© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Lysergic acid diethylamide–associated intoxication in

Hong Kong: a case series

C Li, MB, BS1,2; Magdalene HY Tang, PhD1;

YK Chong, FHKCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)1,2; Tina YC

Chan, MB, ChB, PhD1,2; Tony WL Mak, FRCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)1,2

1 Hospital Authority Toxicology

Reference Laboratory, Hong Kong

2 Chemical Pathology Laboratory,

Department of Pathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Tony WL Mak (makwl@ha.org.hk)

Case series

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is a powerful

hallucinogenic drug that was first synthesised in 1938.1 Although LSD is considered a conventional drug of

abuse, cases of LSD intoxication are scarce in Hong Kong. The Hospital

Authority Toxicology Reference Laboratory—the only tertiary referral

laboratory for toxicological analysis in Hong Kong, established in

2004—did not encounter cases of LSD intoxication until 2015. Between 2015

and 2018, eight cases of LSD-associated intoxication were identified at

five acute hospitals in Hong Kong when LSD and its metabolites were

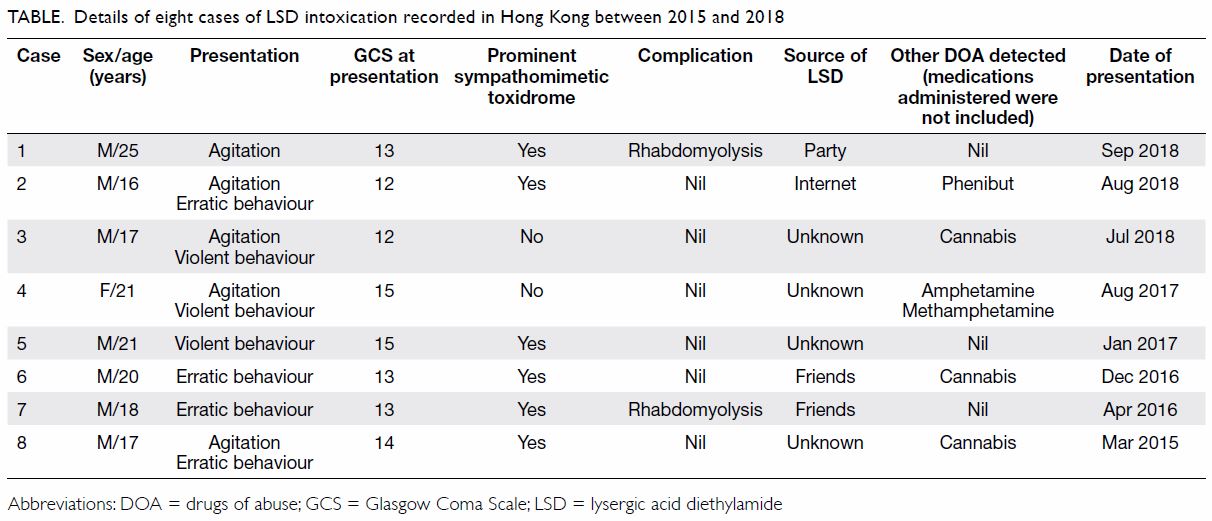

detected in patient urine samples. Details of these eight patients (7

male, 1 female; age range, 16-25 years) are presented in the Table.

The most common presentation of LSD intoxication in these patients was

agitation (63%), followed by erratic behaviour (50%) and violent behaviour

(38%). Impaired level of consciousness (75%) and apparent sympathomimetic

toxidrome (75%) were documented in most patients. History of LSD use was

elicited in all cases. However, only four patients were willing to

volunteer the sources of LSD: one bought LSD from the Internet, one

obtained LSD at a party, and two obtained LSD from friends. The most

common co-ingestant was cannabis, which was detected in three cases.

Amphetamine and methamphetamine were detected in one case. In one patient,

phenibut (3-phenyl-4-aminobutyric acid), a central nervous system

depressant structurally related to gamma-aminobutyric acid, was detected.

Two cases were complicated by rhabdomyolysis and one of them required

intensive care unit admission. The clinical details of these two cases are

presented below.

Case 1

A 25-year-old man who had a history of childhood

asthma presented to Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong, in September

2018 with agitation after sublingual use of LSD on a stamp at a party. At

presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale was 13/15 (E4, V4, M5). The patient’s

blood pressure was 116/80 mm Hg, heart rate was 150 beats per minute, body

temperature was 39.2℃, and pupil sizes were 5 mm bilaterally. Biochemical

investigations showed a peak creatine kinase (CK) value of 6260 U/L, and

urine myoglobin was positive. The patient was intubated and treated with

alkaline diuresis in the intensive care unit. The urine specimen was

analysed in the Toxicology Reference Laboratory, where LSD, its metabolite

(2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD), diazepam, nordiazepam, temazepam, midazolam and

propofol were detected.

Case 2

An 18-year-old man who enjoyed good past health

presented to United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong, in April 2016 with

erratic behaviour after sublingual use of LSD on a stamp obtained from his

friends. At presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale was 13/15 (E4, V4, M5).

The patient’s blood pressure was 127/50 mm Hg, heart rate was 167 beats

per minute, body temperature was 38.7℃, and pupil sizes were 6 mm

bilaterally. Biochemical investigations showed metabolic acidosis, a peak

CK value of 14 732 U/L, and urine myoglobin was positive. In the urine

specimen, LSD, its metabolite (2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD), and lidocaine were

detected.

Discussion

Classically described as a psychedelic or

hallucinogenic agent, LSD is structurally similar to serotonin

(5-hydroxytryptamine), an important neurotransmitter in the central

nervous system. It acts as a serotonin receptor agonist in the central

nervous system and may produce prominent visual hallucinations,

audiovisual synaesthesia, and derealisation. Significant sympathomimetic

stimulation has also been observed.2

The effects typically begin within 30 to 60 minutes, peak at around 2

hours and can last for up to 12 hours after intake.2 These effects are consistent with the current findings

that most patients presented with apparent sympathomimetic toxidrome,

characterised by tachycardia, hypertension, mydriasis, and pyrexia.

There is a general impression promulgated over the

Internet and by celebrities that LSD is harmless and even beneficial to

personal development. Recently, LSD has re-emerged as a micro-dosing

psychedelic. People consume regular low doses of LSD in an attempt to

boost their creativity.3 However,

this practice, also described as the Silicon Valley trend, lacks

scientific evidence. These factors appear to have misled the public into

underestimating the potential sequelae of LSD abuse. In contrast, our case

series clearly demonstrates that LSD intoxication is associated with

severe sequelae. In both cases complicated with rhabdomyolysis, no other

stimulant-class drugs of abuse were detected, including conventional and

emerging drugs of abuse.4 No better

alterative causes of rhabdomyolysis were identified from the medical or

drug history and biochemical investigations; LSD intoxication was the

major contributing factor to rhabdomyolysis in both cases. Other cases of

LSD-associated rhabdomyolysis have been reported in the literature.5 6 Fortunately,

all patients in our series recovered uneventfully. However, at least one

fatal case has been reported elsewhere.7

Frontline clinicians should be aware that LSD has

re-appeared, disguised as a “safe” drug of abuse associated with multiple

local intoxication cases with severe sequelae including rhabdomyolysis.

Thorough investigations and serial monitoring are required to detect

complications. Urine toxicology is useful to confirm the exposure to drugs

of abuse. However, owing to its high potency, the dosage of LSD taken is

small (in micrograms) and urine levels may be very low.2 A sensitive analytical system is required to detect the

presence of LSD and its metabolite. Public education on the dangers or LSD

abuse, and effective regulatory control by the government sectors are

recommended.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design of study: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: C Li, MHY Tang, TWL Mak.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: C Li, MHY Tang, TWL Mak.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the

Hong Kong Hospital Authority Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics

Committee (Ref KW/EX-19-003). The Committee exempted the study group from

obtaining patient consent.

References

1. Nichols DE, Grob CS. Is LSD toxic?

Forensic Sci Int 2018;284:141-5. Crossref

2. Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Steuer AE, et al.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lysergic acid diethylamide in

healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017;56:1219-30. Crossref

3. Anderson T, Petranker R, Rosenbaum D, et

al. Microdosing psychedelics: personality, mental health, and creativity

differences in microdosers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2019;236:731-40. Crossref

4. Tang M, Ching CK, Tse ML, et al.

Surveillance of emerging drugs of abuse in Hong Kong: validation of an

analytical tool. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:114-23. Crossref

5. Mercieca J, Brown EA. Acute renal

failure due to rhabdomyolysis associated with use of a straitjacket in

lysergide intoxication. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1949-50. Crossref

6. Berrens Z, Lammers J, White C.

Rhabdomyolysis after LSD ingestion. Psychosomatics 2010;51:356-356.e3. Crossref

7. Fysh RR, Oon MC, Robinson KN, Smith RN,

White PC, Whitehouse MJ. A fatal poisoning with LSD. Forensic Sci Int

1985;28:109-13. Crossref