Evaluation of contemporary olanzapine- and netupitant/palonosetron-containing antiemetic regimens for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

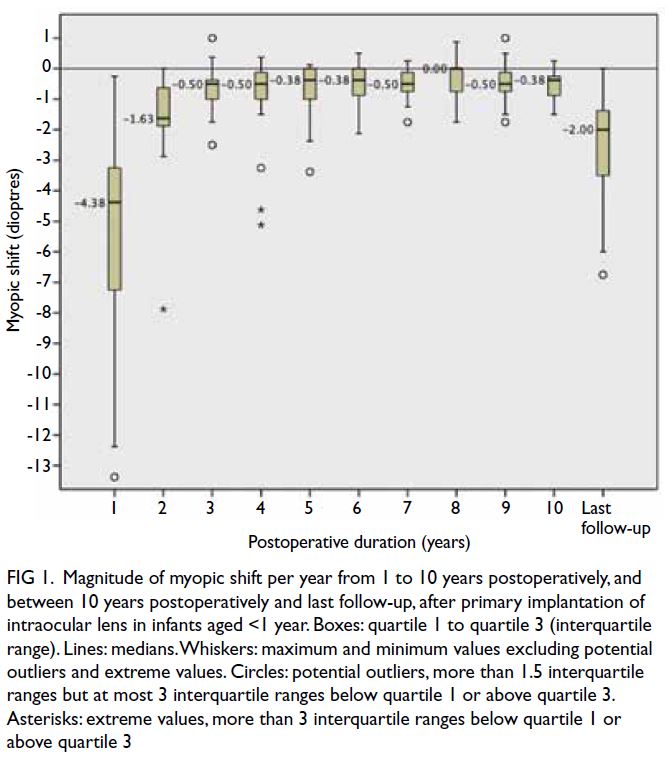

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

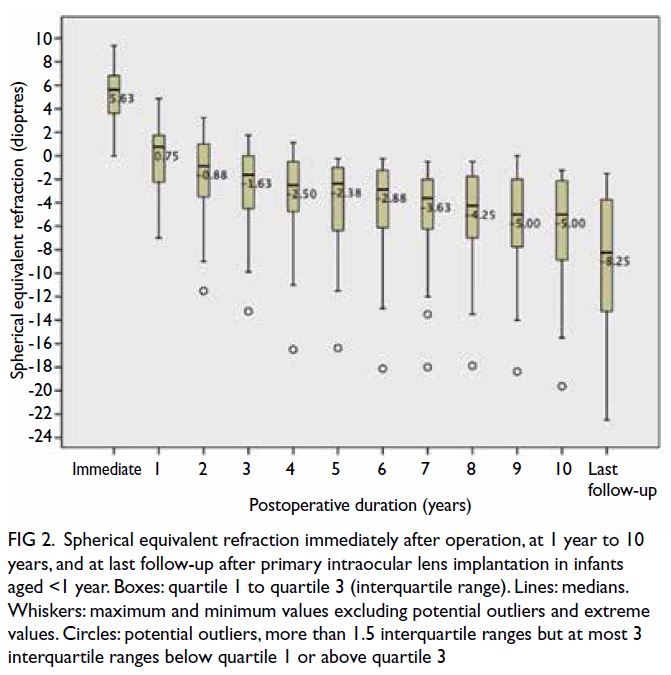

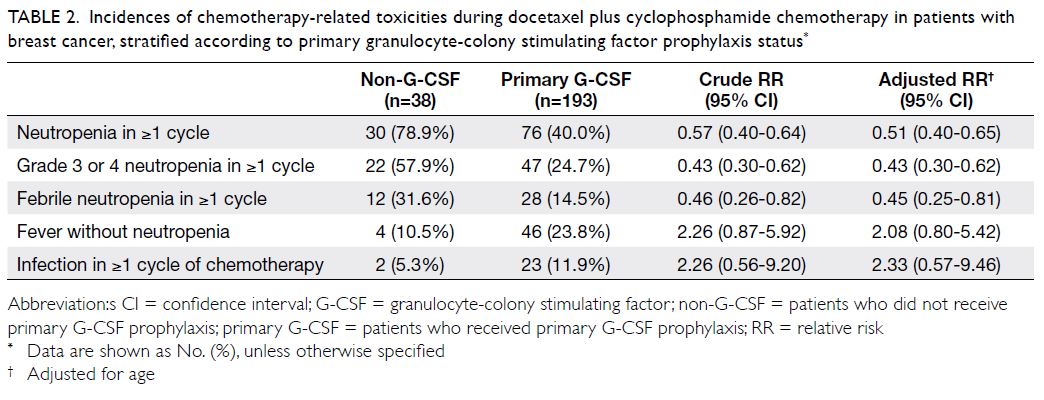

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of contemporary olanzapine- and netupitant/palonosetron-containing antiemetic regimens for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

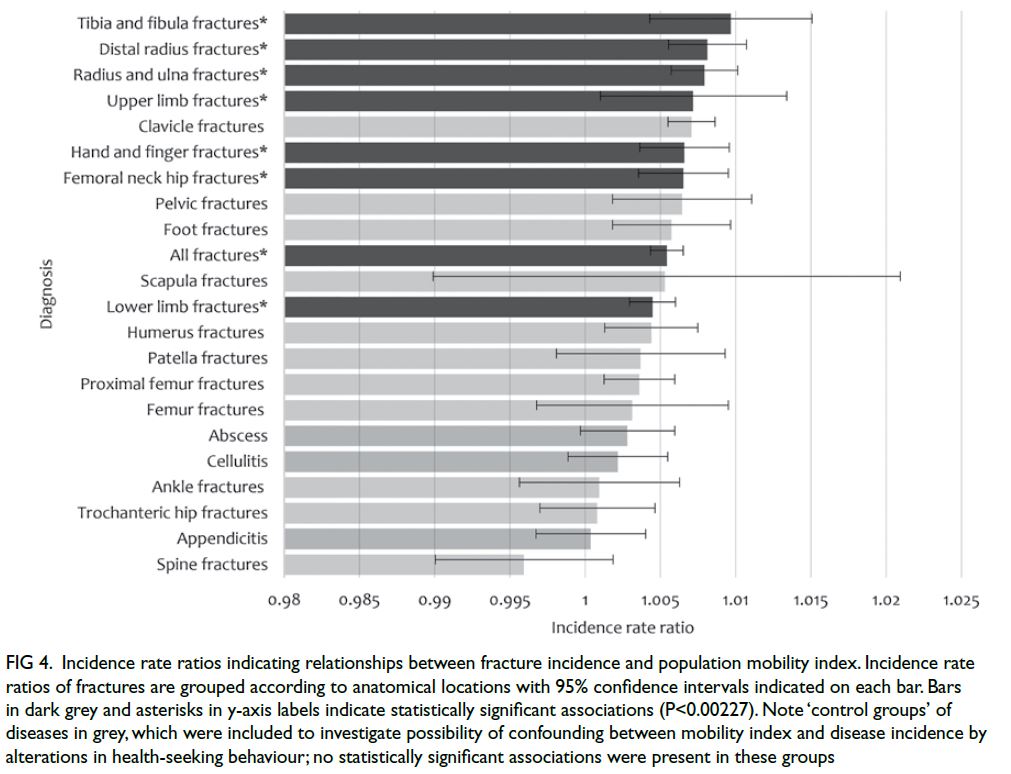

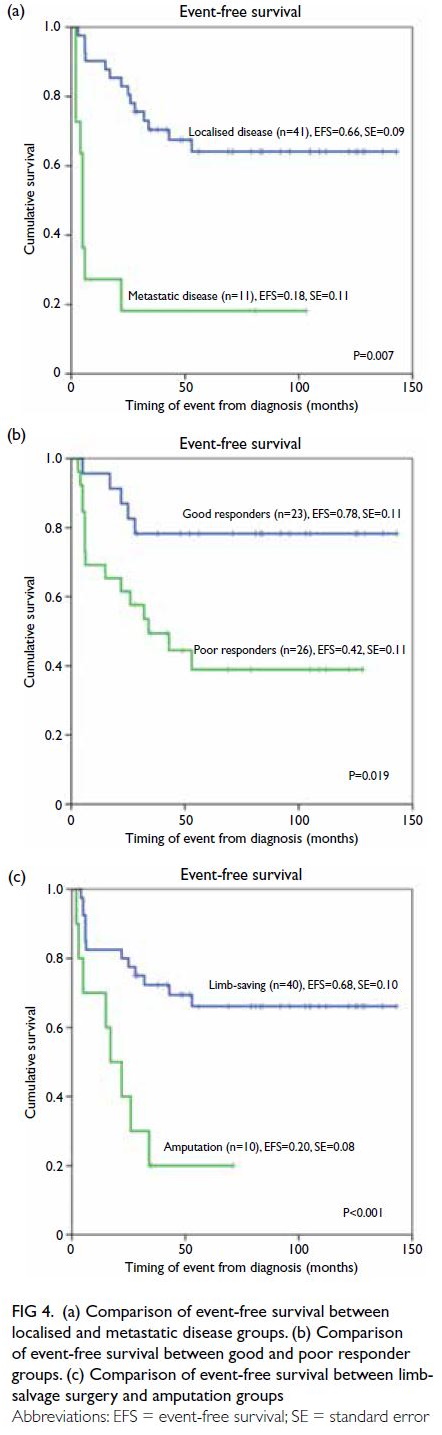

Christopher CH Yip1; L Li, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Thomas KH Lau, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Vicky TC Chan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Carol CH Kwok, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)2; Joyce JS Suen, MB, BS, FHKAM (Radiology)2; Frankie KF Mo, PhD1; Winnie Yeo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1

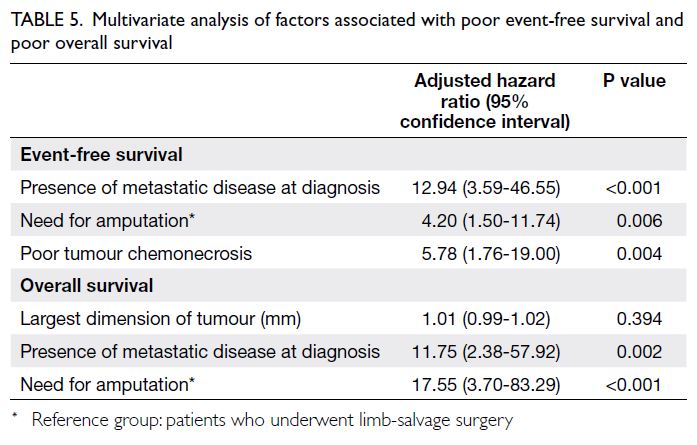

1 Department of Clinical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Clinical Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Winnie Yeo (winnieyeo@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This post-hoc analysis retrospectively

assessed data from two recent studies of antiemetic

regimens for chemotherapy-induced nausea and

vomiting (CINV). The primary objective was to

compare olanzapine-based versus netupitant/palonosetron (NEPA)-based regimens in terms of

controlling CINV during cycle 1 of doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (AC) chemotherapy; secondary

objectives were to assess quality of life (QOL) and

emesis outcomes over four cycles of AC.

Methods: This study included 120 Chinese patients

with early-stage breast cancer who were receiving

AC; 60 patients received the olanzapine-based

antiemetic regimen, whereas 60 patients received the

NEPA-based antiemetic regimen. The olanzapine-based

regimen comprised aprepitant, ondansetron,

dexamethasone, and olanzapine; the NEPA-based

regimen comprised NEPA and dexamethasone.

Patient outcomes were compared in terms of emesis

control and QOL.

Results: During cycle 1 of AC, the olanzapine group

exhibited a higher rate of ‘no use of rescue therapy’

in the acute phase (olanzapine vs NEPA: 96.7% vs

85.0%, P=0.0225). No parameters differed between

groups in the delayed phase. The olanzapine

group had significantly higher rates of ‘no use of rescue therapy’ (91.7% vs 76.7%, P=0.0244) and ‘no

significant nausea’ (91.7% vs 78.3%, P=0.0408) in

the overall phase. There were no differences in QOL

between groups. Multiple cycle assessment revealed

that the NEPA group had higher rates of total control

in the acute phase (cycles 2 and 4) and the overall

phase (cycles 3 and 4).

Conclusion: These results do not conclusively support the superiority of either regimen for patients

with breast cancer who are receiving AC.

New knowledge added by this study

- The olanzapine-based regimen (aprepitant, ondansetron, dexamethasone, and olanzapine) and the NEPA-based regimen (netupitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone) demonstrated similar efficacies in terms of controlling chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting among patients with early-stage breast cancer.

- Quality of life did not significantly differ between patients receiving the olanzapine-based regimen and patients receiving the NEPA-based regimen.

- The available data suggest that olanzapine-containing antiemetic regimens can be used without aprepitant, particularly when seeking to reduce medical expenses.

- Antiemetic efficacy may potentially be enhanced if NEPA is administered in combination with dexamethasone and olanzapine as a four-drug antiemetic regimen.

Introduction

Patients with breast cancer receiving (neo)adjuvant treatment exhibit improved prognoses.1 However,

chemotherapy regimens for breast cancer are

associated with various degrees of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). The

doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (AC) regimen is

one of the most frequently prescribed regimens for

patients with breast cancer who are receiving (neo)

adjuvant chemotherapy; AC is among the highly emetogenic chemotherapies with ≥90% risk of nausea and vomiting.

In situations where a neurokinin-1 receptor

antagonist (NK1RA) is accessible, most current

guidelines for AC(-like) chemotherapy recommend

the use of a prophylactic triplet antiemetic regimen

that consists of an NK1RA, a 5-hydroxytryptamine

type-3 receptor antagonist (5HT3RA), and a

corticosteroid, with or without olanzapine.2 3 4

In addition to earlier NK1RAs (eg, aprepitant,

fosaprepitant, and rolapitant), netupitant/palonosetron (NEPA) [Akynzeo], which is a

combination of an NK1RA (netupitant 100 mg) and

a second-generation 5HT3RA (palonosetron 0.5

mg), has been available in the past decade. Although

palonosetron constitutes a more potent 5HT3RA,5 it

also has synergistic interactions with netupitant that

include interference with 5HT3 receptor cross-talk

and enhancement of the netupitant-mediated effect

on NK1 receptor internalisation.6 7

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis,

Yokoe et al8 compared different antiemetic regimens to assess their control of CINV in

patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy

regimens. The authors arbitrarily defined the

‘conventional’ regimen as a three-drug regimen

that contained dexamethasone, a first- or second-generation secondgeneration

5HT3RA, and an earlier NK1RA

compound (aprepitant, fosaprepitant, or rolapitant);

they defined ‘new’ regimens as regimens that

contained NEPA or olanzapine. The results indicated

that, compared with conventional regimens, new

regimens containing NEPA were more effective

in terms of producing a complete response (ie,

absence of vomiting and no use of rescue therapy).

Additionally, Yokoe et al8 showed that olanzapine-containing

regimens were most effective in terms

of producing a complete response, particularly

when olanzapine was added to a triplet regimen

of an NK1RA, a 5HT3RA, and dexamethasone.

These findings were supported by the results of a

prospective randomised study published in 2020,

which directly compared an olanzapine-containing

four-drug regimen with a standard triplet antiemetic

regimen (consisting of aprepitant, ondansetron,

and dexamethasone) for the prevention of CINV in

patients receiving AC chemotherapy.9

Here, we conducted a post-hoc analysis through

retrospective assessment of individual patient

data from two previously reported prospective

antiemetic studies that involved Chinese patients

with breast cancer.9 10 We hypothesised that a four-drug

antiemetic regimen (consisting of an NK1RA,

a 5HT3RA, dexamethasone, and olanzapine) would

remain superior to a three-drug regimen (consisting

of an NK1RA, a 5HT3RA, and dexamethasone)

that included NEPA as a combination NK1RA

and 5HT3RA agent. The primary objective was

to compare the efficacies of olanzapine- and

NEPA-containing antiemetic regimens in terms of

controlling CINV during the first cycle of AC. The

secondary objectives were: (1) to assess quality of

life (QOL) outcomes in patients receiving these

treatments during the first cycle of AC, and (2) to

assess emesis control outcomes in patients receiving

these treatments over multiple cycles of AC.

Methods

Patients

This study constituted a post-hoc analysis of data from two recently reported prospective studies. The

first prospective study investigated emesis outcomes

in patients with breast cancer who received a

standard triplet antiemetic regimen (ie, aprepitant,

ondansetron, and dexamethasone) with or without

olanzapine9; after the first study, a second prospective

study was conducted to assess the antiemetic efficacy

of NEPA and dexamethasone.10 These studies were

conducted with institutional ethics approval and

were registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03386617

and NCT03079219, respectively). For the post-hoc

analysis, data were extracted from the first study

regarding patients who received an olanzapine plus

aprepitant-containing four-drug antiemetic regimen; data were extracted from the second study regarding

patients who received NEPA and dexamethasone.

These patients were categorised into the ‘olanzapine’

and ‘NEPA’ groups, respectively.

Inclusion criteria were similar for the two

studies. Specifically, patients were eligible if they were

women of Chinese ethnicity, were aged >18 years,

had early-stage breast cancer, and planned to

receive a regimen of (neo)adjuvant AC. All study

participants were required to read, understand,

and complete study questionnaires and diaries

in Chinese. Exclusion criteria included abnormal

bone marrow, renal, or hepatic functions; receipt or

planned receipt of radiation therapy to the abdomen

or pelvis within 7 days prior to initial administration

of study treatment; presence of grade 2 to 3 nausea,

as defined by the National Cancer Institute Common

Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version

4.0,11 or vomiting within 24 hours prior to initial

administration of the study treatment; presence of

an active infection or any uncontrolled disease; a

history of illicit drugs, including marijuana or alcohol

abuse; mental incapacitation; and/or presence of

a clinically significant emotional or psychiatric

disorder. Written consent was provided by eligible

patients prior to enrolment in the studies.

Study treatment

Patients in the olanzapine group received olanzapine 10 mg, aprepitant 125 mg, dexamethasone 12 mg,

and ondansetron 8 mg before chemotherapy on

day 1; they also received ondansetron 8 mg 8 hours

after chemotherapy. Subsequently, they received

aprepitant 80 mg daily on days 2-3 and olanzapine

10 mg daily on days 2-5.

Patients in the NEPA group received one

capsule of NEPA (netupitant 300 mg/palonosetron

0.50 mg) with dexamethasone 12 mg before

chemotherapy on day 1. Subsequently, they received

dexamethasone 4 mg twice per day on days 2-3.

Study assessments

At the initiation of chemotherapy on day 1, individual

patients were provided a diary to record the date and

time of their symptoms of vomiting and nausea for

120 hours after the AC infusion; the use of any rescue

medication was also recorded. On days 2-6, patients

rated their symptoms of nausea for the previous

24 hours using a visual analogue scale (in which 0 mm

implied no nausea, whereas 100 mm implied nausea

that was ‘as bad as it could be’). Additionally, on day 1

(before infusion of AC) and day 6 (after completion of

the diary), patients completed the Functional Living

Index-Emesis (FLIE) questionnaire. A research

nurse/assistant called individual patients on days

2-6 to remind them to take the study medications,

complete the patient diary, and complete the FLIE

questionnaire.

Assessment of efficacy and safety

Antiemetic efficacy was measured across three

overlapping time periods. The ‘acute’ phase

comprised 0 to 24 hours from the infusion of AC;

the ‘delayed’ phase comprised 24 to 120 hours from

the infusion of AC; the ‘overall’ phase comprised 0 to

120 hours from the infusion of AC.

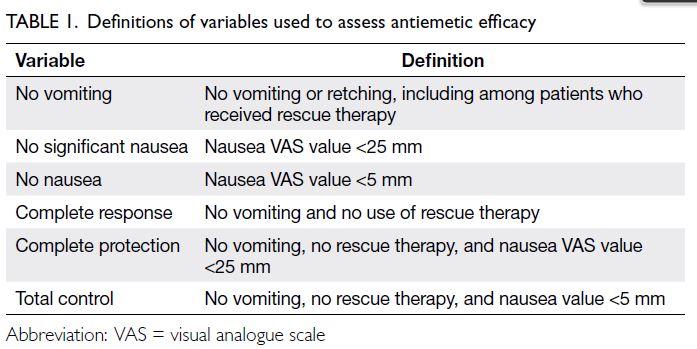

Variables used to assess antiemetic efficacy

were ‘complete response’, ‘no vomiting’, ‘no

significant nausea’, ‘no nausea’, ‘no use of rescue

therapy’, ‘complete protection’, and ‘total control’;

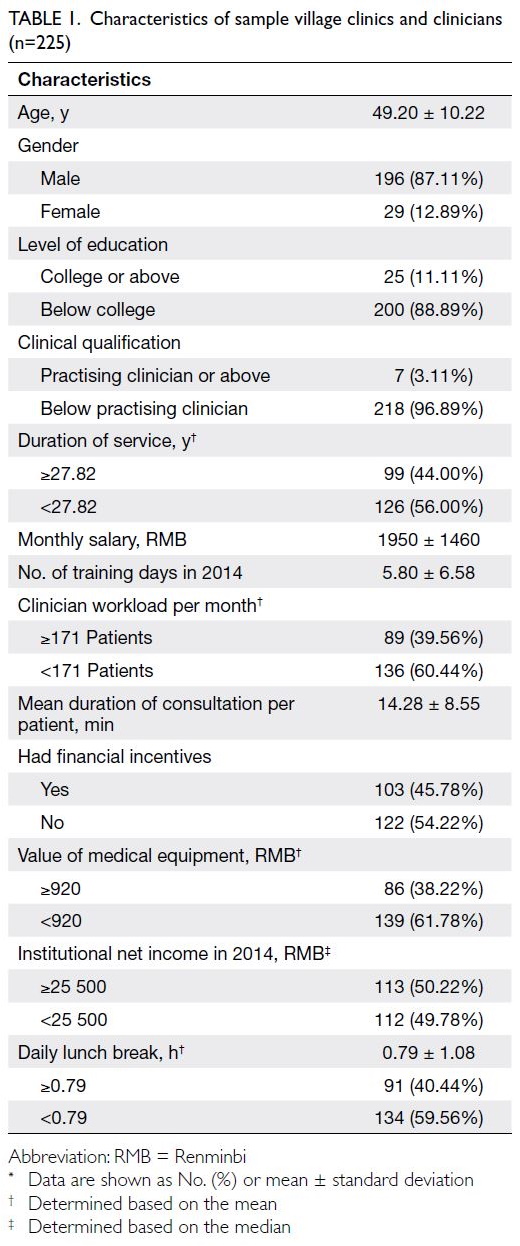

definitions of these variables are provided in Table 1. The proportions of patients who exhibited these

variables were recorded separately. Additionally, the

‘time to first vomiting’ in cycle 1 was determined

using information recorded in patients’ diaries.

Quality of life was evaluated using the Chinese

version of self-reported FLIE questionnaires from

individual patients.12 The FLIE questionnaire consists

of a nausea domain (9 items) and a vomiting domain

(9 items). All scores were transformed to ensure that

higher scores indicated worse impact on QOL.

Statistical analyses

A modified intention-to-treat approach was used

for all efficacy analyses; specifically, analyses

included patients who had received chemotherapy,

had completed the study procedures from 0 to 120

hours in cycle 1 of AC, and had no major protocol

violations.

To achieve the primary objective of this

study, the efficacies of the two antiemetic regimens

were based on the proportions (including 95%

confidence intervals) of patients who achieved

complete response during the acute, delayed, and

overall phases after AC infusion in cycle 1. Other

parameters compared in cycle 1 of AC were ‘time to

first vomiting’, ‘no vomiting’, ‘no significant nausea’,

no nausea’, ‘no use of rescue therapy’, ‘complete

protection’, and ‘total control’.

To achieve the secondary objectives, QOL was

compared between the two antiemetic regimens based on assessments of the nausea domain,

vomiting domain, and total score (sum of nausea

and vomiting domains) of the FLIE questionnaire

during cycle 1 of AC. Emesis control over multiple

cycles was compared between the two antiemetic

regimens by assessing the proportions (including

95% confidence intervals) of patients who achieved

‘complete response’, ‘complete protection’, and ‘total

control’ in the acute, delayed, and overall phases.

Comparisons between the two antiemetic

regimens were made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum

test for continuous data and Pearson’s Chi squared

test for dichotomous data. Two-sided P values <0.05

were considered statistically significant. The SAS Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary [NC], United States) was used for analyses.

Results

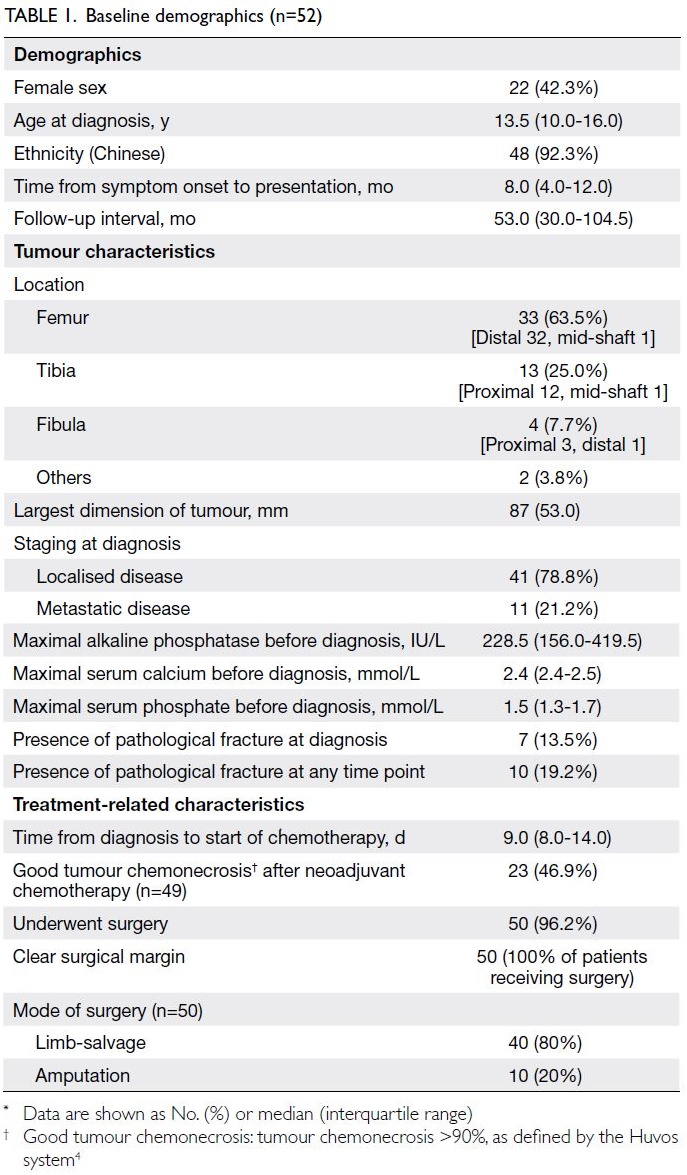

Patient characteristics

Data from 120 patients were included in this study; 60 patients each were enrolled in the NEPA and

olanzapine groups. Fifty-six patients (93.3%) in the

olanzapine group completed all four cycles of AC,

whereas 60 patients (100%) in the NEPA group

completed all four cycles of AC.

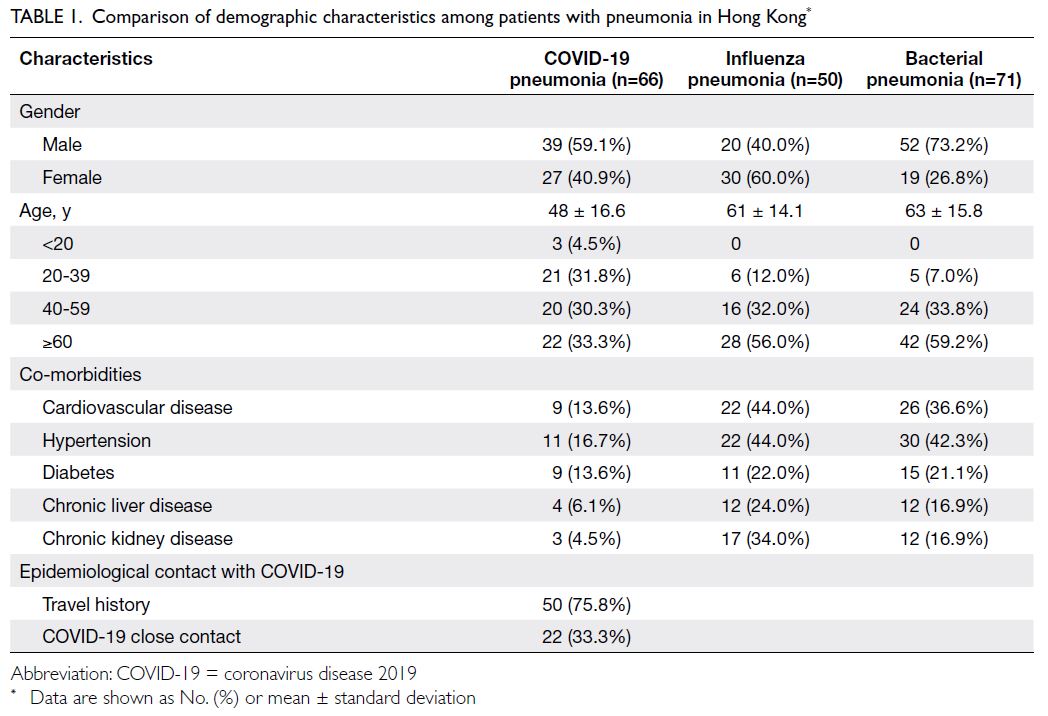

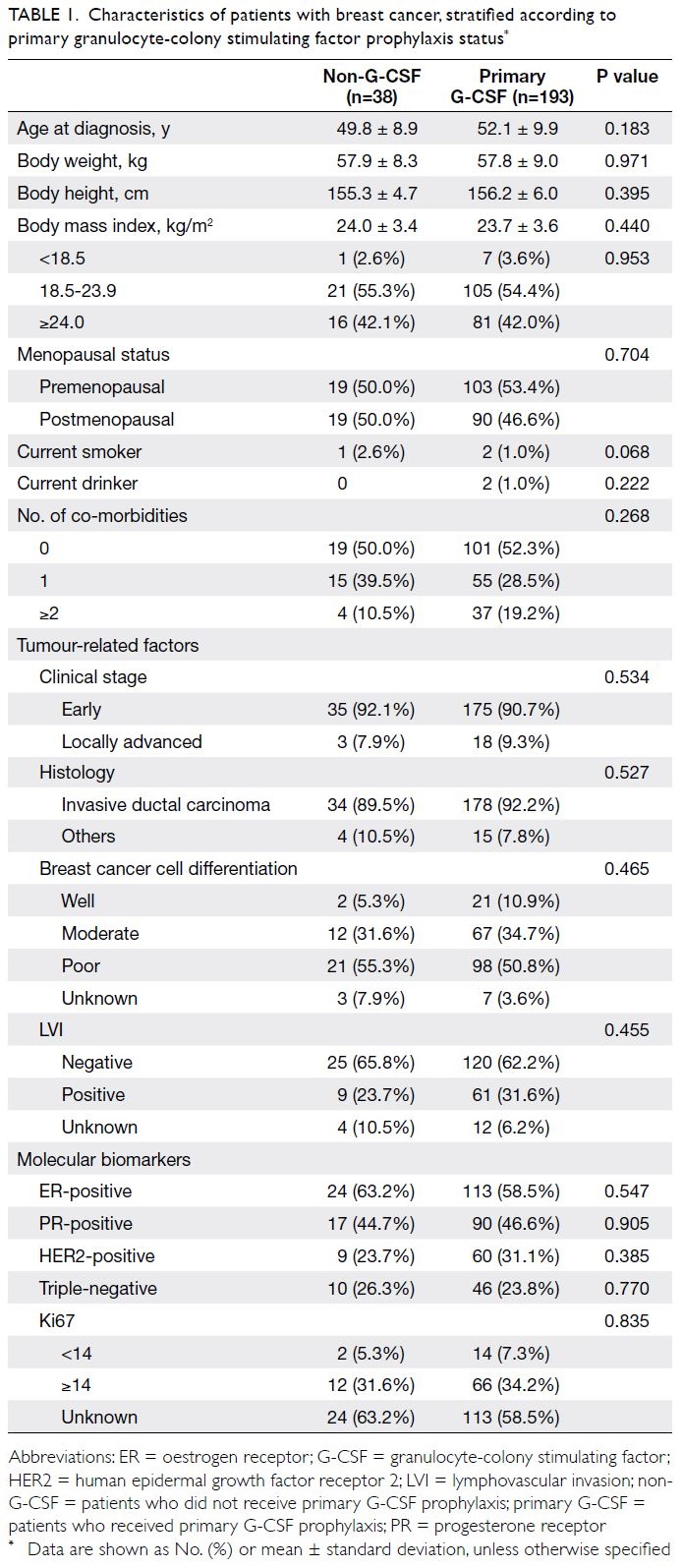

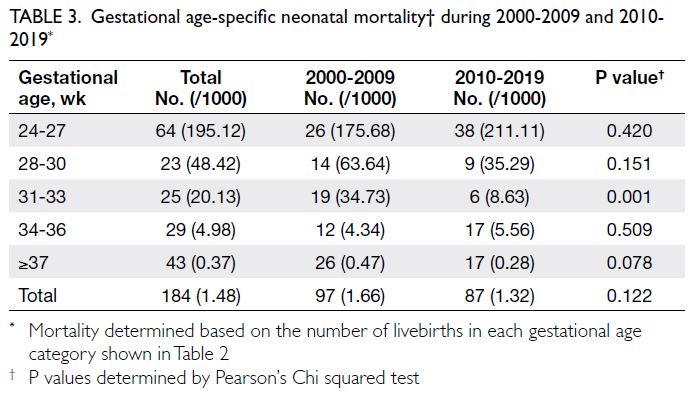

Patient characteristics, including

characteristics that could potentially affect CINV,

are shown in Table 2. The olanzapine and NEPA

groups had very similar patient characteristics, with

median ages of 54.5 and 56 years, respectively. Nearly

two-thirds of patients in each group had Stage II

breast cancer (63.3% and 66.7%, respectively). The

percentage of patients with a history of motion

sickness was higher in the NEPA group (35%) than

in the olanzapine group (16.7%). Furthermore, 30%

of patients in the NEPA group and 20% of patients

in the olanzapine group received AC as neoadjuvant

treatment.

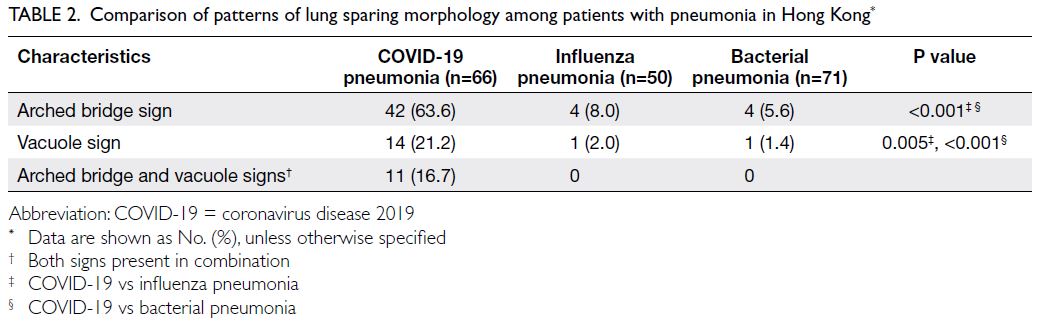

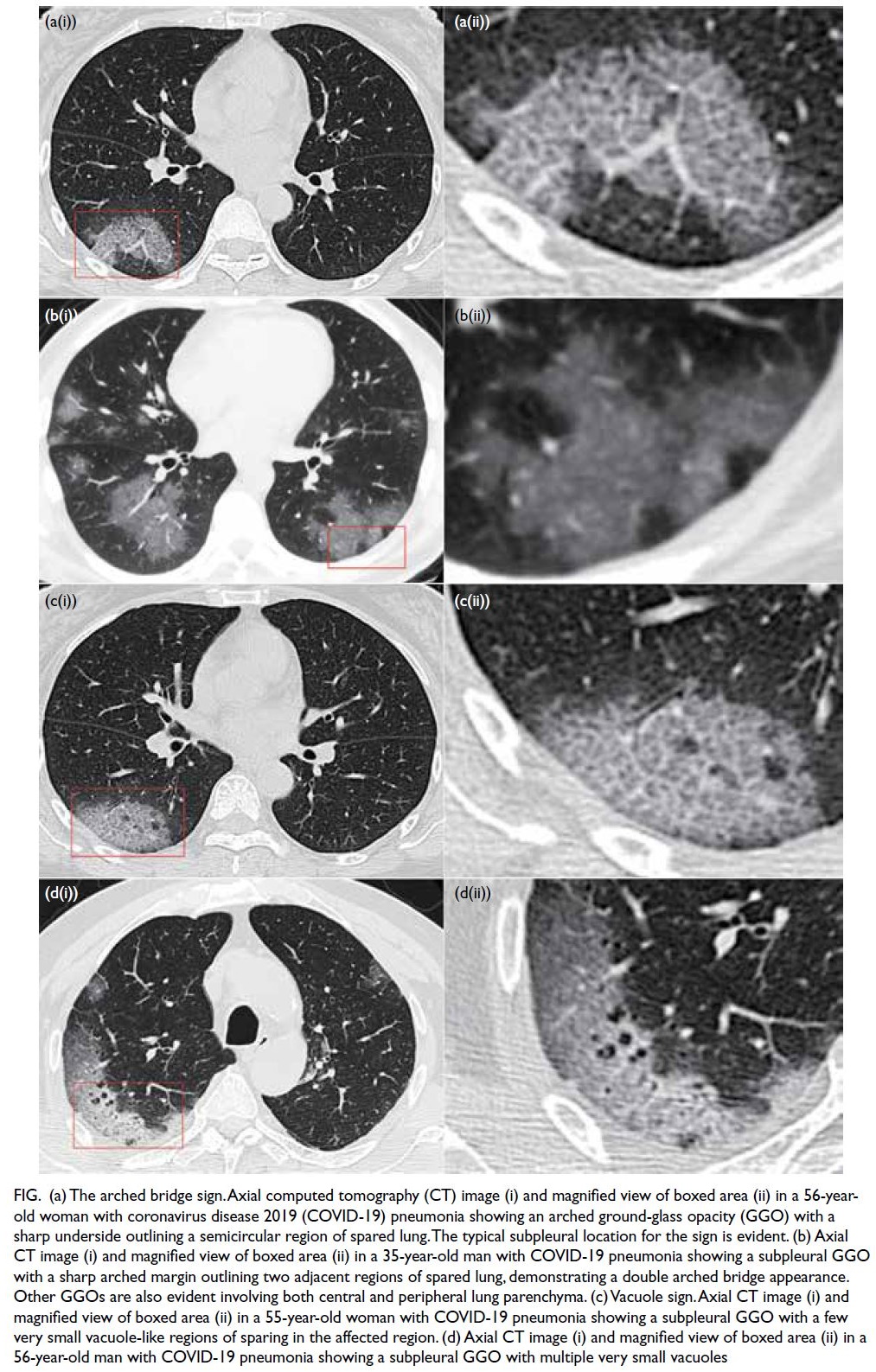

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of Chinese patients with early-stage breast cancer included in this analysis

Efficacy assessment

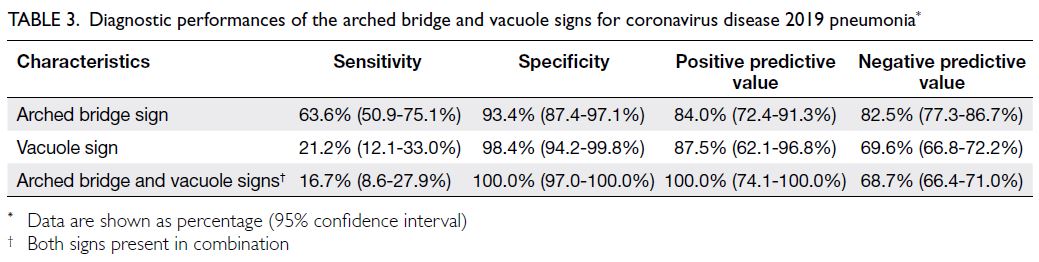

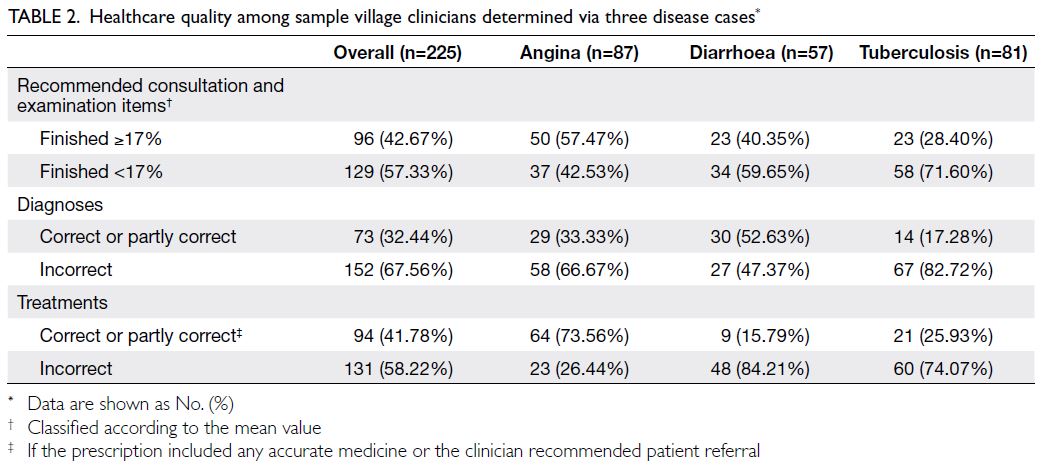

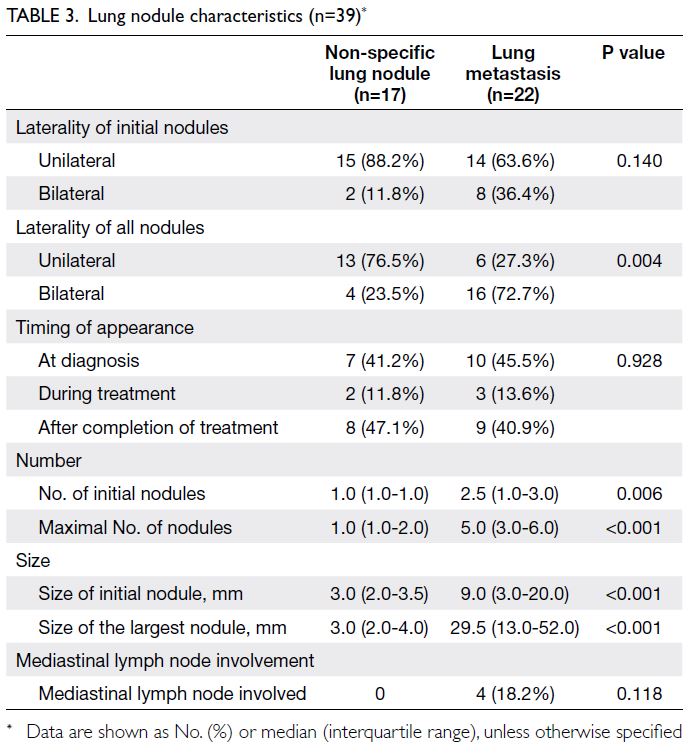

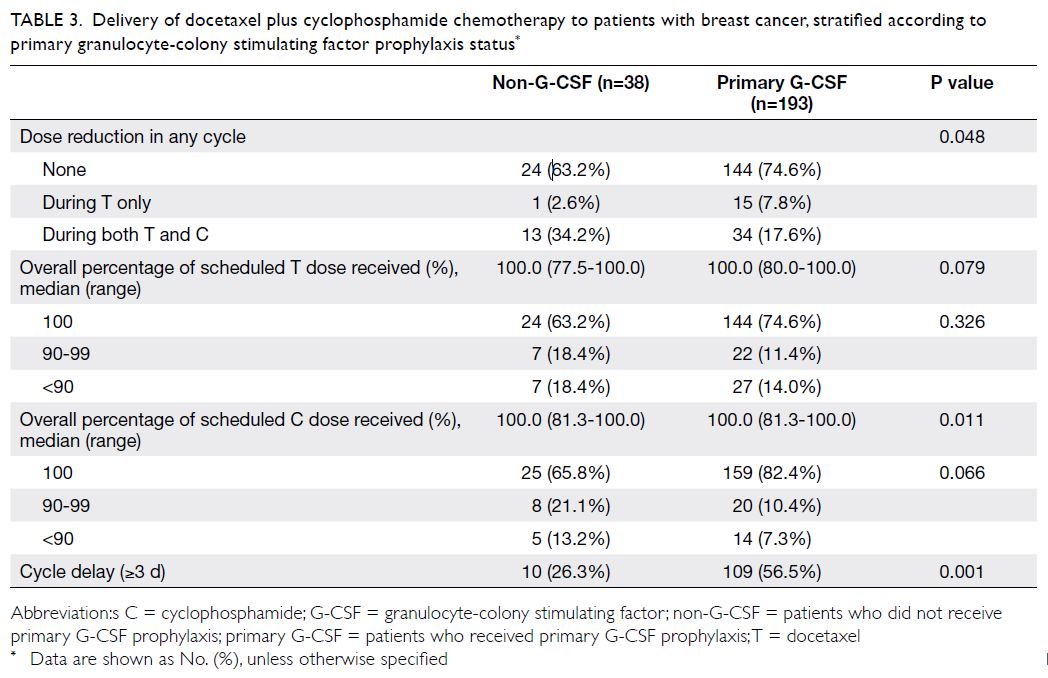

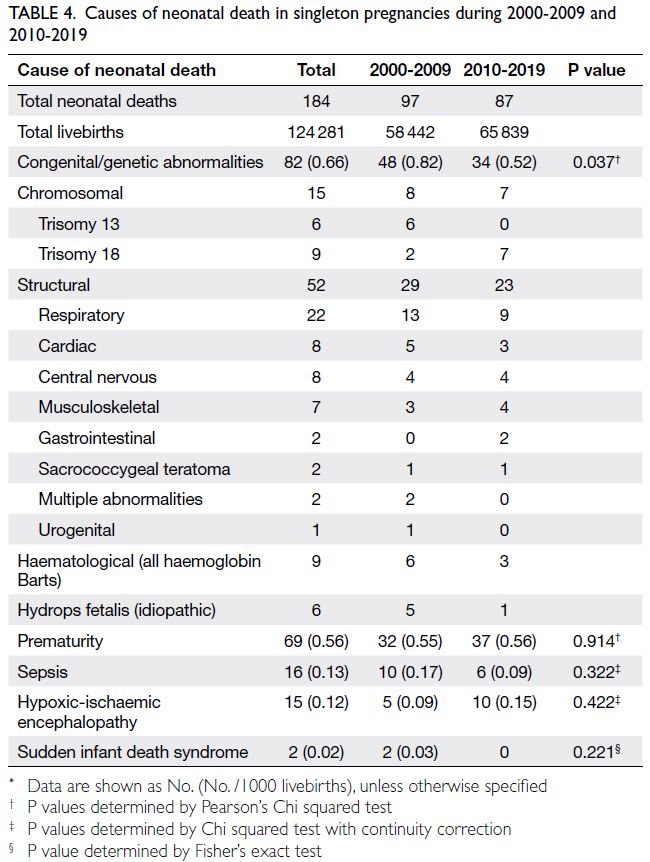

Antiemetic efficacies during cycle 1 of AC in the olanzapine and NEPA groups are shown in Table 3.

Complete response rates in acute, delayed, and

overall phases in cycle 1 did not differ between

groups. In the acute phase, the olanzapine group

exhibited a higher rate of ‘no use of rescue therapy’

(olanzapine vs NEPA: 96.7% vs 85.0%, P=0.0225). No

parameters differed between groups in the delayed

phase. In the overall phase, the olanzapine group

exhibited significantly higher rates of ‘no use of

rescue therapy’ (91.7% vs 76.7%, P=0.0244) and ‘no

significant nausea’ (91.7% vs 78.3%, P=0.0408).

Table 3. Comparison of antiemetic efficacy during cycle 1 of doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide between olanzapine and netupitant/palonosetron groups

The median time to first vomiting was not

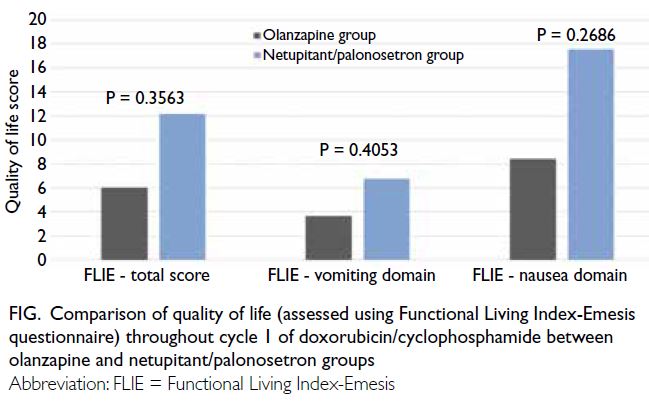

reached in either group (P=0.3902). Quality of

life results during cycle 1 of AC in the olanzapine

and NEPA groups, determined using the FLIE

questionnaire, are shown in the Figure. There were

no significant differences in the nausea domain,

vomiting domain, or total score of the FLIE

questionnaire between the two groups.

Figure. Comparison of quality of life (assessed using Functional Living Index-Emesis questionnaire) throughout cycle 1 of doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide between olanzapine and netupitant/palonosetron groups

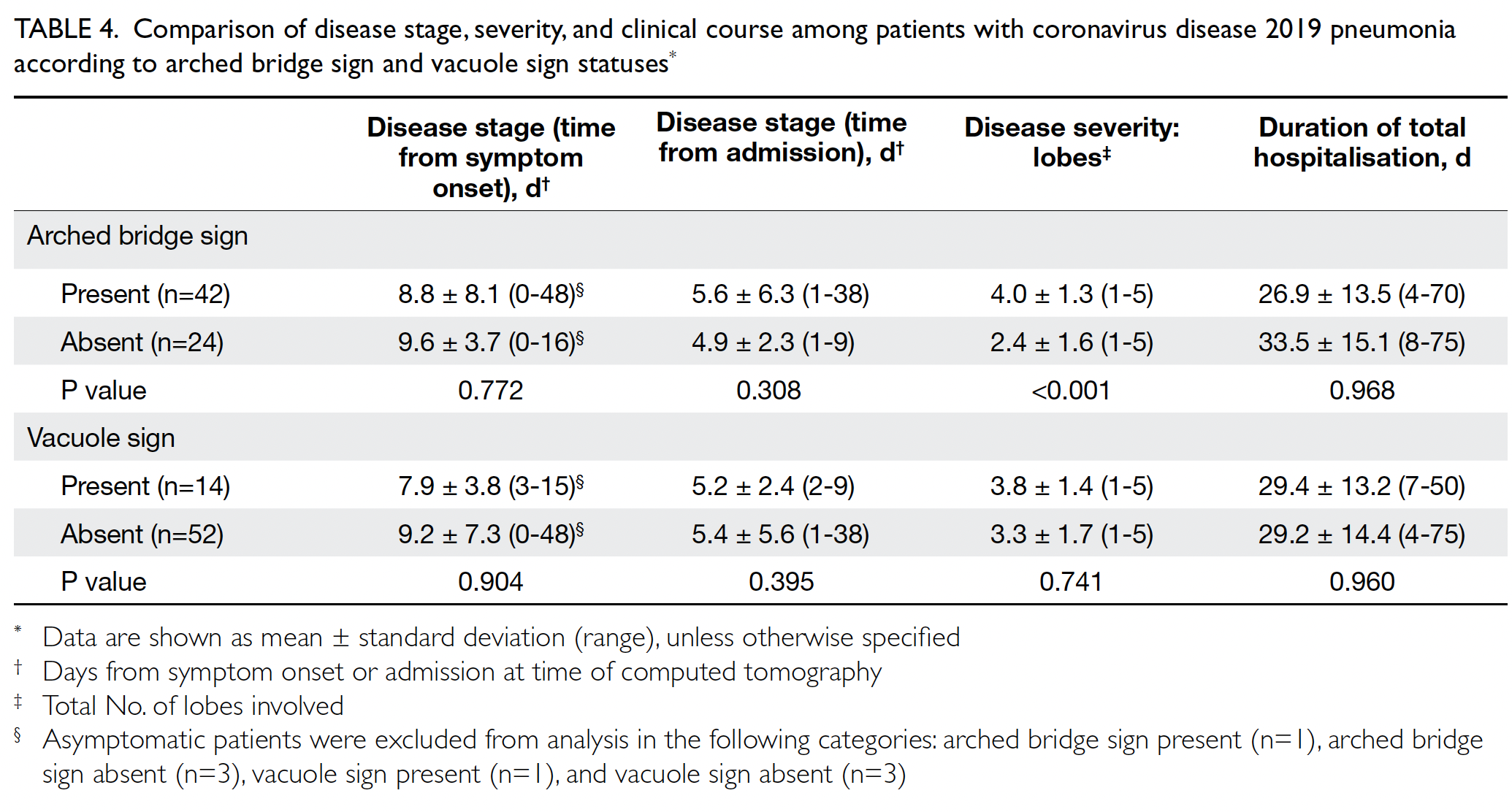

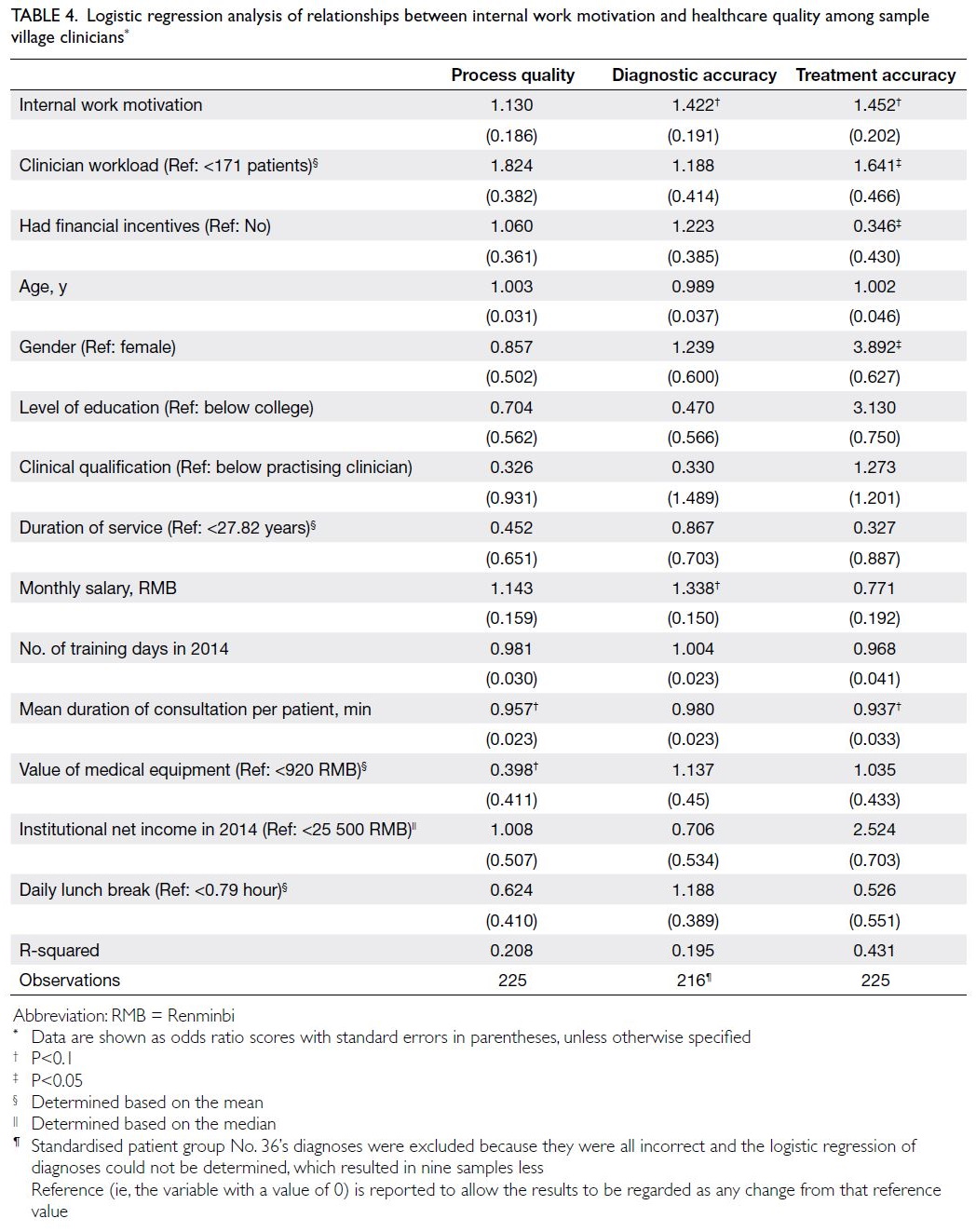

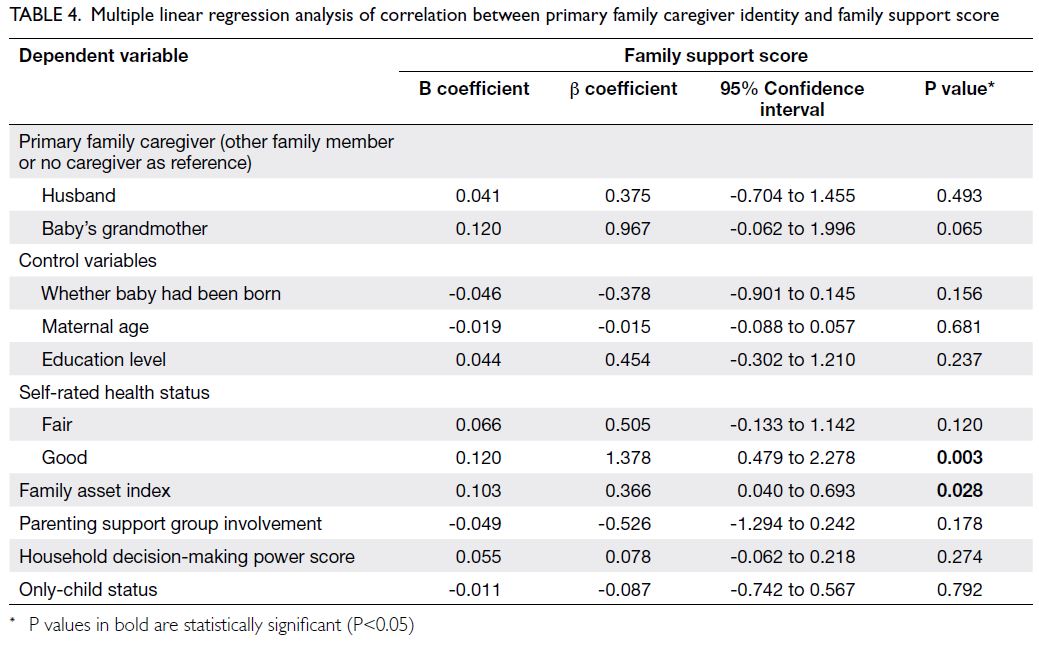

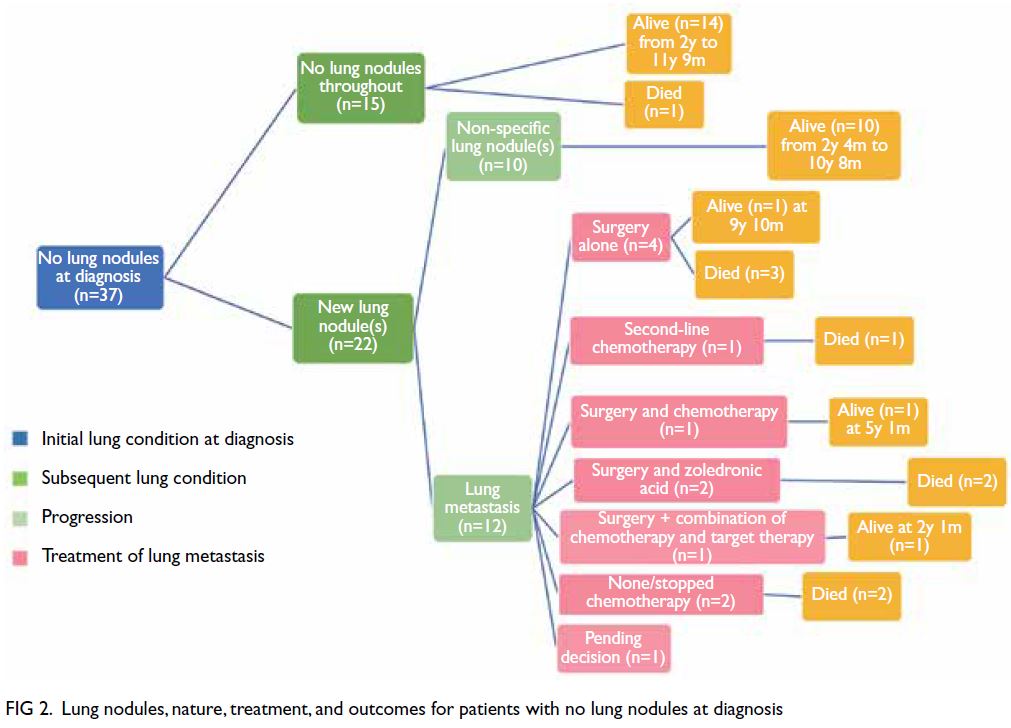

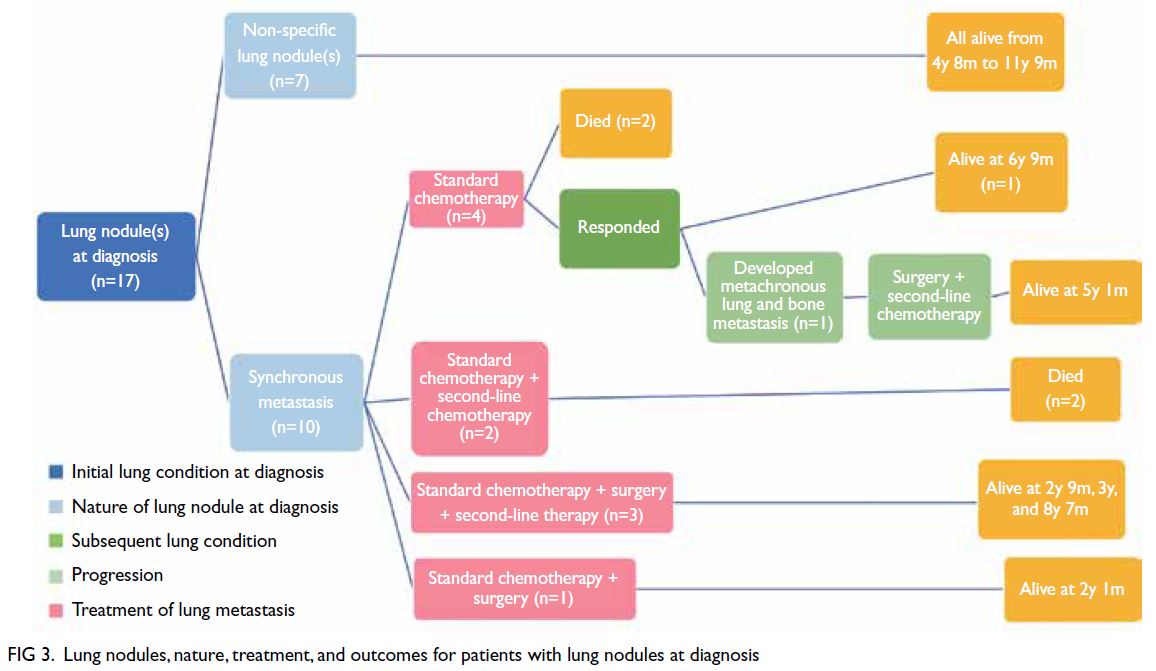

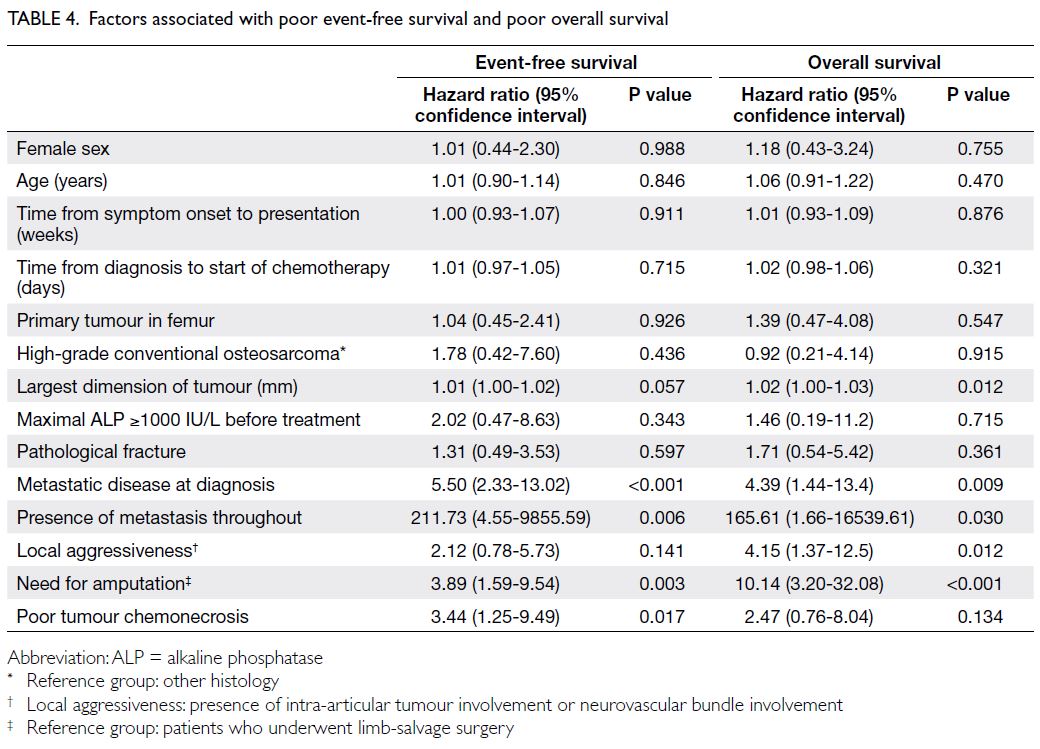

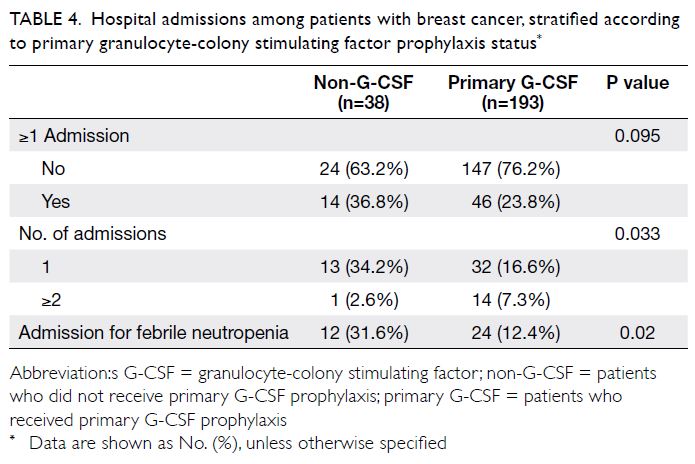

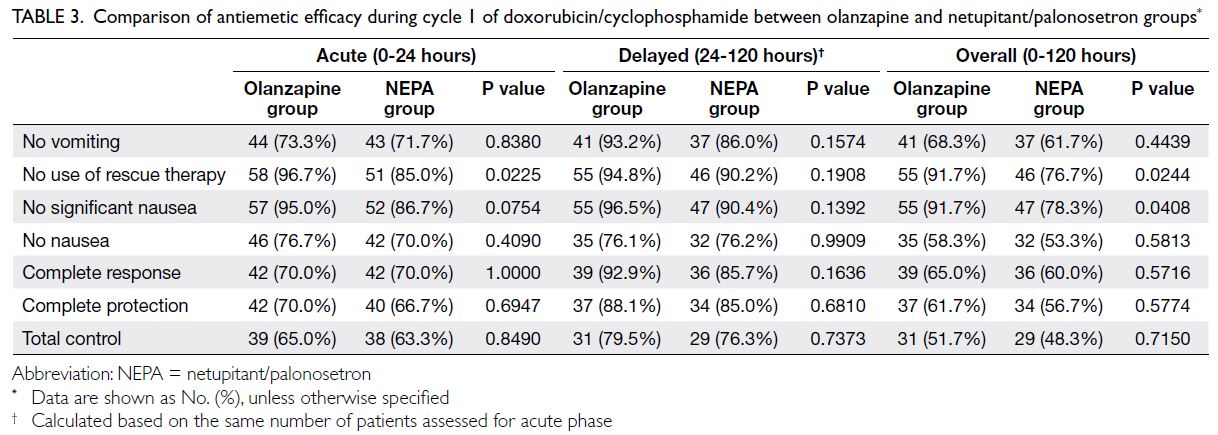

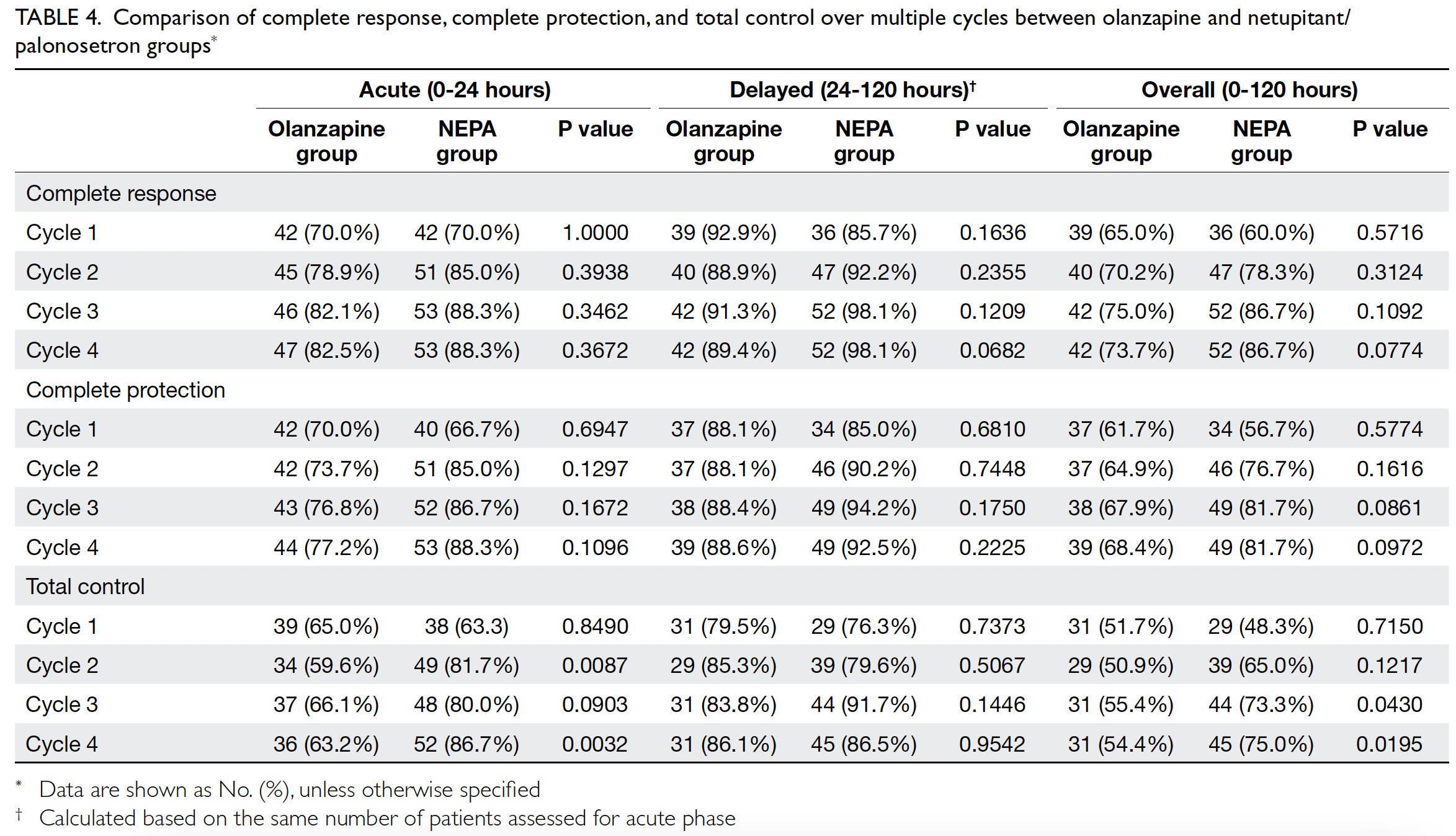

Antiemetic efficacies over multiple cycles of

AC in the olanzapine and NEPA groups are shown

in Table 4. In the acute phase, the NEPA group

exhibited significantly higher rates of total control

in cycle 2 (olanzapine vs NEPA: 59.6% vs 81.7%,

P=0.0087) and cycle 4 (63.2% vs 86.7%, P=0.0032).

No parameters differed between groups in the

delayed phase. In the overall phase, the NEPA group

exhibited significantly higher rates of total control

in cycle 3 (55.4% vs 73.3%, P=0.0430) and cycle 4

(54.4% vs 75.0%, P=0.0195).

Table 4. Comparison of complete response, complete protection, and total control over multiple cycles between olanzapine and netupitant/palonosetron groups

Discussion

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting is

a frustrating adverse effect for patients receiving

anticancer treatment.13 The administration of

optimal antiemetic prophylaxis can help to

maintain QOL, while potentially improving patient

compliance in terms of completing planned

therapies. In current antiemetic prophylaxis

guidelines, the European Society of Medical

Oncology/Multinational Association of Supportive

Care in Cancer, the American Society of Clinical

Oncology, and the United States National

Comprehensive Cancer Network offer several

options regarding antiemetic regimens for patients

receiving AC(-like) chemotherapy. These options

mainly involve the combination of a 5HT3RA and

corticosteroids, with or without an NK1RA and

olanzapine.2 3 4 In particular, the incorporation of

olanzapine, an antipsychotic drug with antagonistic

effects on various receptors (eg, dopamine and

serotonin receptors),14 is increasingly regarded as a

component of antiemetic prophylaxis for patients

receiving anticancer treatment.

In an attempt to identify the best antiemetic

regimen, Yokoe et al8 conducted a meta-analysis

of randomised trials that tested various antiemetic

regimens. The results indicated that olanzapine-based

regimens demonstrated the best efficacy.

Specifically, olanzapine in combination with

an NK1RA, a 5HT3RA, and dexamethasone

exhibited the greatest efficacy; other olanzapine-containing

regimens (consisting of a 5HT3RA and

dexamethasone) were also superior to regimens that

lacked olanzapine. Moreover, even in the presence

of earlier NK1RAs (eg, aprepitant, fosaprepitant, or

rolapitant), regimens lacking olanzapine remained

inferior.

Similar to the findings with olanzapine, Yokoe

et al8 reported that triplet antiemetics involving NEPA were superior to conventional NK1RAs

(eg, aprepitant, fosaprepitant, or rolapitant).

Furthermore, Zhang et al15 directly compared NEPA-based

antiemetic regimens with aprepitant-based

triplet regimens in a randomised study that involved

800 patients who underwent administration of a

cisplatin-containing regimen. Their results revealed

that patients receiving NEPA and dexamethasone

exhibited similar control of CINV, compared with

patients receiving aprepitant, granisetron, and

dexamethasone; however, NEPA-treated patients

had a significantly lower requirement for rescue

therapy. Additionally, in a recent study focused on

patients with breast cancer who were undergoing

AC chemotherapy, patients who received NEPA and

dexamethasone demonstrated significantly higher

rates of complete response, complete protection,

and total control with enhanced QOL, compared

to historical controls who received aprepitant,

ondansetron, and dexamethasone; these benefits

persisted over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.10

To our knowledge, no study has directly

compared olanzapine- and NEPA-containing

regimens. Using an indirect comparison approach,

the present study showed that the olanzapine-based

regimen had higher rates of ‘no use of rescue

therapy’ and ‘no significant nausea’ in cycle 1 of AC,

compared to the NEPA-based regimen. In contrast,

assessments in subsequent cycles revealed that the

NEPA-based regimen led to higher rates of total

control in the acute phase (cycles 2 and 4) and the

overall phase (cycles 3 and 4). The lack of difference

in QOL between the two groups of patients may be

related to the difference in adverse-effect profiles of

the antiemetics used. For instance, the continued use

of dexamethasone on days 2-3 in the NEPA group may

have affected QOL among those patients because

of its effects on mood, insomnia, gastrointestinal

symptoms, and metabolic profiles.16 Indeed, a recent

meta-analysis showed that, among patients receiving

AC or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy, 3 days

of dexamethasone did not provide additional benefit

compared to 1 day of the agent.17 However, olanzapine

has been associated with sedation and somnolence.18

Thus, after the completion of a phase 2 trial in Japan

that suggested olanzapine was more effective at 5 mg

than at 10 mg,19 the same group of investigators

conducted a phase 3 study in which they tested the

addition of daily olanzapine 5 mg to an aprepitant-based

three-drug regimen; the results showed that,

even at a lower dose of olanzapine, the olanzapine-containing regimen remained more efficacious

than the olanzapine-free regimen for patients

receiving cisplatin.20 Other adverse effects have been

reported. Our analysis of olanzapine in combination

with aprepitant, ondansetron and dexamethasone

revealed a significantly higher incidence of grade

≥2 neutropenia in the olanzapine arm than in

the standard arm, although this altered incidence

was not associated with a significant difference

in neutropenic fever.9 A few cases of olanzapine-induced

neutropenia have been reported21;

additionally, a recent randomised antiemetic study

showed that patients who received an olanzapine-containing

regimen had a higher frequency of

severe neutropenia (without an increased incidence

of neutropenic fever).22 Although the underlying

mechanism remains unknown, the results of the

aforementioned Japanese study20 suggest that

olanzapine 5 mg could reduce the incidence of

neutropenia. In contrast, in our previous trial

regarding a NEPA-based regimen, we found that

patients in the NEPA arm had significantly lower

incidences of grade ≥2 neutropenia and neutropenic

fever, compared to historical controls who received

an aprepitant-based regimen.9 10

This study had some potential limitations.

First, dexamethasone was only used for 1 day in

the olanzapine-based regimen, whereas it was

administered for 3 days in the NEPA-based regimen;

this difference may have influenced the findings. Second, the use of data from two separate studies

may have affected the generalisability of the findings

because of slight variations in patient characteristics;

the lack of blinding in both studies also increased

the potential for patient-related reporting biases.

Nonetheless, the original studies were consecutively

conducted during the period from 2017 to 2019;

both the data from Chinese patients enrolled in a

homogenous group with early-stage breast cancer

who were receiving (neo)adjuvant AC chemotherapy

and the present analysis were analysed based on

individual patient data. These factors support the

validity of our comparison approach.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present findings do not

conclusively support the superiority of either

the olanzapine-based regimen or the NEPA-based

regimen in terms of antiemetic efficacy or

QOL among patients with breast cancer who are

receiving AC. Our previous study demonstrated

that aprepitant has a limited effect when used with

a 5HT3RA and dexamethasone23; we also found

that NEPA was superior to aprepitant.10 Overall, the

available data suggest that olanzapine-containing

antiemetic regimens can be used without aprepitant,

particularly when seeking to reduce medical

expenses. Moreover, the available data support the

previous conclusion that, in parts of the world where

socio-economic limitations restrict the availability

of NK1RAs, the use of olanzapine combined

with a 5HT3RA and dexamethasone may be an

effective low-cost alternative antiemetic regimen.8 24

Antiemetic efficacy may be enhanced if NEPA is

administered in combination with dexamethasone

and olanzapine as a four-drug antiemetic regimen;

however, the efficacy of an olanzapine plus NEPA

regimen in terms of controlling CINV should be

confirmed in a trial setting.

Author contributions

Concept or design: W Yeo.

Acquisition of data: FKF Mo, W Yeo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: W Yeo, CCH Yip, FKF Mo.

Drafting of the manuscript: W Yeo, CCH Yip.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: L Li, TKH Lau, VTC Chan, CCH Kwok, JJS Suen, FKF Mo.

Acquisition of data: FKF Mo, W Yeo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: W Yeo, CCH Yip, FKF Mo.

Drafting of the manuscript: W Yeo, CCH Yip.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: L Li, TKH Lau, VTC Chan, CCH Kwok, JJS Suen, FKF Mo.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

W Yeo has been involved in the Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV) Network in Asia and

has provided lectures on CINV at events organised by

Mundipharma International Limited, which supported the

design of the NEPA study10 analysed in this post-hoc analysis but had no role in the present comparative analysis, data

collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of

the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We thank Ms Dong KT Lai, Ms Elizabeth Pang, Ms Vivian Chan, and Ms Maggie Cheung of the Department of Clinical

Oncology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong for their

support in contributing to patient enrolment and study

monitoring.

Declaration

Data from this study were presented at the European Society of Medical Oncology Asia Virtual Congress 2020 on 27

November 2020.

Funding/support

This study was supported by an education grant from Madam Diana Hon Fun Kong Donation for Cancer Research (Grant

No.: CUHK Project Code 7104870). The Donation had no

role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to

publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

The studies examined in this post-hoc analysis were approved

by The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New

Territories East Cluster Institution Review Board of The

Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority, and the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics

Committee of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority (Ref No.:

CREC 2016.013, CREC 2017.1609 and KW/FR-18-019[119-19]). All patient data in this study were anonymous and were

based on the abovementioned reported studies. There was no

additional work on retrieving patient records in this study.

References

1. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group

(EBCTCG); Peto R, Davies C, et al. Comparisons

between different polychemotherapy regimens for early

breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome

among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet

2012;379:432-44. Crossref

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical

Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Antiemesis Version 1; 2019.

3. Herrstedt J, Roila F, Warr D, et al. 2016 updated MASCC/ESMO consensus recommendations: prevention of nausea

and vomiting following high emetic risk chemotherapy.

Support Care Cancer 2017;25:277-88. Crossref

4. Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al. Antiemetics: American

Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline

update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3240-61. Crossref

5. Popovic M, Warr DG, Deangelis C, et al. Efficacy and safety

of palonosetron for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced

nausea and vomiting (CINV): a systematic review

and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support

Care Cancer 2014;22:1685-97. Crossref

6. Thomas AG, Stathis M, Rojas C, Slusher BS. Netupitant

and palonosetron trigger NK1 receptor internalization in

NG108-15 cells. Exp Brain Res 2014;232:2637-44. Crossref

7. Stathis M, Pietra C, Rojas C, Slusher BS. Inhibition of substance P-mediated responses in NG108-15 cells by netupitant and palonosetron exhibit synergistic effects.

Eur J Pharmacol 2012;689:25-30. Crossref

8. Yokoe T, Hayashida T, Nagayama A, et al. Effectiveness of

antiemetic regimens for highly emetogenic chemotherapy-induced

nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and

network meta-analysis. Oncologist 2019;24:e347-57. Crossref

9. Yeo W, Lau TK, Li L, et al. A randomized study of

olanzapine-containing versus standard antiemetic

regimens for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced

nausea and vomiting in Chinese breast cancer patients.

Breast 2020;50:30-8. Crossref

10. Yeo W, Lau TK, Kwok CC, et al. NEPA efficacy and tolerability during (neo)adjuvant breast cancer

chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin.

BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12:e264-70.

11. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Therapy Evaluation

Program. 2021. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40. Accessed 3 Feb 2023.

12. Martin AR, Pearson JD, Cai B, Elmer M, Horgan K,

Lindley C. Assessing the impact of chemotherapy-induced

nausea and vomiting on patients’ daily lives: a modified

version of the Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE) with

5-day recall. Support Care Cancer 2003;11:522-7. Crossref

13. Griffin AM, Butow PN, Coates AS, et al. On the receiving

end. V: patient perceptions of the side effects of cancer

chemotherapy in 1993. Ann Oncol 1996;7:189-95. Crossref

14. Bymaster FP, Nelson DL, DeLapp NW, et al. Antagonism

by olanzapine of dopamine D1, serotonin2, muscarinic,

histamine H1 and alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in vitro.

Schizophr Res 1999;37:107-22. Crossref

15. Zhang L, Lu S, Feng J, et al. A randomized phase III

study evaluating the efficacy of single-dose NEPA,

a fixed antiemetic combination of netupitant and

palonosetron, versus an aprepitant regimen for prevention

of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV)

in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy

(HEC). Ann Oncol 2018;29:452-8. Crossref

16. Roila F, Ruggeri B, Ballatori E, et al. Aprepitant versus metoclopramide, both combined with dexamethasone, for the prevention of cisplatin-induced delayed emesis: a

randomized, double-blind study. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1248-53. Crossref

17. Okada Y, Oba K, Furukawa N, et al. One-day versus three-day

dexamethasone in combination with palonosetron

for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and

vomiting: a systematic review and individual patient data-based

meta-analysis. Oncologist 2019;24:1593-600. Crossref

18. Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, et al. Olanzapine for the

prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

N Engl J Med 2016;375:134-42. Crossref

19. Abe M, Hirashima Y, Kasamatsu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety

of olanzapine combined with aprepitant, palonosetron,

and dexamethasone for preventing nausea and vomiting

induced by cisplatin-based chemotherapy in gynecological

cancer: KCOG-G1301 phase II trial. Support Care Cancer

2016;24:675-82. Crossref

20. Hashimoto H, Abe M, Tokuyama O, et al. Olanzapine

5 mg plus standard antiemetic therapy for the prevention of

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (J-FORCE):

a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:242-9. Crossref

21. Malhotra K, Vu P, Wang DH, Lai H, Faziola LR. Olanzapine-induced neutropenia. Ment Illn 2015;7:5871. Crossref

22. Gjafa E, Ng K, Grunewald T, et al. Neutropenic sepsis rates

in patients receiving bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin

chemotherapy using olanzapine and reduced doses of

dexamethasone compared to a standard antiemetic

regimen. BJU Int 2021;127:205-11. Crossref

23. Yeo W, Mo FK, Suen JJ, et al. A randomized study

of aprepitant, ondansetron and dexamethasone for

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Chinese

breast cancer patients receiving moderately emetogenic

chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:529-35. Crossref

24. Babu G, Saldanha SC, Kuntegowdanahalli

Chinnagiriyappa L, et al. The efficacy, safety, and

cost benefit of olanzapine versus aprepitant in highly

emetogenic chemotherapy: a pilot study from South India.

Chemother Res Pract 2016;2016:3439707. Crossref