Hong Kong Med J 2023 Feb;29(1):57-65 | Epub 9 Feb 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE (HEALTHCARE IN MAINLAND CHINA)

Assessment of healthcare quality among village

clinicians in rural China: the role of internal work motivation

Q Gao, PhD; L Peng, MSc; S Song, MSc; Y Zhang, MSc; Y Shi, PhD

Center for Experimental Economics in Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi'an, China

Corresponding author: Prof Y Shi (shiyaojiang7@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: The quality of primary care is

important for health outcomes among residents

in China. There is evidence that internal work

motivation improves the quality of healthcare

provided by clinicians. However, few empirical

studies have examined the relationship between

internal work motivation and clinical performance

among village clinicians in rural China. This study

was performed to evaluate healthcare quality among

village clinicians, then explore its relationships with

internal work motivation among those clinicians.

Methods: We collected survey data using a

standardised patient method and a structured

questionnaire. We observed 225 interactions

between standardised patients and village clinicians

from 21 counties in three provinces. We used logistic

regression models to analyse the relationships

between work motivation and healthcare quality,

then conducted heterogeneity analysis.

Results: Healthcare quality among village clinicians

was generally low. There was a significantly positive

correlation between internal work motivation and healthcare quality among village clinicians (P<0.1).

Additionally, the positive effect of internal work

motivation on healthcare quality was strongest

among clinicians who received financial incentives

and had a lighter workload (fewer patients per

month) [P<0.1].

Conclusion: Healthcare quality among village

clinicians requires urgent improvement. We

recommend implementing financial incentives to

stimulate internal work motivation among village

clinicians, thus improving their clinical performance.

New knowledge added by this study

- Internal work motivation was positively correlated with healthcare quality among village clinicians in rural China.

- The positive correlation was strongest among clinicians who received financial incentives and had a lighter workload (fewer patients per month).

- Healthcare quality among village clinicians in rural China should be enhanced by improving their internal work motivation.

- Interventions that include financial incentives should be implemented to strengthen the positive effect of internal work motivation on healthcare quality among clinicians.

Introduction

Village clinics, the first tier of rural health systems

in China, are responsible for preventing and treating

common diseases among rural residents.1 2 However,

the quality of healthcare provided by village clinicians

may be unsatisfactory in rural China.3 4 Village

clinicians generally have a low level of education

and limited medical qualifications.4 There is some

evidence that, among village clinicians, the first

records of formal schooling are primarily vocational

school degrees; most (84.3%) of these clinicians only have the basic medical certification necessary to

practise medicine in rural areas.5 Moreover, despite

limited empirical evaluation, available data indicate

that rural primary clinicians have low diagnostic

quality and provide poor management of chronic

diseases.6 A 2012 study in Shaanxi Province revealed

that 41% of diagnoses were incorrect; treatments

were considered correct or partially correct in 53%

of clinician-patient interactions.5 A systematic

review of 24 studies between 2000 and 2012 showed

the rate of antibiotic use in rural clinics was much higher than the rate recommended by the World Health Organization.7 8

The Chinese Government has recognised

the need to strengthen primary healthcare in rural

areas. To improve health among rural residents, the

government has recently issued multiple policies

that are intended to improve service capacity within

primary medical systems.9 10 For example, to improve

clinical knowledge among village clinicians, several

government departments jointly implemented a plan

in 2013, which focused on the provision of continuing

education for clinicians.11 In 2019, the Basic Medical

and Health Promotion Law of the People’s Republic

of China emphasised the need to support the

development of primary medical institutions and

implement various policies that would improve

primary medical service capabilities.12

Although improvements in internal work

motivation among village clinicians may help to

enhance their medical performance, few empirical

studies have examined the relationship between

these two characteristics among village clinicians

in rural China. Theory-focused researches indicate

that internal work motivation is important for

improvements to clinician performance.13 14 Other

theory-based researches in China have suggested that

clinicians with higher internal motivation are more

likely to deliver higher-quality work.15 16 Quantitative

analyses of clinician behaviour, primarily conducted

in other countries, have also revealed positive effects

of internal work motivation on healthcare quality

and work performance of clinicians.17 18 19 To our

knowledge, empirical studies of work motivation in China have primarily focused on individuals in

business careers and similar occupations; few have

considered groups of clinicians.20 21 22 Thus, there

have been few empirical studies involving village

clinicians in rural China.

This study explored the relationship between

internal work motivation and healthcare quality

among village clinicians in rural China. First, using

a standardised patient method and questionnaire

interviews, we evaluated healthcare quality and

internal work motivation among village clinicians.

Second, we examined the relationships between

internal work motivation and healthcare quality

among village clinicians. Third, we conducted

heterogeneity analysis with a focus on clinician

workload and financial incentives.

Methods

Sampling and data collection

Our study sampling was conducted in the rural

areas of three prefectures, each located in one of

the following three provinces: Sichuan, Shaanxi, and

Anhui. Representative samples were selected using a

multi-level random method. First, 21 sample counties

were randomly selected from the sample prefectures.

Next, 10 townships from each sampled county were

randomly chosen as sample townships; 209 sample

townships were selected because one sample county

contained only nine townships. Then, one village

was randomly selected from each township. Finally,

all village clinics in the sample village were included;

one standardised patient interaction was completed

in the sample village.

We conducted two sets of surveys to collect

data regarding basic characteristics, internal

work motivation, and healthcare quality among

village clinicians in 2015. In the first set of surveys,

we primarily gathered information regarding

the characteristics of village clinics and village

clinicians. Specifically, we used a facility structured

questionnaire to enquire about the value of each

sample clinic’s medical instruments and institutional

net income in 2014 (both in Renminbi [RMB]), and

length of daily lunch break (hours). We recorded

the following characteristics of sample village

clinicians: age, gender, level of education and clinical

qualifications, duration of service, monthly salary

(in RMB), number of training days in 2014, clinician

workload (mean number of patients per month),

mean duration of consultation per patient (minutes),

and any financial incentives. Additionally, we asked

village clinicians to respond to questions regarding

internal work motivation.

In the second set of surveys, we used a

standardised patient method to evaluate the

quality of healthcare provided by sample village

clinicians. This method avoids problems such as

the Hawthorne effect and recall bias, accurately assesses healthcare quality among clinicians, and

is widely used in other countries.23 24 We recruited

63 individuals (ie, standardised patients; 21 in each

province) to present three predetermined disease

cases of diarrhoea, tuberculosis, and unstable angina

in a standardised manner. Generally, we randomly

allocated one standardised patient to each sample

clinic to report a case that had been randomly

selected prior to allocation.

Measurement of healthcare quality

We evaluated the quality of healthcare provided

by village clinicians using three indicators: process

quality, diagnostic accuracy, and treatment accuracy.

We assigned a process quality value of 1 to clinicians

who completed more than the mean percentage of

suggested items, indicating a high-quality enquiry

process. Otherwise, the process quality value was 0.

Regarding diagnostic and treatment accuracies, we

assigned a value of 0 to an ‘incorrect’ result, based

on predetermined criteria. Otherwise, ‘correct’ or

‘partly correct’ results were assigned an accuracy

value of 1. The treatment was also considered correct

if the clinician referred the patient to a higher-level

hospital.

Measurement of internal work motivation

According to Amabile and Mueller,25 an individual’s

work motivation is defined as internal work

motivation if it originates from love and interest. The

internal motivation instrument in our study included

four items, such as ‘because I like what I do for a living'.

The responses of four items were rated on a 7-point

Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree

to 7 = strongly agree. In this study, we assigned a

value of 0 to responses indicating disagreement or

neutrality (with original score of 1-4) and a value of

1 to responses indicating agreement (with original

score of 5-7). The total score of the four items on our

instrument represented a clinician's level of internal

work motivation. The total score ranges from 0 to 4;

a higher score indicated a higher level of motivation.

The Cronbach’s α value of the internal work

motivation questionnaire was 0.826, which indicated

that the scale had good internal consistency. The

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value of the questionnaire

was 0.705, indicating that the scale had good

structural validity. These results confirmed that the

questionnaire was an acceptable measurement tool.

Statistical analysis

STATA15.0 software (Stata Corporation; College

Station [TX], United States) was used to perform

descriptive and regression analyses of the collected

data. Logistic regression models with a significance

threshold of P<0.1 were used to analyse relationships

between internal work motivation and healthcare

quality.26 27 28 Two items, clinician workload × internal motivation interaction and financial incentive ×

internal motivation interaction, were added to the

model for analyses of heterogeneity. All regression

analyses were adjusted for fixed effects of disease

cases, standardised patients, and the coder.

Results

Characteristics of sample village clinicians

and clinics

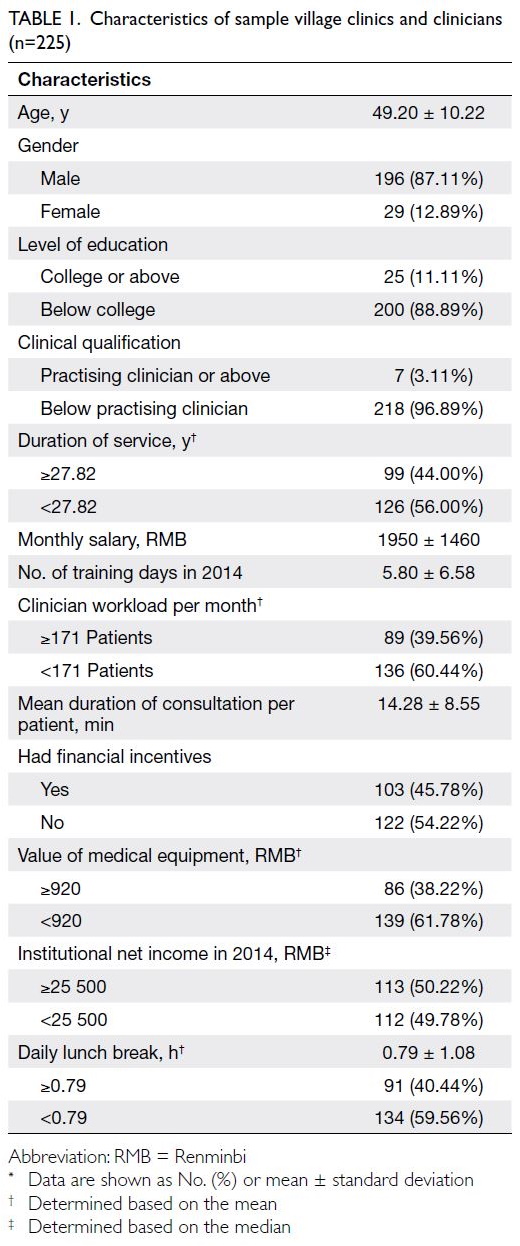

In total, 225 village clinicians from 225 village clinics were included in this study. Table 1 describes the

basic characteristics of sample village clinicians.

The mean age of the clinicians was 49.20 years, and

196 clinicians (87.11%) were men. Among the 225

clinicians, 25 (11.11%) had attended college or above,

whereas seven (3.11%) had a practising clinician

qualification. Each clinician examined a mean of

171 patients per month. Mean salaries for village

clinicians were particularly low (slightly >1900 RMB

per month), and 103 clinicians (45.78%) had received

financial incentives.

Table 1 also describes the characteristics of

sample village clinics. The mean value of medical

equipment was 920 RMB, and the mean institutional

net income in 2014 was 25 500 RMB. However, only

86 clinics (38.22%) had a medical equipment value

above the mean. This result indicates that the value of medical equipment considerably varied among

sample clinics, and the value of medical equipment

in most clinics was inadequate. Notably, clinics had

a mean lunch break length of <1 hour.

Healthcare quality among village clinicians

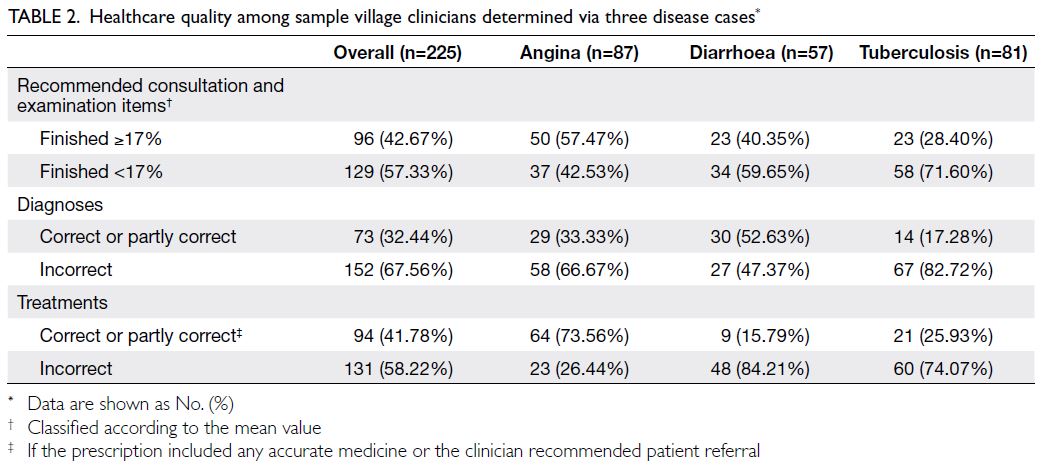

The unannounced standardised patients completed

225 disease cases (57, 87, and 81 cases of diarrhoea,

angina, and tuberculosis, respectively). Table 2

shows the healthcare quality among sample village

clinicians determined via three disease cases.

On average, the clinicians completed 17% of the

recommended consultation and examination items.

Furthermore, 129 clinicians (57.33%) completed

fewer than the mean number of recommended

consultation and examination items. Among all types

of cases, 73 clinicians (32.44%) provided a completely

or partially correct diagnosis. Furthermore, 94

clinicians (41.78%) provided correct or partly correct

treatments across all types of cases. Although the

results of these three indicators varied among

diseases, the percentages of clinicians with number

of recommended consultation and examination

items above the mean, number of correct diagnoses,

and number of treatments for each disease were

generally low.

Internal work motivation of village clinicians

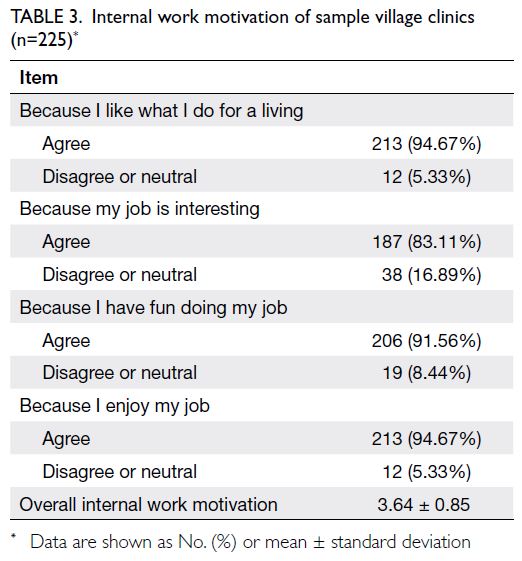

Table 3 shows the levels of internal work motivation

among sample village clinicians. Overall, 213

clinicians (94.67%) believed that ‘I like what I do for

a living’ or ‘I enjoy my job’ motivated their work in

clinics. Furthermore, 187 (83.11%) and 206 (91.56%)

clinicians indicated that their respective main work

motivations were ‘because my job is interesting’ and

‘because my job is fun’. Integration of the scores for

the four items revealed that the mean overall score for

internal work motivation was 3.64 ± 0.85 (range, 0-4).

Relationships between internal work

motivation and healthcare quality among village clinicians

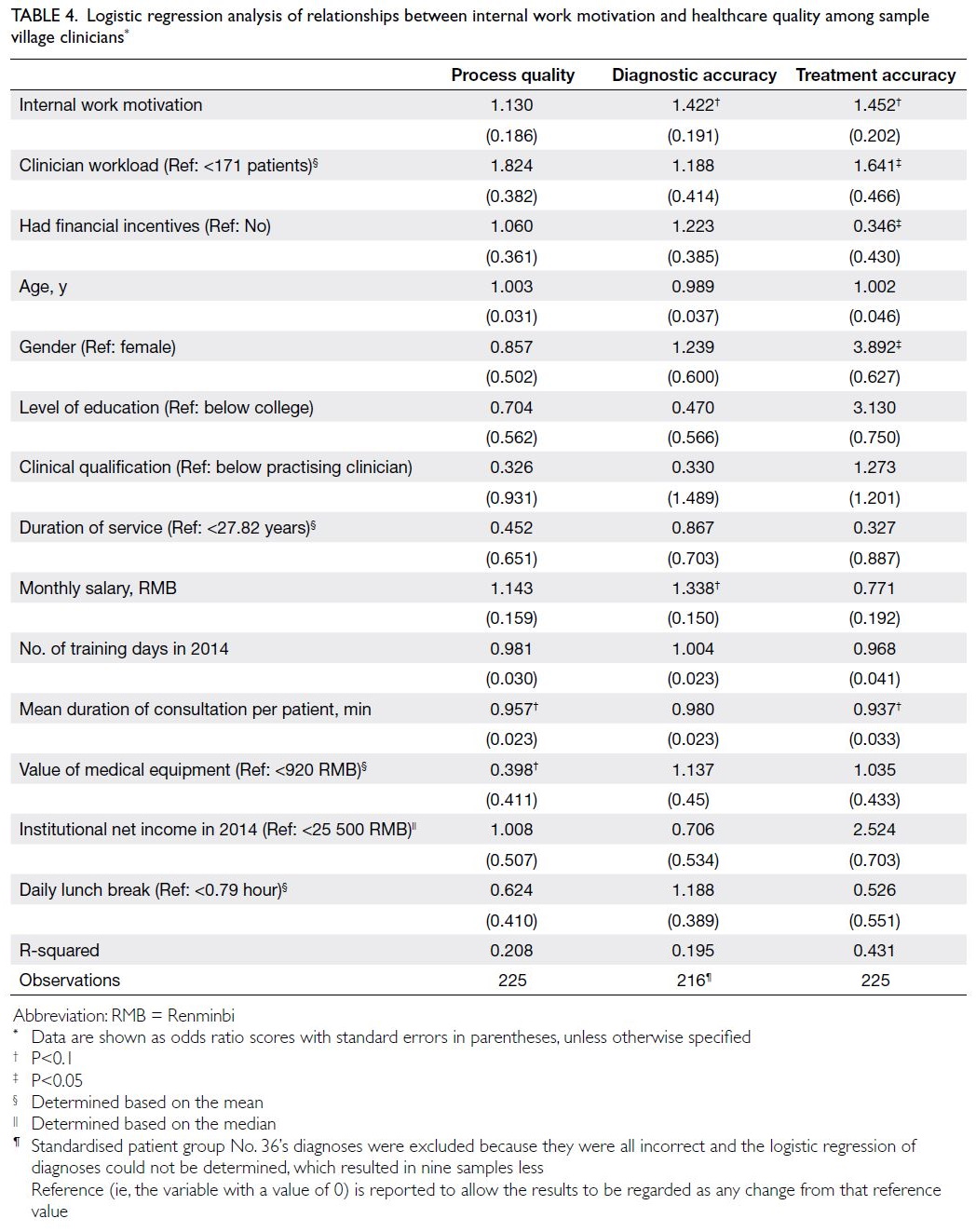

Table 4 presents the results of logistic regression

analysis of the relationship between internal work

motivation and healthcare quality among village

clinicians. Internal work motivation had a positive

effect on clinical performance among sample clinicians. Specifically, for each one-unit increase

in internal work motivation, village clinicians were

42.17% (P<0.1) and 45.61% (P<0.1) more likely to

provide a correct or partially correct diagnosis and

treatment, respectively.

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of relationships between internal work motivation and healthcare quality among sample village clinicians

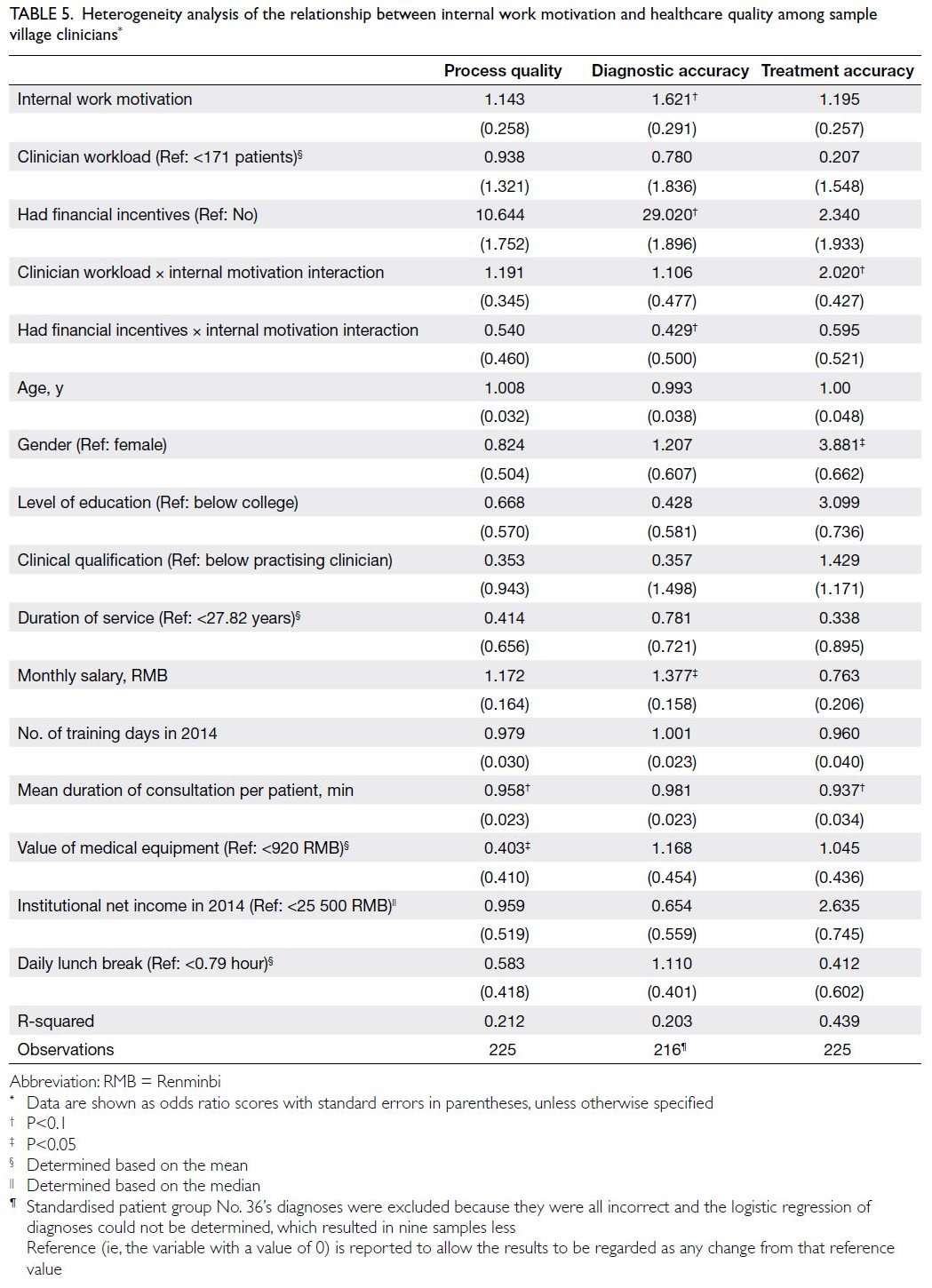

Table 5 shows the results of heterogeneity

analysis from the perspective of clinician workload

and financial incentives. The clinician workload × internal motivation interaction was significantly

negatively correlated with diagnostic accuracy,

whereas the financial incentive × internal motivation

interaction was significantly positively correlated with treatment accuracy (P<0.1). These results

indicate that a heavier workload could hinder the

positive effect of internal motivation on diagnostic

accuracy among village clinicians. Furthermore, among village clinicians who received financial

incentives, the positive effect of their internal work

motivation on their treatments was stronger than

the corresponding effect among village clinicians

who did not receive financial incentives.

Table 5. Heterogeneity analysis of the relationship between internal work motivation and healthcare quality among sample village clinicians

Discussion

This study evaluated the healthcare quality among village clinicians in rural China and its relationship

with internal work motivation among these

clinicians, through an analysis of 225 rural village

clinicians from three provinces in 2015. There were

three main findings. First, healthcare quality among

village clinicians needed to be improved. Second,

village clinicians with stronger internal work

motivation were more likely to offer appropriate

treatment. Third, village clinicians with a lighter

workload (fewer patients per month) or financial

incentives exhibited a stronger positive correlation

between internal motivation and healthcare quality.

Generally, interactions between unannounced

standardised patients and sample village clinicians

showed that poor healthcare quality was provided

by village clinics in rural China. On average, village

clinicians completed only 17% of the recommended

consultation and examination items. The rates

of diagnostic accuracy and treatment accuracy

(including correct or partly correct treatment)

were 32.44% and 41.78%, respectively. Our findings

of poor healthcare quality are comparable with

the results of other studies performed at primary

health centres in rural China. For example, a study

based on the patient’s perspective, conducted in

Guangdong Province, highlighted the difficulty in

maintaining adequate coordination among primary

medical services.29 A survey using a standardised

patient method revealed that healthcare quality was

worse in rural China than in primary care settings

in Nairobi, Kenya.30 A systematic analysis of rural

township health centres in Shandong Province also

indicated a need for improved healthcare quality

among primary care clinicians.16

We found that internal work motivation was

generally high among village clinicians. The mean

internal work motivation score was 3.64 ± 0.85,

indicating that most village clinicians liked their jobs

and were interested in their careers. Consistent with

our findings, previous studies in other countries

showed that most medical workers had high levels

of internal work motivation.31 32 33 Although few

empirical studies have evaluated internal work

motivation among village clinicians, there is some

evidence that rural primary care clinicians in China

experience meaning and pleasure from engaging in

medical work.13 Additionally, similar to results in

other countries, we found that among the intrinsic

factors, most village clinicians believed that a love

for their career motivated them to work.33 34 35

Consistent with data from studies in other

countries,17 19 our empirical analysis demonstrated

significant positive correlations between internal

work motivation and healthcare quality among

village clinicians in rural China. According to affect

heuristic theory, this relationship presumably arises

because individuals rely on emotions to make

behavioural decisions, and a positive attitude will

lead to higher-quality behaviours.36 Empirical results

from other countries support this assumption.

A study in the United States demonstrated the

importance of internal work motivation in medical

behaviour decisions; clinicians with higher internal

motivation were more willing to maintain higher

quality in their work.17 The findings of studies in

developing countries, such as Ghana and Indonesia,

also indicated that work motivation can significantly

improve the quality of medical services provided

by clinicians.19 37 Thus, efforts to stimulate internal

work motivation among village clinicians may help

to improve their healthcare quality.

The results of heterogeneity analysis showed

that the positive effect of internal work motivation

on healthcare quality varied according to clinician

workload and financial incentives. Specifically,

internal work motivation had a stronger positive

effect on clinical performance among village

clinicians who had a lighter workload (fewer patients

per month). This is presumably because clinicians

with a heavier workload (more patients) are more

likely to experience burnout38 and a decreased

sense of autonomy,39 40 which could reduce internal

motivation and ultimately lead to a decline in work

performance.14 39 41 Additionally, compared with

village clinicians who did not receive financial

incentives, clinicians who received financial incentives

experienced a stronger positive effect on healthcare

quality because of their internal work motivation.

Studies of clinicians, combined with the results of

theoretical analyses in other fields (ie, motivational

synergy theory and self-decision theory), suggest

that the provision of financial incentives encourages

a belief of greater competence among clinicians; this

belief, in conjunction with internal work motivation,

enables clinicians to maintain high quality in their

work.13 14 41 42 Previous empirical studies have also demonstrated that performance-related financial

incentives can improve internal work motivation

among employees, leading to improvements in

performance.43

The results of these heterogeneity analyses

support efforts to enhance the positive effect of

internal work motivation on healthcare quality

by providing appropriate incentives for clinicians.

Consistent with this perspective, the Chinese

Government has been implementing incentive

programmes during the past decade to improve

healthcare quality among primary care clinicians in rural China.10 11 For example, the government is

actively restructuring the salary and performance

system, while asserting that healthcare systems at all

levels should engage in combined efforts to provide

additional financial incentives.44

To further promote internal work motivation

among clinicians and improve their work

performance, we recommend the revision of

governmental incentives policies, based on existing

policies. Specifically, medical institutions at all levels

should establish performance accountability45; and

emphasis should be placed on including physician

performance in assessments to incentivise high-quality

healthcare. Furthermore, medical institutions

at all levels should provide additional financial

incentives to clinicians based on assessments of

patient experiences. These programmes could

strengthen the positive effect of internal motivation

on work performance among clinicians and improve

their healthcare quality. Additionally, the workload

of primary clinicians should be carefully managed

to preserve the positive effect of their intrinsic

motivation on job performance.

This study had a few limitations. First, it was

a cross-sectional study, and the results represent

correlations rather than causal relationships.

Second, because we randomly selected samples from

Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Anhui provinces, our results

may not be fully representative of village clinicians

and village clinics throughout rural China. Third, the

reported level of internal work motivation may have

been overestimated because this variable was self-reported

by village clinicians.

Conclusion

Overall, healthcare quality was poor among village

clinicians in rural China. Furthermore, there

were positive correlations between internal work

motivation and healthcare quality among rural

village clinicians; these positive correlations were

stronger among clinicians with financial incentives

and lighter workload. Our findings suggest that the

Chinese Government should implement policies to

provide financial incentives for clinicians, with the

goal of enhancing internal work motivation among

village clinicians and improving their healthcare quality.

Author contributions

Concept or design: Q Gao, Y Shi, L Peng.

Acquisition of data: L Peng, S Song, Y Zhang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: L Peng, Q Gao, S Song.

Drafting of the manuscript: L Peng, Q Gao, Y Shi.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: L Peng, S Song, Y Zhang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: L Peng, Q Gao, S Song.

Drafting of the manuscript: L Peng, Q Gao, Y Shi.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

As an International Editorial Advisory Board member of the journal, Y Shi was not involved in the peer review process.

Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

All authors thank the standardised patients and investigators for their contribution and hard work.

Funding/support

This work received funding from 111 Project (Grant No.: B16031), National Natural Science Foundation of China

(Grant No.: 72203134) and Innovation Capability Support

Program of Shaanxi, China (Grant No.: 2022KRM007).

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Sichuan University, China (Protocol No.: K2015025). The board approved the verbal consent procedure. Participants

in this study were informed of the survey procedure and

consented to publication.

References

1. Babiarz KS, Miller G, Yi H, Zhang L, Rozelle S. China’s

new cooperative medical scheme improved finances of

township health centers but not the number of patients

served. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1065-74. Crossref

2. Shi Y, Xue H, Wang H, Sylvia S, Medina A, Rozelle S.

Measuring the quality of doctors’ health care in rural

China: an empirical research using standardized patients

[in Chinese]. Stud Labour Econ 2016;4:48-71.

3. Guo W, Sylvia S, Umble K, Chen Y, Zhang X, Yi H. The

competence of village clinicians in the diagnosis and

treatment of heart disease in rural China: a nationally

representative assessment. Lancet Reg Health West Pac

2020;2:100026. Crossref

4. Tan J, Yao Y, Wang Q. Comparative analysis of the

development and service utilisation of health resources

in Guangxi township hospitals and the whole country [in

Chinese]. Soft Sci Health 2019;33:46-50.

5. Sylvia S, Shi Y, Xue H, et al. Survey using incognito

standardized patients shows poor quality care in China’s

rural clinics. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:322-33. Crossref

6. Li X, Lu J, Hu S, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet 2017;390:2584-94. Crossref

7. Yin X, Song F, Gong Y, et al. A systematic review of antibiotic utilization in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68:2445-52. Crossref

8. Virtual Health Library. Using indicators to measure

country pharmaceutical situations: fact book on WHO

level I and level II monitoring indicators. 2006. Available

from: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/mis-19254. Accessed 30 Sep 2021.

9. Communist Party of China Central Committee, State

Council, People’s Republic of China. “Healthy China 2030”

Programme [in Chinese]. 2016. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm.

Accessed 30 Sep 2021.

10. State Council, People’s Republic of China. “Thirteenth

Five-Year” Sanitation and Health Plan [in Chinese]. 2017.

Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-01/10/content_5158488.htm. Accessed 30 Sep 2021.

11. National Health and Family Planning Commission, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Ministry

of Finance of the People’s Republic of China, National

Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. National

Rural Doctor Education Plan (2011-2020) [in Chinese].

2013. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2013-10/30/content_2518099.htm. Accessed 20 Jan 2023.

12. State Council, People’s Republic of China. The 15th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People’s Congress. Basic Medical Hygiene and Health Promotion

Law of the People’s Republic of China [in Chinese]. 2019.

Available from: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-12/29/content_5464861.htm. Accessed 5 Oct 2021.

13. Yuan B, Meng Q. Behaviour determinants of rural health workers: based on work motivation theory analysis [in Chinese]. Chin Health Econ 2012;31:50-2.

14. Kao AC. Driven to care: aligning external motivators with intrinsic motivation. Health Serv Res 2015;50 Suppl 2:2216-22. Crossref

15. Yuan B, Meng Q, Hou Z, Sun X, Song K. Analysis on incentive mechanism and motivation of rural health

providers [in Chinese]. Chin J Health Policy 2010;3:3-9.

16. Yuan S, Meng Q, Sun X. Studying on the quality of medical services in township health centres in view of

structural quality [in Chinese]. Chin Health Serv Manage

2012;29:841-4.

17. Green EP. Payment systems in the healthcare industry: an experimental study of physician incentives. J Econ Behav Organ 2014;106:367-78. Crossref

18. Mangkunegara AP, Agustine R. Effect of training, motivation and work environment on physicians’

performance. Acad J Interdiscip Stud 2016;5:173-88. Crossref

19. Al Aluf W, Sudarsih S, Musemedi DP, Supriyadi S. Assessing the impact of motivation, job satisfaction,

and work environment on the employee performance in

healthcare services. Int J Sci Technol Res 2017;6:337-41.

20. Hou X, Lu F. Effects of work values of millennial employees,

intrinsic motivation on job performance: the moderating

effect of organizational culture. Manage Rev 2018;30:157-68.

21. Li W, Mei J. Intrinsic motivation and employee performance: based on the effects of work engagement as

intermediary [in Chinese]. Manage Rev 2013;25:160-7.

22. Liao J, Jing Z, Liu W, Wang X. Promotion opportunity

stagnation and job performance: the mediating—role of

intrinsic motivation and perceived insider status. Ind Eng

Manage 2015;20:15-21.

23. Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B. In

urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed

low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps.

Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2774-84. Crossref

24. Rethans JJ, Gorter S, Bokken L, Morrison L. Unannounced

standardised patients in real practice: a systematic

literature review. Med Educ 2007;41:537-49. Crossref

25. Amabile TM, Mueller J. Studying creativity, its processes,

and its antecedents: an exploration of the componential

theory of creativity. In: Zhou J, Shalley CE, editors.

Handbook of Organizational Creativity. New York:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008: 33-64.

26. Lee KI, Koval JJ. Determination of the best significance

level in forward step-wise logistic regression. Commun

Stat Simul Comput 1997;2:559-75. Crossref

27. Maneejuk P, Yamaka W. Significance test for linear

regression: how to test without P-values? J Appl Stat 2020;31:827-45. Crossref

28. Feise R. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med Res Methodol 2002;17:1471-2288-2-8. Crossref

29. Feng S. Analysis of the quality of primary care and the

influencing factors in rural Guangdong Province—based

on demander perspective [in Chinese]. Chin Health Serv Manage 2016;33:824-7.

30. Daniels B, Dolinger A, Bedoya G, et al. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: a pilot, cross-sectional study with international comparisons. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000333.

31. Settineri S, Merlo EM, Frisone F, et al. The experience of health and suffering in the medical profession. Mediterr J Clin Psychol 2018;6:1-14.

32. Toode K, Routasalo P, Helminen M, Suominen T. Hospital

nurses’ individual priorities, internal psychological states

and work motivation. Int Nurs Rev 2014;61:361-70. Crossref

33. Tsounis A, Sarafis P, Bamidis PD. Motivation among

physicians in Greek public health-care sector. Br J Med

Med Res 2014;4:1094-105. Crossref

34. Ferraro T, dos Santos NR, Moreira JM, Pais L. Decent

work, work motivation, work engagement and burnout in

physicians. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 2020;5:13-35. Crossref

35. Lochner L, Wieser H, Mischo-Kelling M. A qualitative

study of the intrinsic motivation of physicians and other

health professionals to teach. Int J Med Educ 2012;3:209-15. Crossref

36. Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. The affect heuristic. Eur J Oper Res 2007;177:1333-52. Crossref

37. Alhassan RK, Spieker N, van Ostenberg P, Ogink A,

Nketiah-Amponsah E, de Wit TF. Association between

health worker motivation and healthcare quality efforts in

Ghana. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:37. Crossref

38. Ward ZD, Morgan ZJ, Peterson LE. Family physician burnout does not differ with rurality. J Rural Health

2021;37:755-61. Crossref

39. Wang Y, Hu XJ, Wang HH, et al. Follow-up care delivery in community-based hypertension and type 2 diabetes management: a multi-centre, survey study among rural primary care physicians in China. BMC Fam Pract 2021;22:224. Crossref

40. Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Work hours and caseload as predictors of physician burnout: the mediating effects by perceived workload and by autonomy. Appl Psychol 2010;59:539-65. Crossref

41. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Springer;

1985. Crossref

42. Amabile TM. Motivational synergy: toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in

the workplace. Hum Resour Manage Rev 1993;3:185-201. Crossref

43. Eisenberger R, Aselage J. Incremental effects of reward on experienced performance pressure: positive outcomes for intrinsic interest and creativity. J Organiz Behav

2009;30:95-117. Crossref

44. Qin J, Li S, Lin C. Reform progress and development strategy of incentive mechanism for training and use of

general practitioners in China [in Chinese]. Chin Gen

Pract 2020;23:2351-8.

45. Li X, Krumholz HM, Yip W, et al. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. Lancet 2020;395:1802-12. Crossref