Aetiological bases of 46,XY disorders of sex development in the Hong Kong Chinese population

Hong Kong Med J 2015 Dec;21(6):499–510 | Epub 16 Oct 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144402

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Aetiological bases of 46,XY disorders of sex development in the Hong Kong Chinese population

Angel OK Chan*, MD, FHKAM (Pathology)1;

WM But*, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2;

CY Lee, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)3;

YY Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4;

KL Ng, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)5;

PY Loung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)6;

Almen Lam, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)5;

CW Cheng, MSc1;

CC Shek, MB, BS, FRCPath1;

WS Wong, MB, ChB, FHKCPath1;

KF Wong, MD, FHKCPath1;

MY Wong, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2;

WY Tse, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2

1 Department of Pathology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong

Kong

3 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Caritas Medical

Centre, Shamshuipo, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Kwong Wah

Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

5 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, United Christian

Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

6 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret

Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

* AOK Chan and WM But have equal contribution in this study

Corresponding author: Dr Angel OK Chan (cok436@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Objective: Disorders of sex development are due

to congenital defects in chromosomal, gonadal, or

anatomical sex development. The objective of this

study was to determine the aetiology of this group

of disorders in the Hong Kong Chinese population.

Design: Case series.

Setting: Five public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Patients: Patients with 46,XY disorders of

sex development under the care of paediatric

endocrinologists between July 2009 and June 2011.

Main outcome measures: Measurement of serum

gonadotropins, adrenal and testicular hormones,

and urinary steroid profiling. Mutational analysis

of genes involved in sexual differentiation by direct

DNA sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent

probe amplification.

Results: Overall, 64 patients were recruited for the

study. Their age at presentation ranged from birth

to 17 years. The majority presented with ambiguous

external genitalia including micropenis and severe

hypospadias. A few presented with delayed puberty

and primary amenorrhea. Baseline and post–human

chorionic gonadotropin–stimulated testosterone and

dihydrotestosterone levels were not discriminatory

in patients with or without AR gene mutations. Of

the patients, 22 had a confirmed genetic disease,

with 11 having 5α-reductase 2 deficiency, seven with

androgen insensitivity syndrome, one each with

cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme deficiency,

Frasier syndrome, NR5A1-related sex reversal, and

persistent Müllerian duct syndrome.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that 5α-reductase

2 deficiency and androgen insensitivity syndrome

are possibly the two most common causes of 46,XY

disorders of sex development in the Hong Kong

Chinese population. Since hormonal findings can be

unreliable, mutational analysis of the SRD5A2 and

AR genes should be considered the first-line tests for

these patients.

New knowledge added by this study

- The most common likely causes of 46,XY disorders of sex development (DSD) in our local Chinese population are 5α-reductase 2 deficiency and androgen insensitivity syndrome.

- Blood hormone testing is unreliable in differentiating between androgen insensitivity syndrome and other causes of 46,XY DSD.

- Mutational analysis of the SRD5A2 and AR genes should be considered the first-line investigation in patients with 46,XY DSD.

- When encountering patients with 46,XY DSD, 5α-reductase 2 deficiency and androgen insensitivity syndrome should be considered early as their presence has implications for treatment and prognosis.

Introduction

Disorders of sex development (DSD) are defined

as congenital conditions in which development of

chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex is atypical.1

Traditionally, diagnosis in these patients relies on

extensive endocrine investigation. With advances

in the understanding of the genes involved in sexual

determination and differentiation,2 molecular

diagnosis is playing an increasingly important

role and may even overtake the role of hormonal

assessment as the first-line test, with the latter being

reserved for assessment of disease severity rather

than diagnosis.3

One of the most common causes of 46,XY DSD

in the western population is androgen insensitivity

syndrome (AIS).4 Whether the same is true in our

local population remains unknown. We performed a

prospective multicentre study to explore the possible

aetiological basis of 46,XY DSD in the Hong Kong

Chinese population.

Methods

Patients

Patients who were referred to a paediatric

endocrinologist for the first time or were followed up

in their clinic at five public hospitals in Hong Kong

between July 2009 and June 2011 were recruited

for the study. Inclusion criteria were 46,XY ethnic

Chinese patients who presented with incompletely

virilised, ambiguous, or completely female external

genitalia. Criteria that suggested DSD at birth were

overt genital ambiguity, apparent female genitalia

with an enlarged clitoris, posterior labial fusion,

or an inguinal/labial mass, apparent male genitalia

with bilateral undescended testes, micropenis,

isolated perineal hypospadias, or mild hypospadias

with undescended testes, and discordance between

genital appearance and prenatal karyotype.1

Micropenis is defined as stretched penile length of

<2.5 cm based on the published norm for Chinese.1

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patients and/or parents and the study was approved

by the local ethics committee. None of the patients/parents refused to participate in the study although

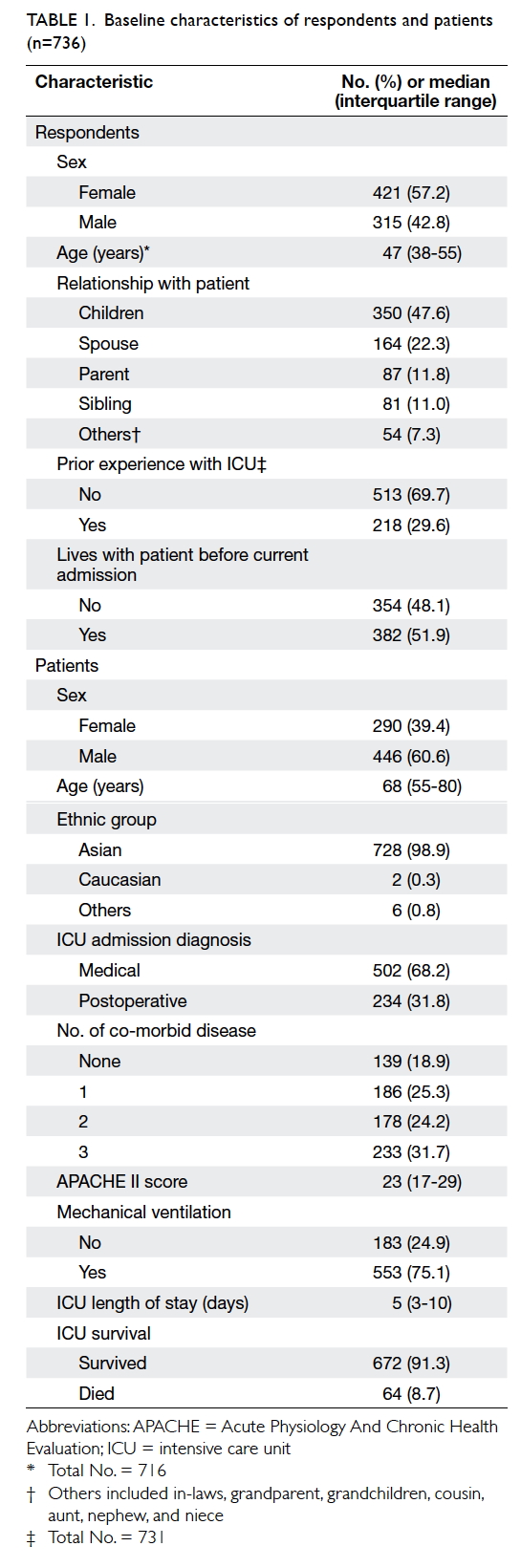

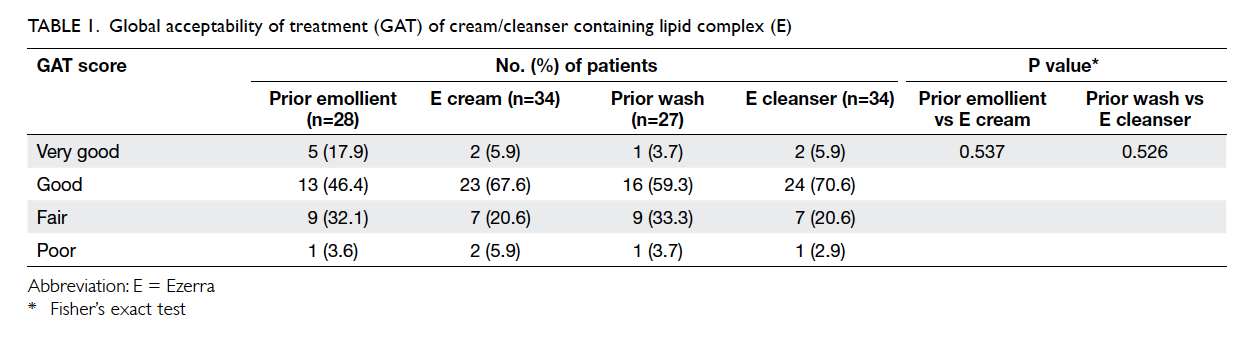

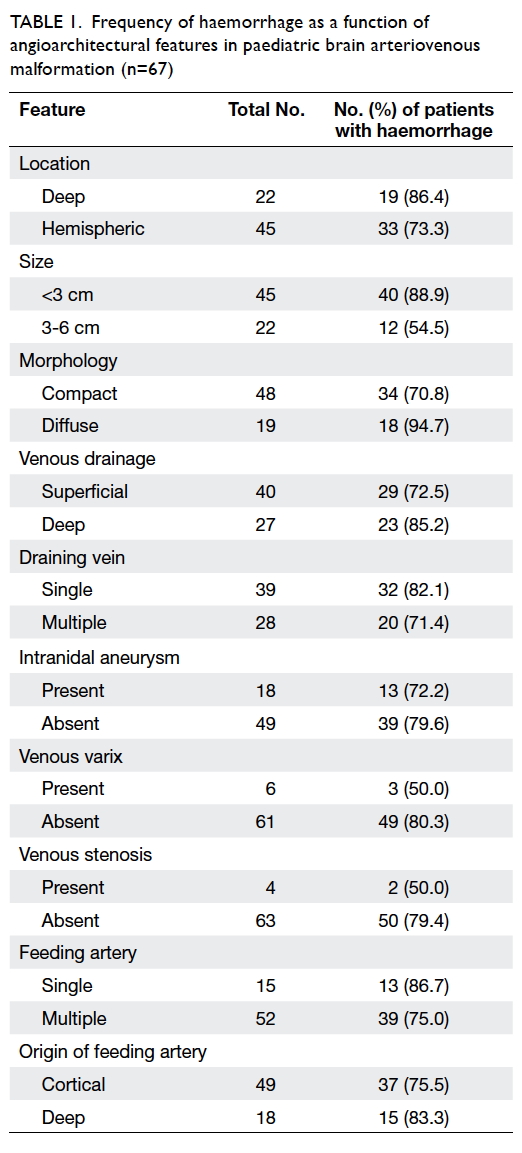

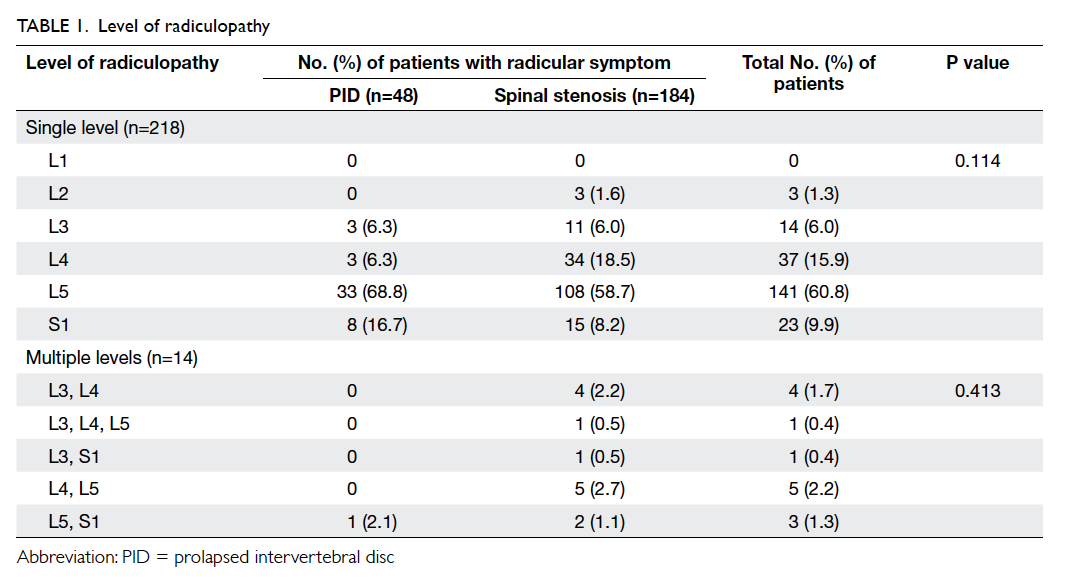

seven refused genetic testing (Table 1).

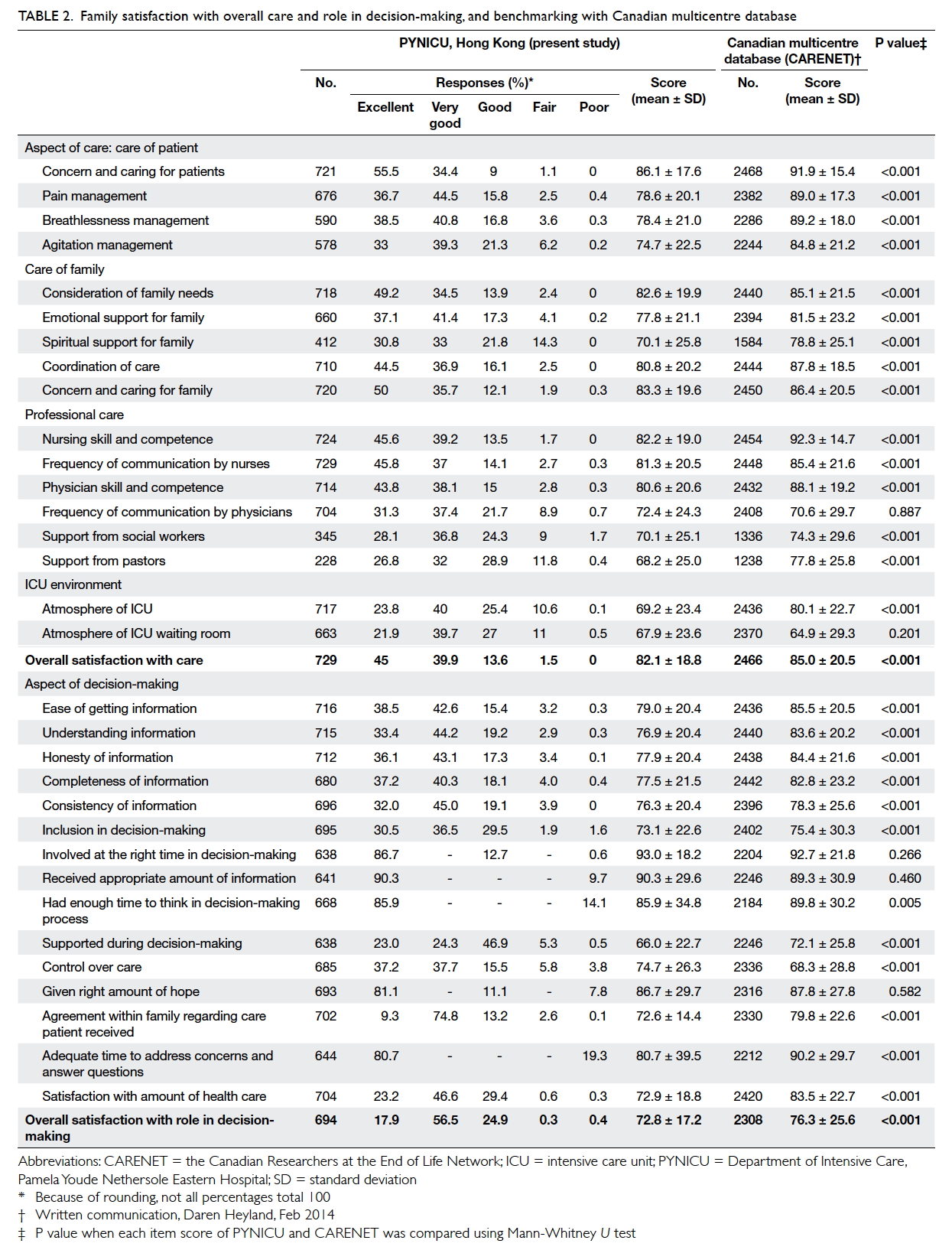

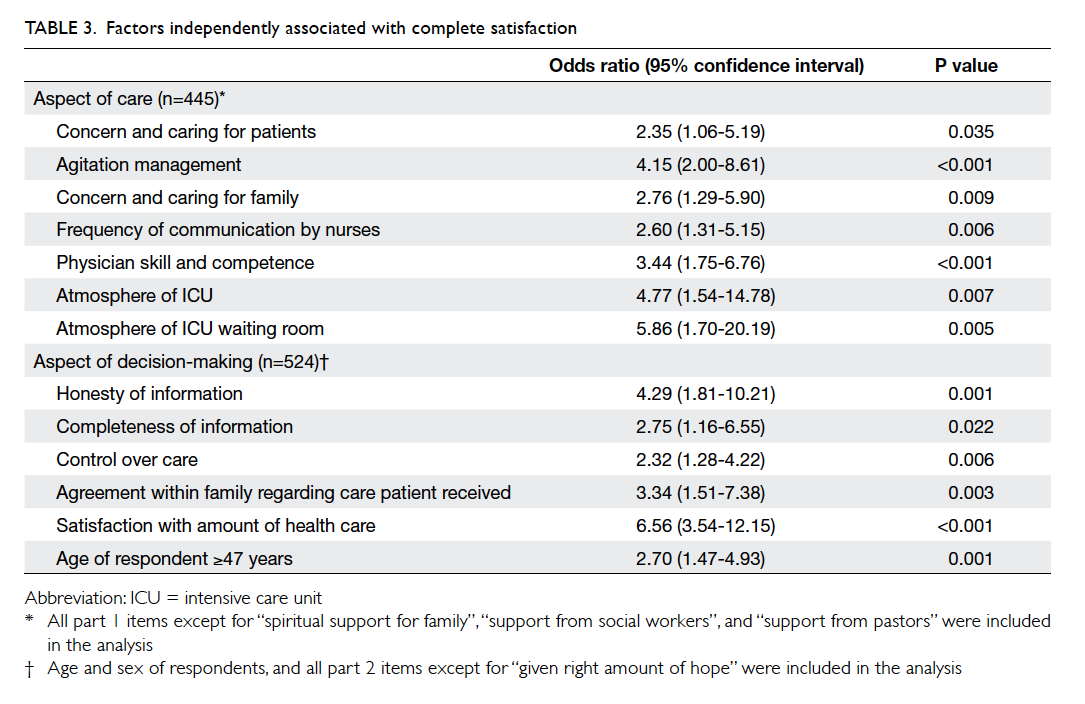

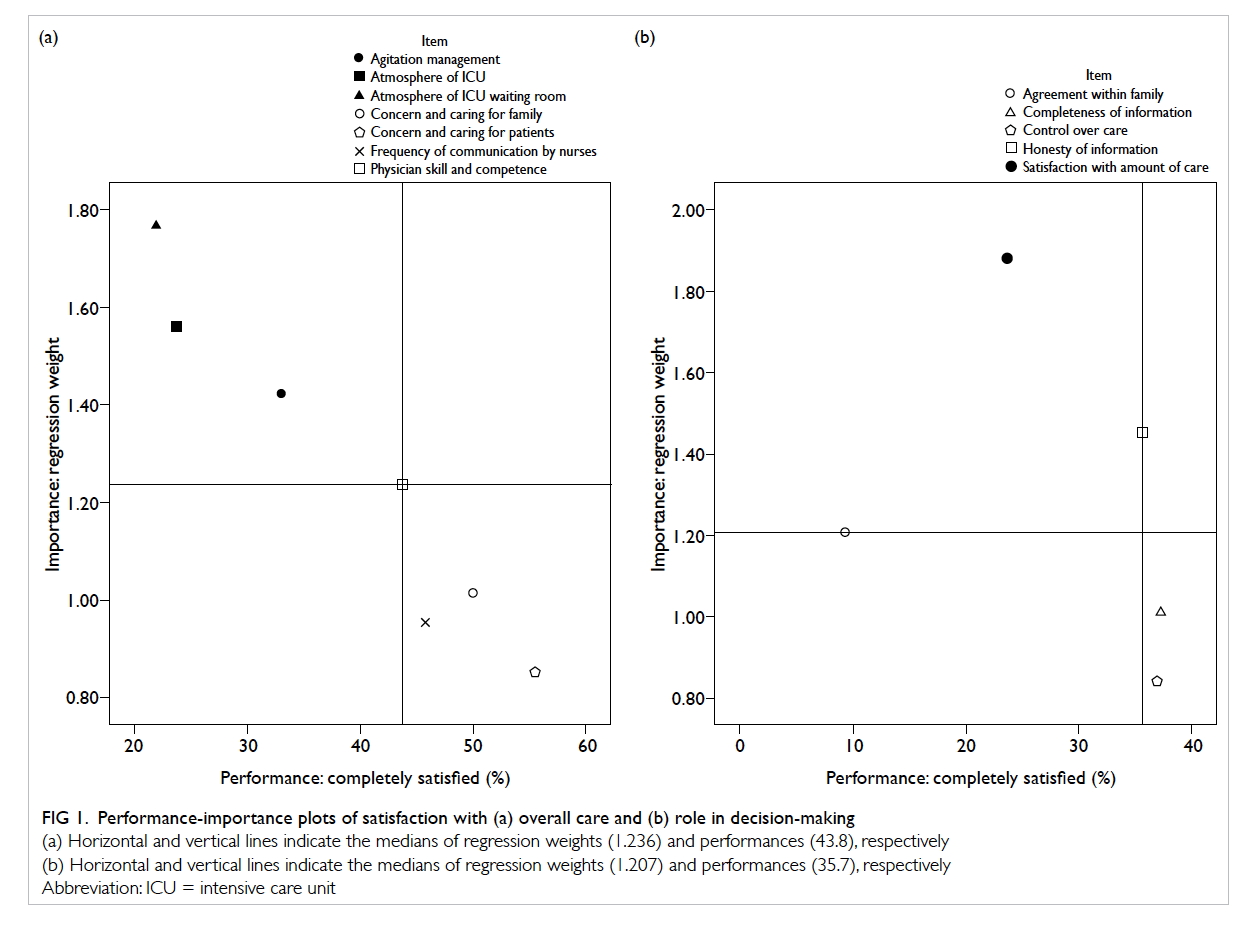

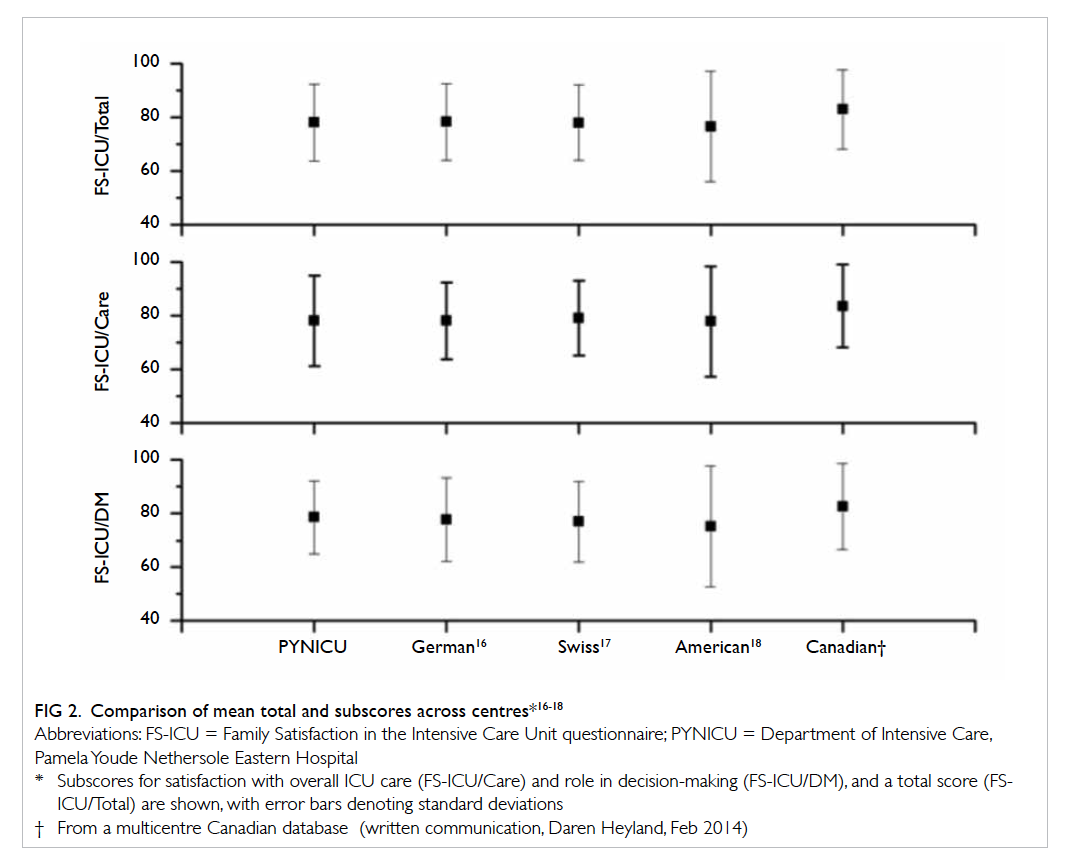

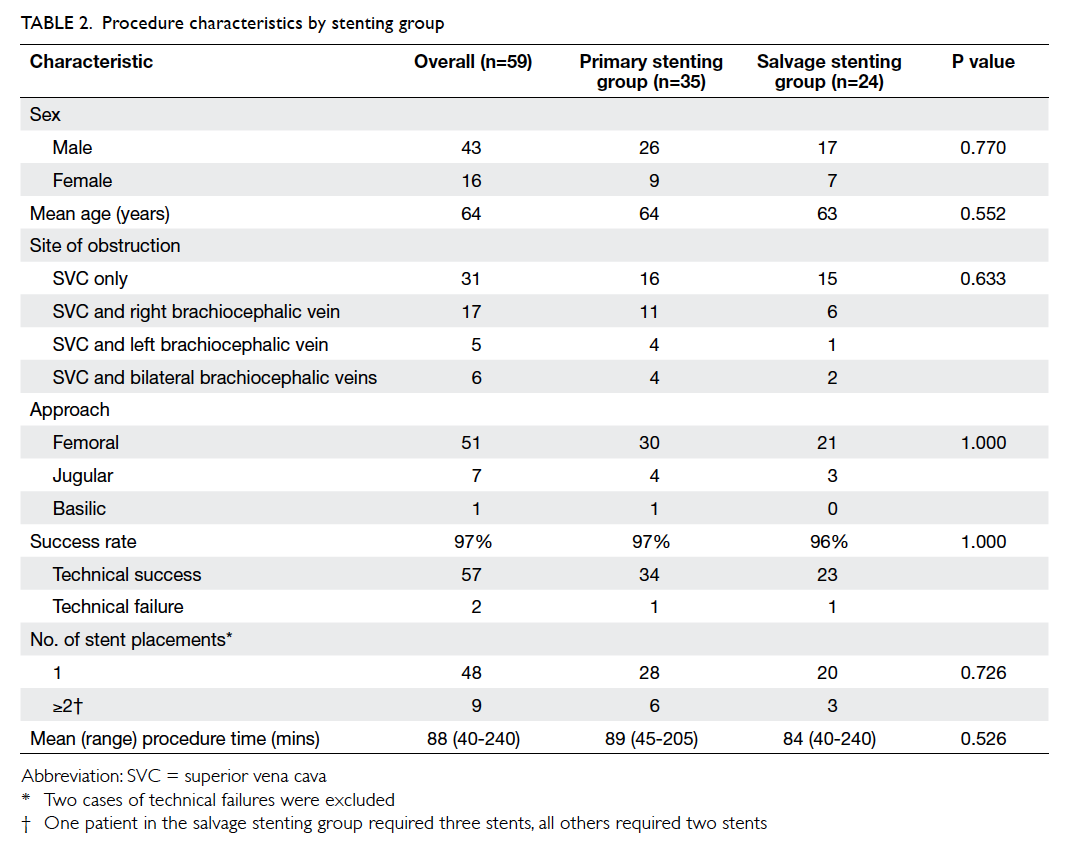

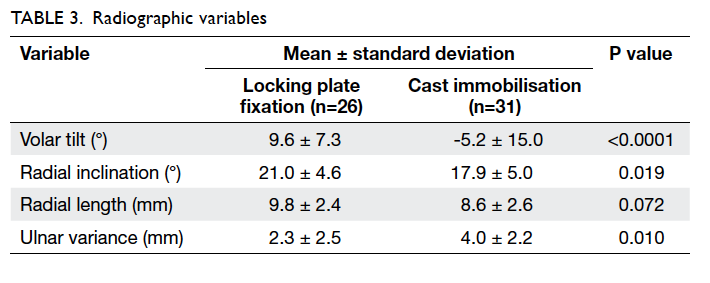

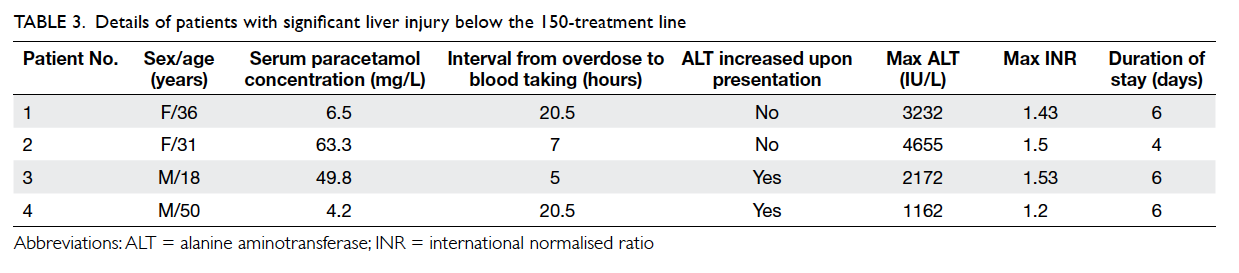

Table 1. The clinical and hormonal findings of 64 patients with 46,XY disorders of sex development recruited in this study. Those baseline hormonal results below the age- and gender-specific reference limits are underlined, those above are in bold

Hormone analysis

Blood was taken from patients for electrolyte

and baseline endocrine assessment and included

measurement of cortisol, 17-hydroxyprogesterone

(17-OHP), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate,

testosterone (T), androstenedione (A4),

dihydrotestosterone (DHT), anti-Müllerian

hormone (AMH), and gonadotropins. Human

chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) stimulation test was

performed to test for testicular Leydig cell function.

The short synacthen test was also performed when

indicated.

Cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate,

and gonadotropins were measured by electro-chemiluminescence

immunoassay (Modular

Analytics E170; Roche, Mannheim, Germany); T

was measured by a competitive immunoenzymatic

assay (ACCESS 2; Beckman Coulter, Brea [CA], US);

17-OHP was measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry using an in-house

method; AMH was measured by an enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (AMH Gen II ELISA, A73818;

Beckman Coulter, Brea [CA], US); DHT was measured

by radioimmunoassay (DSL9600i; Beckman Coulter,

Prague, Czech Republic); A4 was measured by

solid-phase competitive chemiluminescent enzyme-labelled

immunoassay (L2KAO2, Immulite 2000;

Siemens, Tarrytown [NY], US). Male reference

intervals were considered the most appropriate for

data interpretation in this study.

Urinary steroid profiling

Spot urine from patients under 3 months of age

and 24-hour urine from those at or older than 3

months of age were processed for steroid profiling as

described previously.5

Molecular analysis

DNA was extracted from peripheral whole blood

using a QIAamp DNA blood kit (Qiagen, Hilden,

Germany). Polymerase chain reaction and direct

DNA sequencing were performed on targeted genes

when suggested by the clinical and hormonal findings.

Otherwise all patients had their AR (androgen

receptor) and NR5A1 (steroidogenic factor 1) genes

sequenced. Those patients with negative genetic

findings were subjected to multiplex ligation-dependent

probe amplification (MLPA) analysis

(P185 Intersex probemix; P074 Androgen Receptor

probemix and P334 Gonadal probemix; MRC-Holland)

to test for gross deletion or gene duplication.

The results were analysed by Coffalyser.Net.

Family genetic studies were performed when

mutation(s) were identified in the index patients.

In-silico analysis for novel missense mutations

The functional effect of novel missense mutations

detected was tested by online in-silico analysis

software SIFT, PolyPhen2, and Align GVGD.

Results

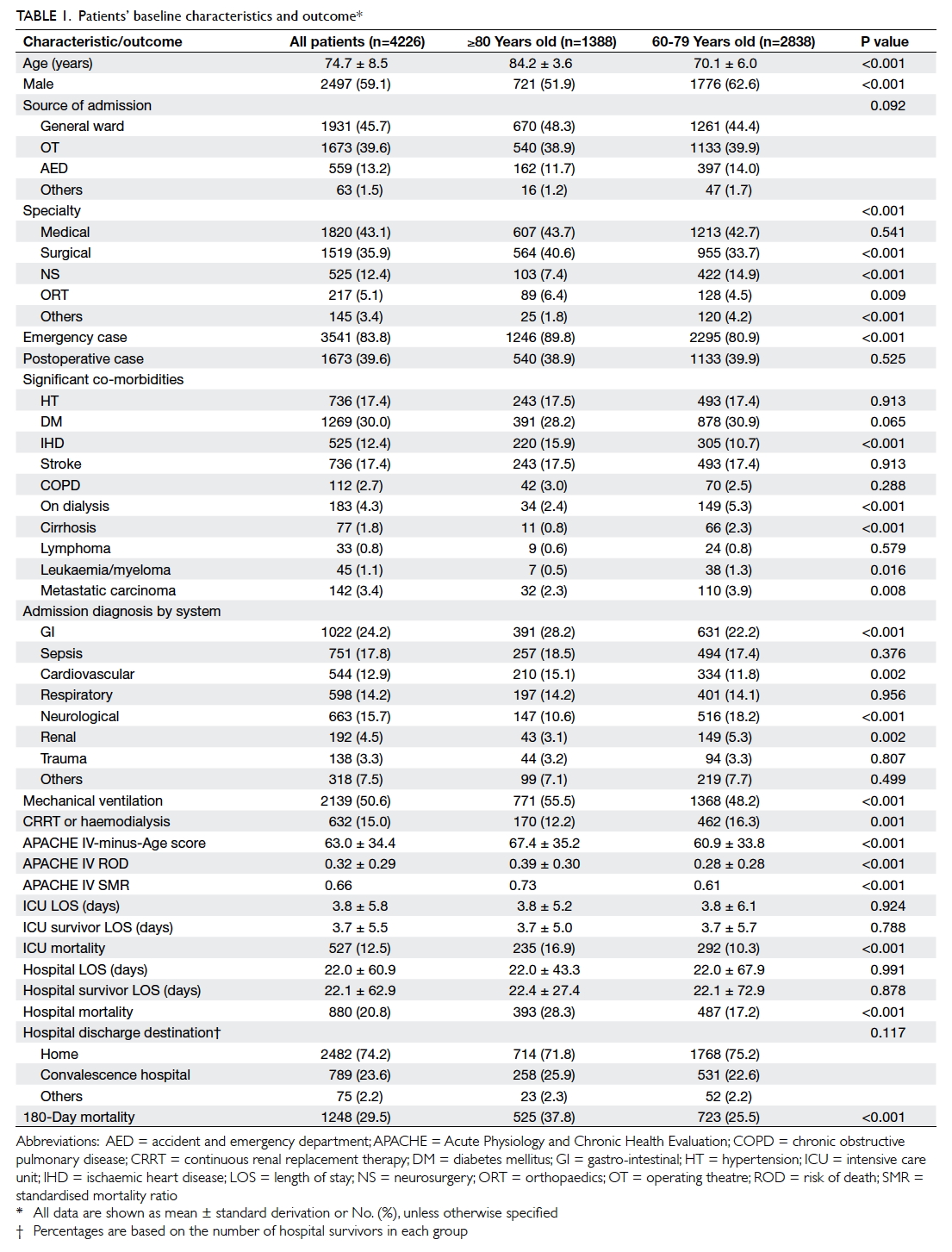

Overall, 64 patients (53 male, 11 phenotypic female),

including 14 new patients, with 46,XY DSD were

recruited into the study. The clinical and hormonal

findings of individual patients are listed in Table 1.

A genetic diagnosis was made in 10 patients prior

to the study. Other major structural abnormalities

were evident in eight (Table 2). Their age at presentation ranged from birth to 17 years. Five

(8%) were born prematurely (24-35 weeks) and

nine (14%) with low birth weight (0.59-2.32 kg). All

had non-consanguineous parents. A family history

of sexual ambiguity was present in six. Overall, 61

(95%) presented with ambiguous external genitalia

including 15 with isolated micropenis, eight

with isolated severe hypospadias, and one with

discordance between the prenatal karyotype and the

postnatal phenotype. Three presented after birth,

one each with inguinal hernia, delayed puberty, and

primary amenorrhoea.

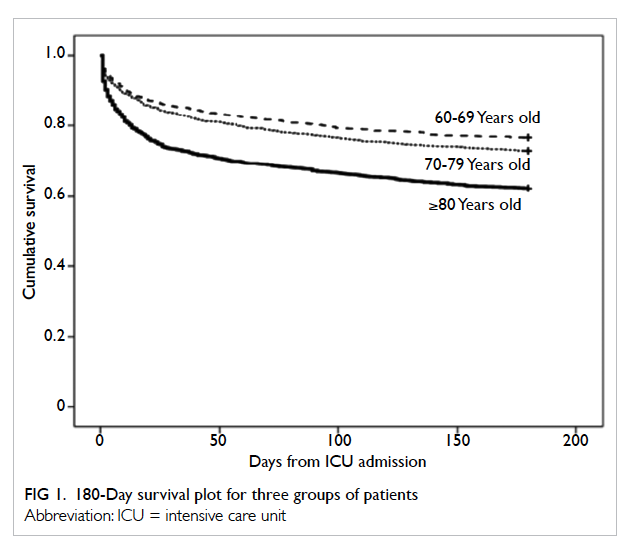

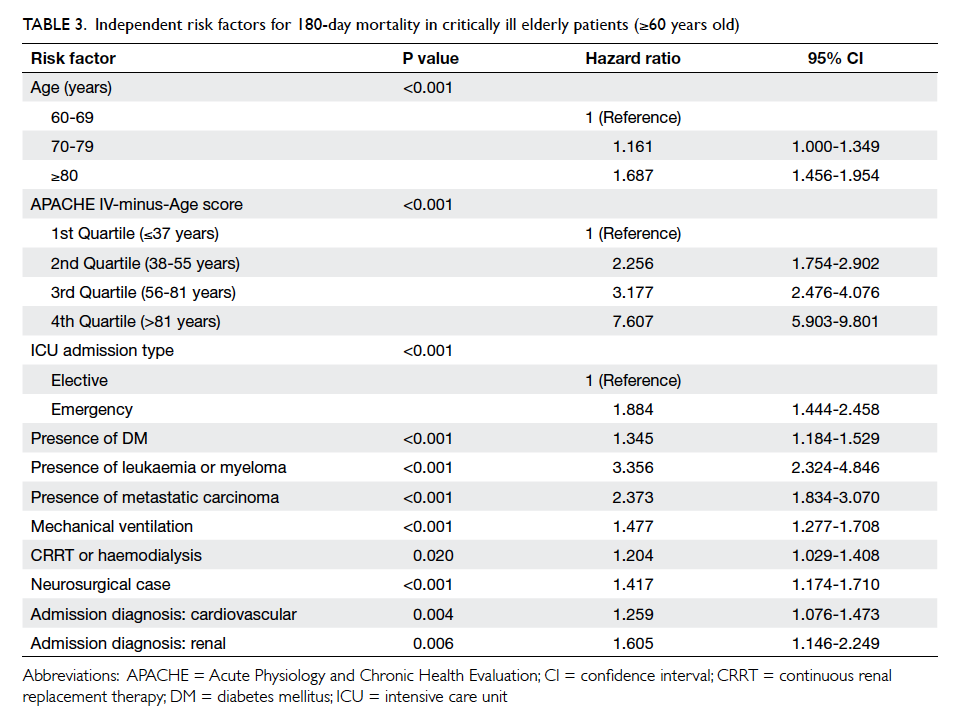

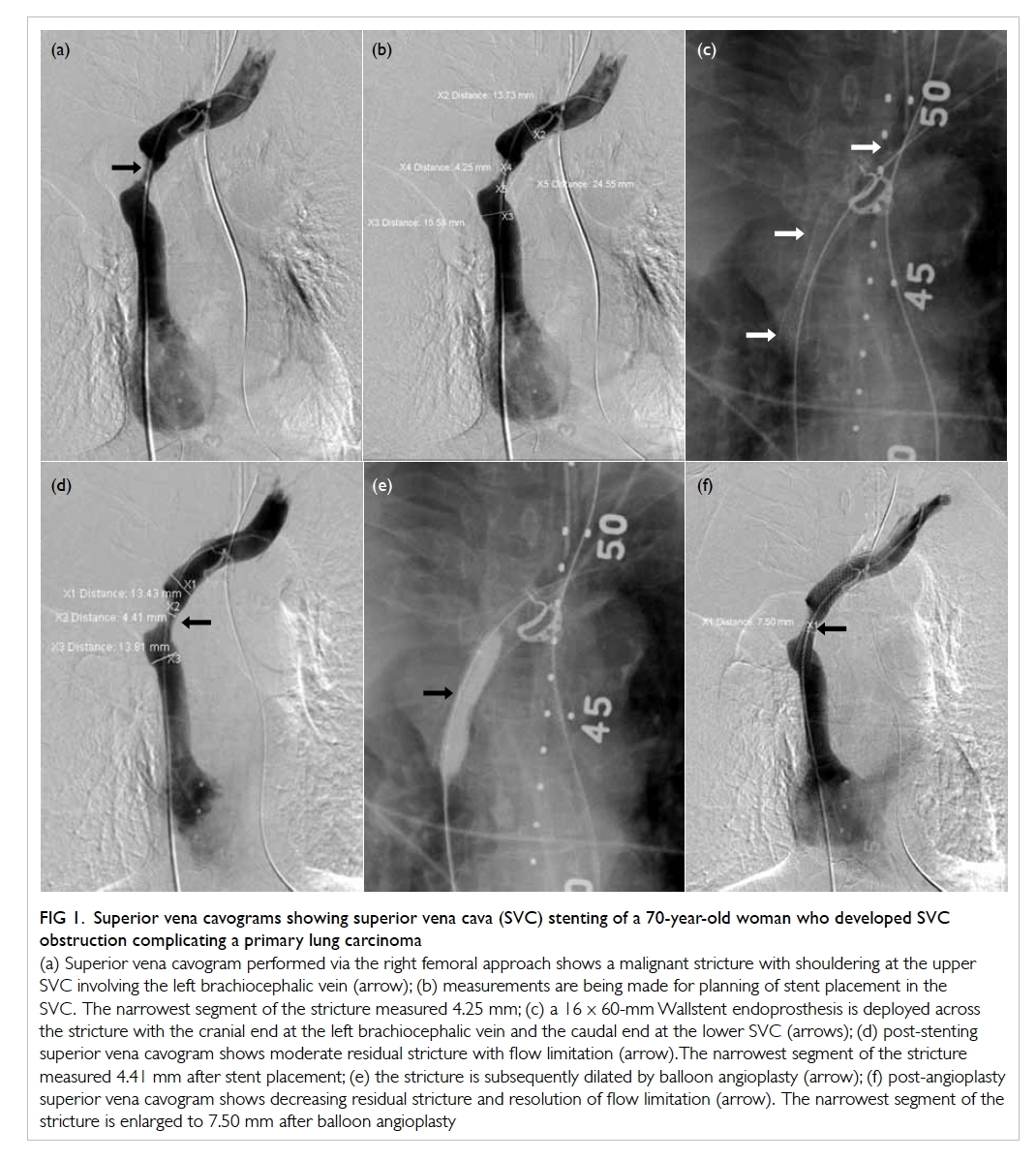

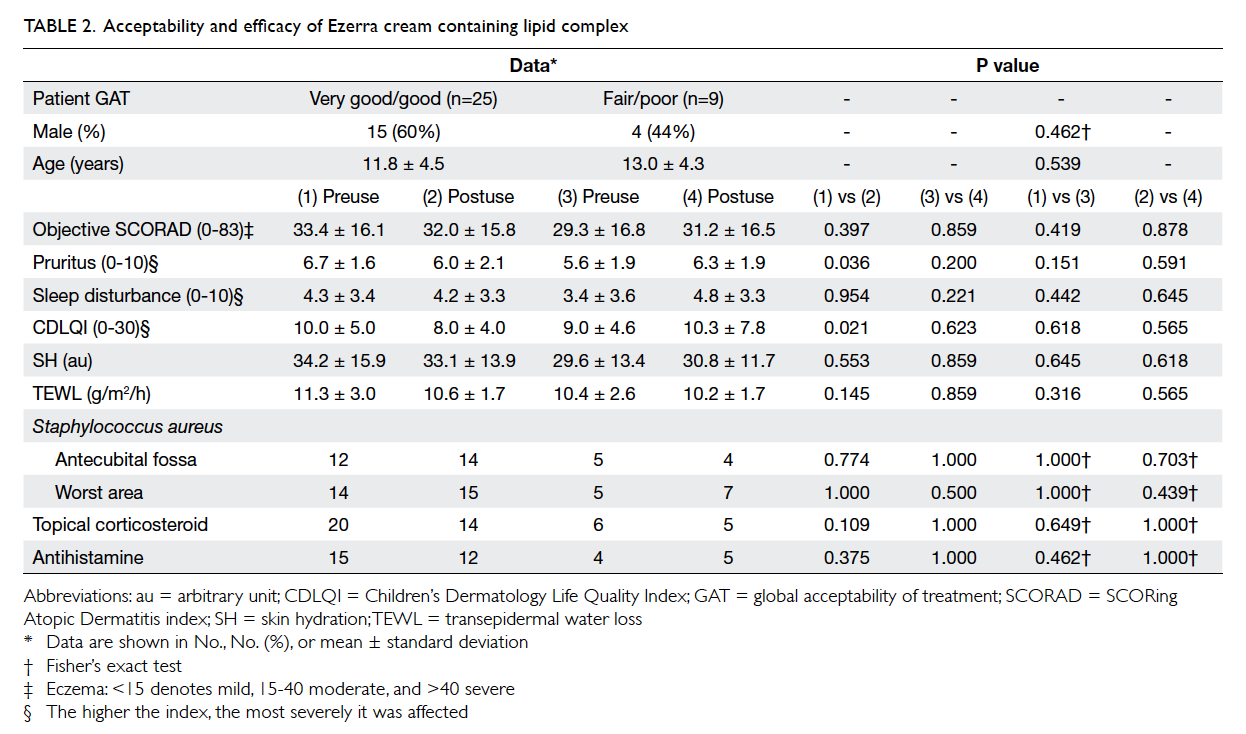

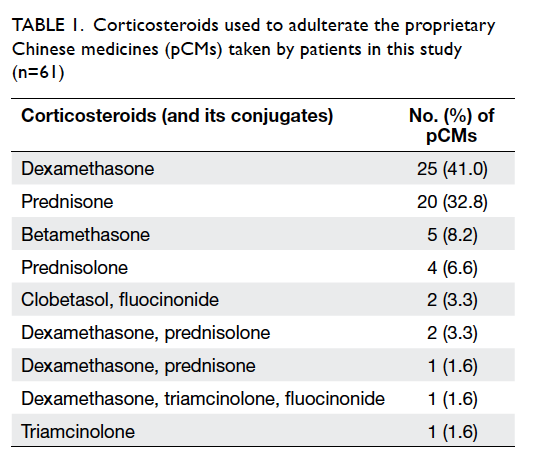

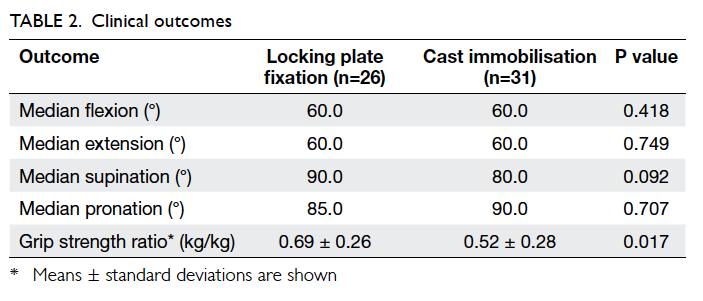

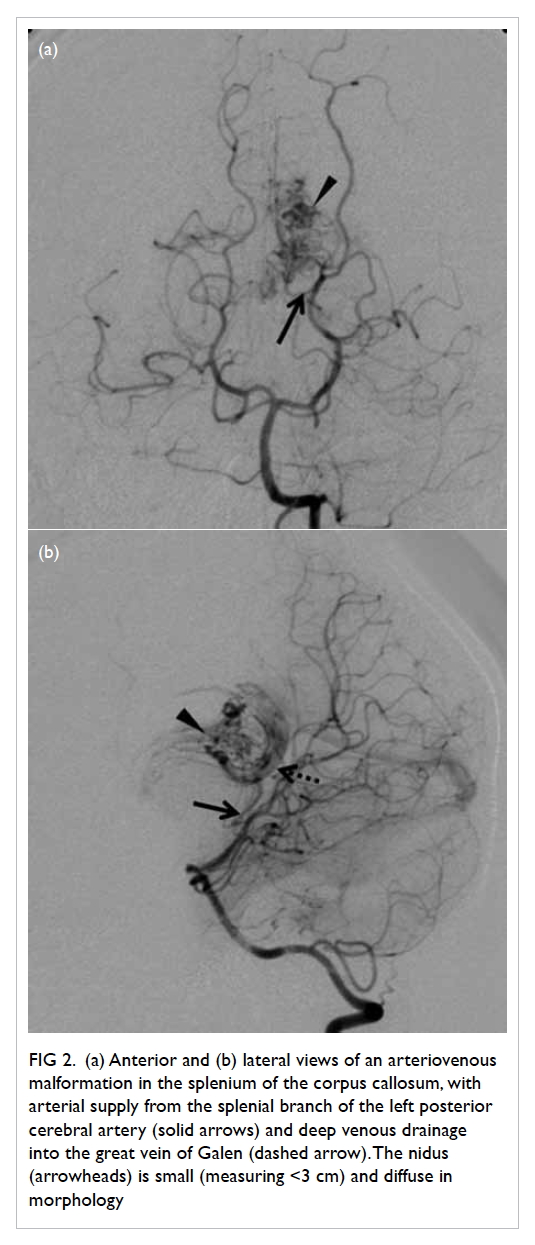

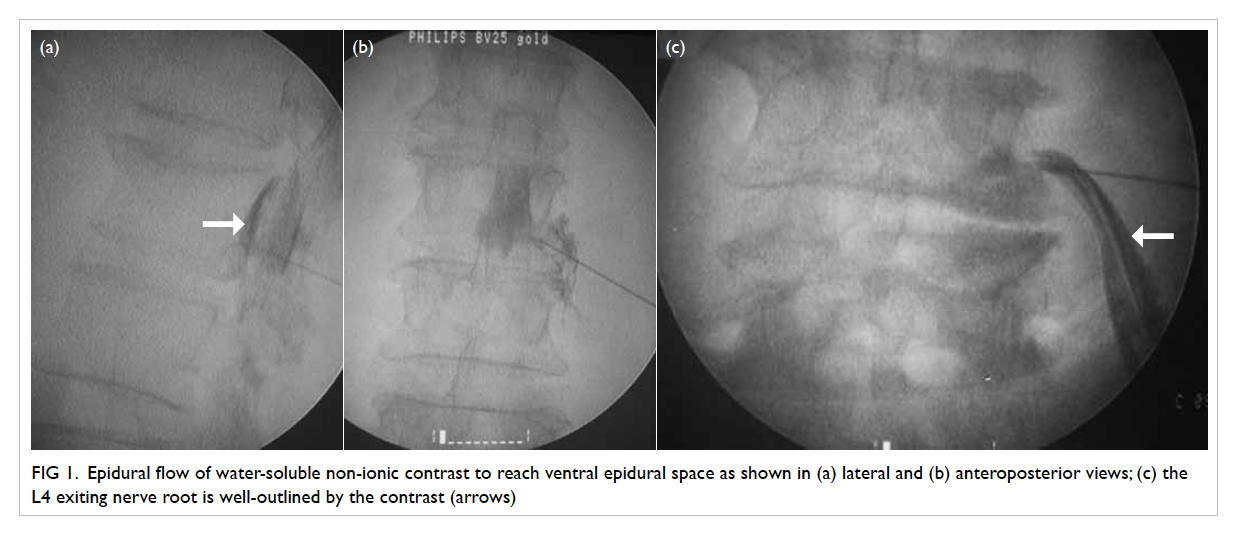

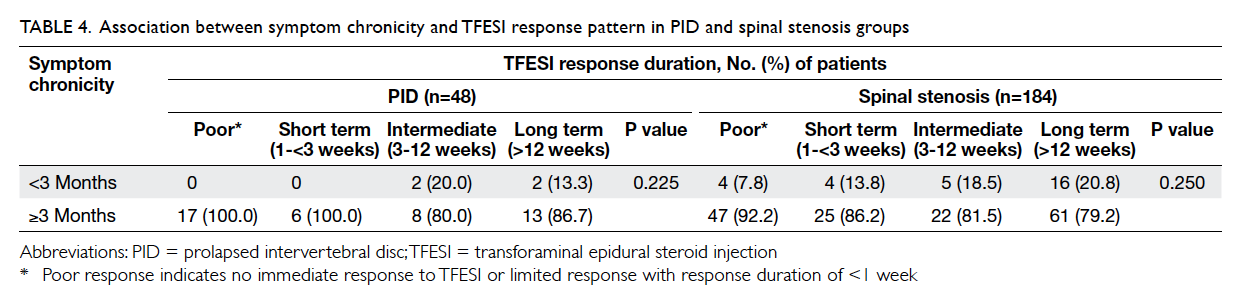

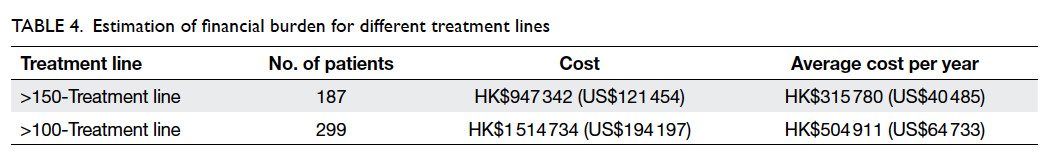

Regarding the hormonal findings, Figure 1 shows the baseline and post-hCG–stimulated T and

DHT levels in patients with mutations detected in

the AR gene and those without, where the results

overlapped between the two groups. Eight patients

(patients 13, 19, 21, 30, 31, 40, 49, and 56) underwent

short synacthen test and with the exception of

patient 19, all had an adequate cortisol response

(>550 nmol/L). Patient 27 had a relatively low

T/A4 ratio before and after hCG stimulation but

sequencing revealed no mutation in his HSD17B3

(17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase III) gene. All

other patients had unremarkable T and A4 levels, as well as T/A4 ratio.

Figure 1. Responses in (a) testosterone and (b) dihydrotestosterone levels upon hCG stimulation in patients with AR mutation (left panel) compared with those without (right panel)

Eleven patients had characteristically low

5α- to 5β-reduced steroid metabolite ratios in

their urine, compatible with the diagnosis of 5α-reductase 2 deficiency (5ARD). This was also

confirmed by mutational analysis of the SRD5A2

(steroid 5α-reductase 2) gene. All other patients had

unremarkable urinary steroid metabolite pattern.

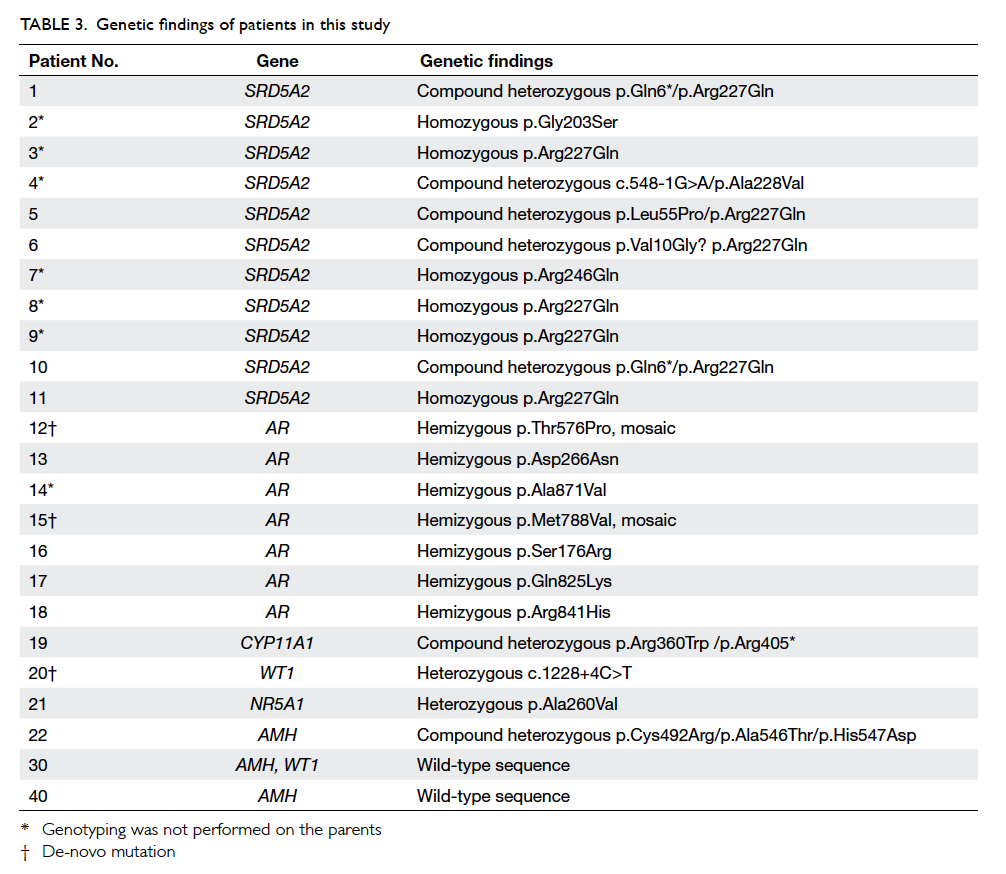

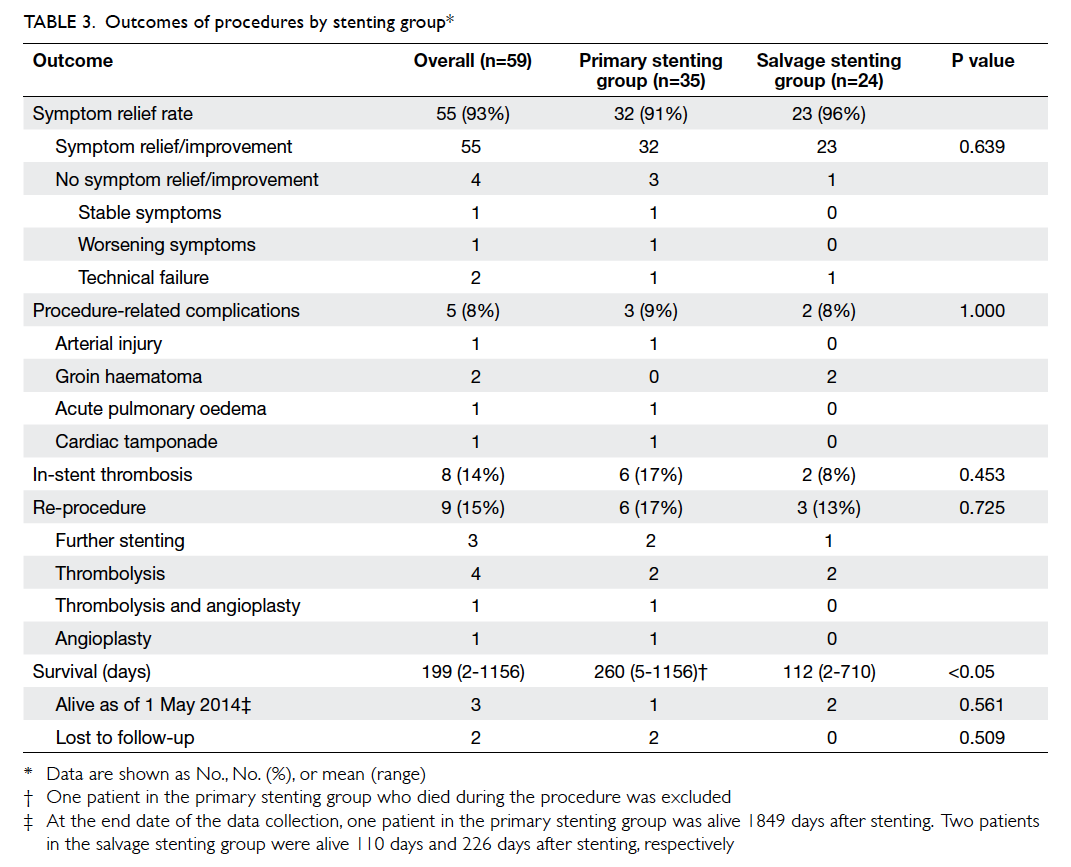

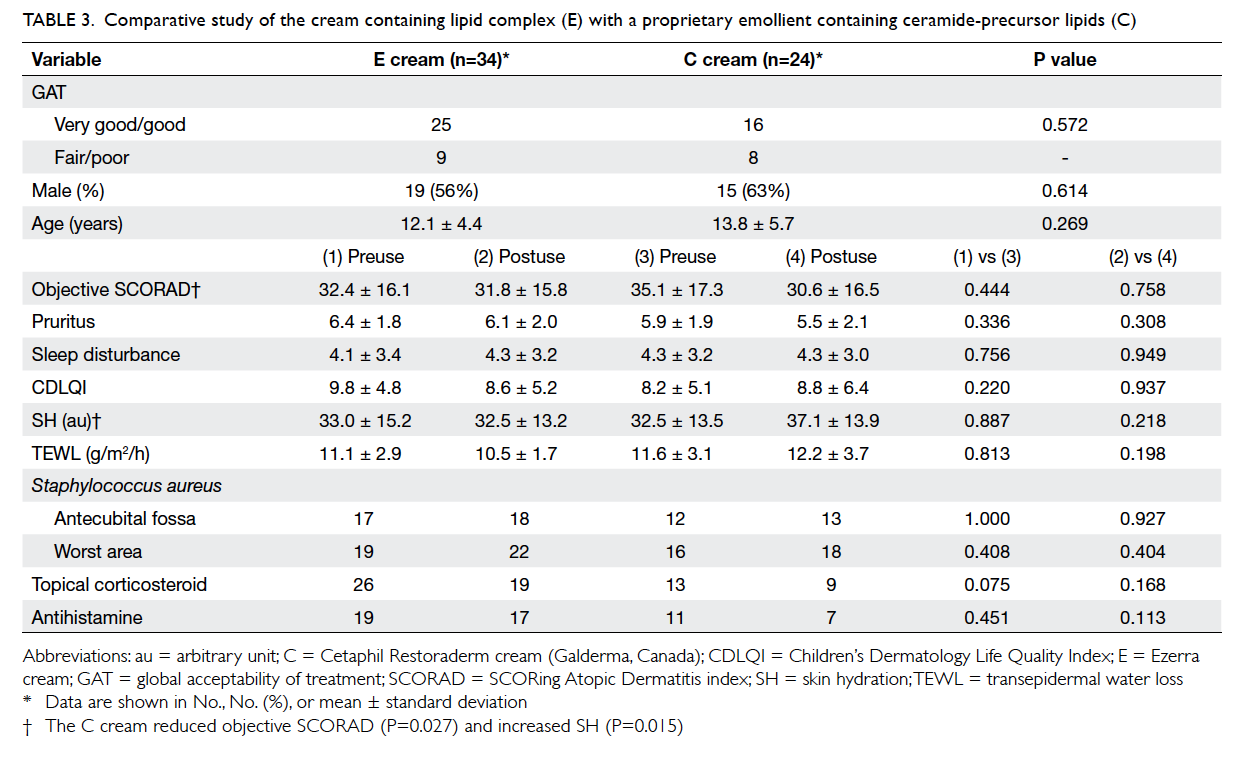

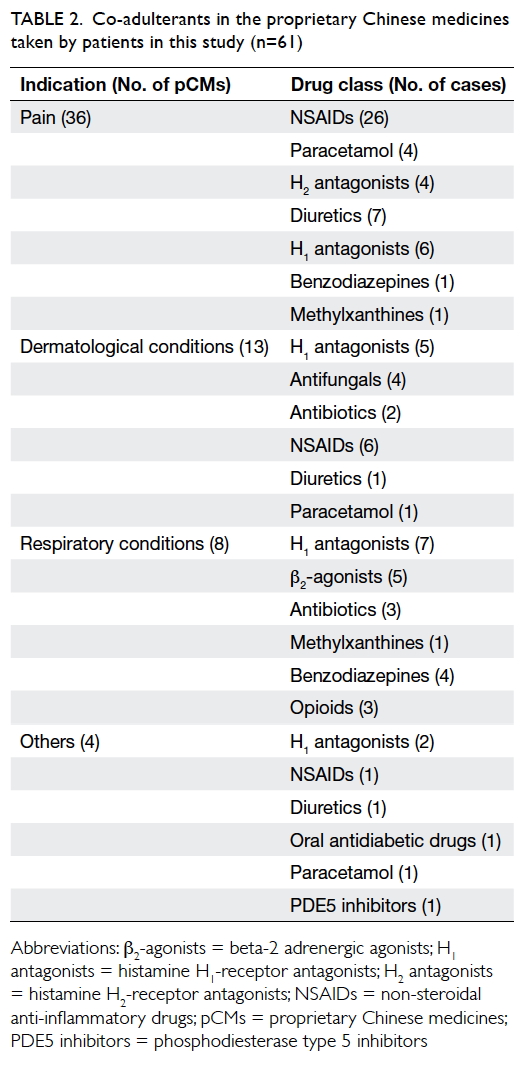

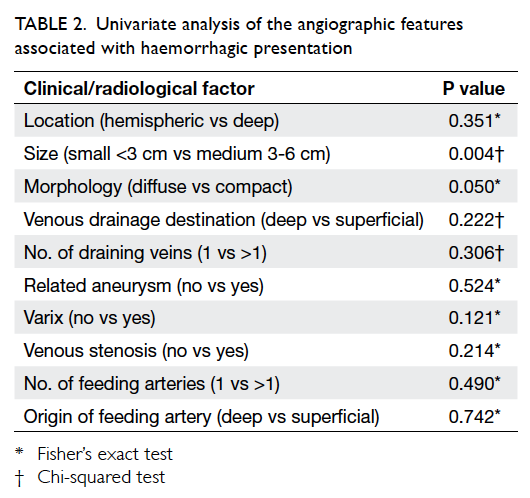

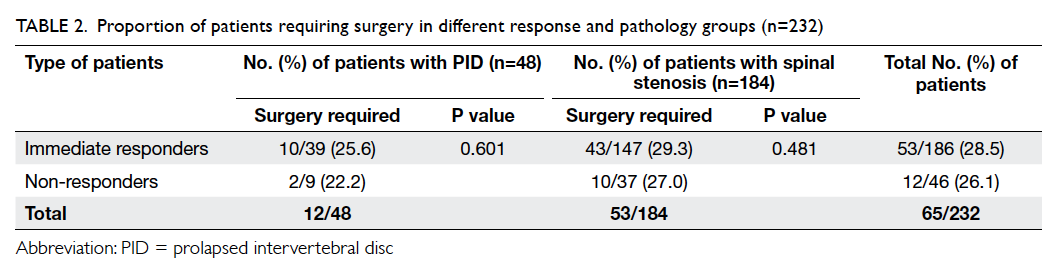

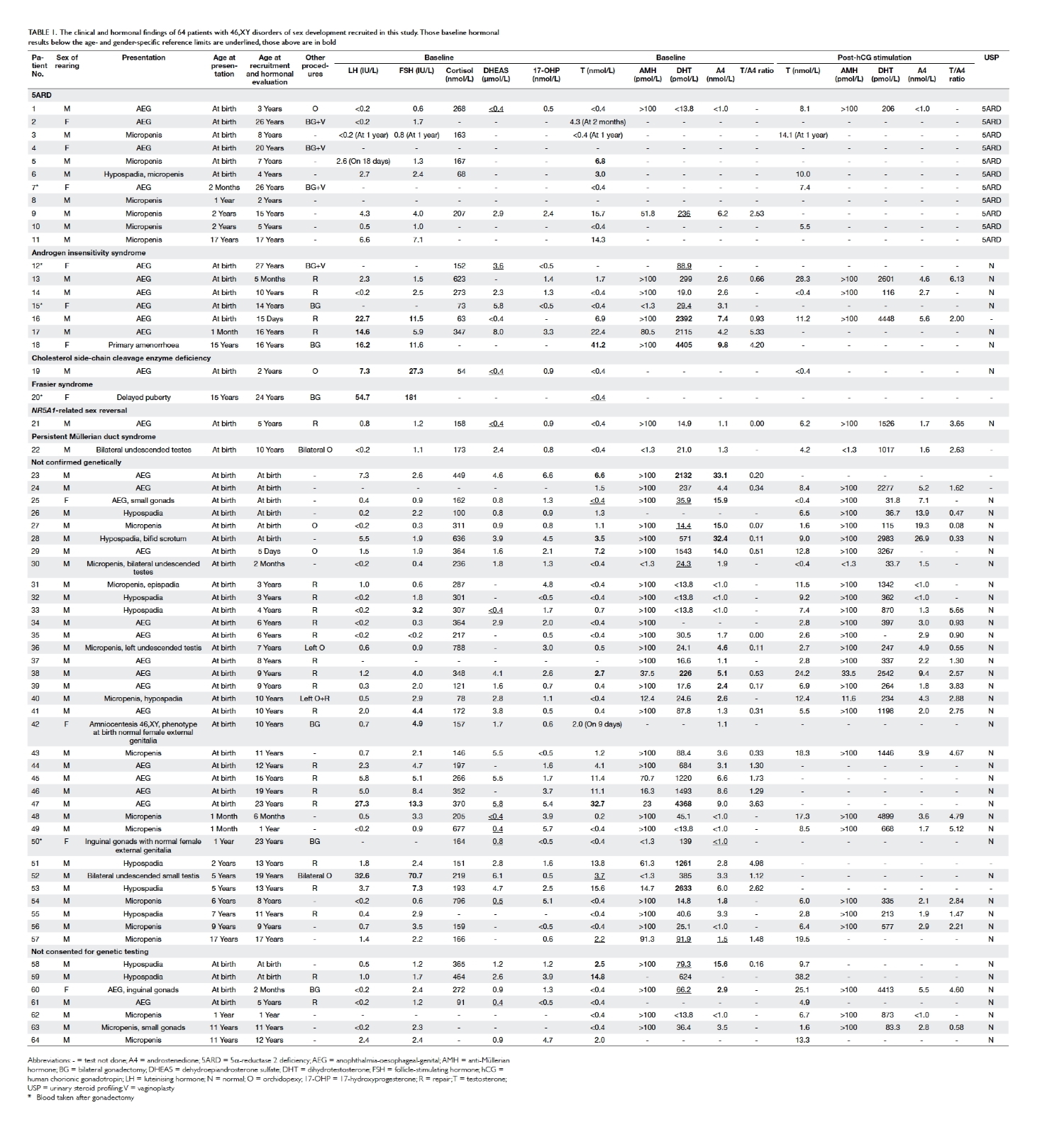

Overall, 22 (39%) patients had a confirmed

genetic diagnosis (Table 3). The most common diagnoses in our cohort were 5ARD (n=11) and AIS

(n=7). Other genetic diagnoses included cholesterol

side-chain cleavage enzyme deficiency (n=1), Frasier

syndrome (n=1), NR5A1-related sex reversal (n=1),

and persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS;

n=1). The clinical and laboratory findings of patients

19 and 20 have been reported previously.6 7 Patients

12 and 15 had de-novo mutations in the AR gene

and were in mosaic pattern. Patient 21 had a novel

missense variant p.Ala260Val detected in his NR5A1

gene. His AMH level was not low, contrary to some

of the previously reported cases.8 There was also a

clinically significant rise in T level after hCG stimulation.

Short synacthen test demonstrated an adequate

cortisol response (baseline: 720 nmol/L; post–adrenocorticotropin hormone: 822 nmol/L). His

father also carried the same heterozygous mutation

although he denied any symptoms of DSD. This

novel genetic variant was not detected in 100 normal

Chinese subjects (control). Patient 22 had bilateral

undescended testes. He underwent orchidopexy

at the age of 1 year during which the presence of

Müllerian duct structures was suspected. Further

workup including pelvic ultrasound revealed

Müllerian duct structures and extremely low AMH

level. The diagnosis of PMDS was confirmed by

the presence of three heterozygous novel missense

variants in the AMH gene (Tables 3 and 4).

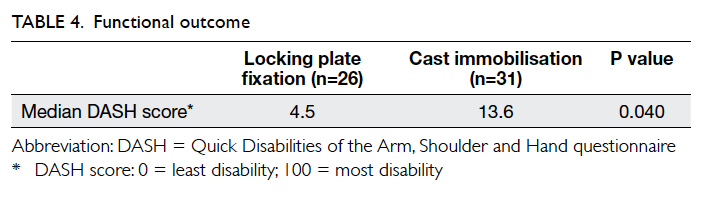

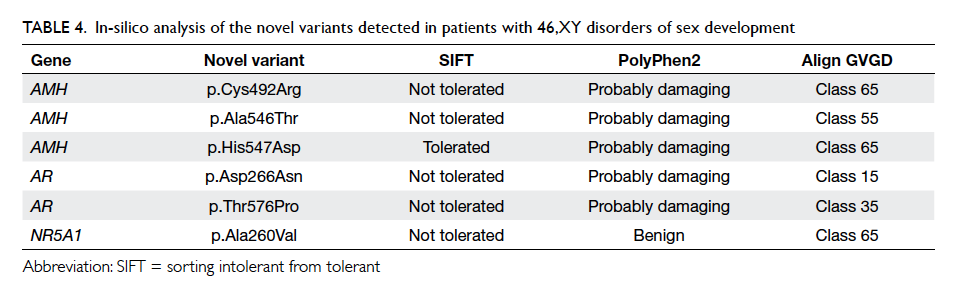

Table 4. In-silico analysis of the novel variants detected in patients with 46,XY disorders of sex development

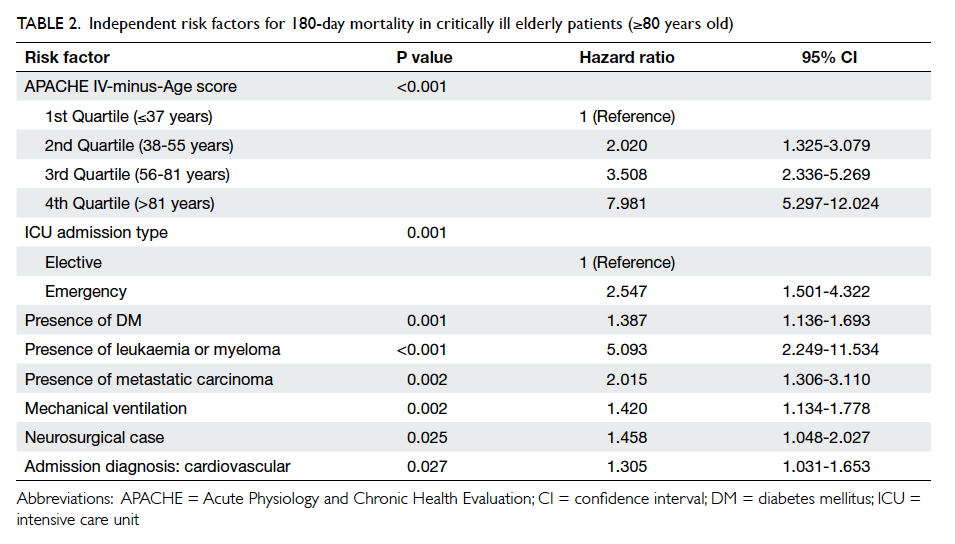

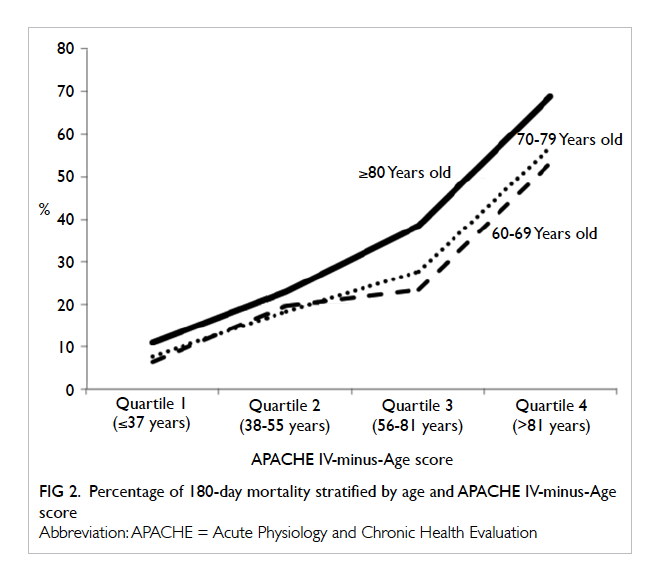

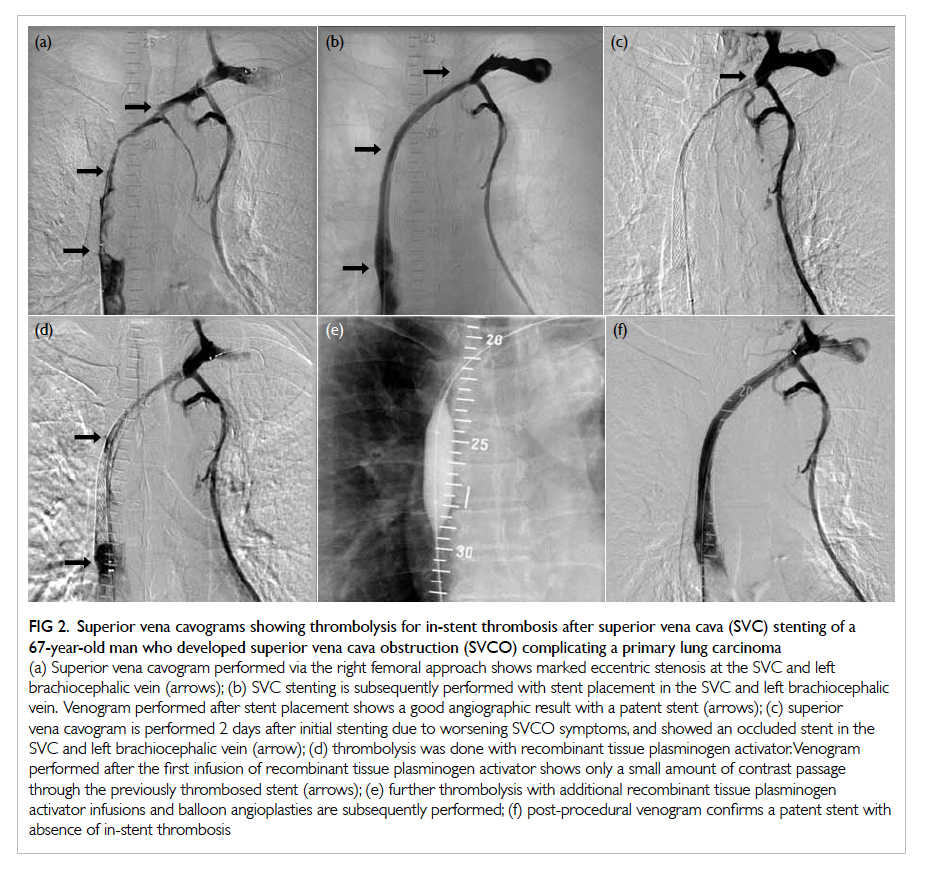

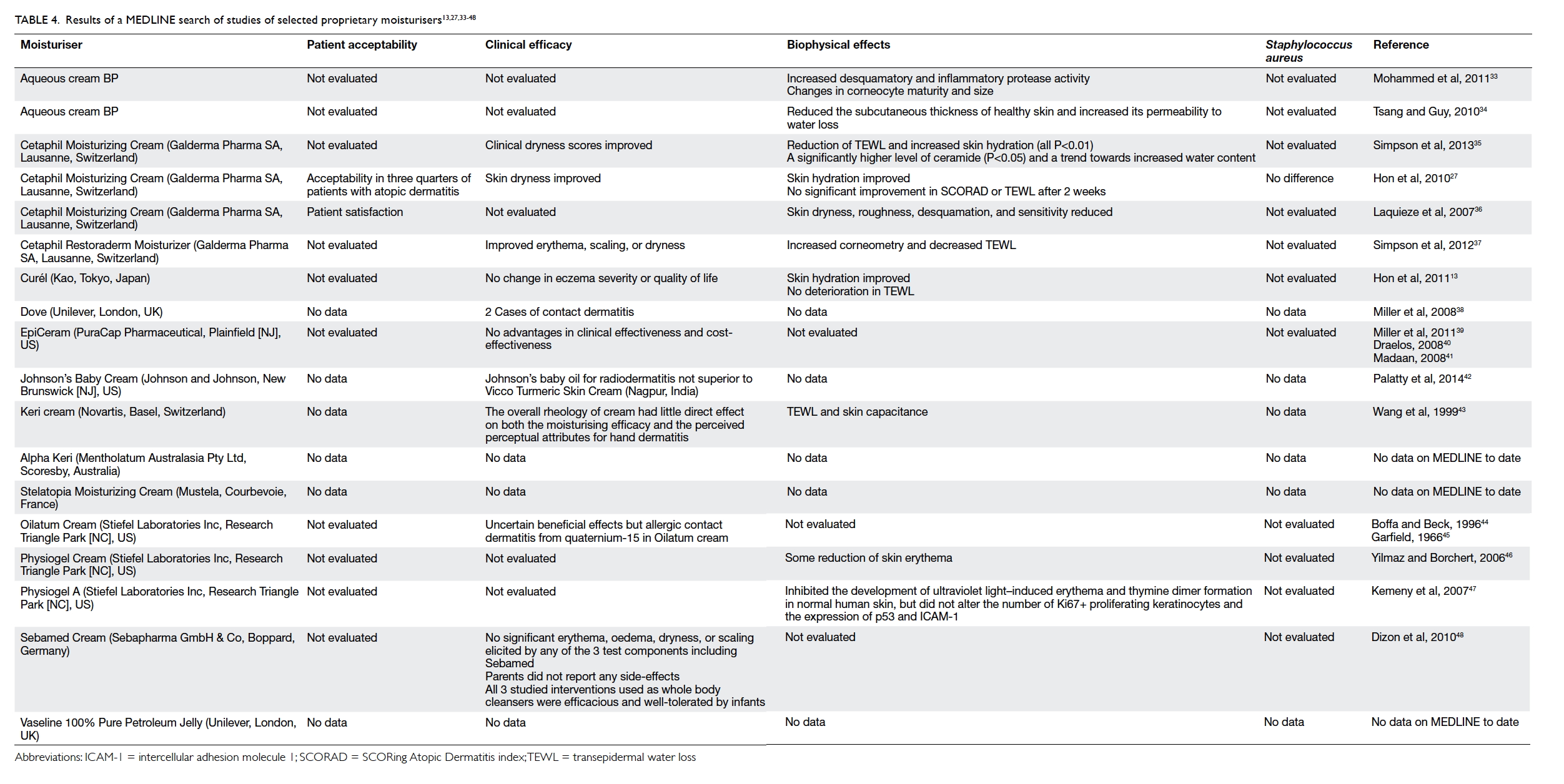

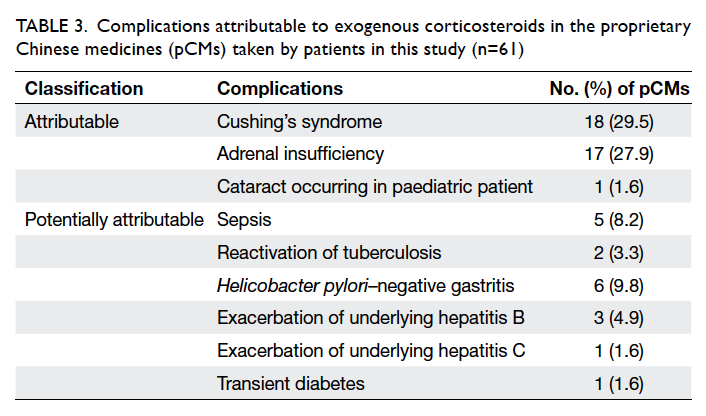

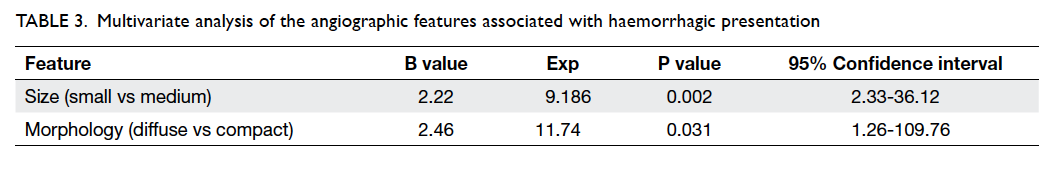

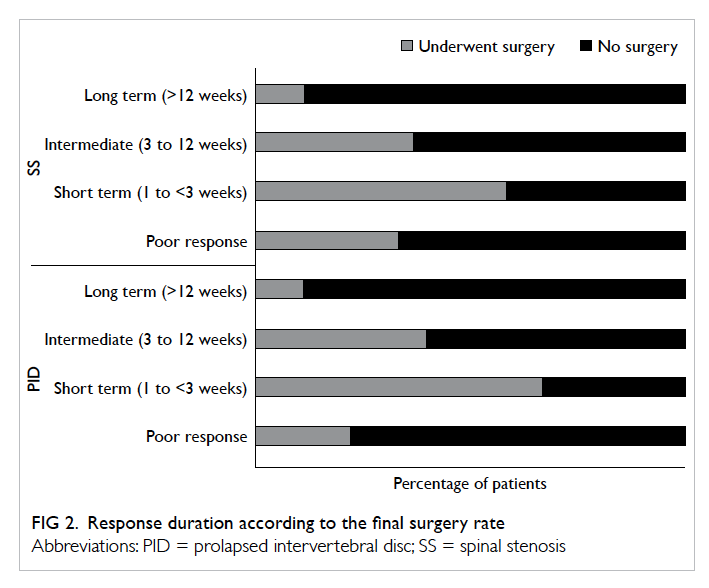

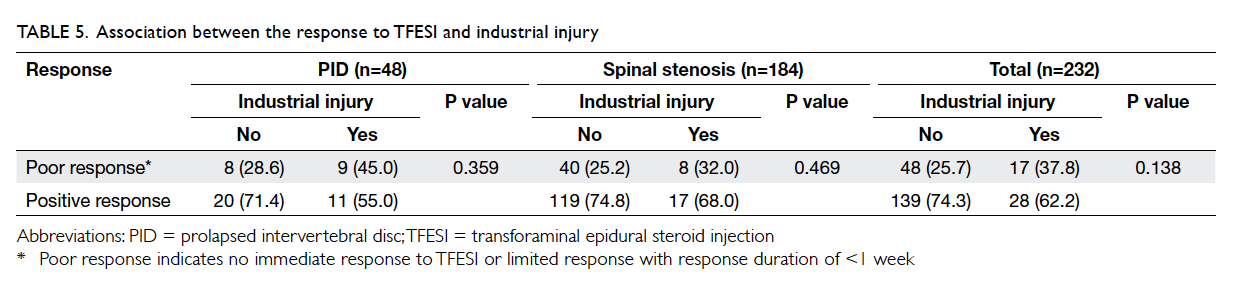

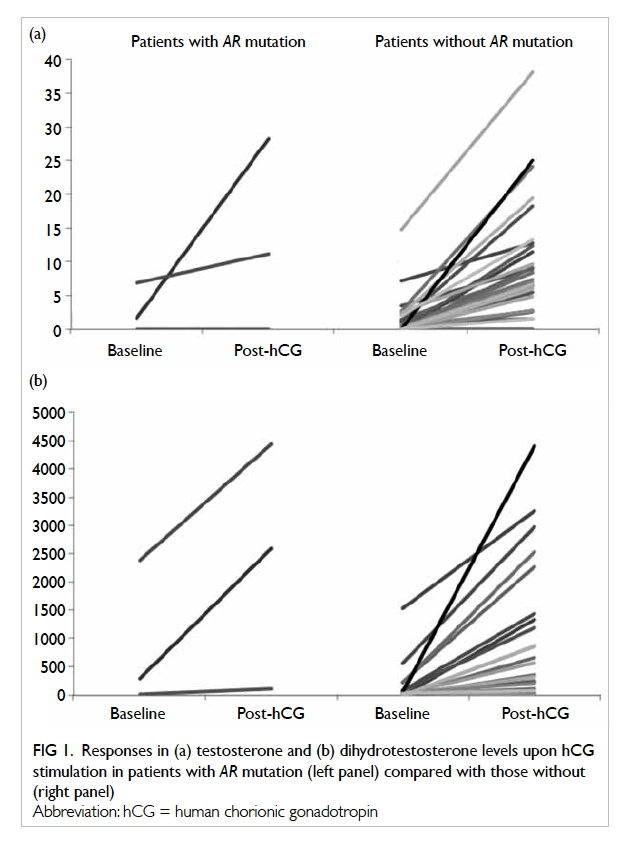

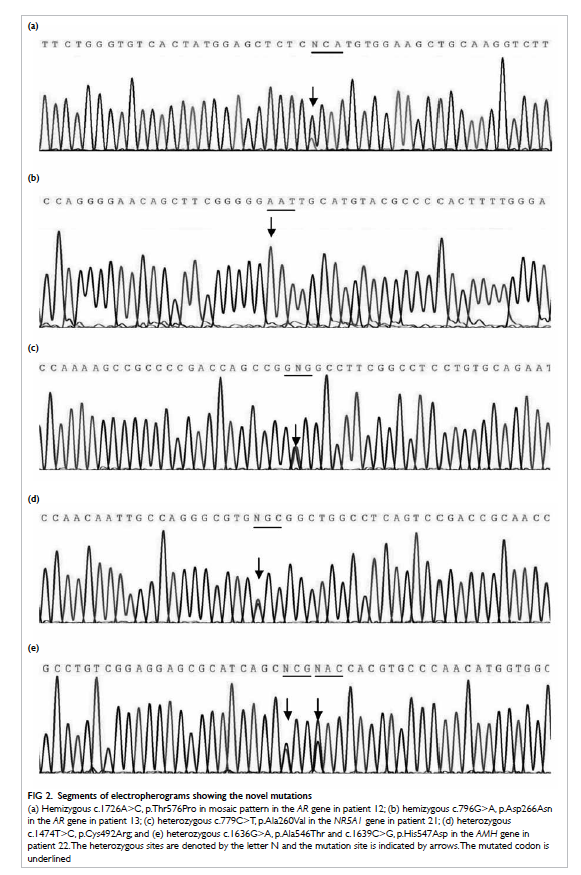

Six novel genetic variants were identified in the

AMH, AR, and NR5A1 genes (Fig 2). At least two of the three in-silico analysis programmes predicted

the variants to be pathogenic (Table 4). Multiple sequence alignment showed that the amino acids

of concern were highly conserved across different

animal species. All these findings support the

pathogenic nature of these variants accounting for

the patients’ phenotypes.

Figure 2. Segments of electropherograms showing the novel mutations

(a) Hemizygous c.1726A>C, p.Thr576Pro in mosaic pattern in the AR gene in patient 12; (b) hemizygous c.796G>A, p.Asp266Asn in the AR gene in patient 13; (c) heterozygous c.779C>T, p.Ala260Val in the NR5A1 gene in patient 21; (d) heterozygous c.1474T>C, p.Cys492Arg; and (e) heterozygous c.1636G>A, p.Ala546Thr and c.1639C>G, p.His547Asp in the AMH gene in patient 22. The heterozygous sites are denoted by the letter N and the mutation site is indicated by arrows. The mutated codon is underlined

Eleven patients were reared as girls because

of severe under-virilisation at birth, including three

with 5ARD, three with AIS, and one with Frasier

syndrome. The underlying genetic causes in the

remaining four patients were undetermined. The

longest follow-up period was 27 years. None of

them has requested change of gender to date. Five

patients (patients 2, 4, 7, 12, and 15) exhibited ‘tom-boy-like’ behaviour during childhood and required

counselling by a clinical psychologist while two

males (patients 17 and 47) requested exogenous T

to augment penile growth after puberty. Patient 20

developed germinoma in her dysgenetic gonad with

no recurrence after surgery.

Discussion

46,XY DSD is a heterogeneous condition caused by

a wide spectrum of disorders. Making an accurate

diagnosis is difficult but important for emergency

medical treatment as some DSDs are associated with

life-threatening Addisonian crisis. In addition, the

diagnosis is essential so that relevant information

and counselling can be provided to parents and

clinical management can be formulated, bearing in

mind the best interests of the child. Initial workup

includes a detailed antenatal and postnatal history,

physical examination, karyotyping, and hormonal

assays. This will guide further workup such as

imaging and genetic analysis. Nonetheless, there are

often limitations to hormonal studies as illustrated

in the present series. The non-distinct pattern of T

and DHT at baseline and following hCG stimulation

in AR mutation–positive and –negative patients

suggest the need to reconsider our laboratory

diagnostic algorithm for AIS.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome is reported

to be the most common cause of 46,XY DSD in a few

ethnic groups,9 10 11 while 5ARD, which is believed to

be rare, was also a major aetiology in our cohort. It

is important to differentiate between 5ARD and AIS

as soon as possible so that patients with 5ARD can

be raised as boys whenever practical.12 The penile

growth of patients with 5ARD can be promoted by

topical DHT treatment and spontaneous virilisation

may occur during puberty. Most of these patients

who are reared as girls during childhood identify

themselves as male and change their gender as

an adult, although we have not received any such

request from our cohort. Exposure to androgen

during the antenatal, postnatal, and pubertal period

may masculinise the brain and influence gender

identity.13 It was found that 5ARD is easy to diagnose

by its characteristic urinary steroid excretion

pattern and its high mutational detection rate in the

SRD5A2 gene.14 Of the 11 patients with 5ARD, eight

harboured the missense mutation p.Arg227Gln in

their SRD5A2 gene, a useful fact to enable screening

for this mutation before proceeding to sequencing

of the whole gene. Unfortunately, patients have

previously been too easily labelled with AIS when

laboratory diagnostic services were less advanced.

This is illustrated by patient 7 who was labelled

as AIS until her urine steroids were analysed and

revealed classic features of 5ARD.15 We recommend

that 5ARD is excluded in all 46,XY DSD patients

before other differential diagnoses are considered.

Moreover, since the baseline and post-hCG–stimulated T and DHT results are unreliable when

diagnosing AIS, genetic study of the AR gene should

also be performed as a first-line investigation.

HSD17B3 deficiency has been reported to be

the most common cause of T biosynthetic defect

leading to 46,XY DSD in some populations, with an

estimated incidence of 1:147 000 in the Netherlands

and as high as 1:200 to 1:300 in Arabians due to their

high consanguinity rate.16 17 Nonetheless, no patient

in our cohort was diagnosed with this condition

based on the hormonal pattern. Ethnic differences

in disease spectrum may be one of the reasons for

this observation. Another possible explanation is

the lack of reliable diagnostic cutoff for the pre- and

post-stimulated T/A4 ratios. George et al18 have

summarised the cutoffs used by various researchers,

with the pre-stimulated cutoff range set at 0.006

to 1.64, and the post-stimulated level set at 0.09 to

3.4 for newborn to teenage groups. The difficulties

in setting up reliable diagnostic cutoffs for the

T/A4 ratio are similar to the T/DHT ratios and have

been discussed in our previous study.14 Furthermore,

HSD17B3 deficiency gives no characteristic findings

on urinary steroid profiling.5 19 Molecular analysis

of the HSD17B3 gene may have offered a means

to diagnose this condition but unfortunately, due

to budget constraints, we were unable to perform

mutational analysis of this gene in all our patients,

although a normal MLPA result in our patients made

gross deletion in this gene unlikely.

The two novel mutations p.Asp266Asn and

p.Thr576Pro in the AR gene lie within the N-terminal

domain of the androgen receptor that is involved

in transcription regulation and DNA binding,

respectively. Missense mutations around these two

codons have been reported in patients with AIS

according to the Androgen Receptor Gene Mutations

Database, April 2013.20 Multiple sequence alignment

shows that both amino acids are highly conserved

among different species, suggesting that aspartic

acid at codon 266 and threonine at codon 576 are

critical for proper receptor function. Similarly, the

alanine at codon 260 of the NR5A1 gene is located in

helix 3 of the ligand-binding domain of the nuclear

receptor,21 and is also a highly conserved region.

Mutation in this region has been reported to result

in 46,XY DSD.8 Replacing alanine at this position

by valine is therefore expected to be deleterious

to the protein function. Phenotypic variability in

NR5A1 gene mutation within a kindred has been

reported and this may explain why patient 21 had

ambiguous external genitalia to such an extent that

he required the attention of a paediatric specialist,

even though his father was fertile, and denied any

symptoms of DSD or need for medical attention.22

For the AMH gene, the 3’ end of exon 5 is one of

the mutational hotspots in patients with PMDS.23

Exon 5 encodes the bioactive C-terminal domain.

The three mutations detected in patient 22 are all

located at highly conserved regions. Although in-vitro

functional characterisation for the mutant

proteins was not performed, the undetectable serum

AMH level in this patient was compatible with

the mutations being pathogenic, possibly due to

abnormal protein folding and increased instability,

as reported previously in mutations located in this

region.24

Gonadal malignancy was rare in our series,

probably because gonadectomy was performed early

in life when the decision of female sex assignment

was made. Although this helps to avoid further

virilisation and to establish gender identity, the

timing of corrective surgery and gonadectomy

remain controversial. Patient advocacy groups have

suggested delaying any surgery for cosmetic reasons

until the patient is mature enough to give informed

consent25 but such practice has not been validated in

our Chinese patients. Whether cultural factors have

any impact on gender assignment remains uncertain

in our community.

Prematurity or low birth weight was not

uncommon in our series. This made diagnosis of

DSD in our patients even more difficult because

ethnic-specific and gestational age– or weight-adjusted anthropometric measurement of the

external genitalia was not available. Assessment of

the genital anatomy relies solely on the experience

of the paediatric specialist and is obviously far from

ideal. A conjoint effort by local paediatricians is

needed to set up these normative data.

Less than half of our patients had a confirmed

diagnosis in the present study. With the increasing

availability of next-generation sequencing technology,

and with its established role in molecular

diagnostic services, including DSD,3 26 it is hoped

that sooner rather than later, most patients will

have a confirmed genetic diagnosis. Nonetheless,

we speculate that some patients have a non-genetic

aetiology since environmental factors may alter the

phenotypic expression. Several animal and human

studies have shown that antenatal exposure to

pesticides and plasticisers may lead to fetal genital

malformation.27

Altogether there was an average of 11 250 male

live births every year in the five public hospitals

that participated in this study. Since 11 newborns

with 46,XY DSD were born in these five hospitals

and were recruited during our study period, this

gives an estimated incidence of 46,XY DSD of

1:2045 male births requiring the input of paediatric

endocrinologists. This figure may underestimate

the true incidence of this group of diseases as some

patients present late and others may have subtle

defects that go unnoticed by our specialists. If the

actual number of patients with chromosomal and

46,XX DSD in our population is considered, the actual

incidence of DSD can be expected to be much higher.

There are a few limitations in this study.

First, the number of patients was relatively small.

This may have resulted in bias in our observation

and the data do not represent the prevalence of

disease in our population. Second, in-vitro study

was not performed on the novel genetic variants for

functional characterisation, although we believe that

all the available evidence indicates the pathogenic

nature of these variants. Third, due to budget

constraints, we were unable to sequence all genes

related to 46,XY DSD.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that 5ARD and AIS are

possibly the major causes of 46,XY DSD in the Hong

Kong Chinese population. Molecular analyses of

the SRD5A2 and AR genes were demonstrated to

be more reliable than hormonal testing. Since the

missense mutation p.Arg227Gln was a recurrent

hotspot mutation in 5ARD in our local patients, all

patients should be screened for this mutation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr YC Ho, Ms YF Wong, and Ms YP Iu for

their technical assistance. The study was supported

by the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Research Grant

2009 QEH/RC/G/0910-A04/R0901 and Kowloon

Central Cluster Research Grant 2012 KCC/RC/G/1213-B01.

References

1. Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Hughes IA; International

Consensus Conference on Intersex organized by the

Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the

European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology. Consensus

statement on management of intersex disorders.

International Consensus Conference on Intersex.

Pediatrics 2006;118.e488-500. Crossref

2. Ono M, Harley VR. Disorders of sex development: new

genes, new concepts. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2013;9:79-91. Crossref

3. Arboleda VA, Lee H, Sánchez FJ, et al. Targeted massively

parallel sequencing provides comprehensive genetic

diagnosis for patients with disorders of sex development.

Clin Genet 2013;83:35-43. Crossref

4. Jääskeläinen J. Molecular biology of androgen insensitivity.

Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012;35:4-12. Crossref

5. Chan AO, Shek CC. Urinary steroid profiling in the

diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia and disorders

of sex development: experience of a urinary steroid referral

centre in Hong Kong. Clin Biochem 2013;46:327-34. Crossref

6. Parajes S, Chan AO, But WM, et al. Delayed diagnosis of

adrenal insufficiency in a patient with severe penoscrotal

hypospadias due to two novel P450 side-chain cleavage

enzyme (CYP11A1) mutations (p.R360W; p.R405X). Eur J

Endocrinol 2012;167:881-5. Crossref

7. Chan WK, To KF, But WM, Lee KW. Frasier syndrome:

a rare cause of delayed puberty. Hong Kong Med J

2006;12:225-7.

8. Allali S, Muller JB, Brauner R, et al. Mutation analysis of

NR5A1 encoding steroidogenic factor 1 in 77 patients

with 46,XY disorders of sex development (DSD) including

hypospadias. PLoS One 2011;6:e24117. Crossref

9. Bangsbøll S, Qvist I, Lebech PE, Lewinsky M. Testicular

feminization syndrome and associated gonadal tumors in

Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1992;71:63-6. Crossref

10. Boehmer AL, Brinkmann O, Brüggenwirth H, et al.

Genotype versus phenotype in families with androgen

insensitivity syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab

2001;86:4151-60. Crossref

11. Abdullah MA, Saeed U, Abass A, et al. Disorders of sex

development among Sudanese children: 5-year experience

of a pediatric endocrinology clinic. J Pediatr Endocrinol

Metab 2012;25:1065-72. Crossref

12. Mieszczak J, Houk CP, Lee PA. Assignment of the sex of

rearing in the neonate with a disorder of sex development.

Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:541-7. Crossref

13. Imperato-McGinley J, Peterson RE, Gautier T, Sturla E.

Androgens and the evolution of male-gender identity

among male pseudohermaphrodites with 5alpha-reductase

deficiency. N Engl J Med 1979;300:1233-7. Crossref

14. Chan AO, But BW, Lee CY, et al. Diagnosis of 5α-reductase

2 deficiency: is measurement of dihydrotestosterone

essential? Clin Chem 2013;59:798-806. Crossref

15. Chan AO, But BW, Lau GT, et al. Diagnosis of 5α-reductase

2 deficiency: a local experience. Hong Kong Med J

2009;15:130-5.

16. Boehmer AL, Brinkmann AO, Sandkuijl LA, et al. 17β-hydroxysteroid

dehydrogenase-3 deficiency: diagnosis,

phenotypic variability, population genetics, and worldwide

distribution of ancient and de novo mutations. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:4713-21. Crossref

17. Rosler A. 17 Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3

deficiency in the Mediterranean population. Pediatr

Endocrinol Rev 2006;3 Suppl 3:455-61.

18. George MM, New MI, Ten S, Sultan C, Bhangoo A. The

clinical and molecular heterogeneity of 17βHSD-3 enzyme

deficiency. Horm Res Paediatr 2010;74:229-40. Crossref

19. Lee YS, Kirk JM, Stanhope RG, et al. Phenotypic variability

in 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-3 deficiency and

diagnostic pitfalls. Clin Endocrinol 2007;67:20-8. Crossref

20. Androgen Receptor Gene Mutations Database. Available from: http://androgendb.mcgill.ca/. Accessed Aug 2013.

21. El-Khairi R, Martinez-Aguayo A, Ferraz-de-Souza B, Lin L,

Achermann JC. Role of DAX-1 (NR0B1) and steroidogenic

factor-1 (NR5A1) in human adrenal function. Endocr Dev

2011;20:38-46.

22. Ciaccio M, Costanzo M, Guercio G, et al. Preserved fertility

in a patient with a 46,XY disorder of sex development

due to a new heterozygous mutation in the NR5A1/SF-1

gene: evidence of 46,XY and 46,XX gonadal dysgenesis

phenotype variability in multiple members of an affected

kindred. Horm Res Paediatr 2012;78:119-26. Crossref

23. Josso N, Belville C, di Clemente N, Picard JY. AMH and

AMH receptor defects in persistent Müllerian duct

syndrome. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:351-6. Crossref

24. Belville C, Van Vlijmen H, Ehrenfels C, et al. Mutations

of the anti-Müllerian hormone gene in patients with

persistent Müllerian duct syndrome: biosynthesis,

secretion, and processing of the abnormal proteins and

analysis using a three-dimensional model. Mol Endocrinol

2004;18:708-21. Crossref

25. Consortium on the Management of Disorders of Sex

Development: Clinical Guidelines for the Management of

Disorders of Sex Development in Childhood. California,

US: Intersex Society of North America; 2006. Available

from: http://www.dsdguidelines.org/files/clinical.pdf.

Accessed Aug 2015.

26. Hersmus R, Stoop H, Turbitt E, et al. SRY mutation

analysis by next generation (deep) sequencing in a cohort

of chromosomal Disorders of Sex Development (DSD)

patients with a mosaic karyotype. BMC Med Genet

2012;13:108. Crossref

27. Kalfa N, Philibert PH, Baskin LS, Sultan C. Hypospadias:

interactions between environment and genetics. Mol Cell

Endocrinol 2011;335:89-95. Crossref