Novel diaphragmatic reconstruction technique for recurrent diaphragmatic hernia: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Novel diaphragmatic reconstruction technique

for recurrent diaphragmatic hernia: a case report

Teddy HY Wong, MRCS; Simon CY Chow, FRCS; Peter SY Yu, MRCS; Jacky YK Ho, FRCS; Rainbow WH Lau, FRCS; Innes YP Wan, FRCS; Randolph HL Wong, FRCS

Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Randolph HL Wong (wonhl1@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Case report

A 51-year-old lady with a history of congenital

diaphragmatic hernia repair during infancy

presented to the emergency department with

increasing abdominal pain and repeated vomiting.

Posteroanterior chest plain radiograph revealed

dilated small bowel loops in the right thoracic cavity.

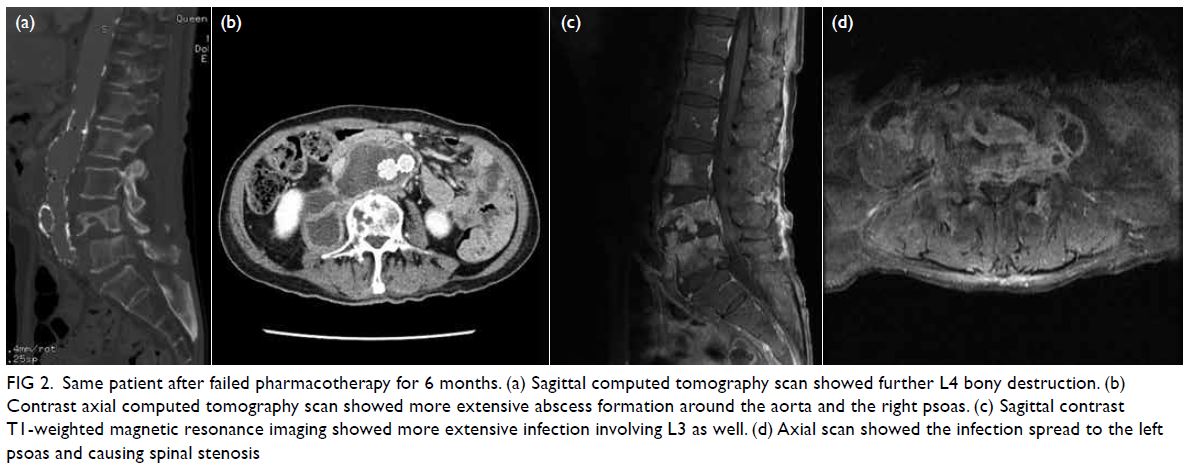

Computed tomography scan revealed two closely

related small bowel loops trapped within a narrow

hernia neck orifice across the diaphragm, suggestive

of closed loop intestinal obstruction (Fig 1). Blood

test results revealed metabolic acidosis and elevated

lactate level.

Emergency laparotomy via a subcostal

incision revealed a right-sided large diaphragmatic

defect with bowel herniating into the thoracic

cavity. Transabdominal reduction of the bowel was

difficult owing to adhesion of bowel to the lung

so an additional posterolateral thoracotomy was

performed by a cardiothoracic team. Adhesiolysis

was performed and the small bowel freed and

reduced to the abdominal cavity via the transthoracic

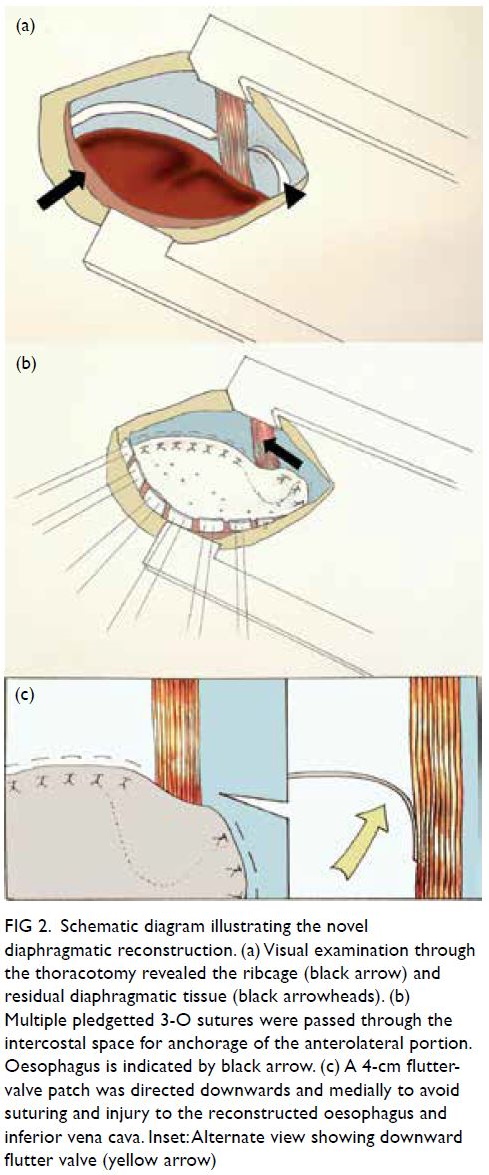

approach. Examination through the thoracotomy

revealed minimal residual diaphragmatic tissue

(Fig 2a). Primary closure was not possible and repair

with a patch posed a technical challenge in the

absence of sufficient residual diaphragmatic tissue

to enable secure anchorage. For the anterolateral

portion, multiple pledgetted 3-O sutures were

passed through the intercostal space for anchorage

(Fig 2b). A neo-diaphragm was reconstructed

using a porcine dermal collagen implant of size

150 mm × 200 mm × 1 mm (PermacolTM; Medtronic,

Minneapolis [MN], United States). The patch was

then parachuted down to cover the defect and

secured. A 4-cm flutter-valve patch was directed

downwards and medially to avoid suturing and

injury to the oesophagus and inferior vena cava

(Fig 2c). We believe this design permits peristalsis of

oesophageal content without causing stricture while

also preventing future intestinal herniation.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram illustrating the novel diaphragmatic reconstruction. (a) Visual examination through the thoracotomy revealed the ribcage (black arrow) and residual diaphragmatic tissue (black arrowheads). (b) Multiple pledgetted 3-O sutures were passed through the intercostal space for anchorage of the anterolateral portion. Oesophagus is indicated by black arrow. (c) A 4-cm flutter-valve patch was directed downwards and medially to avoid suturing and injury to the reconstructed oesophagus and inferior vena cava. Inset: Alternate view showing downward flutter valve (yellow arrow)

Postoperatively the patient was prescribed

total parenteral nutrition for 10 days and gradually

tolerated a normal diet. A computed tomography

scan at 10 days after surgery confirmed an intact neo-diaphragm with no recurrence of hernia. The

patient was discharged home 13 days after surgery.

She was well at follow-up examinations at 1 month

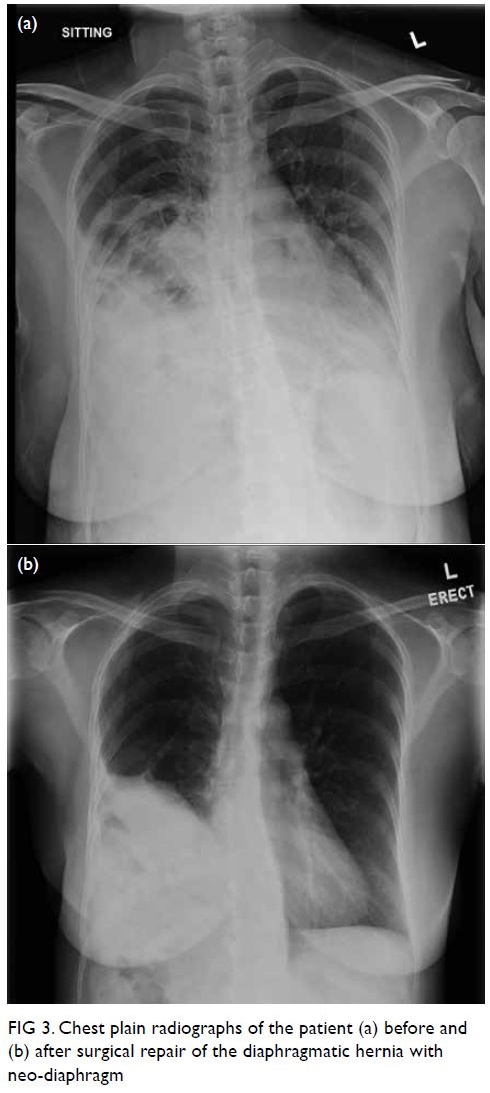

and 12 months after surgery. Chest plain radiograph

confirmed no recurrence of hernia (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Chest plain radiographs of the patient (a) before and (b) after surgical repair of the diaphragmatic hernia with neo-diaphragm

Discussion

Diaphragmatic hernia is a rare but serious condition

associated with respiratory and gastrointestinal

complications and increased mortality.

Surgical repair is the gold standard treatment

to prevent complications. However, patients with a

previously repaired congenital diaphragmatic hernia

are more prone to respiratory complications during

childhood and occasionally develop recurrences.1

However, the long-term success rate of repair is

good with patients surviving well into adulthood

with a normal life expectancy.

Surgical options for repair include a primary repair and a patch repair. A patch repair is associated

with higher risks of complications and recurrence.2

However, for a hernia with large defects in which a primary repair is not possible, repair with surgical

mesh (xenograft or synthetic) is an effective and

safe method.3 In conventional patch repair, the

hernia sac is repositioned and resected. The hernia

defect is sized and the Permacol trimmed to cover

the defect. The flap is then fixed to the remaining

rim of diaphragmatic tissue with absorbable

sutures.4 The lack of an adequate rim of tissue

in our patient presented a unique challenge for

construction of the neo-diaphragm relative to

most instances of diaphragmatic hernia where

a remnant of diaphragmatic tissue is present for

anchorage. Although the pleura and adjacent

chest wall offer good support for anchoring the neo-diaphragm posteriorly and anterolaterally,

there is often a lack of strong tissue medially with

consequent substantial risk of inadvertent injury

to the oesophagus if sutures are placed too deeply.

Travers et al5 reported an incidence of oesophageal

injury up to 3.9% in their series of surgical repair

of para-oesophageal hernia using porcine dermal

collagen biologic mesh (Permacol). Innovative

designs in the creation of the neo-diaphragm have

been reported, but most studies have been in

paediatric patients.6 The technique described in

this case report is novel and has not been reported

elsewhere. The design of a flutter valve mechanism

in the reconstruction of the medial aspect of the

neo-diaphragm serves to create a tension-free repair

near the mediastinum and oesophagus while also

creating a seal to separate the pleural cavity from the

abdominal contents. No sutures were applied near the

oesophagus or the medial side of the neo-diaphragm.

This technique avoids inadvertent visceral injury

and is currently our preferred technique of neo-diaphragm

construction in patients with a large

diaphragmatic defect and insufficient rim.

In our case, we utilised the acellular dermal

matrix Permacol for hernia repair. Permacol is a

cross-linked graft comprised of acellular collagen

matrix. Compared with other collagen-based

implants, it offers long-lasting dimensional stability

and avoids loss of tensile strength as well as increased

tissue laxity resulting in lower rates of recurrence.

Acellular dermal matrix is a developing technology

and studies have shown promising results for its

efficacy.7

In conclusion, repair of diaphragmatic hernia

with a xenograft composed of dermal collagen

implant and a medial flutter-valve design is safe and

effective. It avoids inadvertent injury to mediastinal

structures while allowing satisfactory prevention of

recurrence of diaphragmatic herniation of intestines.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: THY Wong, SCY Chow, RHL Wong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: THY Wong, SCY Chow, RHL Wong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided written

informed consent for all treatments and procedures and

consent for publication.

References

1. Jancelewicz T, Chiang M, Oliveira C, Chiu PP. Late surgical

outcomes among congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH)

patients: why long-term follow-up with surgeons is

recommended. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:935-41. Crossref

2. Jancelewicz T, Vu LT, Keller RL, et al. Long-term surgical

outcomes in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: observations

from a single institution. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:155-60. Crossref

3. Kuhn R, Schubert D, Wolff St, Marusch F, Lippert H,

Pross M. Repair of diaphragmatic rupture by laparoscopic

implantation of a polytetrafluoroethylene patch. Surg

Endosc 2002;16:1495. Crossref

4. Lingohr P, Galetin T, Vestweber B, Matthaei H, Kalff JC,

Vestweber KH. Conventional mesh repair of a giant

iatrogenic bilateral diaphragmatic hernia with an

enterothorax. Int Med Case Rep J 2014;7:23-5. Crossref

5. Travers HC, Brewer JO, Smart NJ, Wajed SA.

Diaphragmatic crural augmentation utilising cross-linked

porcine dermal collagen biologic mesh (Permacol) in the

repair of large and complex para-oesophageal herniation: a

retrospective cohort study. Hernia 2016;20:311-20. Crossref

6. Loff S, Wirth H, Jester I, et al. Implantation of a cone-shaped

double-fixed patch increases abdominal space

and prevents recurrence of large defects in congenital

diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:1701-5. Crossref

7. Buinewicz B, Rosen B. Acellular cadaveric dermis

(AlloDerm): a new alternative for abdominal hernia repair.

Ann Plast Surg 2004;52:188-94. Crossref