Herpes zoster radiculopathy as a rare cause of foot drop: a case report

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Herpes zoster radiculopathy as a rare cause of

foot drop: a case report

Gene Leung, MB, ChB, MRCSEd

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Gene Leung (geneleung@gmail.com)

Case report

A 69-year-old woman with a medical history of

hypertension and hyperlipidaemia presented to

the Medicine and Geriatrics unit of Pamela Youde

Nethersole Eastern Hospital with acute onset of

right leg rash for 5 days. The rash was associated with

burning pain and dysesthesia along the right leg.

There was no back pain and no history of back injury.

She was initially diagnosed with a herpes zoster

infection and treated with a course of acyclovir and

amitriptyline and then discharged home. The patient

presented again 10 days later for new-onset right big

toe weakness with right foot drop. On the second

admission, an orthopaedic consultation was sought.

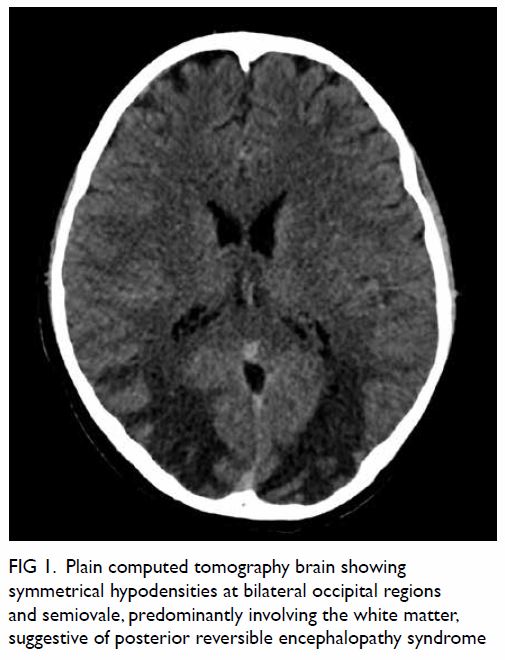

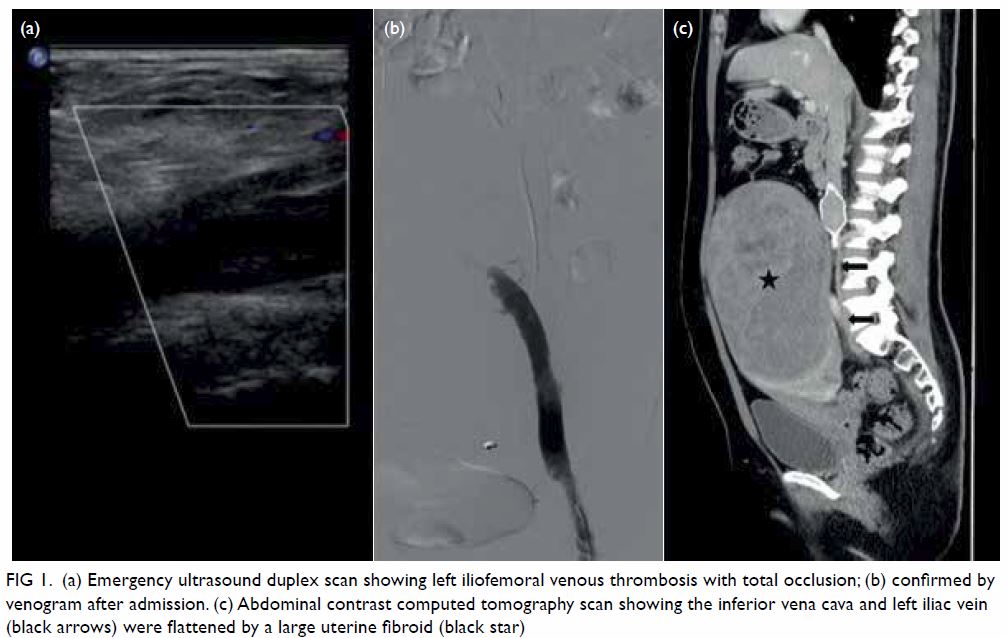

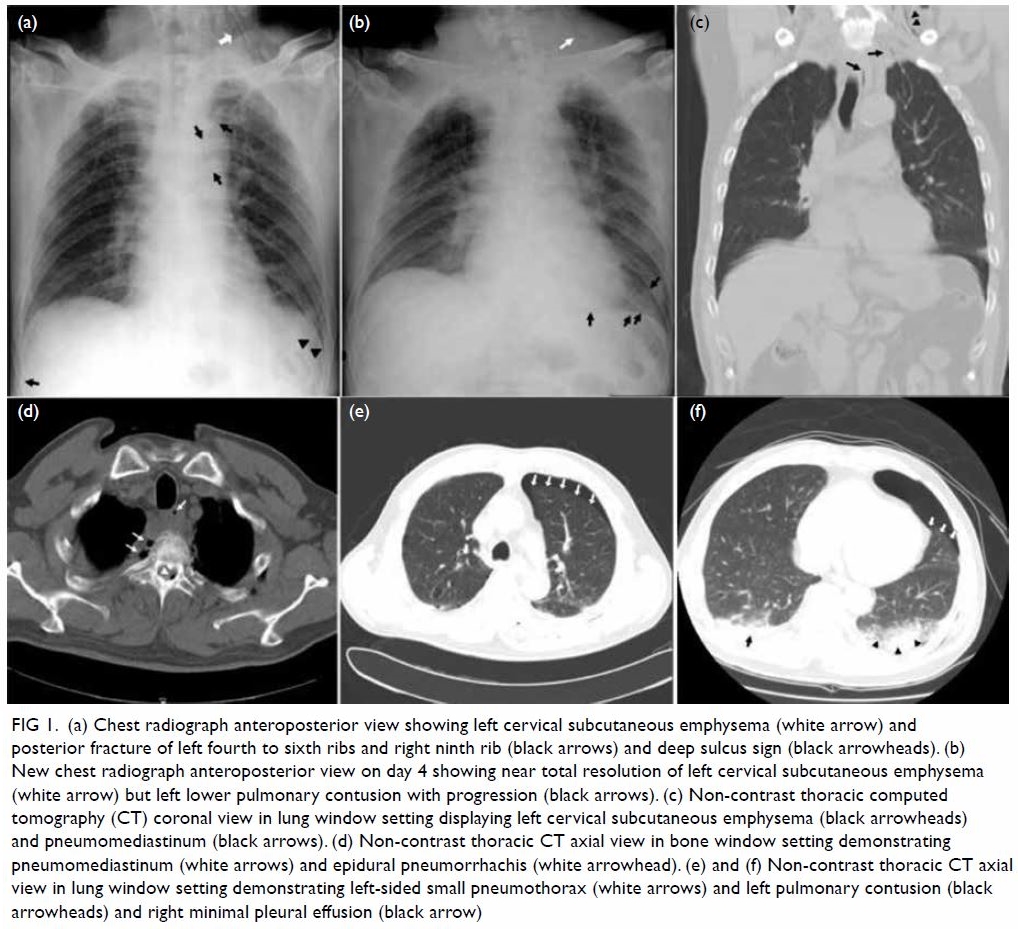

Physical examination revealed a cutaneous

papulovesicular rash and vesicles along the lateral

aspect of her right leg down to the dorsum of her

right foot (Fig 1). The rash corresponded to an L5

dermatomal distribution. Testing of sensation

showed hyperesthesia along the same region.

Right hip abduction (gluteus medius) power was

Medical Research Council (MRC) grade 4. Right

hip flexion (iliopsoas), right hip extension (gluteus

maximus), right knee flexion (hamstrings), right

knee extension (quadriceps) and right ankle plantar

flexion (gastrocnemius) demonstrated full power

of MRC grade 5. She had right foot drop with right

ankle dorsiflexion (tibialis anterior tendon), MRC

grade 2. Right big toe dorsiflexion (extensor hallucis

longus) showed a power of MRC grade 1. Right big

toe plantar flexion (flexor hallucis longus) tested

MRC grade 4 power. Right ankle inversion (tibialis

posterior) and right ankle eversion (peronei) elicited

MRC grade 3 power. Lasègue’s sign was positive for

the right lower limb but there was no tenderness

along the spine. There were no neurological deficits

of her left lower limb. Achilles tendon and patellar

tendon reflexes were normal, and sphincter function

was not disturbed.

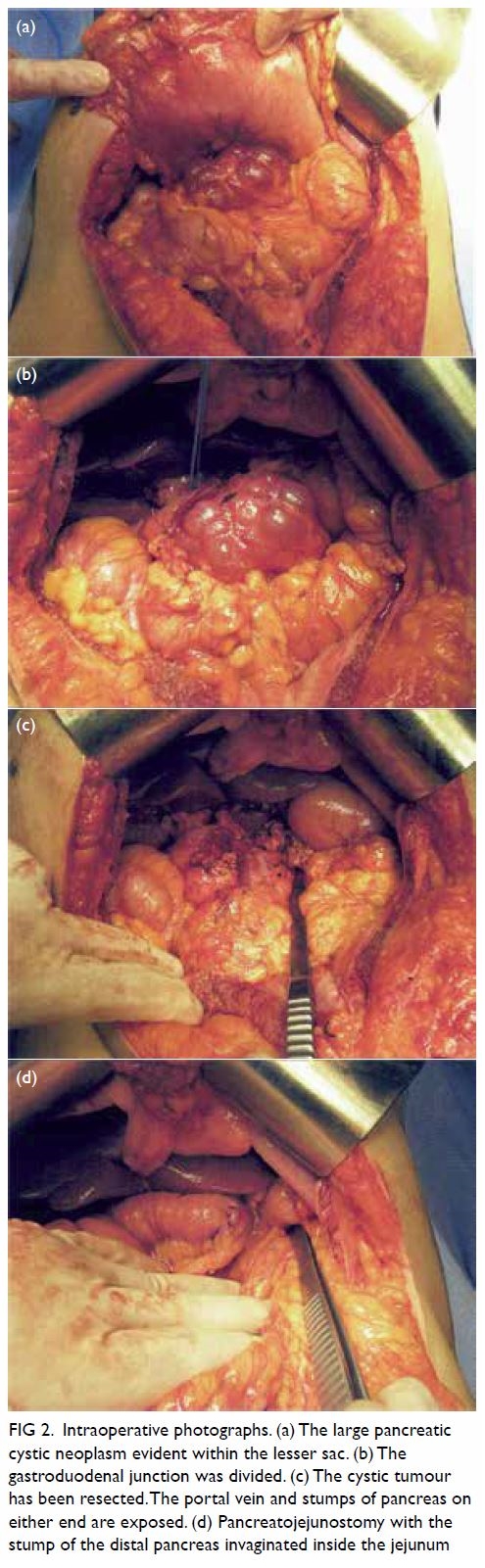

Figure 1. A 69-year-old woman with acute-onset right leg rash for 5 days, initially diagnosed as herpes zoster infection. The patient presented to the hospital again 10 days later with right foot drop. Clinical photographs of the right leg on the second admission showing a vesicular rash with right L5 dermatomal distribution

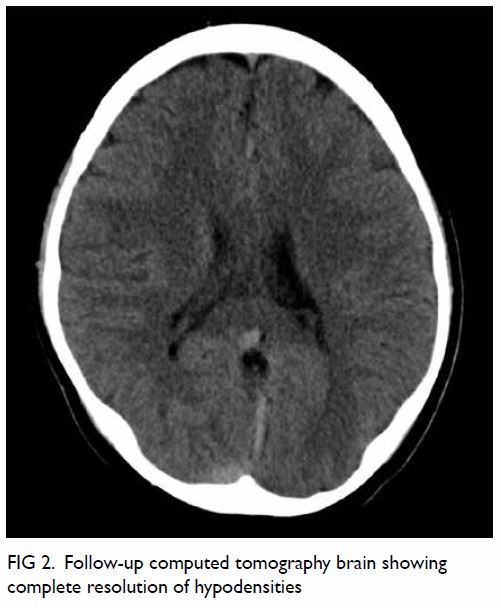

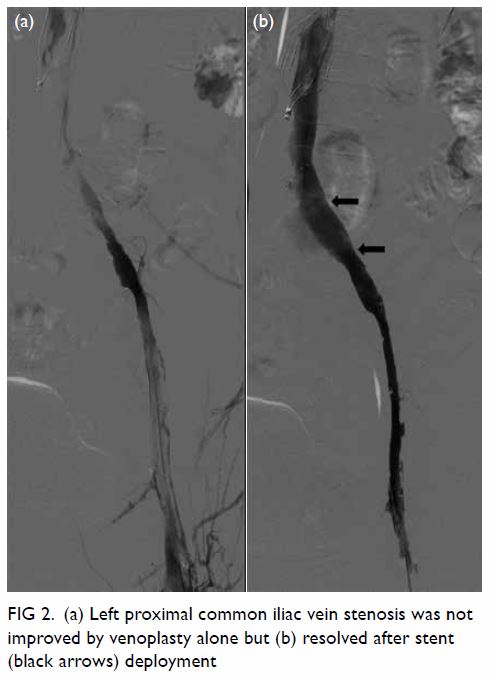

Plain radiographs of the lumbosacral spine

showed mild degeneration over the lower lumbar

facet joints. The pedicles and endplates were intact

with no vertebral collapse or slippage. The patient

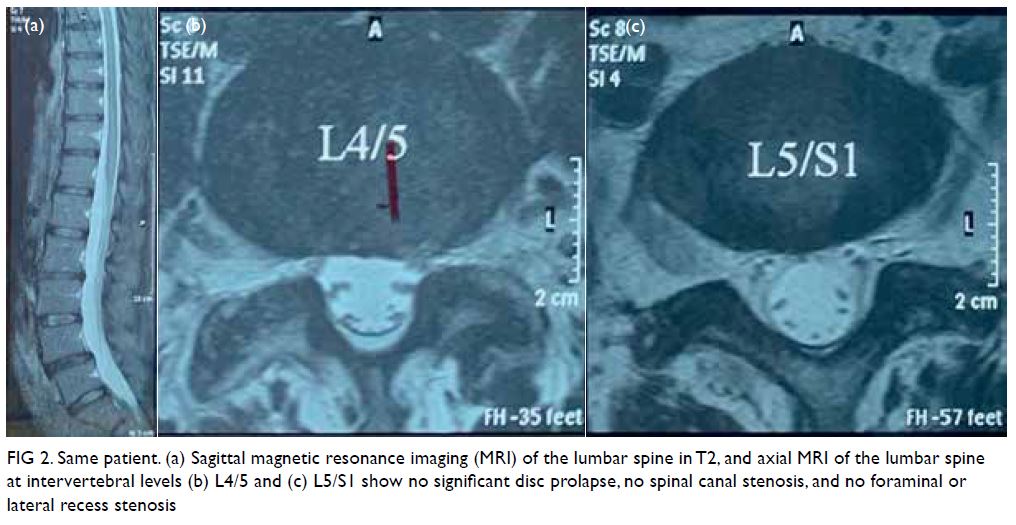

was referred for magnetic resonance imaging of

the lumbosacral spine to exclude concomitant

compression of the neurological elements (Fig 2). There was no intervertebral disc prolapse or nerve root impingement and lateral recess and

intervertebral foramen were not stenotic.

Figure 2. Same patient. (a) Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine in T2, and axial MRI of the lumbar spine at intervertebral levels (b) L4/5 and (c) L5/S1 show no significant disc prolapse, no spinal canal stenosis, and no foraminal or lateral recess stenosis

Pain medication was stepped up to gabapentin.

She was discharged with a course of out-patient

physiotherapy.

At 6-week follow-up examination, the vesicles

had crusted, and the neuropathic pain had subsided.

The power of right sided hip abduction, big toe plantar flexion, ankle plantarflexion, ankle inversion

and ankle eversion now returned to full. There was

residual weakness in right ankle dorsiflexion, with a

power of MRC grade 4, and right big toe dorsiflexion,

with a power of MRC grade 2.

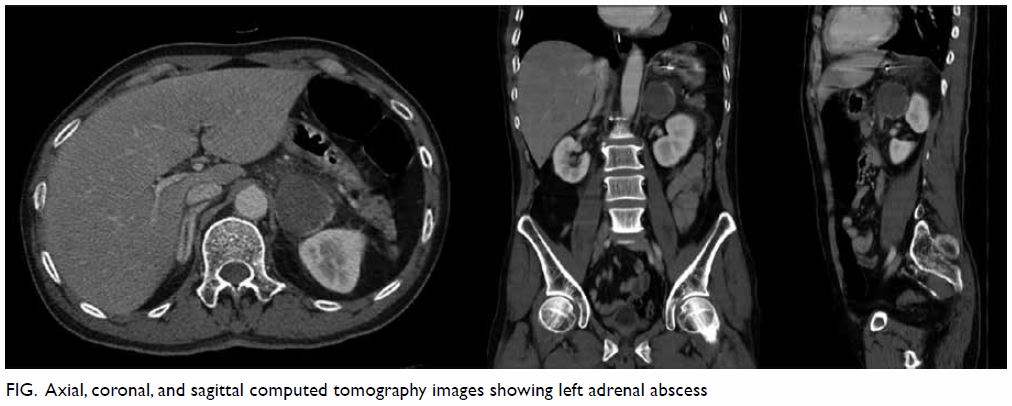

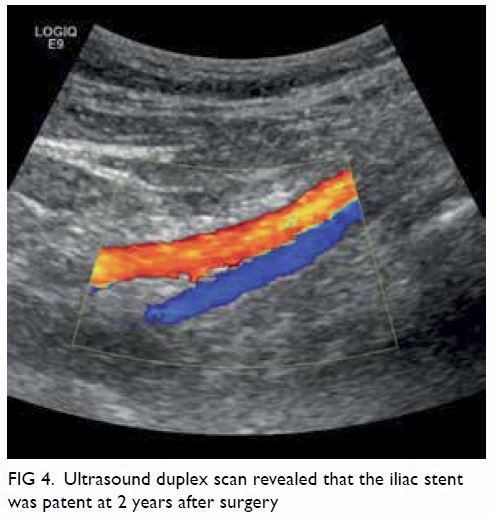

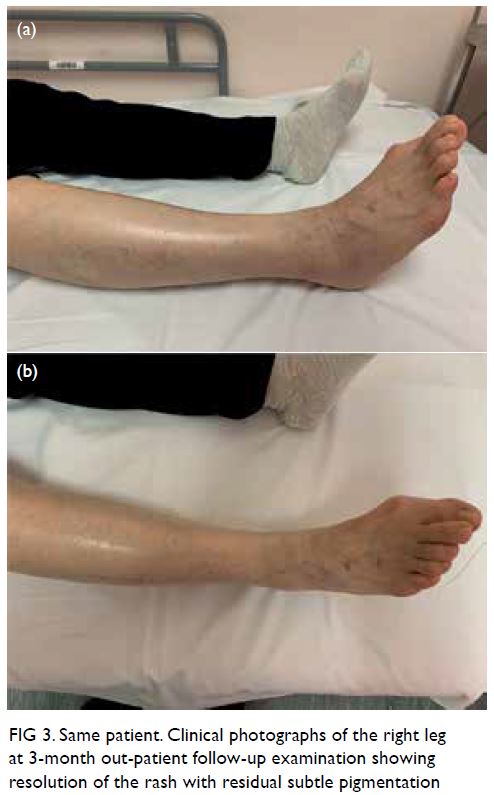

At 3-month follow-up examination, the rashes

over the right leg and foot had disappeared, leaving

faint pigmentation (Fig 3). She was pain free. Right

ankle dorsiflexion power was full and right big toe

dorsiflexion power further improved to MRC grade 3.

She was weaned off gabapentin and continued with

physiotherapy for ankle strengthening exercises.

Figure 3. Same patient. Clinical photographs of the right leg at 3-month out-patient follow-up examination showing resolution of the rash with residual subtle pigmentation

Discussion

Herpes zoster is a viral infection of the nervous

system that results from the reactivation of a

previous varicella zoster virus infection, often in

childhood. The virus lays dormant in the dorsal

root ganglion re-emerging as the patient ages or

becomes immunocompromised.1 It manifests with

a typical cutaneous vesicular rash that follows a

spinal nerve distribution. Classically, it is believed

that the virus spreads from the dorsal root ganglion

in an antegrade fashion along the spinal nerve.

Thus, symptoms are most often purely sensory.

Rarely, when motor manifestations are present, they

tend to affect more proximal muscle groups.2 The

typical example is Bell’s palsy due to facial nerve

involvement. It has been hypothesised that local

inflammation of the dorsal root ganglion results in

hypervascularity in the surrounding nerve tissue,

disrupting the blood-nerve barrier which can also

result in a motor deficit.3 Therefore, although post-herpetic

neuralgia is a common manifestation of

herpes zoster infection, segmental zoster paresis is rare. Although reported incidences in different

countries vary, a recent study performed with a

majority of Chinese patients reported paresis in only 0.57% of those afflicted with a zoster infection.2 Since

lumbar radiculopathy resulting from intervertebral

disc herniation with nerve root irrigation commonly

involves L4/5 and L5/S1 levels, a herpes zoster

infection with segmental paresis affecting the L5

spinal nerve is a close mimicker. In some instances,

the motor weakness can precede the rash.4

The diagnosis of herpes zoster radiculopathy is

clinical although it can be aided by serum antibodies,

electrodiagnostic studies and formal dermatological

assessment. For this case, although electrodiagnostic

testing would have been ideal to supplement the

overall assessment, it was not arranged due to the

anticipated recovery and resource limitations in

the public hospital setting. As the lumbar spinal

nerve roots were involved, the clinical presentation

resembled compressive pathologies that are

commonly seen in orthopaedics. A plain magnetic

resonance imaging can exclude the presence of

nerve root impingement, although findings that may

suggest zoster infection such as spinal nerve swelling

with T2 hyperintensity are neither sensitive nor

specific.3

The mainstay of treatment for zoster

radiculopathy is pharmacological. A course of

antivirals is prescribed for the acute herpetic

infection. Pain is managed according to the World

Health Organization analgesic ladder or with specific

neuropathic pain medication such as amitriptyline,

gabapentin or pregabalin. Although the clinical

course is variable, most patients can expect to make

a near-complete motor recovery within 1 year.2 A

well-fitted ankle-foot orthosis facilitates ambulation

if there is persistent foot drop. In addition,

transforaminal epidural steroid injections have been

reported to mitigate pain and weakness by suppressing

inflammation along the spinal root.5 However, the use of corticosteroids remains controversial as there

is a theoretical risk of viral reactivation.3

Author contributions

The author contributed to the concept of the study, acquisition

and analysis of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical

revision for important intellectual content. The author had

full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the

final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all

procedures.

References

1. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:9-20. Crossref

2. Liu Y, Wu BY, Ma ZS, et al. A retrospective case series of segmental zoster paresis of limbs: clinical,

electrophysiological and imaging characteristics. BMC

Neurol 2018;18:121. Crossref

3. Hackenberg RK, von den Driesch A, König DP. Lower back

pain with sciatic disorder following L5 dermatome caused

by herpes zoster infection. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2015;7:6046. Crossref

4. Teo HK, Chawla M, Kaushik M. A rare complication of herpes zoster: segmental zoster paresis. Case Rep Med.

2016;2016:7827140. Crossref

5. Conliffe TD, Dholakia M, Broyer Z. Herpes zoster

radiculopathy treated with fluoroscopically-guided selective

nerve root injection. Pain Physician 2009;12:851-3. Crossref