Posaconazole-induced gynaecomastia in a patient with COVID-19–associated mucormycosis: a case report

Hong Kong Med J 2025 Aug;31(4):316–8 | Epub 6 Aug 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Posaconazole-induced gynaecomastia in a patient with COVID-19–associated mucormycosis: a case report

Mohammadreza Salehi, MD1; Hossein Khalili, PharmDM2; Amirmasoud Kazemzadeh, MD3; Maryam Alaei, PharmD2; Azin Tabari, MD4

1 Research Centre for Antibiotic Stewardship and Antimicrobial Resistance, Department of Infectious Diseases, Imam Khomeini Hospital

Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2 Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3 Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4 Department of Ear, Nose, and Throat Diseases, School of Medicine, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Corresponding author: Dr Amirmasoud Kazemzadeh (amirm.kazemzadeh@gmail.com)

Case presentation

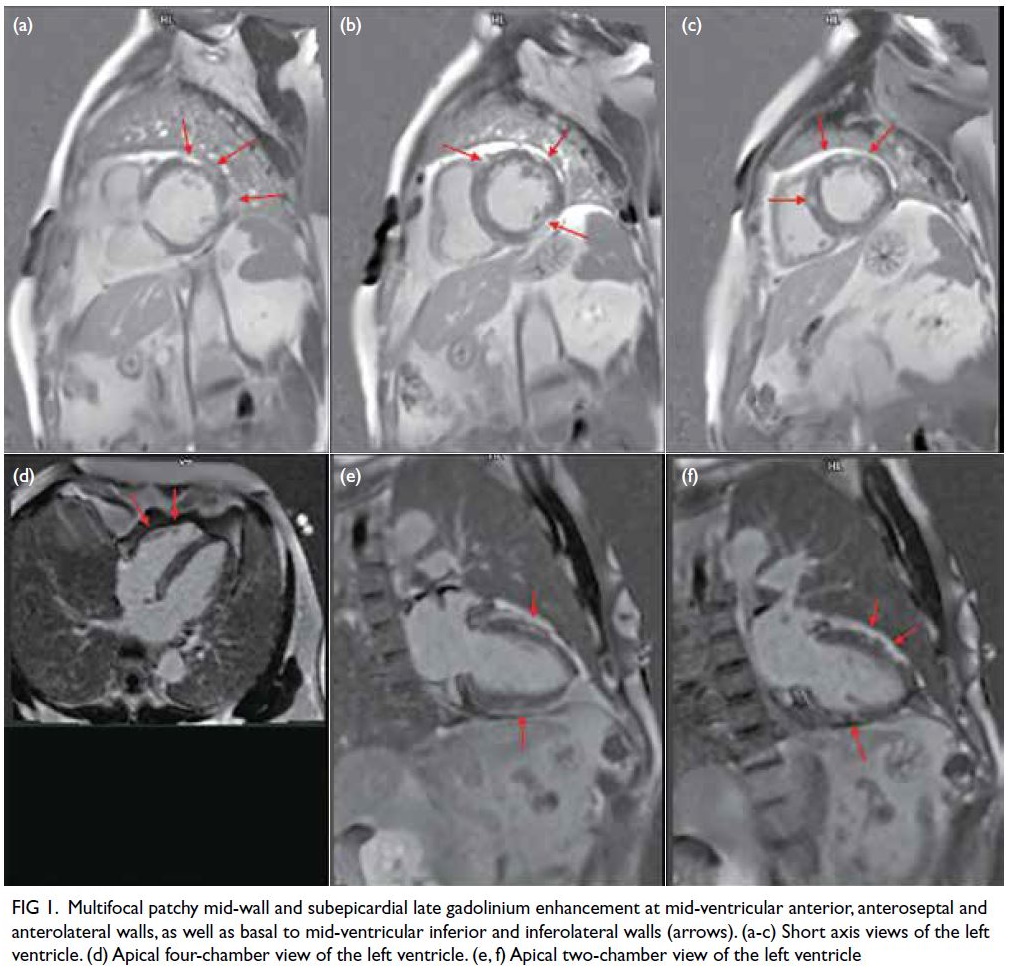

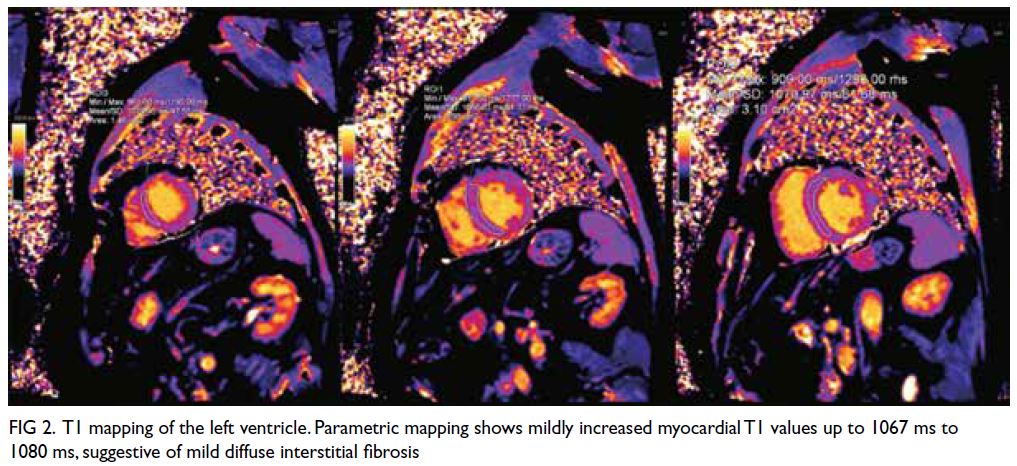

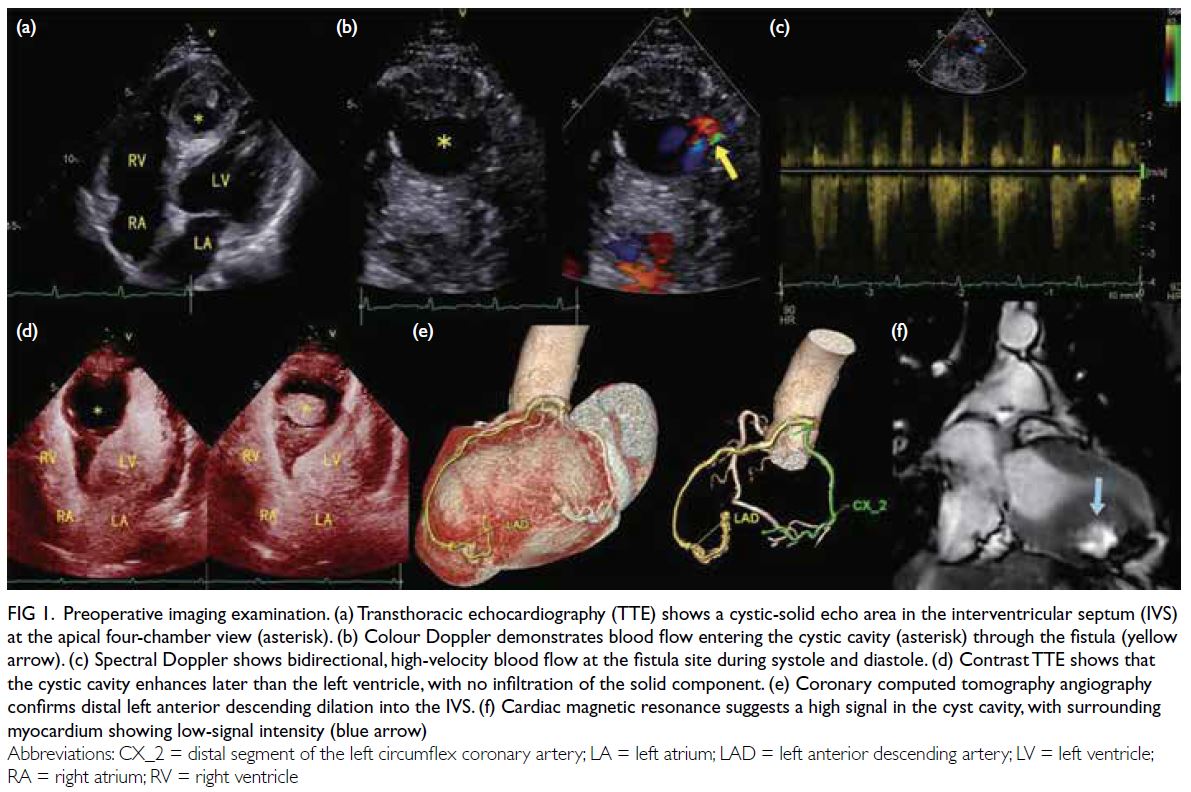

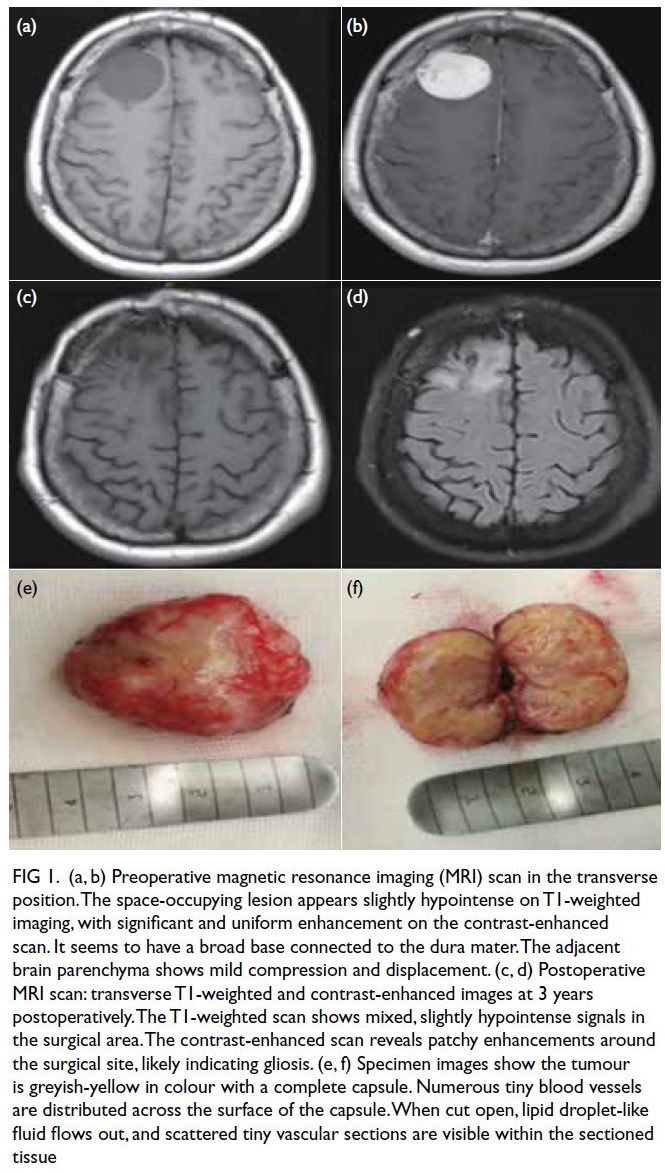

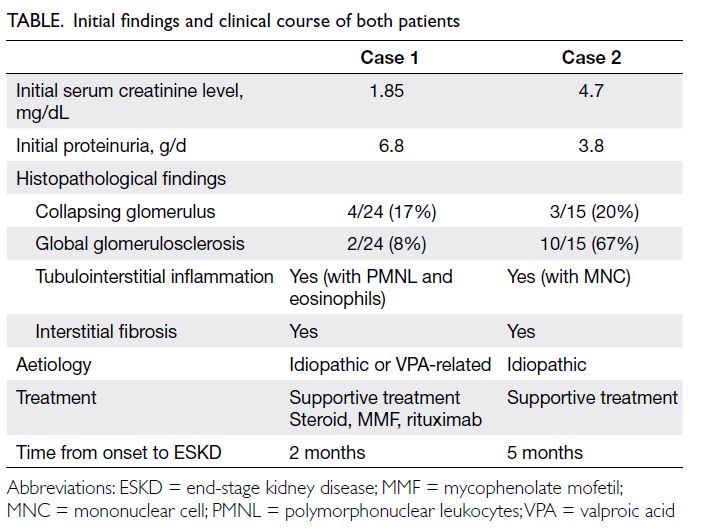

A 49-year-old man with a history of poorly controlled

diabetes for over 10 years was hospitalised 6 months

earlier, on 2 April 2023, for severe COVID-19

infection. He was discharged after 3 weeks but later

developed right-sided facial pain and diplopia. He

was diagnosed with sino-orbital mucormycosis

based on the clinical symptoms and imaging

features (Fig a). Histopathological examination of a sinus biopsy revealed invasive ribbon-like hyphae,

confirming the diagnosis. The patient underwent

sinus and surgical debridement of the orbit and was

prescribed antifungal treatment. After two surgical

debridements of necrotic tissue and 6 weeks of

combination antifungal treatment with liposomal

amphotericin B (400 mg daily via infusion) plus

posaconazole (300 mg twice daily on the first day

and 300 mg daily intravenously thereafter), the

patient was discharged in good general health but

with right eye blindness. He was advised to continue

treatment with oral posaconazole (300 mg twice

daily on the first day, then 300 mg daily thereafter)

for a duration of 12 weeks and to control his blood

sugar with insulin.

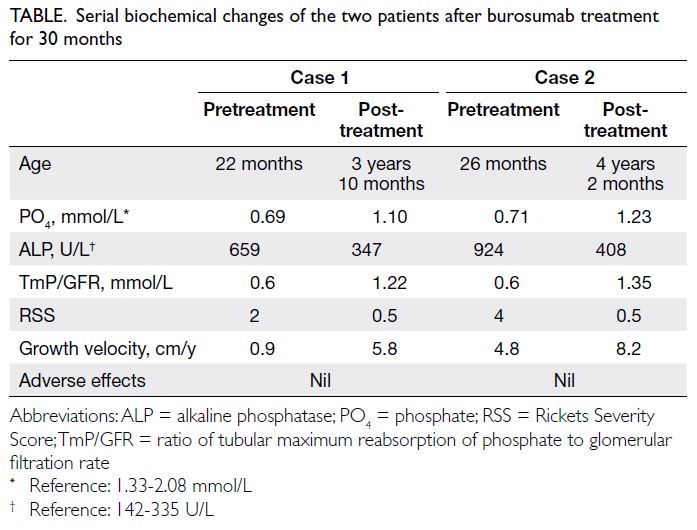

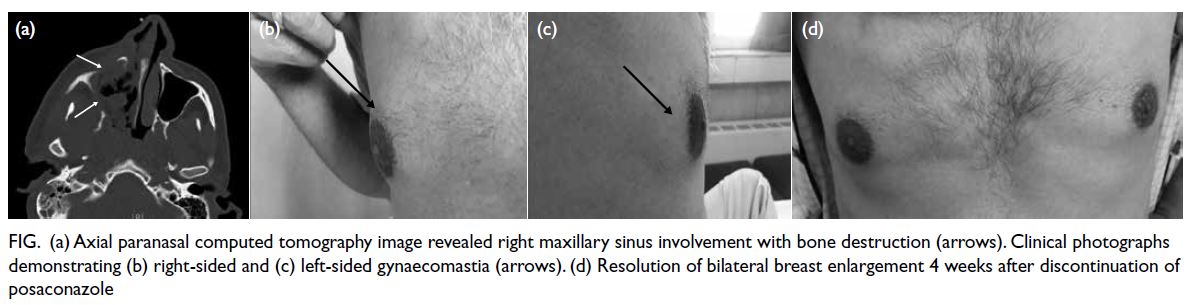

Figure. (a) Axial paranasal computed tomography image revealed right maxillary sinus involvement with bone destruction (arrows). Clinical photographs demonstrating (b) right-sided and (c) left-sided gynaecomastia (arrows). (d) Resolution of bilateral breast enlargement 4 weeks after discontinuation of posaconazole

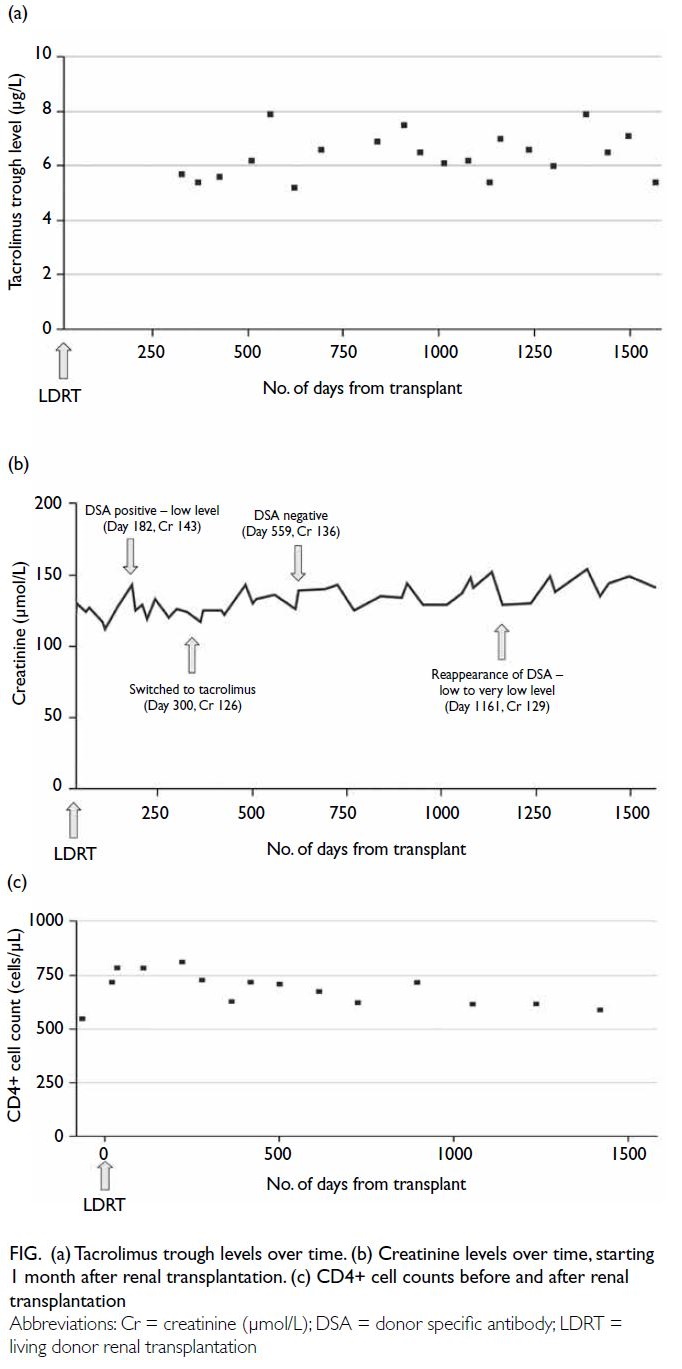

In September 2023, 2 months after discharge,

the patient presented to the hospital for follow-up,

complaining of increased bilateral breast volume,

particularly in the right breast (Fig b and c). He had

first noticed this increase in volume approximately

1 month after hospitalisation, and it had gradually

intensified.

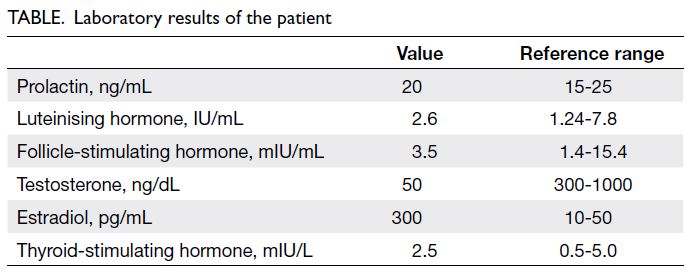

Clinical examination revealed bilateral breast

swelling with increased breast adipose tissue volume,

more pronounced on the right side. No tenderness

or palpable mass was detected. Ultrasound findings

were consistent with gynaecomastia. Hormone

testing showed a normal prolactin level and pituitary

axes but markedly decreased testosterone and

elevated oestrogen levels (Table).

In view of these results and the possible

association of gynaecomastia with azole use,

posaconazole was discontinued. The patient was

prescribed liposomal amphotericin B 400 mg

daily and monitored daily to ensure compliance

with medication and to evaluate any possible side-effects.

He exhibited minor hypokalaemia while

receiving amphotericin B, which resolved with the

administration of potassium supplements. There was no evidence of hyperaldosteronism during treatment

with posaconazole. Following the discontinuation of

posaconazole, the patient’s gynaecomastia improved

significantly over 4 weeks (Fig d).

Discussion

At the time of writing, this report represents the

second documented case of posaconazole-induced

gynaecomastia. Information on this adverse effect is

limited, despite its recognised association with azole

use. Given the common use of posaconazole for the

prevention and treatment of mucormycosis, other

patients may be at risk of similar complications.

Disseminating this information is essential for

clinical pharmacists to manage such cases effectively

Our case was a middle-aged man with a

history of diabetes and COVID-19, who developed

gynaecomastia following the prescription of

posaconazole for mucormycosis. Gynaecomastia

is a benign enlargement of the breast tissue that

may occur in many adult men.1 Physiological

gynaecomastia in infants, adolescents, and older

adult men is usually unilateral. Non-physiological

gynaecomastia may arise in patients with chronic

diseases such as hypogonadism, cirrhosis,

neoplasms or uraemia, or as a consequence of drug

use. Additionally, non-physiological gynaecomastia

may cause localised pain.2 In our patient, bilateral

and painless non-physiological gynaecomastia

developed as a consequence of azole use.

Azole antifungals are the mainstay of

prevention and treatment for invasive fungal

infections such as mucormycosis.3 Most reported

cases of azole-induced gynaecomastia have involved

patients taking ketoconazole and, to a lesser

extent, itraconazole. Both inhibit cytochrome P450

enzymes involved in steroidogenesis.4 In-vitro

evidence suggests that posaconazole can inhibit

cytochrome P450 17A1, an enzyme involved in the

lyase reaction required for androgen production. In

addition, posaconazole, similar to ketoconazole, may

inhibit hepatic oestrogen metabolism.5 Accordingly,

our patient’s serum testosterone level was lower than normal, while the oestradiol level was significantly

elevated. This is comparable to the first reported

case of posaconazole-induced gynaecomastia by

Thompson et al.6 In that patient, who was prescribed

long-term posaconazole for coccidioidomycosis

(300 mg/day slow-release formulation), the oestradiol

level was raised despite a normal testosterone level.

Notably, gynaecomastia did not improve following

a switch from posaconazole to voriconazole. In

contrast, our patient showed improvement after the

complete discontinuation of azole agents.

The main limitation of this report is the

absence of a serum posaconazole level, as testing

was unavailable due to economic constraints

affecting resource availability. This limits the ability

to draw a definitive conclusion regarding the

association of posaconazole with the development

of gynaecomastia, or the observed improvement

following its discontinuation.

Author contributions

Concept or design: M Salehi, H Khalili.

Acquisition of data: A Kazemzadeh, M Alaei.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M Salehi, A Tabari.

Acquisition of data: A Kazemzadeh, M Alaei.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M Salehi, A Tabari.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Mrs Fariba Zamani for language editing of the manuscript.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency

in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved of by the institutional review

board of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Ref

No.: IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1403.165). Written consent was

obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

References

1. Fagerlund A, Lewin R, Rufolo G, Elander A, Santanelli di

Pompeo F, Selvaggi G. Gynecomastia: a systematic review.

J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2015;49:311-8. Crossref

2. Jin Y, Fan M. Treatment of gynecomastia with prednisone:

case report and literature review. J Int Med Res

2019;47:2288-95. Crossref

3. Benitez LL, Carver PL. Adverse effects associated with

long-term administration of azole antifungal agents. Drugs

2019;79:833-53. Crossref

4. Satoh T, Fujita KI, Munakata H, et al. Studies on the

interactions between drugs and estrogen: analytical method for prediction system of gynecomastia induced

by drugs on the inhibitory metabolism of estradiol using

Escherichia coli coexpressing human CYP3A4 with human

NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Anal Biochem

2000;286:179-86. Crossref

5. Yates CM, Garvey EP, Shaver SR, Schotzinger RJ, Hoekstra WJ. Design and optimization of highly-selective, broad

spectrum fungal CYP51 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett

2017;27:3243-8. Crossref

6. Thompson GR 3rd, Surampudi PN, Odermatt A.

Gynecomastia and hypertension in a patient treated with

posaconazole. Clin Case Rep 2020;8:3158-61. Crossref