Hine AL,

Misra RR. Tuberculosis: a radiologic review. Radiographics

2007;27:1255-73. Crossref

7. Jeong BO, Chung DW, Baek JH. Management of calcific

myonecrosis with a sinus tract: a case report. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2018;97:e12517. Crossref

8. Sreenivas T, Nandish Kumar KC, Menon J, Nataraj AR.

Calcific myonecrosis of the leg treated by debridement

and limited access dressing. Int J Low Extrem Wounds

2013;12:44-9. Crossref

9. Tan AM, Loh CY, Nizamoglu M, Tare M. A challenging

case of calcific myonecrosis of tibialis anterior and hallucis

longus muscles with a chronic discharging wound. Int

Wound J 2018;15:170-3. Crossref