Hong Kong Med J 2022;28(6):457–65 | Epub 7 Dec 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE (HEALTHCARE IN MAINLAND CHINA)

Correlation between primary family caregiver

identity and maternal depression risk in poor rural China

N Wang, PhD; M Mu, MSc; Z Liu, MSc; Z Reheman, MSc; J Yang, PhD; W Nie, MSc; Y Shi, PhD; J Nie, PhD

Center for Experimental Economics in Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

Corresponding author: Dr J Yang (jyang0716@163.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Prenatal and postpartum depression

are important public health challenges because

of their long-term adverse impacts on maternal

and neonatal health. This study investigated the

risk of maternal depression among pregnant and

postpartum women in poor rural China, along with

the correlation between primary family caregiver

identity and maternal depression risk.

Methods: Pregnant women and new mothers

were randomly selected from poor rural villages

in the Qinba Mountains area in Shaanxi. Basic

demographic information was collected regarding

the women and their primary family caregivers.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was used

to identify women at risk of depression, and the

Perceived Social Support Scale was used to evaluate

perceived family support.

Results: This study included 220 pregnant women and

473 new mothers. The mean proportions of women

at risk of prenatal and postpartum depression were

19.5% and 18.6%, respectively. Regression analysis

showed that identification of the baby’s grandmother

as the primary family caregiver was negatively

correlated with maternal depression risk (β=-0.979,

95% confidence interval [CI]=-1.946 to -0.012,

P=0.047). However, the husband’s involvement in that role was not significantly correlated with

maternal depression risk (β=-0.499, 95% CI=-1.579

to 0.581, P=0.363). Identification of the baby’s

grandmother as the primary family caregiver was

positively correlated with family support score

(β=0.967, 95% CI=-0.062 to 1.996, P=0.065).

Conclusion: Prenatal and postpartum depression

are prevalent in poor rural China. The involvement

of the baby’s grandmother as the primary family

caregiver may reduce maternal depression risk, but

the husband’s involvement in that role has no effect.

New knowledge added by this study

- Prenatal and postpartum depression are prevalent in poor rural areas of China. Despite evidence regarding the importance of family support during prenatal and postpartum periods, husbands in poor rural China did not provide effective support.

- There was a persistent risk of maternal depression during both prenatal and postpartum periods.

- Maternal depression persists in the absence of external interventions.

- High-quality family support is necessary to ensure that pregnant women maintain good mental health. Compared with husbands, grandmothers may be better primary caregivers because they are experienced in terms of parenting and housework.

- Husbands in poor rural China should receive training that enables them to provide effective maternal care.

Introduction

Maternal depression is a common mental health

problem during the prenatal and postpartum

periods. The World Health Organization estimates

that approximately 10% of pregnant women and

13% of postpartum women worldwide have mental health problems, mainly depression.1 In China, the

prevalence of maternal depression ranges from

8.2% to 28.5%.2 3 4 5 6 7 Women in urban areas have access

to specialised maternity care services and mental

health services that can help manage these mental

health problems and difficulties.8 However, these commercialised services are usually expensive and

distant from poor rural areas of China. Therefore, it is

particularly important for pregnant and postpartum

women in poor rural areas to rely on family and

social relationships for reasonable care and support.

There is evidence that the level of perceived

social support, particularly family support, is

associated with a woman’s mental health status

during pregnancy.9 10 China’s rapid societal and

economic development have resulted in substantial

changes to family structure in both urban and rural

areas. For example, modern couples are more likely

to live with only their children, rather than with

family members from multiple generations.11 When

grandparents are absent from a family’s daily life,

the role of the husband becomes more important

because he must be more engaged in housework12 and provide greater support.

The changes in primary family caregiver

identity during prenatal and postpartum periods

reflect this transformation of family structure.13 The

results of multiple studies in developed countries

and the urban areas of China have suggested that

husbands are able to care for their wives and children

during pregnancy and after delivery; moreover, a

husband’s companionship has a positive impact on

the mental health status of his pregnant wife.2 10 14 However, in poor rural areas, no consensus has been

reached concerning whether a husband can provide

effective family support for his pregnant wife.15 For

example, husbands usually have lower awareness

of maternity care because of limited education

and limited housework experience. However, in a

traditional Chinese family with patrilocal features,

the husband is the main worker and is responsible

for the economic well-being of the family,16 whereas

the wife stays at home and cares for the family. This

stereotype of traditional household arrangement

prevents some men from providing maternal care,

regardless of their presence at home. Accordingly,

grandmother, the mother of the baby’s mother,

becomes a possible caregiver for the mother and

baby,17 although this may lead to mother-in-law conflict.18

Here, using data from a large-scale survey

of pregnant and postpartum women in poor rural

areas, we analysed the status of maternal mental

health in poor rural areas, with family support as an

intermediate variable, to understand the correlation

between primary family caregiver identity and

maternal depression risk.

Methods

Sampling

The data analysed in this study were collected

during a survey of maternal and neonatal health

and nutrition statuses among residents of poor rural

villages in the Qinba Mountains area; the survey

was conducted by Shaanxi Normal University from

March 2019 to April 2019. The Qinba Mountains

area spans six provinces including Gansu, Sichuan,

Shaanxi, Chongqing, Henan, and Hubei. Its primary

portion is situated in Shaanxi’s southern region. In

2019, the per capita annual disposable income in the

Qinba Mountains area was RMB 11 443, similar to

that of rural residents in poverty-stricken counties

(RMB 11 567).19 In 2018, the mean poverty rate in

this area was 3.6%; for comparison, the national

mean was 1.7% and the rate in poverty-stricken

counties was 4.5%.20 This study included women aged

≥18 years who were either pregnant (≥4 weeks of

gestation) or in the postpartum period (0-6 months

after delivery).

The following multilevel cluster-based random

sampling method was used in this study. First, 13

national-level poor counties in two prefectures in

the Qinba Mountains area were selected. Then, a

list of villages was obtained for each county, and the

total numbers of pregnant women and households

with babies aged ≤6 months in each village were

counted with assistance from local government

officials. Considering the financial limitations and

overall feasibility of the study, villages with a small

sample size (<3) or large sample size (>15) were excluded. Finally, we used Stata 15.0 (Stata Corp,

College Station [TX], United States) to analyse the

data. The sample size was estimated to achieve, for

an average incidence of independent variables of

0.15 in consideration of our pilot study, a sampling

standard error (SE) of 0.03 with a 95% confidence

interval (CI). The final 131 villages were randomly

selected as sample villages, and all households in

the sample villages that met the above criteria were

considered eligible for the study.

Data collection

The data used in this study were collected through

face-to-face interviews. To ensure accuracy and

consistency during data collection, enumerators

were selected from a group of interested university

students in Xi’an. The enumerators underwent

extensive training, then completed a pilot study

with 20 participants prior to formal data collection.

Each eligible participant received a consent form

with information regarding programme objectives,

procedures, potential risks, and benefits, as well as

an explanation of privacy protection. Participants

provided oral consent for inclusion in the study

before engaging in a face-to-face interview with a

single enumerator. Each interview only involved

the participant, and interruptions from other family

members were avoided.

Assessments

Basic participant information

A questionnaire was used to collect basic participant

information, including their age, education level,

and self-rated health status, along with whether the

baby had been born and whether it was the firstborn

child. The women were also asked whether they had

access to any support groups where mothers could

seek help and exchange information concerning

parenting experiences. Furthermore, they were

asked nine yes/no questions regarding family assets

(eg, possession of a computer, an air conditioner, and

a car). The above questions were also included in our

questionnaire to better understand maternal social

interactions and household assets in order to control

for them in the regression analysis and thus produce

more accurate regression results. Each participant’s

decision-making power was measured using a

scale of eight items compiled by Peterman et al.21

A higher score on the decision-making power

scale was presumed to indicate greater autonomy

concerning childcare and the management of other

family issues.

Primary family caregivers

A questionnaire was used to collect information

about all family members living in the participant’s

home for >3 months, who were more likely to be the primary caregivers and to have an impact on

maternity. Each participant was asked to identify

the family member who served as the primary

family caregiver, providing the most care for the

participant and her baby during the prenatal and

postpartum periods. Considering the sample size

and sample distribution, three primary family

caregiver categories were used in this study: the

husband, the baby’s grandmother (the mother of the

baby's mother or the baby's father), and other family

members or no caregivers.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

is a 10-item scale used to identify women at risk of

maternal depression.22 23 The total EPDS score ranges

from 0 to 30, where a higher score indicates a greater

risk of depression. Although the original cut-off

value was an EPDS score of ≥13 points, we used the

standard cut-off value in China (≥9.5 points24 25) as

an indicator of sufficient depression risk to merit

psychiatric examination and possible treatment.

Previous research has demonstrated that the EPDS

has satisfactory reliability and validity. Specifically,

Wang et al26 reported that the EPDS had a content

validity ratio of 0.93 and good internal consistency

(Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.76). The correlation

coefficients between the 10 individual item scores

and the total score ranged from 0.37 to 0.67, with P

values <0.01.

Perceived Social Support Scale

The Perceived Social Support Scale, developed by

Zimet et al27 and translated into Chinese by Jiang,28

is a 12-item self-assessment questionnaire that

measures three sources of social support (ie, three

subscales): family support, friends’ support, and

other people’s support. Responses to questionnaire

items are recorded using a seven-point Likert scale

that ranges from ‘completely negative’ to ‘completely

positive’ (1-7 points), indicating the respondent’s

level of agreement with each item. The total score

is 84 points (28 points per subscale), and a higher

score indicates the receipt of greater social support.

The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale is 0.88; the

Cronbach’s α coefficients for family support, friends’

support, and other people’s support subscales are

0.81, 0.85, and 0.91, respectively.27 Because this study

focused on family support, only the family support

subscale was used as an intermediate variable to

analyse the correlation between primary family

caregiver identity and maternal depression risk.

Statistical methods

STATA 15.1 software was used to clean the data and

perform statistical analysis. Descriptive statistical

analysis was performed and presented as mean ± standard deviation. F-test and t test were used

to detect differences in depression scores among

subgroups of women with different characteristics.

Multiple linear regression was used to explore

correlations between primary family caregiver

identity and maternal depression risk or family

support score. P values <0.05 were considered

statistically significant. Additionally, we adjusted the

SE at the village level and calculated coefficients with

greater precision because individual values within

the same village are correlated, which might result in

biased SE in multiple linear regression.

Results

In total, 715 women were interviewed, including 220

pregnant women and 495 new mothers. Twenty-two

samples with missing values were excluded to

ensure sample uniformity throughout the analysis

procedure. Finally, analyses in this study were based

on the data of 693 participants (220 pregnant women

and 473 new mothers) and the questionnaire return

efficiency was 96.9%, which is the percentage of

survey responses that were valid.

Maternal depression risk in poor rural areas

Among the 220 pregnant women, 37 (16.8%), 66

(30.0%), and 117 (53.2%) were in the early, middle,

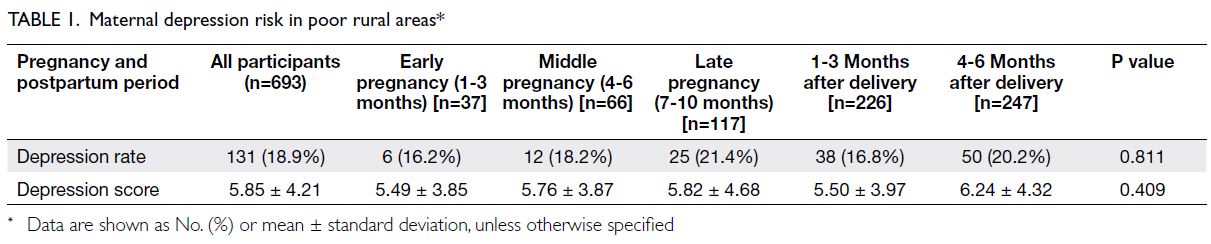

and late stages of pregnancy, respectively (Table 1).

In total, 226 of the 473 new mothers (47.8%) had

babies aged 1 to 3 months, whereas 247 new mothers

(52.2%) had babies aged 4 to 6 months.

The mean maternal EPDS score was 5.85

and the proportion of women at risk of depression

was 18.9% (131/693). The proportion of women at

risk of depression was generally stable regardless

of pregnancy stage. Specifically, the proportion of

women at risk of depression during early pregnancy

was 16.2% (6/37); during middle and late pregnancy,

the proportions of women at risk were slightly

increased. The proportions of women at risk of

depression were 16.8% (38/226) and 20.2% (50/247)

at 1-3 months and 4-6 months after delivery,

respectively. However, the maternal EPDS scores

and proportions of women at risk of depression did

not significantly differ according to pregnancy stage

or time since delivery.

Univariate analysis of maternal depression

risk

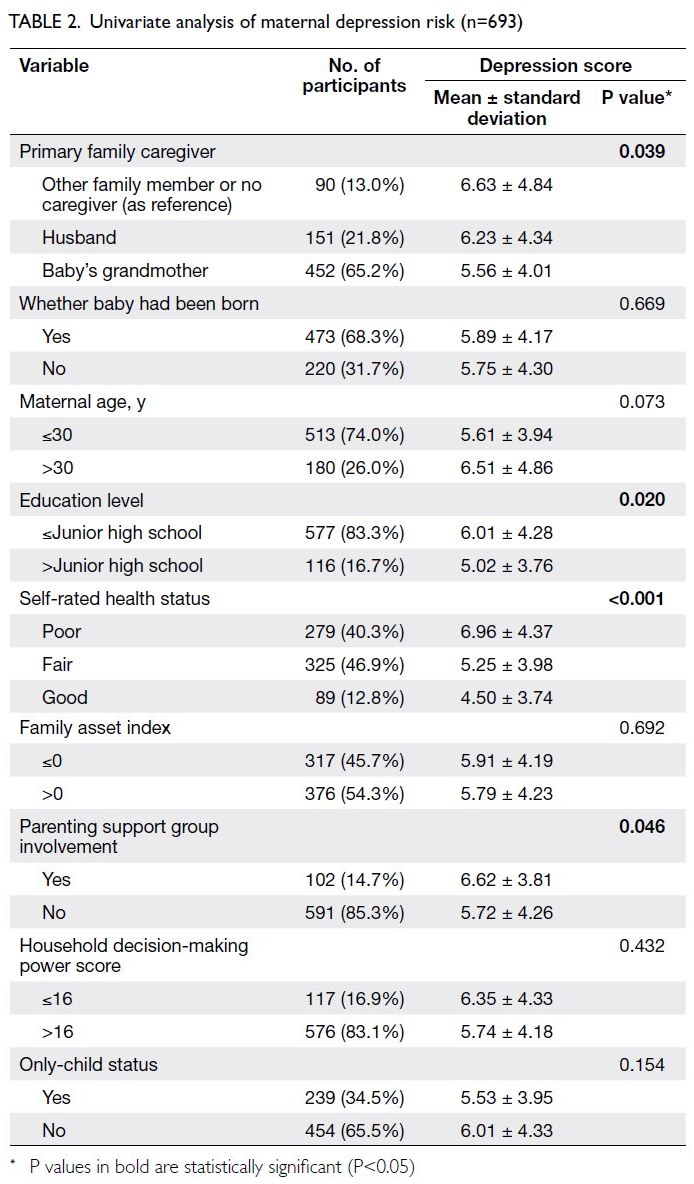

Overall, the mean participant age was 28.13 ± 4.70

years. In total, 239 women (34.5%; mean age, 25.52

± 3.95 years) reported that the current pregnancy

or ≤6-month-old baby was their firstborn child. The

remaining 454 women (65.5%; mean age, 29.50 ± 4.49

years) were experienced mothers who have already

had children and are familiar with caring for them.

Overall, 116 women (16.7%) had an education level

above junior high school. The self-rated health status

was good in 89 women (12.8%), and 102 women

(14.7%) were involved in a parenting support group.

Table 2 summarises the participant characteristics.

As shown in Table 2, the participants were

clustered into three groups according to primary

caregiver identity: the husband for 151 women

(21.8%), the baby’s grandmother for 452 women

(65.2%), and other family members or no caregiver

for 90 women (13.0%). The mean EPDS scores

of women in the three groups were 6.23 ± 4.34,

5.56 ± 4.01, and 6.63 ± 4.84, respectively (P=0.039).

Additionally, univariate analysis revealed statistically

significant differences in depression scores according

to education level, self-rated health status, and

parenting support group involvement. There were no

statistically significant differences in other variables.

Correlation between primary family

caregiver identity and maternal depression

risk

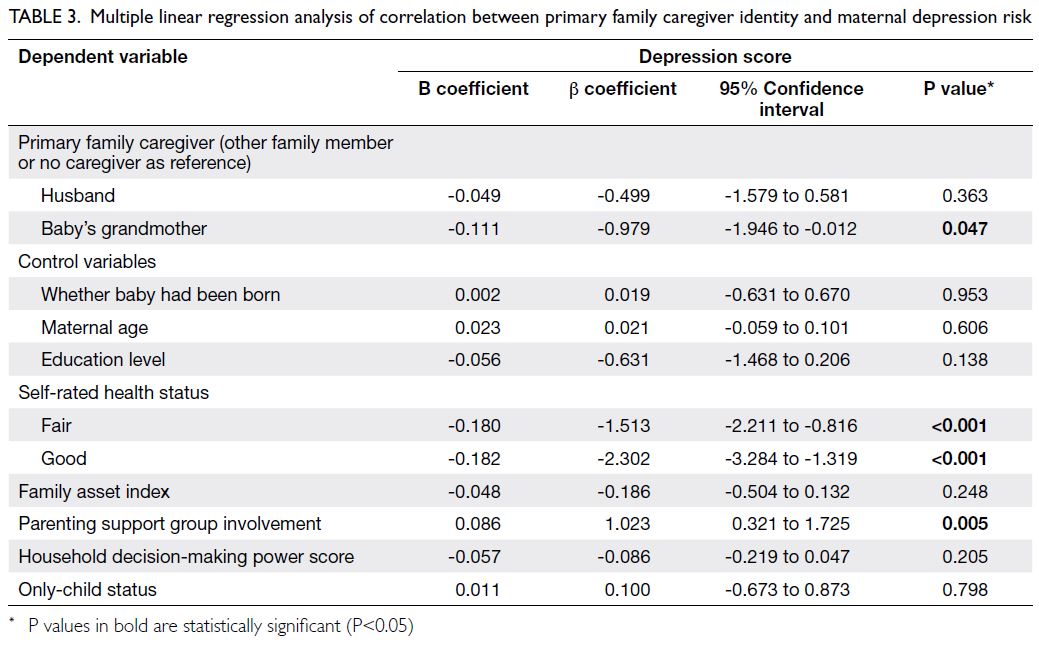

As shown in Table 3, identification of the baby’s

grandmother as the primary family caregiver was

significantly negatively correlated with EPDS score

(β=-0.979, 95% CI=-1.946 to -0.012, P=0.047).

However, identification of the husband as the family

caregiver was not significantly correlated with EPDS

score (β=-0.499, 95% CI=-1.579 to 0.581, P=0.363).

Table 3. Multiple linear regression analysis of correlation between primary family caregiver identity and maternal depression risk

Correlation between primary family

caregiver identity and family support score

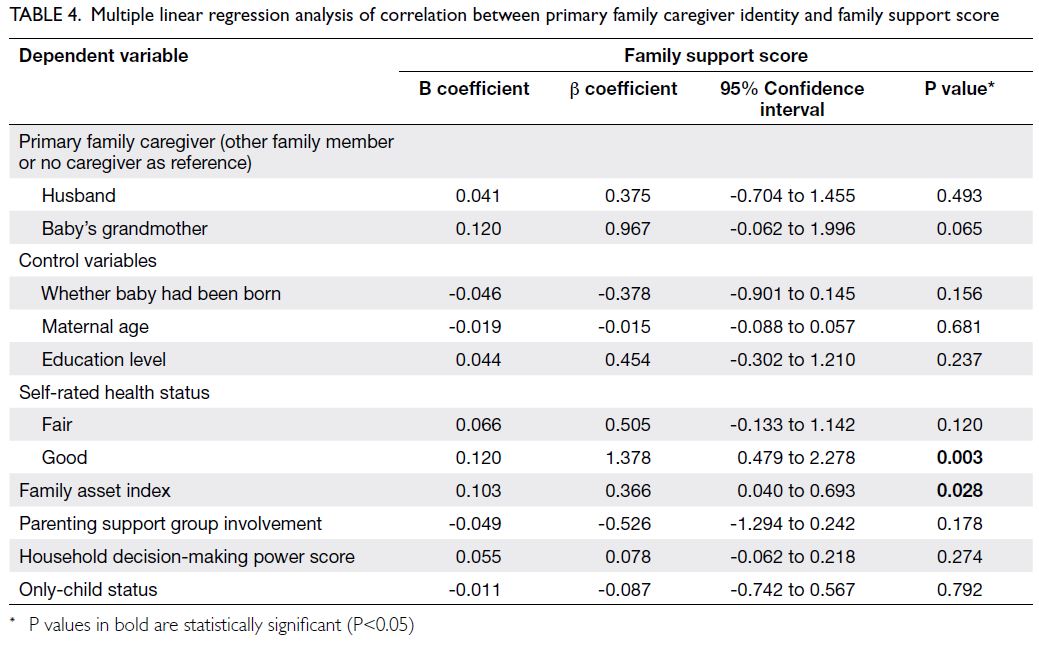

As shown in Table 4, after adjustment for other

variables, there was no significant correlation between

identification of the husband as the primary family

caregiver and the family support score (β=0.375,

95% CI=-0.704 to 1.455, P=0.493). However, identification of the baby’s grandmother as the

primary family caregiver was significantly positively

correlated with family support score (β=0.967,

95% CI=-0.062 to 1.996, P=0.065). Furthermore,

identification of the baby’s grandmother as the

primary family caregiver had the largest standardised

regression coefficient among the three caregiver

categories, indicating that pregnant and postpartum

women felt the greatest family support when

the baby’s grandmother was the primary family

caregiver.

Table 4. Multiple linear regression analysis of correlation between primary family caregiver identity and family support score

Discussion

Maternal depression risk in poor rural areas

In this study, the overall proportion of women at

risk of maternal depression was 18.9%, including a

mean proportion of 19.5% among pregnant women

and a mean proportion of 18.6% among women

≤6 months postpartum. This overall proportion of

women at risk of maternal depression is much higher

than the proportion in a western urban area of China

(12.4%)29 and comparable with the proportions in

low- and middle-income countries such as Ethiopia

(19.9%)30—both previous studies also used the EPDS

to identify women at risk of maternal depression. The

high proportion in the present study may be related

to the location (poor rural areas): compared with

women in urban areas, women in poor rural areas are

more likely to have a lower socio-economic status.31

The lack of knowledge regarding mental health

and its services in rural areas also makes women

in such areas more likely to become depressed if

they do not receive timely treatment for mental

health problems.32 Therefore, the mental health

of rural mothers should receive greater attention

from their family members and the relevant health

departments.

This study also revealed a persistent risk of

depression during the prenatal and postpartum

periods (Table 1). Notably, the proportion did not

substantially decrease by 6 months after delivery.

Yue et al33 investigated the mental health of

caregivers for babies aged 6 to 36 months in a rural

area in western China. Their results showed that the

proportion of caregivers at risk of depression was

similar to the proportion in the present study. These

findings suggest that maternal depression persists

in the absence of external intervention. Thus, there

is an urgent need for timely external mental health

interventions among pregnant women and mothers

of young children. The present study also showed

that the maternal depression risk in poor rural areas

is influenced by factors such as a woman’s education

level, self-rated health status, and parenting support

group involvement. These results are consistent with

the findings by Zhou et al,7 Lancaster et al,10 and

Lee et al.18

Correlation between primary family

caregiver identity and maternal depression risk

Our results showed that identification of the

husband as the primary family caregiver was not

significantly correlated with maternal depression

risk in poor rural areas (Table 3). This finding

was considerably different from the results of

previous studies in urban areas. Xie et al34 found

that insufficient or poor-quality emotional support

from the husband was significantly associated with

an increased risk of postpartum depression among mothers in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. In

contrast, Wan et al2 found that the proportions of

women at risk of maternal depression were 1.9- to

2.6-fold higher among women without support from

the husband before and after delivery than among

women with support from the husband, based on

a study of mothers in Beijing, China. The results of these studies suggest that the husband’s involvement

as the primary family caregiver can reduce the risk

of maternal depression in urban areas, but this effect

was not apparent in poor rural areas.

We also found that maternal depression risk was

significantly lower when the baby’s grandmother was

identified as the primary family caregiver (Table 3). Our results are consistent with the findings by Wan

et al2 in a study of 342 pregnant women in Beijing,

China: during the ‘confinement’ period, care and

support from the baby’s grandmother(s) were

important for relieving depression. However, Lee

et al18 showed that mother-in-law conflict remains

prominent in China, which may have negative

emotional outcomes for grandmothers and new

mothers. Although pregnant and postpartum women

in poor rural areas may experience similar conflict,

our findings suggest that support from the baby’s

grandmother(s) remains predominantly positive.

Correlation between family support and

maternal depression risk

We attempted to determine why support from

the husband did not reduce maternal depression

risk in poor rural areas through the analysis of an

intermediary variable. Initially, we hypothesised

that the positive effect of the husband acting as the

primary family caregiver would be offset by the loss

of income caused by the husband’s inability to seek

work opportunities in other locations. However,

data analysis revealed that the husband’s role as

the primary caregiver had no impact on the family

income and family asset index (online supplementary Table 1). Thus, we explored the effect of family

support. Multiple previous studies demonstrated

that family support influenced maternal depression

risk14; consistent with those findings, our analysis

showed that family support was significantly

negatively correlated with maternal depression risk

(online supplementary Table 2).

There may be two main reasons for this

negative correlation. First, husbands in poor rural

areas have insufficient knowledge and skills related

to maternal care.16 Husbands do not have first-hand

experience in childbirth and can only acquire it

through education. However, compared with men

in urban areas, men in poor rural areas have lower

levels of education and may be less inclined to learn

on their own, making it more difficult to acquire such

knowledge and skills.35 In contrast, grandmothers are

more experienced overall, which may enable them to

provide more effective family support. For example,

based on their own experience, grandmothers can

help new mothers to prepare for and manage pain

that sometimes occurs during breastfeeding, which

can alleviate anxiety and provide a feeling of greater

support.17 Second, in poor rural areas, husbands

may lack sufficient time and energy to provide

effective family care. Compared with families in

urban areas, families in poor rural areas are more

economically disadvantaged33; therefore, husbands

in such families may prioritise financial stability and

be unable to expend time or energy in support of

maternal care, despite their physical presence in the

home. In contrast, the baby’s grandmother(s) may have sufficient time and energy to provide effective

maternal care (eg, by feeding the baby and changing

its diapers), thus relieving the mother’s psychological

stress.

The findings in this analysis of women in poor

rural areas differ from the results of studies in urban

areas, indicating important differences in family

structure between urban and rural areas. There is

evidence that a gradual transformation of the family

is underway in urban areas, whereby husbands have

begun to actively engage in caregiving. However, the

transformation of family structure is much slower

in poor rural areas,13 and husbands in those areas

are not yet prepared for this new role. Because of

constraints regarding their education level and

skills, as well as family finances, husbands in poor

rural areas continue to prioritise financial stability36;

their support does not have a positive impact on

the risk of maternal depression. Thus, women in

poor rural areas must continue to rely on family

members outside of the nuclear family, such as the

baby’s grandmother(s), to assume some caregiving

responsibilities.

Commercialised and specialised mental health

counselling services in urban areas play important

roles in improving maternal mental health.8 Xiao37

found that postnatal care through a menstrual club

provided continuous physical, psychological, and

emotional support that was sufficient to reduce the

incidence of postpartum depression. However, such

clubs are not available in poor rural areas. Therefore,

it is important to promote better caregiving from

family members, including husbands. For example,

husbands could receive training that enables them

to provide practical support, as well as guidance

concerning the early identification of depressive

tendencies and the development of communication

skills for psychological adjustment.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevented the assessment of

maternal depression trends during pregnancy and

after delivery, although such an assessment could

have been conducted in a cohort study. Second, this

study focused on primary family caregiver identity

and did not explore the type or form of caregiving

provided. Third, all participants were residents of

rural northwest China, and thus the results may

not be generalisable to other populations. These

limitations should be addressed in future studies.

Conclusions and policy implications

The prevalence of maternal depression is high in poor rural areas of Shaanxi Province. Identification of the

husband as the family caregiver was not significantly correlated with maternal depression risk, whereas

the involvement of the baby’s grandmother in that

role was significantly negatively correlated with

maternal depression risk. Based on our findings,

we make the following suggestions. In rural areas,

high-quality family support is necessary to ensure

that pregnant women maintain good mental health.

Compared with husbands, grandmothers may be

better primary caregivers because they are more

experienced in terms of parenting and housework.

Husbands in poor rural China should receive training

that enables them to provide effective maternal care.

Author contributions

Concept or design: N Wang, M Mu, J Yang, Y Shi, J Nie.

Acquisition of data: N Wang, M Mu, Z Liu, R Zulihumaer, W Nie.

Analysis or interpretation of data: N Wang, M Mu, J Yang, J Nie.

Drafting of the manuscript: N Wang, M Mu, J Yang, Y Shi, J Nie.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: N Wang, M Mu, Z Liu, R Zulihumaer, W Nie.

Analysis or interpretation of data: N Wang, M Mu, J Yang, J Nie.

Drafting of the manuscript: N Wang, M Mu, J Yang, Y Shi, J Nie.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an International Editorial Advisory Board member of the journal, Y Shi was not involved in the peer review process.

Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the study participants and the enumerators who conducted data collection.

Funding/support

The authors are supported by the 111 Project (Grant No. B16031), Soft Science Research Project of Xi’an Science and

Technology Plan (Grant No. 2021-0059), the Fundamental

Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No.

2021CSWY024) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the

Central Universities (Grant No. 2021CSWY025) of China.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee

of Shaanxi Normal University and Xi’an Jiaotong University

of China (No: 2020-1240). Each eligible participant received

a consent form with information regarding programme

objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, as well

as an explanation of privacy protection. Participants provided

oral consent for inclusion in the study before engaging in a

face-to-face interview with a single enumerator.

References

1. Ceulemans M, Foulon V, Ngo E, et al. Mental health status

of pregnant and breastfeeding women during the COVID-

19 pandemic—a multinational cross-sectional study. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021;100:1219-29. Crossref

2. Wan EY, Moyer CA, Harlow SD, Fan Z, Jie Y, Yang H.

Postpartum depression and traditional postpartum care in

China: role of Zuoyuezi. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2009;104:209-13. Crossref

3. Zeng Y, Cui Y, Li J. Prevalence and predictors of antenatal

depressive symptoms among Chinese women in their

third trimester: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry

2015;15:66. Crossref

4. Zhang Y, Zou S, Cao Y, Zhang Y. Relationship between

domestic violence and postnatal depression among

pregnant Chinese women. Int J Gynecol Obstet

2012;116:26-30. Crossref

5. Song Y, Li W. The impact of social support and antepartum

emotion on postpartum depression [in Chinese]. China J

Health Psychol 2014;22:909-11.

6. Xu M, Li C, Zhang K, Sun S, Zhang H, Jin J. Comparison of

prenatal depression and social support differences between

Korean and Han pregnant women in Yanbian region [in

Chinese]. Matern Child Health Care China 2015;30:524-7.

7. Zhou X, Liu H, Li X, Zhang S, Li F, Zhao Z. Depression

and risk factors of women in their second-third trimester

of pregnancy in Shaanxi province [in Chinese]. Chin Nurs

Manage 2019;19:1005-11.

8. Liu H, Zhang C. Comparative study on service efficiency of

China’s urban and rural health systems [in Chinese]. China

Soft Sci 2011;10:102-13.

9. Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G, Corcoran P. First-time

mothers: social support, maternal parental self-efficacy

and postnatal depression. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:388-97. Crossref

10. Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM,

Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during

pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2010;202:5-14. Crossref

11. Tang C. A review of modernisation theory and its

development on family [in Chinese]. Sociol Stud

2010;25:199-222,246.

12. Högberg U. The World Health Report 2005: “make every

mother and child count”—including Africans. Scand J

Public Health 2005;33:409-11. Crossref

13. Zhao F, Ji Y, Chen F. Conjugal or parent-child relationship?

Factors influencing the main axis of Chinese family

relations in transition period [in Chinese]. J Chin Women

Stud 2021;4:97-112.

14. Li D, Xu X, Liu J, Wu P. The relationship between life event

and pregnancy stress: the mediating effect of mental health

and the moderating effect of husband support [in Chinese].

J Psychol Sci 2013;36:876-83.

15. Dennis CL, Ross L. Women’s perceptions of partner

support and conflict in the development of postpartum

depressive symptoms. J Adv Nurs 2006;56:588-99. Crossref

16. Yang H, Lu Y, Ren L. A study on the impact of bearing

two children on urban youth’s work-family balance: the

empirical analysis based on the third survey of Chinese

women’s social status [in Chinese]. Popul Econ 2016;9:1-9.

17. Hu J, Wang Y. Study on related risk factors of patients with

pre-and postnatal depression [in Chinese]. Chin Nurs Res

2010;24:765-7.

18. Lee DT, Yip AS, Chan SS, Lee FF, Leung TY, Chung TK.

Determinants of postpartum depressive

symptomatology—a prospective multivariate study among

Hong Kong Chinese Women [in Chinese]. Chin Ment

Health J 2005;9:54-9.

19. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Income of villagers in poor rural areas in 2019 [in Chinese]. Available from:

http://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202001/t20200123_1767753.html. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

20. Sun J, Zhang J, Li C, Lu Y. Strategic judgements and

development suggestions on the development of poverty-stricken

areas in China [in Chinese]. Manage World

2019;35:150-9,185.

21. Peterman A, Schwab B, Roy S, Hidrobo M, Gilligan DO.

Measuring women’s decision making: indicator choice and

survey design experiments from cash and food transfer

evaluations in Ecuador, Uganda, and Yemen. World Dev

2021;141:105387. Crossref

22. Adouard F, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Golse B.

Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale

(EPDS) in a sample of women with high-risk pregnancies

in France. Arch Womens Ment Health 2005;8:89-95. Crossref

23. Zhang H, Li L. Comparative analysis of 3 postpartum depression scales abroad [in Chinese]. Chin J Nurs

2007;2:186-8.

24. Lee DT, Yip SK, Chiu HF, et al. Detecting postnatal

depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese

version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J

Psychiatry 1998;172:433-7. Crossref

25. Liu Y, Zhang L, Guo N, Li J, Jiang H. Research progress

of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in screening

of perinatal depression [in Chinese]. Chin J Mod Nurs

2021;27:5026-31.

26. Wang Y, Guo X, Lau Y, Chan KS, Yin L, Chen J.

Psychometric evaluation of the Mainland Chinese version

of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Int J Nurs

Stud 2009;46:813-23. Crossref

27. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The

multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers

Assess 1988;52:30-41. Crossref

28. Yan R, Liu L, Zhang L. Analysis of the relationship between social support self-efficacy and health behaviours

among college students [in Chinese]. Chin J Sch Health

2010;31:362-3.

29. Zhang X, Li X, Li Y, Quan X, Li X. Study on status and

influencing factors of antenatal depression among urban

women in western China [in Chinese]. Matern Child

Health Care China 2019;34:5275-7.

30. Dibaba Y, Fantahun M, Hindin MJ. The association of

unwanted pregnancy and social support with depressive

symptoms in pregnancy: evidence from rural southwestern

Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:135. Crossref

31. Wu H, Rao J. Research review on left-behind women [in Chinese]. J Chin Agric Univ Soc Sci 2009;26:18-23.

32. Hou F, Cerulli C, Wittink MN, Caine ED, Qiu P. Depression, social support and associated factors among women living

in rural China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens

Health. 2015;15:28. Crossref

33. Yue A, Gao J, Yang M, Swinnen L, Medina A, Rozelle S.

Caregiver depression and early child development: a

mixed-methods study from rural China. Front Psychol

2018;9:2500. Crossref

34. Xie RH, Yang J, Liao S, Xie H, Walker M, Wen SW. Prenatal

family support, postnatal family support and postpartum

depression. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010;50:340-5. Crossref

35. Wei Q, Zhang C, Hao B, Wang X. Study on parenting

concepts and behaviours of caregivers with children under

3 years old in rural areas of China [in Chinese]. Matern

Child Health Care China 2017;32:1759-61.

36. Hao J, Wang F, Huang J. Male labour migration, women

empowerment and household protein intake: evidence

from less developed rural areas in China [in Chinese].

China Rural Econ 2021;8:125-44.

37. Xiao G. A practical study of puerperal health care in a menstrual centre [in Chinese]. Chin J Mode Drug Appl

2016;10:271-2.