Parosteal lipoma of the scapula: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Parosteal lipoma of the scapula: a case report

L Xu, MB, BS; KH Tsang, MB, BS

Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr L Xu (xl599@ha.org.hk)

Case report

A 59-year-old Chinese man with a history of follicular lymphoma presented in November 2015 with painless swelling in the right upper back. The patient had no history of trauma. Clinical examination revealed a mild non-tender prominence over the right scapula without palpable axillary lymph nodes. Musculoskeletal and neurovascular examinations were normal.

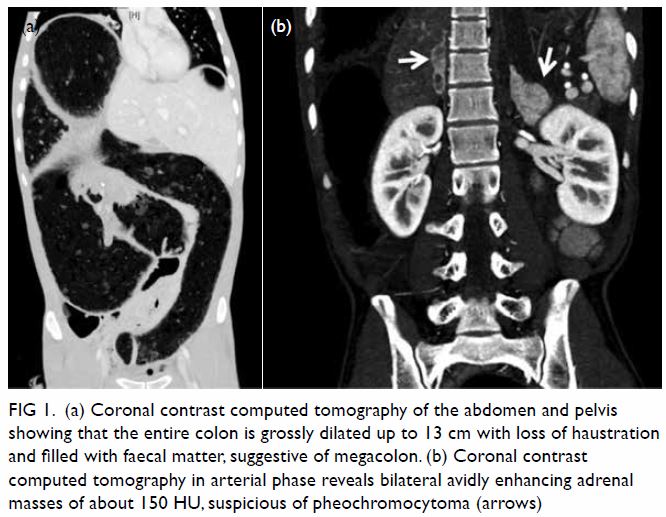

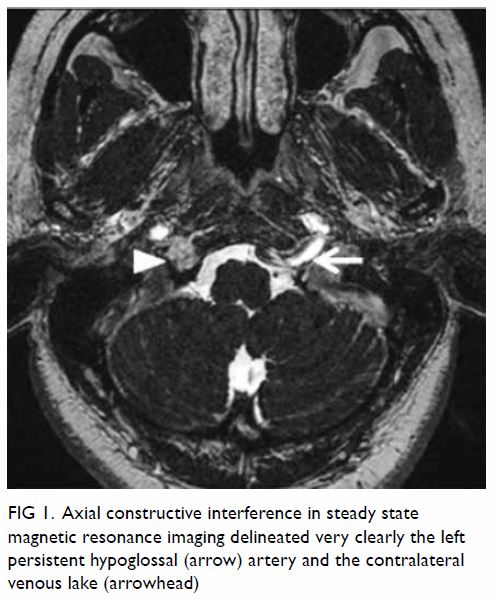

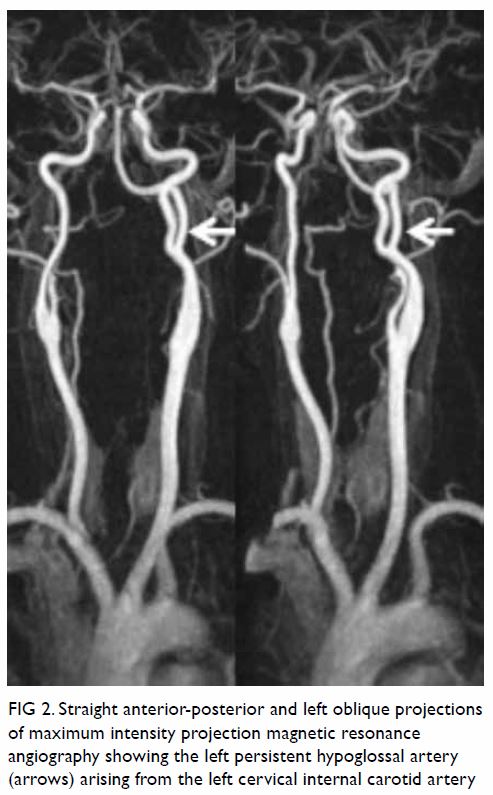

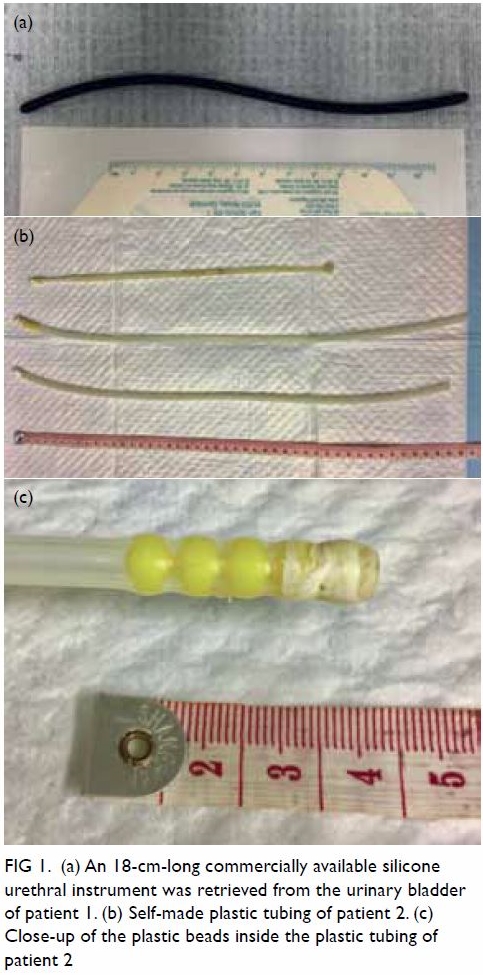

Plain radiograph of the right shoulder showed a well-circumscribed radiolucent lesion in the body of the right scapula with an adjacent irregular osseous protuberance. Computed tomographic scan revealed a well-defined lipomatous subscapular lesion with internal calcific foci adjacent to the body of the scapula with juxtacortical bony excrescence (Fig 1a and b). There was no continuity with the medulla of the parent bone. The provisional diagnosis was lipoma. Because of the history of follicular lymphoma, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scans had been performed at regular intervals for 3 years; these scans incidentally showed a serial increase in the size of the right scapular lesion from 2.5 cm × 3.8 cm to 3.2 cm × 5.8 cm. No significant FDG uptake was seen (Fig 1c).

Figure 1. (a) Coronal computed tomography (CT) of the thorax in soft tissue window and (b) axial CT in bone window showing a well-defined lipomatous subscapular lesion of -111 Hounsfield units with internal calcific foci adjacent to the body of the scapula with juxtacortical bony excrescence (arrow). (c) Axial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–CT scan showing the same lesion without significant FDG uptake (arrow)

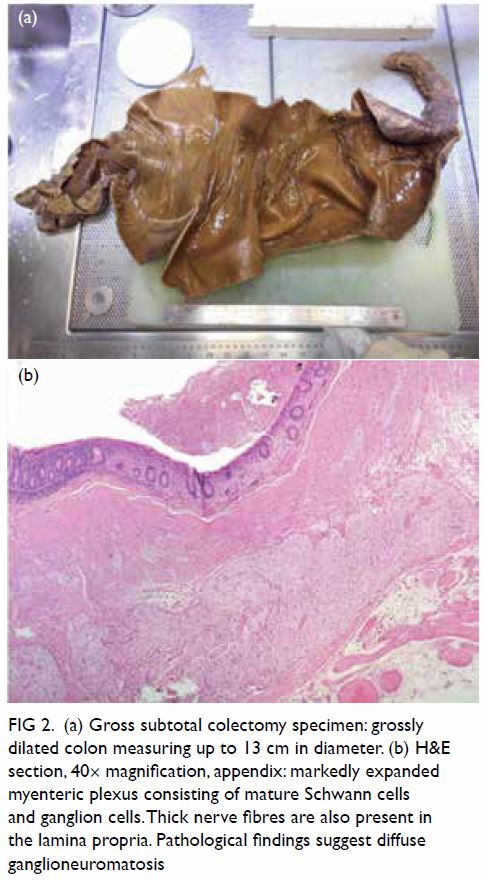

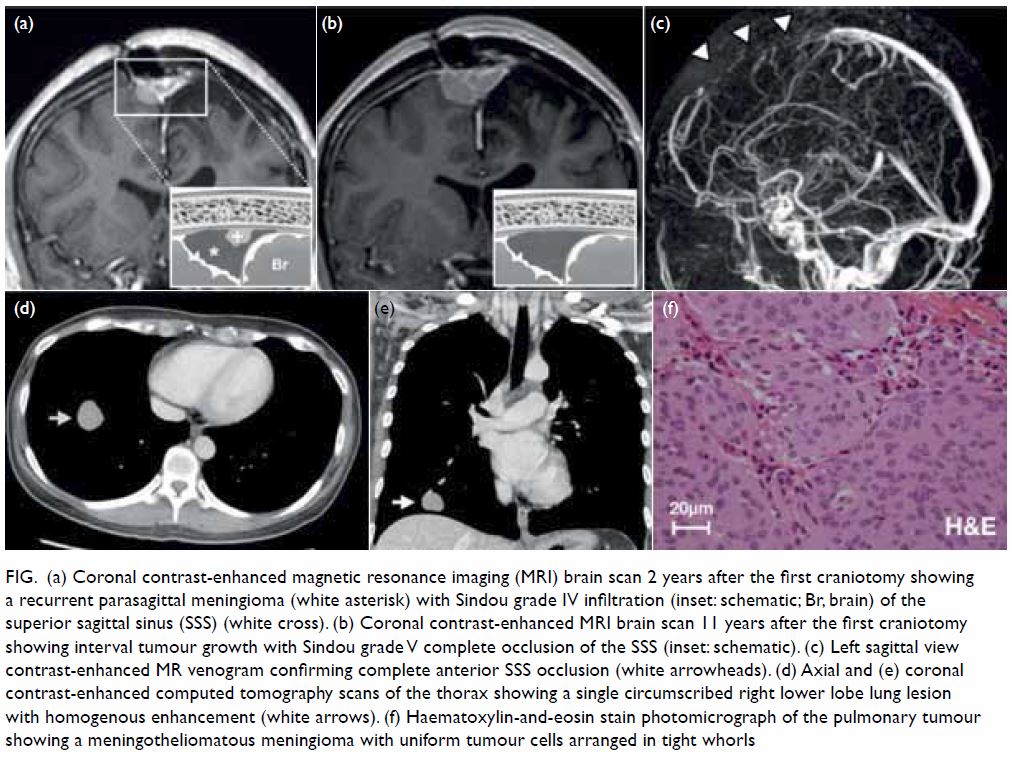

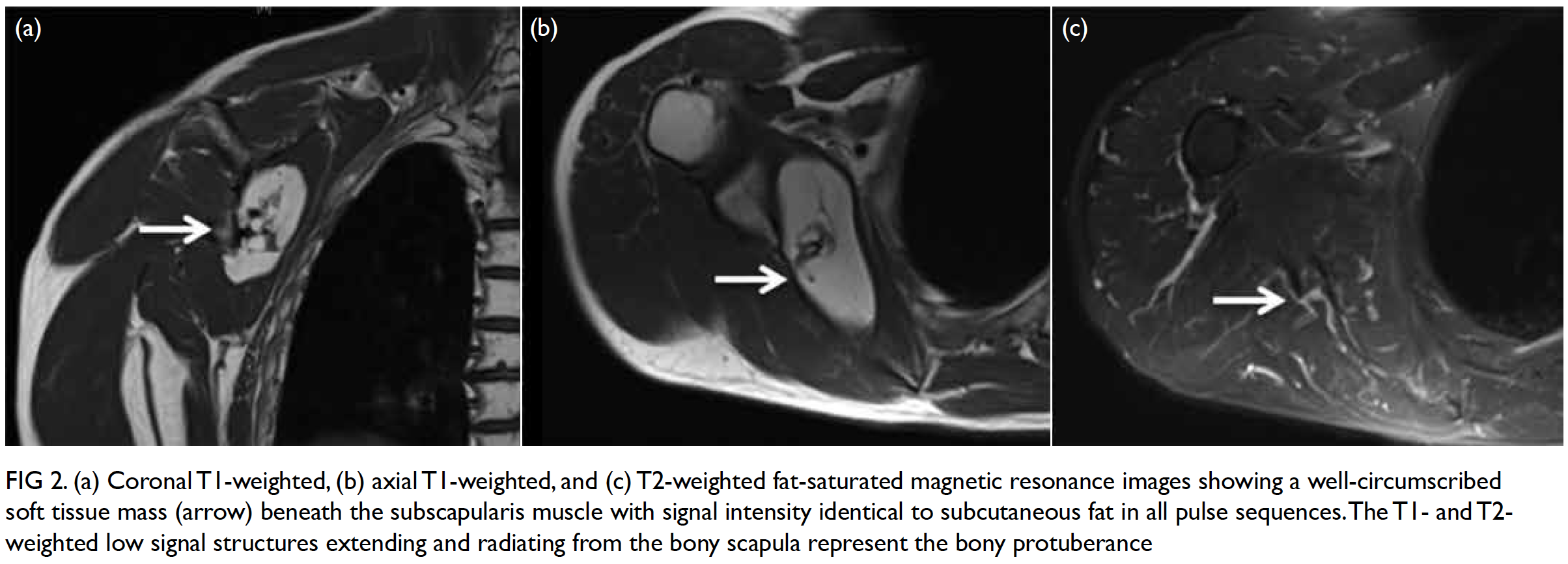

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed for further characterisation showed a well-marginated 3.2-cm × 7.6-cm × 6.6-cm soft tissue mass beneath the subscapularis muscle abutting the subscapularis fossa (Fig 2). Signal intensity was predominantly identical in all pulse sequences to that of subcutaneous fat, suggestive of a lipomatous component. The central part of the lesion was heterogeneous in signal intensity, with T1-weighted and T2-weighted low signal structures extending and radiating from the bony scapula, corresponding to the bony protuberance seen on CT scan. Thin internal septa were noted within the lesion. No cortical or medullary continuation with the parent bone was evident. There was no gross invasion of the bony scapula. No muscle atrophy was seen to suggest nerve entrapment.

Figure 2. (a) Coronal T1-weighted, (b) axial T1-weighted, and (c) T2-weighted fat-saturated magnetic resonance images showing a well-circumscribed soft tissue mass (arrow) beneath the subscapularis muscle with signal intensity identical to subcutaneous fat in all pulse sequences. The T1- and T2-weighted low signal structures extending and radiating from the bony scapula represent the bony protuberance

While the imaging features were compatible with that of a parosteal lipoma, CT-guided biopsy of the lesion was subsequently performed for confirmation. Under local anaesthesia and CT guidance, the right scapular body was penetrated via a posterior approach through the infraspinatus muscle and the parosteal lipomatous tumour in the subscapular fossa was biopsied multiple times.

Pathology examination showed tissue mainly consisting of mature fat cells interspersed by thin fibrous septa. Cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei were not seen. Some bony fragments were seen. Findings were consistent with a parosteal lipoma. Conservative management was decided in view of the deep-seated location of the lesion. Follow-up MRI scan showed no significant interval change.

Discussion

Although lipoma is a common benign tumour of mature adipose tissue, which can occur in almost any organ, parosteal lipoma is a rare type of lipoma, accounting for 0.3% of all lipomas.1 Parosteal lipoma is contiguous to the periosteum and is most commonly found near the diaphysis or diametaphysis of the long bones, in particular the femur and proximal radius, and less commonly the tibia, humerus, scapula, clavicle, ribs, pelvis, metacarpals, metatarsals, and mandible.1 2 The scapula is considered a rare site of involvement with only a few cases reported in the literature.

First described by Seering in 1836,3 the term "periosteal lipoma" is strictly defined as a lipoma originating from the periosteum. The term "parosteal lipoma" was coined by Power in 18884 to emphasise that the lesion is adjacent to the bone but does not necessarily arise from it since the periosteum contains no fat cells.

Parosteal lipoma patients, aged 40 to 60 years, usually present with a history of a slow-growing, large, painless, non-tender immobile mass that is not fixed to the skin.5 Motor or sensory deficits from nerve compression caused by parosteal lipomas are common compared with other lipomatous lesions and are most frequently associated with forearm lesions affecting the posterior interosseous nerve.6

The imaging features of parosteal lipoma are usually characteristic. In a study of 32 cases of parosteal lipoma by Fleming et al,1 nearly 70% of patients had abnormal underlying bone and 50% had osseous reaction, both seen in our patient. The most frequent osseous reactive changes, as can be demonstrated in radiograph and CT studies, include bony protuberance, bowing of bone, or cortical pressure erosion secondary to the adjacent lipomatous mass.1 These cortical abnormalities do not display medullary or cortical continuity with the underlying bone.

As illustrated in our case, on MRI images, parosteal lipoma is identified as a juxtacortical mass with signal intensity identical to that of subcutaneous fat, regardless of pulse sequences. T1- and T2-weighted hypointense areas represent osseous components. Areas with intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images that are high signal intensity on T2-weighted images represent the cartilaginous components of parosteal lipoma.7 Fibrovascular septa may cause a lobulated appearance of the fat component, with low-signal-intensity strands on T1-weighted images that become higher in signal intensity on the long TR images, especially with fat suppression. Adjacent muscle atrophy is identified as increased striations of fat in the affected muscle and is caused by associated nerve entrapment.7

Although there are no reports of malignant transformation, the treatment of choice for parosteal lipoma is complete surgical excision before irreversible muscle atrophy takes place, especially in cases with nerve entrapment. Parosteal lipomas are characteristically encapsulated and strongly adherent to the underlying periosteum, particularly at sites with osseous proliferation. This often requires subperiosteal dissection or segmental resection of bone.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of the study, acquisition and analysis of the data, drafting of the article, and critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr LM Kwok from Queen Elizabeth Hospital for her pathology input.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all procedures.

References

1. Fleming RJ, Alpert M, Garcia A. Parosteal lipoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1962;87:1075-84.

2. Previgliano CH, Sangster GP, Simoncini AA, et al. Parosteal lipoma of the rib: a benign condition that mimics malignancy. J La State Med Soc 2010;162:40-3.

3. Seering G. Geschichte eines sehr grossen steatoms im hinterhaupte eines 2 und 1/2 jahrigen kindes [in German]. Mag Ges Heil 1836;511-4.

4. Power D. A parosteal lipoma, or congenital fatty tumor, connected with the periosteum of the femur. Trans Pathol Soc (London) 1888;39:270-2.

5. Ramos A, Castello J, Sartoris DJ, Greenway GD, Resnick D, Haghighi P. Osseous lipoma: CT appearance. Radiology 1985;157:615-9. Crossref

6. Moon N, Marmor L. Parosteal lipoma of the proximal part of the radius: a clinical entity with frequent radial-nerve injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1964;46:608-14. Crossref

7. Murphey MD, Johnson DL, Bhatia PS, Neff JR, Rosenthal HG, Walker CW. Parosteal lipoma: MR imaging characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;162:105-10. Crossref