© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Multifocal mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

involving the lungs and the stomach: a rare clinical entity: a case report

Carla PM Lam, MB, BS1; CF Wong, FHKCP,

FRCP (Edin)2

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Tuberculosis and Chest Medicine Unit,

Grantham Hospital, Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CF Wong (meicarlalam@gmail.com)

Case report

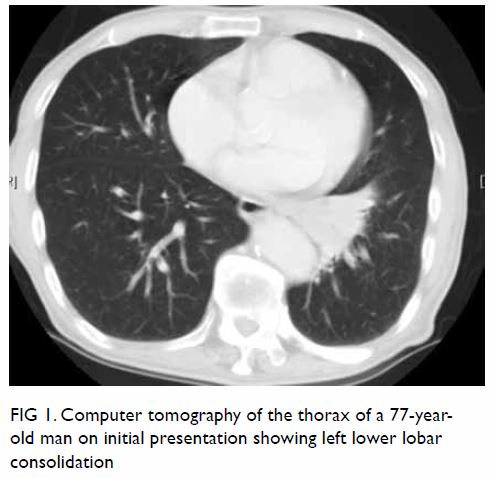

A 77-year-old male ex-smoker initially presented to

Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong in April 2009 with an abnormal lung lesion

at the left lower lobe on computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen

during workup for abdominal aorta aneurysm (Fig 1). The lung lesion persisted despite antibiotic

treatment. Flexible bronchoscopy, bronchial brushings and aspirate were

unremarkable. It was decided to keep the patient under observation.

Figure 1. Computer tomography of the thorax of a 77-year-old man on initial presentation showing left lower lobar consolidation

One year later he developed per-rectal bleeding.

Colonoscopy was unremarkable but upper endoscopy revealed a 5-cm

ulcerative growth in the posterior wall of the proximal gastric body.

Histology showed sheets of small abnormal lymphoid cells with pale

cytoplasm and cleaved nuclear outline, strongly positive for CD20 and

CD79a, and negative for CD3, CD5, CD23, CD10, CD43, and Cyclin-D1. There

was lambda light chain restriction. The Ki-67 proliferation index was less

than 10%. Lymphoepithelial lesions were identified. Helicobacter pylori

was not detected and the patient was treated as a case of isolated primary

H pylori–negative gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)

lymphoma with H pylori eradication followed by rituximab for eight

cycles. The response was suboptimal and he was subsequently prescribed

three cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and

prednisolone.

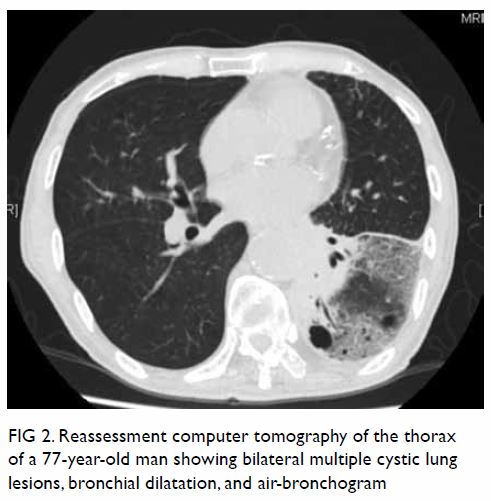

He was admitted to our chest unit in July 2017 for

treatment of chest infection. Review of serial chest X-ray and CT scans

showed progressive deterioration of the lung lesion that had extended to

the whole left lower lobe with consolidative changes, air bronchogram,

multiple cystic changes and bronchial dilatation (Fig 2). Serial positron emission tomography–CT scans

showed that the lung lesion was metabolically active with partial

improvement upon chemotherapy correlating with that of the gastric MALT

lymphoma. Repeat fibre-optic bronchoscopy and transbronchial lung biopsy

revealed respiratory mucosa with diffuse dense lymphoid proliferation in

the stroma. Lymphoepithelial lesions were again observed, positive for

CD20 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, CD23, and Cyclin-D1. Lambda light

chain restriction was demonstrated, compatible with MALT lymphoma.

Figure 2. Reassessment computer tomography of the thorax of a 77-year-old man showing bilateral multiple cystic lung lesions, bronchial dilatation, and air-bronchogram

Discussion

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma is a

relatively rare disease with an annual incidence estimated at 1/313 000;

MALT lymphoma accounts for 6% to 8% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Histologically, MALT lymphoma is characterised by neoplastic cell

infiltration around reactive secondary lymphoid follicles in a marginal

zone distribution and centrocyte-like cells that are small-to-medium in

size with small irregular nuclei. Neoplastic cells frequently have

abundant pale cytoplasm and a distinct cell border, resembling small

mature lymphocytes. Lymphoepithelial lesions have been frequently

described. The immunophenotype of MALT lymphoma is virtually identical to

that of non-neoplastic marginal-zone B cells. They are positive for CD20

but negative for IgD, CD5, CD10, Bcl6, and Cyclin-D1. Demonstration of

immunoglobulin light chain restriction is also helpful to exclude reactive

lymphoid infiltrate. No specific immunohistochemical marker has been

identified for MALT lymphoma with different tissues of origin.1

The most common site of involvement of MALT

lymphoma is the stomach, accounting for half of all cases. Other sites

include the small intestine (20%-30%), colon (10%), salivary glands,

thyroid, lung, bladder, and skin. Gastric MALT lymphoma is strongly

associated with H pylori that has been implicated in its

pathogenesis. The majority (92%-98.3%) of gastric MALT lymphomas are

positive for H pylori, and H pylori eradication alone

achieves complete remission of gastric MALT lymphoma in 80% of cases.

Pulmonary MALT lymphoma is a very rare condition,

accounting for aproximately 1% of cases. Pulmonary MALT lymphoma is

usually an indolent disease and has no association with H pylori

but is associated with chronic inflammatory conditions instead.

Radiological features of pulmonary MALT lymphoma are diverse and include

air bronchogram, bronchial dilation, nodular lesions, lung mass,

ground-glass opacities, and cystic lung lesions. Lesions are likely

multiple, bilateral without lobar predilection with maximum standardised

uptake value varying from 2.8 to 9.4.2

Although MALT lymphoma was once thought to be an

indolent disease due to its tendency to remain localised for a prolonged

period to the tissue of origin, multifocal involvement of MALT lymphoma at

presentation has been increasingly reported in recent years.3 4 In a case

series of 304 patients with MALT lymphoma in Japan,3 seven (2%) had multifocal involvement, mostly involving

the gastrointestinal tract. In another case series in Austria involving 72

patients with non-gastric MALT lymphoma, 23 (32%) had multifocal disease

either on presentation or during the study period. Site-specific

involvement was reported. The stomach was involved at staging upper

endoscopy and histologically confirmed (P<0.0001) in seven of 13

patients with primary lung MALT lymphoma.4

There are no specific histological or

immunostaining characteristics for MALT lymphoma at different sites.

Sequence analysis of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IgH) may help

demonstrate multifocality of MALT lymphoma. In a study that recruited 170

patients with MALT lymphoma over 8 years, 11 had multifocal involvement

and paired tumour biopsy samples were analysed in four.5 Monoclonal rearrangement of the IgH gene was detected

in all four tumour pairs of which three had different VDJ sequences,

indicating that there was no clonal relationship between the tumour pairs

whereas the fourth demonstrated clonal identity. That study implied that

MALT lymphomas involving different organ systems more often represent

different clones and arise independently instead of disseminating from one

system to another.5

In our case, we believe that the MALT lymphoma was

multifocal in origin and the pulmonary lesion preceded that of the stomach

based on the temporal sequence (appearance of lung lesion long before

clinical manifestation of gastric MALT lymphoma). Further analysis of the

VDJ sequence of the IgH of the tumour samples is needed to demonstrate the

clonal relationship between them.

Conclusion

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma was once

thought to be an indolent disease localised to one tissue origin, but

occurrence of multifocal disease has been increasingly reported. Our case

illustrates multifocal MALT lymphoma involving the lungs and the stomach

with classic histology, radiological features, and clinical behaviour.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquistition of data: CPM Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CPM Lam.

Drafting of the manuscript: CPM Lam.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquistition of data: CPM Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CPM Lam.

Drafting of the manuscript: CPM Lam.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have disclosed no conflict of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided

verbal informed consent.

References

1. Bacon CM, Du MQ, Dogan A.

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a practical guide for

pathologists. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:361-72. Crossref

2. Zhang WD, Guan YB, Li CX, Huang XB,

Zhang FJ. Pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: computed

tomography and 18F fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission

tomography/computed imaging findings and follow-up. J Comput Assist Tomogr

2011;35:608-13. Crossref

3. Yoshino T, Ichimura K, Mannami T, et al.

Multiple organ mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas often involve

the intestine. Cancer 2001;91:346-53. Crossref

4. de Boer JP, Hiddink RF, Raderer M, et

al. Dissemination patterns in non-gastric MALT lymphoma. Haematologica

2008;93:201-6. Crossref

5. Konoplev S, Lin P, Qiu X, Medeiros LJ,

Yin CC. Clonal relationship of extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue involving different sites. Am J Clin

Pathol 2010;134:112-8. Crossref