Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided pulmonary wedge resection in a child: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided

pulmonary wedge resection in a child:

a case report

CH Fung, MB, BS, MRCS; CT Lau, MB, BS, FRCS; Kenneth KY Wong, PhD, FRCS

Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CH Fung (fungchiheng@gmail.com)

Case report

Tissue diagnosis of pulmonary nodules of an

undetermined nature can be achieved with

thoracoscopic wedge resection. However, localisation

of a lesion during surgery can be technically

demanding, especially for small deep-seated lesions.

We report our technique of indocyanine green (ICG)

fluorescence-guided pulmonary wedge resection in

a child.

A 4-year-old boy presented with pyrexia of

unknown origin associated with cough for 2 weeks.

Extensive septic workup including sputum culture,

chest X-ray, nasopharyngeal aspirate and urine

culture were unremarkable. Mantoux test was

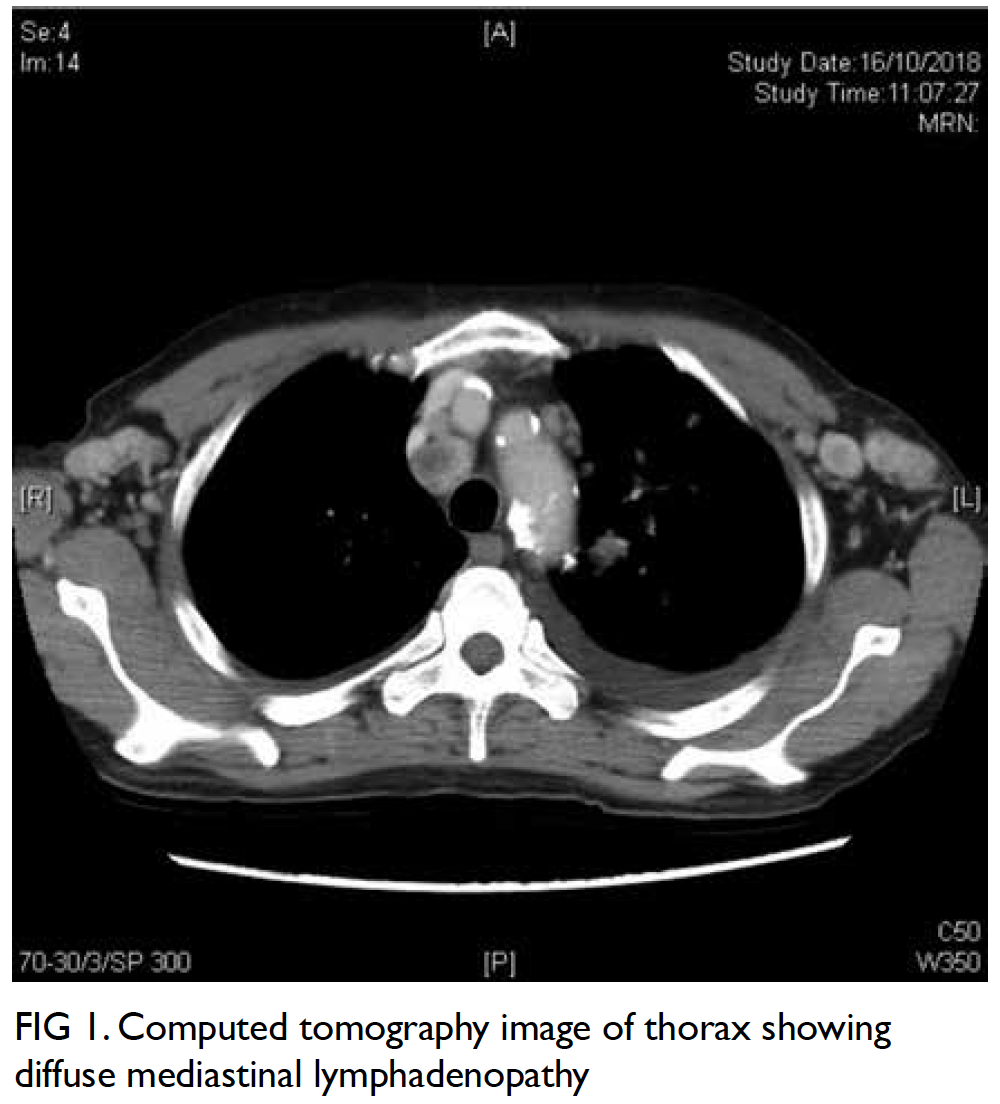

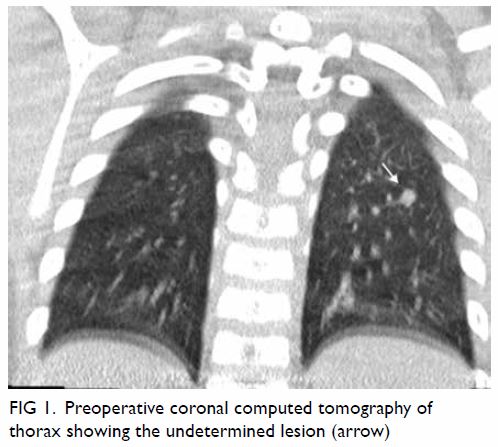

positive. Computed tomographic (CT) scan of the

thorax to look for occult chest infection showed

features suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis and

a 6-mm nodule over the apical segment of the left

lower lobe. He completed a 6-month course of

antitubercular medication but reassessment scan

after 9 months showed a persistent left lower lobe

pulmonary nodule and he was referred to our

surgical unit for tissue diagnosis.

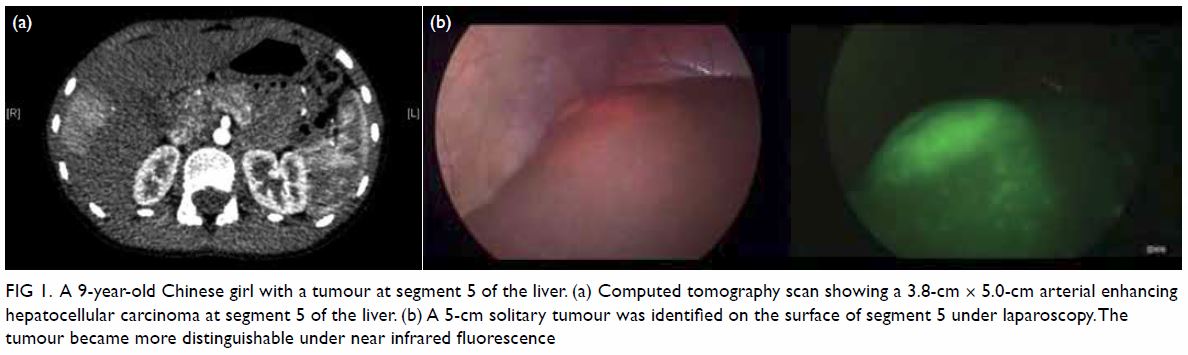

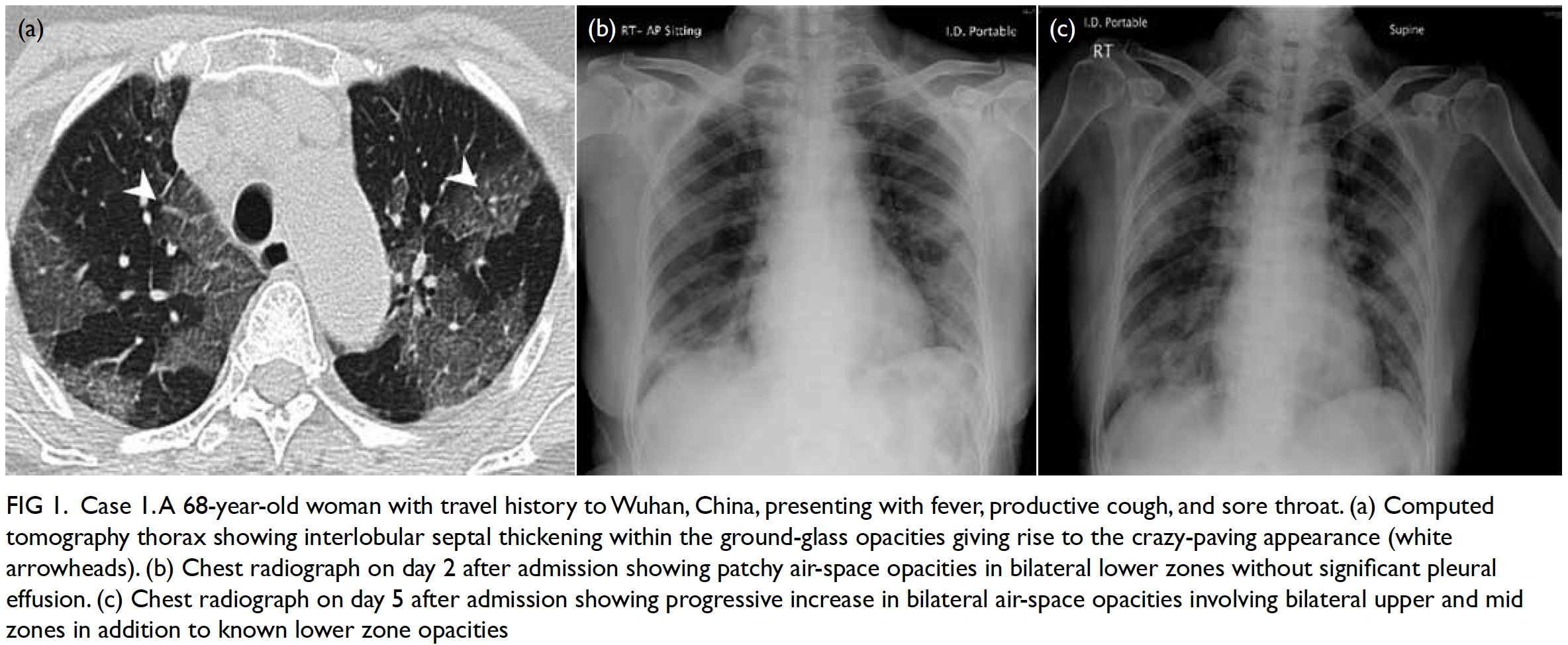

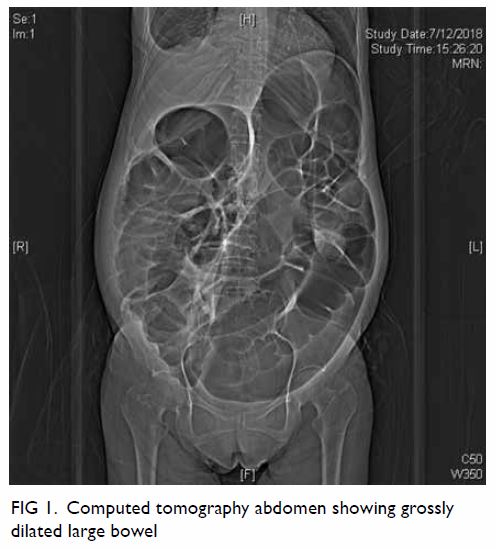

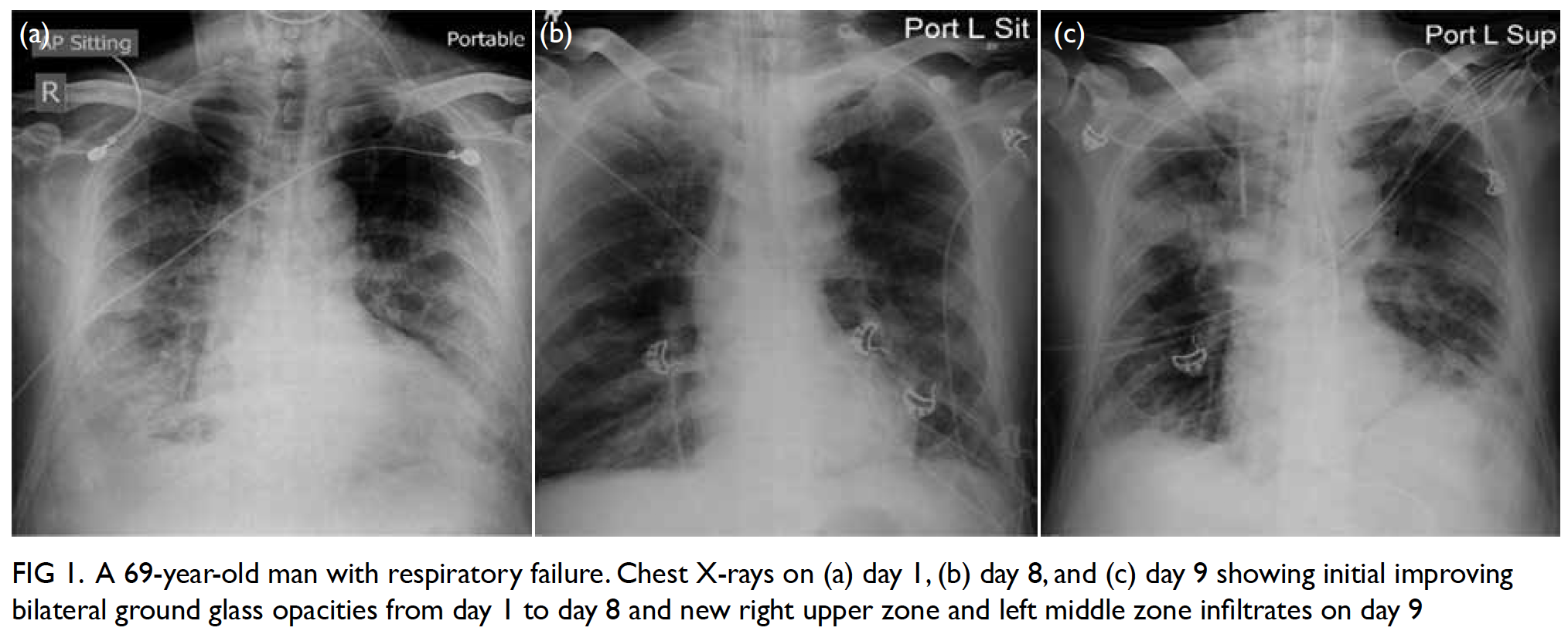

The patient underwent CT-guided localisation

of the pulmonary nodule under general anaesthesia

1 hour prior to thoracoscopic wedge resection.

The pulmonary nodule was identified at the apical

segment of the left lower lobe, 1.3 cm from the

pleural surface (Fig 1). An 18-gauge guiding needle

was inserted by the radiologist to the lesion under

CT guidance. Methylene blue (0.5 mL) and ICG

(0.5 mL) were injected around the lesion via the

guiding needle. A hookwire was also placed for

localisation as safety backup and adjunct to ICG.

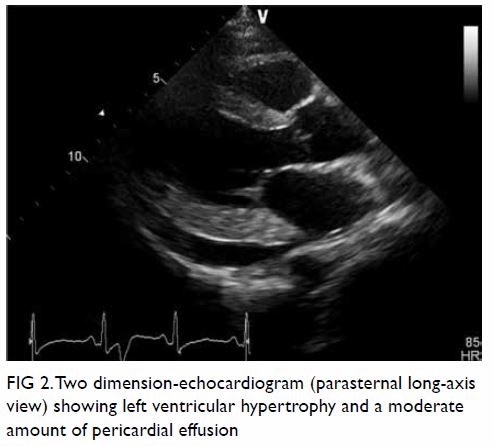

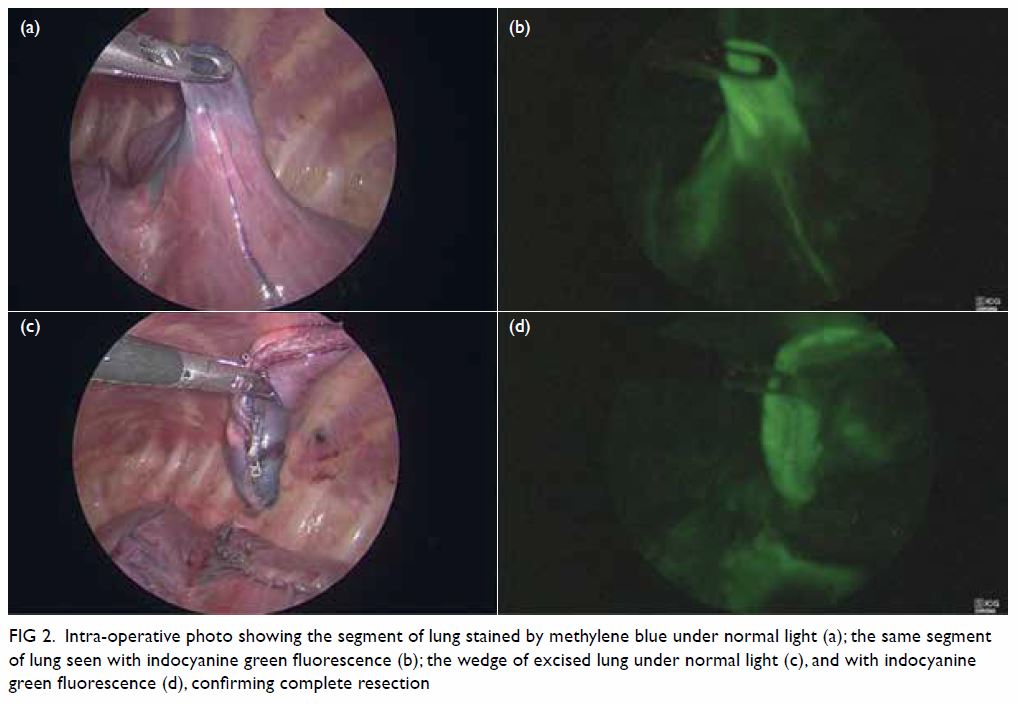

The patient was then transferred back to the

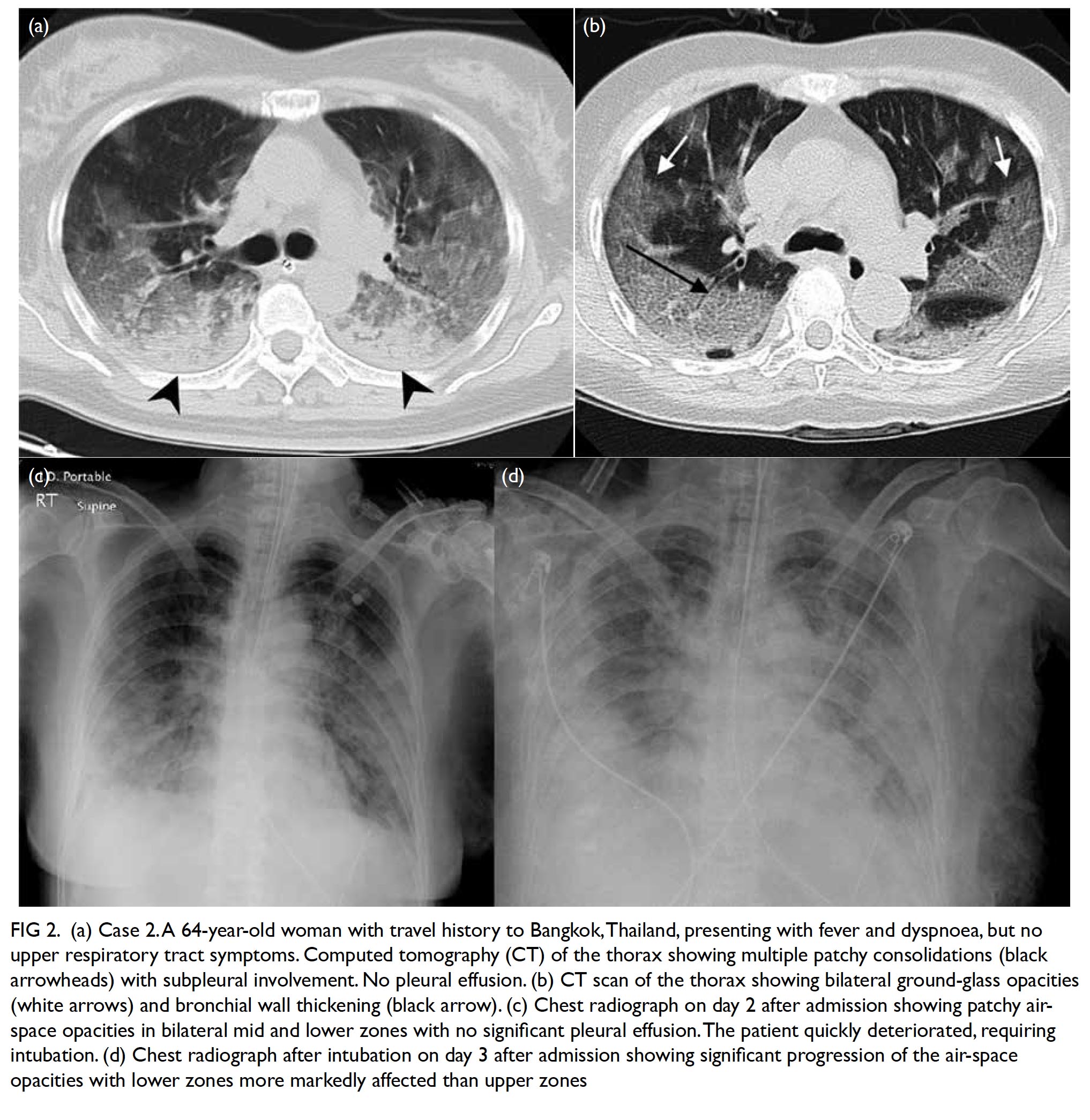

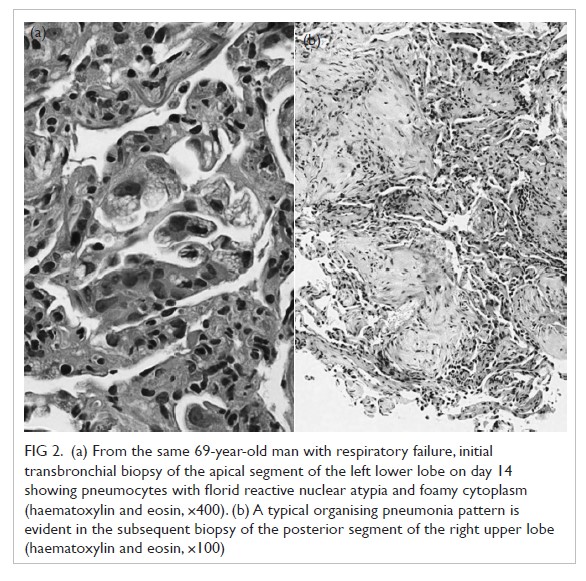

operating theatre. The target lesion was identified

thoracoscopically with guidance of methylene blue

dye and ICG fluorescence (KARL STORZ OPAL1®).

Wedge resection of the target lesion was performed

with Endo GIA™ Ultra Universal 30-mm staplers

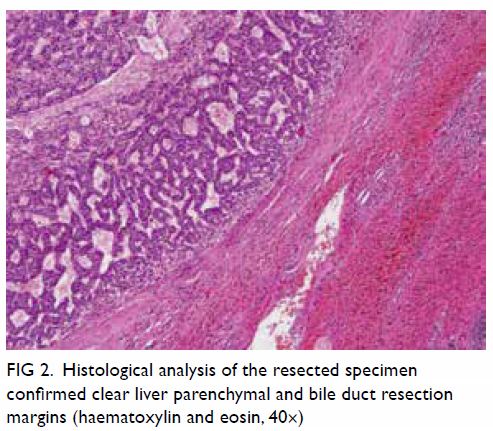

(Medtronic). Complete excision was confirmed by

absence of fluorescence in the remaining left lower

lobe on ICG fluorescence imaging (Fig 2). The use

of ICG fluorescence enhanced intra-operative

localisation of the small pulmonary nodule and facilitated a minimally invasive operation. The patient

made an uneventful recovery and was discharged

2 days after surgery. Histology of the wedge-resected

specimen confirmed complete excision and showed

granulomatous inflammation with focal necrosis and

no evidence of malignancy. The patient had resumed

full activity at follow-up 1 week after surgery.

Figure 1. Preoperative coronal computed tomography of thorax showing the undetermined lesion (arrow)

Figure 2. Intra-operative photo showing the segment of lung stained by methylene blue under normal light (a); the same segment of lung seen with indocyanine green fluorescence (b); the wedge of excised lung under normal light (c), and with indocyanine green fluorescence (d), confirming complete resection

Discussion

Intra-operative localisation of small pulmonary

nodules remains a challenge for prompt and

complete resection of lesions. It is recommended

that preoperative localisation should be performed

prior to minimally invasive resection for pulmonary

nodules <10 mm in diameter or >5 mm from the

pleural surface.1 Various means of preoperative

localisation have been reported in children including

micro-coil insertion, methylene blue dye injection,

and radiotracer labelling.2 Hookwire is reported to

be safe and useful for localisation of lung nodules

in children as well as other situations such as

thoracoscopic resection of deep-seated congenital

cystic adenomatoid malformation.2 3 Although these

methods are considered feasible in children, they

have their own limitations and risks, such as local trauma and issues of inaccuracy in small lesions

for hookwire localisation; difficulty in revealing

deep lesions and diffuse spillage in small lesions of

methylene blue dye. Efforts have been made to find

a convenient, safe, and clear method for localisation.

The United States Food and Drug

Administration has recently extended the approved

uses of ICG to include sentinel lymph node biopsy

in various types of tumour, assessment of blood

supply in anastomosis and reconstructive flaps and

enhanced visualisation of biliary anatomy during

laparoscopic cholecystectomy.4 In thoracic surgery,

it is a useful aid to sentinel lymph node mapping,

lung mapping, oesophageal conduit vascular

perfusion, and lung nodule identification.5 To date,

no data about the use of ICG in thoracoscopic wedge

resection in paediatric patients have been reported.

In our experience, ICG preoperative localisation is a

safe and feasible means to help achieve prompt and

complete thoracoscopic wedge resection of small

pulmonary nodules. It appeared to be more accurate

than hookwire localisation in this patient, allowing

immediate clear visualisation when guiding the

extent of resection. It also facilitated easy assessment

of completeness of resection.

In conclusion, ICG fluorescence is a safe and

feasible method of localisation prior to thoracoscopic

wedge resection of a pulmonary nodule in children.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KKY Wong was not involved in

the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written informed consent for

all procedures.

References

1. Suzuki K, Nagai K, Yoshida J, et al. Video-assisted

thoracoscopic surgery for small indeterminate pulmonary

nodules: indications for preoperative marking. Chest

1999;115:563-8. Crossref

2. Polites SF, Fahy AS, Sunnock WA, et al. Use of radiotracer labeling of pulmonary nodules to facilitate excisional

biopsy and metastasectomy in children with solid tumors.

J Pediatr Surg 2018;53:1369-73. Crossref

3. Lau CT, Wong KK. Thoracoscopic resection of congenital

cystic adenomatoid malformation in a patient with

fused lung fissure using hookwire. Innovations (Phila)

2018;13:226-9. Crossref

4. Namikawa T, Sato T, Hanazaki K. Recent advances in

near-infrared fluorescence-guided imaging surgery using

indocyanine green. Surg Today 2015;45:1467-74. Crossref

5. Okusanya OT, Hess NR, Luketich JD, Sarkaria IS. Infrared

intraoperative fluorescence imaging using indocyanine

green in thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg

2018;53:512-8. Crossref