Dental luxation and avulsion injuries in Hong Kong primary school children

Hong Kong Med J 2015 Aug;21(4):339–44 | Epub 17 Jul 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144433

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dental luxation and avulsion injuries in Hong Kong primary school children

SY Cho, MDS (Otago), FHKAM (Dental Surgery)

MacLehose Dental Centre, G/F, 286 Queen’s Road East, Wanchai, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SY Cho (rony_cho@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To identify the major causes and types

of dental luxation and avulsion injuries, and their

associated factors in primary school children in

Hong Kong.

Design: Case series.

Setting: School dental clinic, New Territories, Hong Kong.

Patients: The dental records of children with a

history of dental luxation and/or avulsion injury

between November 2005 and October 2012 were

reviewed. Objective clinical and radiographical

findings at the time of injury and at follow-up

examinations were recorded using a standardised

form. Data analysis was carried out using the Chi

squared test and multinomial logistic regression.

Results: A total of 220 children with 355 teeth of

dental luxation or avulsion injury were recorded.

Their age ranged from 6 to 14 years and the female-to-male ratio was 1:1.8. The peak occurrence was

at the age of 9 years. Subluxation was the most

common type of injury, followed by concussion.

Maxillary central incisors were the most commonly

affected teeth. The predominant cause was fall and

most injuries occurred at school. Incisor relationship

was registered in 199 cases: most of them were Class

I. Comparison of the incisor relationship in study

children and the general Chinese population in

another study revealed a higher proportion of Class II

and fewer Class III occlusions in the trauma group

(P<0.0001).

Conclusion: Most dental luxation and avulsion

injuries in Hong Kong primary school children are

caused by fall. Boys are more commonly affected

than girls, and a Class II incisor relationship is a

significant risk factor.

New knowledge added by this study

- This is the first epidemiological study of traumatic dental injury in children residing in Hong Kong. The present findings provide an important baseline for future comparison.

- As most injuries occur at school, it may be beneficial to educate primary school teachers about emergency care of children with dental trauma.

Introduction

Childhood injury is a major cause of death and

disability in many countries, including Hong

Kong.1 Although previous studies have reviewed

general childhood injuries in Hong Kong children,1 2 dental injuries have not been specifically studied

and reported. The oral region comprises 1% of the

total body area, yet a population-based study in

Sweden showed that it accounts for 5% of all body

injuries at all ages.3 A recent study conducted by

the Department of Health showed that injuries to

orofacial areas accounted for 1.7% of all body injuries

in children aged 14 years or below.1

Dental luxation and avulsion injuries account

for 15% to 61% of all dental traumas to permanent

teeth.4 It is an important public health concern as the

treatment of such injuries is often complicated and

requires specialist care.5 6 It also tends to occur at a young age during which growth and development

take place and so long-term follow-up is needed.5 6 7

The average number of dental visits because of

trauma to a permanent tooth during 1 year has been

shown to be much higher than that required for a

bodily injury.6 Information on how and where dental

trauma occurs, and the associated risk factors are

important data that can be used to plan a preventive

strategy. There is, however, little information about

the epidemiology of dental trauma in children

residing in Hong Kong. The aims of this retrospective

study were to identify the major causes and types

of dental luxation and avulsion injuries, and their

associated factors in primary school children

attending a school dental clinic in Hong Kong.

Methods

This retrospective study was carried out at Fanling

School Dental Clinic that provides care for

approximately 30 000 primary school children in the

Hong Kong New Territories East region. The study

materials comprised dental records of patients with

a history of dental luxation and/or avulsion injury

between November 2005 and October 2012. All

dental luxation and avulsion injuries were logged

in the electronic records using specific codes: an

electronic search of records was performed using

the same dental condition codes (DC=concussion,

DS=subluxation, DE=extrusion, DN=intrusion,

DL=lateral luxation, and DA=avulsion). All cases

were examined clinically by at least one of the three

attending paediatric dentists at the clinic who were

experienced in treating children with dental trauma.

All records were reviewed by one single examiner,

the paediatric dentist in-charge of the clinic.

Information was recorded in Microsoft Excel and

data analysis was carried out using the Chi squared

test and multinomial logistic regression with PASW

Statistics 18 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US). The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

To evaluate intra-examiner reliability, all selected

records were reviewed by the same author 1 month

after the original analysis and the findings of the two

examinations compared for discrepancies.

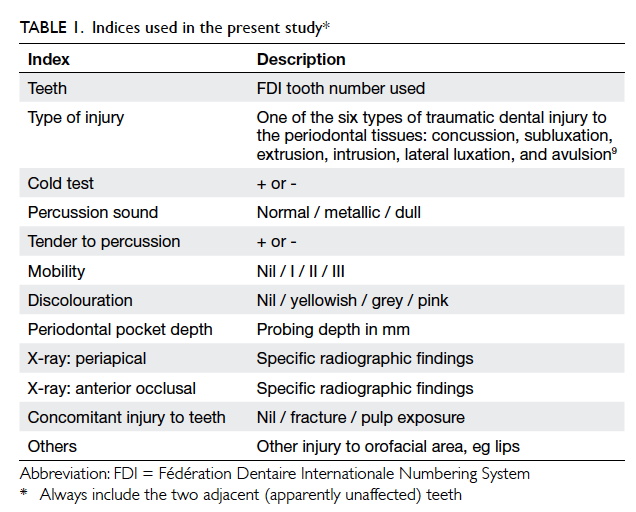

Clinical examinations

Since November 2005, a standardised dental trauma

form has been used in the clinic to facilitate follow-up

care. The following parameters

were recorded for patients who presented with

dental luxation or avulsion injuries: date and time

of injury, place where the injury occurred, cause

of trauma, presence of other orofacial soft tissue

injury, and the incisor relationship according to the

British Standard Incisor Classification.8 The type

of injury was classified according to the Andreasen

modification of the World Health Organization

classification,9 and included six types of injury to

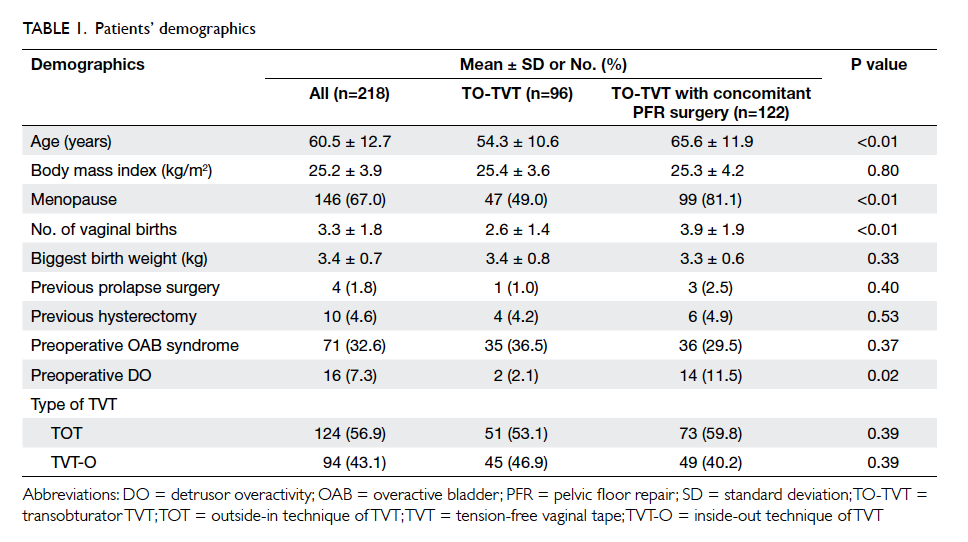

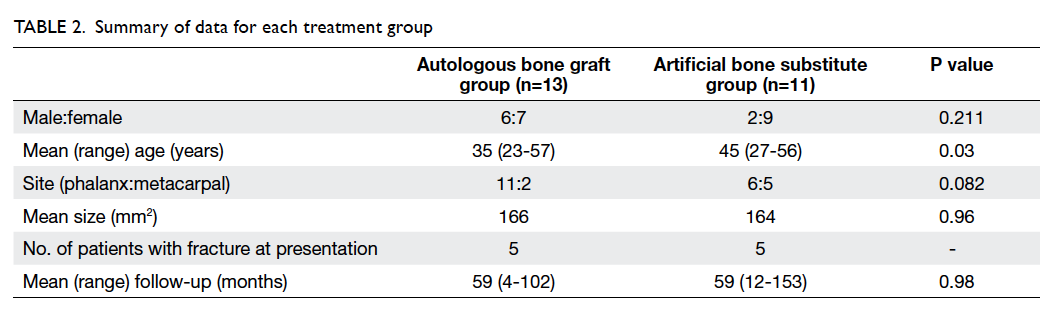

periodontal tissues (Table 1).

The adjacent apparently unaffected teeth on

both sides were also included in the examination.

For each tooth, objective clinical findings from the

initial and follow-up examinations were recorded

using the same standardised format and included

the following: pulp sensitivity test; percussion tone;

tenderness to percussion; tooth mobility; tooth

colour; periodontal probing depths; and the presence

of concomitant crown fractures and pulp exposure.

Radiographic examinations

An anterior occlusal radiograph together with

periapical radiographs of the affected teeth were

taken at the initial examination. At each follow-up

appointment, periapical radiographs were repeated

for the affected teeth. All periapical radiographs

were taken using a standard film holder (Dentsply

Rinn, Elgin [IL], US).

Follow-up examinations

All cases were followed up at regular intervals: 3

weeks, 6 to 8 weeks, 6 months, and then annually from

the time of injury. Patients with dental avulsion were

also seen on days 7 to 10 for splint removal and root

canal treatment if indicated.

Results

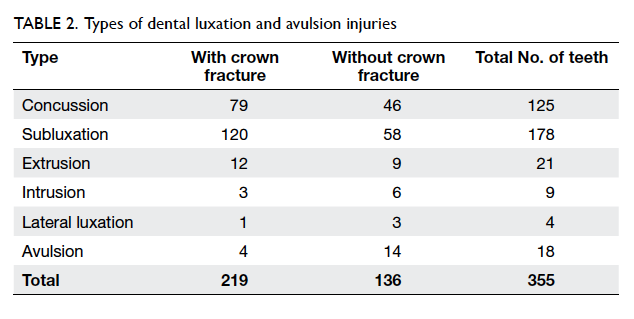

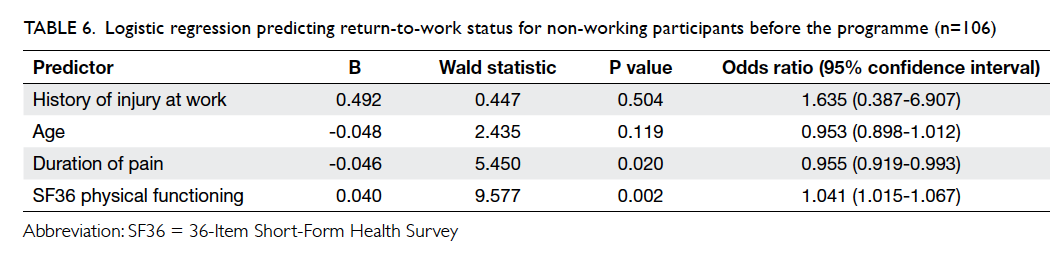

A total of 220 children with 355 teeth of dental

luxation or avulsion injury were recorded during the

study period. Their ages ranged from 6 to 14 years

(mean age, 9.2 years; standard deviation, 1.7 years). To

assess whether age was an important factor, children

were divided into two age-groups: 58% (n=128) were

aged 6 to 9 years and 42% (n=92) were 10 to 14 years at

the time of injury. The male-to-female ratio was 1.8:1,

with 141 boys and 79 girls. The gender difference in

prevalence was more prominent in children aged 9

years or above. The peak occurrence was seen at the

age of 9 years (n=46), followed by the age of 8 years

(n=44) and 10 years (n=38). Only one tooth was

traumatised in 117 (53%) children. The predominant

traumatic dental injury was subluxation, followed

by concussion (Table 2). Over 65% of teeth with

concussion or subluxation also had crown fractures.

Maxillary central incisors (295 teeth) were the most

commonly affected, followed by maxillary lateral

incisors (38 teeth) and mandibular incisors (20

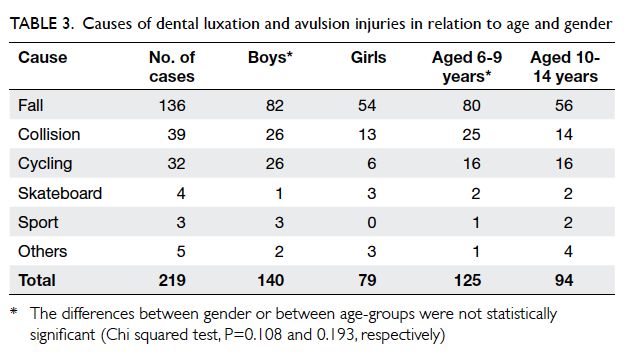

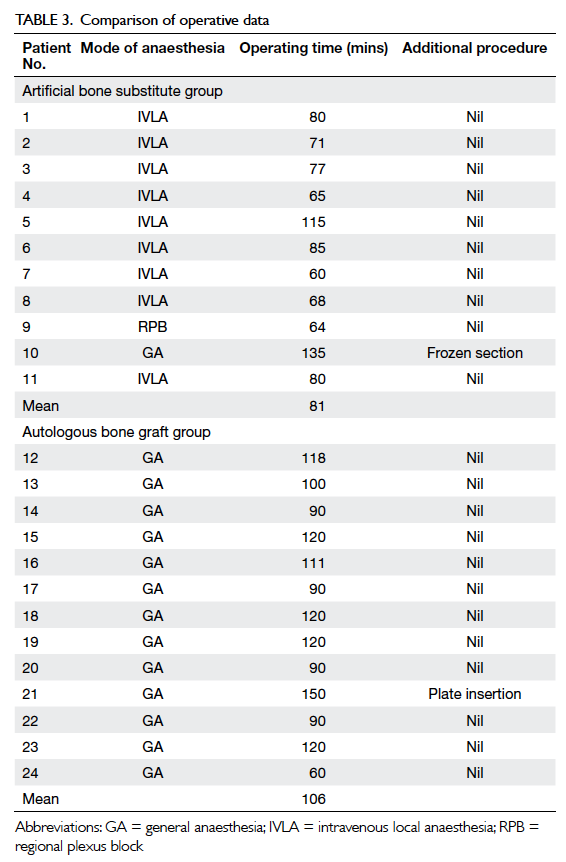

teeth). The cause of injury was recorded in 219 cases

(Table 3). Fall (62%) was the predominant cause in

both genders and age-groups, followed by collision

(18%) and cycling (15%). There were no incidents of

injury caused by motor vehicle accidents or fights.

Statistical analysis using Chi squared test showed no

significant difference in the cause of injury between

genders (P=0.108) or between the two age-groups

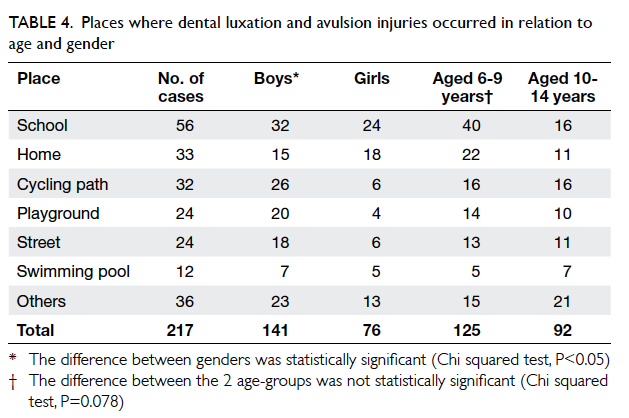

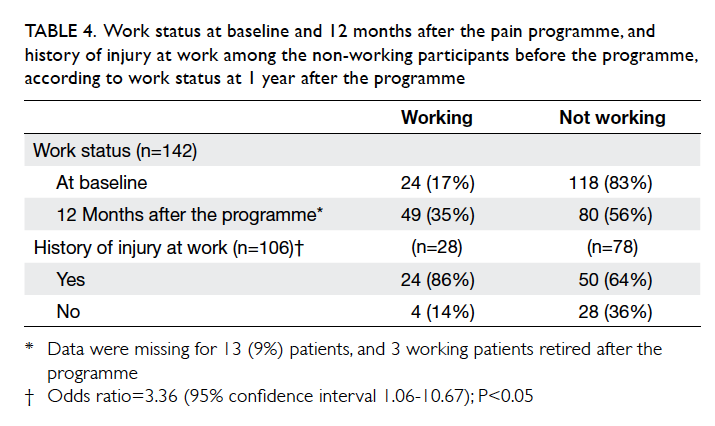

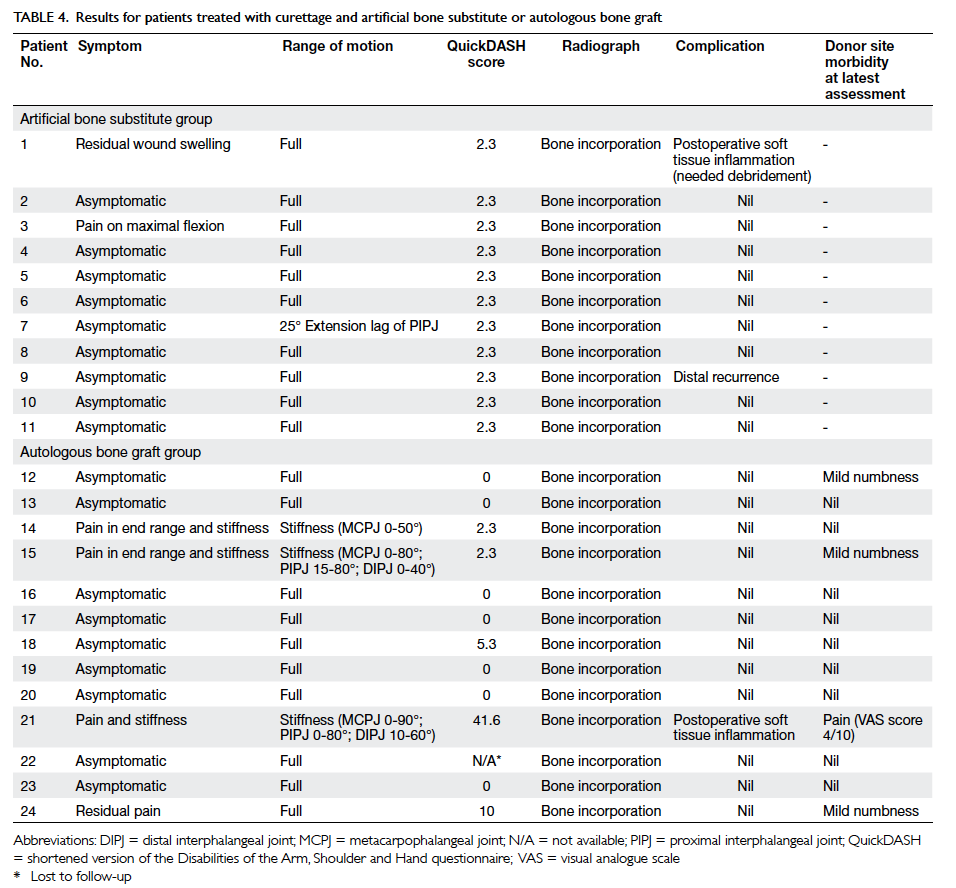

(P=0.193). The place where the injury occurred

was recorded in 217 cases: most occurred at school

(Table 4). Statistical analysis using Chi squared

test showed a significant difference in the place of

occurrence between genders (Chi squared=15.6,

degrees of freedom=6, P<0.05), but no significant

difference between the two age-groups (P=0.078).

Multivariate analysis using multinomial logistic

regression was then performed with gender and age-group

as independent variables and place of injury

as a dependent variable. Because of the relatively

small number of cases, injuries that occurred in the

playground, street, swimming pool, and other places

were grouped into one category named as other

places in the analysis. Injury occurring at school

was then compared with injuries that occurred at

home, on a cycling path, or in other places. School

was chosen as the reference because (1) it was the

most common place where injury occurred; and

(2) univariate analysis of individual places of injury

using the Fisher’s exact test showed no significant

difference between genders regarding injuries

at school whereas there were significant gender

differences in injuries that occurred at home and on

a cycling path (P<0.05). The results of the regression

showed that boys were more commonly affected than

girls (P<0.05; odds ratio [OR]=2.97; 95% confidence

interval [CI], 1.05-8.43) for injuries that occurred

on a cycling path in comparison with injuries at

school. In the same model, younger children were

significantly less commonly affected than older

children (P<0.05; OR=0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85)

for injuries that occurred in other places compared

with injuries at school.

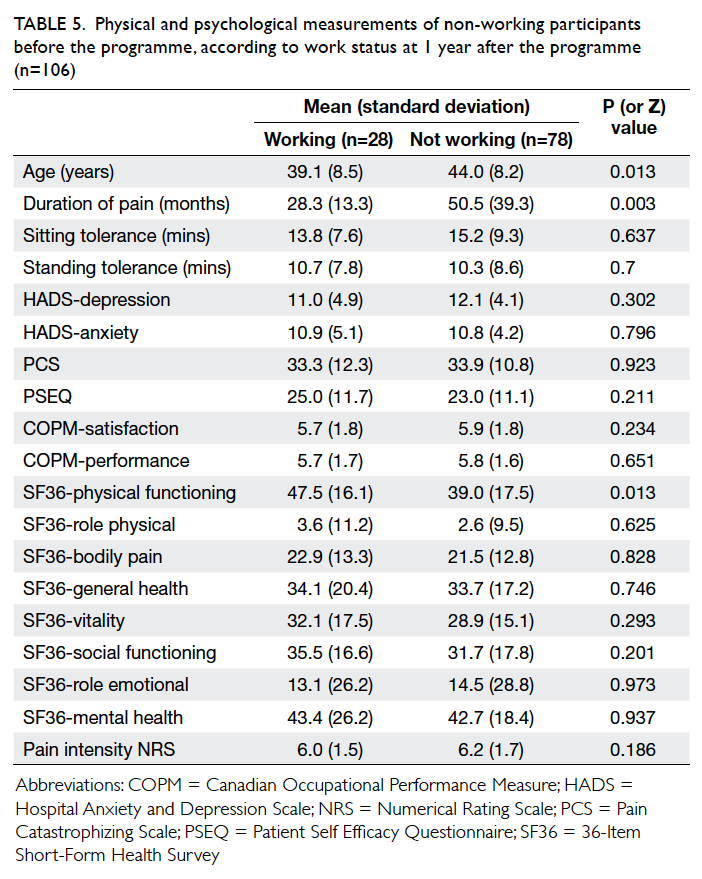

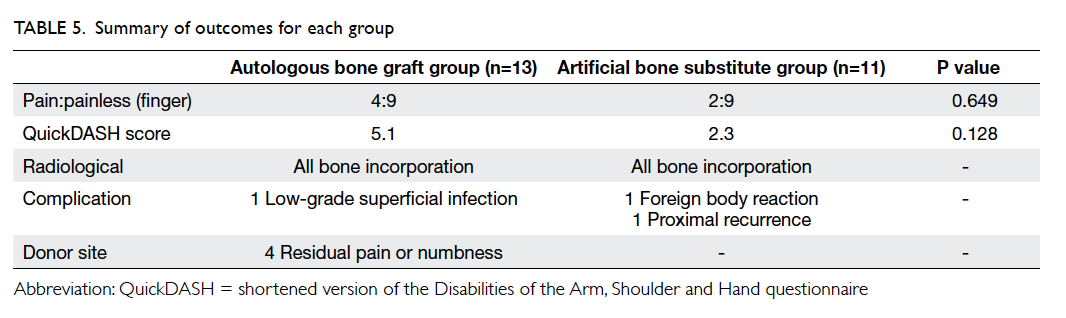

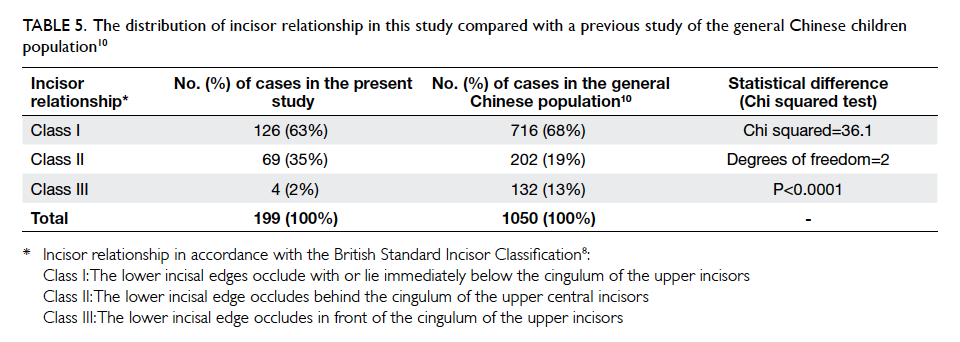

Incisor relationship was registered in 199

cases: most were Class I (63%) [Table 5]. Since such

information was not available for the whole study,

it was decided to use data from a previous study

of the general Chinese population of children as a

retrospective comparison group.10 Comparison of

these two studies showed that there was a higher proportion of Class II and fewer Class III occlusions in

the trauma group than in the general Chinese

population. Statistical analysis showed a significant

difference between the two population groups (Chi

squared=36.1, degrees of freedom=2, P<0.0001).

Soft tissue injury occurred in the orofacial region in

87 children, and lips were involved in most instances

(82%). Intra-examiner reliability was evaluated and

complete concordance of all data and parameters

was found between the two evaluations that were 1

month apart.

Table 5. The distribution of incisor relationship in this study compared with a previous study of the general Chinese children population10

Discussion

The difference in the proportion of causes of

traumatic dental injury depends on various factors

including culture, age-group, and population.11 12 In some developing countries, the most common

cause of dental injury in children is violence.9 In this

study, fall against a hard object such as the ground was the cause in over 60% of cases. This finding is

in agreement with most other studies of traumatic

dental injury in children.7 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 In a study of New

Zealand children, fall was the most common cause

in children aged 5 to 7 years, but collision became

more common in the 8- to 10-year-old group.21

Nonetheless, such a trend was not observed in this

study. Although dental injury due to cycling accidents

was not uncommon in this study, this finding may

be confounded by the fact that New Territories East

has one of the busiest cycling path networks in Hong

Kong.2 The use of helmets offers little protection

to the lower face and jaw.9 It has been suggested

that modification of the helmet design to cover the

lower face may be beneficial. There were few sports-related

injuries observed in this study. This may be

because high-risk contact sports, such as rugby and

ice hockey,5 are not very popular among Hong Kong

primary school children. Compulsory use of mouth

guards in those who participate in such activities

may also be a contributing factor. There was no case

of trauma due to a road traffic accident; this may

reflect the legal requirement in Hong Kong for all

passengers to wear a car seatbelt.

In this study more boys than girls had dental

luxation and avulsion injuries in accordance with

the findings of most other studies.7 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 24 One probable reason for the gender difference is that

boys take more risks and participate more in sports

activities. Nonetheless this gender difference has

narrowed in recent studies, possibly due to an

increased interest in sports among girls, especially

in western societies.5 11 21 In this study, a greater

gender discrepancy in frequency of dental injury

was observed in the older age-group, in accordance

with the findings of Kania et al’s study of elementary

school children in the US.24

Previous studies of dental trauma in children

have shown that most injuries occur between

the age of 6 and 12 years.7 16 17 18 The present study

population comprised primary school children

attending a regional school dental clinic. The age of

most primary school children in Hong Kong falls

within the range of 6 to 12 years, and so most of

the dental injuries for this group of children could

be registered in this study. The peak occurrence of

injury was seen in 9-year-olds, again in agreement

with previous studies where the highest frequency

of trauma to permanent dentition was observed in

9- to 10-year-olds.12 19 Nonetheless in studies from New Zealand21 and Iraq,14 the highest frequency of dental injury occurred in 5- to 7-year-olds. Glendor

et al9 observed a marked increase in the incidence

of dental injury in boys aged 8 to 10 years, with the

incidence rather stable in girls. The same trend was

also seen in this study. This may reflect the more

vigorous play characteristics of boys in this age-group

than girls.9

The majority of dental injuries involve the

anterior teeth, especially the maxillary central

incisors. The maxillary lateral and mandibular

incisors are affected less frequently.5 9 Similar findings were also observed in the present study. The

more prominent position of the maxillary central

incisors makes them more vulnerable to injury. In

addition, Kania et al24 opined that maxillary incisors

are more prone to injury than their mandibular

counterparts because of the mandible’s non-rigid

connection to the cranial base. Most of the children

in this study experienced trauma to only one tooth.

This concurs with the findings from previous

studies of dental injury in children.9 11 14 23 24 Noori and Al-Obaidi14 opined that when one tooth is

traumatised, the majority of the force is dispersed and so no more teeth will be injured.14 It has been suggested that multiple tooth injuries are seen

more often in more serious accidents such as motor

vehicle accidents and violence.8 9 24 Concussion and

subluxation together accounted for 85% of the cases

in this study, in accordance with the findings of most

previous studies on luxation and avulsion injuries

in children.7 16 17 19 21 As the force and direction of impact determines the resultant type of injury, the

findings from this study seem to suggest that most

periodontal tissue injuries in Hong Kong primary

school children are caused by more trivial incidents.9

Increased overjet and consequent incompetent lip

closure is a significant risk factor to traumatic dental

injury.7 9 13 14 15 22 23 24 In a study conducted in Iraq, 70%

of children who had a dental injury had increased

overjet.14 In many other studies, most children who

sustained a dental injury had normal overjet, yet the

percentage of children with increased overjet was

significantly higher in children with dental trauma

than in the general population.7 9

13 22 23 24 Similar

findings were also observed in the present study.

The more prominent tooth position and the lack

of a cushioning effect from the upper lip in Class

II malocclusion make the maxillary incisors more

prone to injury.14

In many previous studies, the predominant

place of injury occurrence in school-aged children

was home, followed by school and other public

places.9 13 21 22 In the present study, most injuries

occurred at school. The second and third most

common places of occurrence were home and cycling

paths, respectively. This finding was in agreement

with the population bodily injury survey of children

aged 14 years or below in Hong Kong.1 One probable

reason is that school children in Hong Kong have

relatively more play-time at school than at home. In

this study, 40% of children with a traumatic dental

injury also suffered soft tissue injury in the orofacial

region. This percentage was of similar magnitude

to another study that involved a large proportion of

children with dental luxation and avulsion injuries,17

but higher than a study with a high proportion of

minor dental trauma such as simple fracture.12 This

discrepancy may be because incidents that resulted

in dental luxation or avulsion were usually more

severe and could lead to more soft tissue damage.

One of the limitations of this study is its

retrospective design. It is, however, extremely

difficult to perform prospective trauma studies on a

population basis.25 ‘Grab’ sampling was employed in

this retrospective study, ie all patients treated in

one clinic for dental luxation and/or avulsion injury

were used in the sample. The conclusions from this

study may therefore not be applicable to other parts

of Hong Kong. To avoid inter-examiner error, all the

records were reviewed by the most senior paediatric

dentist in the clinic. The use of a standardised trauma

form helps improve the accuracy of data collected

during treatment.25 With the aid of a standardised

form, the cause of dental injury was recorded in all

but one case, and the place of trauma in all but three.

This illustrates the importance of a standardised

registry of dental traumatology.

This is the first epidemiological study of

traumatic dental injury in children resident in Hong

Kong and our data provide an important baseline

for future comparison. Very often, school teachers

are often the first to deal with an acute dental injury

and it may be beneficial to educate them about the

emergency care of children with dental trauma. For

example, with avulsion injuries, where immediate

management is critical for optimal healing, the

teachers should be taught how to replant the tooth

on site. If that could not be done, they should know

how to store the avulsed tooth in an appropriate

medium to prevent damage to the periodontal

tissue. The effects of various factors on healing will

be investigated and reported in a subsequent paper.

Dental traumas have social and economic

impacts with regard to the treatment required

but it is difficult to prevent dental injuries that are

not sports-related.6 21 One option is to improve environmental factors to prevent falling at school

and at home. Environmental and behavioural

factors, however, were not included in this study so

it is difficult to make conclusive suggestions in this

regard. Further studies are warranted.

Conclusion

The causes and types of dental luxation and avulsion

injuries in this group of Hong Kong children were

similar to those of other studies, except that more

injuries happened at school than at home. Most

dental luxation and avulsion injuries in Hong Kong

primary school children were caused by fall. Boys

were more commonly affected than girls, and Class

II incisor relationship was a significant risk factor.

Motor vehicle accident or fight was not a common

risk factor for dental injury in children. As most of

the injuries occurred at school, it may be beneficial

to educate primary school teachers about the

emergency care of children with dental trauma.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr Denise Fung for her statistical

advice in this study.

References

1. Injury survey 2008. Hong Kong: Centre for Health

Protection, Department of Health; 2010.

2. Chan CC, Cheng JC, Wong TW, et al. An international

comparison of childhood injuries in Hong Kong. Inj Prev

2000;6:20-3. Crossref

3. Petersson EE, Andersson L, Sörensen S. Traumatic oral vs

non-oral injuries. Swed Dent J 1997;21:55-68.

4. Andreasen FM, Andreasen JO. Luxation injuries of

permanent teeth: general findings. In: Textbook and color

atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth. 4th ed. Oxford:

Blackwell-Munksgaard; 2007; 372-403.

5. Glendor U. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries—a 12

year review of the literature. Dent Traumatol 2008;24:603-11. Crossref

6. Andersson L. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries.

Pediatr Dent 2013;35:102-5. Crossref

7. Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Su W, Zhou Z, Jin Y, Wang X. A

retrospective study of pediatric traumatic dental injuries in

Xi’an, China. Dent Traumatol 2014;30:211-5. Crossref

8. British standard incisor classification. Glossary of Dental

Terms BS 4492. London: British Standard Institute; 1983.

9. Glendor U, Marcenes W, Andreasen JO. Classification,

epidemiology and etiology. In: Textbook and color atlas of

traumatic injuries to the teeth. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell-Munksgaard; 2007: 217-54.

10. Lew KK, Foong WC, Loh E. Malocclusion prevalence in an

ethnic Chinese population. Aust Dent J 1993;38:442-9. Crossref

11. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Matras RC, Andreasen FM.

Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth. Part 1. An

epidemiological study of 216 intruded permanent teeth.

Dent Traumatol 2006;22:83-9. Crossref

12. Eyuboglu O, Yilmaz Y, Zehir C, Sahin H. A 6-year

investigation into types of dental trauma treated in a

paediatric dentistry clinic in Eastern Anatolia region,

Turkey. Dent Traumatol 2009;25:110-4. Crossref

13. Bendo CB, Paiva SM, Oliveira AC, et al. Prevalence and

associated factors of traumatic dental injuries in Brazilian

schoolchildren. J Public Health Dent 2010;70:313-8. Crossref

14. Noori AJ, Al-Obaidi WA. Traumatic dental injuries among

primary school children in Sulaimani city, Iraq. Dent

Traumatol 2009;25:442-6. Crossref

15. Taiwo OO, Jalo HP. Dental injuries in 12-year-old Nigerian

students. Dent Traumatol 2011;27:230-4. Crossref

16. Sandalli N, Cildir S, Guler N. Clinical investigation of

traumatic injuries in Yeditepe University, Turkey during

the last 3 years. Dent Traumatol 2005;21:188-94. Crossref

17. Díaz JA, Bustos L, Brandt AC, Fernández BE. Dental

injuries among children and adolescents aged 1-15 years

attending to public hospital in Temuco, Chile. Dent

Traumatol 2010;26:254-61. Crossref

18. Toprak ME, Tuna EB, Seymen F, Gençay K. Traumatic

dental injuries in Turkish children, Istanbul. Dent

Traumatol 2014;30:280-4. Crossref

19. Atabek D, Alaçam A, Aydintuğ I, Konakoğlu G. A

retrospective study of traumatic dental injuries. Dent

Traumatol 2014;30:154-61. Crossref

20. Hecova H, Tzigkounakis V, Merglova V, Netolicky J. A

retrospective study of 889 injured permanent teeth. Dent

Traumatol 2010;26:466-75. Crossref

21. Chan YM, Williams S, Davidson LE, Drummond BK.

Orofacial and dental trauma of young children in Dunedin,

New Zealand. Dent Traumatol 2011;27:199-202. Crossref

22. Glendor U. Aetiology and risk factors related to traumatic

dental injuries—a review of the literature. Dent Traumatol

2009;25:19-31. Crossref

23. Zaragoza AA, Catalá M, Colmena ML, Valdemoro C.

Dental trauma in schoolchildren six to twelve years of age.

ASDC J Dent Child 1998;65:492-4,439.

24. Kania MJ, Keeling SD, McGorray SP, Wheeler TT, King GJ.

Risk factors associated with incisor injury in elementary

school children. Angle Orthod 1996;66:423-32.

25. Andersson L, Andreasen JO. Important considerations

for designing and reporting epidemiologic and clinical

studies in dental traumatology. Dent Traumatol

2011;27:269-74. Crossref