Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Differentiating episodic ataxia type 2 from

migraine: a case report

HJ Wu, MRCPCH1; WL Lau, FHKAM (Paediatrics), FHKCPaed1; Tina YC Chan, MB, ChB2; Sammy PL Chen, FHKAM (Pathology), FHKCPath2; CH Ko, FHKAM (Paediatrics), FHKCPaed1

1 Department of Paediatrics, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong

2 Department of Chemical Pathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CH Ko (koch@ha.org.hk)

Case report

A 17-year-old Chinese male was referred to

Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong, in July 2015

for suspected migraine. His parents recalled onset

of symptoms at age 11 years, at which time the

child might suddenly hold onto rails for prolonged

rest while climbing stairs, complaining of marked

dizziness. The child sought no medical advice until

age 17 years, when symptoms worsened to almost

daily attacks. Each episode lasted from >10 minutes

to a few hours and was usually precipitated by exercise

or stress, but not by change in head position, neck

movement, or fasting. During attacks, he could not

walk along a straight line and experienced subjective

generalised weakness. School biannual 9-minute

run stamina assessment was prematurely aborted

due to incapacitating dizziness. The dizziness

was vertigo-like in nature and could be associated

with bilateral temporal headache and nausea. He

reported no tinnitus or dysarthria during attacks.

No abnormal eye movement was observed by his

parents during attacks. There was no history of aura,

photophobia, chest pain, palpitation, numbness,

visual impairment, hearing loss, tinnitus, or

syncope. He functioned normally between attacks.

Family history was negative for recurrent dizziness,

migraine headache, or neurological disease.

Neurological examination results were normal; there

was no gaze-evoked nystagmus, cerebellar signs, or

wide-based gait. Results of systemic examinations

and laboratory tests, including complete blood

picture, electrolytes, and thyroid function, were

unremarkable. Electrocardiogram and computed

tomography of the brain showed no abnormalities.

The patient was initially diagnosed with

migraine variant but experienced no improvement

after a 4-week trial of pizotifen prophylaxis. The

predominantly exercise-induced prolonged vertigo

spells, together with a relative paucity of pulsating

lateralised headaches and lack of response to migraine

treatment prompted the suspicion of episodic ataxia

type 2 (EA2). Acetazolamide was started and the

patient reported rapid clinical improvement with

>50% reduction in frequency and severity of attacks.

The patient was asked to temporarily withhold the medication; symptoms returned instantly but

responded to resumption of acetazolamide. Genetic

testing revealed a novel heterozygous variant

NM_001127222.1 (CACNA1A): c.5067+1 G>A and

was likely to be pathogenic for EA2. This mutation

was not found in the targeted genetic analyses of

the parents and is likely de novo. During follow-up

examinations, the patient reported that he could

complete school 9-minute runs.

Discussion

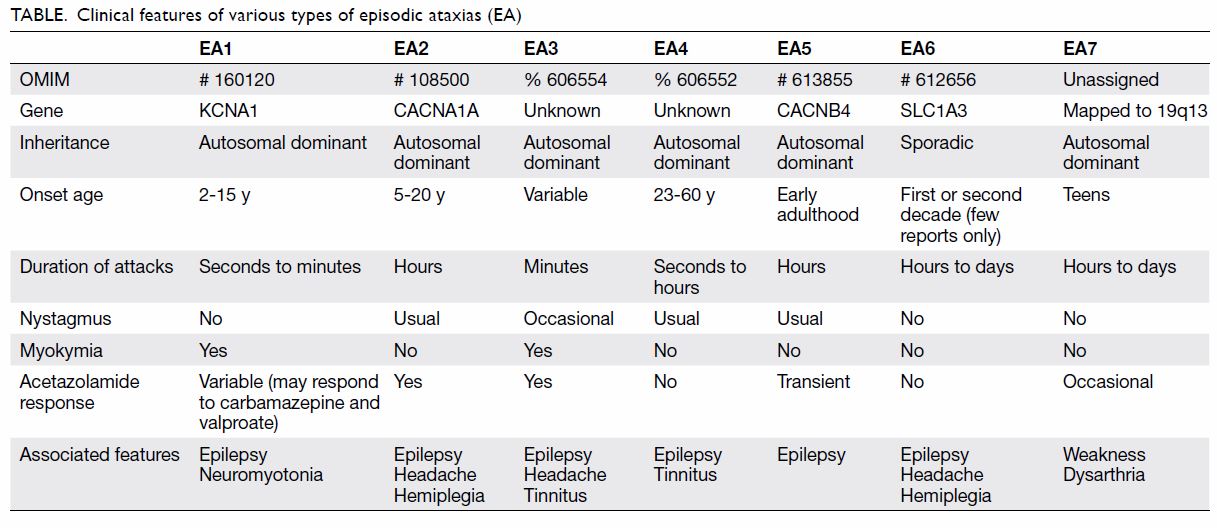

The most common type of episodic ataxia is EA2

(Table), with an estimated prevalence of <1 in

100 000.1 2 In EA2, the characteristic ataxic spells

can last from >10 minutes to hours. Triggers

include physical exertion, emotional stress,

alcohol, and caffeine. Disease onset is generally

between age 5 and 20 years. Patients are usually

symptom-free between attacks, but there may be

interictal nystagmus and gradual development of

a progressive ataxia syndrome.1 Episodic ataxia

type 2 is caused by mutations in the P/Q-type

voltage-gated calcium channel gene CACNA1A. It

encodes the pore-forming subunit of the P/Q-type

voltage-gated calcium channel, widely expressed

throughout the central nervous system, particularly

on presynaptic terminals of cerebellar Purkinje cells

and granule layer neurones. It plays a key role in

synaptic transmission. More than 80 EA2-associated

mutations on CACNA1A have been reported.1 3

Clinical diagnosis of EA2 is challenging; the

symptoms are often interpreted by primary care

physicians as being due to more common conditions

such as migraine, epilepsy, and vestibular disorders.

Overlapping features with allelic conditions of

familial alternating hemiplegia and spinocerebellar

type 6 may result in phenotype variability

including dysarthria, diplopia, tinnitus, hemiplegia

and headache.1 3 Headache may appear without

accompanying symptoms. The periodic appearance

of ostensibly functional symptoms is often

misinterpreted as migrainous; notably, 50% of EA2

cases fulfil the International Headache Society criteria

for migraine.3 In our patient, differentiating clues

included identification of prolonged ataxic spells, exercise-induced attacks, and a lack of response to

conventional migraine medications. Interictal ataxia

and nystagmus, if present, may also help differentiate

EA2 from migraine. The absence of positional

dizziness and hearing loss helps differentiate EA2

from vestibular disorders.1 Electroencephalogram

monitoring during attacks may help exclude

epilepsy. As illustrated by our patient, dramatic

improvement with acetazolamide may be diagnostic

in doubtful cases. Notwithstanding the therapeutic

response, paroxysmal exercise-induced movement

disorders with acetazolamide responsiveness may

also occur in glucose transporter defects such as

GLUT1 deficiency. It is a rare metabolic defect of

glucose uptake at the blood-brain barrier that may

present as periodic movement disorder. The latter

may have associated features of developmental delay,

microcephaly, and carbohydrate responsiveness that

are not present in EA2. The laboratory hallmark

of GLUT1 deficiency is a low cerebrospinal fluid/blood glucose ratio <0.4.4 Episodic ataxia type 2

is differentiated from other hereditary episodic

ataxias by the age of onset, spell duration, interictal

nystagmus, and genetic locus (Table).1 2 4

Therapeutically, EA2 has a dramatic response to

acetazolamide, with 50% to 75% of patients reporting

improvement in episode severity and frequency at

doses from 250 to 1000 mg daily.1 Dose escalation

is often limited by side-effects of paraesthesia,

nephrocalcinosis, fatigability and hyperhidrosis.1 5 If

acetazolamide is not tolerated, the potassium channel

blocker 4-aminopyridine may improve symptoms.

The mechanism is not fully understood; in animal

models it has been shown to prolong the action

potentials and restore the diminished precision of

pacemaking in Purkinje cells.5

In summary, EA2 is a rare neurological

disorder that can be misdiagnosed as migraine,

epilepsy, or vestibular disorders, particularly in young children who cannot give a detailed history.

Heightened physician awareness and early treatment

can significantly improve patient quality of life.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient consented to publication

of this article in a peer-reviewed journal.

References

1. Guterman EL, Yurgionas B, Nelson AB. Pearls & Oy-sters:

Episodic ataxia type 2 case report and review of the

literature. Neurology 2016;86:239-41. Crossref

2. Jen JC, Graves TD, Hess EJ, et al. Primary episodic ataxias: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Brain

2007;130:2484-93. Crossref

3. Spillane J, Kullmann DM, Hanna MG. Genetic neurological

channelopathies: molecular genetics and clinical

phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:37-48.

4. Kipfer S, Strupp M. The clinical spectrum of autosomal-dominant

episodic ataxias. Mov Disord Clin Pract

2014;1:285-90. Crossref

5. Kalla R, Teufel J, Feil K, Muth C, Strupp M. Update on the pharmacotherapy of cerebellar and central vestibular

disorders. J Neurol 2016;263 Suppl 1:S24-9. Crossref